Abstract

Background

Peroneal nerve lesions are not common and are often exclusively assessed clinically and electromyographically.

Methods

On a routine MR examination without dedicated MR-neurography sequences the peroneal nerve can readily be assessed. Axial T1-weighted sequences are especially helpful as they allow a good differentiation between the nerve and the surrounding fat.

Results

The purpose of this article is to review the normal anatomy and pathologic conditions of the peroneal nerve around the knee.

Conclusion

In the first part the variable anatomy of the peroneal nerve around the knee will be emphasized, followed by a discussion of the clinical findings of peroneal neuropathy and general MR signs of denervation. Six anatomical features may predispose to peroneal neuropathy: paucity of epineural tissue, biceps femoris tunnel, bifurcation level, superficial course around the fibula, fibular tunnel and finally the additional nerve branches. In the second part we discuss the different pathologic conditions: accidental and surgical trauma, and intraneural and extraneural compressive lesions.

Teaching Points

• Six anatomical features contribute to the vulnerability of the peroneal nerve around the knee.

• MR signs of muscle denervation within the anterior compartment are important secondary signs for evaluation of the peroneal nerve.

• The most common lesions of the peroneal nerve are traumatic or compressive.

• Intraneural ganglia originate from the proximal tibiofibular joint.

• Axial T1-weighted images are the best sequence to visualise the peroneal nerve on routine MRI.

Keywords: MR, Peroneal nerve, Denervation, Knee, Proximal tibiofibular joint, Intraneural ganglion

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee joint has become a very important imaging tool for assessment of knee pain in daily routine. Most clinical inquiries are about menisci, cartilage or ligaments of the knee joint. Peroneal nerve lesions are rather uncommon and are usually exclusively evaluated by clinical and/or electrophysiological examination. Because MRI provides exquisite soft tissue detail, the peroneal nerve can often be well visualised, even on routine MR sequences. In most centres, a combination of coronal, sagittal, axial fat-suppressed intermediate weighted sequences and a sagittal T1-weighted sequence is used for routine imaging of the knee. Adding an axial T1-weighted sequence (WI) may be helpful in evaluation of the course of the peroneal nerve branches and may enhance the conspicuity for peroneal nerve lesions. It should be considered as a first step in case of a suspected peroneal nerve lesion. Specific MR neurography sequences have shown their utility for evaluation of peripheral nerves and can be used for a more complete workup, at both 1.5 and 3 T [1]. The purpose of this paper is, however, to emphasise the strength of meticulous analysis of routine MR sequences in the diagnosis of peroneal nerve lesions about the knee. In the first part we focus on the relevant anatomy of the peroneal nerve and general clinical and MR features of peroneal neuropathy. Electromyography is only briefly addressed, as this is beyond the scope of this pictorial review.

In the second part we present the most common lesions involving the peroneal nerve around the knee.

Anatomic background

The common peroneal nerve is the lateral division of the sciatic nerve. It courses from the posterolateral side of the knee around the biceps femoris tendon and the fibular head to the anterolateral side of the lower leg. Its relationship to the most important landmarks is illustrated on Fig. 1. On MRI the peroneal nerve and its branches can most easily be identified on axial T1-WI as small bundles of fascicles cushioned in surrounding fatty tissue (Fig. 1c, d, e and f).

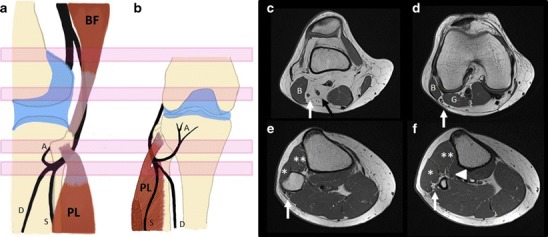

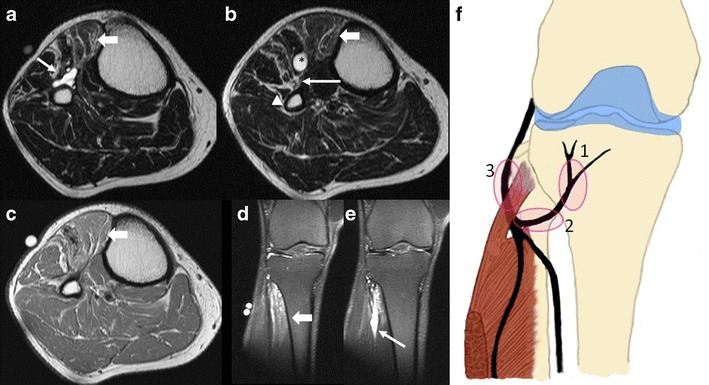

Fig. 1.

Normal anatomy of the peroneal nerve at the level of the posterolateral corner of the right knee. Schematic drawing of a sagittal (a) and coronal (b) view with corresponding axial T1-WI of a right knee; the levels are indicated by the transparent boxes. On the schematic drawing the nerve is seen branching off the sciatic nerve, turning around the biceps femoris muscle (BF), passing through the peroneal tunnel between the insertion of the peroneus longus muscle (PL) and the fibula. As it exits the tunnel, it trifurcates in a deep (D) and superficial peroneal nerve (S) and a recurrent or articular branch (A). The articular branch is the entrance port for intraneural ganglia originating from the proximal tibiofibular joint (see the section on intraneural ganglia). Axial T1-WI at the level of the distal femur (c) shows the common peroneal nerve (white arrow) and the tibial nerve (black arrow) as they branch off the sciatic nerve. Note the intimate relationship of the common peroneal nerve with the medial side of the biceps femoris muscle (B). Axial T1-WI at the level of the femoral condyles (d) shows the common peroneal nerve (white arrow) between the short head of the biceps femoris (B) and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle (G), a site of possible entrapment in case of variant course of the short head of the biceps femoris. The fascicles of the deep and superficial peroneal nerve can sometimes be discerned from this level on, the former more anteriorly, the latter more posteriorly, corresponding to the location of the anterior and lateral compartment of the lower leg. Axial T1-WI at the level of the fibular head (e). The common peroneal nerve (white arrow) is found posteriorly and can be traced by the fat around it. The peroneus longus (*) and anterior tibial muscle (**) are already seen at the most proximal parts of the lateral and anterior compartments. Axial T1-WI at the level just below the fibular neck (f) shows the superficial and deep peroneal nerve (white arrow). Because of their more horizontal course at this level, they are more difficult to discern from each other. At the 12 o’clock position the articular branch can be visualised as a small black dot surrounded by hyperintense fat (arrowhead). a adapted with permission from ref [50]. b adapted with permission from ref [10]

The peroneal nerve has several unique anatomical features making it susceptible to injury.

The first is the relative paucity of epineural supporting tissue, rendering the nerve more susceptible to compression [2–5].

The second consists of a variant of its course along the distal biceps femoris muscle. A tunnel can be formed between the biceps femoris muscle and the lateral gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 2). This occurs when there is a more posterior or distal extension of the short head of the biceps femoris muscle and, rarely, when there is a more distal extension of the long head of the biceps femoris muscle. This tunnel results in less fatty cushioning of the peroneal nerve and is considered a predisposing factor for neuropathy [6].

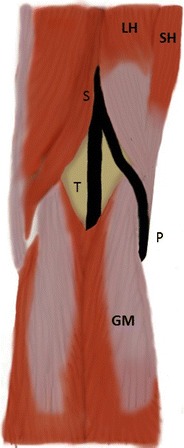

Fig. 2.

Schematic drawing of the popliteal fossa (right knee). A tunnel can be formed between the short head of the biceps femoris (SH) and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle (GM). Long head of the biceps femoris muscle (LH), sciatic nerve (S), tibial nerve (T) and peroneal nerve (P). Adapted with permission from ref [50]

A third feature is a more proximal bifurcation of the peroneal nerve (Fig. 3). This is found in 10 % of preserved specimens and makes the peroneal nerve more prone to injury with arthroscopic inside-out lateral meniscal repair [7, 8].

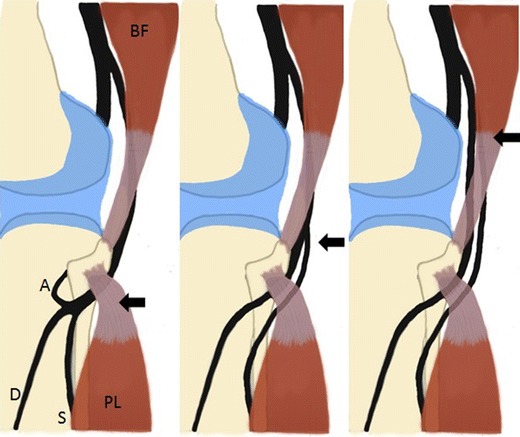

Fig. 3.

Schematic drawing showing the variations at the level of bifurcation (thick black arrow) of the common peroneal nerve. In about 81 % of the people the bifurcation of the common peroneal nerve occurs at or below the level of the fibular neck (a). In about 9 % the peroneal nerve bifurcates between the fibular neck and the knee joint (b). In about 10 % bifurcation occurs above the knee joint line (c)

The fourth feature is the superficial course of the peroneal nerve around the fibular neck, where it can be compressed or stretched in case of trauma (Fig. 1).

The fifth feature is the fibular tunnel is formed between the musculo-aponeurotic arch of the peroneus longus and soleus tendon and the bony floor of the proximal fibula (Fig. 1). Entrapment or impingement in this tunnel occurs mainly between the fibres of the peroneus longus and the fibular neck and is typically exacerbated by forced inversion of the foot, stretching the peroneal nerve [5, 9, 10]. The osteofibrous tunnel between the peroneus longus muscle and the fibula can be tightened by an ossification at the peroneus longus muscle origin or tug lesion (Fig. 4). It should be considered when peroneal nerve neuropathy is present clinically without any other obvious cause. A peroneal tug lesion typically occurs on the lateral side of the fibula, while a soleus tug lesion occurs on the medial side [11, 12]. The typical location allows differentiation with an osteochondroma [11].

Fig. 4.

Tug lesion in the peroneus longus tendon. Plain radiography of the right knee, anteroposterior (a) and lateral view (b) demonstrate an extra ossification at the lateral side of the proximal fibula (arrows). This most likely corresponds to the origin of the peroneus longus tendon. It can cause tenderness over the peroneal tunnel and hypoesthesia and muscle weakness in the areas innervated by the peroneal nerve

The sixth and last feature is the additional branches at the level of the knee joint. The most important is the articular branch (also called recurrent branch). When exiting the fibular tunnel the peroneal nerve typically trifurcates in the deep and superficial peroneal nerve and a smaller articular branch (Fig. 1). This articular branch provides sensory information from the proximal tibiofibular joint and has been shown to be a very common location and entrance port for intraneural ganglia [13]. In addition to the articular branch, the lateral sural cutaneous nerve and the peroneal communicating branch, a small cutaneous branch that originates from the common peroneal nerve, about 11 mm above the joint line, is also described, and this may explain anecdotal cases of postoperative dysesthesia on the lateral side of the knee [8]. This small branch is too small to discern on conventional MR imaging, unless there is pathological enlargement.

The two other branches of the common peroneal nerve, the deep and superficial peroneal nerve, respectively innervate the anterior and lateral compartment of the lower leg (Fig. 5). The superficial peroneal nerve provides motor innervation to the muscles of the lateral compartment, the peroneus longus and brevis muscle. Sensory innervation is provided to the anterolateral side of the lower leg, where the nerve pierces the crural fascia, and to the dorsum of the foot. The deep peroneal nerve provides motor innervation to the four muscles of the anterior compartment: the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum, extensor hallucis longus and peroneus tertius muscle. The tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum muscle are almost always visible on the most caudal slices of the knee on MR imaging.

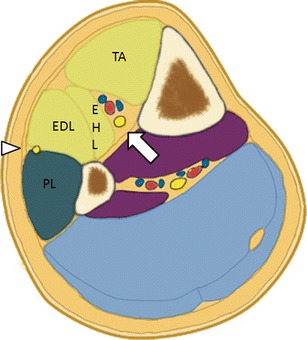

Fig. 5.

Schematic drawing of a cross section of the right lower leg. The anterior compartment contains the anterior tibial muscle (TA), extensor hallucis longus muscle (EHL) and the extensor digitorum longus muscle (EDL). The neurovascular bundle, comprising the deep peroneal nerve (arrow), runs between anterior tibial muscle and extensor hallucis longus muscle. The lateral compartment contains the peroneus longus muscle at this level. The superficial peroneal nerve (arrowhead) courses anteriorly in the lateral compartment along the intermuscular septum between the anterior and lateral compartments

Clinical findings range from pain over the fibular neck radiating into the peripheral distributions to dorsiflexion and eversion weakness and, in the most severe cases, in frank dropfoot. Patients with diabetes mellitus are predisposed to entrapment neuropathies because of a lower microvascular ischaemia threshold. Coexistent foot inversion weakness suggests a sciatic nerve lesion or L5 radiculopathy. Weakness in the biceps femoris muscle also suggests a more proximal lesion, as this is the only muscle that is innervated by the peroneal nerve above the knee.

Electrophysiological tests are commonly performed, and they are an important aid in differentiating a peroneal neuropathy from a more proximal lesion or an L5 radiculopathy [5]. There are several limitations to electrophysiological testing. It is hard to evaluate deeply located muscles, and these tests are relatively invasive, operator dependent, do not pick up denervation in the earliest phase and do not allow a complete evaluation of a muscle.

General imaging features of denervation

The muscles of the anterior and lateral compartment are in close proximity to the knee. This provides additional information that is easily available to evaluate potential denervation of the peroneal nerve.

Three denervation patterns can be differentiated, but on imaging there is considerable overlap with different patterns occurring at the same time. The first is oedema, corresponding to the acute phase. In experimental settings hyperintense changes are visible on short tau inversion recovery (STIR) after 24 h and on fat-suppressed T2-WI after 48 h, but are generally considered equally sensitive for detection of oedema after 48 h [14–16] (Figs. 6 and 7). The two other denervation patterns occur later, unless nerve conduction has been restored. The second pattern is atrophy, corresponding to loss of muscle tissue, and it occurs after 7 days [16]. It can be visualised on all imaging sequences and it is reversible. The last pattern is fatty replacement of the muscle. This suggests long-standing denervation (several weeks to months) and indicates the end stage of denervation in which the involved muscle fibres are inevitably lost. Fatty replacement is best visualised on axial non-fat suppressed T1-WI [16, 17] (Fig. 8). Usually the entire muscle is affected, but in cases of partial denervation or collateral motor innervation, changes may be delayed or absent.

Fig. 6.

Acute denervation in the anterior compartment. Axial T2-WI showing diffuse hyperintense signal in the tibialis anterior muscle (arrow) and extensor digitorum muscle of the right lower leg (arrowhead). A hyperintense cystic structure is visualised along the course of the superficial (thick arrow) and deep peroneal nerve (curved arrow), in keeping with an intraneural ganglion cyst

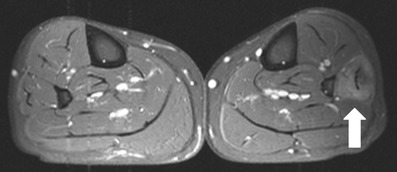

Fig. 7.

Acute denervation in the lateral compartment. Axial fat-suppressed T2-WI shows diffuse hyperintense signal in the peroneus longus muscle (white arrow) of the left lower leg. In the absence of neuropathy, lateral compartment syndrome must be mentioned in the report, as this entity often goes unrecognised clinically in case of minor or absent trauma

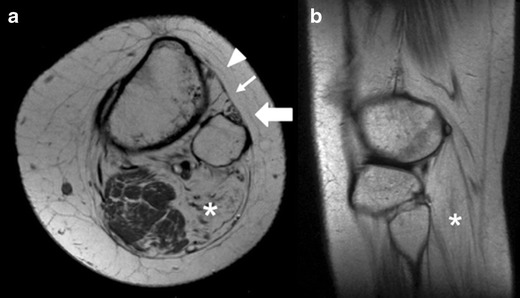

Fig. 8.

Chronic muscle denervation. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T1-WIs show fatty replacement and atrophy in the tibialis anterior muscle (arrowhead), extensor digitorum longus muscle (thin arrow) and peroneus longus muscle (thick arrow) of the left lower leg. There is also prominent fatty replacement and atrophy in the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle (asterisk). Previously this patient underwent a resection of a schwannoma at a more proximal level in the sciatic nerve

In long-standing denervation MR is a powerful tool in the differentiation between fatty replaced muscle and muscle at continued risk to develop fatty replacement [16]. This is important information for the surgeon as fatty replaced muscle is highly unlikely to recover after surgical nerve repair and it is also a major benefit of MR over electromyography.

Spectrum of pathologic conditions

The spectrum of pathologic conditions can be divided into two categories. Traumatic lesions, including surgical injury, range from relatively minor direct compressive trauma to major fracture dislocation. Compressive lesions are the last and most heterogeneous category, which occur either extraneurally or intraneurally.

Traumatic lesions

Traumatic lesions are the most common lesion of the peroneal nerve. The peroneal nerve, as discussed earlier, is prone to traumatic or surgical injury because of its superficial course and its paucity of epineural supporting tissue. Many of these injuries to the peroneal nerve are evident clinically or on electromyography and will not require imaging other than conventional X-rays for evaluation of bony trauma. Three basic mechanisms are involved in traumatic peroneal nerve injury: traction, contusion and penetrating trauma. These mechanisms often coexist and differentiation amongst them is not always feasible clinically [18].

Traction injuries

Traction or stretching injuries of the peroneal nerve can occur following ankle inversion trauma, high-grade varus sprains of the knee, proximal fibular fractures, posterolateral corner knee injury or dislocation of the knee. The greater the extent of damage to the bony and ligamentous structures, the more likely is damage to the peroneal nerve. A complete rupture of the nerve is most commonly found in case of dislocation with disruption of both the cruciate ligaments and posterolateral corner [19, 20]. Peroneal nerve palsy may also be associated with the placement of oblique locking screws [21].

Contusion

Contusion almost always results from direct impact, which may occur in football or contact sports. This results in a compression of the peroneal nerve against the proximal fibula. Patients present with lateral knee pain and signs of sensory or motor disturbance in the peroneal nerve area.

The nerve will appear thickened and oedematous, resulting in a hyperintense signal on the T2-WI and hypointense signal on the T1-WI (Fig. 9). Even in the absence of a clear history of trauma, oedema in the proximal fibula and the muscles of the lateral compartment should alert the radiologist to a potential associated lesion of the peroneal nerve.

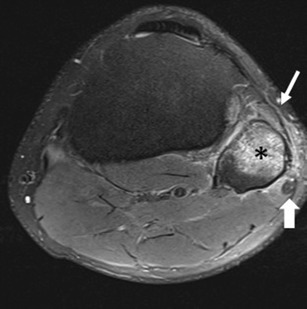

Fig. 9.

Posttraumatic contusion of the peroneal nerve occurring after a direct trauma on the lateral compartment of the left knee. Axial fat-suppressed T2-WI shows a thickened peroneal nerve (thick arrow) and hyperintense oedema in the surrounding subcutaneous tissues, the fibular head (asterisk) and the peroneus longus muscle (thin arrow).

Penetrating trauma

Penetrating wounds can result in a complete or partial disruption of the nerve fascicles. If the nerve sheath is disrupted and the fascicles are separated, the regenerating nerve fascicles and Schwann cells will sprout randomly, creating a terminal ‘neuroma’ or stump neuroma [18]. Spindle or lateral neuromas occur when the nerve sheath is partially or fully intact [22]. They occur distally from the damaged nerve ending and represent a local response to the trauma with fusiform or lateral thickening (Fig. 10).

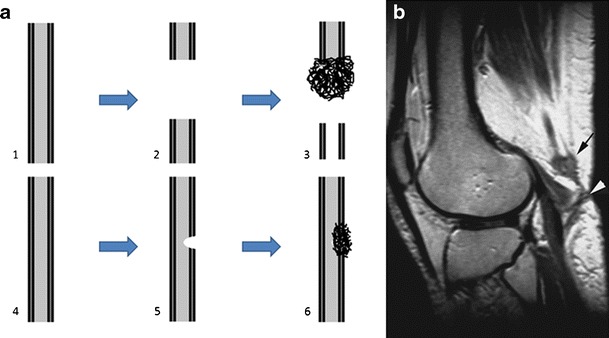

Fig. 10.

Neuroma. Schematic drawing (a) showing the two types of nerve damage. A normal nerve (1 and 4) is surrounded by a nerve sheath on both sides. A complete disruption of the nerve (2) results in disorganised sprouting of nerve fascicles and fibrous tissue (3). This creates a ‘ballon-on-a-string’ or ‘green-onion’ image, typical of a terminal (posttraumatic) neuroma. Wallerian degeneration occurs distally in the nerve. A partial laceration of the nerve (5) causes focal regeneration with hypertrophy of the nerve fascicles and fibrosis. This creates a focal asymmetrical thickening on imaging (6). Sagittal T2-WI image (b) shows a hypointense terminal neuroma (black arrow) after accidental surgical transection of the peroneal nerve. Note also associated hypointense strands of scar tissue (white arrowhead) in the adjacent subcutaneous fat

A terminal ‘neuroma’ or posttraumatic neuroma has a bulbous appearance from the tangle of fascicles, Schwann cells and associated fibrosis. It has low signal intensity on T1-WI and intermediate to high signal intensity on T2-WI. It demonstrates variable enhancement after administration of gadolinium contrast. A peripheral rim of low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images has been reported as well [22]. Surgical clips or metallic fragments may cause artefacts. The image of the proximal nerve terminating in such a posttraumatic neuroma is sometimes referred to as a ‘balloon-on-a-string’ or ‘green-onion’ appearance [23]. Posttraumatic neuromas may resemble true neurogenic tumours, such as schwannomas or neurofibromas, but a split fat sign or target sign is absent (see section on peripheral nerve sheath tumours). In addition, any surrounding scar tissue suggests a traumatic context [23].

In centres where arthroscopic meniscal repair is performed, the peroneal nerve can be captured or tethered within the sutures when the inside-out technique is used. This occurs more easily if the bifurcation of the peroneal nerve occurs at a level proximal to the fibular neck (Fig. 3). The use of a posterior incision and a retractor is reported to prevent this injury [8]. In addition, trauma to a cutaneous branch originating from the common peroneal nerve 11 mm above the joint may explain anecdotal cases of previously unexplained local dysesthesia on the lateral side of the knee [8].

Miscellaneous traumatic lesions

A typical case consists of a compartment syndrome of the anterior compartment occurring after minor trauma [9]. The compartment syndrome is initiated by a vicious cycle of oedema and venous obstruction causing compression of the muscles and the deep peroneal nerve. In rare cases an isolated compartment syndrome of the lateral compartment after minor injury can occur [24, 25]. Partial recovery of the peroneal nerve function can occur, though sensory disturbances are usually persistent. A chronic sequel of unrecognised compartment syndrome is calcific myonecrosis [26]. This can occur 10 to 64 years after the initial trauma. The clue to the diagnosis is the history of a remote trauma and the plaque-like calcifications on plain radiographs, oriented along the course of the muscle fibres.

The most subtle trauma that can cause denervation of the peroneal nerve is a closed deglovement injury, also known as a Morel-Lavallée lesion. Deglovement implies a shearing between the fascia and the subcutaneous tissues. This creates a potential space that fills up with serosanguinous fluid ranging from clear fluid to frank blood. A subcutaneous sensory branch passing through the fascia can be lacerated resulting in local hypoesthesia, as can happen to the superficial peroneal nerve in the lower third of the lateral compartment. On T1-WI it may appear hyperintense because of the methaemoglobin content [27]. It may contain fluid-fluid levels resulting from sedimentation of blood components and occasionally entrapped fat globules may be present [28]. An inflammatory reaction commonly creates a peripheral capsule. This capsule appears hypointense on all imaging sequences and may show some patchy enhancement [27]. The location of the lesion and the history of trauma often suggest the diagnosis, although there may be a remote history of trauma (3 months up to 34 years). This may sometimes cause confusion with a soft tissue tumour, especially if the lesion has evolved to a chronic organising haematoma with heterogeneous signal on T2-WI and patchy internal enhancement [28].

Sequelae of trauma can lead to chronic compression of adjacent nerves. Displaced bone fragments and heterotopic ossification are easily visualised on plain radiographs [22]. Previously undetected fractures can cause internal joint derangements, which in turn lead to joint effusions and sometimes large synovial cysts compressing periarticular tissues and nerves.

Intraneural compressive lesions

Intraneural ganglia

Intraneural ganglia are relatively rare compared to extraneural ganglia, but they should be considered in case of unexplained foot drop [29]. Clinical and electromyographic findings are almost always more pronounced compared with extraneural ganglia, and this is related to the perineurium that restricts expansion of the intraneural ganglion and thus increases the pressure on the nerve.

The peroneal nerve is the most common location for intraneural ganglion cysts. An articular origin is becoming increasingly evident and has been demonstrated by delayed MR arthrography [30]. The presence of the articular branch explains the high incidence of this condition at the peroneal nerve. This branch serves as a conduit for fluid, dissecting the epineurium between the fascicles. Intraneural ganglia follow the path of the least resistance and extend proximally in the deep peroneal nerve, the common peroneal nerve and sometimes even in the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve. Cases reporting bilateral occurrence [31] in children [32] and in both peroneal and tibial nerves [33] have been described. Surgical intervention must also address the proximal tibiofibular joint to avoid recurrence [34].

On imaging intraneural ganglia appear as tubular structures contained within the nerve, with a hyperintense signal on T2-WI (Fig. 11) and a hypointense signal on T1-WI. They have no capsule and show no enhancement after administration of gadolinium contrast. A case has been reported in which there was some, mostly peripheral enhancement; this may lead to confusion with a cystic schwannoma [38].

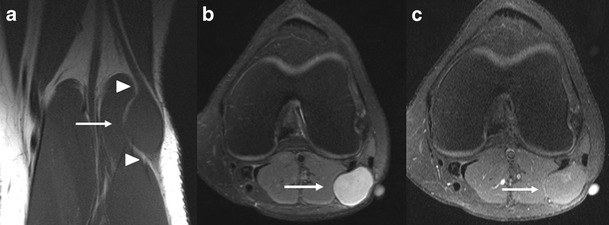

Fig. 11.

Recurrent intraneural ganglion. Axial T2-WI at the level of the right fibular neck (a) shows the horizontal part of the recurrent articular branch at the 12 o’clock position. The level just below (b) shows extension of the cyst in close relationship with the deep peroneal nerve (arrow), situated between the cyst and the fibular neck. More laterally the superficial peroneal nerve can be discerned (arrowhead). On both images the signal intensity of the anterior tibial muscle (thick arrow) is slightly higher when compared to the surrounding muscles. Axial T1-WI (c) shows no significant fatty infiltration in the anterior compartment. Coronal fat-suppressed T2 PD-WI (d) shows a hyperintense signal in the most proximal part of the anterior tibial muscle (thick arrow), in keeping with denervation oedema. The second, more posterior coronal fat-suppressed T2 PD-WI (e) shows the hyperintense ganglion (thin arrow) with a slightly beaded appearance along the course of the deep peroneal nerve. Irritation of the peroneal nerve by the ganglion was confirmed on the EMG. The ganglion was surgically drained and curettage of the proximal tibiofibular joint was performed. Schematic drawing (f) showing the sites where the typical signs of an intraneural ganglion can be observed. The ascending part of the articular branch is the location of the tail sign (1); the transverse limb sign can be observed on the horizontal part of the articular branch (2). When the intraneural ganglion extends proximally in the common peroneal nerve a signet ring sign can be observed (3)

Three additional signs have been described to aid in the diagnosis on axial imaging (Fig. 11). The tail sign indicates the cyst’s origin anterior to the proximal tibiofibular joint on the course of the ascending part of the articular branch. On adjacent slices on a lower level, the transverse limb sign indicates the horizontal cyst extension within the articular branch. Finally, usually on the same image as the tail sign, the signet ring sign indicates the cyst extending within the common peroneal nerve, displacing the nerve to the periphery. This creates an image of a ring (the cyst) with a signet (the peripherally displaced nerve) [35].

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours

Three main histological types can be distinguished. Schwannoma (also known as neurilemmoma) and the neurofibroma are the benign forms. The malignant counterpart is the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST).

Schwannomas are slow-growing encapsulated tumours that can be separated surgically from the parent nerve. Occasionally in large or long-standing schwannomas intralesional degeneration with fibrosis, haemorrhage, calcification and cystic necrosis occurs, leading to a so-called ancient schwannoma [36, 37]. In case of an elongated cystic mass along the peroneal nerve, an intraneural ganglion is a more likely diagnosis [38].

Neurofibromas are intimately associated with the nerve and cannot be separated. The vast majority of neurofibromas are localised and not associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) [36].

Schwannomas and neurofibromas cannot be definitely differentiated on imaging (Fig. 12). Typical imaging findings are a fusiform shape, the nerve entering proximally and exiting distally and a split-fat sign, representing the normal fat around a neurovascular bundle. A well-defined margin and the presence of the split-fat sign suggest benignity [39]. Some features that can aid in the differentiation are described in Table 1 [40].

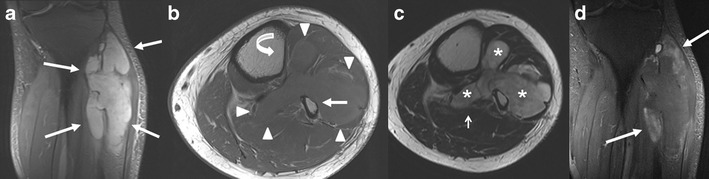

Fig. 12.

a-c Schwannoma of the left common peroneal nerve. Coronal T1-WI (a) showing a spindle shaped lesion (arrow) in the common peroneal nerve at the level of the lateral femoral condyle, with a signal that is isointense to the surrounding muscle. The peroneal nerve is seen entering proximally and exiting distally (arrowheads). A split-fat sign is visualised around the lesion. Axial fat-suppressed T2-WI (b) shows a homogeneous hyperintense signal (arrow). Axial fat-suppressed T1-WI after IV administration of gadolinium contrast (c) shows almost no enhancement (arrow)

Table 1.

Differentiating features for peripheral nerve sheath tumours

| Schwannoma-specific features | Neurofibroma-specific features | Non-specific features benign PNST | Malignant PNST |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripherally or centrally entering and exiting nerve | Size >5 cm | ||

| Fascicular appearance on T2-WI | Cystic areas On T2-WI | Heterogeneous appearance on T2-WI and T1-WI | |

| Thin hyperintense rim on T2-WI | Target sign on T2-WI | Infiltrative margin | |

| Diffuse enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-WI | Central enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-WI | Peripheral enhancement on fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced T1-WI | Heterogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-WI |

Fascicular appearance: multiple small ringlike structures (with peripheral higher signal intensity) on axial T2-WI or intermediate-WI

Thin hyperintense rim: rim is less than one quarter of the diameter of the lesion

Target sign: a central hypointense focus with a peripheral hyperintense rim on T2-WI, the central focus making up less than three quarters of the diameter of the lesion

MPNSTs represent about 6 % of malignant soft tissue tumours [41]. There is a strong association with NF-1, but only 5 % of patients with NF-1 develop MPNST. They typically occur in major nerve trunks and histologically they are indistinguishable from soft tissue fibrosarcoma. Clinical signs of malignant degeneration of a neurofibroma are non-specific [36]. If imaging suggests an aggressive lesion, biopsy should immediately be performed to exclude malignant transformation [41].

MPNSTs are heterogeneous on both T1-WI and T2-WI and after contrast administration, with dark areas corresponding to calcifications and hyperintense areas on T2-WI to central necrosis. Three imaging signs are suggestive of a MPNST: size more than 5 cm (the average size of neurofibroma [42, 43]), heterogeneous appearance due to intratumoral bleeding and areas of necrosis [36, 42] and infiltrative margin [43]. Atypical presentation can occur and any other sarcoma may mimic a MPNST (Figs. 13 and 14). Myxoid tumours may mimic cystic lesions. If there is any suspicion of a malignant lesion, intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast should be performed. True cystic lesions will only show minor peripheral rim enhancement, whereas a heterogeneous enhancement pattern is seen in myxoid or malignant tumours with cystic areas [44].

Fig. 13.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour with atypical features. This patient presented with a painful swelling on the lateral side of the right leg. The initial diagnosis after biopsy was a benign cystic lesion. Coronal T1-WI (a) showing a lesion with a signal intensity almost isointense to the surrounding muscle (arrow). Axial fat-suppressed PD WI (b) shows almost homogeneous hyperintense signal (arrow) in the lesion with a thin hypointense rim. Axial T1-WI (c) after IV administration of gadolinium shows absence of enhancement (arrow). EMG was not performed in this case, as the diagnosis of a malignant PNST was confirmed histologically and the nerve would certainly be sacrificed during surgery. The sometimes misleading cystic appearance of soft tissue tumours is discussed in more detail in the text

Fig. 14.

Myxoid liposarcoma compressing the peroneal nerve. Because the patient had café au lait spots, a diagnosis of a malignant PNST in a patient with NF1 was initially proposed, with the request for pathological confirmation. Coronal fat-suppressed PD T2-WI (a) shows a polylobulated homogenously hyperintense mass (thin arrows) mostly located in the lateral compartment of the left lower leg, larger than 5 cm. Axial T1-WI (b) shows the mass (arrowheads) extending in the anterior, lateral and deep posterior compartment. Note scalloping on the anterior side of the fibula (thick arrow) and the lateral side of the tibia (curved arrow). Axial T2-WI (c) shows a heterogeneous mostly hyperintense signal in the mass (asterisk), clearly delineating it from the surrounding muscle. There is no fat plane between the soleus muscle and the superficial posterior compartment (arrow), strongly suggesting extension in all four compartments of the lower leg. No muscle oedema is present. Coronal fat-suppressed T1-WI after IV administration of gadolinium contrast (d) shows inhomogeneous peripheral enhancement of the mass (arrows)

Extraneural compressive lesions

Osteochondroma

A less common cause of extrinsic compression is an osteochondroma. These are developmental lesions rather than true neoplasms and are also referred to as an osteocartilaginous exostosis, cartilaginous exostosis or simply exostosis. Continuity with the underlying native bone cortex and medullary canal is pathognomonic of osteochondroma and is easily recognised on plain radiographs [45]. The most common location for solitary exostoses is the metaphysis of the distal femur, the proximal tibia or the proximal humerus [46]. Hereditary multiple exostoses, an autosomal dominant syndrome, is more often associated with complications, mainly due to the mass effect on adjacent structures [47]. Neurologic compression occurs most commonly at the peroneal nerve [48].

On imaging a sessile and a pedunculated type can be differentiated. Bony structures can be evaluated on conventional X-rays, but MR imaging demonstrates a better extent of cortical and medullary continuity between the cartilaginous exostosis and the parent bone (Fig. 15). In cases of neurologic compromise the cartilaginous exostosis may exert a mass effect in the expected nerve location, but the nerve itself may be too small to discern. Signs of denervation in the dependent muscles strongly suggest neural compression or entrapment.

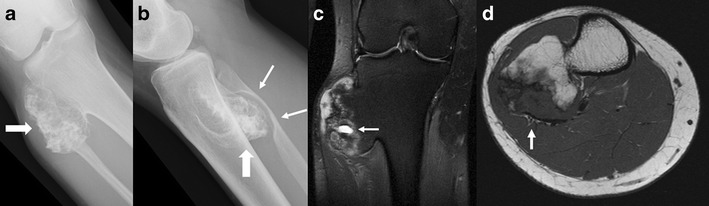

Fig. 15.

Large osteochondroma. Plain radiographs. Anteroposterior (a) and lateral view (b) demonstrate a large sessile osteochondroma (thick arrow) at the lateral aspect of the right tibia. There is obvious scalloping (arrow) and slight posterior displacement of the fibula, in keeping with a slow-growing lesion. Coronal fat-suppressed T2-WI (c) shows a hyperintense cartilage cap with partially mineralised hypointense cartilage and an intralesional cystic component (arrow). The maximum cartilage thickness is 16 mm. Axial T1-WI (d) shows the posterior displacement of the common peroneal nerve with a preserved fascicular structure (thick arrow)

Extraneural ganglia

Extraneural ganglia originating from the proximal tibiofibular joint are more frequent than their intraneural counterpart. These cystic masses can sometimes be very large and they are connected to the proximal tibiofibular joint with a fine stalk. Articular connection has been demonstrated by delayed arthrography, with best results on computed tomography (CT) 1–2 h post injection [49]. The most common location is in the tibialis anterior muscle and the peroneus longus muscle [50]. Pressure on the peroneal nerve can occur (Fig. 16), leading to hypoesthesia or dorsiflexion weakness.

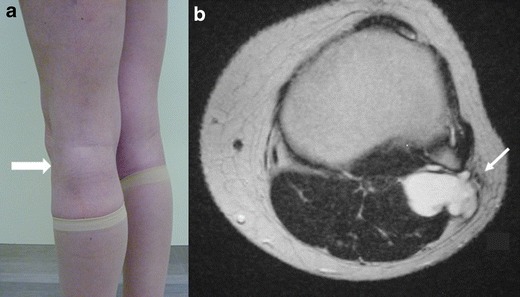

Fig. 16.

Extraneural ganglion. Photograph of the left knee (a) shows a focal swelling on the posterolateral corner of the knee (thick arrow). Axial T2-WI (b) shows a cyst posterior to the proximal tibiofibular joint, displacing the common peroneal nerve laterally (arrow)

Anecdotal reports exist on a compartment syndrome caused by an extraneural ganglion, both in the anterior and lateral compartment [51, 52].

Their imaging appearance is similar to other cystic structures, consisting of a hypointense signal on T1-WI, a hyperintense signal on T2-WI and a thin hypointense wall that enhances after administration of gadolinium contrast. Sometimes internal septa may be present.

Conclusion

Peroneal nerve lesions are relatively uncommon lesions. Most are of traumatic aetiology, but ganglia, peripheral nerve sheath tumours and osteochondroma should also be considered. Identification and characterisation of these lesions may be done on routine MR sequences, particularly if an axial T1-weighted sequence is included in the imaging protocol. Careful revision of clinical history, clinical examination, electromyographic findings, previous imaging findings and consideration of the specific anatomical features help the radiologist to suggest a specific diagnosis or to narrow down the differential diagnosis. It will also help to suggest further imaging with dedicated MR neurography protocols and whether biopsy should be performed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. M. Kunnen and M. Duyts for their assistance in preparing some of the illustrations.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this work.

References

- 1.Chhabra A, Lee PP, Bizzell C, Soldatos T. 3 Tesla MR neurography–technique, interpretation, and pitfalls. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40(10):1249–60. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunderland S. The intraneural topography of the sciatic nerve and its popliteal divisions in man. Brain. 1948;71:242–273. doi: 10.1093/brain/71.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunderland S, Bradley K. The cross-sectional area of peripheral nerve trunks devoted to nerve fibres. Brain. 1949;72:428–449. doi: 10.1093/brain/72.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunderland S. The connective tissues of peripheral nerves. Brain. 1965;88:841–854. doi: 10.1093/brain/88.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toussaint CP, Perry EC, 3rd, Pisansky MT, Anderson DE. What’s new in the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral nerve entrapment neuropathies. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(4):979–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieira RL, Rosenberg ZS, Kiprovski K. MRI of the distal biceps femoris muscle: normal anatomy, variants, and association with common peroneal entrapment neuropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(3):549–555. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurist KA, Greene PW, 3rd, Shirkhoda A. Peroneal nerve dysfunction as a complication of lateral meniscus repair: a case report and anatomic dissection. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(2):141–147. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(89)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch A, Wyzykowski RJ, Victoroff BN. Evaluation of the anatomy of the common peroneal nerve. Defining nerve-at-risk in arthroscopically assisted lateral meniscus repair. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):10–15. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan W, Mahony N, Delaney M, O’Brien M, Murray P. Relationship of the common peroneal nerve and its branches to the head and neck of the fibula. Clin Anat. 2003;16(6):501–505. doi: 10.1002/ca.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochman MG, Zilberfarb JL. Nerves in a pinch: imaging of nerve compression syndromes. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(1):221–245. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tehranzadeh J. The spectrum of avulsion and avulsion-like injuries of the musculoskeletal system. Radiographics. 1987;7(5):945–74. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.7.5.3331209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keats TE. The lower extremity – The proximal ends of the tibia and fibula. In: Keats TE, editor. Atlas of normal roentgen variants that may simulate disease. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1992. pp. 582–583. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinner RJ, Desy NM, Rock MG, Amrami KK. Peroneal intraneural ganglia. Part I. Techniques for successful diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(6):E16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galloway HR. Muscle denervation and nerve entrapment syndromes. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14(2):227–235. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS. Entrapment neuropathies of the upper extremity. In: Stoller DW, editor. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine. Wilkins: Lippincott; 2006. pp. 1935–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendszus M, Koltzenburg M, Wessig C, Solymosi L. Sequential MR imaging of denervated muscle: Experimental study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(8):1427–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleckenstein JL, Watumull D, Conner KE, Ezaki M, Greenlee RG, Jr, Bryan WW, Chason DP, Parkey RW, Peshock RM, Purdy PD. Denervated human skeletal muscle: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 1993;187(1):213–218. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valle M, Zamorani MP. Nerve and blood vessels. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 97–136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niall DM, Nutton RW, Keating JF. Palsy of the common peroneal nerve after traumatic dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(5):664–667. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruber H, Peer S, Meirer R, Bodner G. Peroneal nerve palsy associated with knee luxation: evaluation by sonography–initial experiences. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(5):1119–2. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones BG, Mehin R, Young D. Anatomical study of the placement of proximal oblique locking screws in intramedullary tibial nailing. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89(11):1495–1497. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.19018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrot P, Stines J, Walter F, Martinet N, Paysant J, Blum A. Imaging of the painful lower limb stump. Radiographics. 2000;20:S219–235. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.suppl_1.g00oc14s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chhabra A, Williams EH, Wang KC, Dellon AL, Carrino JA. MR neurography of neuromas related to nerve injury and entrapment with surgical correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(8):1363–1368. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeom DH, Lee J, Cho WH, Kim JH, Jeong MJ, Kim SH, Kim JY, Kim SH, Kang MJ, Lee HB, Bae KE. Idiopathic acute isolated lateral compartment syndrome of a lower leg: a magnetic resonance imaging case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68(1):57–61. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2013.68.1.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebenezer S, Dust W. Missed acute isolated peroneal compartment syndrome. CJEM. 2002;4(5):355–358. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500007776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peeters J, Vanhoenacker FM, Camerlinck M, Parizel PM. Calcific myonecrosis. JBR–BTR. 2010;93(2):111. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert BC, Bui-Mansfield LT, Dejong S. MRI of a Morel-Lavallée lesion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(5):1347–1348. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellado JM, Pérez del Palomar L, Díaz L, Ramos A, Saurí A. Long-standing Morel-Lavallée lesions of the trochanteric region and proximal thigh: MRI features in five patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(5):1289–94. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iverson DJ. MRI detection of cysts of the knee causing common peroneal neuropathy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1829–31. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187098.42938.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spinner RJ, Amrami KK, Rock MG. The use of MR arthrography to document an occult joint communication in a recurrent peroneal intraneural ganglion. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35(3):172–179. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedrazzini M, Pogliacomi F, Cusmano F, Armaroli S, Rinaldi E, Pavone P. Bilateral ganglion cyst of the common peroneal nerve. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(11):2803–2806. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luigetti M, Sabatelli M, Montano N, Cianfoni A, Fernandez E, Lo Monaco M. Teaching neuroimages: peroneal intraneural ganglion cyst: a rare cause of drop foot in a child. Neurology. 2012;78(7):e46–47. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318246d6e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinner RJ, Desy NM, Amrami KK. Sequential tibial and peroneal intraneural ganglia arising from the superior tibiofibular joint. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(1):79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinner RJ, Atkinson JL, Scheithauer BW, Rock MG, Birch R, Kim TA, Kliot M, Kline DG, Tiel RL. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. Clinical series. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(2):319–329. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.2.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinner RJ, Luthra G, Desy NM, Anderson ML, Amrami KK. The clock face guide to peroneal intraneural ganglia: critical “times” and sites for accurate diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(12):1091–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphey MD, Smith WS, Smith SE, Kransdorf MJ, Temple HT. From the archives of the AFIP. Imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19(5):1253–1280. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se101253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isobe K, Shimizu T, Akahane T, Kato H. Imaging of ancient schwannoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(2):331–336. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonar SF, Viglione W, Schatz J, Scolyer RA, McCarthy SW. An unusual variant of intraneural ganglion of the common peroneal nerve. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35(3):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li CS, Huang GS, Wu HD, Chen WT, Shih LS, Lii JM, Duh SJ, Chen RC, Tu HY, Chan WP. Differentiation of soft tissue benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors with magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging. 2008;32(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jee WH, Oh SN, McCauley T, Ryu KN, Suh JS, Lee JH, Park JM, Chun KA, Sung MS, Kim K, Lee YS, Kang YK, Ok IY, Kim JM. Extraaxial neurofibromas versus neurilemmomas: discrimination with MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(3):629–633. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parizel PM, Geniets C. Tumors of the peripheral nerve system. In: De Schepper A, Vanhoenacker F, Gielen J, Parizel PM, editors. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 325–354. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Shido Y, Sugiura H, Nakashima H, Ishiguro N. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568–1574. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin J, Martel W. Cross-sectional imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: characteristic signs on CT, MR imaging, and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):75–82. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanhoenacker FM, Marques MC, Garcia H. Lipomatous Tumors. In: De Schepper A, Vanhoenacker F, Gielen J, Parizel PM, editors. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 227–261. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20(5):1407–1434. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se171407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valle M, Zamorani MP. Bone and joint. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 137–185. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanhoenacker FM, Van Hul W, Wuyts W, Willems PJ, De Schepper AM. Hereditary multiple exostoses: from genetics to clinical syndrome and complications. Eur J Radiol. 2001;40(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(01)00401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson LW, Torch MA. Peroneal nerve palsy secondary to compression from an osteochondroma. Orthopedics. 1993;16(6):707–710. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930601-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malghem J, BC Vb, Lebon C, Lecouvet FE, Maldague BE. Ganglion cysts of the knee: articular communication revealed by delayed radiography and CT after arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1579–1583. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.6.9609177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinoli C, Bianchi S. Knee. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 636–744. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward WG, Eckardt JJ. Ganglion cyst of the proximal tibiofibular joint causing anterior compartment syndrome. A case report and anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(10):1561–1564. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199410000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ashton LA, Jarman PG, Marel E. Peroneal compartment syndrome of non-traumatic origin: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2001;9(2):67–69. doi: 10.1177/230949900100900214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]