Abstract

Objectives

To assess radiation exposure due to CT in the Netherlands.

Methods

Twenty-one hospitals participated in a dose survey for the 21 most frequently used CT protocols. Hospitals completed a Web survey with detailed parameters for one patient per protocol, including the dose length product (DLP) from the scanner dose report. Only standard-sized patients (1.74 m and 77 kg and BMI 25.4 kg/m2 ± 15 %) for each protocol and available scanner were considered. Effective dose (E) per protocol was estimated using ICRP-103-based E/DLP coefficients. Dose levels were compared to surveys from other countries and to diagnostic reference levels.

Results

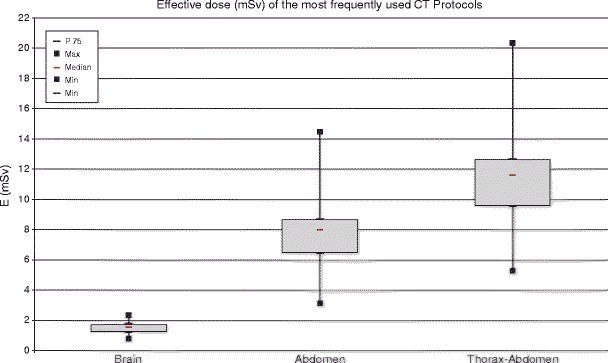

Data of 186 patients (247 scan phases) from 14 hospitals and 19 scanners were used for final analysis of DLP and E. Effective doses varied from 0.2 mSv in sinus CT to 19.4 mSv for multiphase liver. The most frequent exams were brain (1.5 mSv), abdomen (8.0 mSv), and thorax-abdomen (11.5 mSv). These results are lower than in Germany and comparable to those in the UK, and are within reference levels. Results between hospitals varied, with per protocol minimum/maximum E ratios ranging from 1.1–5.4.

Conclusions

Compared to surrounding countries, CT in the Netherlands is associated with relatively low radiation doses in standard patients. Important differences remain between hospitals.

Main Messages

• A national dose survey providing updated, detailed data for patient dose in the most frequently used CT protocols.

• CT in the Netherlands is associated with relatively low individual radiation doses in standard patients compared to surrounding European countries.

• Considerable differences remain between hospitals for the most frequently used CT protocols, indicating the need for further optimisation.

Keywords: Radiation dosage, Tomography, X-ray computed, Health care surveys, Sievert units, Gray units

Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) is an important diagnostic imaging modality that plays a key role in medical diagnosis. The number of CT examinations has shown a steady increase, and recent reports estimate that in the USA 62 million examinations per year are performed with an estimated growth of 8–10 % per year [1, 2]. In the USA, patient exposures associated with medical imaging have become the leading source of exposure of the population. In medical imaging, CT is the most important contributor to patient exposures [1–3].

In the European Union, member states are obliged to survey dose data following Article 12 of EU Directive 97/43/Euratom. The last evaluation of measured CT doses in the Netherlands was the “Demonstration Project Patient Dosimetry Radiology” (DP), which ran in 2001–2004 in 11 institutions, collecting specific data on 24 radiographic and 11 CT indications [5]. In subsequent years, only rough estimations of population dose have been made based on the information on the number of CT studies and type of CT scans derived from yearly data collections of medical imaging practice in the Netherlands. A disadvantage was that these routine yearly data collections were based on financial billing codes and not on actual practical clinical CT protocols or on CT dose assessment; therefore, they only yielded basic data, limiting the usefulness for clinical practice or for feedback.

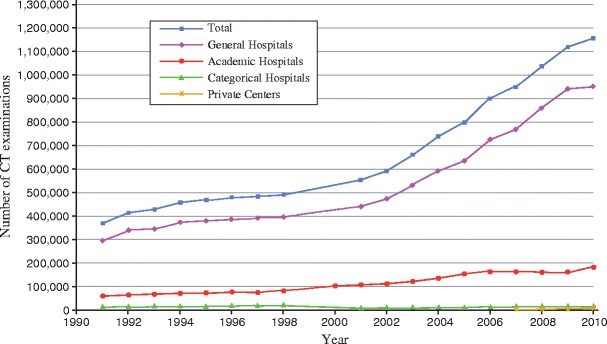

In the Netherlands in 2010, about 9.8 million diagnostic imaging studies were performed using ionising radiation. Of these, 1.16 million were CT studies, doubling the number compared to 2002 (Figure 1). The average dose to the Dutch population associated with medical imaging was estimated to be 0.89 milliSievert (mSv). CT's contribution to this dose was 0.42 mSv (47.5 %), while other big contributors were angiography and interventions (22.3 %), conventional radiography and mammography (17.6 %), and nuclear medicine (11.0 %) [4]. Thus, while the above estimations were based on the actual number of diagnostic studies in 2010, the effective doses used for the estimations were taken from the DP study [5].

Fig. 1.

Trends in the number of CT examinations 1991–2010

This survey is similar in design to previous surveys performed in Germany [6, 7] and the UK [8, 9]. But in contrast to all but the newest UK survey, our protocols were based on the frequency of use in clinical practice, and new ICRP-103 conversion factors were used throughout.

The goal of the present survey was to renew the estimation of patient dose from multidetector CT and to improve the usefulness of the data for daily clinical practice by collecting dose data on the most frequently used CT protocols.

Materials and methods

Hospital and CT protocol selection

For this CT dose survey, a set of 21 hospitals was selected randomly from all hospitals in the country with a balance among general hospitals, categorical hospitals, and academic hospitals.

In an initial phase, the CT practice in these 21 participating hospitals was surveyed for a few days. The observed practices resulted in a list of 21 CT protocols representing the CT examinations responsible for more than 90 % of the annual CT effective dose and more than 80 % of the number of CT exams done in the Netherlands (Table 1). They formed the basis for the subsequent CT part of the National Survey on Radiation Dose (NSRD-CT).

Table 1.

Dose results of CT protocols used in this national survey on CT radiation doses

| Protocol name | Clinical indication | Relative frequency (%) | Median scan range (mm) | Median (P75) DLP (mGy cm) | Median (P75) E103 (mSv) | Ratio max/min E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | Haemorrhage | 23.8 | 155 | 813.7 (935.6) | 1.5 (1.8) | 3.3 |

| Sinus | Sinusitis | 9.0 | 116 | 105.7 (133.4) | 0.2 (0.3) | 4.9 |

| Neck | Standard | 2.3 | 252 | 329.9 (404.3) | 1.7 (2.1) | 2.2 |

| Neck-thorax-abdomen | Standard | 0.7 | 880 | 985.1 (1,117.6) | 13.8 (15.6) | 1.7 |

| Thorax | Standard | 6.6 | 313 | 320.0 (346.5) | 4.6 (5.0) | 2.8 |

| Thorax-liver | Lung cancer | 4.1 | 401 | 542.0 (608.1) | 8.1 (9.1) | 2.7 |

| Thorax-abdomen | Standard | 9.5 | 687 | 813.8 (885.7) | 11.6 (12.6) | 3.9 |

| Thorax HR | Interstitial Dz | 3.1 | 273 | 142.8 (276.1) | 2.1 (4.0) | 13.4 |

| Abdomen | Standard | 20.0 | 441 | 567.0 (618.0) | 8.0 (8.7) | 4.8 |

| Abdomen low-dose | Urolithiasis | 2.1 | 399 | 301.6 (329.4) | 4.5 (4.9) | 3.3 |

| CT urography | Haematuria | 2.8 | 452 | 708.0 (981.6) | 10.0 (13.8) | 2.5 |

| Liver multiphasic | Liver Tx | 1.1 | 419 | 1,322.2 (1,496.6) | 19.4 (22.4) | 1.4 |

| Pancreas multiphasic | Adeno ca | 0.6 | 409 | 899.0 (1,000.0) | 13.2 (14.7) | 2.0 |

| Kidney multiphasic | RCC | 0.4 | 381 | 1,166.5 (1,371.2) | 17.0 (20.2) | 3.1 |

| CT coronary angio | CAD | 1.5 | 125 | 516.5 (671.4) | 13.5 (20.1) | 3.0 |

| CT pulmonary angio | PE | 4.8 | 279 | 291.5 (371.0) | 4.2 (5.4) | 2.7 |

| CTA total aorta | Dissection | 0.7 | 666 | 822.5 (836.8) | 11.7 (11.9) | 1.1 |

| CTA abdominal aorta | AAA | 1.8 | 474 | 555.5 (727.1) | 7.8 (10.3) | 3.8 |

| C-Spine | Standard | 2.5 | 213 | 276.0 (320.9) | 1.4 (1.6) | 5.4 |

| L-Spine | Standard | 1.5 | 171 | 308.2 (405.5) | 4.3 (5.7) | 3.2 |

| Bony pelvis | Standard | 1.0 | 223 | 332.0 (382.1) | 4.3 (4.9) | 1.6 |

P75 75th percentile, DLP dose length product, E103 effective dose according to ICRP-103, Dz disease, Tx transplantation, ca carcinoma, RCC renal cell cancer, CAD coronary artery disease, PE pulmonary embolism, AAA abdominal aortic aneurysm

Nationwide dose survey in CT

Based on the methodology used in the prior demonstration project [5], a Web survey was developed together with the data analysis department of the National Institute for Public Health and Environment RIVM (RIVM, Bilthoven, the Netherlands) from the Ministry of Health. A survey users' guide was available to the participants, which included detailed protocol descriptions for guidance.

The hospitals were asked to complete a Web survey with detailed parameters for one standard-sized patient per protocol, including the dose length product (DLP) extracted from the scanner dose report. For all scan phases of each protocol, participants were required to record data on: (1) patient parameters [sex, weight, length, body mass index (BMI)], (2) scanner type and parameters of the scan technique [tube voltage (kV), tube current (mA), rotation time], and (3) type and settings of automatic exposure control (AEC) and tube current modulation [TCM; noise index (NI), standard deviation (SD), or reference mean effective tube load (mAs)].

Since the DLP was taken from the scanner dose report, overrange was taken into consideration. We studied local protocols for given clinical indications. In these local protocols, the kV could be variable per scan phase. Tube current modulation techniques were employed as defined in the local scan protocols.

Patient selection

As effective dose has only been defined for normal-sized patients, the average patient in the Netherlands [10] with a margin ± 15 % was taken as a basis for patient selection. Therefore, patients were only used in the final dose analysis if their parameters were within the body weight range of 65.0–89.0 kg, body size of 1.61–1.87 m, and BMI of 21.6–29.2 kg/m2.

Radiation dose parameters and calculations

Dose parameters such as (achieved) average effective mAs, volume CT dose index (CTDIvol), and dose-length product (DLP) were recorded for each scan phase from the dose report. Effective dose (E) was estimated by multiplying the DLP by recently established ICRP-103-based E/DLP coefficients for the relevant anatomical regions for multidetector CT (for 120 kV: head 0.0019; neck 0.0051; thorax 0.0145; abdomen 0.0153; pelvis 0.0129; for the weighted averages for multiregional scanning: neck-thorax 0.0134; thorax-abdomen 0.0149; abdomen-pelvis 0.0141; thorax-abdomen-pelvis 0.0142; neck-thorax-abdomen-pelvis 0.0138 [11]). In comparison, values using ICRP-60 for 120 kV would have been: head 0.0016; neck 0.0057; thorax 0.0136; abdomen 0.0155; pelvis 0.0167. The weighted averages for multiregional scanning are: neck-thorax 0.0130; thorax-abdomen 0.0145; abdomen-pelvis 0.0161; thorax-abdomen-pelvis 0.0152; neck-thorax-abdomen-pelvis 0.0148 [11]. No dosimetry measurements were performed on site.

Multiregional scanning

In multiregional scanning, given the clinical indication, the anatomy can be scanned in either one scan (1 phase scanning, 1P) or two separate scans (2 phase scanning, 2P). Table 2 lists those patients scanned in one phase and those in two separately. Differences in data come from differences in overranging and from the use of slightly different E/DLP conversion factors.

Table 2.

Dose results of individual phases used in this National Survey on Radiation Doses in CT

| Protocol name | Type scanning | Median scan range (mm) | Median (P75) DLP (mGy cm) | Median (P75) E103 (mSv) | Ratio max/min E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | S | 160 | 806.0 (1,023.5) | 1.5 (1.9) | 3.3 |

| H | 146 | 901.6 (918.6) | 1.7 (1.7) | 1.1 | |

| Sinus | H | 116 | 106.4 (136.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | 4.9 |

| Neck | H | 252 | 329.9 (404.3) | 1.7 (2.1) | 2.2 |

| Neck–thorax-abdomen | H 1P | 872 | 968.1 (985.1) | 16.2 (16.6) | 1.3 |

| H 2P Neck | 241 | 280.0 (334.0) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.5 | |

| H 2P Tx-Abd | 648 | 824.0 (850.0) | 11.7 (12.1) | 1.4 | |

| Thorax | H | 313 | 320.0 (346.5) | 4.6 (5.0) | 2.8 |

| Thorax-liver | H 1P | 396 | 383.0 (577.0) | 5.7 (8.6) | 2.3 |

| H 2P Tx | 320 | 279.7 (300.8) | 4.1 (4.4) | 1.6 | |

| H 2P Liver | 241 | 277.4 (362.3) | 4.2 (5.5) | 2.1 | |

| Thorax-abdomen | H 1P | 630 | 764.5 (970.0) | 10.9 (13.8) | 3.7 |

| H 2P Tx | 293 | 279.1 (298.3) | 4.0 (4.3) | 4.6 | |

| H 2P Abd | 437 | 511.3 (551.1) | 7.2 (7.8) | 2.5 | |

| Thorax HR | S Insp | 270 | 55.0 (55.0) | 0.8 (0.8) | 2.3 |

| S Exp | 160 | 4.0 (4.5) | 0.1 (0.1) | 1.5 | |

| H Insp | 318 | 271.5 (378.4) | 3.9 (5.5) | 3.4 | |

| H Exp | 301 | 19.9 (30.3) | 0.3 (0.4) | 4.4 | |

| Abdomen | H Portal | 441 | 567.0 (618.0) | 8.0 (8.7) | 4.8 |

| Abdomen low dose | H Unenhanced | 399 | 301.6 (329.4) | 4.5 (4.9) | 3.3 |

| CT urography | H Unenhanced | 412 | 328.0 (404.3) | 4.6 (5.7) | 5.7 |

| H Nephrographic-excretory | 452 | 490.3 (564.7) | 6.9 (8.0) | 1.8 | |

| Liver multiphasic | H Unenhanced | 240 | 265.6 (308.0) | 4.1 (4.7) | 1.6 |

| H Arterial | 237 | 337.0 (349.3) | 5.2 (5.3) | 2.0 | |

| H Portal | 419 | 490.0 (677.5) | 6.9 (9.6) | 2.3 | |

| H Delayed | 237 | 307.0 (372.2) | 4.7 (5.7) | 2.0 | |

| Pancreas multiphasic | H Unenhanced | 189 | 193.0 (224.0) | 3.0 (3.4) | 2.7 |

| H Pancreatic | 180 | 172.0 (242.0) | 2.6 (3.7) | 3.2 | |

| H Portal | 409 | 464.0 (509.6) | 6.5 (7.2) | 1.8 | |

| Kidney multiphasic | H Unenhanced | 231 | 295.0 (346.3) | 4.3 (5.3) | 2.2 |

| H Corticomed | 202 | 391.0 (538.5) | 5.7 (8.1) | 4.8 | |

| H Nephrogenic | 381 | 331.0 (351.0) | 4.9 (5.1) | 1.5 | |

| H Excretory | 393 | 616.0 (623.0) | 8.7 (8.8) | 1.8 | |

| CT coronary angio | S Calcium | 140 | 48.1 (50.6) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.6 |

| H Arterial | 125 | 492.4 (622.1) | 14.8 (18.7) | 2.7 | |

| CT pulmonary angio | H Arterial | 279 | 291.5 (371.0) | 4.2 (5.4) | 2.7 |

| CTA total aorta | H Arterial | 666 | 822.5 (836.8) | 11.7 (11.9) | 1.1 |

| CTA abdominal aorta | H Arterial | 474 | 555.5 (627.6) | 7.8 (8.8) | 2.0 |

| C-Spine | H Unenhanced | 213 | 276.0 (320.9) | 1.4 (1.6) | 5.4 |

| L-Spine | H Unenhanced | 171 | 308.2 (405.5) | 4.3 (5.7) | 3.2 |

| Bony pelvis | H Unenhanced | 223 | 332.0 (382.1) | 4.3 (4.9) | 1.6 |

P75 75th percentile, DLP dose length product, E103 effective dose according to ICRP-103, Dz disease, S sequential, H helical, 1P one phase, 2P two phases, Insp inspiration, Exp expiration, Tx thorax, Abd abdomen

Data selection

Outliers for CTDIvol and DLP were excluded as follows: for each protocol the median patient dose was calculated. Data that resulted in a calculated patient dose for a given protocol that was larger than five times the median value or smaller than 0.2 times the median value were regarded as a human report error and discarded from further data analysis. Exclusion of these outliers will influence the ratio between maximum and minimum E, but since we believe these to represent report errors, this exclusion may render the per protocol max/min E ratios more representative.

Statistical analysis

Box and whisker plots were used to visualise variations in the radiation dose parameters. These profiles were characterised by five parameters. The central line in the box represents the median value, the edges of the box the 25th percentile (P25) and 75th percentile, and the whiskers the minimum and maximum values. All calculations were performed with Excel 2011 for Mac (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

In the intital practice survey phase, 5,017 studies were used to construct the protocol Top-21. The relative frequency figures of the Top-21 protocols are listed in Table 1. The most frequently performed protocols were brain 23.8 %, abdomen 20.0 %, and thorax-abdomen 9.5 %.

From the 21 participating hospitals with an installed base of 30 scanners, 14 hospitals submitted complete and valid data for 186 standard-sized patients (247 scan phases) on 19 scanners. Each protocol was characterised using data of an average of nine scanners and an average of six hospitals per protocol were used for final analysis of effective CT doses of the 21 CT protocols. Three CT scanners were 4-row, five were 16-row, one was 40-row, eight were 64-row, and two were 128-row. Modern volumetric (3D) tube current modulation techniques were employed in all scanners, except for the four-row models. All image reconstruction was done using filtered back projection techniques.

For the standard-sized patients, the established median DLP and E doses ranged from a low of 105 mGy cm and 0.2 mSv for sinus CT to a high of 1322 mGy cm and 19.4 mSv for multiphasic liver CT (Table 1 and 2). The most frequent examinations were brain, abdomen, and thorax-abdomen CT, which showed a modest median DLP of 814 mGy cm, 567 mGy cm, and 814 mGy cm, and median effective doses of 1.5 mSv, 8.0 mSv, and 11.6 mSv, respectively (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Box plots of the effective dose (mSv) of the three most frequently used CT protocols

The highest doses are observed for multiphasic oncology CT protocols in the abdomen and for evaluation of tumours in the liver and kidney. These were scanned in three to four phases with a median DLP of 1,322 mGy cm and 1,167 mGy cm and corresponding median effective doses of 19.4 mSv and 17.0 mSv. Another relatively dose-intensive CT protocol is the lymphoma staging of the neck, thorax, and abdomen with median DLP of 985 mGy cm and E of 13.8 mSv.

For clinical indications in which contrast media timing is not critical (lymphoma staging), hospitals have decided to split long image ranges into two shorter helical acquisitions. The dose penalty of this practice is limited but variable (Table 2): For imaging of the neck, thorax, and abdomen, the DLP is 1,104 mGy cm when the neck and thorax-abdomen are scanned separately versus 968 mGy cm for the neck-thorax-abdomen scanned in one run. In contrast, for imaging of the thorax and abdomen, the difference is only 790 mGy cm versus 769 mGy cm. Most differences lie in differences in the extra dose from overranging [12, 13]. In contrast, most of the dose increase is seen in imaging of the thorax and liver CT for lung carcinoma staging, with 557 mGy cm for the lung and liver scanned separately versus 383 mGy cm for the thorax-liver in one run. This is due to the fact that for the thorax a lower technique can be chosen.

Ratios between maximum and minimum effective dose ranged between 1.1 and 5.4 for most protocols, which is, although considerably variable between institutions, well within expected ranges seen in another survey [9]. The incidental high figure for the ratio between the minimum and maximum protocol dose can largely be attributed to heterogeneity in examination techniques, such as when helical vs. sequential HRCT of the lungs are considered together as one protocol.

Comparison of our data with other CT dose surveys is given in Table 3. Doses are lower than established in the German survey from 2001 [6] and of comparable value to the results from the two most recent UK surveys [8, 9]. Additionally, when compared to older Dutch data [5], all categories showed similar median values but lower mean values.

Table 3.

Selected dose results of the national survey on radiation dose in CT and comparison with other studies

| Protocol name | NSRD 2010 DLP (mGycm) | NSRD 2010 E103 (mSv) | Brix 2002; DLP (mGycm) | Brix 2002 E60 (mSv) | NRPB 2003 E60 (mGycm) | HPA 2008 E103 (mSv) | DP 2004 E60 (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | 813.7 | 1.5 | 1,016 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Sinus | 105.7 | 0.2 | 283 | 0.8 | – | – | 0.2 |

| Neck | 329.9 | 1.7 | 302 | 2.0 | – | 3.0 | – |

| Thorax | 320.0 | 4.6 | 350 | 5.7 | – | 6.6 | 5.4 |

| Thorax-liver | 542.0 | 8.1 | – | – | 6.8 | 7.0 | – |

| Thorax–abdomen | 813.8 | 11.6 | 1,027 | 17.8 | 10.0 | 10.0 | – |

| Thorax HR | 142.8 | 2.1 | – | – | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Abdomen | 567.0 | 8.0 | 790 | 14.4 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 7.7 |

| Abdomen low dose | 301.6 | 4.5 | – | – | – | 5.5 | 5.8 |

| CT Urography | 708.0 | 10.0 | – | – | – | 25.0 | – |

| Liver multiphasic | 1,322.2 | 19.4 | – | – | – | 14.0 | – |

| CT coronary angio | 516.5 | 13.5 | 583 | 10.5 | – | 16.0 | – |

| CT pulmonary angio | 291.5 | 4.2 | 310 | 5.4 | – | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| CTA abdominal aorta | 555.5 | 7.8 | 552 | 10.3 | – | 5.2 | – |

| C-Spine | 276.0 | 1.4 | 277 | 2.9 | – | 1.9 | – |

| L-Spine | 308.2 | 4.3 | 445 | 8.1 | – | 6.9 | 4.5 |

| Bony pelvis | 332.0 | 4.3 | 440 | 8.2 | – | 6.0 | – |

The Netherlands Commission on Radiation Dosimetry (NCRD) recently published diagnostic reference levels (DRL), including potentially achievable levels after strict dose optimisation [14]. Comparison of our results with Dutch and other European DRLs [8, 15–17] is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

P75 dose results of this study compared to adult DRL in CT across Europe and Canada

| Protocol name | NSRD P75 DLP (mGy cm) | NL 2012 DRL DLP (mGycm) | NL 2012 achievable DLP (mGycm) | F 2011 DRL DLP (mGycm) | D 2010 DRL DLP (mGycm) | UK 2003 DRL DLP (mGycm) | CAN 2005 DRL DLP (mGycm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | 935.6 | – | – | 1,050 | 950 | 930 | 1,300 |

| Sinus | 133.4 | – | – | – | 100 | – | – |

| Thorax | 346.5 | – | – | 475 | 400 | – | 600 |

| Thorax-liver | 608.1 | – | – | – | – | 580 | – |

| Thorax-abdomen | 885.7 | – | – | 1,000 | – | 940 | – |

| Thorax HR | 276.1 | – | – | – | – | 170 | – |

| Abdomen | 618.0 | 700 | 400 | 800 | 900 | 560 | 1,100 |

| CT coronary angio | 671.4 | 1,000 | 300* | – | – | – | – |

| CT pulmonary angio | 371.0 | 350 | 200 | – | – | – | – |

| L-Spine | 405.5 | – | – | 700 | 500 | – | – |

| Bony pelvis | 382.1 | – | – | – | 450 | – | – |

Discussion

The dosimetric results of this survey represent the clinical application of modern multidetector CT in the Netherlands. Compared to surrounding countries, relatively moderate doses are delivered for the most frequently performed CT examinations. This has not substantially changed compared to the Demonstration Project, which recorded data in 2001–2004 [5].

In contrast to other surveys (except the one in Germany [6]), we decided to gain data on a more specific level so that after data analysis we could give focussed feedback to the participating radiology departments. In the Netherlands many Radiology Information Systems only record billing codes (much fewer in number than the clinical scan protocols in practical use), and therefore asking detailed questions resulted in a relatively labour-intensive Web survey. In future surveys we hope to make use of dose reports directly from the CT scanners or from Hospital Information Systems.

It is not surprising that multiphasic abdominal tumour protocols generate the highest doses. CT urography (CTU), commonly regarded as dose intensive, was associated with a modest dose since only split-bolus two-phase studies were included. Using the data of CTU and renal cancer staging to estimate a single bolus, three-phase CTU with all phases covering the abdomen and pelvis would deliver a DLP in excess of 1,300 mGy cm.

In studies with similar clinical indications in which contrast medium administration was not critical, the dose effect of splitting long image ranges into two separate helical acquisitions was variable. The higher increase in thorax-liver CT is probably due to the difference in imaging requirements between thorax and liver, whereby a split protocol is better suitable to serve both most adequately. It should be noted that for different clinical indications in which contrast timing is critical, replacing two separate acquisitions with a combined acquisition may not be possible.

Our survey design is most comparable to the German survey by Brix et al. [6]. The doses are lower than in that particular survey for almost all protocols. Compared to the data published by Shrimpton et al. [8] and Wall et al. [9] from the UK, which is one of the countries with the lowest CT doses worldwide, CT doses in the Netherlands are very similar.

It should be taken into account that we used the published E/DLP conversion factors derived using the ICRP-103 weighting factors [11]. Use of ICRP-60 factors would change the results, but the level of change depends on the specific protocol. For equal DLP, head CT protocols would result in a 16 % lower effective dose, neck CT protocols in a 12 % higher effective dose, thorax CT protocols in a 7 % lower effective dose, abdomen CT protocols in an unchanged dose, and pelvic CT protocols in a 30 % higher dose (abdomen-pelvis 14 % higher).

The similarity in the data of this survey compared to its predecessor [5] indicate, however, that during that period the more liberal use of CT and expansion of CT indications have been balanced with newer technology for dose optimisation such as volumetric tube current modulation and interactive collimation to reduce overranging.

Only a few hospitals in this small sample exceed the DLP set as the reference dose level for CT abdomen, but more than 25 % exceed the level set for CT pulmonary angiography. An integral part of this survey was feedback at the protocol level as a counterattack against this variability and lower doses nationwide. The best management strategy for this feedback will be a topic for future study.

Comparison of our data with other CT dose surveys is given in Table 3. Doses are lower than established in the German survey from 2001 [6] and of comparable value to the results from the two most recent UK surveys, published in reports NRPB-W67 [8] and HPA-CRCE-12 [9]. Additionally, when compared to older Dutch data [5], all categories showed similar median values but lower mean values, indicating a trend to improvement in patient doses.

Comparison of the results of the survey with Dutch and other European DRLs [8, 15–17] is given in Table 4. The values of our DLP data are still above the achievable levels set in the Dutch DRL report [14], indicating that the hospitals included in this pilot survey can improve patient dose by optimising their CT protocols and by upgrading to more dose-efficient hardware.

Obviously, the biggest drawback to the survey was the labour intensity of the Web survey for the participating hospitals. Therefore the response to this pilot was relatively limited and only two-thirds of hospitals participated. Second, there was an inherent lack of control of the data because manpower was limited to monitor data submission. While 14 hospitals submitted data, many entries were incomplete or partly invalid and not all hospitals contributed in the same way to all the protocols. Third, use of the effective dose is only defined for subjects with a normal BMI, and our results only apply to normal-sized or mildly obese patients. In slim patients and in patients with severe or malignant obesity, these results may vary proportionally.

In conclusion, in this CT part of the National Radiation Dose Survey, our detailed data show a moderate dose level in CT in comparison with surrounding countries, which has been stable over the past decade. The variability between hospitals indicates that there is still room for optimisation, whereby the details of our data may allow for more practical feedback than possible before.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. No funding was received for this work.

References

- 1.Mettler FA, Jr, Bhargavan M, Faulkner K, Gilley DB, Gray JE, Ibbott GS, et al. Radiologic and nuclear medicine studies in the United States and worldwide: frequency, radiation dose, and comparison with other radiation sources 1950–2007. Radiology. 2009;253:520–531. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532082010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP, Bhargavan M, Lewis R, Mettler FA, Jr, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2071–2077. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, Kim KP, Mahesh M, Gould R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2078–2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.RIVM Information System Medical Exposures. Accessible at: http://www.rivm.nl/ims/root/o2.html. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 5.Teeuwisse W, Geleijns J, Veldkamp W. An interhospital comparison of patient dose based on clinical indications. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1795–1805. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brix G, Nagel HD, Stamm G, Veit R, Lechel U, Griebel J, et al. Radiation exposure in multislice versus single-slice spiral CT: results of nationwide survey. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1979–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1883-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galanski M, Nagel HD, Stamm G. Pediatric CT Exposure Practice in the Federal Republic of Germany. Results of a nationwide survey in 2005/2006. Accessible at: http://www.mh-hannover.de/fileadmin/kliniken/diagnostische_radiologie/download/Report_German_Paed-CT-Survey_2005_06.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 8.Shrimpton PC, Hillier MC, Lewis MA, Dunn M. National survey of doses from CT in the UK: 2003. Br J Rad. 2006;79:968–980. doi: 10.1259/bjr/93277434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart D, Wall BF, Hillier MC, Shrimpton P. Frequency and collective dose for medical and dental X-ray examinations in the UK, 2008. Report HPA-CRCE-012. London, HPA, 2010. Accessible at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/Publications/Radiation/CRCEScientificAndTechnicalReportSeries/HPACRCE012/. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 10.CBS Statline. Database of the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics. Available at: http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=81177NED&D1=13,25,38-42&D2=0-2,4-13,34-38&D3=0&D4=l&HD=110905-0955&HDR=G3,G2,T&STB=G1. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 11.Deak PD, Smal Y, Kalender WA. Multisection CT protocols: sex- and age-specific conversion factors used to determine effective dose from dose-length product. Radiology. 2010;257:158–166. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Molen AJ, Geleijns J. Overranging in multisection CT: quantification and relative contribution to dose—comparison of four 16-section CT scanners. Radiology. 2007;242:208–216. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2421051350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schilham A, van der Molen AJ, Prokop M, de Jong HW. Overranging at multisection CT: an underestimated source of excess radiation exposure. Radiographics. 2010;30:1057–1067. doi: 10.1148/rg.304095167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veldkamp WJH, Becht A, Bouwman RW, et al. Diagnostic reference levels in the Netherlands [in Dutch]. Delft: Nederlandse Commissie voor Stralingsdosimetrie, 2012. Available at: http://www.stralingsdosimetrie.nl/assets/files/ncs_report/NCS%20Rapport%2021%20DRN%20juni%202012.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 15.IRSN. Arrêté de 24 octobre 2011 relatif au niveaux de référence diagnostiques en radiologie et en medécine nucléaire. Available at: http://nrd.irsn.fr/document/site_49/fckfiles/File/Arrete-NRD-24102011.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 16.Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz. Bekantmachung der aktualisierten diagnostischen Referenzwerten für diagnostische und interventionelle Röntgenuntersuchungen. Salzgitter, Bfs, 2010 Available at: http://www.bfs.de/de/ion/medizin/referenzwerte02.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2012

- 17.Aldrich JE, Bilawich AM, Mayo JR. Radiation doses to patients receiving computed tomography examinations in British Columbia. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2006;57:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]