Abstract

Background

Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor) is one of the most destructive pests of wheat. The genes encoding 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase (OPR) and lipoxygenase (LOX) play critical roles in insect resistance pathways in higher plants, but little is known about genes controlling resistance to Hessian fly in wheat.

Results

In this study, 154 F6:8 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) generated from a cross between two cultivars, ‘Jagger’ and ‘2174’ of hexaploid wheat (2n = 6 × =42; AABBDD), were used to map genes associated with resistance to Hessian fly. Two QTLs were identified. The first one was a major QTL on chromosome 1A (QHf.osu-1A), which explained 70% of the total phenotypic variation. The resistant allele at this locus in cultivar 2174 could be orthologous to one or more of the previously mapped resistance genes (H9, H10, H11, H16, and H17) in tetraploid wheat. The second QTL was a minor QTL on chromosome 2A (QHf.osu-2A), which accounted for 18% of the total phenotypic variation. The resistant allele at this locus in 2174 is collinear to an Yr17-containing-fragment translocated from chromosome 2N of Triticum ventricosum (2n = 4 × =28; DDNN) in Jagger. Genetic mapping results showed that two OPR genes, TaOPR1-A and TaOPR2-A, were tightly associated with QHf.osu-1A and QHf.osu-2A, respectively. Another OPR gene and three LOX genes were mapped but not associated with Hessian fly resistance in the segregating population.

Conclusions

This study has located two major QTLs/genes in bread wheat that can be directly used in wheat breeding programs and has also provided insights for the genetic association and disassociation of Hessian fly resistance with OPR and LOX genes in wheat.

Keywords: Hessian fly resistance, Insect resistance pathway, lipoxygenase (LOX), 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase (OPR), Quantitative trait loci (QTL), Wheat

Background

Hessian fly [Hf, Mayetiola destructor (Say)] is one of the most destructive pests of hexaploid wheat (T. aestivum L., AABBDD, 2n = 6 × =42) in the United States and worldwide [1]. Hessian fly larvae live between leaf-sheaths at seedling stage in fall, inhibit wheat growth irreversibly, and the infested plants lose vigor and die after larvae become pupae. Hessian fly larvae also attack stalks in spring, and the attacked plants may break easily before harvest. Deployment of natural and genetic resistance in locally adapted wheat cultivars is the most effective, economical, and environmentally safe method to control this devastating insect.

At least 33 Hessian fly resistance genes have been identified, designated as H1 to H32 and Hdic[2]. Among these Hessian fly resistance genes, however, only 8 genes (H1-H5, H7, H8, and H12) were identified in hexaploid wheat [3-8]. The remaining 25 genes were identified in distant and close relatives of hexaploid wheat. There are 15 genes (H6, H9–H11, H14–H20, H28, H29, H31, and Hdic) identified in tetraploid wheat species Triticum turgidum subsp. durum (AABB, 2n = 4 × =28) [9-19], and 6 of them (H6, H9-H11, H31, and Hdic) have been introgressed from tetraploid to hexaploid wheat [7,18-20]. Other genes originating in wild diploid wheat or other relatives and introgressed to hexaploid wheat include six genes (H13, H22, H23, H24, H26, and H32) from Aegilops tauschii (DD, 2n = 2 × =14) [21-25], two genes (H21 and H25) from Secale cerale L. (RR, 2n = 2 × =14) [26,27], one gene (H27) from Aegilops ventricosa (DvDvMvMv, 2n = 4 × =28, [28]), and one gene (H30) from Aegilops triuncialis (CCUU, 2n = 4 × =28) [29]. These genes provide important resistance sources but are problematic in variety development programs when they are associated with alien linkage drag.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) or microsatellite markers were used to map Hessian fly resistance genes in previous studies. Seven genes (H5, H9, H10, H11, H16, H17, and Hdic) were mapped on chromosome 1A, and these genes may comprise a cluster (or family) of Hessian fly resistance genes in the distal gene-rich region of wheat chromosome 1AS [19,20,30,31]. The remaining mapped genes include eight genes (H3, H6, H12, H14, H15, H19, H28, and H29) on chromosome 5A [10,17,32,33], three genes (H24, H26, and H32) on chromosome 3D [23-25], three genes (H18, H20 and H21) on chromosome 2B [16,26,29], two genes (H13 and H23) on chromosome 6D [23,34], H7 on chromosome 5D [35], H22 on chromosome 1D [22], H25 on chromosome 6B [27], H31 on chromosome 5B [18], and H27 on chromosome 4D [28]. Current understanding of SSR markers is that they can be effectively applied to marker-assisted selection (MAS) due to their relative simplicity. However, the ‘repeat’ feature of an SSR marker results in multiple and inconsistent locations of the same marker among divergent wheat cultivars [36]. Only a gene marker that is developed for the specific functional polymorphism of a gene responsible for a given trait can provide the ultimate resolution needed for selection of the trait [37].

The best strategy to find the regulatory sites of a gene is to clone the gene/QTL. The cloned gene is then used to develop perfect gene markers for use in conventional breeding programs or to manipulate transgenic wheat. To date, 14 genes have been cloned from wheat using the positional cloning strategy [38,39], but no gene has been cloned for resistance to Hessian fly. To clone a gene from hexaploid wheat using the map-based cloning approach remains a challenge because of the complexity imparted by three homoeologous genomes, the large genome size (17 Gb), high content of repetitive sequences (>80%), and the low polymorphism rate [40-43]. In recent studies, genetic association is also use to identify functional genes for important traits in wheat [44].

Recent progress in the application of high-throughput sequencing technologies and development of sophisticated genomic mapping tools has accelerated identification of agriculturally important genes in wheat. Numerous wheat ESTs assigned to wheat deletion bins have facilitated the physical mapping of a gene [45,46]. The availability of genomic sequences from the model species rice [45] and Brachypodium distachyon[47], and synteny conservation in certain genomic regions between these species and wheat [48,49] have allowed more precise determination of the physical distance between two markers flanking the target gene by a comparative genomics analysis. Newly available wheat genomic sequences, though at low coverage (http://www.cerealsdb.uk.net/), are useful for designing primers specific to a homoeologous gene for genomic mapping. With the integration of these techniques and tools, mutants of several genes including VRN-A1[50], VRN-D3[50], PPD-D1[50], Lr34-D[51], Yr17[52], and Pm3[37] have been identified in cultivated bread wheat. These genes each were initially mapped under the peak of a QTL for a relevant trait and their mutants were eventually confirmed. In this study, we aimed to determine if any genes known to confer insect resistance in plants are associated with a QTL for resistance in our mapping populations or in a genomic region where a QTL has been reported in published mapping populations.

Plants possess multiple defense mechanisms in response to mechanical damage due to insect attack. Jasmonic acid (JA) and its conjugates, jasmonates, play a central role in regulating defense responses of plants to insect herbivores [53]. In higher plants, JA is synthesized via the octadecanoid pathway consisting of several enzymatic steps. The early steps of this pathway occur in chloroplasts where linolenic acid is converted to 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) by means of three enzymes, lipoxygenase (LOX), allene oxide synthase (AOS), and allene oxide cylase [54-56]. OPDA is subsequently reduced in a cyclopentenone ring by a peroxisome-localized enzyme, 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase 3 (OPR3). The reaction product then undergoes three cycles of oxidation in the peroxisome, generating JA [57-59].

In this study, we mapped 3 OPR genes and 3 LOX genes in a population of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) that was generated from a cross between two locally adapted winter cultivars, ‘Jagger’ and ‘2174’, and showed demonstrable segregation for resistance to Hessian fly. The implication in association and disassociation of the QTLs for resistance to Hessian fly with these OPR and LOX genes is discussed.

Results

QTLs mapped for wheat resistance to Hessian fly

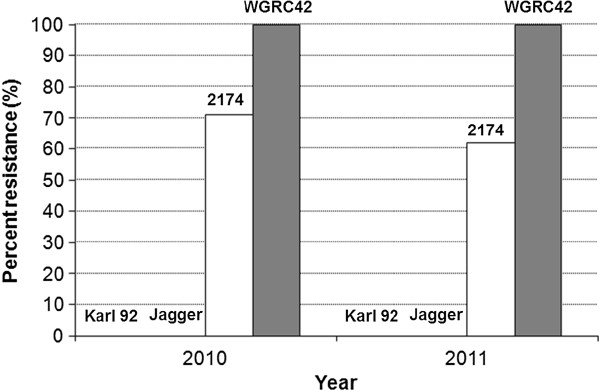

Jagger was highly susceptible and 2174 was highly resistant to Hessian fly biotype GP when the two parental lines were tested with susceptible (Karl 92) and resistant (WGRC42) cultivars as controls (Figure 1). Hence variation in Hessian fly resistance between the two parental lines should facilitate mapping the resistance trait based on segregation in the available population of F6:8 RILs generated by crossing the parental cultivars.

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of Hessian fly resistance among hexaploid wheat cultivars. Ratings were scored [67] for two-years for Jagger and 2174 used as the parental lines to generate RILs. Karl 92 and WGRC42 were used as susceptible and resistant controls, respectively.

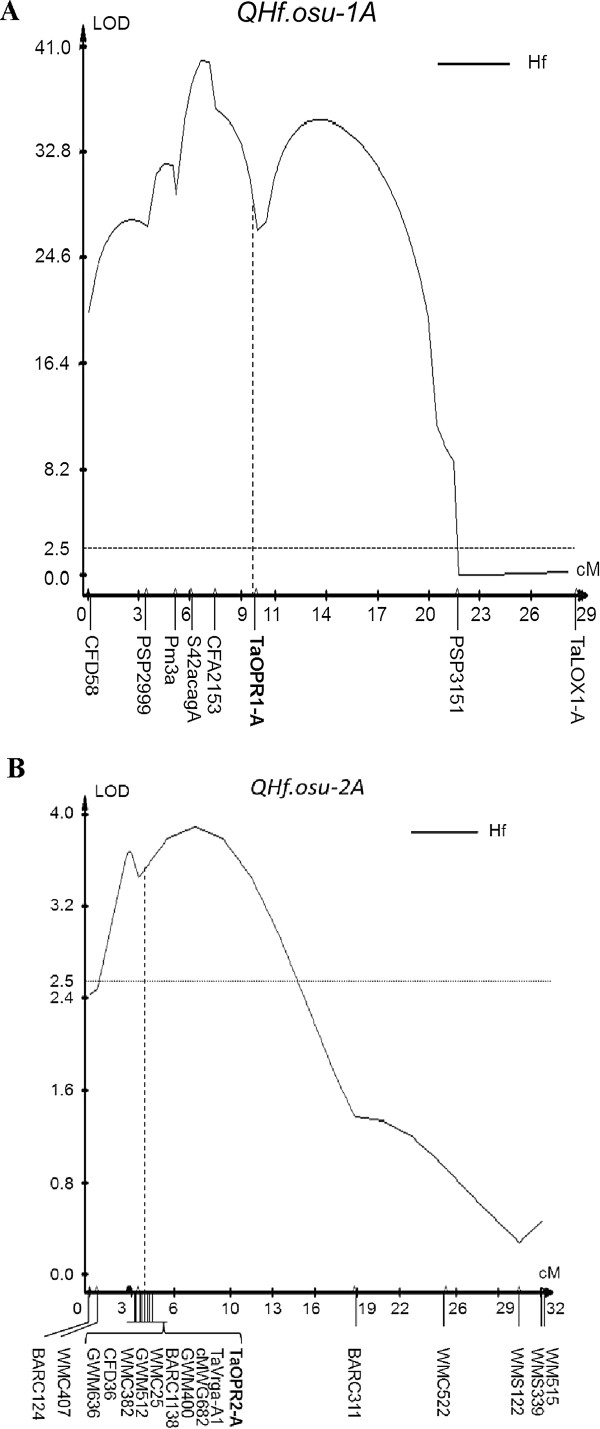

Using 154 RILs of the Jagger × 2174 population and genome-wide SSR markers [52], we mapped two QTLs linked with Hessian fly resistance. The first one was a major QTL on the distal end of chromosome 1AS (QHf.osu-1A) (Figure 2A), when the population was infested with the same biotype as the parental lines. QHf.osu-1A was mapped in tight linkage with the powdery mildew gene Pm3a previously identified [37]. The LOD value for QHf.osu-1A was 28.7, which explained 70% of the total phenotypic variation. Phenotypic data showed that those RILs which carried the Jagger allele had resistance at the level of 6%, whereas those RILs that carried the 2174 allele had resistance at the level of 59%. 2174 has a resistant allele for both Hessian fly and powdery mildew (Pm3a) genes.

Figure 2.

Mapping of two QTLs for resistance to Hessian fly. Response to Hessian fly for each of 154 RILs was scored in the Jagger × 2174-derived RIL population using the method previously described [67]. QTL analysis was performed with composite interval mapping (CIM) using WinQTLCart 2.5. The positions of marker loci are shown on the x-axis in centiMorgan (cM) distances. The horizontal dotted line indicates the logarithm of the odds (LOD) significance threshold of 2.5. The vertical dash line indicates the gene markers associated with the QTLs.

The second QTL was a minor QTL on chromosome 2A (QHf.osu-2A) (Figure 2B). The peak of this QTL was associated with a group of several tightly linked SSR markers and the marker for Yr17 that was translocated from chromosome 2N of Triticum ventricosum (2n = 4 × =28; DDNN) in Jagger [52,60]. The LOD value for QHf.osu-2A was 3.5 and this QTL accounted for 18% of the total phenotypic variation. Phenotypic data showed that those RILs which carried the Jagger allele had resistance at the level of 23.1%, whereas those RILs that carried the 2174 allele had resistance at the level of 51.9%. The resistant allele at this locus in 2174 is collinear to an Yr17-containing-fragment translocated from chromosome 2N in Jagger. Jagger attained the translocated chromosome 2N fragment conferring resistance to stripe rust [52]. If the translocated fragment in Jagger was introgressed into a breeding line or a cultivar such as 2174, the novel breeding line could lose approximately 60% of Hessian fly resistance conferred by the OPR2-A gene on chromosome 2A in 2174.

Associations of QTLs for Hessian fly resistance with two OPR genes

The peak of QHf.osu-1A was centered with SSR marker Xcfa2153 (Figure 2A), which was physically located in a deletion bin of 1AS-3 (FL 0.86), or the distal 14% of the short arm of chromosome 1A [61]. Wheat EST BE403717 encoding an OPR protein was also found present in this 1AS-3 FL 0.86 deletion bin. It is thus intuitive to hypothesize that this OPR gene may be a candidate gene for QHf.osu-1A if it is mapped under the peak of this QTL. The BE403717 sequence was used to blast against the wheat genomic DNA databases (http://www.cerealsdb.uk.net), and the wheat sequences retrieved from the databases were grouped based on sequence alignments of the homoeologous and paralogous OPR genes. Primers were designed for each group of these genes and tested for specificity to N1AT1D, N1BT1D, and N1DT1B of ‘Chinese Spring’ (CS) nullisomic–tetrasomic (NT) lines [62]. Primers OPRC1-ABD-F2 and OPRC1-R8 for one of the OPR genes were identified specific to chromosome 1A (Figure 3A).

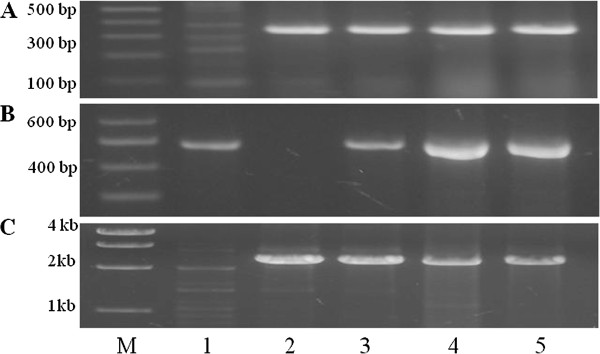

Figure 3.

Gene markers tested on N1AT1D, N1BT1D, and N1DT1B of CS nullisomic–tetrasomic lines. PCR products amplified for TaOPR1-A, TaLOX1-A, and TaOPR7-B. Lanes: 1 N1AT1D, 2 N1BT1D, 3 N1DT1B, 4 Jagger, 5 2174. M Molecular marker. A) TaOPR1-A marker. PCR was performed using primers OPRC1-ABD-F2 and OPRC1-R8. B) TaOPR7-B marker. PCR was performed using primers OP1-C1F1 and OP1-R1. C) TaLOX1-A marker. PCR was performed using primers LOX-C5-F5 and LOX-C5-R6. Expected size of PCR products was indicated in Table 1.

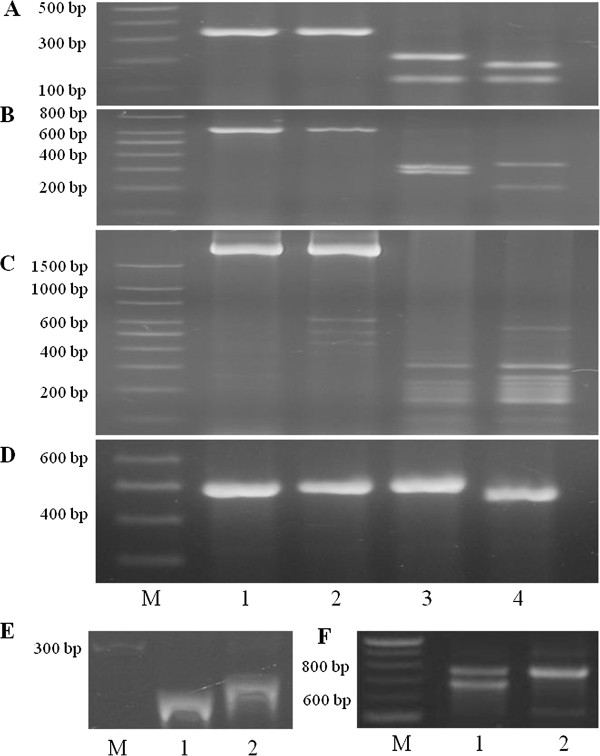

A PCR marker, using primers OPRC1-ABD-F2 and OPRC1-R8, was developed for the OPR gene TaOPR1-A, the first OPR gene to be mapped on chromosome 1A of T. aestivum. The primers amplified a 337-bp fragment that was digested with KpnI into 213 bp and 124 bp for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035075) and into 36 bp, 177 bp, and 124 bp for the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035076) (Figure 4A). TaOPR1-A was mapped under the peak of QHf.osu-1A and 2.4 cM in genetic distance to Xcfa2153 (Figure 2A) in the RIL population of Jagger × 2174.

Figure 4.

PCR markers for six OPR and LOX genes, TaOPR1-A, TaOPR2-A, TaLOX1-A, TaOPR7-B, TaLOX6-B, and TaLOX2-B. A-F) Lanes: 1 undigested Jagger 2 undigested 2174 3 digested Jagger 4 digested 2174. M Molecular marker. A) TaOPR1-A marker. Digestion with KpnI shows polymorphic band patterns for Jagger (213 bp + 124 bp) and 2174 (36 bp + 177 bp + 124 bp) (the 36 bp band was run out of the gel). B) TaOPR2-A marker. Digestion with HincII shows polymorphic band patterns for Jagger (20 bp + 321 bp + 292 bp) and 2174 (342 bp + 215 bp + 77 bp) (the 20 bp and 77 bp bands were run out of the gel). C) TaLOX1-A marker. Digestion with ScrFI shows polymorphic band patterns for Jagger and 2174, in which 2174 has an extra ~250 bp fragment. D) TaOPR7-B marker. Digestion with DdeI shows polymorphic band patterns for Jagger (487 bp) and 2174 (35 bp + 452 bp) (the 35 bp band was run out of the gel). E) TaLOX6-B marker. PCR products show polymorphic band patterns for Jagger and 2174 with 8-bp indels. F) TaLOX2-B marker. PCR products show polymorphic band patterns for Jagger and 2174 with an extra lower band in Jagger. PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel (A-D and F) or 6% acrylamide gel (E).

The second OPR gene, TaOPR2-A, which showed 79% identity (Additional file 1) to TaOPR1-A within a range of 584 bp (E = 2e-112), showed complete linkage with a group of markers for Yr17 translocated from chromosome 2N and under the peak of QHf.osu-2A. The wheat EST BE403717 that was mapped in 1AS-3 FL 0.86 deletion bin was used to blast against GenBank Nucleotide Collection (nr/nt) databases, and it showed 82% identity within a range of 318 bp (E = 1e-83) to an orthologous OPR gene in rice BAC from chromosome 6 (GenBank: AP004741). Specific primers were designed based on the grouped sequences retrieved from the wheat genomic DNA databases. The primers OPR22-C1-F3 and OPR-R2 amplified a 634 bp fragment that was digested with HincII into 20 bp, 321 bp and 292 bp for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035084) and into 342 bp, 215 bp, and 77 bp for the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035085) (Figure 4B).

Disassociations of OPR and LOX genes with mapped QTLs for Hessian fly resistance

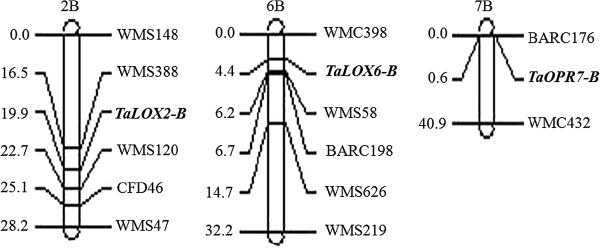

In addition to the mapped associations of TaOPR1-A and TaOPR2-A with the two QTLs for Hessian fly resistance, another OPR gene TaOPR7-B was linked with Xbarc176 on chromosome 7B (Figure 5A). Initially, an OPR gene present in rice BAC (GenBank: AP004707) was analyzed and used to search for the wheat orthologous OPR genes, because the rice BAC could be in a collinear region to wheat chromosome 1A. Specific forward primer OPR1-C1F1 was used to combine with conserved reverse primer OPR-R1 to amplify a single copy of the OPR gene mapped on chromosome 7B (TaOPR7-B). The chromosomal location of TaOPR7-B was confirmed by using CS nullisomic-tetrasomic lines (Figure 3B). The primers OPR-C1F1 and OPR-C1R1 amplified a 487 bp fragment that was digested with DdeI for the 2174 allele into 35 bp (GenBank: KF035087) and 452 bp but was not digested for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035086) (Figure 4D).

Figure 5.

Genetic maps of the TaOPR7-B, TaLoX2-B, and TaLOX6-B genes. TaOPR7-B was mapped on chromosome 7B (A), TaLOX2-B was mapped on chromosome 2B (B), and TaLOX6-B was mapped on chromosome 6B (C). Approximate distances in centi-Morgans (cM) and molecular markers are indicated on the left and the right, respectively.

Three LOX genes were mapped in this study. Initially, a wheat EST (GenBank: BF482663) that was mapped in the 1AS-3 FL 0.86 deletion bin was used to blast against wheat gDNA databases (http://www.cerealsdb.uk.net) and GenBank EST databases for the homoeologous and paralogous LOX genes. This wheat EST was expected to reside in a region collinear with rice chromosome 5[45]. It showed 86% identity within a range of only 43 bp (E = 7e-05) to an orthologous gene in rice BAC from chromosome 5 (GenBank: AC136525), but it was more likely orthologous to other LOX genes in rice, with 87% identity in a range of only 294 bp (E = 5e-96) to one in chromosome 2 (GenBank: AP004184), with 72% identity (E = 2e-38) to two genes on chromosome 8 (GenBank: AP005816). Homoeologous chromosomes of hexaploid wheat could have three genes for each orthologous gene in rice. Primers were designed specifically to each of the groups retrieved from the sequences by BF482663.

The first LOX gene was mapped using primers LOX-C5-F5 and LOX-C5-R6 specific to chromosome 1A (Figure 3C). The primers amplified a fragment of approximately 2,500 bp that was digested with ScrFI into several fragments, distinguishable by an extra fragment of approximately 250 bp for the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035089) compared with the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035088) (Figure 4C). This LOX gene was mapped on chromosome 1A (TaLOX1-A) but outside of the QHf.osu-1A region (Figure 2A).

The second LOX gene was mapped using primers LOX0-F4 and LOX0-R6 that amplified a common band in both Jagger and 2174 and an additional lower band in Jagger (Figure 4F). PCR products from Jagger were purified from the agarose gel, and direct sequence analysis showed that it was part of a LOX gene (Additional file 2). The high quality sequence result indicated that it was from a pseudo gene in Jagger (GenBank: KF035090). The dominant marker for the LOX gene in Jagger was mapped with a linkage group of SSR markers on chromosome 2B (Figure 5B), and this gene was thus designed TaLOX2-B.

The third LOX gene was mapped using primers LOX-F4 and LOX-R6 that amplified PCR products of polymorphic size with approximately 264 bp in Jagger (GenBank: KF035091) and 272 bp in 2174 (GenBank: KF035092). The sequencing results confirmed that these PCR products were derived from part of a LOX gene, with an 8 bp deletion for the Jagger allele or an 8 bp insertion for the 2174 allele (Figure 4E). This LOX gene was mapped with a linkage group of SSR markers on chromosome 6B (Figure 5C), and this gene was thus designed TaLOX6-B.

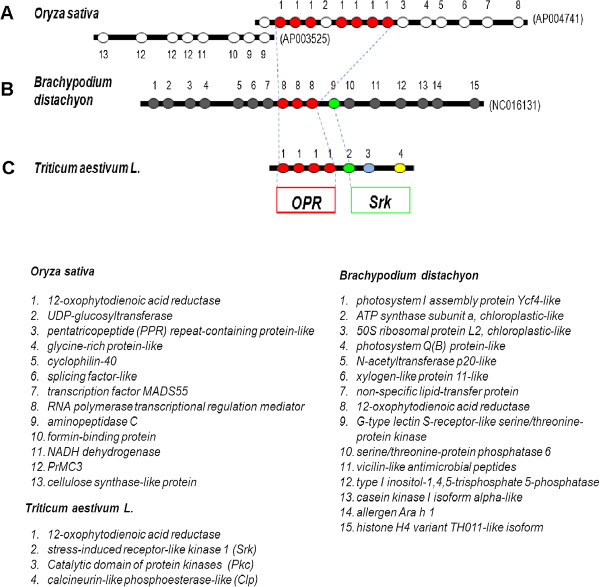

Fine collinearity at the QHf.osu-1A locus between wheat, rice and Brachypodium

TaOPR1-A was used to screen the T. durum BAC library, and one positive clone (73J24) was sequenced with low coverage to find genes that could be used to determine collinear regions of rice and Brachypodium. Four OPR genes (GenBank: KF035074, KF035077, KF035080, and KF035081), and three genes encoding stress-induced receptor-like kinase (Srk) (GenBank: KF035093), catalytic domain of protein kinases (Pkc) (GenBank: KF035099), and calcineurin-like phosphoesterase-like (Clp) (GenBank: KF035096) respectively, were present in the wheat BAC clone (Figure 6C). Allelic variation was observed in the Srk gene for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035094) and the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035095), the Clp gene for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035097) and the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035098), and the Pkc gene for the Jagger allele (GenBank: KF035100) and the 2174 allele (GenBank: KF035101). Howerver, no crossover was found between the OPR genes and these linked genes in the the QHf.osu-1A region.

Figure 6.

Comparative map of the wheat OPR region on chromosome 1AS and in collinear regions from Brachypodium and rice. The flanking genes for the OPR region in rice and Brachypodium are colored in white and grey, respectively. Flanking genes, Srk, Pkc, and Clp in wheat, are colored in green, blue, and yellow, respectively. Dotted lines indicate synteny of genes among wheat, rice, and Brachypodium.

TaOPR1-A displayed the highest identity to orthologous OPR genes in a rice BAC from chromosome 6 (GenBank: AP004741), which contains 7 OPR genes arranged in tandem (Figure 6A). Except for the wheat OPR genes, however, the other wheat genes (Srk, Clp, and Pkc) were not present in the flanking regions of the OPR genes in the two BAC clones shown in Figure 6A or in other BAC clones containing OPRs in rice. TaOPR1-A displayed the highest identity to three orthologous OPR genes in Brachypodium (GenBank: NC016131, Figure 6B), but again, except for the wheat OPR genes and Srk gene, the other wheat genes (Clp and Pkc) were not observed in the collinear region of Brachypodium. The orthologous genes in Brachypodium were not present in the flanking regions of the OPR genes in rice either.

Discussion

A resistance gene against Hessian fly has been repeatedly mapped to the end of the short arm of chromosome 1A in previous studies, and it was suggested that this genomic region contained a cluster of major dominant resistance genes against multiple Hessian fly biotypes, including H5, H9, H10, H11, H16, H17, and Hdic[19,20,30,31]. However, all of the previous studies were performed in the tetraploid wheat T. durum. Our study is the first report that a resistance gene against Hessian fly exists in the short arm of chromosome 1A in bread wheat. The resistance gene at the QHf.osu-1A locus observed in hexaploid wheat cv. 2174 could be orthologous to one or more of the previously mapped resistance genes in tetraploid wheat. This study provides an effective resistance source to manage biotype GP that frequently damage bread wheat cultivars in the southern Great Plains. Further studies need to test if the QHf.osu-1A gene is allelic to genes H16 and H17 that confer resistance against Hessian fly biotype L, the most virulent and prevalent biotype in the eastern USA [31]. The resistance gene at QHf.osu-1A in 2174 and its derived cultivars can be immediately utilized to control Hessian fly biotype GP in winter wheat improvement programs in the southern Great Plains in USA. The gene may also be useful for pyramiding to prolong the effective periods of other resistance genes.

Mapping of QHf.osu-1A showed that it is closely linked with Pm3a. Previous studies indicated that Pm3 was linked to H9 at a genetic distance of 4.5 cM [61]. Several alleles have been characterized for the Pm3 gene [63]. Leaf rust resistance gene Lr10, which has three paralogous genes and is effective against Puccinia triticina Eriks, was also mapped in the same chromosomal region on 1AS [64,65]. The presence of a resistance gene cluster in the gene-rich distal region of 1AS in bread wheat has made it difficult to determine which gene is the candidate for QHf.osu-1A. An effort was made to construct a fine physical map for QHf.osu-1A. However, low collinearity of the gene order in this region among wheat, rice, or Brachypodium indicates that the fine physical map for QHf.osu-1A cannot be established by using genome information from rice or Brachypodium only. The recent sequencing of wheat genomes may provide a powerful tool in cloning QHf.osu-1A.

Two OPR genes were identified in association with two QTLs for resistance against Hessian fly, but we cannot yet decisively conclude if either of the candidate OPR genes is responsible for QHf.osu-1A. The two QTLs were discovered in the same population, and resistance to Hessian fly is inseparable between the two QTLs. Two specific RIL lines (#23 and #26) have been selected to backcross with the 2174 parental line to generate progeny that will segregate for a single Hessian fly gene. In these backcross populations, QHf.osu-1A will occur in the heterozygous state, whereas QHf.osu-2A will be fixed in a homozygous genetic background. We expect that the two alleles of QHf.osu-1A will produce clear segregation for resistance to Hessian fly. BC1F2-3 populations will be used also to determine degree of dominance for the Hessian fly gene.

TaLOX6-B was mapped between Xwmc398 and Xbarc198 toward the centromere of wheat chromosome 6B. It was reported that H25 was translocated from rye to the long arm of chromosome 6B of wheat [27], and thus, TaLOX6-B is not allelic to H25. TaLOX2-B is located between Xwms388 and Xwms120 on the long arm of chromosome 2B. H20 was transferred from T. durum to chromosome 2B, and H21 was translocated from rye to chromosome 2B in wheat. However, more information is needed to further clarify any allelic relationship of TaLOX6-B with either H20 or H21. A recent study indicates that a novel wheat gene encoding a lectin-like protein (Hfr-3) was associated with response to Hessian fly [66]. The homoeologous Hfr-3 genes are located on group 7 chromosomes of the hexaploid wheat. Yet, no Hessian fly resistance gene was reported on chromosome 7B where TaOPR7-B was mapped.

Conclusions

In summary, a frequent objective of wheat breeding is to pyramid multiple genes for resistance to diseases and insects into a single cultivar. Compared with 2174, Jagger attained a translocated fragment that contains Lr37, Yr17 and Sr38 conferring resistance to leaf rust, stripe rust, and stem rust, but Jagger lost the allelic region containing the resistance gene on QHf.osu-2A against Hessian fly. The molecular marker can greatly facilitate the identification of such a candidate gene for the QHf.osu-1A locus, enabling opportunities for functional analysis which can then be used to better understand the defense mechanisms of wheat plants in response to this major insect.

Methods

Hessian fly populations

A Kansas population of Hessian fly consisting of predominantly biotype GP [67] was used in this study. The population was maintained on Hessian fly susceptible wheat seedlings (‘Karl 92’) in the greenhouse. Karl 92 was used as a susceptible control and WGRC42 was used as a resistant control to test the Hessian fly population [19].

Plant materials and DNA isolation

Based on observations on seedling plants, Jagger is susceptible to Hessian fly biotype GP infestation whereas 2174 is resistant; therefore, the Jagger × 2174 population of 154 F6:8 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) were used to map genes associated with resistance to Hessian fly. Wheat genomic DNA was extracted from leaf tissue of each RIL plant as described previously [68].

Evaluation of Hessian fly resistance

Parental lines and 154 F6:8 RILs were evaluated for phenotypic reaction to Hessian fly infestation in growth chambers at 18 ± 1°C with a 14 h:10 h (light: dark) photoperiod as described previously [20,34,69]. Briefly, seedling plants were infested with mated Hessian fly females. Three weeks after infestation, seedling plants were examined to identify resistant and susceptible phenotypes. Susceptible plants were stunted, dark green, and harbored live larvae, whereas resistant plants grew normally with light green color and dead larvae [67]. Hessian fly reactions were recorded and a random subset of the RILs was confirmed with additional replications (three totally).

Resistance screening was carried out in greenhouse as described previously [19]. Specifically, approximately 20 seeds of each wheat line were planted in a flat. A flat with soil was divided into 22 rows with a line divider, and each row was further divided into two half rows. Therefore in each flat, a total of 44 wheat lines could be planted. Along with wheat lines from a mapping population, two susceptible control wheat lines, Karl 92 and Jagger (the susceptible parent), and two resistant control wheat lines, 2174 (putative resistant donor) and WGRC42 (containing the R gene Hdic), were also planted in each flat. Wheat plants were infested at one leaf-stage (the second leaf just emerged) with Hessian fly adults under a cheese cloth tent. Females deposit eggs on the adaxial surface of the first leaf. Infestation was stopped when the egg density reaches 8 per leaf, which usually results in ~5 larvae per plant. Resistant and susceptible plants were phenotyped three weeks after infestation. Phenotypes of resistant and susceptible plants were distinct and easy to score. Resistant plants grew normally with light green color and susceptible plants were stunt with dark-green color. Plants with a resistant phenotype were further dissected to check for dead larvae. Plants without dead larvae were taken as escapes and were excluded from the data set.

QTL analysis

A total of 404 SSR markers were assembled in linkage groups using MapMaker 3.0 program, and a QTL was identified using the WinQTLCart 2.5 program as previously described [37,70]. Other unlinked markers were tested using correlation analysis to examine which markers might be related to Hessian fly resistance using SAS software (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Gene-specific marker development

Wheat ESTs encoding LOX (GenBank: BE403717) and OPR (GenBank: BE482663) were found present in the deletion bin (1AS-3 FL 0.86) on chromosome 1A, and these ESTs were used to develop markers for mapping. The genomic sequences of the orthologous OPR and LOX genes in rice are available in GenBank databases, including OPR genes in rice BAC from chromosome 1 (GenBank: AK100034), chromosome 6 (GenBank: AP004741), and chromosome 8 (GenBank: AP004707); and LOX genes from chromosome 2 (GenBank: AP004184), chromosome 5 (GenBank: AC136525), and chromosome 8 (GenBank: AP005816). Rice BACs and wheat EST sequences were used to blast against wheat gDNA databases (http://www.cerealsdb.uk.net) to retrieve homoeologous and paralogous sequences for each TaOPR and TaLOX genes. Multiple sequence alignments showed that the homoeologous and paralogous TaOPR and TaLOX genes are variable, which made it possible to design genome-specific primers for each gene. Gene markers developed were used to analyze the RIL population and evaluated for linkage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used for detecting allelic variation in TaOPR1-A, TaOPR2-A, TaOPR7-B, TaLOX1-A, TaLOX2-B, TaSrk, TaClp, and TaPkc in hexaploid wheat

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Loci | PCR size (bp) | Tm (°C) | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPRC1-ABD-F2 |

CCGTCGACGCCGGTACG |

TaOPR1-A |

337 |

62 |

Kpnl |

| OPRC1-R8 |

GGCCGCCGATCTCCCT |

TaOPR1-A |

|

|

|

| OPR22-C1-F3 |

TCTGCTTTCCTCTGCTCGTC |

TaOPR2-A |

634 |

55 |

Hincll |

| OPR-R2 |

TTCATGGTTCAATGACACATCAAGG |

TaOPR2-A |

|

|

|

| OP1-C1F1 |

AAAAGGTTTTCACCTCGATGATCGGGG |

TaOPR7-B |

487 |

55 |

Ddel |

| OP1-R1 |

CCGATGGCCCTGCACCTCGTCATCG |

TaOPR7-B |

|

|

|

| LOX-C5-F5 |

CATCCTGAATAAAGAACCTC |

TaLOX1-A |

2500a |

55 |

ScrFl |

| LOX-C5-R6 |

GATCATATGGAGACGCTGTT |

TaLOX1-A |

|

|

|

| LOX0-F4 |

GGAGCACGGCCTCAAGCTC |

TaLOX2-B |

680a |

52b |

dominant band |

| LOX0-R6 |

CATGTGGTTTATTTTAGCTCTGTAGA |

TaLOX2-B |

|

|

|

| LOX-F4 |

CTGCGTCGAGCCCTACATCATCG |

TaLOX6-B |

264/272 |

62 |

8-bp indels |

| LOX-R6 |

GGGCCAGCCCCCGGCTGACG |

TaLOX6-B |

|

|

|

| Srk-F3 |

CGGACCACTTCAACCATAGG |

TaSrk |

1437 |

56 |

|

| Srk-R2 |

ACCTTTCACAGTCTGCAATGGCAATGCT |

TaSrk |

|

|

|

| CLP-F1 |

TCCATCTCCTATGGCTTCTT |

TaClp |

1648 |

55 |

Rsal |

| CLP-R2 |

GGTGGGGGTTGCCTATCCAG |

TaClp |

|

|

|

| Pkc-F3 |

GAGAGAAGCAATTCAGGGCT |

TaPkc |

911 |

55 |

|

| Pkc-R2 | CCAGATTACAATTTTAAAGAGAAG | TaPkc |

a Estimated product size.

b A touch-down program (60°C down to 52°C for annealing temperature) was performed before the regular was performed (see details in Methods).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

All PCR reactions were performed in a 25 μl reaction under the following conditions: 1 denaturation cycle at 94°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52-62°C (based on primer annealing temperature) for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s – 2.5 min (based on fragment length), then a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min before cooling to 4°C. PCR amplified fragments were separated on 2% agarose gels through electrophoresis in 1× TAE buffer or 6% acrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer. DNA banding patterns were visualized under UV light with ethidium bromide staining.

Abbreviations

OPR: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase; LOX: Lipoxygenase; RILs: Recombinant inbred lines; QTL: Quantitative trait loci; Hf: Hessian fly; SSR: Simple sequence repeat; JA: Jasmonic acid; OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; AOS: Allene oxide synthase; OPR3: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase 3; GP: Great plains; EST: Expressed sequence tag; BAC: Bacterial artificial chromosome; gDNA: Genomic DNA; Srk: Induced receptor-like kinase; Pkc: Catalytic domain of protein kinases; Clp: Calcineurin-like phosphoesterase-like.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CTT performed the experiments and analyzed data. BFC provided plant materials for the project and helped edit the manuscript. MSC performed phenotype experiments for Hessian fly resistance. YQG performed analysis of comparative genomics and provided BAC clones. CTT and LY designed the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Sequence comparison of TaOPR1-A and TaOPR2-A.

Sequence comparison of a LOX gene between wheat and rice.

Contributor Information

Chor Tee Tan, Email: tct83@hotmail.com.

Brett F Carver, Email: brett.carver@okstate.edu.

Ming-Shun Chen, Email: mchen@ksu.edu.

Yong-Qiang Gu, Email: yong.gu@ars.usda.gov.

Liuling Yan, Email: liuling.yan@okstate.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by USDA-NIFA T-CAP grant No. 2011-68002-30029, the Oklahoma Center of Advanced Science and Technology (OCAST, PAS07-002), and the Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation.

References

- Porter D, Harris MO, Hesler LS, Puterka GJ. In: Wheat: Science and Trade. Carver BF, editor. New York: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. Insects which challenge global wheat production; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh RA, Yamazaki Y, Devos KM, Dubcovsky J, Rogers J, Appels R. Catalogue of gene symbols. Mac-Gene 2012. Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan: National Institution of Genetics; 2012. http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/wheat/komugi/genes/macgene/2012/GeneSymbol.pdf;jsessionid=C70274C2F26D17832AB26758A1F00C08.lb1. [Google Scholar]

- Noble WB, Suneson JA. Differentiation of the two genetic factors for resistance to Hessian fly in Dawson wheat. J Agri Res. 1943;67:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell RM, Cartwright WB, Compton LE. Inheritance of Hessian fly resistance derived from W38 and durum P.I.94587. J Am Soc Agro. 1946;38:398–409. doi: 10.2134/agronj1946.00021962003800050003x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suneson JA, Noble WB. Further differentiation of genetic factors in wheat for resistance to the Hessian fly. US Dep Agric Tech Bull. 1950;1004:8pp. [Google Scholar]

- Shands RG, Cartwright WB. A fifth gene conditioning Hessian fly response in common wheat. Agro J. 1953;45:302–307. doi: 10.2134/agronj1953.00021962004500070007x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallun RL, Patterson FL. Monosomic analysis of wheat for resistance to Hessian fly. J Heredity. 1977;68:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Oellermann CM, Patterson FL, Gallun RL. Inheritance of resistance in Luso wheat to Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1983;23:221–224. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1983.0011183X002300020007x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allan RE, Heyne EG, Jones ET, Johnston CO. Genetic analysis of ten sources of Hessian fly resistance, their interrelationships and association with leaf rust reaction in wheat. Kansas Agri Exp Station Tech Bull. 1959;104:54pp. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins NB, Patterson FL, Gallun RL. Interrelationships among wheat genes H3, H6, H9, and H10 for Hessian fly resistance. Crop Sci. 1982;22:1029–1032. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1982.0011183X002200050032x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins NB, Patterson FL, Gallun RL. Inheritance of resistance of PI 94587 wheat to biotypes B and D of Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1983;23:251–253. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1983.0011183X002300020016x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maas FB, Patterson FL, Foster JE, Ohm HW. Expression and inheritance of resistance of ELS6404-160 durum wheat to Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1989;29:23–28. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1989.0011183X002900010005x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson FL, Foster JE, Ohm HW. Gene H16 in wheat for resistance to Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1988;28:652–654. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800040018x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obanni M, Patterson FL, Foster JE, Ohm HW. Genetic analyses of resistance of durum wheat PI 428435 to the Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1988;28:223–226. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800020007x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obanni M, Ohm HW, Foster JE, Patterson FL. Genetics of resistance of PI 422297 durum wheat to the Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1989;29:249–252. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1989.0011183X002900020001x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amri A, Cox TS, Gill BS, Hatchett JH. Chromosomal location of the Hessian fly resistance gene H20 in ‘Jori’ durum wheat. J Heredity. 1990;81:71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cebert E, Ohm H, Patterson F, Ratcliff R, Cambron S. Genetic analysis of Hessian fly resistance in durum wheat. Agro Abstracts. 1996;88:88. [Google Scholar]

- Williams CE, Collier CC, Sardesai N, Ohm HW, Cambron SE. Phenotypic assessment and mapped markers for H31, a new wheat gene conferring resistance to Hessian fly (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) Theor App Gen. 2003;107:1516–1523. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Brown-Guedira GL, Hatchett JO, Chen M. Genetic characterization and molecular mapping of a Hessian fly-resistance gene transferred from T. turgidum ssp. dicoccum to common wheat. Theor App Gen. 2005;111:1308–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Fritz AK, Reese JC, Wilde GE, Gill BS, Chen M. H9, H10, and H11 compose a cluster of Hessian fly resistance genes in the distal gene-rich region of wheat chromosome 1AS. Theor App Gen. 2005;110:143–148. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1982-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill BS, Hatchett JH, Raupp WJ. Chromosomal mapping of Hessian fly-resistance gene H13 in the D genome of wheat. J Heredity. 1987;78:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Liu X, Chen M. H22, a major resistance gene to the Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor), is mapped to the distal region of wheat chromosome 1DS. Theor App Gen. 2006;113:1491–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0396-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill BS, Wilson DL, Raupp JH, Cox TS, Amri A, Sears RG. Registration of KS89WGRC3 and KS89WGRC6 Hessian fly-resistant hard red winter wheat germplasm. Crop Sci. 1991;31:245. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100010079x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Xu S, Harris M, Hu J, Liu L, Cai X. Genetic characterization and molecular mapping of Hessian fly resistance genes derived from Aegilops tauschii in synthetic wheat. Theor App Gen. 2006;113:611–618. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardesai N, Nemacheck JA, Subramanyam S, Williams CE. Identification and mapping of H32, a new wheat gene conferring resistance to Hessian fly. Theor App Gen. 2005;111:1167–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cainong JC, Zavatsky LE, Chen MS, Johnson J, Friebe B, Gill BS, Lukaszewski AJ. Wheat-rye T2BS2BL-2RL recombinants with resistance to Hessian fly (H21) Crop Sci. 2010;50:920–925. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.06.0310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friebe B, Hatchett JH, Gill BS, Mukai Y, Sebesta EE. Transfer of Hessian fly resistance from rye to wheat via radiation-induced terminal and intercalary chromosome translocations. Theor App Gen. 1991;83:33–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00229223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delibes A, Del Moral J, Martín-Sanchez JA, Mejias A, Gallego M, Casado D, Sin E, López-Braña I. Hessian fly-resistance gene transferred from chromosome 4Mv of Aegilops ventricosa to Triticum aestivum. Theor App Gen. 1997;94:858–864. doi: 10.1007/s001220050487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sanchez JA, Gomez-Colmenarejo M, Del Moral J, Sin E, Montes MJ, Gonzalez-Belinchon C, Lopez-Brana I, Delibes A. A new Hessian fly resistance gene (H30) transferred from the wild grass Aegilops triuncialis to hexaploid wheat. Theor App Gen. 2003;106:1248–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweikat I, Ohm H, Paterson F, Cambron S. Identification of RAPD markers for 11 Hessian fly resistance genes in wheat. Theor App Gen. 1997;94:419–423. doi: 10.1007/s001220050431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Cambron SE, Ohm HW. Hessian fly resistance genes H16 and H17 are mapped to a resistance gene cluster in the distal region of chromosome 1AS in wheat. Mol Breed. 2008;21:183–194. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9119-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm HW, Sharma HC, Patterson FL, Ratcliffe RH, Obanni M. Linkage relationships among genes on wheat chromosome 5A that condition resistance to Hessian fly. Crop Sci. 1995;35:1603–1607. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1995.0011183X003500060014x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm HW, Ratcliffe RH, Patterson FL, Cambron SE. Resistance to Hessian fly conditioned by genes H19 and proposed gene H27 of durum wheat line PI422297. Crop Sci. 1997;37:113–115. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1997.0011183X003700010018x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Gill BS, Chen M. Hessian fly resistance gene H13 is mapped to a distal cluster of resistance genes in chromosome 6DS of wheat. Theor App Gen. 2005;111:243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-2009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amri AT, Cox TS, Hatchett JH, Gill BS. Complementary action of genes for Hessian fly resistance in the wheat cultivar ‘Seneca’. J Heredity. 1990;81:1224–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Somers DJ, Isaac P, Edwards K. A high-density microsatellite consensus map for bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor App Gen. 2004;109:1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Hunger RM, Carver BF, Zhang H, Yan L. Genetic characterization of powdery mildew resistance in U.S. hard winter wheat. Mol Breeding. 2009;24:141–152. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9279-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simkova H, Safar J, Kubalakova M, Suchankova P, Chalkova J, Robert-Quatre H, Azhaguvel P, Weng YQ, Peng JH, Lapitan NLV, Ma YQ, You FM, Luo MC, Bartos J, Dolezel J. BAC libraries from wheat chromosome 7D: Efficient tools for positional cloning of aphid resistance genes. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:302543. doi: 10.1155/2011/302543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krattinger SG, Wicker T, Keller B. In: Genetics and genomics of the Triticeae, plant genetics and genomics: crops and models. Muehlbauer G, Feuillet C, editor. New York: Springer US; 2009. Map-based cloning of genes in Triticeae (wheat and barley) pp. 337–357. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD, Leitch IJ. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Ann Botany. 1995;76:113–176. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1995.1085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel PJ, Ramakrishna W, Bennetzen JL, Busso CS, Dubcovsky J. Transposable elements, genes and recombination in a 215-kb contig from wheat chromosome 5Am. Funct Integr Gen. 2002;2:70–80. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, Yahiaoui N, Guyot R, Schlagenhauf E, Liu Z, Dubcovsky J, Keller B. Rapid genome divergence at orthologous low molecular weight glutenin loci of the A and Am genomes of wheat. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1186–1197. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale MD, Cho S, Sharp PJ. In: Gene manipulation in plant improvement II. Gustafson JP, editor. NY: Plenum Press; 1990. RFLP mapping in wheat-progress and problems; pp. 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset M, Bonnin I, Remoué C, Falque M, Rhoné B, Veyrieras JB, Madur D, Murigneux A, Balfourier F, Le Gouis J, Santoni S, Goldringer I. Deciphering the genetics of flowering time by an association study on candidate genes in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor App Gen. 2011;123:907–926. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1636-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrells ME, La Rota M, Bermudez-Kandianis CE, Greene RA, Kantety R, Munkvold JD, Miftahudin, Mahmoud A, Ma X, Gustafson PJ, Qi L, Echalier B, Gill BS, Matthews DE, Lazo GR, Chao S, Anderson OD, Edwards H, Linkiewicz AM, Dubcovsky J, Akhunov ED, Dvorak J, Zhang D, Nguyen HT, Peng J, Lapitan NL, Gonzalez-Hernandez JL, Anderson JA, Hossain K, Kalavacharla V, Kianian SF. et al. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of wheat and rice genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:1818–1827. doi: 10.1101/gr.1113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Echalier B, Chao S, Lazo GR, Butler GE, Anderson OD, Akhunov ED, Dvorák J, Linkiewicz AM, Ratnasiri A, Dubcovsky J, Bermudez-Kandianis CE, Greene RA, Kantety R, La Rota CM, Munkvold JD, Sorrells SF, Sorrells ME, Dilbirligi M, Sidhu D, Erayman M, Randhawa HS, Sandhu D, Bondareva SN, Gill KS, Mahmoud AA, Ma XF, Miftahudin, Gustafson JP. et al. A chromosome bin map of 16,000 expressed sequence tag loci and distribution of genes among the three genomes of polyploid wheat. Genetics. 2004;168:701–712. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463:763–768. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata N, Moore G, Nagamura Y, Foote T, Yano M. Conservation of genome structure between rice and wheat. Nat Biotechnol. 1994;12:276–278. doi: 10.1038/nbt0394-276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale MD, Devos KM. Comparative genetics in the grasses. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1971–1974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Carver BF, Wang S, Cao S, Yan L. Genetic regulation of developmental phases in winter wheat. Mol Breeding. 2010;26:573–582. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9392-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Carver BF, Zhu X, Fang T, Chen Y, Hunger RM, Yan L. A single-nucleotide polymorphism that accounts for allelic variation in the Lr34 gene and leaf rust reaction in hard winter wheat. Theor App Gen. 2010;121:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T, Campbell KG, Liu Z, Chen X, Wan A, Liu Z, Li S, Cao S, Chen Y, Bowden RL, Carver BF, Yan L. Stripe rust resistance in the wheat cultivar Jagger is due to Yr17 and a novel resistance gene. Crop Sci. 2011;51:2455–2465. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2011.03.0161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. Jasmonate- and salicylate-mediated plant defense responses to insect herbivores, pathogens and parasitic plants. Pest Man Sci. 2009;65:497–503. doi: 10.1002/ps.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Creelman RA, Mullet JE. A chloroplast lipoxygenase is required for wound-induced jasmonic acid accumulation in Arabidopsis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8675–8679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudert D, Pfannschmidt U, Lottspeich F, Hollander-Czytko H, Weiler EW. Cloning, molecular and functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana allene oxide synthase (CYP74), the first enzyme of the octadecanoid pathway to jasmonates. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:323–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00021793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel I, Hause B, Miersch O, Kramell R, Kurz T, Maucher H, Weichert H, Ziegler J, Feussner I, Wasternack C. Jasmonate biosynthesis and the allene oxide cyclase family of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51:895–911. doi: 10.1023/A:1023049319723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stintzi A, Browse J. The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant, opr3, lacks the 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase required for jasmonate synthesis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10625–10630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190264497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassner J, Schaller F, Frick UB, Howe GA, Weiler EW, Amrhein N, Macheroux P, Schaller A. Characterization and cDNA-microarray expression analysis of 12-oxophytodienoate reductases reveals differential roles for octadecanoid biosynthesis in the local versus the systemic wound response. Plant J. 2002;32:585–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reumann S, Ma C, Lemke S, Babujee L. AraPerox. A database of putative Arabidopsis proteins from plant peroxisomes. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2587–2608. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.043695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia N Obtention des bles tendres resistants au pietin-verse par croisements interspecifiques bles x Aegilops Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l‘Académie de l‘Agriculture de France 196753149–154.17597171 [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Ohm HW, Cambron SE, Williams CE. Molecular mapping determines that Hessian fly resistance gene H9 is located on chromosome 1AS of wheat. Plant Breeding. 2005;124:525–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2005.01139.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sears ER. In: Chromosome manipulations and plant genetics. 1. Rilly R, Lewis KR, editor. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd; 1966. Nullisomic–tetrasomic combinations in hexaploid wheat; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yahiaoui N, Brunner S, Keller B. Rapid generation of new powdery mildew resistance genes after wheat domestication. Plant J. 2006;47:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot R, Yahiaoui N, Feuillet C, Keller B. In silico comparative analysis reveals a mosaic conservation of genes within a novel colinear region in wheat chromosome 1AS and rice chromosome 5S. Funct Integr Gen. 2004;4:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachermayr G, Feuillet C, Keller B. Molecular markers for the detection of the wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr10 in diverse genetic backgrounds. Mol Breeding. 1997;3:65–74. doi: 10.1023/A:1009619905909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanini MP, Saltzmann KD, Puthoff DP, Gonzalo M, Ohm HW, Williams CE. A novel wheat gene encoding a putative chitin-binding lectin is associated with resistance against Hessian fly. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8:69–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Echegaray E, Whitworth RJ, Wang H, Sloderbeck PE, Knutson A, Giles KL. Virulence analysis of Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor) populations from Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. J Econ Entomol. 2009;102:774–780. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubcovsky J, Galvez AF, Dvorak J. Comparison of the genetic organization of the early salt stress response gene system in salt-tolerant Lophopyrum elongatum and salt-sensitive wheat. Theor App Gen. 1994;87:957–964. doi: 10.1007/BF00225790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Brown-Guedira GL, Hatchett JH, Owuoche JO, Chen M. Genetic characterization and molecular mapping of a Hessian fly resistance gene (Hdic) transferred from T. turgidum ssp. Dicoccum to common wheat. Theor App Gen. 2005;111:1308–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Carver BF, Wang S, Zhang F, Yan L. Genetic loci associated with stem elongation and winter dormancy release in wheat. Theor App Gen. 2009;118:881–889. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence comparison of TaOPR1-A and TaOPR2-A.

Sequence comparison of a LOX gene between wheat and rice.