Abstract

Background

This study examined venue-based networks constituted by affiliation with gay bars and street intersections where male sex workers (MSWs) congregate to find their sexual/drug-sharing partners, and network influence on risky sexual behavior (e.g., unprotected anal intercourse [UAI]) and HIV infection.

Methods

Data collected during 2003–2004 in Houston, Texas, consists of 208 MSWs affiliated with 15 gay bars and 51 street intersections. Two-mode network analysis was conducted to examine structural characteristics in affiliation networks, as well as venue-based network influence on UAI and HIV infection.

Results

Centralized affiliation patterns were found where only a few venues were popular among MSWs and these were highly inter-dependent. Distinctive structural patterns of venue-based clustering were associated with UAI and infection. Individuals who shared venue affiliation with MSWs who engage in UAI were less likely to have UAI themselves. This suggests a downhill effect, i.e., individuals compensate for their risk of infection by adjusting their own risk-taking behavior, based on their perceptions of their venue affiliates.

Conclusions

Venue-based HIV/AIDs interventions could be tailored to specific venues so as to target specific clusters that are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior.

Keywords: social network analysis, risky sexual behavior, HIV diffusion, affiliation networks, male sex workers

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) accounted for 61% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in 2009, despite representing only 2% of the US population (1). MSM are embedded in social contexts influencing the likelihood of engaging in risk and protective behaviors. A number of social network studies have identified network characteristics that contribute to an individual’s level of risk behaviors, perception of infection risk, or infectious outcomes. These network characteristics include occupying central, peripheral, or bridging positions within network chains, being a member of a network core group, personal network density, having multiple social connections, network distance between infected and susceptible persons, and disassortative mixing (2–10).

Although the utility of social network analysis for understanding how infectious diseases spread through behavioral risk networks (11), social network analysis has rarely been used to investigate the relationship between social venues and disease transmission (12–14) or the behaviors that contribute to or prevent infection (15). Disease incidence and related risk behaviors have been shown to be highly associated with social venues where people meet friends, find sex partners, or interact with drug use partners (16–18). Because social venues are often used to meet sex partners, a venue and its associated sexual networks is called a “sexual affiliation network” (12).

Risky social venues provide settings for MSM to interact with their peers, where they form networks based upon affiliations with specific venues. As HIV prevalence is known to be especially high among male sex workers (MSWs), this study examined venue-based affiliation networks of MSWs and the relation of network structures to risky sexual behavior (defined as unprotected anal intercourse (UAI)) and HIV status. We defined MSWs as those who exchange sex for money. There were two aims in this study. Firstly, the structural features of MSW’s affiliated networks were identified by the popular venues with which they were connected and by clustering patterns associated with UAI and HIV infection. Secondly, the potential venue-based network influence on UAI was assessed. The study’s original hypothesis was that the more an individual was exposed to MSWs who engage in UAI through shared venue affiliation, the more likely that individual was to have UAI.

Materials and Methods

Procedures

Data for the study were collected between May 2003 and February 2004 for a project investigating the social, drug-use, and sexual networks of drug-using MSWs. MSWs were recruited for the study using a combination of targeted sampling and participant referral (19, 20) that have been described elsewhere (21). Briefly, a purposeful sampling plan was developed wherein key informants knowledgeable about male sex work in the city were interviewed to identify neighborhoods and venues with high rates of drug use and/or solicitation of sex-for-money. Once neighborhoods were identified, informants and study personnel were then asked to recruit men apparently engaged in sex work.

After being interviewed for the study, respondents were asked to name their social, sexual, and drug-use contacts in the last 48 hours. A list of named contacts was created and weighted by drug-use and sexual risk behaviors. By weighting we mean network contacts using drugs or having sex with the respondent were selected before other network contacts such that those weighted higher had a greater likelihood of selection. The respondent was given the names of the selected individuals and was then asked to recruit them as secondary contacts. This process was repeated with secondary contacts to sample tertiary contacts. Study procedures and data collection instruments were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Measures

Data were collected by trained research assistants using the Sexual Network Questionnaire. Two dependent variables were created to measure UAI and HIV status. UAI was defined as “never using condoms” based on a measure of frequency of condom use during anal sex in the last 7 days. HIV status was based on respondents’ self-reports of either never having been tested for HIV or having been tested as HIV positive or negative. Socioeconomic and demographic measures of age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, homeless status, lifetime frequency of arrest, and the total number of sex partners in the last 30 days, were used in this study as controlled variables. A sexual partner was measured as a paying or a nonpaying partner with whom a respondent had oral, anal, or vaginal sex. The size of a sexual network was the sum of a respondents sex partners. Because of recall issues, we set the upper limit of reported sex partners at 150.

Risky venues were defined as bars and streets intersections where MSWs reported meeting sex/drug-injecting partners. To measure risky venues, respondents were asked to name the places where they regularly spent time looking for sex partners. Most named places were bars or street intersections. The validity and consistency of bar names were assessed by key informants. If respondents named a street, they were asked to name the two streets composing the nearest intersection. The intersections were validated using city maps and then geo-coded.

Analysis

A sample 334 males (84.3%), and 62 females (totaling 396 respondents) were interviewed. The sample was filtered down to 257 (76.9%) males who reported a history of trading sex for money, as our study focused on networks among MSWs. Among these 257 respondents, 122 (47.5%) hung out at named bars and 209 (81.3%) at named intersections. As the aim of this study was to examine affiliation patterns of risky social places among MSWs, the sample was restricted to those who hung out at at least one of 15 identifiable bars or 51 identifiable intersections. Limiting the sample to MSW who hung out at an identifiable bar or intersection resulted in an analytical sample of 208 MSWs (more information found in the online supplement). The filtered cases (N=188) did not differ significantly from the analytic sample (N=208) by HIV status, UAI, age, or race. However, the filtered cases had fewer sex partners in the last 30 days (AOR=0.98; p<0.01), were less likely to have been arrested (AOR=0.97; p<0.01), and were more likely to self-identify as heterosexual (AOR=6.08; p<0.001) or bisexual (AOR=1.86; p<0.05). Differences indicated that respondents who were excluded from the analytical sample exhibited fewer risk factors, so results should be interpreted with this caveat.

Data were first analyzed using two-mode network analysis by creating affiliation networks composed of two modes. The first mode was a set of MSWs (N=208). The second mode was the set of venues of gay bars and intersections (V=66) with which MSWs were affiliated. Multiple analyses were then used to examine the affiliation networks among MSWs and risky social venues.

First, we constructed a visual representation of the affiliation networks between MSWs and risky social venues. We identified centrally positioned venues and MSWs using centrality measures that allow us to determine the relative prominence of venues/MSWs within the network. To quantify the level of centrality for both MSWs and venues, we used degree-based centrality measures by counting the number of venues in which a MSW hung out (MSW degree centrality) and the number of MSWs who hung out in the venue (venue degree centrality). We also weighted these degree concentrations proportional to the sum of the concentrations of the venues to which an MSW was adjacent (MSW eigenvector centrality) and to the sum of concentrations of MSWs to which the edge was adjacent (venue eigenvector centrality). We then normalized both degree concentrations (22, 23). (See the online supplement for more detailed computations and justification of using these measures).

Second, we constructed two alternate graph projections: a co-affiliation network among MSWs whereby each pair of MSWs is connected through sharing at least one common venue, and a co-occurrence network among risky social venues whereby each pair of venues is connected through sharing at least one common MSW. We further identified clusters of MSWs in a co-affiliation network among MSWs using a spring-embedding algorithm, whereby a pair of MSWs who shared the same venues formed each cluster (see online supplement for technical description). The goal was to visually represent the structural patterns of affiliation networks in terms of characteristics of the MSWs (i.e., UAI or HIV status) or type of risky social venues (i.e., bars or intersections). Graphs were constructed using NetDraw 2.809 (24).

Third, we measured the levels of exposures to a specific behavior within networks formed by MSWs affiliating with the same venues by employing an “affiliation exposure model” (25, 26). In this application, affiliation exposure measured the extent to which individual MSWs were exposed to other MSMs who engage in UAI or HIV status through shared affiliation with bars or street intersections. Computations of affiliation exposure involve two components: (a) the number of venues with which each pair of MSWs shared affiliation, and (b) the number of venues with which each MSW affiliated. Affiliation exposures were then computed using (a), the proportion of venues affiliated with other MSWs who had UAI, weighted by the proportion of venues that each pair of MSWs shared. For example, if John hung out at the same bar as Sam, who engages in UAI, and Jack, who does not have UAI, John’s exposure to peer UAI through the bar affiliation is 50%. The component of (b), being equivalent to individual degree centrality, was not included in the computation, but was included as one of the control variables in the regression analysis. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to test for an association between affiliation exposure and UAI and HIV status. Multiple imputations via switching regression, an iterative multivariable regression technique by chained equations (27), was conducted to deal with missing values.

Results

As shown in Table 1, more than half of the analytic sample was white, bisexual or heterosexual, and homeless. The average age was 31.6 years. The sample had an average of 44 sex partners in the last 30 days, and had been arrested in their lifetime an average of 14 times. Approximately 24% of the sample was HIV positive and 30% had UAI in the last 7 days.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Percentages or Means with Standard Deviations, Min, and Max Values for Characteristics of MSW (N=208)

| Percentages or Mean (SD; Min, Max) | |

|---|---|

| HIV status | |

| Positive | 24.04 % |

| Negative | 62.02 % |

| Unknown | 13.94 % |

| UAI | |

| Yes (non-condom use) | 29.81 % |

| No (condom use) | 47.12 % |

| Unknown | 23.08 % |

| Age | 31.63 (7.36; 18, 53) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 50.96 % |

| African American | 38.94 % |

| Hispanic/Latino or other | 10.10 % |

| Homeless | 56.25 % |

| Sexuality | |

| Homosexual | 39.90 % |

| Straight or Bisexual | 60.10 % |

| Number of sex partners in the last 30 days | 44.18 (42.97; 0, 150) |

| Number of times arrested in lifetime | 13.61 (15.12; 0, 90) |

| Affiliation exposure | |

| UAI | 0.27 (0.20; 0, 1) |

| HIV positive | 0.22 (0.18; 0, 1) |

Visualization of affiliation network

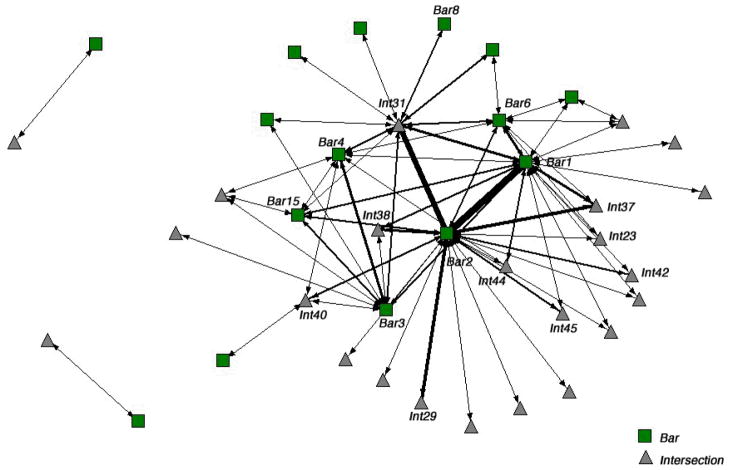

Figure 1 represents the affiliation network formed by 208 MSWs and 66 venues consisting of 15 gay bars and 51 street intersections.

Figure 1.

Affiliation network between 208 MSWs and 66 venues of bar and intersection

Note: Blue circles represent MSWs, green squares represent bars, and grey triangles represent intersections. There are wide variations in the popularity of risky social places; a few bars and intersections are clearly dominant and attract many MSWs, and these popular venues (Int #31, Bar #2, and Bar #1) are located in the central position of the affiliation network.

There are three main observations to be taken from the Figure 1.

There are wide variations in the popularity of risky social places, with only a few bars and intersections attracting many MSWs

These popular venues are located in a central position in the affiliation network. The table in the online supplement reports scores for each centrality measures among top 25 venues or individual MSWs as well as basic statistics. Intersection (Int) #31 had the highest concentration scores (i.e., venue degree centrality), followed by Bar #2, and Bar #1. The concentration scores among MSWs (MSW degree centrality) have little variation, as most respondents nominated only one bar or intersection venue. Some MSWs (such as #1, #2, #7, #8, and #9) had a relatively higher concentrations scores (i.e., MSW eigenvector centrality) as a consequence of affiliating with popular venues.

Popular intersections and bars (Int #31, Bar #2, and Bar #1) tended to be connected to the same MSWs

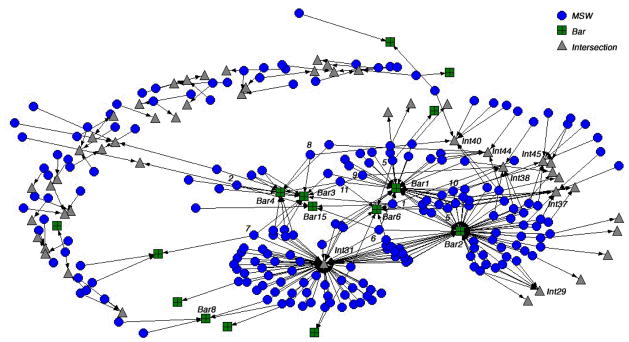

Figure 2 represents a co-occurrence network among intersections and bars where each pair of venues are connected if they had at least one common MSW (removing any truly solitary ones).

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence network of MSWs among venues without isolated venues

Note: Each pair of venues is connected if they shared at least one common MSW. Green squares represent bars and grey triangles represent intersections. The width of the link represents the number of shared MSWs for each pair of venues (i.e., a thicker line represents more shared MSWs). By observation, it is clear that Bar #2 shares more MSWs with Bar #1, and with Int #31. Bar #2 also shares MSWs with Int #29 and Int #37 to a lesser extent. MSWs who hang out at Int #31 also affiliated with centrally located bars (i.e., Bar #2, Bar #1) but also with other bars that were marginally located.

The data show Bar #2 had more patrons with Bar #1. MSWs connected to Bar #2 were also connected to Int #31, Int #29, and, to a lesser extent, Int #37. MSWs connected to Int #31 were also connected to two centrally located bars (Bar #2, Bar #1), as well as other more marginally located bars. Centrally located venues (Int #31, Bar #2, and Bar #1) were within short geographic distance of each other (about 100 yards). The co-occurrence network shows that bars are connected with other bars or intersections, but hardly any intersections are connected to other intersections, indicating an interdependency between bars and intersections as risky social venues, but not intersections alone.

Subgroups of MSWs formed through affiliating with specific bars or intersections

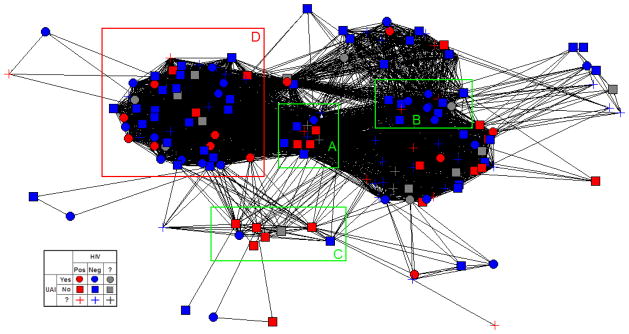

Figure 3 illustrates a co-affiliation network among MSWs, where each pair of MSWs is connected if they report at least one venue in common.

Figure 3.

Co-affiliation network consisting of 164 MSWs forming the component

Note: Each pair of MSWs is connected if they share at least one common venue. Red represents HIV positive persons, blue represents HIV negative, and grey represents unknown HIV status, with circles representing those who engage in UAI, squares representing those who do not engage in UAI, and plus-signs representing unknown UAI status. Green and red boxes (A–D) represent a clustering of MSWs through affiliation with specific venues. Box A illustrates a cluster of 12 MSWs who affiliated with the centrally located venues of Int #31 and Bar #2, and their HIV status was almost evenly distributed while only one of them (blue circle) had UAI. Box B illustrates a cluster of 14 MSWs who affiliated with at least two venues of Bar #1 and Bar #2, and their HIV status was mostly negative while their UAI status was almost evenly distributed. Box C illustrates a cluster of 8 MSWs who affiliated with at least one of Bar #3, #4, and #15, most of whom were HIV positive and all of whom did not have UAI. Box D illustrates a cluster that contains 7 MSWs who self-reported as HIV positive and as having UAI (red circles).

Figure 3 shows the largest component of the network (i.e., two MSWs are defined as members of the component if there is a path connecting them), consisting of 164 MSWs. Additionally, Figure 3 includes three clusters, A, B, C, indicated by green boxes, and one cluster, D, indicated by the red box. Clustering of MSWs is by specific venue, which displays some differences or similarities between clusters by HIV status and UAI (see online supplement for technical information of obtaining these clusters). Cluster A is a cluster of 12 MSWs who are affiliated with centrally located venues Int #31 and Bar #2. The HIV status of the members of this cluster was evenly distributed across response categories, where 4 were “HIV positive,” 6 were “HIV negative,” and 2 were “unknown.” Only one of member of this cluster (blue circle) was engaging in UAI. Six members were “non-UAI” and 5 responded “unknown.”

Cluster B consists of 14 MSWs affiliated with at least two venues, Bar #1 and Bar #2. Their HIV status was mostly negative (11 negative, 2 positive, and 1 unknown), while UAI was almost evenly distributed across response categories (6 “UAI,” 6 “non-UAI,” and 2 responded “unknown”). Cluster C is a cluster of 8 MSWs affiliated with one of three bars, #3, #4, and #15. Five out of the 8 MSWs in this cluster were HIV positive. All members of the cluster were non-UAI. Cluster D consists of 7 MSWs who self-reported being HIV positive and UAI (red circle). This cluster contains a mix of MSWs in terms of their UAI and HIV status.

Affiliation exposure model

We computed two separate affiliation exposures measuring the extent to which MSWs are exposed to venue co-affiliates of UAI, and exposed to co-affiliates who reported being HIV positive, as shown in Table 1. Any missing values of UAI and HIV status were not included in these computations. Table 2 shows the results of logit models.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Outcome Variables of UAI and HIV Status based on Logit Models (N=208 MSWs)

| UAI | HIV positive | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 (0.03)* | 1.08 (0.04)* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 2.06 (0.84) | 1.43 (0.64) |

| Hispanic/Latino or other | 4.79 (3.32)* | 1.09 (0.77) |

| Homeless | 1.61 (0.60) | 1.01 (0.45) |

| Homosexual | 1.04 (0.37) | 13.68 (6.13)** |

| Number of sex partners in the last 30 days | 0.99 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| Number of times arrested in life time | 1.00 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.02) |

| Number of venues affiliated | 1.32 (0.34) | 1.28 (0.39) |

| Affiliation exposure | ||

| UAI | 0.20 (0.16)† | 0.84 (0.82) |

| HIV positive | 1.24 (1.04) | 2.37 (2.34) |

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Note: Tests are based on a two-tailed test; parentheses represent standard errors. For race/ethnicity, White was used as a reference category. 23.56% had missing values at least one of the UAI and other controlled variables, and 14.42 % were missing at least values for one of the HIV status or other controlled variables. Multiple imputations have been conducted.

The effect of affiliation exposure to co-affiliates who engaged in UAI was almost statistically significant (AOR=0.20; p=0.052) using a two-tailed test. The estimated odds ratio showed a negative association, indicating that as MSWs were increasingly exposed to other MSWs who engaged in UAI (via risky social venues), they were less likely to have UAI. This association was significant at a one-tailed test at alpha=0.05 level. The effect of affiliation exposure to HIV-positive MSWs through venue was not a significant predictor of both of our outcome variables. The regression models also showed older MSWs (AOR=1.07; p<0.05) or Hispanic/other MSWs (AOR=4.79; p<0.05) were more likely to have UAI. Additionally, older MSWs (1.08; p<0.05) and MSWs who identified as homosexual (AOR=13.68; p<0.01) were more likely to be HIV positive.

Discussion

Our study examined the structural features of venue-based MSWs’ affiliation with gay bars and street intersections in relation to risky sexual behavior and HIV infection. Using two-mode network analysis, our results show venue-based affiliation networks are characterized by a centralized structure of only a few bars and intersections. These popular bars and intersections are interdependent, having many of the same MSWs in common. Additionally, we found distinctive patterns of clustering among MSWs characterized by risky sexual behavior and HIV status associated with specific risky social venues affiliations.

In terms of network influence through affiliation, results indicate that, as MSWs were increasingly exposed to risky venue environment, including others who engage in risky sexual behavior, they tend to engage in more protective behavior. This result was contrary to our hypothesis of how network influence affected frequency of risk-taking behavior amongst venue co-affiliates, as it is counterintuitive considering the expected homophily effect among MSWs through venue affiliation. This counter-intuitive result could be the effect of “risk compensation,” whereby individuals compensate for perceived risk inherent in their environment by adjusting their behaviors. More specifically, our result suggests MSWs adjust their behavior in response to their perceptions of increased risk of disease infection by engaging in sexual behavior with others whom they met at certain gay bars or intersections. Our result may also indicate the “downhill phenomenon” (28) whereby people normally compare their own risk with someone who is at much greater risk than themselves (29), so they can think of themselves as being safer, except for those who are furthest “downhill,” who have almost no-one they can identify at higher risk: they must thus make a realistic assessment of their own risk and thus are less likely to engage in unrealistic risk-taking behaviors.

Findings from this study could provide new directions in developing network interventions in public health (30), focusing on venue-targeted HIV/AIDS prevention intervention programs. For instance, a program could increase its impact by targeting the structurally identified risky venues where risk-taking MSWs hang out. Additionally, by identifying the overlapping venues frequented by MSWs, programs can avoid wasting resources on the same subpopulation and instead focus on others.

Our findings are tempered by some limitations: first, our study included specified gay bars and street intersections as main risky social venues where male sex workers congregate to find their sex or drug-injecting partners. Network influence through risky social venue affiliation may not be limited to these venues. Second, as our results used cross-sectional data. Cross-sectional limited investigating the process of selective affiliation with risky social venues based on behavioral homophily. For example, cross-sectional data cannot necessarily show why MSWs with similar behaviors congregate at specific risky venues. Third, related to the second limitation, our analysis is based on cross-sectional affiliation data. Consequentially, there is a limitation in understanding potential causality of venue affiliation leading to HIV risk, as well as potentially dynamic patterns of venue affiliation in a network. Fourth, the study examined data collected in one major metropolitan area, limiting the generalizability of the results to other geographic locations. Venue availability and popular venues among MSM differ by regional characteristics, such as the relative mixing between distinct racial/ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Lastly, our findings are based only on physical venues of gay bars and street intersections where MSWs were highly likely to meet sex partners. Our data did not include virtual venue affiliation, such as Facebook, mySpace, etc. However, our data were collected in 2003–2004, when online meeting or social networking sites were not as popular among MSM as today. Nevertheless, future research should investigate virtual venue affiliations.

Despite these limitations, our study offers an empirical investigation into venue-based networks created by MSWs’ affiliation with risky social venues. This research shifts attention from solely direct person-to-person contact networks. For certain sub-populations among MSM strongly associated with specific venues, especially male sex workers, investigation of venue-based network structure may provide better insights into the social mechanisms of disease transmission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This study was supported by the NIH/NIDA10205 (PI: Williams, M.L.) and NIH/NIAAA 4R00AA019699 (PI: Fujimoto, K.). We acknowledge John Atkins for managing data, and Erik H. Lindsley for technical supports.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest exists in this manuscript.

References

- 1.CDC. HIghlights of CDC activities addressing HIV prevention among African American gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach DM, Darrow WW, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: patients linked by sexual contact. American Journal of Medicine. 1984;76:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettinger JA, Adler NE, Curriero FC, Ellen JM. Risk perceptions, condom use, and sexually transmitted diseases among adolescent females according to social network position. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31(9):575–579. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000137906.01779.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fichtenberg CM, Muth SQ, Brown B, Padian NS, Glass TA, Ellen JM. Sexual network position and risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:493–498. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Curtis R, Goldstein M, Ildefonso G, et al. Sociometric risk networks and risk for HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(8):1289–1296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klovdahl AS, Potterat JJ, Woodhouse DE, Muth JB, Muth SQ, Darrow WW. Social networks and infectious disease: The Colorado Springs study. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latkin CA, Mandell W, Vlahov D, Knowlton A, Oziemkowska M, Celentano D. Personal network characteristics as antecedents to needle-sharing and shooting gallery attendance. Social Networks. 1995;17(304):219–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Schumm P, Laumann EO, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valente TW, Fujimoto K. Bridges: locating critical connectors in a network. Social Networks. 2010;32(3):212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman SR, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2001;78(3):411–418. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost SDW. Using sexual affiliation networks to describe the sexual structure of a population. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(Suppl I):i37–i42. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway IW. Using venue-based social network analysis to guide HIV and substance abuse prevention. Sunbelt XXXII, International Sunbelt Social Network Conference; Redondo Beach, CA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klovdahl AS, Graviss EA, Yaganehdoost A, Ross MW, Wanger A, Adamse GJ, et al. Networks and tuberculosis: an undetected community outbreak involving public places. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:681–694. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider JA, Walsh T, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Laumann EO. HIV health center affiliation networks of black men who have sex with men: disentangling fragmented patterns of HIV prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39(8):598–604. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182515cee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binson D, Woods WJ, Pollack L, Paul J, Stall R, Catania JA. Differential HIV risk in bathhouses and public cruising areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1482–1486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klovdahl AS. Social networks and the spread of infectious diseases: The AIDS example. Social Science & Medicine. 1985;21(11):1203–1216. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potterat JJ, Rothenberg RB, Woodhouse DE, Muth JB, Pratts CI, Fogle JS., 2nd Gonorrhea as a social disease. Sexually Transmitted Disease. 1985;12(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heckathorn D, Semaan S, Broadhead R, Hughes J. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of injection drug users aged 18–25. AIDS Behavior. 2002;6:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams ML, Ross M, Bowen A, et al. An investigation of condom use by frequency of sex. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:433–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.6.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams ML, Atkinson J, Klovdahl AS, Ross MW, Timson S. Spatial bridging in a network of drug-using male sex workers. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005;82(Suppl 1):i35–i42. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonacich P. Simultaneous group and individual centralities. Social Networks. 1991;13:155–168. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borgatti SP, Everett MG. Network analysis of 2-mode data. Social Networks. 1997;19:243–269. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borgatti SP. NetDraw: Graph Visualization Software. MA: Harvard: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto K, Chou C-P, Valente TW. The network autocorrelation model using two-mode network data: Affiliation exposure and biasness in ρ. Social Networks. 2011;33(3):231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujimoto K, Unger JB, Valente TW. Network method of measuring affiliation-based peer influence: assessing the influences on teammates smokers on adolescent smoking. Child Development. 2012;83(2):442–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstein N. Perceptions of personal susceptibility to harm. In: Mays VM, Albee GW, Schneider SF, editors. Primary prevention of AIDS: psychological approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan B, Ross MW. Preventing HIV: determinants of sexual behavior. Lancet. 2000;355:1897–1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valente TW. Network Interventions: A Taxonomy of Behavior Change Interventions. Science. in press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.