Abstract

Background

Individuals who report problematic drinking early in life often recover from alcohol-related disorders, with or without formal treatment. While risk factors associated with developing alcohol use disorders (AUDs), such as a family history (FH) of alcoholism and the genetically-influenced low level of response (LR) to alcohol, have been identified, less is known about characteristics that relate to remission from AUDs.

Methods

The male subjects (98% Caucasian) for this study were 129 probands from the San Diego Prospective Study who were first evaluated at age 20 as drinking but not alcohol dependent young men, most of whom were college graduates by followup. The individuals evaluated here met criteria for an AUD at their first follow-up at age 28 to 33 and were followed every 5 years for the next two decades. Discrete-time survival analysis was used to examine rates of initial and sustained AUD remission and to evaluate the relationships of premorbid characteristics and other risk factors to these outcomes.

Results

60% of the sample met criteria for an initial AUD remission of five or more years, including 45% with sustained remission (i.e. no subsequent AUD diagnosis). Higher education, lower drinking frequency, and having a diagnosis of alcohol abuse (rather than dependence) were associated with higher rates of initial AUD remission. A lower LR to alcohol at age 20, as well as lower drinking frequency, having received formal alcohol treatment, and older age at the first follow-up all predicted a greater likelihood of sustained AUD remission.

Conclusion

This study identified key factors associated with initial and sustained AUD remission in subjects diagnosed with AUD in young adulthood. Characteristics associated with better outcomes early in the lifespan, such as lower drinking frequency and early treatment appear to have a lasting impact on remission from AUD across adulthood.

Keywords: Level of Response, Alcoholism, Survival Analysis, Longitudinal, Remission

I. Introduction

Drinking practices and alcohol-related problems can fluctuate substantially from adolescence through middle age (Dubow et al., 2008; Jacob et al., 2009; Lemke et al., 2008; Maggs et al., 2008; Pitkanen et al., 2008). Characteristics that increase the risk for developing alcohol problems include a family history (FH) of alcohol use disorders (AUDs), a low level of response (LR) to alcohol, personality characteristics of impulsivity and related attributes, past alcohol problems, an earlier age of drinking onset, and a history of illicit drug use (Bacharach et al., 2004; Brennan and Moos, 1990; Ettner, 1997; Horwitz et al., 1996; Lynskey et al., 2003; Moos et al., 2004; Munro et al., 2000; Perreira et al., 2002; Trim et al., 2009; Umberson and Chen, 1994). Predictors of remission have also been evaluated regarding the approximate one-third of individuals who develop AUDs and who recover from this disorder without formal treatment (Cunningham et al., 2000; Dawson et al., 2006), and those who enter rehabilitation programs or participate in self-help groups who may have even higher rates of improvement (LoCastro et al., 2009; Mueller et al., 2007; Vaillant 2003). A better understanding of factors related to the outcomes of alcohol use and problems over time can help identify which problematic drinkers are likely to improve, and when to initiate interventions (Lemke et al, 2005; Perreira and Sloan, 2002; Sartor et al., 2003).

Cross-sectional studies of the course of alcohol problems describe correlates of AUD remissions, but longitudinal studies might better capture the complex, chronic, often fluctuating course of problematic drinking behavior. For example, across a 2-year period, AUDs were shown to have only moderate levels of diagnostic stability with a 15% recurrence rate among those who were initially remitted and a 41% persistence rate among those who were initially diagnosed (Boschloo et al., 2012). Longer studies of remission of alcohol-related problems might be even more informative, but require detailed longitudinal data on high-risk populations to increase the likelihood of observing periods of sustained remission as opposed to shorter fluctuations in the cycle of abstinence.

The probability of developing and maintaining remission is higher in individuals with: 1) less intense substance problems; 2) more stable life functioning; 3) higher incomes; 4) a spouse who encourages change; 5) greater overall social support; 6) a later age of onset of regular drinking; 7) no concomitant psychiatric diagnoses; and 8) recent histories of seeking help for drinking problems (Bischof et al., 2003; Boschloo et al., 2012; Chassin et al., 2004; Cunningham et al., 2000; Dawson et al., 2006; 2012; Satre et al., 2012). Additional characteristics associated with a better prognosis for AUDs may include having young children in the house and religiosity (Dawson et al., 2012). Many of these findings are consistent with what has been described as social processes hypothesized to facilitate long-term remission of AUDs, including evidence of social bonding, involvement in alternative rewarding activities, general life stability and abstinence-orientation (Moos, 2007).

Additional studies have highlighted the potential impact of premorbid genetically-influenced traits on the course of AUDs over time, including remission or failure to remit. It has been hypothesized that certain biologically-influenced factors predict both the development of problem drinking as well as a severe course of alcohol problems over time, especially regarding impulsivity or behavioral dyscontrol (Penick et al., 2010; Sher et al., 2005; Tarter et al., 2004). Other genetically-influenced premorbid characteristics, such as the low level of response (LR) to alcohol and FH of AUDs, may also relate to the development of AUD and, potentially, their remission. Because LR does not reflect the externalizing traits that often carry poor prognoses for AUDs and other life problems (Finn et al., 2005; Hussong et al., 2004), developing a substance-related disorder in the context of a low alcohol response may be associated with a higher chance of remission than is seen in individuals carrying other types of biologically-based predispositions. Therefore, the course of the development of AUDs and remission from alcohol problems are likely to relate to a wide range of factors, and might be best understood from a long term longitudinal study that includes evaluations of several characteristics simultaneously.

The San Diego Prospective Study (SDPS) is a longitudinal data set that examines multiple characteristics that include many of the social processes and biologically based characteristics discussed above as potentially related to the course of AUDs. The sample involves >400 men who were originally recruited as 18–25 year old healthy males who drank alcohol but were not alcoholic, made up of pairs of sons of alcoholics and controls matched on recent substance use and demography (Schuckit and Gold, 1988). The selection criteria focused on the majority of alcoholics who develop their disorder in their twenties in the absence of severe impulsivity or disinhibition (Finn et al., 2005). The men have been followed ~every 5 years for over 30 years to see how multiple social and biologically-based characteristics from ~age 20 relate to the development and course of drinking patterns and problems over the next three decades (Schuckit, 2009; Schuckit and Gold, 1988; Schuckit and Smith, 2000; Trim et al., 2009). As part of this process, our group earlier examined predictors of AUD onset and course remission data from the SDPS (Schuckit and Smith, 2011), but the emphasis was on onset and the followup after the development of an AUD was relatively short.

The current study extends these prior results by examining the 20 year course after the onset of an AUDs in probands who met criteria for an AUD at ~age 30 (by definition no subject had an AUD at baseline at about age 20). The goals of these analyses were to: (1) examine rates of both initial and sustained remission from AUDs over a 20+ year period; and (2) evaluate premorbid characteristics and other risk factors that predicted AUD remission over time. We hypothesized that genetically-influenced risk factors for AUD onset, including a low LR to alcohol and a FH of AUDs, would also predict whether a person remitted from an AUD.

II. Materials and Methods

Participants

These probands were originally recruited as ~20 year old Caucasian or Hispanic, drinking but not alcohol-dependent men through questionnaires mailed to random students and nonacademic staff at the University of California, San Diego between 1978 and 1988 (Schuckit and Gold, 1988; Schuckit and Smith, 2000). They were chosen so that about 50% of the probands had an alcohol dependent father and half the subjects did not have a biological parent or grandparent with alcohol dependence. No subjects met criteria for a major depressive or major anxiety disorder when tested at baseline. Participants were evaluated in person with a semi-structured interview based on several validated instruments, after which all participated in an alcohol challenge with 0.75ml/kg (0.61gm/kg) of ethanol, consumed over 8–10 minutes to evaluate their LR over three hours through self-reports of subjective feelings of intoxication, alterations in body sway/standing steadiness, and alcohol-related changes in cortisol (Schuckit and Gold, 1988; Schuckit and Smith, 2000).

All 453 men were located 10 years later (T10) when 99% completed interviews about their interval substance use and problems, with corroborating data gathered from an additional informant. At the 15-year follow-up (T15), 98% of the original subjects and additional informants were evaluated regarding interval functioning using an interview based on the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) instrument (Bucholz et al., 1994; Schuckit and Smith, 2000). The same data collection methods were used to gather information during the 20, 25, and 30-year follow-ups, with 90% subject retention over the 30 years. Only those probands with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) alcohol abuse or dependence at T10 (age ~30 years) were included these analyses (n=129), representing 28.7% of the 450 subjects evaluated at the 10-year followup.

Measures

LR to Alcohol

LR came from alcohol challenges at ~ age 20 as briefly described above. The LR value used z-scores to combine alcohol-related changes in subjective feelings, body sway, prolactin and cortisol into a continuous measure of alcohol response (Schuckit et al., 1988; Schuckit and Gold, 1988; Schuckit and Smith, 2000).

FH of AUDs

The history of AUDs in parents and grandparents was gathered from the FH Assessment Module (FHAM) interviews with a specificity of 98%, and a positive predictive value of ~ 50% (Rice et al., 1995). FH is a manifest variable with a score of 1 for each alcoholic parent and 0.5 for each grandparent with an AUD.

Treatment History

Each follow-up gathered details regarding the presence of any interval participation in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), alcohol-related treatment with professionals, and participation in formal inpatient or outpatient alcohol treatment programs.

Illicit Drug Use

Questions extracted from the SSAGA were used to gather information on the interval history of use and problems associated with eight categories of illicit drugs (e.g. cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, etc.), comorbid drug problems, as well as DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence.

Demographics

These variables included parent education (a proxy measure for socioeconomic status of upbringing), and T10 measures of proband’s age, marital status, presence of offspring, religiosity, education, and smoking status.

Alcohol Outcomes

The interval alcohol use and problem histories used the same modified SSAGA interview questions as incorporated at T10. The first outcome of interest was the five year period when a proband no longer met interval criteria for an AUD for the first time (“initial remission”). The second outcome considered an AUD as being in “sustained remission” if the proband did not meet criteria for AUD in any subsequent follow-up.

Data Analytic Approach

Discrete Time Survival Analysis (DTSA) was used to analyze the time to first remission and time to sustained remission from AUD. Hazard curves were developed as a function of measurement occasion of the outcome (e.g. no longer meeting criteria for an AUD during the prior 5 year interval), recording an outcome as present or absent at each follow-up (Muthén and Masyn, 2005). Follow-up epochs prior to the outcome were scored as zeros, the age of remission was recorded, and (because the individual was no longer at risk for the event) ages subsequent to an event were coded as missing (Trim et al., 2009; 2010). All continuous variables were first centered (average score subtracted from each raw score) to reduce multicollinearity, and binary variables were recorded as 0 and 1. Models were run in MPlus v6.12 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2011) with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation under the assumption of data missing at random (MAR) with robust standard errors. To increase confidence in the values, automatically generated starting values with random perturbations (100 random sets of starting values with 10 full optimizations) were used for all models.

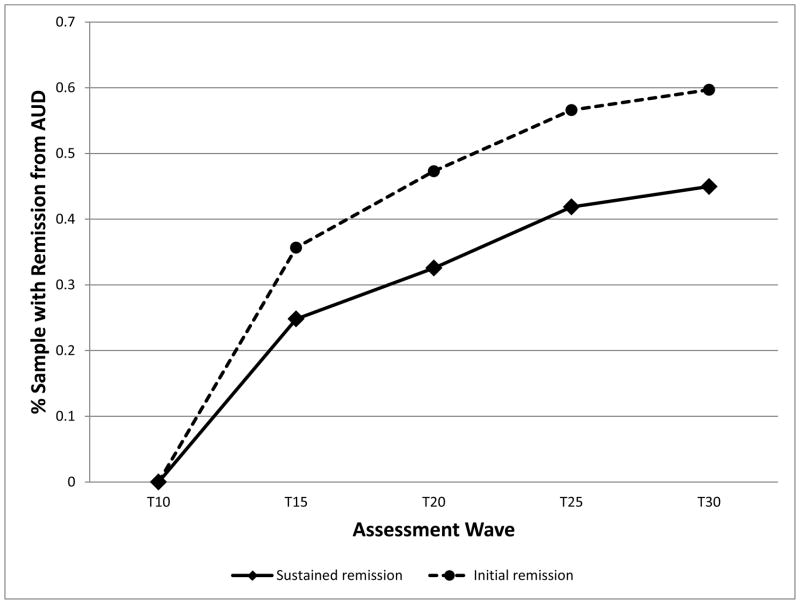

The relationships between predictors (e.g., LR) and the outcomes (e.g., initial remission) were evaluated with a series of DTSAs constructed using a latent hazard function representing the distribution of the time of AUD remission (see Figure 1). Discrete-time hazard is the conditional probability that an individual will experience the event (e.g., remission of an AUD) at an age, given he did not have the event at an earlier time point (Singer and Willett, 1991; Willett and Singer, 1993). The resulting pattern of remissions (hazard function) was then tested for significant changes over time using the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT), comparing a model constrained for no time change vs. an unconditional model.

Figure 1.

Inverse Sample Estimated Survival Probabilities for AUD Remission (n=129)

In this modeling approach, DTSA is a special case within the general latent variable framework which corresponds to a single-class latent class analysis with binary time-specific event indicators. The first step was to fit an unconditional survival model that included only the five binary time-specific event indicators for the remission of AUDs across adulthood. The constant hazard assumption was then evaluated by comparing the unconditional survival model, which allowed the hazard rate to vary across time, to a model that constrained the hazard rate to equality across intervals using a likelihood-ratio test (LRT) based on the model deviance statistics. The next step was to evaluate if predictors related to the outcome in a similar manner across ages regarding each predictor, and by comparing a model with time-varying effects to a model that constrains the predictor/covariate effects to being equal over time using a series of LRTs. If a characteristic violated proportionality, it was used in the DTSA in a manner that allows for the time-varying effects. Finally, a multivariate model that included all predictors was evaluated to allow interpretation of how each individual characteristic related to the outcome of after adjusting for all other predictors.

III. Results

These data were generated from 129 SDPS probands who met criteria for an AUD (37% abuse; 63% dependence) at the first follow-up assessment (T10). Note that no subject had an AUD at baseline. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all major predictors used here (e.g., LR) and for items likely to be covariates in the analyses as measured at baseline and T10 assessments. For these men who had developed an AUD by T10 (about age 30), more than half had a FH of AUDs, while 38% were married, 17% had children at that age, they had > 16 years of education, about a third practiced a religion, and few had had formal treatment or AA involvement. Their mean LR was represented by a z-score of −.80 which reflects a lower average LR than would be expected since this z-score at baseline was for the full sample that included both men who did and did not develop an AUD for these subjects half of whom had a FH of alcohol dependence. The 30 year old subjects at T10 had an average of ~4 drinks per drinking occasion and an average of ~17 drinking days in the past month; they reported an average of 14.0 maximum drinks (SD=5.0) on an occasion and an average of 23.8 drinking days (SD=6.5) in their heaviest month of drinking. At T10, > 40% of these men with a lifetime alcohol use disorder were also current smokers and a similar percent met criteria for an additional lifetime drug use disorder (21% cocaine dependence; 12% marijuana dependence; 6% marijuana abuse; 2% cocaine abuse; 2% amphetamine abuse). As shown toward the bottom of Table 1, 60% of these men met criteria for a period of remission (i.e. they did not met AUD criteria for at least one interval period of ~5 years) at some point following T10, while 45% met criteria for sustained remission from AUD (i.e. they did not met AUD criteria prior to and lasting through their last assessment).

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Study Variables (n=129)

| Mean | Std Dev | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 LR to alcohol | −0.80 | .75 | −3.29 – +1.47 |

| T1 Family history of AUD | 0.59 | .49 | 0–1 |

| T1 Parental education | 16.15 | 2.84 | 8–24 |

| T10 Age | 30.39 | 2.80 | 25–38 |

| T10 Married (%) | 38.0 | .49 | 0–1 |

| T10 Parented a child (%) | 17.1 | .38 | 0–1 |

| T10 Any religion practiced (%) | 32.6 | .47 | 0–1 |

| T10 Years of education | 16.74 | 2.15 | 12–20 |

| T10 Smoker in prior 5 years (%) | 42.6 | .50 | 0–1 |

| T10 Usual drinking frequency | 17.19 | 7.39 | 3–30 |

| T10 Usual drinking quantity | 4.18 | 1.71 | 2–10 |

| T10 Alcohol dependence (versus abuse) (%) | 62.8 | .49 | 0–1 |

| T10 Drug use disorder (%) | 37.2 | .49 | 0–1 |

| T10 Any formal AUD treatment | 3.9 | .19 | 0–1 |

| T10 Any involvement with AA (%) | 11.6 | .32 | 0–1 |

| Initial remission from AUD (Lifetime %) | 60.0 | .49 | 0–1 |

| Sustained remission from AUD (Lifetime %) | 45.0 | .50 | 0–1 |

Note. T1 and T10 indicate the baseline (~age 20) and 10 year follow-up; family history is based on alcohol abuse or dependence in parents and grandparents; LR (Level of response to alcohol) at baseline (~age 20) is the z-score generated by the sum of up to three variables representing change from baseline to 60 minutes after the drink of three variables during an alcohol challenge; AUD= Alcohol Use Disorders; AA= Alcoholics Anonymous; a standard drink = 10–12g ethanol.

Unconditional Survival Models

An unconditional discrete-time survival model was then fitted for the remission of AUDs across adulthood in the probands using only the binary (e.g., remission present or not) time-specific (e.g., T20) event indicators. The estimated hazard function captured the conditional probability that an individual would no longer meet criteria for an AUD in a specific age interval given that he did not remit in an earlier interval, and this was used to calculate the survival function over time. Figure 1 illustrates a steep increase in the rates of AUD remission from T10 to T15, with a lower rate of remission onset from T15 through T30. The constant hazard assumption was next evaluated to assess whether the hazard rate varied significantly across adulthood. The unconditional hazard model (with time-varying hazard rates) was found to significantly improve fit compared to a model that constrained the hazard rate to equality for initial remission (χ2(3) = 13.36, p<.01) and for sustained remission (χ2(3) = 10.73, p<.05). Thus, the constant baseline hazard assumption was rejected and the hazard function was allowed to vary across age intervals in all subsequent models for both outcomes.

Univariate Covariate Effects

The next step evaluated if the performance of each of the covariates was similar across all of the time frames, i.e., the proportionality assumption, by comparing a model with time-varying covariate effects (non-proportional) to a model that constrained the covariate effects to equality across all time points (proportional). None of the variables yielded a significantly better model fit when allowed to vary across time for either outcome. The parameter estimates (“Est” in Tables 2 and 3 which represent the log hazard odds) and corresponding hazard odds ratios (with 95% confidence interval) for the univariate effects of all potential covariates (assumed to be proportional) are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Predicting the Hazard Function of Proband AUD Remission, Univariate Effects (n=129)

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Remission

|

Sustained Remission

|

|||||

| Est (SE) | t | OR (95% CI) | Est (SE) | t | OR (95% CI) | |

| T1 LR to alcohol | −.15 (.18) | −.81 | .86 (.60–1.23) | −.35 (.21)┼ | −1.71 | .71 (.47–1.06) |

| T1 Family history of AUD | −.05 (.27) | −.17 | .95 (.56–1.61) | −.06 (.30) | −.21 | .94 (.52–1.70) |

| T1 Parental education | −.07 (.05) | −1.45 | .93 (.85–1.03) | −.12 (.06)* | −2.20 | .89 (.79–.99) |

| T10 Age | .06 (.05) | 1.27 | 1.06 (.96–1.17) | .08 (.05) | 1.51 | 1.08 (.98–1.19) |

| T10 Married | −.16 (.29) | −.56 | .85 (.48–1.50) | −.45 (.32) | −1.42 | .64 (.34–1.19) |

| T10 Parent | −.28 (.40) | −.70 | .76 (.35–1.66) | −.53 (.45) | −1.17 | .59 (.24–1.42) |

| T10 Any religion practiced | −.07 (.29) | −.25 | .93 (.53–1.65) | −.23 (.32) | −.74 | .80 (.42–1.49) |

| T10 Years of education | .10 (.07) | 1.47 | 1.11 (.96–1.27) | .01 (.07) | .10 | 1.01 (.88–1.16) |

| T10 Smoker | .16 (.27) | .58 | 1.17 (.69–1.99) | .20 (.29) | .69 | 1.22 (.67–2.16) |

| T10 Usual drinking frequency | −.04 (.02)* | −2.40 | .96 (.92–.99) | −.06 (.02)** | −2.95 | .94 (.91–.98) |

| T10 Usual drinking quantity | −.07 (.08) | −.86 | .93 (.80–1.09) | −.03 (.09) | −.33 | .97 (.81–1.16) |

| T10 Alcohol dependence (versus abuse) | −.85 (.28)** | −3.04 | .43 (.25–.74) | −.45 (.30) | −1.50 | .64 (.35–1.15) |

| T10 Drug use disorder | −.48 (.29)┼ | −1.65 | .62 (.35–1.09) | −.54 (.32)┼ | −1.71 | .58 (.31–1.09) |

| T10 Any formal AUD treatment | 1.51 (.51)** | 2.94 | 4.53 (1.67–12.30) | 1.18 (.61)┼ | 1.94 | 3.25 (.98–10.76) |

| T10 Any involvement with AA | .73 (.43)┼ | 1.71 | 2.08 (.89–4.82) | .27 (.43) | .62 | 1.31 (.56–3.04) |

p<.10.

p< .05.

p<.01.

Note. Est= log hazard odds of AUD remission; SE= standard error; t= Est/SE (t-statistic); OR= hazard odds ratio; CI= confidence interval

Table 3.

Predicting the Hazard Function of Proband AUD Remission, Full Multivariate Model (n=129)

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Remission

|

Sustained Remission

|

|||||

| Est (SE) | t | OR (95% CI) | Est (SE) | t | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||||

| T1 LR to alcohol | −.36 (.20)┼ | −1.80 | .70 (.47–1.03) | −.65 (.24)** | −2.72 | .52 (.33–.84) |

| T1 Family history of AUD | −.20 (.30) | −.69 | .82 (.45–1.47) | −.15 (.37) | −.40 | .86 (.42–1.78) |

| T1 Parental education | −.04 (.05) | −.83 | .96 (.87–1.06) | −.08 (.06) | −1.26 | .92 (.82–1.04) |

| T10 Age | .08 (.06) | 1.43 | 1.08 (.96–1.22) | .18 (.06)** | 2.78 | 1.20 (1.06–1.35) |

| T10 Married | −.58 (.37) | −1.57 | .56 (.27–1.16) | −.73 (.43)┼ | −1.68 | .48 (.21–1.12) |

| T10 Parent | .73 (.54) | 1.35 | 2.08 (.72–5.98) | −.02 (.65) | −.03 | .98 (.27–3.50) |

| T10 Any religion practiced | −.14 (.31) | −.46 | .87 (.47–1.60) | −.24 (.37) | −.64 | .79 (.38–1.62) |

| T10 Years of education | .15 (.07)* | 2.09 | 1.16 (1.01–1.33) | .05 (.08) | .63 | 1.05 (.90–1.23) |

| T10 Smoker | .35 (.29) | 1.23 | 1.42 (.80–2.51) | .47 (.32) | 1.47 | 1.60 (.85–3.00) |

| T10 Usual drinking frequency | −.06 (.02)** | −2.86 | .94 (.91–.98) | −.08 (.02)** | −3.10 | .92 (.89–.96) |

| T10 Usual drinking quantity | .04 (.10) | .36 | 1.04 (.86–1.27) | .01 (.12) | .06 | 1.01 (.80–1.28) |

| T10 Alcohol dependence (versus abuse) | −1.09 (.37)** | −2.98 | .34 (.16–.69) | −.47 (.41) | −1.14 | .63 (.28–1.40) |

| T10 Drug use disorder | −.38 (.31) | −1.22 | .68 (.37–1.26) | −.49 (.35) | −1.39 | .61 (.31–1.22) |

| T10 Any formal AUD treatment | 1.71 (.94)┼ | 1.82 | 5.53 (.88–34.90) | 2.38 (.90)** | 2.65 | 10.80 (1.85–63.05) |

| T10 Any involvement with AA | .82 (.55) | 1.47 | 2.27 (.77–6.67) | −.23 (.57) | −.41 | .79 (.26–2.43) |

p<.10.

p< .05.

p<.01.

Note. Est= log hazard odds of AUD remission; SE= standard error; t= Est/SE (t-statistic); OR= hazard odds ratio; CI= confidence interval

For the outcome of initial, or first, remission a person experienced in Table 2, three predictors were significant at p<.05 (two others were marginally significant at p<.10 and are mentioned here because these same items are sometimes significant in additional analyses): Usual drinking frequency and alcohol dependence (versus abuse) at T10 were significantly negatively related to initial remission such that drinking less frequently and having alcohol abuse (instead of dependence) at T10 were associated with initial remission; while having had formal AUD treatment at T10 was significantly positively associated with initial remission. For the trends, having a drug use disorder was negatively and having had AA involvement at T10 tended to be positively associated with initial AUD remission.

For the outcome of sustained remission (achieving and maintaining remission over time), two predictors were significant (three others were marginally significant): Parental education and typical drinking frequency were negatively related to sustained AUD remission such that having parents with less formal education and drinking less frequently at T10 were associated with sustained AUD remission. For the trends, a lower LR to alcohol, not having a drug use disorder, and already having had formal AUD treatment at T10 were somewhat associated with sustained AUD remission.

Full Multivariate Survival Models

Table 3 presents a full multivariate model which extends the information in Table 2 by estimating all covariates simultaneously to determine each individual covariate effect on AUD remission after adjusting for all other covariates. For the outcome of initial remission, three predictors were significant at p<.05 (two others were marginally significant at p<.10): Higher typical drinking frequency and alcohol dependence (versus abuse) at T10 were negatively related to initial remission such that drinking less frequently and having alcohol abuse (instead of dependence) at T10 were associated with initial remission (similar to the univariate effects); for these probands, having a higher level of education at T10 predicted initial AUD remission. For the marginal effects (trends), a lower LR and having had formal AUD treatment at T10 tended to be associated with a lower rate of initial AUD remission.

For the outcome of sustained remission, four predictors were significant at p<.05 (one other was marginally significant at p<.10): Having a lower LR to alcohol, a lower typical frequency of drinking at T10, having received formal alcohol treatment at T10, and older age at T10 all predicted greater likelihood of sustained AUD remission. There was a trend that not being married at T10 was marginally related to sustained remission.

Interpretation of the hazard odd ratios for the significant predictors in the full models in Table 3 is warranted as these effects are robust even when controlling for the range of other predictor variables. For initial remission, individuals with a 1-year higher education had a rate of initial AUD remission 16% higher than those with less education (OR=1.16); those with a 1-day higher T10 drinking frequency had a rate of initial remission 6% lower (OR=0.94) than those with the lower drinking frequency; and probands with T10 alcohol dependence had a rate of initial remission 66% lower (OR=.34) compared to those with alcohol abuse at T10. For sustained remission, probands with a 1-year higher age at T10 had AUD sustained remission at a 20% higher rate than those with younger ages (OR=1.20); those with a 1-day higher T10 drinking frequency had a sustained remission rate 8% lower (OR=0.92) than those with the lower drinking frequency; and rates of sustained remission were ~10 times greater among probands who had received formal AUD treatment by T10 (OR=10.8); the hazard odds ratio for the continuous LR score was difficult to place into the same perspective due to prior standardization and log-transformation of the LR scores. Therefore, the full model from Table 3 was re-run using a dichotomous measure of LR based on a median split of the continuous LR score used in these analyses, revealing that the AUD sustained remission rate among higher LR subjects was 68% less than among lower LR subjects (OR=0.32).

IV. Discussion

This paper presents the 20-year pattern of remission from alcohol abuse or dependence for 129 men who had developed their disorder prior to age 30. The subjects were probands from the SDPS who had entered the protocol at ~age 20, when they had experience with alcohol, did not fulfill criteria for an AUD, and were students or nonacademic staff who, therefore, did not fit the pattern of early onset AUDs likely to be associated with additional drug problems and impulsivity and to carry a poorer prognosis. All those included in these analyses developed alcohol abuse or dependence by ~age 30 (T10) and they were followed up every five years through about ~age 50 (T30).

During the course of the follow-up, 60% of these alcoholic probands reported at least one five-year period during which they experienced none of the 11 DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence criterion items. That figure includes 45% for whom the period of remission sustained through the most recent follow-up assessment at ~age 50. The pattern of remission over the 20 years indicates that both initial and sustained remissions were likely to occur during each of the follow-up epochs, with the greatest incidence of remission from AUD occurring between age 30 (T10) and age 35 (T15).

Most analyses focused on the pattern of a limited number of social and biological predictors from baseline, at a time before the onset of an AUD, and from age 30 after the onset of an AUD. The most consistent predictor of initial and/or sustained remission across the outcomes was a lower usual frequency of drinking at T10. This item might reflect the salience of alcohol in the person’s life, despite the presence of alcohol-related problems. The next most consistent predictor of subsequent remission was the exposure to formal AUD treatment during the period prior to T10. Although the proportion of men with AA or formal treatment was small, such experiences early in life may have taught them the need for ongoing vigilance regarding future alcohol problems. It is also possible that alcoholic men with a greater drive to recover were those who sought out help early in their problematic alcohol use.

The third relatively consistent predictor of alcohol remission was the low LR to alcohol which contributed as a trend for initial remission and was a significant predictor for sustained remission. This endophenotype is one of several genetically-influenced characteristics observed early in life that predict later AUDs, and has a modest effect size (Schuckit, 2009b). Compared to some other endophenotypes (e.g., impulsivity), the low LR is not as closely associated with the development of multiple substance use disorders or major psychiatric symptoms later in life. While LR significantly predicted the development of an AUD, it may not be as closely associated with high levels of life problems and lower life stability outside the alcohol domain, and such comorbidities are associated with a worse prognosis among alcoholics (Crum et al., 2008; Hasin et al., 1996). Thus, an individual who develops an AUD in the context of a low LR might be less likely to have interpersonal, social, and personality characteristics that interfere with the recognition that a problem exists and might demonstrate a greater ability to address life problems associated with heavy drinking.

Additional T10 predictors that related to initial or sustained remission in the final multivariate model included older age when interviewed, a higher level of education, and a trend for not being married. While these demographic characteristics might reflect greater maturity, stability, or higher life achievements, these items (as well as parental education) did not contribute in a consistent manner across outcomes.

Two other potential predictors of remission are worth mentioning. First, the diagnosis of alcohol abuse (versus dependence) was associated with initial, but not with sustained remission. Abuse (requiring one of four items) has a more easily fulfilled threshold than does dependence (requiring three of seven items). Also, from a clinical perspective, the abuse items may reflect consequences of drinking that are not closely linked to the dependence syndrome proposed by Edwards and Gross (1976). In addition, studies have reported that the probability of maintaining a diagnosis of abuse over time is lower than the probability of maintaining dependence (Hasin et al., 1997; Schuckit and Smith, 2011). These factors may have contributed to why an abuse diagnosis, as opposed to dependence, might indicate a greater probability for initial, but not sustained AUD remission as found in the current study.

It is of interest to note that the family history of an AUD did not predict either initial or sustained remission from an AUD over time. This might reflect the fact that the probands were relatively highly functional individuals and that many of the characteristics mentioned here (e.g., the LR to alcohol, the alcohol intake pattern, and so on) might have overridden any impact from FH alone. This finding is consistent with one previous study that found FH of AUD did not predict AUD remission at a 40-year follow-up (Knop et al., 2007).

It is worthwhile to comment on the high rate of remission in these subjects. These probands had many of the factors associated with relatively good prognoses in alcoholics, including higher education, good job skills, generally supportive families, the absence of severe antisocial behaviors, the low rate of drug dependence, and few independent psychiatric disorders (e.g. Bischoff et al., 2003; Boschloo et al., 2012; Moos, 2007; Satre et al., 2012). In light of the fact that the lifetime rate of AUDs in middle class and more affluent men is similar to the general population rate, the current subjects may be more representative of the course of remission in the usual alcoholic than are treatment samples, especially those from studies that recruit subjects from treatment centers that serve the indigent or individuals with multiple psychosocial stressors.

This study has several strengths, including the fact that young individuals with a low LR may be amenable to changing heavy drinking habits, a hypothesis that is the focus of a recent prevention study (Schuckit et al., 2012). However, all subjects were male, Caucasian or Hispanic, and were relatively educated and highly functional despite their AUDs. Thus, the generalization of the current results to women, individuals from lower socioeconomic strata, and those with early onset AUDs associated with impulsivity or additional psychiatric conditions was not determined. Furthermore, the current sample of alcoholics was relatively small. Additional caveats include the relatively long assessment interval of AUDs at each follow-up, the limited number of predictors used, and the strict requirement that probands were considered to have maintained an AUD diagnosis if they met one or more of the 11 criteria at any point during the ~5 years since their previous interview.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA05526 (PI: Schuckit) and by the Alcohol Beverage Medical Research Foundation (ABMRF)/The Foundation for Alcohol Research (PI: Trim).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ, Vashdi D. Retirement, risky alcohol consumption and drinking problems among blue-collar workers. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U, Meyer C, John U. Types of natural recovery from alcohol dependence: a cluster analytic approach. Addiction. 2003;98:1737–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, Smit JH, Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH. Predictors of the 2-year recurrence and persistence of alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2012;107:1590–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Moos RH. Life stressors, social resources, and late-life problem drinking. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:491–501. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Helzer JE, Shayka JJ, Lewis CE. Comparison of alcohol dependence in subjects from clinical, community, and family studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1091–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Green KM, Storr CL, Chan YF, Ialongo N, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Depressed mood in childhood and subsequent alcohol use through adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:702–712. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Lin E, Ross HE, Walsh GW. Factors associated with untreated remissions from alcohol abuse or dependence. Addict Behav. 2000;25:317–321. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJJ, Grant BF. Correlates of recovery from alcohol dependence: A prospective study over a 3-year follow-up interval. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1268–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Estimating the effect of help-seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2006;101:824–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR. Childhood and adolescent predictors of early and middle adulthood alcohol use and problem drinking: the Columbia County Longitudinal Study. Addiction. 2008;103:36–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: Provisional description of a clinical syndrome. Br Med J. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL. Measuring the human cost of a weak economy: Does unemployment lead to alcohol abuse? Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn P, Bobova L, Wehner E, Fargo S, Rickert M. Alcohol expectancies, conduct dilorder, and early-onset alcoholism. Addiction. 2005;100:953–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Tsai WY, Endicott J, Mueller TI, Coryell W, Keller M. Five-year course of major depression: effects of comorbid alcoholism. J Affect Disord. 1996;41:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Differentiating DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: Community heavy drinkers. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR, Howell White S. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. J Marriage Fam. 1996;58:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong A, Curran P, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Carrig M. Substance abuse hinders desistance in young adults’ antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:1029–1046. doi: 10.1017/s095457940404012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Koenig LB, Howell DN, Wood PK, Haber JR. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the fifties among alcohol dependent men. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:859–869. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop J, Penick EC, Nickel EJ, Mednick SA, Jensen P, Manzardo AM, Gabrielli WF. Paternal alcoholism predicts the occurrence but not the remission of alcohol drinking at a 40-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, Moos RH. Sequencing the lifetime onset of alcohol-related symptoms in older adults: Is there evidence of disease progression? J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:756–765. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, Moos RH. Gender differences in social influences and stressors linked to increased drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:695–702. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoCastro JS, Youngblood M, Cisler RA, Mattson ME, Zweben A, Anton RF, Donovan DM. Alcohol treatment effects on secondary nondrinking outcomes and quality of life: The COMBINE Study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:186–196. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Day C, Hall W. Alcohol and other drug use disorders among older-aged people. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:125–133. doi: 10.1080/09595230100100552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008;103:7–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based processes that promote the remission of substance use disorders. Clinl Psychol Rev. 2007;27:537–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Schutte K, Brennan P, Moos BS. Ten-year patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems among older women and men. Addiction. 2004;99:829–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SE, Petitjean S, Boening J, Wiesbeck GA. The impact of self-help group attendance on relapse rates after alcohol detoxification in a controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:108–112. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro CA, Saxton J, Butters MA. The neuropsychological consequences of abstinence among older alcoholics: A cross-sectional study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(10):1510–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Masyn K. Discrete-time survival mixture analysis. J Educ Behav Stats. 2005;30:27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penick EC, Knop J, Nickel EJ, Jensen P, Manzardo AM, Lykke-Mortensen E, Gabrielli WF. Do premorbid predictors of alcohol dependence also predict the failure to recover from alcoholism? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:685–694. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Sloan FA. Excess alcohol consumption and health outcomes: a 6-year follow-up of men over age 50 from the health and retirement study. Addiction. 2002;97:301–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen T, Kokko K, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. A developmental approach to alcohol drinking behaviour in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8 to age 42. Addiction. 2008;103:48–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JP, Reich T, Bucholz KK, Neuman RJ, Fishman R, Rochberg N, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Schuckit MA, Begleiter H. Comparison of direct interview and family history diagnoses of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Jacob T, Bucholz KK. Drinking course in alcohol-dependent men from adolescence to midlife. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:712–719. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Effects of age and life transitions on alcohol and drug treatment outcome over nine years. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:459–468. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet. 2009a;373:492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. An overview of genetic influences in alcoholism. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009b;36:S5–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Gold EO. A simultaneous evaluation of multiple markers of ethanol placebo challenges in sons of alcoholics and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:211–216. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Risch SC, Gold EO. Alcohol consumption, ACTH level, and family history of alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1391–1395. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Kalmijn JA, Smith TL, Saunders G, Fromme K. Structuring a college alcohol prevention program on the level of response to alcohol model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1244–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of a family history of alcohol dependence, a low level of response to alcohol and six domains of life functioning to the development of alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:827–835. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Onset and course of alcoholism over 25 years in middle class men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Modeling the days of our lives - Using survival analysis when designing and analyzing longitudinal studies of duration and the timing of events. Psychol Bull. 1991;110:268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of the level of response to alcohol and additional characteristics to alcohol use disorders across adulthood: A discrete-time survival analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1562–1570. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Predicting drinking onset with discrete-time survival analysis in offspring from the San Diego Prospective Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Chen MD. Effects of a parent’s death on adult children – Relationship salience and reaction to loss. Am Soc Rev. 1994;59:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men. Addiction. 2003;98:1043–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery – Why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]