Abstract

Fearful temperament is associated with risk for the development of social anxiety disorder in childhood; however, not all fearful children become anxious. Identifying maladaptive trajectories is thus important for clarifying which fearful children are at risk. In an unselected sample of 111 two-year-olds (55% male, 95% Caucasian), Buss (2011) identified a pattern of fearful behavior, dysregulated fear, characterized by high fear in low threat situations. This pattern of behavior predicted parent- and teacher-reported withdrawn/anxious behaviors in preschool and at kindergarten entry. The current study extended original findings and examined whether dysregulated fear predicted observed social wariness with adults and peers, and social anxiety symptoms at age 6. We also examined prosocial adjustment during kindergarten as a moderator of the link between dysregulated fear and social wariness. Consistent with predictions, children with greater dysregulated fear at age 2 were more socially wary of adults and unfamiliar peers in the laboratory, were reported as having more social anxiety symptoms, and were nearly four times more likely to manifest social anxiety symptoms than other children with elevated wariness in kindergarten. Results demonstrated stability in the dysregulated fear profile and increased risk for social anxiety symptom development. Dysregulated fear predicted more social wariness with unfamiliar peers only when children became less prosocial during kindergarten. Findings are discussed in relation to the utility of the dysregulated fear construct for specifying maladaptive trajectories of risk for anxiety disorder development.

Keywords: Social anxiety, kindergarten adjustment, fear dysregulation, context

Among the most common forms of anxiety disorder in childhood and adolescence is Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), with estimates of lifetime prevalence in childhood and adolescence ranging from 6-20% (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006; Merikangas et al., 2010). Fearful temperament (most often studied as behavioral inhibition) is an early vulnerability associated with the development of SAD (Biederman et al., 2001; Biederman et al., 1993; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008; Ollendick & Hirshfeld-Becker, 2002) as well as related constructs like social wariness. However, effect sizes are typically modest and there have been studies that do not find the predicted association (Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008). Thus, identification of which fearful children are most at risk is crucial for progress in the field, and this is the goal of the current study. This study describes a longitudinal follow-up of a previously identified sample of toddlers with a dysregulated fear profile, distinct from behavioral inhibition, that is characterized by high fear in low threat situations (Buss, 2011). In a previous report, we demonstrated that toddlers with this dysregulated profile of fearful behavior were elevated in adult-reported social wariness during preschool and the transition to kindergarten (Buss, 2011). What remains unknown is whether this early identification of risk extends through the kindergarten year and specifically to the development of SAD symptoms. The initial transition to formal schooling is stressful for many children (Rimm-Kaufman & Kagan, 2005), but over the kindergarten year, it is hypothesized that an adaptive adjustment pattern is for children to become less anxious, more prosocial, and more engaged with peers. We do not know, however, whether this is the case for children with a dysregulated fear profile, but expect deviation from the typical pattern because this profile is defined by persistent fearfulness even in benign contexts. Thus, school may represent a new social context that becomes less threatening for most children over the year, but may exacerbate social difficulties for children who are more dysregulated at the outset.

Fearful Temperament a Risk Factor for Development of Anxiety Symptoms

Temperamentally fearful children are characteristically wary and fearful in novel situations, have increased physiological reactivity at rest and during challenge, and develop a pattern of avoidance of novelty (Garcia-Coll, Kagan, & Reznick, 1984; Kagan, Reznick, Clarke, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984). There is diversity in the literature on how fearful temperament is measured (e.g., parent report vs. observation, continuous vs. extreme group) and conceptualized (e.g., shyness in social situations, component of negative affect). However, the bulk of the literature has been framed by the prominent approach of behavioral inhibition. The construct of behavioral inhibition stems from a biological perspective of temperament that suggests that wary and avoidant behavior results from over-reactive fear-emotion circuitry including the amygdala and sympathetic nervous system (Kagan, 1994). Traditionally, fearful temperament is measured early in development from an average of observed toddler fearful behavior during a series of novel episodes (Garcia-Coll et al., 1984), although this can be assessed even earlier by examining infants’ high motor, high negative reactions to stimuli (Kagan & Snidman, 1991; Kagan, Snidman, Kahn, & Towsley, 2007). Fearful temperament is a stable trait (Kagan & Fox, 2006; Kagan et al., 2007), with the highest stability rates observed in children at the extremes (Davidson & Rickman, 1999; Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson, & Rickman, 2002).

Risk for anxiety disorders among temperamentally fearful toddlers and preschoolers, examined in both clinically-referred and community samples, has consistently been found with prevalence ranging between 17-34% (Biederman, Rosenbaum, Hirshfeld, Faraone, & et al., 1990; Hayward, Killen, Kraemer, & Taylor, 1998; Hirshfeld, Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc, & et al., 1992; Rosenbaum, Biederman, Hirshfeld, Bolduc, & et al., 1991), and a particular risk for SAD (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008). In a follow-up of one of the Kagan cohorts, Schwartz and colleagues (Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999) found that inhibited children were less likely to interact spontaneously with an experimenter and more likely to display generalized social anxiety symptoms in adolescence. Evidence is accumulating that it is stable fearfulness across development that is most predictive of SAD symptoms (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Hirshfeld et al., 1992).

Not all studies find this predicted association (Stifter et al., 2008), and the majority of children classified as temperamentally fearful (who are putatively at risk for internalizing disorders) never develop symptoms. This could be due to the lack of stability in fearful behavior across development. For instance, Prior and colleagues (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000) found that children who are inhibited in toddlerhood but not later in childhood are less likely to develop anxiety symptoms. Indeed, research supports the idea that many children naturally develop out of this temperamental profile (Côté, Tremblay, Nagin, Zoccolillo, & Vitaro, 2002). Another possible explanation for the lack of prediction to anxiety symptoms is that particular experiences with parents and other caregivers (e.g., in child care settings) may influence movement away from the extremes (Arcus, 2001; Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001). Still another possibility is that the children identified as fearful are not a homogeneous group and therefore the trajectories should not be expected to be the same for all children in this “group”. The ability to characterize a risk profile early in development (e.g., in toddlerhood) will be valuable for targeted programs of prevention and intervention aimed at normalizing trajectories of early risk. Thus, the ultimate goal for this area of research is to identify which type of fearful child is most at risk, and to understand why.

Traditional observational approaches to fearful temperament characterize children as high in fear using averages of behavior across highly novel and objectively threatening situations (Garcia-Coll et al., 1984; Goldsmith & Campos, 1990). But, it is not maladaptive for children to exhibit fear in highly novel, threatening situations. This insight alone may explain why most “high-fear” children do not develop SAD symptoms. Measuring fearful behavior across a broad range of eliciting contexts (including benign situations) provides a solution (Buss, 2011; Buss, Davidson, Kalin, & Goldsmith, 2004). In this approach, the changing pattern of fear that toddlers display as situations increase in threat is of interest, rather than the average of fearful behavior across the situations. A dysregulated pattern of fearful behavior (characterized by high fear in benign or low threat situations) was associated with elevated adult report of social wariness and anxious behaviors in preschool and during the fall transition to kindergarten (Buss, 2011). Moreover, dysregulated fear predicted anxious behavior even after controlling for toddler inhibition (an average measure of fear behavior across situations) demonstrating the uniqueness of this approach and suggesting a more homogeneous profile of risk for anxiety symptoms. The present study used a multi-method approach to determine whether dysregulated fear conferred risk for social wariness (e.g., peer withdrawal) during kindergarten and SAD symptoms after the kindergarten year.

Adjustment to Kindergarten for Fearful Children

It has also been shown that temperamentally fearful children may show failures in adaptation at important developmental milestones (e.g., school transition) that would lead to later disorder as would be suggested by developmental psychopathology theory (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). For example, temperamentally fearful children are likely to exhibit withdrawal in social situations (Kagan et al., 1984; Rubin, Burgess, & Coplan, 2002; Rubin & Lollis, 1988), and lack competence with peers (LeMare & Rubin, 1987; Rubin, Daniels-Beirness, & Bream, 1984), which may interfere with the formation of friendships and lead to peer rejection (Nelson, Rubin, & Fox, 2005; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009; Rubin et al., 1984). These social vulnerabilities may put fearful children at increased risk for later SAD and other internalizing symptoms.

The transition to formal schooling, in particular, represents a salient developmental milestone (Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Coplan & Arbeau, 2008), wherein children face new classroom demands, larger schools, and an increasingly large social network separate from the family context. Although this transition may be stressful for many children and a period of adaptation is expected, fearful children have heightened difficulty. For instance, fearful temperament (Buss, 2011; Early et al., 2002; Rimm-Kaufman & Kagan, 2005) predicts children's social wariness and avoidance during the initial transition to kindergarten. In addition, this poor initial transition may set up a pattern of behavior that will extend through the school-year resulting in increasing problems. Initial social wariness may subsequently prevent fearful children from capitalizing on the resources and opportunities in the environment that will help with adjustment (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002).

Social Adjustment and Competence in Fearful Children

Given the hypothesized association between fearful temperament and social anxiety symptoms summarized above, young children's social behavior with peers is important to examine as a significant component or moderator of the trajectory from fearful behavior to anxiety symptom development. As mentioned previously, fearful behavior puts the child at risk for failure to adapt to new situations, such as the new peer environment, in elementary school (Rimm-Kaufman & Kagan, 2005). A large body of work has demonstrated a consistent prediction from fearful temperament to later wariness with unfamiliar peers (Degnan, Henderson, Fox, & Rubin, 2008; Fox et al., 2001; Henderson, Marshall, Fox, & Rubin, 2004; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002). This type of social wariness is characterized by frequent onlooking and hovering behavior, being unoccupied in social company, verbal inhibition, and retreat from social overtures from peers (Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & et al., 1994; Rubin, Burgess, & Coplan, 2002; Rubin, Burgess, Kennedy, & Stewart, 2003). This type of social wariness interferes with the development of adequate social skills, leading to negative self-perceptions and lower self-esteem (Rubin et al., 2003), likely because children who avoid peer interactions have fewer opportunities to practice adaptive social skills. Socially wary children have also been found to display anxious behaviors (Coplan et al., 1994) and other internalizing symptoms (Henderson et al., 2004). Thus, fearful children may be at particular risk because of difficulty with peer interactions (Coie & Cillessen, 1993; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Hymel, Rubin, Rowden, & LeMare, 1990; Kochanska & Radke-Yarrow, 1992; Olson & Rosenblum, 1998; Rubin & Mills, 1988), and temperamentally fearful toddlers who are more socially withdrawn have a higher risk of developing anxious behavior (Degnan & Fox, 2007).

On the other hand, positive peer relationships are important for preventing anxiety symptoms in temperamentally fearful children (Degnan & Fox, 2007). In a study examining multiple risk factors for the development of anxiety, Bosquet and Egeland (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006) reported that low social competence (peer sociability, peer acceptance, and leadership qualities) in middle childhood was associated with the development of anxiety in adolescence. Specifically, children who were at risk in infancy and toddlerhood showed more anxious symptoms in adolescence if they were low in social competence in middle childhood. One component of social competence that has received a great deal of attention in the peer literature is prosocial behavior. The development of prosocial skills may be particularly important for children who are at risk for anxiety. Children are often characterized as prosocial if they are friendly and inclusive, initiate social interaction, engage in positive play with others (Greener & Crick, 1999), or act in ways that promote others’ well-being (Hastings, Utendale, & Sullivan, 2007). Children with more anxious and fearful tendencies display fewer prosocial behaviors (Duchesne, Larose, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2010; Ladd & Profilet, 1996; Stanhope, Bell, & Parker-Cohen, 1987). In a recent study examining trajectories of anxiety from kindergarten to 6th grade, Duchesne and colleagues found that children in a high-stable anxiety trajectory group and low-increasing anxiety trajectory group were significantly less likely to display prosocial behavior compared to a low-stable anxious trajectory group (Duchesne et al., 2010). However, some work reports no association between fearfulness and prosociality (Diener & Kim, 2004; Young, Fox, & Zahn-Waxler, 1999) or vast individual differences in prosocial behaviors among anxious children (Gazelle, 2008). These inconsistent findings suggest that prosocial behavior may therefore best be conceptualized as a moderator of the association between early temperamental fearfulness and later anxiety symptoms. Thus, the development of prosocial skills may buffer temperamentally fearful children against maladaptive outcomes.

The Current Study

Our previous work has illustrated that dysregulated fear in toddlerhood predicts anxiety and internalizing outcomes during early childhood and when children begin kindergarten (Buss, 2011). The current investigation was designed to expand these findings by investigating in the same sample whether this vulnerability (fear dysregulation) predicted social wariness during the kindergarten year, and to explore the role of social adjustment in this aspect of development. Multiple assessments of behavioral and adult-reported social functioning were included in this study. Social wariness in the fall of the kindergarten year was assessed by observations of fearful behavior in a laboratory visit. Over the course of the school year, social adjustment was assessed in two ways: observations of behavior in an unfamiliar peer free play context during the spring of the school year and teacher-reported prosocial behavior in the fall and spring. Social anxiety was measured via parent-report of symptoms on a diagnostic interview in the summer after kindergarten.

This investigation had three primary predictions. First, we hypothesized that children's dysregulated fear would predict kindergarten outcomes related to social competence. Second, based on the literature reviewed above, prosocial behavior was expected to be a key aspect of social adjustment that would moderate the development of socially wary behavior during kindergarten. Third, we expected social anxiety disorder symptoms identified after the kindergarten year to be more prevalent among children who showed more fear dysregulation at 24 months relative to a group of children who were identified as more fearful than average children, but who were not dysregulated.

Method

Participants

One hundred and eleven 2-year-olds (M = 24.05 months; 55% male) and their caregivers were recruited from a small, Midwestern city and surrounding rural community into a longitudinal study using a database of public birth announcements that indicated date of birth, gender, weight, and parents’ names. Birth weight under 5.5 lbs. was an exclusionary criterion. Families with children who were approaching 24-months of age were identified from this database and mailed letters and postcards to return if interested in the study. When families returned postcards they were contacted by phone to schedule a laboratory visit which took place after the child's second birthday. Immediately following this, we mailed families consent forms and questionnaires to complete prior to their laboratory visit. This sample was predominantly middle-class (annual family income ranged from less than $20,000 (3%) to above $61,000 (52%); and highly educated, 63% of fathers and 61% of mothers had a 4-year college degree or less and the lowest was 10th grade and 12th grade, respectively. Children's race/ethnicity was reported as predominantly non-Hispanic, European American (95.3%), African-American (1.2%), Hispanic (1.2%), Asian-American (1.2%), or was not specified (1.2%). The majority of children were from intact families (5.9% divorced or single parent families by the time children began kindergarten).

Approximately 1 month before children entered kindergarten (Mage = 5.9 years, SDage = 0.33 years), families were invited back to the laboratory to participate in a series of assessments. Twenty-six families did not participate: 11 declined, 15 were unreachable. Eighty-five children (57.6% boys) and their families participated in at least one of the kindergarten assessments and are the focus of the current investigation. Data from four assessments during the kindergarten year will be presented in the current study: (1) an individual laboratory visit in the fall (89% of the kindergarten sample participated; Mage = 5.88 years, SDage = 0.33 years), (2) fall and spring teacher-reported questionnaire packets (4 children were homeschooled so did not have teacher report-data; 68% of the 81 eligible teachers participated), (3) a peer group laboratory visit in the spring (85% participation; Mage = 6.13 years, SDage = 0.31 years), and (4) parent-reported clinical symptoms of social anxiety in the summer after kindergarten (60% selected for participation; Mage = 6.57 years, SDage = 0.49 years).

Procedures and Measures

Children were followed from age 24 months until the summer after their kindergarten year in a prospective investigation of emotion and temperament development. The current study used data from one assessment at 2 years and four assessments during the kindergarten year. Parents provided written consent for their own and their children's participation at each assessment, and teachers provided written consent for their participation in fall and spring. The initial 24-month laboratory visit will be described briefly in the next section (for a more detailed description of each laboratory procedure and micro-coding procedures see (Buss, 2011; Kiel & Buss, 2010). Families and teachers received a modest honorarium for their participation in each assessment and children selected a small prize at the end of the visits.

Dysregulated fear at age 2 individual laboratory visit

With mothers present, children participated in a series of novel laboratory episodes from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB) (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000; Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996), designed to elicit fear and wariness in contexts that ranged from low to high threat. Because of specific hypotheses regarding the threat level of the episodes, children were assigned to one of four counterbalanced episode orders fully described in a previous report (Buss, 2011). Contexts included two episodes that were designed to be the most engaging and least threatening and (an interaction with a clown and a puppet show), two that were moderately engaging and moderately threatening (a male stranger approach and a stranger working episode), and two that were least engaging and most threatening (a mechanized spider and a remote-controlled robot). The Clown and Puppet Show episodes (low threat, high engaging) each lasted approximately 3 minutes. In these episodes, two friendly puppets (manipulated by an experimenter hidden behind a puppet show theater) or a friendly unfamiliar female experimenter dressed as a clown invited toddlers to play with a series of toys or take part in brief games (e.g., blowing bubbles with the clown, playing with a fishing pole with the puppets). It is important to note that the Clown episode differs from other “clown” procedures in the literature (Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002) because the clown in the current was friendly and engaging. The Stranger Approach and Stranger Working episodes (moderate threat, moderately engaging) each lasted approximately 2 minutes. In the former, an unfamiliar male experimenter entered the room and attempted to engage the child in conversation (e.g., “Are you having fun playing here today?”) while moving toward the child, eventually sitting down within 2 feet of the participant. In the latter, an unfamiliar female experimenter entered the room holding a clipboard, walked to a desk at the far end of the room, and pretended to “work.” She only interacted with the child if the child initiated conversation or approached, saying, “I’m just going to work here while you play.” The Spider and Robot episodes (designed to be high threat, least engaging) each lasted approximately one minute. In Spider, the child sat opposite a large fuzzy spider mounted on a remote-controlled vehicle. An unseen experimenter in a control room manipulated the spider so that it moved toward the child's chair, stopped in the middle of the room, retreated, and then moved toward the child a second time, coming all the way up to the chair. In Robot, children sat facing a platform on which a remote-controlled toy robot was displayed. An unseen experimenter in the control room manipulated the robot so it moved around the platform, making noises and lighting up. After each of these episodes, the experimenter entered the room and invited the child to examine and touch the stimuli.

Fear coding

Behavior in each of the 6 novel episodes was reliably (κ > .65 and percent agreement above 80% coded on 15% of cases) micro-coded on a second-by-second basis for a wide range of activities and behaviors; of interest in the present investigation were fearful behaviors including facial fear, bodily fear, freezing, and time spent in proximity to caregiver. Facial fear was coded using the AFFEX system which differentiates emotion expressions based on three regions of the face (Izard, Dougherty, & Hembree, 1983). Fear was coded when brows were straight and raised, or tense, eyes were open wide, and mouth open with corners pulled back. Bodily expressions of fear were indicated when play was diminished, children froze or decreased activity suddenly, and/or when muscles appeared tensed or trembling. Freezing behavior was also scored when children remained still or rigid for two or more seconds. Proximity to caregiver was scored when child was within one arms-length reach of caregiver. A full description of analytic procedures to determine the threat and engagement ordering can also be found in Buss (2011). Following an exploratory Principal Components Analysis (PCA) for each episode, variables representing the duration or timing of each behavior (i.e., duration of facial fear, bodily fear and freezing, time spent in proximity to caregiver, and latency to freeze) were combined into a fear composite, accounting for approximately 25% of the variance. This variable indexed the proportion of time children engaged in fear behaviors during the episode. ICC for the composites ranged from .61 to .73.

Dysregulated fear calculation

Average fear composite scores supported the prediction that episodes differed in putative threat (Buss, 2011) with the high threat tasks (i.e., Spider and Robot) eliciting higher fear scores (M = 37.79, SD = 17.48) than the low threat tasks (i.e., Clown and Puppet Show), which elicited the lowest amount of fear (M = 23.49, SD = 22.92). As described in a previous report, the amount of fear children displayed differed between episode types in line with expectations (see Buss, 2011 for all comparisons). Even more support for the ordering of episodes comes from the proportion of the toddlers who showed any fear behavior during the different types of episodes (< 45%, 50-60%, > 80% for low, moderate and high threat episodes, respectively; (Buss, 2011). The ordering of episodes from low to high threat has also been replicated using a second sample from our laboratory (Kiel & Buss, 2012). Based on the increasing threat that characterized the 6 episodes (Buss, 2011), children were generally expected to show the least fear behavior in the Clown and Puppet Show episodes, more in the Stranger Approach and Stranger Working episodes, and the most intense and prolonged fearfulness to the Spider and Robot episodes. In contrast, children were thought to exhibit dysregulated fear when they were unable to match their fearful response to the incentive properties of the eliciting stimuli as determined by the threat level of each episode (e.g., a child who shows extreme fearfulness in response to the low threat Puppet Show episode). Thus, dysregulated fear represents a failure to appropriately calibrate fear behavior to the characteristics of the eliciting context. In order to characterize the pattern of fearful behavior across episodes, multilevel modeling (MLM) (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used to create a continuous measure of fear across the 6 episodes for each child. Each child's fear was represented by a continuous slope coefficient and extracted as Empirical Bayesian (EB) estimates and added to the mean estimate (Buss, 2011). The mean intercept was 20.9, and the mean slope value was 14.37 (SD = 5.55; range: -3.31 to 25.04). For each increase in threat level, the average amount of time children displayed fear increased by 14% (e.g., a child showing fear 20% of the time in Puppet Show would show fear approximately 34% of the time in Stranger Approach). Higher or more positive slope values on this continuous measure thus indicate context-appropriate fear regulation, whereas lower or more negative slopes indicate greater dysregulation.

Kindergarten individual visit

. During the kindergarten year, children returned to the laboratory for a visit composed of episodes similar to those they participated in as toddlers but modified for older children. The Scary Mask episode was designed to elicit fear in a high threat social context. An unfamiliar female experimenter wearing a Halloween-style mask and a hooded sweatshirt introduced herself to the child and, after 15 seconds, removed the mask, explained that it was a costume, and invited the child to touch it and try it on. The Stranger Approach episode was designed to elicit fear in a lower-threat social context. A friendly adult male entered a room where the child was seated, alone, and attempted to engage the child in conversation for one minute (e.g., “Have you been here before?”, “Are you having a good time here today?”). Children's behaviors during these episodes were reliably micro-coded on a second-by-second basis (percent-agreement = 86%-96%; κ = .72 - .86), and a composite of fearfulness was created for each episode: latency to freeze (reverse scored), duration of facial fear, bodily fear, and freezing. The composite for Stranger Approach was slightly skewed, and so was square root transformed prior to data analysis (before transformation, skewness = 1.66, SE skew = .26; after transform skew = .671, SE skew = .26).

Unfamiliar peer visit

In the spring of kindergarten, children returned to the lab for a peer group visit. Children were observed with two or three unfamiliar, same-aged, same-gendered peers in a 15-minute unstructured free play where toys (e.g., board games, jump ropes, hula hoops) were available. The Play Observation Scale was used to code play behavior (Rubin, 2001). We examined reticent (unoccupied, onlooking) and anxious behaviors. Unoccupied behaviors included staring blankly or wandering without apparent purpose. Onlooking behaviors included watching other children without joining in their activity. Anxious behaviors included crying, fidgeting (e.g., hair twisting, nail biting), and appearing nervous. Additional coding of children's fear and wariness scored each minute on a 1-5 point scale to supplement this scoring. Reliability for reticent and anxious behaviors was calculated on approximately 10% of cases and found to be adequate (reticent behavior percent-agreement = 93%; κ = .61; anxious behavior ICC = .93). Reliability for fear and wariness codes was also good (percent-agreement = 98% and κ = .79). Proportion of anxious behaviors, reticent behavior, and children's average fear/wariness during the peer free play were standardized and aggregated to form a composite variable of social wariness.

Adult-reported prosocial behavior and anxiety symptoms

In the fall and spring of kindergarten, teachers completed the MacArthur Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ)(Armstrong & Goldstein, 2003; Essex et al., 2002) to assess a variety of behaviors that index adjustment (e.g., prosocial behavior) or maladjustment (e.g., internalizing symptoms). Teachers responded to all items on the HBQ using a three-point scale (from never/infrequently exhibited to frequently/highly characteristic). We used the Prosocial Behavior scale for these analyses (20 items) (α = .94, in both the fall and spring). Example items from this scale include: “will try to help someone who has been hurt,” “can work easily in a small group,” and “shares candies and extra food.”

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) Child Version (Silverman & Albano, 1996) was administered to parents of a subset of children (n = 51) in the summer after the kindergarten year when children were at least 6 years old. Blind to age 2 dysregulated fear scores and age 2 behavior, children were selected for this assessment if they met at least one criterion suggesting increased risk for anxiety symptoms: above average (> 1 SD) globally-coded (i.e., single score on a 5-point scale for each episode) negative affect or shyness behavior averaged across the individual laboratory tasks at age 5, or above average (>1 SD) parent report of anxiety symptoms or peer social withdrawal on the HBQ in the fall of the kindergarten year (Buss, 2011). Although dysregulated fear status was not considered in this selection, follow-up exploration of descriptive data revealed that all of the children whose fear slopes were below the mean (i.e., indicating greater dysregulation) (Buss, 2011) were included in the larger group that had ADIS interviews. Interviewers were clinical psychology graduate students who established training reliability on administering and scoring the interview with a Ph.D. level clinical psychologist (κ = .80, averaged across symptoms and diagnostic categories). Interviews were double scored on 10% of cases and reliability was high (κ = .97). The Social Anxiety Disorder (i.e., Social Phobia) scale symptom count was used in analyses. Symptom items include endorsement of distress and avoidance of various social situations such as answering or talking on telephone, using public restrooms, attending meetings, and asking teacher for help. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale symptom count was also used in analyses and included items endorsing worry about different situations (e.g., being on time, natural disasters, homework).

Results

We have organized the results into five sections. First, preliminary analyses addressing study attrition, gender differences, and handling of missing data are presented. Second, we describe the steps taken for data reduction. The following three sections address each study hypothesis in turn: The relation of dysregulated fear to social competence in kindergarten, the moderating role of prosocial adjustment during the year, and prediction of social anxiety disorder (SAD) symptoms after the kindergarten year.

Preliminary Analyses

Gender differences

Potential gender differences in observed behavior (in the individual and peer visits) and in adult-reports of behavior were investigated using independent t-tests. No differences emerged on any of these outcomes and our research questions did not focus on gender differences, ts < 1.53, ns. This variable was not considered further.

Study attrition

We compared families who dropped out of the study to those who remained enrolled on key study variables from the age 2 lab visit (i.e., SES, observed fear, and dysregulated fear), and found no significant differences on any variable, ts < 1.20, ns.

Analysis of missing data

Because using listwise deletion to exclude participants without complete data is problematic (i.e., it has been shown to bias parameter estimates and unnecessarily limit power; (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Widaman, 2006), we chose to impute missing kindergarten data for only the 85 children who participated in at least one of the assessments. Of note, we did not impute teacher-report data for four children who were homeschooled, and we did not impute ADIS data for children who were not selected for inclusion in the clinical interview assessment. The Missing Value Analysis in SPSS suggested that data were not missing completely at random (Little's MCAR χ2 (138) = 167.62, p = .044). A t-test comparing age 2 dysregulated fear scores of children who were included in this study and children who were not included because they did not have any kindergarten assessments showed there was no difference on this variable (our key predictor), t(110) = 0.87, ns. We therefore imputed missing data for the kindergarten year observations and teacher-reports using the expectation/maximization (EM) algorithm because this method has been recommended for longitudinal analyses over other methods like mean substitution or listwise deletion (Howell, 2007; Jeličić, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009). This algorithm provides a maximum likelihood (ML) estimation of the covariance matrix, produces reliable estimates in simulation studies with comparable sample sizes and a similar pattern of missingness (non-MCAR data), has been highly recommended over other methods that would decrease power to detect effects (Peugh & Enders, 2004; Schafer & Graham, 2002), and this approach was used in our previous investigation (Buss, 2011).

Prosocial Adjustment During Kindergarten

On average, children showed improvement in prosocial adjustment across the year, according to teacher reports. Children became more prosocial over the course of the year, t(80) = 6.08, p < .0001, d = 1.36 (Fall M = 1.29, SE = 0.04; Spring M = 1.46, SE = 0.04). Four homeschooled children were excluded from this analysis. Although the normative pattern from fall to spring of kindergarten was for children to become more prosocial, some children changed very little, and some children became less prosocial over the year.

Does Dysregulated Fear Predict Social Competence in Kindergarten?

As predicted, dysregulated fear was associated with multiple social adjustment outcomes across the kindergarten year including observed behavior and parent report of anxiety symptoms (Table 1). Greater dysregulated fear at age 2 (i.e., a flatter or more negative slope) was associated with greater observed fear behavior in the less-threatening Stranger Approach, but was not associated with fear in the high threat Scary Mask. Thus, the dysregulated fear measure showed specificity in predicting children's later fear only in a low threat social context. Greater dysregulated fear at age 2 was also associated with more observed social wariness in the unfamiliar peer free play context.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for study variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dysregulated fear (Age 2) | 14.37 (5.55) | ||||||

| Teacher Report (Age 5-6) | |||||||

| 2. Fall Prosocial Behavior | 1.29 (0.40) | 0.01 | |||||

| 3. Spring Prosocial Behavior | 1.46 (0.39) | 0.06 | 0.80*** | ||||

| Observed Behavior (Age 5-6) | |||||||

| 4. Fear in Stranger Approach | 16.96 (21.51) | -0.21* | 0.27* | 0.19+ | |||

| 5. Fear in Scary Mask | 25.10 (19.57) | -0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.24* | ||

| 6. Social Wariness in Unfamiliar Peer Free Play | 0.04 (2.35) | -0.29** | -0.03 | -0.12 | 0.23* | 0.16 | |

| Parent Report (n = 51; Age 6) | |||||||

| 7. SAD Symptoms on ADIS | 3.02 (2.95) | -0.29* | -0.12 | -0.14 | -0.07 | 0.24* | 0.19 |

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

ADIS = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder. Raw values are presented in the table, but square-root transformed values were used in analyses for fear in Stranger Approach.. Fear in Stranger Approach and Scary Mask is percent of episode child engaged in fearful behaviors. Fear in unfamiliar peer free play is an aggregate of anxious and reticent behaviors and fearfulness. Positive scores on dysregulated fear variable indicate better regulation.

Does Prosocial Adjustment Moderate the Relation between Dysregulated Fear and Social Wariness?

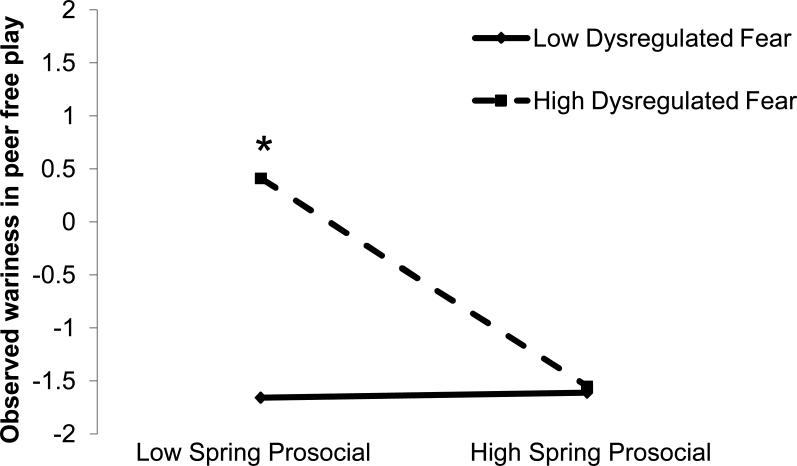

Next we investigated the role of teacher-reported prosociality in moderating the relation between dysregulated fear and observed social wariness in the unfamiliar peer free play. The four homeschooled children were also excluded from this analysis. We tested the main and interactive effects of prosocial adjustment and dysregulated fear predicting social wariness during the age 5 Peer Free Play. Variables were mean-centered prior to analyses. In the first step of the model, parent-report of fall prosocial adjustment was entered as a covariate. In Step 2 we entered age 2 dysregulated fear and the spring prosocial adjustment. In Step 3, we entered the interaction term between (dysregulated fear and spring prosocial adjustment). Summary statistics are presented in Table 2. Fall prosocial adjustment was not a significant covariate. We found a main effect of dysregulated fear such that children with greater dysregulated fear showed more social wariness during the peer visit, but this was subsumed by a significant interaction of dysregulated fear and spring prosocial adjustment in Step 3 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Regression Predicting Social Wariness in Unfamiliar Peer Free Play

| ΔR2 | ΔF | β | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. | 0.001 | 0.09 | |||

| Fall Prosocial | -0.03 | -0.30 | |||

| Step 2. | 0.11 | 4.84** | |||

| Dysregulated fear | -0.30 | -2.75** | |||

| Spring Prosocial | -0.12 | -1.15 | |||

| Step 3. | 0.07 | 5.98* | |||

| Dysregulated fear X Spring Prosocial | 0.27 | 2.45** | |||

Note

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 1.

Interaction of age 2 dysregulated fear and spring prosocial adjustment predicting social wariness in unfamiliar peer free play. Low and high levels correspond to +/- 1SD from mean. Simple slopes testing at low and high levels of Dysregulated Fear showed a relation between spring prosocial and observed wariness only for children with more dysregulated fear.

* p < .05

We probed this interaction by calculating simple slopes for prosocial adjustment at low and high levels of dysregulated fear (+/- 1 SD). For children with low levels of dysregulated fear (better regulation), spring prosocial adjustment did not relate to observed wariness with peers, β = 0.01, t = .03, n.s. In contrast, children with greater dysregulated fear showed more social wariness when playing with unfamiliar peers as spring prosocial adjustment decreased, β = -0.41, t = 2.12, p = .037

Does Dysregulated Fear Predict SAD Symptoms after Kindergarten?

We conducted ADIS interviews with mothers of approximately 60% of the sample. Only children whose kindergarten year assessments suggested that they were more fearful than average were included, because we were specifically interested in whether children with greater dysregulated fear at age 2 would show more symptoms of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) after kindergarten (age 5-6) than children we identified as fearful but not necessarily dysregulated. This allowed us to conduct a conservative test of the predictive utility of dysregulated fear within a sample of children identified as fearful during the kindergarten year.

Most children had four or fewer symptoms (72.5%) and seven children met diagnostic criteria for the disorder (six of these children were identified as high in dysregulated fear). Note, however, that the distribution of number of symptoms was normal so the total number of SAD symptoms parents endorsed (Range: 0 - 11 symptoms) was entered as the dependent variable in a linear regression. Dysregulated fear (M = 13.6, SD = 6.13 for this subsample) significantly predicted SAD symptoms, such that more dysregulation at age 2 was associated with a greater number of symptoms at age 5, β = -.29, t =-2.16, p = .036. To determine whether the relation between dysregulated fear and anxiety was specific to SAD symptoms, we examined generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) symptoms. On average children had fewer GAD symptoms (M = 1.47, SE = 0.26, Range = 0-7) than SAD symptoms (M = 3.02, SE = 0.41, Range = 0-11), t(50) = 4.11, p < .001, d = 1.16. Although there are more possible symptoms that can be endorsed for SAD compared to GAD, it is noteworthy that dysregulated fear did not predict GAD symptoms, β = 0.03, n.s.

To examine the relation between dysregulated fear and SAD symptoms more closely, we split the sample evenly into two groups of children (more dysregulated versus less dysregulated) at the median of the dysregulated fear measure (median = 14.85). We split at the median rather than on direction of slope because dysregulated fear scores at or slightly above zero do not necessarily indicate that children are “well-regulated.” Instead, the two groups created in this split represent children with lower and higher levels of dysregulated fear, rather than groups representing “dysregulated” versus “well-regulated” children. Because most children presented with fewer than four symptoms, we explored whether dysregulated fear was distinctly associated with a lower (four or fewer) versus higher (more than four) number of symptoms in a logistic regression. The model was significant, χ2(1) = 3.99, p = .046, indicating that children who were more highly dysregulated at age 2 were more likely to have a high number of SAD symptoms than children who were less dysregulated. In fact, the odds of having more than four social anxiety symptoms were 3.67 times higher for children with higher dysregulated fear at age 2 (O.R. = 3.67, 95% CI: 0.97 to 13.90). Thus, even within a subsample of fearful children, those with greater dysregulated fear at age 2 were more likely to have SAD symptoms at age 6 than children who were not dysregulated at age 2.

Discussion

We previously showed that dysregulated fear in toddlerhood predicted social withdrawal and anxious behaviors as reported by mothers during preschool and by both mothers and teachers when children transitioned to kindergarten (Buss, 2011). In this original report, there was evidence for the unique contribution of the dysregulated fear profile to the prediction of anxious outcomes compared to a more traditional fearful temperament measure (i.e., behavioral inhibition). The current investigation expanded these findings in a longitudinal follow-up of the participants by demonstrating that dysregulated fear in toddlerhood robustly predicted social wariness and SAD symptoms outcomes throughout the kindergarten year.

We found an association between dysregulated fear in toddlerhood and displays of fear during a low threat, friendly stranger interaction at age 5. Notably, we did not find the same association to a social but higher-threat interaction. This suggests that the low threat interaction with a strange adult evoked context-inappropriate fear for children who were more dysregulated in their fear responses three years earlier. This result suggests longitudinal stability of the key aspect of the dysregulated fear profile identified by our previous work: high fear in low threat situations (Buss, 2011). Stability of individual differences across development is a key defining feature of temperament broadly (Rothbart & Bates, 2006) and fearful temperament specifically (Kagan & Fox, 2006; Kagan et al., 2007). Dysregulated fear also predicted anxious behavior in a free play with unfamiliar children. Thus, the association between dysregulated fear and social wariness is not limited to interactions with unfamiliar adults, but includes children's social behavior with unfamiliar same-aged, same-sex peers. Fearful behavior with peers is one criteria of SAD and is consistent with the extant literature (Coplan et al., 1994; Henderson et al., 2004; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008).

We found that dysregulated fear and prosocial behavior interacted to predict peer wariness. Children showed the most wariness with peers when dysregulated fear was high and spring prosocial behavior was low. Starting the school year with lower prosocial tendencies or having difficulty adapting to a new classroom has been shown to predict later social problems (Coplan & Arbeau, 2008; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002), but the current study is among the first to examine children's prosocial adjustment across the year. Fall prosocial behavior was not a significant predictor of peer wariness, but spring prosocial behavior predicted wariness for dysregulated fear children. Our results suggest that adaptive prosocial behaviors during kindergarten may be protective for temperamentally fearful children's peer relationships. Positive peer relationships have been identified as one path to preventing anxiety in fearful children (Degnan & Fox, 2007). Thus, increasing social competence may buffer against later social problems (Arbeau, Coplan, & Weeks, 2010). This finding demonstrates the importance of examining multiple aspects of children's social milieu to fully characterize the development of social problems.

Conversely, these findings suggest that a lack of social competence with peers in kindergarten is an important component of the development of anxiety for fearful children. Because temperamentally fearful children begin the kindergarten year socially wary (Buss, 2011), they may avoid the very opportunities for peer interaction and affiliation that would help promote normative social adjustment (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002). For instance, it may be difficult for fearful children to engage in prosocial behavior due to distress and avoidance of social situations. It is also possible that these fearful kindergarteners may be reluctant to make use of other resources in the school context, including opportunities for learning (e.g., hesitating to answer a teacher's question or participate in classroom activities, because of unwanted social attention). This lack of engagement with opportunities in the classroom may impact the long-term adjustment outcomes of fearful children as well as maintain their trajectory toward anxiety development. Empirical support for this idea comes from work by Bosquet and Egeland that included a measure of competence, assessing children's ability to engage and enjoy classroom activities and opportunities (both social and academic)(Bosquet & Egeland, 2006). This measure along with social competence more broadly was associated with the trajectory toward anxiety development in adolescence. Our results are consistent with this framework, as we found strong relations between dysregulated fear and later wariness in social contexts. Children with a more dysregulated fear profile at age 2 were found to be more wary of an adult stranger (i.e., low threat social context) and more wary with unfamiliar peers in the laboratory.

Although we did not directly measure quality of peer relationships, other work shows that socially withdrawn children are at risk for developing maladaptive peer relationships (LeMare & Rubin, 1987; Nelson et al., 2005; Rubin et al., 1984; Rubin & Stewart, 1996), experiencing lower peer acceptance (Hymel et al., 1990), and being rejected and excluded by their peers (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). As has been suggested in the child anxiety literature, limited interactions (in both frequency and quality) with peers may reinforce and encourage anxious children's avoidance of subsequent interactions, increasing the risk for anxiety development in later childhood (Rapee, 2001; Vasey & Dadds, 2001). Future studies will test whether children who exhibit dysregulated fear in toddlerhood manifest later anxiety because of the reinforcing nature of their wariness in social interactions in multiple contexts across development. In sum, the moderation described here highlights the importance of developing social competence during kindergarten for more at-risk fearful children. Positive social experiences and behavior during middle childhood are critical for ensuring adaptive trajectories for fearful children (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006) because fear-related risk for SAD extends well beyond childhood (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008).

Finally, we examined clinical symptoms of Social Anxiety Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder using the ADIS parent interview at the end of kindergarten. The subsample of children whose parents were asked to participate in these interviews was selected because assessments at age 5 strongly suggested that they were more fearful than average children. Even within this putatively homogeneous group of highly fearful children, we found specific relations between dysregulated fear at age 2 and SAD symptoms. Dysregulated fear predicted a greater number of SAD anxious symptoms, and strikingly, we found that children with greater levels of dysregulated fear had higher odds (nearly 4 times) of manifesting a high number of SAD symptoms. The magnitude of this effect is consistent with recent research examining the lifetime prevalence of social anxiety symptoms among adolescents who were stably behaviorally inhibited from toddlerhood to childhood (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009). Our finding illustrates the validity of dysregulated fear in identifying children who are at elevated risk for manifesting SAD symptoms in childhood and is consistent with the emerging literature that fearful temperament is associated with SAD specifically (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008). Further evidence of this specificity: we did not find that dysregulated fear predicted increased GAD symptoms relative to other fearful/wary children. However, one possible reason is that GAD symptoms are only beginning to emerge in children this young and, in fact, GAD symptom levels were relatively low compared to SAD. We would speculate that as GAD symptoms increase through late childhood and adolescents, dysregulated fear would also predict increased GAD symptoms. Furthermore, as has been suggested increased SAD symptoms across childhood could increase the chances for GAD symptom development (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008).

Why might dysregulated fear predict anxiety symptoms? One explanation is that the experience of fear in relatively low threat situations results in negative social experiences, which reinforce children's perceptions of low threat situations as threatening. The lack of understanding of explanatory mechanisms and processes through which anxiety develops in children is a salient conceptual obstacle to progress in this field. Consistent across developmental etiological models of anxiety is the notion of multi-determinism and the need to integrate across multiple risk and protective factors in order to identify diverse pathways to anxiety development (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Vasey & Dadds, 2001). The risk factors for the development of anxiety in childhood and adolescence include fearful temperament, exposure to community violence, exposure to abuse or experiences of trauma by children or their family members, parental psychopathology, parental overcontrol, and disruptions in the attachment relationship (Egger & Angold, 2006). Although the previous report (Buss, 2011) and the current study focused only on one factor, fearful temperament, we argue that we have expanded understanding of this particular factor that puts children at risk for the development of anxiety by identifying a pattern of changes in fearful behavior that suggests a more specific way to identify at-risk fearful toddlers. We have shown that the risk for later anxiety problems is not, as has been suggested by other models of fearful temperament, simply how much fear children experience or express, but how that fear is regulated or expressed across different situations (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2004). Dysregulated affect is a hallmark of many psychological disorders (Cole & Hall, 2008) and the pattern of findings of increased reactivity to a low or non-threat contexts has been found in other studies (Larson, Nitschke, & Davidson, 2007). The construct of dysregulated fear, which highlights inflexibility of behavior across eliciting contexts is consistent with other theories of psychopathology. For instance, Rottenberg hypothesizes (Rottenberg, 2005) and finds support for the prediction that depression is the result of context insensitive deficits in emotional reactivity because individuals with major depressive disorder show low emotional reactivity to both positive and negative stimuli (Rottenberg, Gross, & Gotlib, 2005).

There are a few limitations to address. First, although typical of longitudinal studies, there was notable attrition from age 2 to the kindergarten year assessments. The decision to impute the missing data resolved issues associated with biases in parameter estimates. Second, for design purposes we conducted the ADIS interviews on a partial sample, those children who were most fearful in kindergarten. Although this limited our ability to examine differences between fearful and non-fearful children, it allowed a conservative test of the predictive power of dysregulated fear within a sample of children identified as fearful in kindergarten. Third, measures of social competence were limited to teacher report. Future work should examine observed prosocial behavior. Fourth, this sample was an unselected, low-risk community sample, so overall prevalence of anxiety symptoms was low but consistent with other community samples. However, demonstrating risk for SAD symptoms in typically developing populations fits with the tenets of developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti, 1994). For future studies, in order to be able to tease apart the discrete effects of multiple risk factors, it would be important to examine whether these associations hold in other high-risk samples. For instance, how would maternal psychopathology, history of trauma or maltreatment, or exposure to violence (all of which are known risk factors for anxiety development) interact with dysregulated fear to predict risk? In addition, it would be important to examine real-world extensions of the dysregulated fear profile identified in a laboratory. Finally, the sample was not diverse and although it represented the population in the area, this may limit the generalizability of the findings beyond this population.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the ability to regulate behavior by matching one's responses to the context is important for fearful children's adjustment. In the current study, we have provided additional evidence for the predictive validity of dysregulated fear as a new way to identify fearful toddlers at risk for developing social anxiety symptoms. Identifying dysregulated fear in toddlerhood allowed us to predict which children are most likely to enter kindergarten with anxious symptoms (Buss, 2011), show more social wariness even after most kindergarteners adapt, and would manifest more SAD symptoms during childhood. Thus, the dysregulated fear construct represents a promising new avenue of exploration for developmental scientists, with the potential to inform identification of which children may be at highest risk and the creation of preventive interventions designed to ameliorate risk for the development of anxiety symptoms among temperamentally fearful children.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by two grants to the first author from the National Institutes of Health (R03MH67797, R01MH75750). Kristin Buss is also supported as a faculty member of the Children, Youth and Family Consortium at The Pennsylvania State University. We wish to thank the families who participated in this project and the staff and students of the Emotion Development Labs at University of Missouri and Penn State who helped to collect and prepare the data.

References

- Arbeau KA, Coplan RJ, Weeks M. Shyness, teacher-child relationships, and socio-emotional adjustment in grade 1. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(3):259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Arcus DM. Inhibited and uninhibited children. In: Wachs TD, Kohnstamm GA, editors. Temperament in context. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH. Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) 2003.

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Faraone SV. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy BA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, Kagan J. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:814–821. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, et al. Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(1):21–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810130023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet M, Egeland B. The development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(2):517–550. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060275. doi: S0954579406060275 [pii]10.1017/S0954579406060275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA. Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(3):804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH. Context-Specific Freezing and Associated Physiological Reactivity as a Dysregulated Fear Response. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(4):583–594. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.583. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery - Toddler Version. University of Wisconsin; Madison, Wisconsin: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, McNicol K, Doubleday E. Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(7):817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):157–168. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Fox NA. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. The emergence of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1994;55:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Cillessen AH. Peer rejection: Origins and effects on children's development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1993;2(3):89–92. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770946. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Hall SE. Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for psychopathology Child and adolescent psychopathology. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, US: 2008. pp. 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA. The stresses of a “brave new world”: Shyness and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 2008;22(4):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA, Calkins SD, et al. Being alone, playing alone, and acting alone: Distinguishing among reticence and passive and active solitude in young children. Child Development. 1994;65(1):129–137. doi: 10.2307/1131370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, Vitaro F. Childhood behavioral profiles leading to adolescent conduct disorder: risk trajectories for boys and girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1086–1094. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00009. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Rickman M. Behavioral inhibition and the emotional circuitry of the brain: Stability and plasticity during the early childhood years. In: Schulkin LASJ, editor. Extreme fear, shyness, and social phobia: Origins, biological mechanisms, and clinical outcomes. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, US: 1999. pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. doi: 10.1017/s0954579407000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: The moderating roles of childcare history, maternal personality and maternal behavior. Social Development. 2008;17(3):471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ML, Kim D-Y. Maternal and child predictors of preschool children's social competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2004;25(1):3–24. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2003.11.006. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, Larose S, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of anxiety in a population sample of children: Clarifying the role of children's behavioral characteristics and maternal parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:361–373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Cox MJ, Saluja G, Pianta RC, Bradley RH, Payne CC. Maternal sensitivity and child wariness in the transition to kindergarten. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2(4):355–377. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0204_02. [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8(3):430–457. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem0803_5. [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. The confluence of mental, physical, social and academic difficulties in middle childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):588–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Kagan J, Reznick JS. Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development. 1984;55:1005–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H. Behavioral profiles of anxious solitary children and heterogeneity in peer relations. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(6):1604–1624. doi: 10.1037/a0013303. doi: 10.1037/a0013303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Ladd GW. Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development. 2003;74(1):257–278. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Rudolph KD. Moving Toward and Away From the World: Social Approach and Avoidance Trajectories in Anxious Solitary Youth. Child Development. 2004;75(3):829–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00709.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Campos JJ. The structure of temperamental fear and pleasure in infants: A psychometric perspective. Child Development. 1990;61(6):1944–1964. doi: 10.2307/1130849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greener S, Crick NR. Normative beliefs about prosocial behavior in middle childhood: What does it mean to be nice? Social Development. 1999;8(3):349–363. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00100. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Utendale WT, Sullivan C. The Socialization of Prosocial Development. In: Hastings JEGPD, editor. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2007. pp. 638–664. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(12):1308–1316. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Psychophysiological and behavioral evidence for varying forms and functions of nonsocial behavior in preschoolers. Child Development. 2004;75(1):251–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, Rosenbaum JF. Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: a five-year follow-up. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, Bloomfield A, Biederman J, Rosenbaum J. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(4):357–367. doi: 10.1002/da.20490. doi: 10.1002/da.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):103–111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell D. The treatment of missing data. In: Outhwaite W, Turner SP, editors. The Sage Handbook of Social Science Methodology. Sage Publications, Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, Rubin KH, Rowden L, LeMare L. Children's peer relationships: Longitudinal prediction of internalizing and externalizing problems from middle to late childhood. Child Development. 1990;61(6):2004–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jeličić H, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies: The persistence of bad practices in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1195–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Temperament in Human Nature. Westwiew; Boulder: 1994. Galen's Prophecy. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Fox NA. Biology, Culture, and Temperamental Biases. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, US: 2006. pp. 167–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, Garcia-Coll C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development. 1984;55:2212–2225. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychological Science. 1991;2(1):40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1991.tb00094.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N, Kahn V, Towsley S. The preservation of two infant temperaments into adolescence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2007;72(2):1–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2007.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children's responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development. 2010;19(2):304–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Associations among Context-specific Maternal Protective Behavior, Toddlers’ Fearful Temperament, and Maternal Accuracy and Goals. Social Development. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x. no-no. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Radke-Yarrow M. Inhibition in toddlerhood and the dynamics of the child's interaction with an unfamiliar peer at age five. Child Development. 1992;63(2):325–335. doi: 10.2307/1131482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Profilet SM. The child behavior scale: A teachre-report measure of young children's aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(1008-1024) [Google Scholar]

- Larson CL, Nitschke JB, Davidson RJ. Common and distinct patterns of affective response in dimensions of anxiety and depression. Emotion. 2007;7(1):182–191. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMare LJ, Rubin KH. Perspective taking and peer interaction: Structural and developmental analyses. Child Development. 1987;58(2):306–315. doi: 10.2307/1130508. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui LH, Swendsen J. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, Buss K. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: the moderating role of attachment security. Child Development. 1996;67(2):508–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA. Social withdrawal, observed peer acceptance, and the development of self-perceptions in children ages 4 to 7 years. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2005;20(2):185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Hirshfeld-Becker DR. The developmental and psychopathology of social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(1):44–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Rosenblum K. Preschool antecedents of internalizing problems in children beginning school: The role of social maladaptation. Early Education and Development. 1998;9(2):117–129. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed0902_1. [Google Scholar]

- Peugh JL, Enders CK. Missing Data in Educational Research: A Review of Reporting Practices and Suggestions for Improvement. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74(4):525–556. doi: 10.3102/00346543074004525. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer M, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ, Rickman M. Continuity and change in inhibited and uninhibited children. Child Development. 2002;73:1474–1485. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. The development of generalized anxiety. In: Dadds MWVMR, editor. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, US: 2001. pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Early DM, Cox MJ, Saluja G, Pianta RC, Bradley RH, Payne C. Early behavioral attributes and teachers’ sensitivity as predictors of competent behavior in the kindergarten classroom. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23(4):451–470. doi: 10.1016/s0193-3973(02)00128-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Kagan J. Infant predictors of kindergarten behavior: The contribution of inhibited and uninhibited temperament types. Behavioral Disorders. 2005;30(4):331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld DR, Bolduc EA, et al. Further evidence of an association between behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Results from a family study of children from a non-clinical sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1991;25(1-2):49–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(91)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th edition John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken: 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J. Mood and Emotion in Major Depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(3):167–170. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00354.x. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Emotion Context Insensitivity in Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):627–639. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.627. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.114.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH. The Play Observation Scale (POS) University of Maryland, Center for Children, Relationships, and Culture; College Park, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Coplan RJ. Handbook of childhood social development. Blackwell; 2002. Social withdrawal and shyness. pp. 330–352. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Hastings PD. Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development. 2002;73(2):483–495. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Kennedy AE, Stewart SL. Social withdrawal in childhood. In: Barkley EJMRA, editor. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2003. pp. 372–406. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Daniels-Beirness T, Bream L. Social isolation and social problem solving: A longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52(1):17–25. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.52.1.17. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Lollis SP. Origins and consequences of social withdrawal. In: Nezworski JBT, editor. Clinical implications of attachment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ, England: 1988. pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Mills RS. The many faces of social isolation in childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):916–924. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Stewart SL. Social withdrawal. In: Mash EJ, editor. Child Psychopathology. Guilford; New York: 1996. pp. 277–307. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe L, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55(1):17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]