Abstract

The introduction of numerous immunotherapeutic agents into the clinical arena has allowed the long time promise of immunotherapy to begin to become reality. Intralesional immunotherapy has demonstrated activity in multiple tumor types, and as the number of locally applicable agents has increased, so has the opportunity for therapeutic combinations. Both intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (ILBCG) and topical 5% imiquimod cream have been employed as single agents for the treatment of dermal/subcutaneous lymphatic metastases or in-transit melanoma, but the combination has not previously been reported. We used this combination regimen in nine patients during the period from 2004-2011 and report their outcomes here. All patients were initially treated with ILBCG, followed by topical imiquimod after development of an inflammatory response to BCG. In this retrospective study, we examined their demographics, tumor characteristics, clinical and pathologic response to treatment, associated morbidities, local and distant recurrence, and overall survival. The 9 patients (8 male) had a mean age of 72 years (range 56 - 95). Mild, primarily local toxicities were noted. Five patients (56%) had complete regression of their in-transit disease and one had a partial response. The three others had “surgical” complete responses with resection of solitary resistant lesions. The mean interval between the first treatment and complete resolution of in-transit disease was of 6.5 months (range 2 – 12). With a mean follow-up of 35 months (range 12 – 58), seven patients (78%) had not developed recurrent in-transit disease. Two patients (22%) have died of non-melanoma causes, and none have died due to melanoma.

Introduction

In-transit metastasis is a significant clinical challenge in melanoma. This pattern of lymphatic disease spread occurs in approximately 7% of patients and is staged as either Stage IIIB or Stage IIIC, depending on the status of regional nodes.1 It can lead to significant locoregional toxicity, due to painful, bleeding or necrotic lesions which may become superinfected.

Intralesional immunotherapy is a rational approach to such disease since the lesions are accessible and provide a source of ideally matched tumor antigen to facilitate local, and possibly systemic, immune responses. Intralesional administration of microorganisms, bacterial toxins and cytokines has yielded some responses in published reports over a span of more than a century. Refinement of these techniques and the availability of additional immune response modifiers now create the opportunity for combination regimens with increased efficacy. Here we report the clinical outcomes of patients treated with a combination of intralesional Bacille Calmette-Guerin (ILBCG) and the toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) agonist, imiquimod (Aldara, 3M).

Patients and treatment

Nine patients with extensive, broad-based areas of in-transit melanoma metastases were treated by local immunotherapy consisting of ILBCG and imiquimod during the period from 2004 - 2011. Patients were selected for the combination based upon the extent of their disease, making treatment of all areas by ILBCG alone impractical. Patient characteristics are noted in Table 1. All were free of distant metastases at the time of presentation; three of the patients had a history of surgically treated nodal metastases prior to the start of IL-BCG/imiquimod treatment. The goal of this combination immunotherapy was local control and palliation or prevention of symptoms.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Pt | Age | Sex | Site | Time to in-transits(mo) | ILBCG Treatments | Imiquimod Duration (mo) | Follow-up time (mo) | In-transit Disease Response | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | F | scalp | 18 | 4 | 6 | 42.5 | CR | NED |

| 2 | 60 | M | scalp | 20 | 5 | 4 | 55.5 | *sCR | AWD |

| 3 | 95 | M | forearm | 1 | 4 | 11.5 | 49 | *sCR | DOC/NED |

| 4 | 67 | M | scalp | 2 | 3 | 1 | 21 | *sCR | AWD |

| 5 | 73 | M | cheek | 5 | 3 | 4 | 58 | CR | NED |

| 6 | 62 | M | scalp | 5 | 3 | 1.5 | 12 | CR | NED |

| 7 | 74 | M | scalp | 4 | 2 | 2 | 31.5 | CR | AWD |

| 8 | 56 | M | trunk | 15 | 5 | 9 | 28 | CR | NED |

| 9 | 85 | M | scalp | 11 | 4 | 6 | 17 | CR | DOC/NED |

Surgical complete response: Indicates patients who underwent surgical excision of isolated lesions not responding to the combination immunotherapy.

CR: complete response, sCR: surgical complete response, NED: no evidence of disease, AWD: alive with disease, DOC: died of other causes.

Tuberculin delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing was performed to determine initial BCG doses; all patients were negative at the start of treatment. Patients were initially sensitized to BCG at distant sites with intradermal injections of a total of 3 × 106 cfu distributed among eight sites adjacent to undissected regional nodal basins on the first day, and 1.5 × 106 cfu in the same manner two weeks later. Intralesional injection doses following sensitization were generally lower (mean = 1×106 cfu/cc) and were titrated to produce a moderate local inflammatory reaction. To avoid vesiculation and skin necrosis in the center of a widespread cutaneous anti-mycobacterial reaction, each subsequent BCG injection employed decreasing doses of cfu. Lesions were injected no more frequently than every two weeks, as the BCG inflammatory response typically persists for several weeks. Once an inflammatory response was evident in the lesions, 5% topical imiquimod was applied five to seven days/week and titrated to a moderate level of local inflammation. Frequency of application was decreased or temporarily interrupted to avoid any severe local toxicities. Intralesional and topical therapy was continued until complete resolution of disease or progression. Isolated, solitary resistant lesions were resected. In five cases biopsies were taken of areas with residual pigment to evaluate for persistent disease. ILBCG was administered an average of four times (range 2 – 5) (Table 1). Topical imiquimod was used for a mean duration of five months (range 1 – 11.5) with intermittent periods of treatment rest.

Results

Overall the combination immunotherapy was very well tolerated. Common side effects were mild injection pain (Grade 1), injection site reaction (moderate erythema, induration and ulceration (Grade 1-2)), and mild fevers and chills (Grade 1). (Figures 1-3) Inflammatory responses to imiquimod induced similar local toxicity. No treatment-related Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred, and there were no cases of systemic BCG infection.

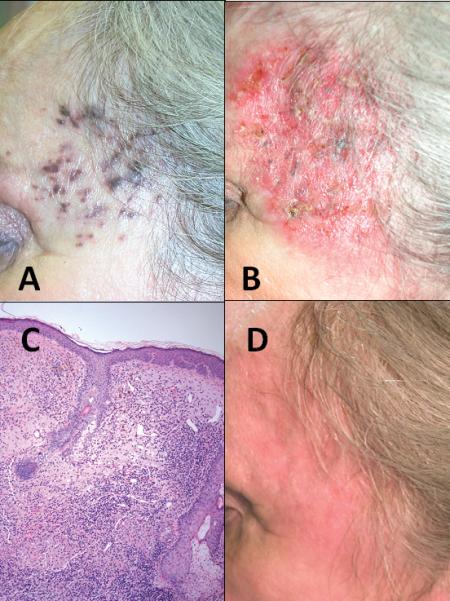

Figure 1.

Patient 1 is a 72 year old female who developed recurrent in-transit melanoma lesions on her scalp (Figure 1A) after failure of multiple wide excisions and radiation therapy. She received four treatments of ILBCG which resulted in decreased pigmentation and subsequent ulceration of the injected lesions (Figure 1B). Imiquimod was prescribed for a total of six months and resulted in a brisk inflammatory response. Biopsy of a persistent area of pigmentation revealed a dense mononuclear reaction with small granulomas and no residual melanoma (Figure 1C). The patient's response was complete ten months from the start of the ILBCG/Imiquimod therapy (Figure 1D). She remains without evidence of disease after 42.5 months.

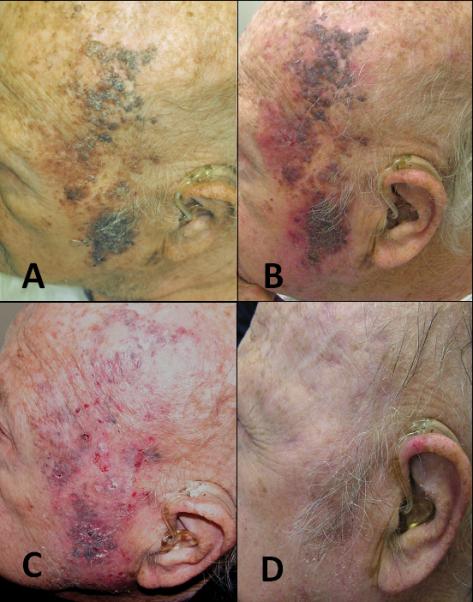

Figure 3.

Patient 9, an 85 year old male with a history of peripheral vascular disease and end-stage renal failure, presented with in-transit disease involving his scalp and face (figure 3A). After undergoing four treatments of ILBCG, areas of ulceration and inflammatory reaction were evident (figure 3B.) He received a total of six months of imiquimod therapy resulting in a brisk inflammatory response (figure 3C). By nine months after the start of his combination therapy his response was complete (figure 3D).

Complete regression of all evident disease occurred in 5 (56%) patients. Three (33%) of patients underwent resection of solitary resistant lesions. These resections were performed during the course of regression of other sites of disease and all three patients went on to complete resolution of evident melanoma. The average length of treatment until complete resolution of all in-transit lesions was 6.5 months (range 2 – 12). Average follow-up time for this cohort was 35 months (range 12 – 58). At last follow-up 6 (67%) patients remained without evidence of disease. One (11%) patient developed additional in-transit lesions after 7.5 months and is now undergoing additional local immunotherapy with combination IL-BCG and imiquimod. A second (11%) patient recurred with in-transit disease after a period of 34 months and then 8 months later with distant disease. A third (11%) patient developed pulmonary metastases after a period or 12.5 months. Two patients have died of non-melanoma causes at 17 and 55.5 months; none have died of melanoma.

Biopsies were performed on five patients during their treatment course. In two cases, areas of residual pigment demonstrated hemosiderin-laden macrophages, dermal fibrosis, and chronic inflammation without evidence of residual melanoma (Figure 1C). In three cases, clinically resistant solitary lesions were excised demonstrating exuberant granulomatous and chronic inflammation and focal necrosis (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Patient 3 is a 95 year old male with extensive, bulky in-transit melanoma involving his forearm (Figure 2A). Multiple ILBCG injections were performed on 4 occasions with injection into larger, more nodular areas of disease. Imiquimod was continued for 11.5 months (figure 2B). During his treatment, a solitary 2cm nodule that was not responding to therapy was excised, and pathologic evaluation revealed a dense lymphohistiocytic inflammatory response within the melanoma (Figure 2C). Thirteen months after the start of his combination immunotherapy, this patient had no evidence of disease (figure 2D). He subsequently died of pneumonia after 49 months at the age of 99 with no evidence of melanoma.

Discussion

These patients’ presentations demonstrate that in-transit melanoma can be extensive and disfiguring and is the potential source of significant morbidity. Currently the mainstays of therapy include surgical excision, isolated limb perfusion/infusion with chemotherapy, or systemic therapy. Recently electrochemotherapy has become more commonly used in European centers, and some other intralesional therapies, such as Rose Bengal (PV-10), have been under evaluation. 2 Resection is often appropriate for single, or small numbers of lesions. However, with simple excision, recurrences at new in-transit sites are the rule. Response to isolated, regional chemotherapy such as isolated limb perfusion (ILP) or isolated limb infusion (ILI) can yield high response rates (ILP: 88-100%, ILI: 44-100%), some of which are durable. 3 However, the procedure is only possible in the limb and entails the risk of substantial regional toxicity, including the risk of edema, erythema, skin loss and compartment syndrome acutely, and fibrosis or lymphedema over the long term. Systemic therapies, although they are experiencing dramatic recent improvements, are ineffective in the majority of metastatic melanoma patients. 4, 5

Intralesional immunotherapy was initially reported by William Coley in the late 1800s. 6 Coley injected surgically incurable tumors with a mixture of bacterial toxins derived from cultures of erysipelas and bacillus prodigiosus. However, the substantial toxicity of this regimen, and inconsistent responses prevented widespread acceptance of the therapy. In the modern era, intralesional immunotherapy was described by Morton and colleagues in the 1970s using ILBCG. 7 Regression of injected lesions in up to 90% of patients and regression of non-injected lesions in up to 17% were reported. However, substantial toxicities occurred when high doses where given to previously sensitized patients. These included disseminated intravascular coagulation, anaphylaxis and death and caused the treatment to fall from widespread use. At a small number of centers, ILBCG has continued to be used and the treatment has evolved to use much lower doses than those that were associated with severe toxicity. The relatively benign nature of this treatment was evident in our current case series.

The combination regimen reported here utilizes the mature dosing of ILBCG in combination with a relatively new immunomodulator, the TLR7 agonist, imiquimod. It is an approved therapy for superficial basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratoses and genital warts. It has been reported in small series as a single agent in treating in-transit metastases, though follow up data are still quite limited and subcutaneous failures may occur. 8,9 One advantage of the cream is the ability to treat a relatively broad surface area and diffuse lesions, which can be difficult with intralesional injections alone.

Application of topical imiquimod is known to cause local release of cytokines such and interferon-α and activation of local inflammatory and antigen-presenting cells. In melanoma patients, application of imiquimod at the primary tumor site has been shown to increase lymphocyte infiltration of the skin and draining lymph nodes. 10 More strikingly, pre-clinical studies employing the combination of imiquimod with a Listeria monocytogenes-based vaccine dramatically increased both local and systemic anti-melanoma immunity. In these preclinical studies, both the Listeria vaccine and imiquimod individually offered partial control of local tumors and lung metastases, but the combination led to “profound and highly reproducible tumor rejection.” 11 The multiple pattern recognition receptor agonists present in BCG and imiquimod may provide sufficient adjuvant to stimulate an immune response against autologous tumor antigens.

As the outcomes for this small series of stage III patients are surprisingly favorable,further clinical and laboratory evaluation is warranted to determine whether this combination induces systemic anti-melanoma immunity, . Regional control with this regimen was excellent, and with selective surgical resection, 78% achieved complete and durable locoregional control. Furthermore at the time of this report (with a median of 30 months of follow up), no patient in this series has died of melanoma.

Footnotes

All authors have declared there are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Johnson MM, et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:587–96. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testori A, Faries MB, Thompson JF, et al. Local and intralesional therapy of in-transit melanoma metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:391–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.22029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Testori A, Verhoef C, Kroon HM, et al. Treatment of melanoma metastases in a limb by isolated limb perfusion and isolated limb infusion. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:397–404. doi: 10.1002/jso.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nauts HC, Swift WE, Coley BL. The treatment of malignant tumors by bacterial toxins as developed by the late William B. Coley, M.D., reviewed in the light of modern research. Cancer Res. 1946;6:205–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morton D, Eilber F, Holmes E, et al. BCG immunotherapy of malignant melanoma: summary of a seven-year experience. Ann Surg. 1974;180:635–43. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197410000-00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bong A, Bonnekoh B, Franke I, et al. Imiquimod, a topical immune response modifier, in the treatment of cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma. Dermatology. 2002;205:135–8. doi: 10.1159/000063904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turza K, Dengel LT, Harris RC, et al. Effectiveness of imiquimod limited to dermal melanoma metastases, with simultaneous resistance of subcutaneous metastasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:94–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayan R, Nguyen H, Bentow JJ, et al. Immunomodulation by imiquimod in patients with high-risk primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:163–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craft N, Bruhn KW, Nguyen BD, et al. The TLR7 agonist imiquimod enhances the anti-melanoma effects of a recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccine. J Immunol. 2005;175:1983–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]