Abstract

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a homodimer that binds to two distinct receptor types, TrkA and p75, to support survival and differentiation of neurons. The high-affinity binding on the cell surface is believed to involve a heteroreceptor complex, but its exact nature is unclear. We developed a heterodimer (heteromutein) of two NGF muteins that can bind p75 and TrkA on opposite sides of the heterodimer, but not two TrkA receptors. Previously described muteins are Δ9/13 that is TrkA negative and 7-84-103 that is signal selective through TrkA. The heteromutein (Htm1) was used to study the heteroreceptor complex formation and function, in the putative absence of NGF-induced TrkA dimerization. Cellular binding assays indicated that Htm1 does not bind TrkA as efficiently as wild-type (wt) NGF but has better affinity than either homodimeric mutein. Htm1, 7-84-103, and Δ9/13 were each able to compete for cold-temperature, cold-chase stable binding on PC12 cells, indicating that binding to p75 was required for a portion of this high-affinity binding. Survival, neurite outgrowth, and MAPK signaling in PC12 cells also showed a reduced response for Htm1, compared with wtNGF, but was better than the parent muteins in the order wtNGF > Htm1 > 7-84-103 >> Δ9/13. Htm1 and 7-84-103 demonstrated similar levels of survival on cells expressing only TrkA. In the longstanding debate on the NGF receptor binding mechanism, our data support the ligand passing of NGF from p75 to TrkA involving a transient heteroreceptor complex of p75-NGF-TrkA.

Keywords: TrkA-p75 heteroreceptor complex, high-affinity binding, ligand passing model

Nerve growth factor (NGF), the founding member of the neurotrophin family, promotes development of the vertebrate nervous system and maintenance of discrete populations of neurons (McDonald and Chao, 1995; Bibel and Barde, 2000; Kaplan and Miller, 2000; McAllister, 2001) via selective binding to the TrkA receptor (Bibel and Barde, 2000; Neet and Campenot, 2001). NGF also binds to a second receptor, the common neurotrophin receptor p75 (Bibel and Barde, 2000; Neet and Campenot, 2001). Functionally, NGF exists as a noncovalently bound dimer (26.5 kDa) consisting of two identical protomers (13 kDa) interacting with each other through hydrophobic interactions (McDonald et al., 1991; McDonald and Chao, 1995). The NGF dimer has two identical faces formed at the edges of the interface to which the receptors bind with amino acids from both protomers (McDonald and Chao, 1995; Wiesmann et al., 1999; He and Garcia, 2004; Wehrman et al., 2007).

The TrkA receptor is a 140-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein with an intracellular domain (ICD) with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, triggered by transautophosphorylation by ligand-induced receptor dimerization, leading to differentiation and survival (Kaplan et al., 1991; Loeb et al., 1994; Vambutas et al., 1995; Cunningham et al., 1997; Bibel and Barde, 2000). The N-terminus of NGF interacts with the d5 subdomain of TrkA-extracellular domain (ECD). Other binding regions of NGF to TrkA include a continuous binding surface of residues in exposed loops (Ibanez et al., 1991, 1993; Ilag et al., 1994). The p75 receptor, containing a cysteine-rich ECD and an ICD death domain, is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family (Gruss, 1996). NGF has two highly conserved binding regions for p75 that interact with all four subdomains of p75-ECD (Ibanez et al., 1992; Ryden and Ibanez, 1997). Although mostly mediating an apoptotic response (Maria Frade et al., 1996; Yoon et al., 1998; Casaccia-Bonnefil et al., 1999; Lievremont et al., 1999; Miller and Kaplan, 2001), the p75 receptor can induce survival, especially in the presence of TrkA (Carter et al., 1996; Maliartchouk and Saragovi, 1997).

Extensive binding studies have identified two binding sites, termed the high-affinity binding (~10 pM) and the low-affinity binding (~1 nM; Sutter et al., 1979; Landreth and Shooter, 1980; Bernd and Greene, 1984; Woodruff and Neet, 1986) sites. The p75 receptor displayed low-affinity binding (Radeke et al., 1987; Rodriguez-Tebar et al., 1991). In one study, the TrkA receptor demonstrated high-affinity binding along with lowaffinity binding by itself (Jing et al., 1992). However, key studies have demonstrated that the high-affinity binding and responsiveness were observed only when both receptors were coexpressed (Hempstead et al., 1990, 1991; Mahadeo et al., 1994; Barker and Shooter, 1994; Ryden et al., 1997; Esposito et al., 2001). The high-affinity, slow-dissociating binding is now believed to have contributions from both TrkA and p75 (Mahadeo et al., 1994; Barker, 2007). However, an exact mechanism or model for generating this high-affinity binding is still actively debated (He and Garcia, 2004; Barker, 2007; Wehrman et al., 2007).

In the present study, we use a novel heterodimer consisting of two NGF muteins (a heteromutein) that can form a TrkA-p75 heteroreceptor complex but is unable to dimerize TrkA and thus is unable to form the high-affinity binding site made of TrkA dimers. Our binding data support a ligand-passing model with a transient heteroreceptor complex. The complexities of the signaling data suggest that interactions exist between NGF and TrkA in addition to the loops and subdomains defined in crystal structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Mouse Δ9/13 NGF and 7-84-103 NGF cDNA were cloned in pBluebac 4.5 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and expressed in Sf21 insect cells as described elsewhere (Woo et al., 1995; Mahapatra et al., 2009). Polyclonal antibodies (pAb) for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were obtained from EMD (Bedford, MA), Cedarlane Labs (Burlington, NC), Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), Millipore (Bedford, MA), Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA), and KPL Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD).

Cell Culture

Rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12, TrkA+/p75+) and mouse fibroblast cells (MG139, rat TrkA+/p75–; Barker et al., 1993) were obtained from Lloyd A. Green and Phillip Barker and cultured as previously described (Mahapatra et al., 2009). Briefly, the cell lines were propagated in 15% serum media (Dulbeco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM, with 4.5 mg/ml glucose and sodium pyruvate, without L-glutamine] supplemented to contain 10% heat-inactivated horse serum [HS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY], 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [FBS; Gibco], 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 U penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B) and incubated at 37°C with 6.5% CO2. Sf21 (Spodoptera frugiperda) insect cells were cultured and propagated in T75 flasks in 10% serum media (complete TNM-FH; Grace's insect cell media [Gibco], supplemented to contain 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [FBS; Gemini Biosciences, West Sacramento, CA]) incubated at 27°C, as described by Woo et al. (1995).

Protein Expression and Purification

Proteins were expressed in Sf21 insect cells using the Bac-N-Blue system (Invitrogen) as previously described (Woo et al., 1995; Mahapatra et al., 2009). Sf21 cells were infected with baculovirus containing the gene of interest at a multiplicity of infection of 1–10 and harvested on the fourth day. NGF and muteins were purified from cell supernatant using a two-step protocol yielding >95% pure protein. The first step of the purification was successive cation exchange chromatography with HiPrep 16/10 SP FF (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) and two 16/10 CM FF (carboxymethyl fast flow; GE Life Sciences) columns in series. The proteins were eluted off the column using 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl (pH 9.0) at 0.1–0.5 ml/min. The second step of purification was immunoaffinity with anti-NGF mouse monoclonal antibody N60 (Neet et al., 1987) coupled to Sepharose beads in a 2-ml column (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 9.0) The protein was eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.3) and transferred to storage buffer (0.4% acetic acid).

Formation and Purification of the Heterodimer

Purified Δ9/13 and 7-84-103 muteins were mixed together in 0.4% acetic acid (pH 3–4) and incubated at 4°C for a minimum of 24 hr for the formation of heterodimers. The mixture was then dialyzed into 0.01 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The dialyzed protein mixture was used for heterodimer purification with a 0.2-ml weak cation exchange HPIEC column, polyCAT A (Nest Group, Southborough, MA; Burton et al., 1992). The column was equilibrated in buffer A (0.01 M potassium phosphate, 5% ethanol, pH 6.0), and the elution was performed using a step gradient procedure with increasing buffer B (0.01 M potassium phosphate, 0.8 M potassium chloride, 5% ethanol, pH 6.0). Native nonequilibrium isoelectric focusing (IEF) gels (Moore and Shooter, 1975) were used to demonstrate formation and separation of the heterodimer from parent homodimers.

Neurite Outgrowth Bioassay

PC12 cells were used for the differentiation (neurite outgrowth) assay in defined medium as previously described (Reinhold and Neet, 1989; Mahapatra et al., 2009). After 48 hr, cells displaying processes longer than 1.5 times the cell body were scored as neurite-bearing cells; at least 200 total cells were counted per well in triplicate.

Cell Survival Assays

Exponentially growing PC12 cells were incubated, with or without NGF or mutein, for 72 hr at 37°C in serum-free DMEM (10,000 cells/well) and assayed for viability by addition of 0.4% trypan blue solution (Mahapatra et al., 2009). After 30–60 sec of incubation, the trypan blue solution was removed and the cells were visualized under a phase-contrast microscope; at least 200 cells were counted per well in triplicate. Alternatively, exponentially growing MG139 cells were incubated, with or without NGF or mutein, for 72 hr at 37°C in serum-free DMEM (5,000 cells/well) and assayed for viability by addition of XTT to each well (Mahapatra et al., 2009). The formation of the orange-colored formazan dye, indicating viable cells, was spectrophotometrically measured at 450 nm in triplicate using a multiwell plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Labeling of NGF, Radiolabeled Ligand Receptor Competition Binding Assays, and Cold Chase Dissociation

Highly purified wild-type (wt) NGF obtained from mouse submaxillary glands was used for 125I labeling as previously described (Woodruff and Neet, 1982; Woo et al., 1995). Two separate iodinations were carried out with specific activities of 87 cpm/pg and 37 cpm/pg. The radiolabeled NGF preparations were not used beyond 3 weeks, and the TCA precipitability determined then was at least 93%.

Competition binding was measured as previously described (Woodruff and Neet, 1982; Woo et al., 1995). In brief, a single concentration of 125I-NGF was used in competition with increasing concentrations of either wtNGF, 7-84-103, Htm1, or Δ9/13. Two different cell lines that either express both receptors (PC12 cell line) or express only the TrkA receptor (MG139 cell line) were used in log-phase growth. Washed PC12 cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated in Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) assay buffer, containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and D-glucose, for 30 min with 0.1 nM of 125I-NGF in the presence or absence of competitor. For MG139 cells, a final cell concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml and 0.2 nM of 125I-NGF were incubated for 45 min. After incubation, bound 125I-NGF was separated from free 125I in 100-μl aliquots on 0.3 M sucrose cushions. A 1,000-fold excess (100 nM) of unlabeled NGF was used in parallel to determine the amount of nonspecific binding.

Cold-temperature cold-chase dissociation kinetics of 125I-labeled NGF were assayed by incubation with PC12 cells at room temperature for 45 min, followed by 5 min of incubation on ice as previously described (Woodruff and Neet, 1982; Woo et al., 1995). The dissociation of bound 125I-NGF was initiated by addition of 1,000-fold excess of unlabeled NGF at 0.5°C, and the bound was separated from the free by centrifugation. Nonspecific binding was determined by adding 1,000-fold excess unlabeled NGF during the 45-min incubation. Competing ligands were added to the 125I-NGF for the 45-min incubation phase, followed by 5 min of incubation on ice, and then cold temperature cold chase was initiated by addition of 1,000-fold excess unlabeled NGF and incubation for 30 min at 0.5°C.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

PC12 cells were grown in 15% serum media at 37°C, 6.5% CO2 on 100-mm poly-l-ornithine-coated plates. PC12 cells in the log phase were serum starved for 24 hr before treatment and then incubated with wtNGF or the mutein for 5 min at 37°C, 6.5% CO2 and then lysed. Preparation of cell lysates; immunoprecipitation (PC31 antibody; EMD); immunoblotting of TrkA; and immunoblotting of the lysates for phosphorylated forms of MAPK, Akt, PLCγ, SAPK/JNK, p38, and MEK1/2 have previously been described (Lad and Neet, 2003; Lad et al., 2003; Mahapatra et al., 2009).

RESULTS

Heteromutein 1 Is Formed From the Two Muteins and Is Stable in Mixtures

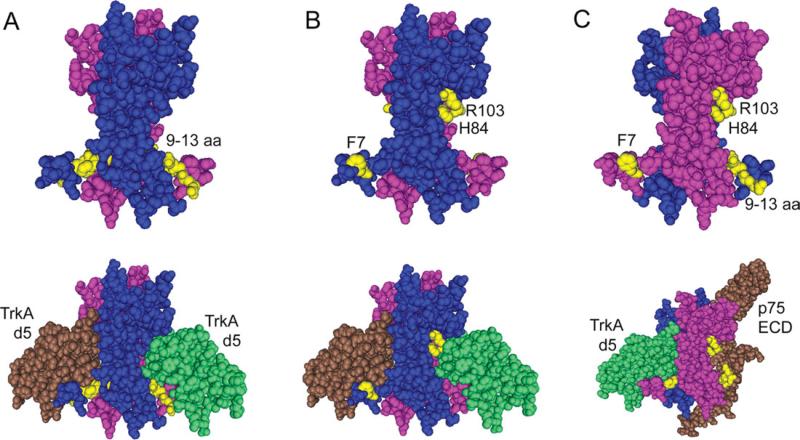

To study the TrkA-p75 heteroreceptor complex, we formed a heterodimer of two NGF muteins that can bind TrkA on only one side but still can bind p75 to form a heteroreceptor complex (Fig. 1), using two NGF muteins that have reduced binding to TrkA, Δ9/13 and 7-84-103 (Woo et al., 1995; Mahapatra et al., 2009). The Δ9/13 NGF mutein, a deletion mutant, with N-terminal residues 9–13 deleted (Fig. 1A), demonstrates no TrkA binding or activity (Woo et al., 1995; Hughes et al., 2001). The 7-84-103 NGF mutein, mutated at residues F7, H84, and R103 to alanine (termed 7-84-103; Fig. 1B), has 200-fold reduced binding to TrkA and is signal selective for survival over neuritogenesis (Mahapatra et al., 2009). The two muteins form a heteromutein, which can bind TrkA on only one side at the NGF protomer–protomer interface. The 9–13 amino acid residues and the H84 and R103 lie on opposite sides of the NGF protomer (Fig. 1C). Thus, in the heterodimer, the H84 and R103 come from one protomer, whereas the 9–13 amino acids are from the second protomer on each side of the NGF interface that can bind TrkA (Fig. 1). The heteromutein design allows the study of signaling and binding of a monovalent NGF heterodimer binding on only one side to a single TrkA protomer. This heteromutein Htm1 has the ability to bind normally to p75 and thus the capability to bind the putative heteroreceptor complex (Fig. 1C), in the absence of TrkA homodimerization.

Fig. 1.

Design rationale for an NGF heteromutein capable of forming a TrkA-NGF-p75 complex but not a TrkA-NGF-TrkA complex. A: The 9–13 amino acids on the N-terminus of NGF are highlighted in yellow on each protomer (pink, blue) of NGF dimer (upper structure). These amino acids are deleted in the mutein Δ9/13 that is unable to bind TrkA. The lower structure shows the interaction of residues 9–13 with TrkA d5 domain (brown, green). B: The F7, H84, and R103 amino acids are highlighted in the NGF dimer (upper structure), and their interaction with TrkA d5 domains (brown, green) is shown in the lower structure. F7A/H84A/R103A (7-84-103) mutein is an NGF mutein binding weakly to TrkA. C: A dimer of NGF in which 9–13 amino acids are highlighted on one protomer (pink) and F7, H84, and R103 are highlighted on the other protomer (blue) of NGF shows that, if these highlighted residues are mutated or deleted, it would abolish TrkA binding on one side (upper structure). Therefore, a heterodimer of Δ9/13 mutein and the 7-84-103 mutein would lose TrkA binding on one side but still have the ability to form a heteroreceptor complex (p75 ECD, brown; TrkA d5, green; lower structure). PDB IDs for NGFTrkA(d5) complex and NGF-p75 complex are 1WWW and 1SG1, respectively.

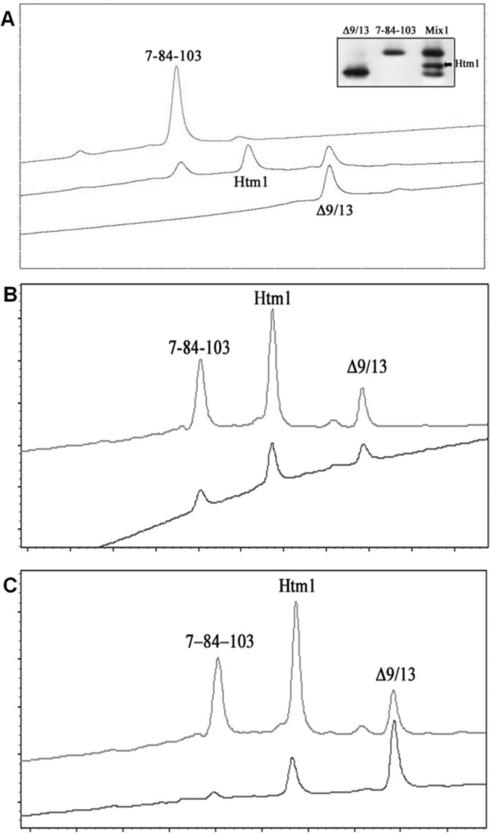

We used a low-pH protocol, 0.4% acetic acid storage buffer (Moore and Shooter, 1975; Radziejewski and Robinson, 1993), for the formation of the heterodimer (Htm1). A 1:1 mixture of 7-84-103 and Δ9/13 was incubated at pH of about 3–4 for 1 day, and the formation of Htm1 was detected by two different methods that utilize the difference in the theoretical pI values of the parent muteins, 7-84-103 and Δ9/13, 8.58 and 9.11, respectively, and Htm1. Isoelectric focusing (IEF) gels and high-performance ion-exchange chromatography (HPIEC) have been used for separation of mutant NGF species that differ by a single charged amino acid (Moore and Shooter, 1975; Burton et al., 1992) and show three separate bands or peaks for the mixture (Fig. 2A). The first and the third bands/peaks represent 7-84-103 and Δ9/13, respectively, as confirmed by running the individual muteins on the IEF (Fig. 2A, inset) and the HPIEC (Fig. 2A). Thus, the central band/peak represents Htm1.

Fig. 2.

Separation, purification, and stability of Htm1. The parent muteins 7-84-103 and Δ9/13 were mixed 1:1 in 0.4% acetic acid (traditional storage buffer) and incubated at 4°C for at least 24 hr to form Htm1. Separation was achieved using HPIEC on a weak cation exchange column (polyCAT A), using a step gradient protocol. A: Separation profile for Htm1 from the parent muteins (middle trace). The upper trace is for 7-84-103 alone, and the bottom trace is for Δ9/13 alone. Inset: Separation pattern on an IEF gel; lane 1: Δ9/13; lane 2: 7-84-103; lane 3: Htm1 (Mix1a). B: Eluted Htm1 (from the central peak, upper trace), separated from the parent muteins in the Mix1a, was dialyzed out of the elution buffer for 8 hr and reloaded on the column (lower trace). Shorter times of stability could not be tested because a 4-hr dialysis did not sufficiently remove the salts to allow proper chromatography. C: Two different mixtures of the parent muteins were analyzed for the ratio of the three species of NGF muteins at equilibrium. Mix1a: 1:1 mixture of 7-84-103 and Δ9/13 was mixed and incubated for at least 24 hr at 4°C (upper trace). Mix1: 1:2 mixture of 7-84-103 and Δ9/13 was mixed and incubated for 24 hr at 4°C (lower trace).

The HPIEC method was used to study the stability of Htm1. The purified Htm1 was dialyzed in the cold for 8 hr to remove excess salt. A shorter time of dialysis did not remove the salts adequately. The stability of the heterodimer was determined after the dialysis. The results (n = 2) show reformation of Htm1 into a 1:2:1 (25%:51%:24%) mixture of 7-84-103:Htm1:Δ9/13 (Fig. 2B). The two muteins had been chosen for the formation of the heterodimer to circumvent a possible problem that could arise from either an inability to purify the heterodimer or the more detrimental reformation of original homodimers. The Δ9/13 mutein is nonfunctional with respect to TrkA, and 7-84-103 is 100-fold higher in EC50 for neuritogenesis, which could be an interfering or contributing component in the mixture (Woo et al., 1995; Mahapatra et al., 2009). Because the purified Htm1 was not completely stable, another mixture was obtained by mixing 7-84-103 and Δ9/13 in a 1:2 ratio compared with 1:1. This mixture (Mix1) has less than 5% 7-84-103 compared with 34% in the other mixture (Mix1a), determined using the area under the peak (Fig. 2C). The amount of Htm1 was relatively similar, 40% in Mix1a and 37.5% in Mix1. The amount of Δ9/13 was much higher in Mix1 than Mix1a, 60% vs. 26%. Because Δ9/13 is a TrkA nonfunctional mutein, even an excess of this homodimeric mutein should not be a contributing factor in the bioassay of the mixture. The percentage of Htm1 was calculated from the area under the peaks of the traces (Fig. 2C) to estimate the concentration of Htm1 for each experiment.

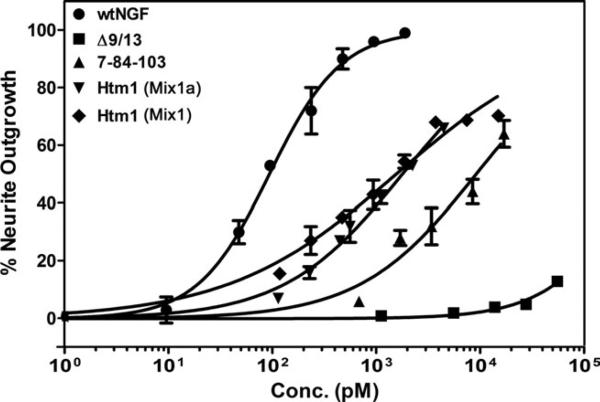

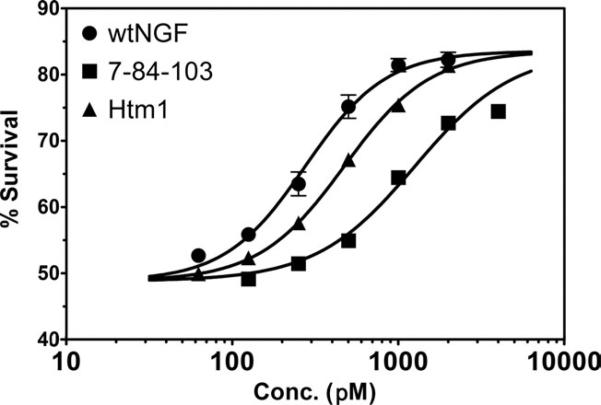

Htm1 Has an EC50 Intermediate Between Wild-Type NGF and Each Mutein in the Neurite Outgrowth Bioassay

PC12 cells (TrkA+/p75+) were used to test for the ability of the parent muteins and Htm1 to induce neu-rites (Fig. 3). As expected, Δ9/13 does not induce neurites because it has been shown not to bind TrkA (Woo et al., 1995; and see figures below). The EC50 for NGF is, as expected, ~0.1 nM, and that for 7-84-103 is ~10 nM (Mahapatra et al., 2009). Hence, 7-84-103 is active compared with Δ9/13 but ~100-fold less potent than wtNGF. The percentage of Htm1 in each mixture, Mix1 and Mix1a, was calculated from the area under the peaks of the traces in Figure 2C and used to estimate the concentration of Htm1 in each mixture. The data for the response of the two mixtures were then plotted for the amount of Htm1 in each mixture. Both mixtures show a very similar dose response for the calculated Htm1 concentration (Fig. 3) and very similar EC50 values (1.8 nM and 1.6 nM). In Mix1, the amount of 7-84-103 is very low (<5%; Fig. 2C), so the response is almost certainly due to Htm1. Thus, the functional similarity of two mixtures with different ratios of the parent muteins and Htm1 indicates that a single component is responsible for the observed response. This result verifies the sufficient stability of the Htm1 equilibrium mixture to use Htm1 in subsequent studies. The Htm1 is, thus, better than either parent mutein in the generation of neurites, but not as good as wtNGF (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. PC12 cells were used to measure the number of neurite-bearing cells after treatment with neurotrophins. Different concentrations of wtNGF, Δ9/13, 7-84-103, Htm1 (Mix1a), and Htm1 (Mix1) were added to PC12 cells in defined medium to stimulate neurite outgrowth for 48 hr. In this and subsequent figures, the concentration of Htm1 in each mixture was calculated from the total protein concentration and the percentage of Htm1 area under the peaks of the corresponding trace in Figure 2C and then plotted as the concentration of Htm1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM with n = 3. The dose–response curves were fit to the data points in GraphPad Prism 5.02. Data for wtNGF and 7-84-103 are from Mahapatra et al. (2009).

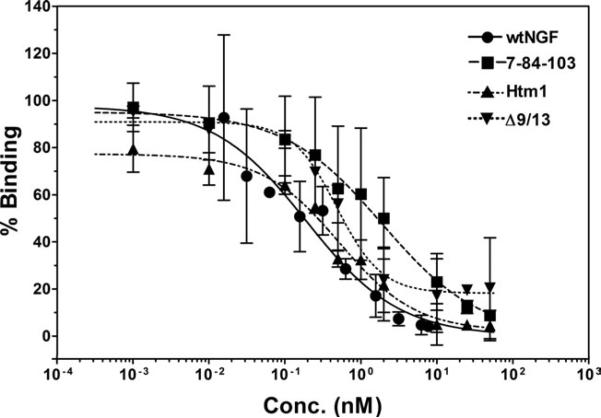

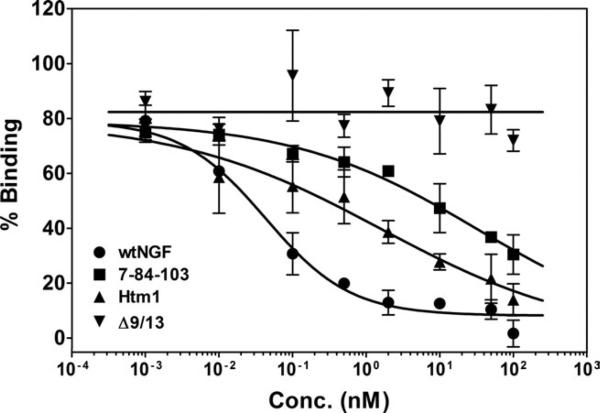

Htm1 Bound With Affinity Similar to That of wtNGF to PC12 Cells

The ability of Htm1 and the muteins to bind to both classes of receptors was determined using PC12 cells. Increasing concentrations of the muteins and wtNGF in competition with 125I-NGF were used to generate competitive binding curves (Fig. 4). The binding for all the muteins, as indicated by their IC50 values (Table I), was similar to wtNGF, probably because of their similar ability to bind p75 on PC12 cells (present at 10-fold higher amount than TrkA). The high IC50 for 7-84-103 was not significantly different from wtNGF and the other muteins because of the high error for this mutein (Table I). Thus, Htm1 bound similarly to wtNGF and 7-84-103 to PC12 cells that express both receptors.

Fig. 4.

PC12 cell (TrkA+/p75+) competitive binding assay. Increasing concentrations of muteins were used in competition with labeled wtNGF to generate competition binding curves in cells expressing both p75 and TrkA receptors. PC12 cells were incubated in the presence of 0.1 nM 125I-NGF in the presence or absence of competing ligands for 30 min at room temperature, followed by determination of the bound fraction in 100-μl aliquots. Bound 125I-NGF in the absence of a competing ligand was set at 100% binding to determine relative binding. The data are presented as mean ± range, n = 2. Competitive binding curves were fit to the data points in GraphPad Prism. The IC50s determined from these individual binding curves (wtNGF = 0.22 nM, 7-84-103 = 1.9 nM, Htm1 = 0.53 nM, Δ9/13 = 0.51 nM) are similar to those listed for averages in Table I.

TABLE I.

Summary of Functional and Binding Characteristics of NGF Muteins and Heteromuteins

| wtNGF | 7-84-103 | D9/13 | Htm1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurite outgrowth using PC12 cellsa | ||||

| EC50 (nM) | 0.1 | 10 | ndb | 1.8 |

| Fold differencec | 1 | 100 | nd | 18 |

| XTT assay for survival using M139 cellsd | ||||

| EC50 (nM) | 0.76 | 17 | ND | 19 |

| Fold difference | 1 | 22 | nd | 25 |

| Trypan blue survival assay using PC12 cellse | ||||

| EC50 (nM) | 0.28 | 1.26 | nd | 0.47 |

| Fold difference | 1 | 4.5 | nd | 1.7 |

| Competition binding using MG139 cellsf | ||||

| IC50 (nM) | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 11.5 ± 9 | ND | 0.67 ± 0.8 |

| Fold difference | 1 | 386 | nd | 22 |

| Competition binding using PC12 cellsg | ||||

| IC50 (nM) | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 2.45 ± 2.8 | 0.46 ± 0.5 | 0.59 ± 0.04 |

Determined from dose–response curves in Figure 3.

ND, not detected; nd, not determined.

The fold differences are relative to wtNGF. The fold difference in an EC50 or IC50 should be inversely proportional to the relative binding affinity of the molecule to the receptor(s).

Determined from dose–response curves in Figure 7.

Determined from dose–response curves in Figure 8.

Determined from cellular binding (Fig. 5, n = 2) from curve fitting two independent replicate experiments. MG139 cells contain TrkA receptor only.

Determined from cellular binding (Fig. 4; n = 2) from curve fitting two independent replicate experiments. PC12 cells contain both TrkA and p75 receptors. The fold difference was not calculated for this set of data because the large error, particularly with the 7-84-103, makes it misleading.

Htm1 Bound MG139 Cells With Lower Affinity Than wtNGF but With Higher Affinity Than Both 7-84-103 and Δ9/13

MG139 cells (TrkA+/p75–) are transfected fibroblasts that express low levels of TrkA, similar to PC12 cells, and were used to examine the relative affinities of the muteins to full-length TrkA in a cellular context. The 7-84-103 mutein showed a markedly reduced affinity for TrkA (~386-fold) when using wtNGF for comparison (Fig. 5). Htm1 also showed reduced affinity (~22-fold) for TrkA compared with wtNGF, but Htm1 affinity was better than that of 7-84-103. As expected, Δ9/13 did not show any binding to TrkA in MG139 cells (Table I). Thus, Htm1 binding to full-length TrkA in MG139 cells was intermediate between the binding of wtNGF and 7-84-103. The hierarchy (wtNGF > Htm1 > 7-84-103) found here in MG139 binding data parallel the results from the neurite outgrowth (Table I).

Fig. 5.

MG139 cell (TrkA+/p75–) competitive binding assay. Increasing concentrations of muteins and wtNGF were used to compete with labeled wtNGF to generate competition binding curves in cells expressing TrkA only. MG139 cells were incubated with 0.2 nM 125I-NGF in the presence or absence of competing ligands for 45 min at room temperature, followed by determination of the bound fraction in 100-ll aliquots. Bound 125I-NGF in the absence of a competitor was set at 100% binding to determine relative binding. The data are presented as mean ± range, n = 2. Competitive binding curves were fit to the data points in GraphPad Prism. The IC50s determined from these binding curves (wtNGF = 0.04 nM, 7-84-103 = 15 nM, Htm1 = 0.64 nM, Δ9/13 = no binding) are similar to those listed for averages in Table I.

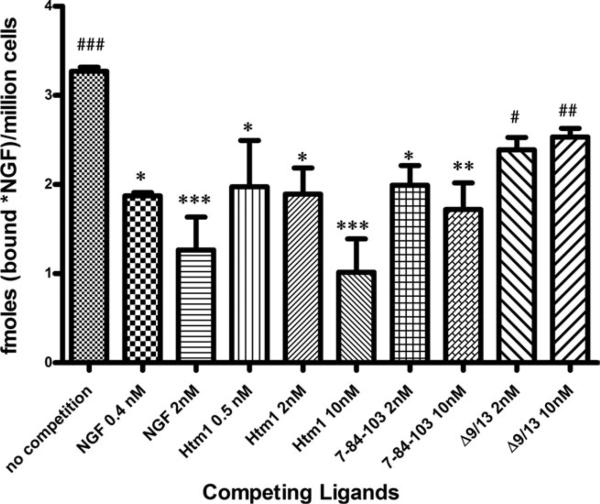

Htm1 Bound the High-Affinity Binding Site Better Than 7-84-103 and Δ9/13

Competition for cold-chase stable binding at 0.5°C in PC12 cells (TrkA+/p75+) was used to assess Htm1 binding to the high-affinity site on cells expressing both receptors. The cold-temperature, cold-chase protocol (see Materials and Methods) allows for stabilization of the high-affinity site, because dissociation from the high-affinity site at cold temperatures is extremely slow (Landreth and Shooter, 1980; Woodruff and Neet, 1986; Weskamp and Reichardt, 1991; Woo et al., 1995). This condition reflects the fast dissociation from p75 receptors and the slow dissociation from TrkA components. The dissociation in the absence of competition is biphasic, with a fast dissociating component (t1/2 ~ 0.6 min) and a very slow dissociating component (Woodruff and Neet, 1986). The dissociation for the slow binding component is stable at 30 min (data not shown), and this time was used to evaluate the high-affinity binding remaining when a competitor is present during binding. When 0.4 nM cold wtNGF is added as a competing ligand during the 30-min incubation, most of the fast dissociating component is competed away and the slow component is reduced by about half, but the rates of dissociation do not change. At 2 nM for 30 min of incubation, wtNGF, 7-84-103, and Htm1 showed a statistically significant (P < 0.05) reduction in high-affinity binding (Fig. 6). Higher concentrations of wtNGF (2 nM) and Htm1 (10 nM) were further able to reduce the cold stable binding, which was statistically significant in comparison with 10 nM Δ9/13. However, the same was not observed with 10 nM 7-84-103. Thus, the ability of Htm1 to reduce cold stable binding is better than that of either parent mutein.

Fig. 6.

Cold-temperature, cold-chase stable competition binding. Wild-type NGF (0.2 nM 125I-NGF) was incubated with PC12 cells (106 cells/ml) in the absence or presence of a competitor for 45 min at room temperature, followed by 5 min of incubation on ice (0.5°C). A 1,000-fold excess of cold wtNGF was added to initiate dissociation of bound 125I-NGF and allowed to incubate on ice for an additional 30 min. The bound fraction was separated from free and represents the amount of cold-chase stable specific binding remaining after competition with the muteins. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3, and statistical significance was computed by using Dunnett's multiple-comparisons test as a posttest following a significant one-way ANOVA test (P = 0.0012). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 represent significant difference in the amount of cold cold-chase stable binding remaining after competition in comparison with no competition. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 represent significant difference in the amount of cold cold-chase stable binding remaining compared with 10 nM Htm1.

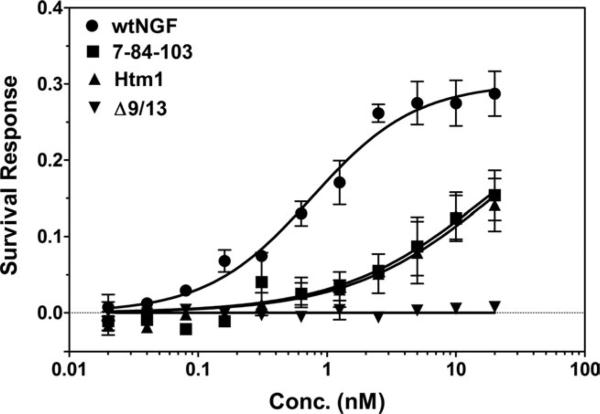

Htm1 Induces a Survival Response Similar to That of 7-84-103 in Cells Expressing Only TrkA

We also used MG139 cells (p75–/TrkA+) to determine the mitogenic response of the muteins through TrkA alone (as measured by the XTT assay). Because the Δ9/13 mutein showed no binding (Fig. 5), it did not induce a survival response in MG139 cells (Fig. 7). The EC50s for 7-84-103 (17 nM) and Htm1 (19 nM) were similar but significantly higher than the EC50 obtained for wtNGF (760 pM; Fig. 7, Table I), demonstrating the importance of the cellular milieu for mutein-TrkA interaction.

Fig. 7.

XTT assay of cell survival response in MG139 cells (TrkA+/p75–). Increasing concentrations of wtNGF or its muteins were added to log-phase MG139 cells in 96-well plates for 72 hr at 37°C. The XTT reagent was added for another 4 hr, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured on a multiwell plate reader (Tecan). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for three separate experiments.

Htm1 Displays Increased Survival Signaling Through TrkA in the Presence of p75

To determine the effect of p75 on the TrkA survival response, we used PC12 cells (p75+/TrkA+) and the trypan blue assay to generate dose–response survival curves for wtNGF, 7-84-103, and Htm1 (Fig. 8). With the XTT assay, two metabolically active processes (survival and differentiation) can occur simultaneously, and, even though there may be wild-type levels of survival, the lack of induction of differentiation (neurite outgrowth) will yield a lower XTT response. As observed with neurite outgrowth assay, Htm1 displayed a better survival response than 7-84-103 but reduced survival compared with wtNGF. The EC50 values determined from the curves (Table I) show that Htm1 has about twofold higher EC50 (0.47 nM) than wtNGF (0.28 nM), and 7-84-103 displayed an EC50 (1.26 nM) about 4.5-fold higher than Htm1. Thus, in presence of p75, Htm1 displays better bioactivity than 7-84-103.

Fig. 8.

Trypan blue assay of cell survival response in PC12 cells (TrkA+/p75+). Increasing concentrations of either wtNGF or its muteins were added to log-phase PC12 cells, and cell survival was determined after 72 hr by counting cells under a phase-contrast microscope. The data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. Dose–response curves were generated in GraphPad Prism.

Cellular Phosphorylation and Function

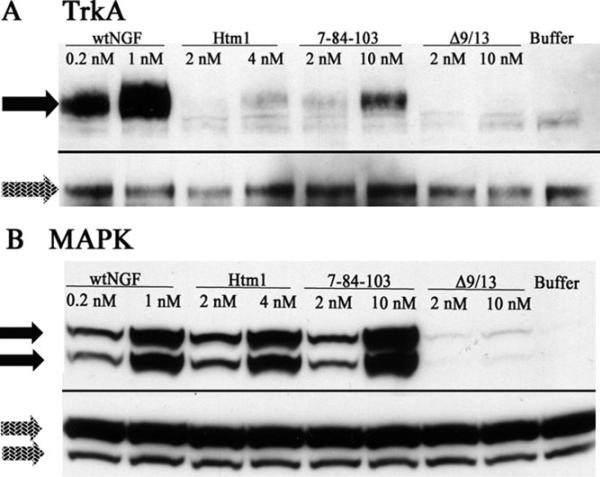

Because the binding and bioassay assays suggested that Htm1 binds well and strongly signals for survival and neurite outgrowth, we next examined the phosphorylation levels of important signaling molecules. Two concentrations of ligand were tested with PC12 cells (p75+/TrkA+) at 5 min (Lad and Neet, 2003; Lad et al., 2003) by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (TrkA) or immunoblotting of lysates (MAPK, Akt, PLCg, MEK1/2, p38, SAPK/JNK) with their antiphosphoantibodies. The NGF concentration of 1 nM was chosen to obtain maximal activation of the signaling cascade, whereas 0.2 nM NGF was chosen because it gave ~50% of the neurite outgrowth response. The concentrations of 10 nM for 7-84-103 and 4 nM for Htm1 were chosen because they were functionally comparable to 0.2 nM wtNGF in relation to neurite outgrowth. The lower concentrations for the two ligands were used because they gave 50% response compared with the higher concentrations. MEK1/2 and p38 revealed no phosphorylation, SAPK/JNK was constitutively activated across all treatments, and PLCγ gave barely detectable levels of phosphorylation (data not shown). TrkA and MAPK showed significantly different levels of phosphorylation for different treatments (Fig. 9). Akt was similar to TrkA (data not shown). TrkA and MAPK phosphorylation levels were quantified and compared with each other (Table II). MAPK phosphorylation was significantly higher than with buffer alone for all treatments (P < 0.05) except for 2 nM 7-84-103 and all Δ9/13 concentrations. Unlike MAPK, TrkA phosphorylation was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than buffer only for wtNGF or 10 nM 7-84-103. Significant differences (P < 0.001) between MAPK and TrkA phosphorylation were observed for the higher concentrations of 7-84-103 (10 nM) and Htm1 (4 nM) only, indicating loss of the correlation between TrkA activation and MAPK activation observed with wtNGF. Overall, the level of TrkA activation was very weak for Htm1 compared with the higher levels for wtNGF and the 10 nM concentration of 7-84-103.

Fig. 9.

TrkA and MAPK phosphorylation in PC12 cells. A: TrkA phosphorylation was determined by immunoprecipitating TrkA, followed by immunoblotting with a pan-phosphotyrosine antibody. Once phosphoprotein bands (black arrows) were identified and scanned, the blot was stripped and reprobed with an anti-TrkA antibody to determine total TrkA (gray arrows). B: Phospho-MAPK was detected by running the lysate on the gel, followed by immunoblotting using a phospho-MAPK antibody (black arrows). The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-MAPK antibody to detect total MAPK (gray arrows). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used for band detection by chemiluminescence.

TABLE II.

Semiquantitative Analysis of TrkA and MAPK Phosphorylation†

| TrkA phosphorylation (%) |

MAPK phosphorylation (%) |

Neurites (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| wtNGF (1 nM) | 100 | — | 100 | — | 96 |

| wtNGF (0.2 nM) | 50.15★ | 11.92 | 61.99## | 8.9 | 69 |

| Htm1 (2 nM) | 35.4 | 11.5 | 49.33## | 10.31 | 55 |

| Htm1 (4 nM) | 30.67 | 6.27 | 77.79###,‡‡‡ | 11.52 | 62 |

| 7–84–103 (2 nM) | 27.37 | 9.5 | 36.93# | 9.19 | 25 |

| 7–84–103 (10 nM) | 50.57★ | 3.63 | 88.73###,‡‡‡ | 11.59 | 50 |

| Δ9/13 (2 nM) | 21.6 | 3.06 | 14.84 | 1.67 | 2 |

| Δ9/13 (10 nM) | 17.39 | 5.93 | 14.06 | 1.03 | 7 |

| Buffer | 17.83 | 1.64 | 12.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

Immunoblots for TrkA and MAPK were used to make semiquantitative determinations of the degree of TrkA and MAPK activation for each treatment. Ratios of phosphoprotein band intensity to total protein band intensity are represented as percentages and are relative to 1 nM wtNGF (set at 100%). The data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 separate cell treatments. Statistically significant differences were computed by using one-way and two-way ANOVAs, followed by posttests for differences between assays of the same treatment and between the different treatments for the same assay using Bonferroni's and Dunnett's multiple-comparisons posttests, respectively. Neurite outgrowth values for the concentrations tested were determined from the neurite outgrowth curves (Fig. 3) to provide a comparative perspective between cell signaling and function. The number of symbols represents the level of significance. A single symbol represents P < 0.05, two symbols represent P < 0.01, and three replicate symbols represent P < 0.001.

Statistically significant differences in percentage TrkA phosphorylation for individual treatments compared with buffer.

Statistically significant differences in percentage MAPK phosphorylation for individual treatments compared with buffer.

‡Statistically significant differences between percentage MAPK phosphorylation and percentage TrkA phosphorylation for the same treatment.

DISCUSSION

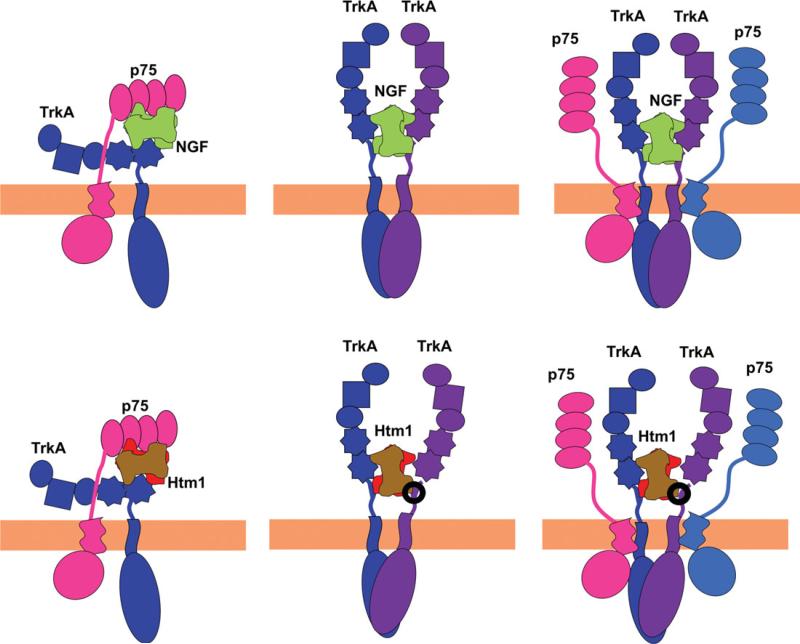

NGF Receptor Binding Models and the Heteromutein Approach

Mechanistically, the high-affinity binding is believed to involve increased sensitivity mediated by TrkA. Although there is agreement on the involvement of p75 in forming the high-affinity site, its exact role has been debated for 2 decades. Two major models have been proposed. 1) The TrkA presentation model proposes preformed complexes of TrkA and p75, which can act as the high-affinity binding site (Esposito et al., 2001). Because the p75-ECD was not required for high-affinity binding in that study, p75 was proposed to bind TrkA through other domains and to modify TrkA such that it has a higher affinity for NGF (Esposito et al., 2001). Furthermore, identification of pre-existing TrkA-p75 chimeric complexes indicates that the p75 receptor binds to the TrkA receptor through its ICD and transmembrane regions converting TrkA into a high-affinity binding site for NGF (Wolf et al., 1995; Ross et al., 1996). 2) The ligand-passing model proposes that the fast on rate of p75 “concentrates” NGF at the membrane surface (Barker and Shooter, 1994; Barker, 2007). The increased local concentration allows binding to TrkA, which has a slower on rate. The NGF is thus believed to be passed from a fast off receptor (p75) to a slow on receptor (TrkA). In this view, the high-affinity binding is a process, rather than an actual site. NGF can be recruited at the surface by binding to a single p75 receptor (He and Garcia, 2004) or two p75 receptors (Gong et al., 2008). During the transfer of ligand from p75 to TrkA, a transient heteroreceptor complex may be formed, consisting of an NGF dimer bound on one side by p75 and on the other by TrkA (Wehrman et al., 2007). This heteroreceptor complex could represent the high-affinity site, either as the transient intermediate in the ligand-passing model or as a stable independent receptor complex that binds with higher affinity than the individual receptors. These two complexes are depicted in Figure 10. Htm1 was specifically developed to be able to test the formation of the second complex by designing the formation of a more stable p75-NGF-TrkA complex. The design of this heterodimer allows study of the TrkA-NGF-p75 complex in the absence of TrkA dimerization. The homodimeric muteins, themselves, have a greatly reduced activity toward TrkA. The utilization of an equilibrium mixture for Htm1 was validated by the correspondence of activity curves (Fig. 3)

Fig. 10.

Model of ligand passing and TrkA presentation for NGF binding. Upper row: NGF. Lower row: Htm1. Left column: Putative complex of NGF or Htm1 with TrkA and p75 that represents an intermediate in the ligand-passing model. Note the antiparallel orientation of the two receptors resulting from the binding mode of each ligand relative to the membrane (Barker, 2007). The formation of this complex would be preceded by the binding of NGF or Htm1 to the p75 receptor. Middle column: NGF or Htm1 binding to a homodimeric TrkA receptor. The binding pathway for NGF or Htm1 to form this complex can occur by directly binding to TrkA or via the two-step ligand-passing process, which involves formation of the complex shown in the left column. Right column: Putative heteroreceptor complex of undefined stoichiometry in the Trk presentation model. This complex represents the TrkA presentation model. A pre-existing TrkA-p75 heteroreceptor complex can bind to NGF with greater affinity than TrkA alone. In the lower middle and lower right models, the area in the circle designates additional modes of interaction among Htm1 loop L-I, L-II, and L-IV residues and the extracellular, juxtamembrane region of TrkA to explain the cellular and signaling data (see Discussion).

Comparison of Binding

With TrkA in MG139 cells (TrkA+/p75–), 7-84-103 had a 386-fold lower binding than wtNGF compared with only a 22-fold reduction for Htm1. The low binding of TrkA for 7-84-103 is due to the mutations in the conserved patch, which directly contacts the TrkA d5 subdomain. The reduced affinity of the Htm1 with respect to wtNGF suggests that the Htm1 does not bind to TrkA as a result of inability of one side to bind TrkA, but the higher affinity than a homodimeric mutein (7-84-103 and Δ9/13) reflects the ability of the other side to bind as wtNGF would bind TrkA. The PC12 competition binding studies indicate relatively similar affinities for wtNGF, both muteins, and Htm1. PC12 cells express about tenfold more p75 receptors than TrkA receptors (Woodruff and Neet, 1986). Because the muteins and Htm1 are not mutated to lose p75 binding, they can compete for p75 with 125I-NGF. At the concentration of 0.1 nM 125I-NGF, the ratio of low-affinity to high-affinity binding by NGF is about 1. The inability of Δ9/13 to bind TrkA is reflected in its inability to compete fully with bound 125I-NGF and flattening of the competition binding curve at about 20%. This lack of complete displacement can be due to 125I-NGF either bound to a TrkA homodimer or bound to a heteroreceptor complex of undefined stoichiometry with additional p75 molecules. Either alternative requires the ability to bind TrkA that Δ9/13 lacks.

The high-affinity binding, as measured by competition for cold-chase stability (Landreth and Shooter, 1980; Woodruff and Neet, 1986), demonstrated that Htm1 bound better than either parent mutein (Fig. 6). In either the ligand-passing model or the TrkA presentation model, binding to TrkA will ultimately affect the cold-chase stable binding. Thus, these data support the notion that Htm1 is better able to compete with 125I-NGF for the cold stable binding than 7-84-103 because Htm1 binds better to TrkA (Table I). Both Δ9/13 and 7-84-103 muteins show reduction in the cold-chase stable binding when added as competitors to binding of wtNGF. Because Δ9/13 does not bind TrkA, the component of slow-dissociating binding with which Δ9/13 competes may involve a complex containing p75. This result supports the ligand-passing model, i.e., the involvement of p75 in generating the high-affinity site. The ability of Htm1 to inhibit the cold-chase stable binding better than the parent muteins arises both from its ability to bind TrkA with greater affinity (Fig. 5) and from its undiminished ability to bind p75. This interpretation should be taken with the caveat that Htm1 was presented in an equilibrium mixture; however, because of the binding properties of the Δ9/13 and 7-84-103 parents, low levels of these homodimers would not be expected to have much influence on this result.

Differentiation and Survival Responses to Htm1

The binding data correlate well with the neurite outgrowth data using PC12 (TrkA+/p75+) cells (18- vs. 100-fold) but correspond less well to the survival assay performed with MG139 cells (25- vs. 22-fold). Although 7-84-103 was selected to promote survival (Mahapatra et al., 2009) and had reduced binding to TrkA, Htm1 was as good or better at inducing survival in either cell line. Htm1 would not be expected to give a strong survival response with MG139 cells (TrkA+/p75–) via TrkA transautophosphorylation, because it is monovalent for TrkA and should bind to only a single TrkA protomer without promoting receptor homodimerization. However, two recent studies using monomeric, low-molecular-weight ligands have suggested that monomers of TrkB (Cazorla et al., 2010) or TrkA (Brahimi et al., 2010) can transphosphorylate chains without forming a true tyrosine kinase receptor homodimer. This same ability may be in play here with Htm1.

Because Htm1 provided a better neurite outgrowth response than 7-84-103, PC12 cells (TrkA+/p75+) were also used to study the survival response compared with MG139 cells (TrkA+/p75–). Unlike the case with MG139 cells, the survival response for Htm1 was improved compared with 7-84-103 (1.7- vs. 4.5-fold), suggesting that the presence of p75 facilitates binding of the Htm1 to TrkA (ligand-passing model) and an efficient survival response. We postulate that Htm1 was better able to pass on from p75 to TrkA, thus providing a possible explanation for increased activity of Htm1 in presence of p75, in support of the ligand-passing model (see Fig. 10).

Signal Transduction Pathways Activated Via Other NGF Loops and TrkA Domains

We found that Htm1 gave a strong MAPK signal and a moderate neurite response but only a weak TrkA signal compared with 7-84-103, which gave a strong MAPK signal and a similar TrkA signal but poor neurite outgrowth (Table II). Only wtNGF shows a close relationship among all three parameters. Thus, the efficiency of converting the MAPK signal into neurite outgrowth response occurs in the rank order wtNGF > Htm1 > 7-84-103 (Fig. 9). As part of its signal-selective properties (Mahapatra et al., 2009), 7-84-103 does not have wtNGF's ability to translate the MAPK phosphorylation into neurite outgrowth, but Htm1 is able to induce MAPK phosphorylation and neurite outgrowth through relatively low levels of TrkA phosphorylation (Table II). Htm1 and 7-84-103 may be unable to form the active state of the receptor complex efficiently. Binding of NGF to the high-affinity site (Barker and Shooter, 1994) or to p75 (Saragovi et al., 1998; Colquhoun et al., 2004) when disrupted by a specific antibody, downstream signaling including gene expression, is markedly reduced. A reduced efficiency of MAPK signaling may thus be explained by a possible alteration in the TrkA ICD conformation, which eventually affects differentiation and gene expression (Mahapatra et al., 2009).

Other studies have shown evidence for additional subdomains of the TrkA-ECD and other residues of NGF contributing to complex formation and/or activation. Heterodimers between different neurotrophins have been demonstrated to be functional but not as good as the individual wt homodimers, and a possible explanation for signaling for heterodimers via Trk receptors has been suggested (Treanor et al., 1995). Studies with NGF muteins have identified residues in loops L-I, L-II, and L-IV (Wiesmann et al., 1999; also defined as variable regions I, II, and V [Ibanez et al., 1991, 1993; Ilag et al., 1994]) that form a continuous surface and are apparently important for activation of TrkA (Ibanez et al., 1991, 1993; Ilag et al., 1994). In the TrkA-NGF structure, these loop residues do not contact the d5 domain and are presented toward the membrane side (Wehrman et al., 2007). Thus, these residues may have a functional role by influencing activation via interaction with the extracellular juxtamembrane region of full-length TrkA. The mutations on one side of Htm1 do not allow for binding to TrkA, but the other side can bind TrkA with good affinity. Thus, after binding one TrkA, if another TrkA is close enough, activation of the TrkA receptors may occur through the amino acids in loops LI, L-II, and L-IV, as depicted in Figure 10. Thus, our Htm1 data support other significant interactions between NGF loop residues and TrkA-ECD subdomains that influence signaling.

CONCLUSIONS

The heteromutein Htm1 was used to test the ligand-passing model or any model requiring a heteroreceptor complex of p75-NGF-TrkA. Neither simple high-affinity agonist nor simple antagonist activity was observed with Htm1. Therefore, the binding data do not directly support the heteroreceptor complex as the high-affinity binding site, which would indicate a heteroreceptor complex of p75-NGF-TrkA. The cold-chase stable competition observed with Δ9/13, however, demonstrates that not all but some (~27%; Fig. 6) of the cold-chase stable binding requires binding of NGF to p75 and thus supports the ligand-passing model that would involve the formation of the p75-NGF-TrkA complex as an intermediate. Additionally, Htm1 showed better neurite outgrowth and survival than 7-84-103 in a cell line (PC12) that coexpressess both receptors but very similar survival in a cell line (MG139) with similar expression levels of TrkA but without p75. The expression levels of TrkA in PC12 and MG139 are relatively similar, suggesting that p75 is critical for improved NGF responsiveness. Coupled with the observations for Δ9/13 cold-chase stable binding and improved Htm1 function over 7-84-103 in the presence of p75, the data provide evidence for ligand interaction with p75 in increased NGF responsiveness and binding, thus supporting the ligand-passing model.

The ligand-passing model, though, is inadequate to explain how Htm1 would signal via TrkA (MG139 cells), because Htm1 cannot bind a second TrkA and thus directly dimerize TrkA. The MG139 binding data and the PC12 cell signaling data, such as better MAPK signaling efficiency for Htm1 than for 7-84-103, may require additional interactions of NGF with neighboring TrkA molecules for receptor activation or, perhaps, after internalization and crowding on endosomes (Barker et al., 2002). These considerations are summarized in the model shown in Figure 10. Our data do not entirely rule out the TrkA presentation model, but our data and the existing literature do not rule out the ligand-passing model either. It is possible for both models to coexist, which would agree with our data. Similarly to our findings, Weskamp and Reichardt (1991) reported two classes of high-affinity receptors, one that required p75 and the other that was indenpendent of p75. Future studies with heteromuteins with loop mutations in combination with chimeric receptors may identify the involvement of other domains of TrkA and regions of NGF in binding and activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this work were submitted to Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree (H.M.M.). We thank Promila Pagadala and Sid Mahapatra for helpful discussions of these experiments. We gratefully appreciate the critical reading of the manuscript by Drs. Philip Barker and H. Uri Saragovi, McGill University, and Drs. Joeseph Dimario and Marc J. Glucksman, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; Contract grant number: NS24380.

Footnotes

Hrishikesh M. Mehta's current address is Department of Pediatrics (Hematology–Oncology), Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL

REFERENCES

- Barker PA. High affinity not in the vicinity? Neuron. 2007;53:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PA, Shooter EM. Disruption of NGF binding to the low affinity neurotrophin receptor p75LNTR reduces NGF binding to TrkA on PC12 cells. Neuron. 1994;13:203–215. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PA, Lomen-Hoerth C, Gensch EM, Meakin SO, Glass DJ, Shooter EM. Tissue-specific alternative splicing generates two isoforms of the trkA receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15150–15157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PA, Hussain NK, McPherson PS. Retrograde signaling by the neurotrophins follows a well-worn trk. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:379–381. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernd P, Greene LA. Association of 125I-nerve growth factor with PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. Evidence for internalization via high-affinity receptors only and for long-term regulation by nerve growth factor of both high- and low-affinity receptors. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:15509–15516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Barde Y-A. Neurotrophins: key regulators of cell fate and cell shape in the vertebrate nervous system. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2919–2937. doi: 10.1101/gad.841400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi F, Liu J, Malakhov A, Chowdhury S, Purisima EO, Ivanisevic L, Caron A, Burgess K, Saragovi HU. A monovalent agonist of TrkA tyrosine kinase receptors can be converted into a bivalent antagonist. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LE, Schmelzer CH, Szonyi E, Yedinak C, Gorrell A. Activity and biospecificity of proteolyzed forms and dimeric combinations of recombinant human and murine nerve growth factor. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1937–1945. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BD, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B, Offenhauser N, Bohm-Matthaei R, Baeuerle PA, Barde Y-A. Selective activation of NF-kappa B by nerve growth factor through the neurotrophin receptor p75. Science. 1996;272:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Chenghua G, Khursigara G, Chao MV. p75 Neurotrophin receptor as a modulator of survival and death decisions. Microsc Res Techniq. 1999;45:217–224. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990515/01)45:4/5<217::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, Jouvenceau A, Rose C, Guilloux J-P, Pilon C, Dranovsky A, Premont J. Cyclotraxin-B, the first highly potent and selective TrkB inhibitor, has anxiolytic properties in mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun A, Lawrance GM, Shamovsky IL, Riopelle RJ, Ross GM. Differential activity of the nerve growth factor (NGF) antagonist PD90780 [7-(benzolylamino)-4,9-dihydro-4-methyl-9-oxo-pyrazolo[5,1-b]quinazoline-2-carboxylic acid] suggests altered NGF-p75NTR interactions in the presence of TrkA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:505–511. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ME, Stephens RM, Kaplan DR, Greene LA. Auto-phosphorylation of activation loop tyrosines regulates signaling by the TRK nerve growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10957–10967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D, Patel P, Stephens RM, Perez P, Chao MV, Kaplan DR, Hempstead BL. The cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of the p75 and Trk A receptors regulate high affinity binding to nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32687–32695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Cao P, Yu H-j, Jiang T. Crystal structure of the neurotrophin-3 and p75NTR symmetrical complex. Nature. 2008;454:789–793. doi: 10.1038/nature07089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss HJ. Molecular, structural, and biological characteristics of the tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1996;26:143–159. doi: 10.1007/BF02592977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Garcia KC. Structure of nerve growth factor complexed with the shared neurotrophin receptor p75. Science. 2004;304:870–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1095190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead BL, Patil N, Thiel B, Chao MV. Deletion of cytoplasmic sequences of the nerve growth factor receptor leads to loss of high affinity ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9595–9598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead BL, Martin-Zanca D, Kaplan DR, Parada LF, Chao MV. High-affinity NGF binding requires coexpression of the trk proto-oncogene and the low-affinity NGF receptor. Nature. 1991;350:678–683. doi: 10.1038/350678a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Messineo-Jones D, Lad SP, Neet KE. Distinction between differentiation, cell cycle, and apoptosis signals in PC12 cells by the nerve growth factor mutant delta9/13, which is selective for the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:10–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010101)63:1<10::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez CF, Ebendal T, Persson H. Chimeric molecules with multiple neurotrophic activities reveal structural elements determining the specificities of NGF and BDNF. EMBO J. 1991;10:2105–2110. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez CF, Ebendal T, Barbany G, Murray-Rust J, Blundell TL, Persson H. Disruption of the low affinity receptor-binding site in NGF allows neuronal survival and differentiation by binding to the trk gene product. Cell. 1992;69:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez CF, Ilag LL, Murray-Rust J, Persson H. An extended surface of binding to Trk tyrosine kinase receptors in NGF and BDNF allows the engineering of a multifunctional pan-neurotrophin. EMBO J. 1993;12:2281–2293. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilag LL, Lonnerberg P, Persson H, Ibanez CF. Role of variable beta-hairpin loop in determining biological specificities in neurotrophin family. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19941–19946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing S, Tapley P, Barbacid M. Nerve growth factor mediates signal transduction through trk homodimer receptors. Neuron. 1992;9:1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90066-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DR, Martin-Zanca D, Parada LF. Tyrosine phosphorylation and tyrosine kinase activity of the trk proto-oncogene product induced by NGF. Nature. 1991;350:158–160. doi: 10.1038/350158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lad SP, Neet KE. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway through p75NTR: a common mechanism for the neurotrophin family. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:614–626. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lad SP, Peterson DA, Bradshaw RA, Neet KE. Individual and combined effects of TrkA and p75NTR nerve growth factor receptors: a role for the high affinity receptor site. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24808–24817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreth GE, Shooter EM. Nerve growth factor receptors on PC12 cells: ligand-induced conversion from low- to high-affinity states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:4751–4755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievremont JP, Sciorati C, Morandi E, Paolucci C, Bunone G, Della Valle G, Meldolesi J, Clementi E. The p75NTR-induced apoptotic program develops through a ceramide-caspase pathway negatively regulated by nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15466–15472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb DM, Stephens RM, Copeland T, Kaplan DR, Greene LA. A Trk nerve growth factor (NGF) receptor point mutation affecting interaction with phospholipase C-gamma 1 abolishes NGF-promoted peripherin induction but not neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8901–8910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeo D, Kaplan L, Chao MV, Hempstead BL. High affinity nerve growth factor binding displays a faster rate of association than p140trk binding. Implications for multi-subunit polypeptide receptors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6884–6891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra S, Mehta H, Woo SB, Neet KE. Identification of critical residues within the conserved and specificity patches of nerve growth factor leading to survival or differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33600–33613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliartchouk S, Saragovi HU. Optimal nerve growth factor trophic signals mediated by synergy of TrkA and p75 receptor-specific ligands. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6031–6037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06031.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria Frade J, Rodriguez-Tebar A, Barde Y-A. Induction of cell death by endogenous nerve growth factor through its p75 receptor. Nature. 1996;383:166–168. doi: 10.1038/383166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister AK. Neurotrophins and neuronal differentiation in the central nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1054–1060. doi: 10.1007/PL00000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald NQ, Chao MV. Structural determinants of neurotrophin action. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19669–19672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald NQ, Lapatto R, Murray-Rust J, Gunning J, Wlodawer A, Blundell TL. New protein fold revealed by a 2.3-A resolution crystal structure of nerve growth factor. Nature. 1991;354:411–414. doi: 10.1038/354411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FD, Kaplan DR. Neurotrophin signalling pathways regulating neuronal apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/PL00000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JB, Jr, Shooter EM. The use of hybrid molecules in a study of the equilibrium between nerve growth factor monomers and dimers. Neurobiology. 1975;5:369–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neet KE, Campenot RB. Receptor binding, internalization, and retrograde transport of neurotrophic factors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1021–1035. doi: 10.1007/PL00000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neet KE, Fanger MW, Baribault TJ, Barnes D, David AS. Derivation of monoclonal antibody to nerve growth factor. Methods Enzymol. 1987;147:186–194. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)47109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radeke MJ, Misko TP, Hsu C, Herzenberg LA, Shooter EM. Gene transfer and molecular cloning of the rat nerve growth factor receptor. Nature. 1987;325:593–597. doi: 10.1038/325593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziejewski C, Robinson RC. Heterodimers of the neurotrophic factors: formation, isolation, and differential stability. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13350–13356. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold DS, Neet KE. The lack of a role for protein kinase C in neurite extension and in the induction of ornithine decarboxylase by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3538–3544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Tebar A, Dechant G, Barde Y-A. Neurotrophins: structural relatedness and receptor interactions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;331:255–258. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AH, Daou MC, McKinnon CA, Condon PJ, Lachyankar MB, Stephens RM, Kaplan DR, Wolf DE. The neurotrophin receptor, gp75, forms a complex with the receptor tyrosine kinase TrkA. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:945–953. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryden M, Ibanez CF. A second determinant of binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor revealed by alanine-scanning mutagenesis of a conserved loop in nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33085–33091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryden M, Hempstead B, Ibanez CF. Differential modulation of neuron survival during development by nerve growth factor binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16322–16328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragovi HU, Zheng W, Maliartchouk S, DiGugliemo GM, Mawal YR, Kamen A, Woo SB, Cuello AC, Debeir T, Neet KE. A TrkA-selective, fast internalizing nerve growth factor–antibody complex induces trophic but not neuritogenic signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34933–34940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter A, Riopelle RJ, Harris-Warrick RM, Shooter EM. Nerve growth factor receptors. Characterization of two distinct classes of binding sites on chick embryo sensory ganglia cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:5972–5982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treanor JJS, Schmelzer C, Knusel B, Winslow JW, Shelton DL, Hefti F, Nikolics K, Burton LE. Heterodimeric neurotrophins induce phosphorylation of Trk receptors and promote neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23104–23110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vambutas V, Kaplan DR, Sells MA, Chernoff J. Nerve growth factor stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of Src homology-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1 in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25629–25633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrman T, He X, Raab B, Dukipatti A, Blau H, Garcia KC. Structural and mechanistic insights into nerve growth factor interactions with the TrkA and p75 receptors. Neuron. 2007;53:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weskamp G, Reichardt LF. Evidence that biological activity of NGF is mediated through a novel subclass of high affinity receptors. Neuron. 1991;6:649–663. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90067-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmann C, Ultsch MH, Bass SH, de Vos AM. Crystal structure of nerve growth factor in complex with the ligand-binding domain of the TrkA receptor. Nature. 1999;401:184–188. doi: 10.1038/43705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DE, McKinnon CA, Daou MC, Stephens RM, Kaplan DR, Ross AH. Interaction with TrkA immobilizes gp75 in the high affinity nerve growth factor receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2133–2138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SB, Timm DE, Neet KE. Alteration of NH2-terminal residues of nerve growth factor affects activity and Trk binding without affecting stability or conformation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6278–6285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff NR, Neet KE. Modulation of the neuronal binding of the beta subunit of nerve growth factor (NGF) by the alpha-NGF subunit. J Cell Biochem. 1982;19:231–240. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240190304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff NR, Neet KE. Beta nerve growth factor binding to PC12 cells. Association kinetics and cooperative interactions. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7956–7966. doi: 10.1021/bi00372a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SO, Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter B, Chao MV. Competitive signaling between TrkA and p75 nerve growth factor receptors determines cell survival. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3273–3281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03273.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]