Abstract

Objective

Metabolic abnormalities including diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and abdominal obesity occur commonly in HIV patients, are associated with increased coronary artery calcification (CAC), and contribute to increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) in this population. We hypothesized that lifestyle modification (LSM) and metformin would improve CVD indices in HIV patients with metabolic syndrome.

Design

A randomized, placebo controlled trial to investigate LSM and metformin, alone and in combination, over one year, among 50 HIV-infected patients with metabolic syndrome.

Methods

We assessed CAC, cardiovascular and metabolic indices.

Results

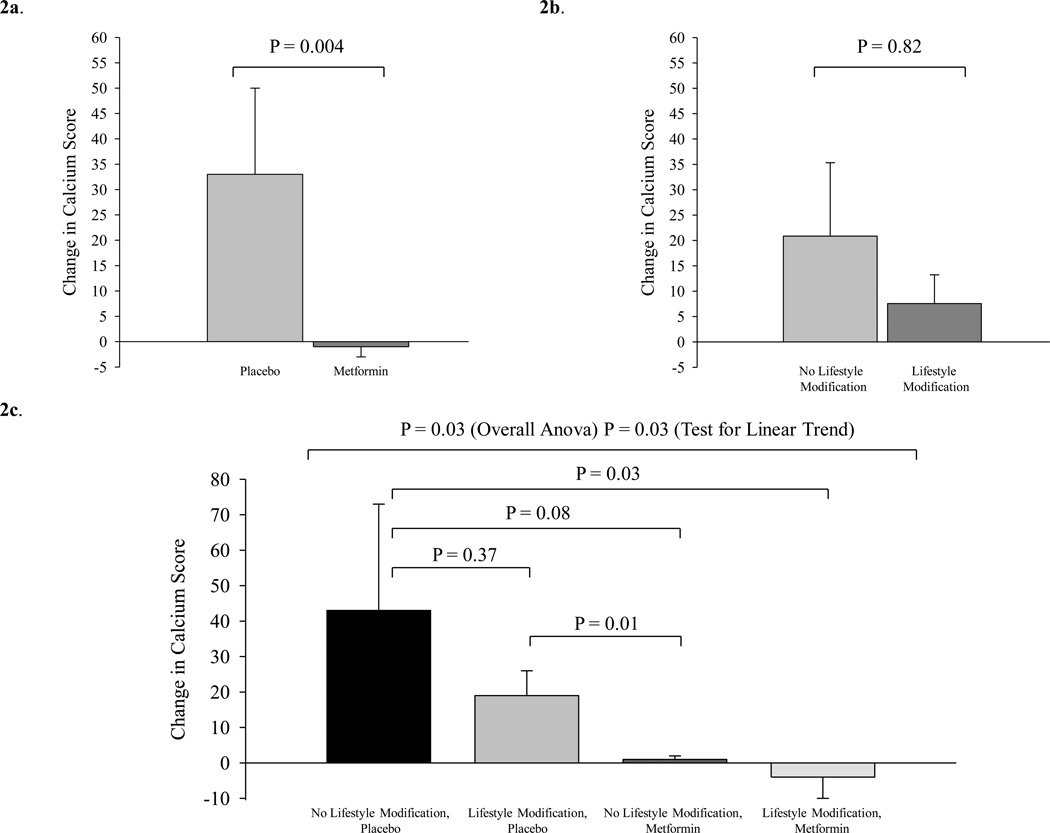

Among the participants, duration of HIV-infection was 14±1 yr and duration of antiretroviral therapy was 6±1 yr. Metformin-treated subjects demonstrated significantly less progression of CAC (−1±2 vs. 33±17, P=0.004, metformin vs. placebo) whereas the effect of LSM on CAC progression was not significant (8±6 vs. 21±14, P=0.82, LSM vs. no LSM). Metformin had a significantly greater effect on CAC than LSM (P=0.01). Metformin-treated subjects also demonstrated less progression in calcified plaque volume (−0.4±1.9 vs. 27.6±13.8 mm3, P=0.008) and improved HOMA-IR (P=0.05) compared to placebo. Subjects randomized to LSM vs. no LSM showed significant improvement in HDL (P=0.03), hsCRP (P=0.05), and cardiorespiratory fitness. Changes in CAC among the 4 groups: 1) no LSM, placebo (43±30); 2) LSM, placebo (19±7); 3) no LSM, metformin (1±1); and 4) LSM, metformin (−4±6) were different (P=0.03 for ANOVA and linear trend across groups), the majority of this effect was mediated by metformin. Results are mean ± SEM.

Conclusion

Metformin prevents plaque progression in HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Lifestyle modification, metformin, HIV, atherosclerosis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increasingly common among HIV-infected patients, with recent studies demonstrating increased rates compared to non-HIV-infected patients [1–3]. In addition, significant subclinical coronary artery disease is seen even among HIV patients without known heart disease [4]. Metabolic abnormalities, including diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, hypertension, and abdominal obesity are common in HIV-infected patients and may contribute to the increased risk of CVD in this population. Metabolic syndrome (MS) is increased among HIV-infected patients [5–8] and associated with increased coronary artery calcification (CAC) [9].

Clinical guidelines for HIV and non-HIV-infected patients with MS stress the importance of lifestyle modification (LSM) [10–12]. In addition, interest has focused on modulating insulin resistance. Metformin was shown to significantly reduce CVD events in the UKPDS study of 1704 non-HIV, overweight, type II diabetics receiving dietary management alone, randomized to metformin, sulfonylurea or conventional therapy [13]. However, longer term studies with these strategies have not been performed among HIV-infected patients, investigating effects on atherosclerotic indices.

In the present study, we investigated LSM and metformin, alone and in combination, among HIV-infected patients with MS over a relatively long-treatment period of one year. We hypothesized that treatment with LSM and metformin would improve measures of subclinical atherosclerosis in this population.

Methods

Subjects

The study was conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) between December 2006 and July 2010. Eligibility requirements included: previously documented HIV infection, age between 18 and 65 years, on a stable HIV treatment regimen for more than 6 months and demonstration of NCEP defined MS [11].

Subjects were excluded if they had had any new serious opportunistic infection within the past 6 weeks, history of unstable angina, aortic stenosis, uncontrolled hypertension, contraindication to physical activity, current therapy with insulin, other diabetic agents, or fasting blood sugar >6.99mmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level >2.5× upper limit of normal (ULN), creatinine >132.6µmol/L, lactic acid > than 2× ULN, history of allergy to metformin or IV contrast dye, glucocorticoid therapy, estrogen, or progestational derivative within 3 months of the study, current substance abuse, hemoglobin <6.21mmol/L, pregnant, or using supraphysiological doses of testosterone or physiological testosterone replacement for less than 3 months.

Subjects were recruited through advertising in the Boston area. Informed written consent was obtained before study participation and the protocol was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee.

Intervention

The effects of metformin and/or LSM were studied over one year in a randomized, placebo-controlled 2×2, 4 group factorial study. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of four groups: 1) no lifestyle modification (no LSM), placebo; 2) LSM, placebo; 3) no LSM, metformin; or 4) LSM, metformin. Randomization was stratified by gender, age, and protease inhibitor use. The treatment groups received metformin or identical placebo 500mg twice a day, with a dose increase to 850mg twice a day after 3 months, if lactic acid and creatinine levels were within normal limits and no side effects were reported. Investigators and study staff were blinded to treatment assignment. Randomization was performed by the Harvard Catalyst Biostatistics Program at MGH. A computer generated stratified permuted blocks randomization table was created and kept by the MGH Pharmacy. Those randomized to LSM in the study participated in 3 supervised exercise sessions/week during the 12 months of the study with dietary counseling occurring once a week (see Supplemental Methods).

Cardiovascular Parameters

CT imaging was performed using a SOMATOM Sensation (Siemens Medical Solutions) 64-slice CT-scanner as previously described [9] (see Supplemental Methods). cIMT imaging of the common carotid artery was conducted using a high-resolution 7.5-MHz phased-array transducer (SONOS 2000/2500) as previously described [14] (see Supplemental Methods).

Exercise and Dietary Assessment

A submaximal exercise stress test was conducted on a cycle ergometer to measure endurance. Dietary intake information was assessed by a 4-day self-documented food record using Minnesota Nutrition Data System software. One repetition maximum (RM) was determined for 6 major muscle groups (see Supplemental Methods).

Metabolic, Biochemical and Immunological Parameters

Fasting HDL, triglycerides, glucose, lactate levels, creatinine, ALT, were determined using standard techniques. Insulin was measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay (Beckman) and HOMA-IR was determined. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (R&D), PAI-1 (Siemens) and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) (Roche Diagnostics) were determined. CD4+ T-cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry. HIV viral load was determined by the COBAS Ampliprep (Roche Diagnostics).

Body Composition Assessment

Abdominal visceral adipose area (VAT) and subcutaneous area (SAT) were assessed by MRI at the level of the L4 pedicle [15, 16]. Intramyocellular lipid (IMCL) of the tibialis anterior was determined using 1H-MRS [17]. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was used to assess extremity fat.

Subsequent Visits

Subjects returned 1, 3, and 9 months after baseline for safety visits to assess lactic acid, creatinine, CBC and ALT. At 6 months all measurements performed at baseline were repeated except MRI/MRS and cardiac CT. At 12 months a visit identical to the baseline visit occurred. Subjects were discontinued for creatinine >132.6µmol/L, ALT >2.5× ULN, lactic acid >2× ULN and hemoglobin <6.21mmol/L.

Biostatistical Analysis

Baseline variables were compared between the 4 groups by ANOVA for continuous variables and by x2 test for categorical variables. For outcomes that were not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. All data were included in the analysis by intention to treat principle. For subjects who did not complete a 12-month visit, last observation carried forward (LOCF) was performed for those subjects for whom interim data post the baseline visit was available. For the primary endpoint, calcium score, additional sensitivity analyses were performed carrying forward the baseline data on any patient who dropped out during the study as well as performing an analysis imputing change based on the median % change in each category among completers and transforming this to an absolute change imputed for those without 12-month data.

We first compared the change over time between metformin and placebo and LSM and no LSM, as per the 2×2 factorial design. These contrasts compared the change among all patients receiving LSM vs. those not, regardless of metformin/placebo assignment and separately the changes among all those receiving metformin vs. those receiving placebo, regardless of the LSM assignment. Prior to performing this analysis we tested for an interaction between the LSM assignment and metformin/placebo assignment. In addition, we determined the net effect of metformin (vs. placebo) controlling for the LSM randomization and the net effect of LSM (vs. no LSM) controlling for the metformin randomization in a factorial analysis. Change over 12 months was compared between the groups by ANOVA for normally distributed outcomes and by the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed outcomes.

We then compared the change over 12 months in each of the 4 groups: 1) no LSM, placebo; 2) LSM, placebo; 3) no LSM, metformin; 4) LSM, metformin, using all available data and carrying forward any interim data post baseline. The overall comparison was by ANOVA. For data that were not normally distributed, rank-based Kruskal-Wallis test was applied. If significant, post hoc testing between individual groups was performed. In the 4 group analysis, a test for linear trend was performed.

With 40 evaluable patients in each of the two factorial comparisons, we were able to detect a 1 SD or greater change from baseline difference between the groups with 85% power at alpha = 0.05. Pre-specified endpoints were changes in CAC score, cIMT as well as MS parameters. All results are reported as mean ± SEM, for those variables that are not normally distributed results are also reported as median (IQR).

Results

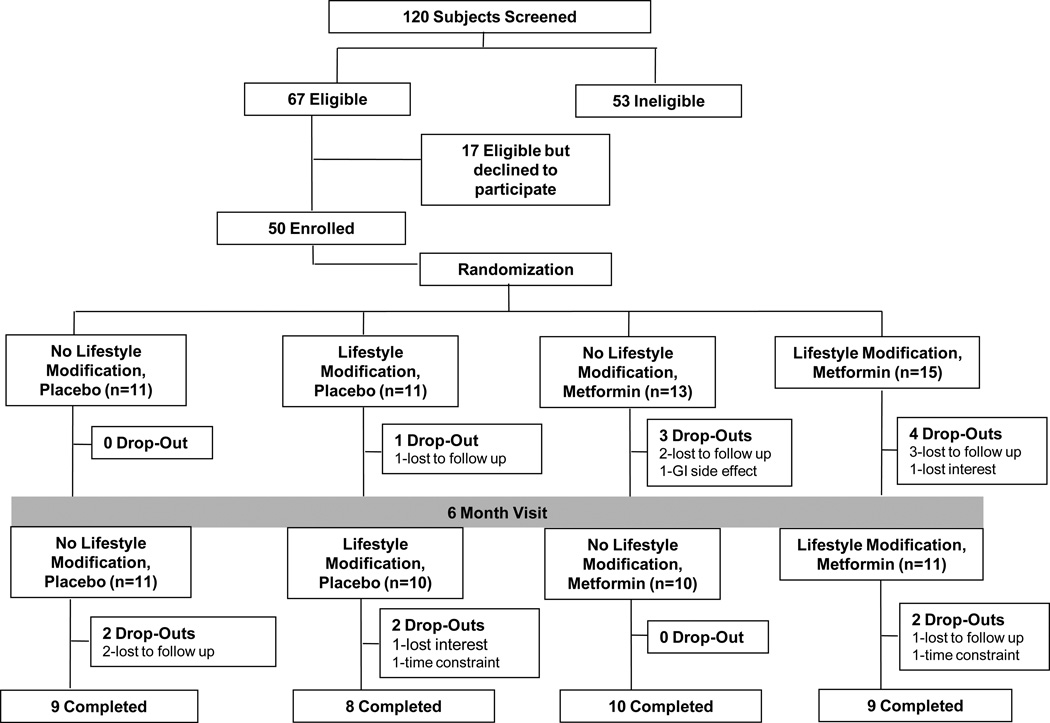

See Figure 1 for flow of participants through the study. Fourteen subjects withdrew for an overall dropout rate of 28% (Fig. 1). The dropout rates were not statistically significantly different between the groups in the factorial analysis metformin (32%) vs. placebo (23%) (P=0.46) and LSM (35%) vs. no LSM (21%) (P=0.28) or in the 4 group analysis (Fig 1). Forty-two subjects (84%) had evaluations at 6 months.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of subjects through the study.

At baseline there were no significant between group differences for age, race, gender, smoking status, or HIV parameters including CD4 count, HIV viral load, and duration of HIV infection or ART use. Duration of HIV infection was on average 14 ± 1 yr and duration of antiretroviral therapy was 6 ± 1 yr. HbA1c was 5.5±0.1%. There were no between group differences for baseline parameters (Table 1). CAC was > 0 in 51% of subjects, with similar percentages in the study groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic & Clinical Characteristics (n = 50)

| No Lifestyle Modification, Placebo (n=11) |

Lifestyle Modification, Placebo (n=11) |

No Lifestyle Modification, Metformin (n=13) |

Lifestyle Modification, Metformin (n=15) |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 47 ± 2 | 49 ± 2 | 45 ± 2 | 47 ± 2 | 0.79 |

| Race [n (%)] | 0.63 | ||||

| Caucasian | 7 (64) | 6 (55) | 9 (69) | 10 (67) | |

| African American | 4 (36) | 4 (36) | 3 (23) | 5 (33) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 7/4 | 8/3 | 10/3 | 13/2 | 0.59 |

| Current smoking [n (%)] | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | 3 (23) | 7 (47) | 0.42 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 35 ± 5 | 43 ± 5 | 38 ± 13 | 38 ± 5 | 0.95 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 80.4 ± 7.1 | 90.1 ± 4.4 | 90.1 ± 4.4 | 93.7 ± 4.4 | 0.26 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.28 |

| HIV Parameters | |||||

| CD4 cell count (#/mm3) | 583 ± 66 | 691 ± 129 | 406 ± 72 | 643 ± 57 | 0.07 |

| HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL, log10) | 1.94 ± 0.17 | 1.93 ± 0.14 | 2.33 ± 0.28 | 1.73 ± 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Duration HIV (years) | 16 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 15 ± 2 | 0.49 |

| Current PI Use [n (%)] | 7 (64) | 6 (55) | 6 (46) | 9 (60) | 0.83 |

| Current NRTI Use [n (%)] | 11 (100) | 9 (82) | 10 (77) | 13 (87) | 0.54 |

| Current NNRTI Use [n (%)] | 3 (27) | 1 (9) | 2 (15) | 5 (33) | 0.07 |

| Cardiovascular Parameters | |||||

| Calcium Score | 76 ± 40 [3 (0,67)] | 131 ± 64 [103 (0,214)] | 7 ± 5 [0 (0,6)] | 25 ± 13 [0 (0,28)] | 0.23 |

| Calcified Plaque Volume (mm3) | 68.8 ± 37.2 [1.4 (0.0,121.5)] | 101.5 ± 47.9 [86.3 (0.0,174.2)] | 9.9 ± 7.9 [0.0 (0.0,5.5)] | 22.7 ± 13.7 [0.0 (0.0,19.9)] | 0.28 |

| cIMT (mm) | 0.69 ± 0.05 [0.64 (0.57,0.82)] | 0.73 ± 0.04 [0.71 (0.60,0.87)] | 0.74 ± 0.05 [0.75 (0.57,0.82)] | 0.78 ± 0.06 [0.77 (0.60,0.94)] | 0.75 |

| Exercise Parameters | |||||

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 23.4 ± 1.0 | 22.1 ± 1.7 | 23.7 ± 0.9 | 22.1 ± 1.2 | 0.70 |

| Exercise duration (min) | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 0.11 |

| 1 RM Tricep dip (lbs) | 197 ± 19 | 169 ± 13 | 207 ± 18 | 229 ± 16 | 0.11 |

| 1 RM Knee flexor (lbs) | 126 ± 11 | 116 ± 8 | 147 ± 10 | 132 ± 8 | 0.15 |

| 1 RM Lateral pulldown (lbs) | 126 ± 14 | 111 ± 8 | 138 ± 8 | 127 ± 9 | 0.30 |

| 1 RM Knee extension (lbs) | 124 ± 12 | 114 ± 11 | 141 ± 9 | 143 ± 12 | 0.24 |

| 1 RM Chest press (lbs) | 99 ± 14 | 85 ± 8 | 105 ± 9 | 113 ± 10 | 0.30 |

| 1 RM Leg press (lbs) | 500 ± 59 | 430 ± 39 | 512 ± 45 | 539 ± 48 | 0.46 |

| Metabolic Syndrome Criteria | |||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100 ± 2 | 109 ± 2 | 104 ± 3 | 106 ± 4 | 0.24 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.90 ± 0.31 [1.64 (1.25,1.90)] | 2.03 ± 0.29 [2.02 (1.24,2.32)] | 2.33 ± 0.41 [1.85 (1.28,2.71)] | 2.51 ± 0.36 [2.17 (1.53,3.37)] | 0.57 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.98 ± 0.08 [0.91 (0.78,1.22)] | 0.93 ± 0.08 [0.83 (0.76,1.22)] | 0.96 ± 0.05 [0.93 (0.83,1.09)] | 0.91 ± 0.10 [0.80 (0.67,1.06)] | 0.58 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.27 ± 0.22 | 5.49 ± 0.17 | 4.89 ± 0.17 | 5.44 ± 0.17 | 0.06 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 121 ± 3 | 122 ± 4 | 125 ± 3 | 117 ± 4 | 0.56 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 ± 2 | 78 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | 75 ± 3 | 0.30 |

| Metabolic Parameters | |||||

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 0.50 |

| hsCRP (mg/L)* | 2.18 ± 0.68 [1.78 (0.44,2.87)] | 2.53 ± 1.04 [1.52 (0.32,2.86)] | 3.57 ± 1.00 [3.04 (0.73,4.99)] | 2.65 ± 0.74 [1.56 (0.93,3.28)] | 0.55 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.13 ± 0.51 [1.89 (1.38,2.41)] | 2.05 ± 0.57 [1.33 (0.47,3.38)] | 1.55 ± 0.25 [1.67 (0.64,2.24)] | 1.72 ± 0.45 [1.01 (0.15,3.32)] | 0.80 |

| PAI-1 (ng/mL) | 73.8 ± 15.3 [47.9 (36.0,126.4)] | 65.1 ± 14.2 [50.8 (41.8,67.0)] | 83.5 ± 10.9 [70.1 (60.7,102.9)] | 79.7 ± 14.8 [66.1 (44.9,86.9)] | 0.28 |

| Body Composition Parameters | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 0.9 | 30.1 ± 1.2 | 30.2 ± 1.2 | 31.6 ± 2.1 | 0.50 |

| VAT area (cm2) | 182.1 ± 23.3 | 198.1 ± 19.8 | 201.4 ± 32.1 | 185.1 ± 32.4 | 0.95 |

| SAT area (cm2) | 230.0 ± 41.3 | 333.3 ± 46.3 | 263.1 ± 39.6 | 220.1 ± 35.2 | 0.21 |

| Tibialis Anterior IMCL (mmol/kg) | 1.3 ± 0.2 [1.3 (0.9,1.8)] | 1.5 ± 0.2 [1.3 (1.0,1.9)] | 1.3 ± 0.3 [1.3 (0.6,2.0)] | 2.0 ± 0.4 [1.7 (1.0,2.5)] | 0.54 |

| Total Extremity Fat (kg) | 8.0 ± 1.3 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 0.58 |

Normally distributed data reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); P value by ANOVA

Non-normally distributed data reported also as [median (IQR)]; P value is by Kruskal-Wallis test

Data on two subjects with extreme values of CRP are not included, nor included in the change calculations. These data points met criteria for exclusion using the Dixon criteria at alpha > 0.99.

PI, protease inhibitor: NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; HDL, high density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; cIMT, carotid intima media thickness; BMI, body mass index; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; IMCL, intramyocellular lipid; RM, repetition maximum.

There were no differences between the groups for dietary parameters at baseline. For the entire cohort, caloric intake was 2253 calories/day, with 36% of calories from fat, 12% from saturated fat, 6% from polyunsaturated fat, and 14% from monounsaturated fat. Total daily fiber intake was 19g. Vitamin B12 intake was adequate at baseline (6.7±0.5 mcg/day) among the entire cohort and similar in the study groups.

Compliance

Among subjects completing the protocol, the compliance with lifestyle sessions (% of sessions attended) was 84±4% for the LSM, placebo group and 84±4% for the LSM, metformin group. Metformin compliance, determined by pill count, was 88±0%.

Effects of Lifestyle Modification and Metformin

Cardiovascular Parameters

Metformin treated subjects demonstrated significantly less progression of CAC than placebo-treated patients (−1±2 vs. 33±17, [0 (0,0) vs. 14 (0,34)] P=0.004, metformin vs. placebo) (Figure 2a). In contrast, CAC progression was not significantly different between LSM and no LSM groups (8±6 vs. 21±14, P=0.82, [6 (0,14) vs. 0 (0,14)] P=0.82, LSM vs. no LSM) Figure 2b. The corresponding % changes in calcium score were ([2 (−59,85) vs. 19% (5,77)] metformin vs. placebo and ([12 (−23,34) vs. 66% (−64,81)] LSM vs. no LSM. Metformin had a significantly greater effect on CAC than LSM (P=0.01). Metformin treated subjects also demonstrated significantly less progression in calcified plaque volume than placebo-treated patients (−0.4±1.9 vs. 27.6±13.8 mm3, P =0.008). In an additional sensitivity analysis using last observation carried forward from baseline for all non-completers in the study, metformin treated subjects similarly demonstrated decreased deterioration in CAC score (−0.7±1.4 vs. 25.6±13.6, P=0.004) and calcified plaque volume (−0.2±1.2 vs. 22.7±11.6 mm3, P=0.005) compared to placebo. Similar results were seen in a sensitivity analysis with imputed data based on median percent change among completers. In addition, metformin significantly prevented plaque progression in the subset with CAC > 0 at baseline (−3 ± 6 vs. 46 ± 23, P=0.003, metformin vs. placebo). No significant effects on calcified plaque volume or cIMT parameters were observed in the comparison of LSM vs. no LSM.

Figure 2.

a. Change from baseline in calcium score in placebo vs. metformin groups (P = 0.004) by Kruskal-Wallis test comparing change over 12 months between groups.

b. Change from baseline in calcium score in no lifestyle modification vs. lifestyle modification (P = 0.82) by Kruskal-Wallis test comparing change over 12 months between groups.

c. Change from baseline in calcium score in: 1) no lifestyle modification, placebo, 2) lifestyle modification, placebo, 3) no lifestyle modification, metformin; 4) lifestyle modification, metformin. Overall comparison between groups by ANOVA (P=0.03). Test for linear trend (P=0.03). P values for individual contrasts are shown using ranked contrasts.

In the 4 group analysis, a significant overall effect between the groups was seen for CAC (ANOVA P=0.03) (Table 2). A significant overall linear trend (P=0.03) was also seen demonstrating that CAC progression was greatest among the group receiving no LSM, placebo, in whom the change represented a median increase of 56% (−40,79), and smallest in the group receiving LSM, metformin (Figure 2c). Compared to the group receiving no LSM, placebo, the change over 12 months was significantly smaller in the group receiving LSM, metformin (P=0.03). In addition, CAC progression was significantly less in the group receiving no LSM, metformin than in the group receiving LSM, placebo (P=0.01) (Figure 2c). For calcified plaque volume, a similar pattern was seen. Average changes from baseline in cIMT were nearly zero in all four treatment arms, and the between-group comparisons were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Effects of Lifestyle Modification, Metformin or Both (Change from Baseline)

| No Lifestyle Modification, Placebo (n=11) (Group A) |

Lifestyle Modification, Placebo (n=10) (Group B) |

No Lifestyle Modification, Metformin (n=10) (Group C) |

Lifestyle Modification, Metformin (n=11) (Group D) |

P Value |

Linear Trend P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Parameters | ||||||

| CD4 cell count (#/mm3) | 119 ± 71 | 31 ± 33 | 52 ± 22 | −55 ± 45 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL, log10) | 0.04 ± 0.24 | −0.25 ± 0.20 | 0.07 ± 0.35 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.42 |

| Cardiovascular Parameters | ||||||

| Calcium Scored | 43 ± 30 [10 (0,49)] | 19 ± 7 [14 (10,29)] | 1 ± 1 [0 (0,2)] | −4 ± 6 [0 (−13,3)] | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Calcified Plaque Volume (mm3) | 35.2 ± 23.4 [9.9 (0.0,35.3)] | 17.6 ± 9.5 [10.7 (3.2,28.1)] | 0.5 ± 0.7 [0.0 (0.0,1.2)] | −1.6 ± 4.8 [0.0 (−9.3,4.1)] | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| cIMT (mm) | −0.02 ± 0.03 [0.00 (−0.05,0.05)] | −0.02 ± 0.04 [−0.03 (−0.12,0.07)] | 0.00 ± 0.01 [0.00 (−0.01,0.02)] | 0.03 ± 0.02 [0.02 (−0.03,0.08)] | 0.37 | 0.18 |

| Exercise Parameters | ||||||

| VO2max (ml/kg/min)b | −0.7 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | −1.3 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Exercise duration (min)c | −0.4 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | −0.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 0.006 | 0.17 |

| 1 RM Tricep dip (lbs)c | 14 ± 14 | 83 ± 30 | 14 ± 12 | 68 ± 10 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| 1 RM Knee flexor (lbs)c | 4 ± 9 | 74 ± 13 | 5 ± 3 | 66 ± 11 | <0.0001 | 0.04 |

| 1 RM Lateral pulldown (lbs)c | 3 ± 9 | 56 ± 15 | 3 ± 5 | 54 ± 10 | 0.0002 | 0.04 |

| 1 RM Knee extension (lbs)c | 1 ± 9 | 71 ± 18 | 7 ± 9 | 73 ± 10 | <0.0001 | 0.02 |

| 1 RM Chest press (lbs)c | 4 ± 8 | 41 ± 8 | 4 ± 3 | 27 ± 5 | 0.0003 | 0.30 |

| 1 RM Leg press (lbs)c | 0 ± 24 | 192 ± 42 | 22 ± 14 | 167 ± 32 | <0.0001 | 0.04 |

| Metabolic Syndrome Criteria | ||||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | −1.9 ± 1.4 | −0.1 ± 1.7 | 0.3 ± 2.0 | −1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | −0.18 ± 0.31 [0.12 (−0.16,0.40)] | −0.07 ± 0.35 [0.10 (−0.81,1.01)] | −0.03 ± 0.18 [−0.08 (−0.46,0.35)] | −0.63 ± 0.47 [−0.38 (−0.97,0.35)] | 0.77 | 0.39 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | −0.05 ± 0.03 [−0.08 (−0.10,0.03)] | 0.05 ± 0.03 [0.03 (−0.03,0.16)] | 0.00 ± 0.05 [−0.03 (−0.16,0.21)] | 0.10 ± 0.03 [0.10 (0.00,0.16)] | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | −0.39 ± 0.28 | 0.17 ± 0.17 | 0.11 ± 0.11 | −0.39 ± 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.96 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −5 ± 4 | −2 ± 6 | −2 ± 4 | −6 ± 4 | 0.85 | 0.97 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −3 ± 2 | 1 ± 4 | −2 ± 3 | −5 ± 4 | 0.61 | 0.57 |

| Metabolic Parameters | ||||||

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | −0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.83 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | −0.27 ± 0.66 [0.14 (−1.05,0.97)] | −1.19 ± 1.11 [0.00 (−0.69,0.21)] | 0.47 ± 0.60 [−0.07 (−0.89,1.91)] | −1.92 ± 0.93 [−0.45 (−2.12,−0.02)] | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| HOMA-IR*b | 0.74 ± 0.53 [0.41 (−1.05,2.33)] | 1.51 ± 0.65 [1.23 (0.20,2.69)] | 0.82 ± 0.50 [0.50 (−0.03,1.71)] | −1.00 ± 0.59 [−0.51 (−2.51,0.41)] | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| PAI-1 (ng/mL) | 17.3 ± 14.3 [11.2 (−12.6,41.7)] | 4.0 ± 14.3 [3.2 (−20.1,20.1)] | 28.3 ± 18.0 [20.6 (−15.5,56.4)] | −28.3 ± 20.0 [1.3 (−46.1,6.0)] | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| Body Composition Parameters | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | −1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| VAT area (cm2) | −22.6 ± 14.5 | −1.5 ± 14.0 | −28.2 ± 15.3 | −35.0 ± 27.7 | 0.63 | 0.48 |

| SAT area (cm2) | −27.5 ± 14.5 | 4.9 ± 20.0 | −25.1 ± 18.7 | −13.8 ± 9.0 | 0.48 | 0.79 |

| Tibialis Anterior IMCL (mmol/kg)a | 0.6 ± 0.2 [0.6 (0.2,0.9)] | −0.4 ± 0.2 [−0.3 (−0.8,−0.1)] | 0.8 ± 0.4 [0.5 (−0.1,0.9)] | 0.1 ± 0.2 [0.2 (−0.4,0.4)] | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| Total Extremity Fat (kg) | −0.3 ± 0.6 | −0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | −1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

Normally distributed data reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); P value by ANOVA

Non-normally distributed data reported also as [median (IQR)]; P value is by Kruskal-Wallis test

For cIMT, 1 RM tests, metabolic syndrome criteria, metabolic parameters, BMI, HIV viral load LOCF analysis used carrying forward last observation from 6 month visit for those who dropped after 6 months (n=42). For other variables analyses used available date in subjects who completed the study.

1 subject prematurely discontinued metformin prior to 12-month visit and 12-month data for HOMA-IR for this patient excluded from the analysis using the Dixon criteria for outlier analysis at alpha > 0.8.

p<0.05 A vs. B; B vs. C

p<0.05 A vs. D

p<0.05 A vs. D and B; B vs. C

p<0.05 A vs. D; B vs. C

HDL, high density lipoprotein; cIMT, carotid intima media thickness; BMI, body mass index; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; IMCL, intramyocellular lipid; RM, repetition maximum; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Exercise and Diet Parameters

LSM was associated with improvements compared to no LSM on VO2max, endurance (time on cycle ergometer), tricep dip, knee flexor, lateral pulldown, knee extension, chest press, and leg press (P<0.01 for all parameters) and this effect was also seen in the 4 group analysis (Table 2). There were no statistically significant effects of metformin for exercise parameters. Subjects in the LSM group reduced total calories from fat by −4±2 vs. 0±2 %, P=0.08 (LSM vs. no LSM) and increased total fiber by 7±4 vs. 1±2 g/day, P=0.08 (LSM vs. no LSM). Changes in saturated fat were −2±1 vs.-1±1%, P=0.39 (LSM vs. no LSM). Vitamin B12 intake remained adequate throughout the study in all groups (data not shown).

Metabolic Parameters

HDL improved in those randomized to LSM vs. no LSM (0.08±0.03 vs. −0.03±0.03mmol/L, P=0.03) and a significant trend was seen across the groups in the 4 group analysis. Metformin improved HOMA-IR (−0.09±0.43 vs. 1.10±0.41, P=0.05) compared to placebo. In the 4 group analysis, the improvement in HOMA-IR was most significant in the LSM, metformin group and a significant trend was seen across the groups (Table 2). LSM decreased hsCRP compared to no LSM (−1.57±0.70 vs. 0.08±0.45mg/L, P= 0.05). LSM also tended to improve PAI-1 compared to no LSM (−12.9±12.7 vs. 22.3±11.1ng/mL (P=0.06). No other significant changes were observed for metabolic parameters.

Body Composition Parameters

Intramyocellular lipid improved in those randomized to LSM compared to those no LSM (−0.13±0.16 vs. 0.68±0.23mmol/kg, P=0.005), but did not differ in the comparison of metformin vs. placebo. VAT decreased −31.6±15.2 cm2 in those randomized to metformin vs. −13.4±10.2 cm2 to placebo, although this difference was not significant. Extremity fat did not change significantly in response to LSM (−0.5±0.3 vs. −0.2±0.4 kg, P=0.46, LSM vs. no LSM) or metformin (−0.5±0.4 vs. −0.2±0.3 kg, P=0.49, metformin vs. placebo).

Immunological Factors

LSM had a small but significant effect to decrease CD4 compared to those not randomized to LSM (−15±30 vs. 84±36, #/mm3, P=0.04). This effect persisted when baseline CD4 count was adjusted for in the analysis of 12-month CD4 change between the LSM and no LSM groups. No effect of metformin on CD4 was seen. Viral load was not affected by randomization to either LSM or metformin (P>0.05 for both groups). Percent of subjects with detectable viral load was also not affected by LSM (P=0.14, LSM vs. no LSM) or metformin (P=0.80, metformin vs. placebo).

Safety

Two subjects in the LSM, metformin group experienced minor elevations in creatinine level after the 3 month visit which returned to within normal limits after a dose reduction to metformin 500mg twice daily. No patient in a metformin group demonstrated an elevated lactic acid level above the normal limit. One subject in the metformin group withdrew from the study due to gastrointestinal side effects. Five subjects in the metformin group reported gastrointestinal side effects from the study drug, necessitating a temporary hold of study drug and reduction to 500mg twice daily or 500mg once daily. No gastrointestinal distress was reported in the placebo-treated groups. Two participants in the LSM group experienced muscle strains related to the resistance training necessitating modification of weights. There were no significant differences between groups for ALT, creatinine or lactic acid (P>0.05). There were no serious adverse events and the LSM program was well tolerated.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the effects of LSM and metformin on atherosclerotic indices among HIV-infected patients. Our data demonstrate that metformin had a robust effect to prevent progression of CAC and calcified plaque volume while improving HOMA-IR over one year in HIV patients with MS. LSM had an effect to improve HDL, hsCRP and IMCL of the tibialis anterior, but demonstrated a lesser effect to prevent progression of CAC in this population.

Cardiovascular disease and diabetes are prevalent in HIV-infected patients [1, 18]. Modification of risk factors for these illnesses is an important element in the management of HIV-infection. The only approved treatment for metabolic changes in HIV-infected patients, tesamorelin, targets abdominal obesity, does not improve insulin resistance, and has not been assessed with respect to critical atherosclerotic indices. In this study, we assessed LSM, widely recommended, but little studied, as a treatment for metabolic abnormalities in HIV patients, and simultaneously assessed metformin, which is known to reduce insulin resistance in HIV-infected patients [19] and has been shown to reduce CVD events in non-HIV-infected patients (UKPDS) [20]. Moreover, metformin is widely available, has a long established safety record, and is inexpensive.

Coronary artery calcification score is a measure of atherosclerotic heart disease; elevated CAC scores signify a greater risk of predicted coronary heart disease [21, 22]. Several studies have evaluated CAC scores among HIV-infected patients. Fitch et al. [9] recently demonstrated that HIV-infected men with MS had significantly higher CAC scores compared with HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected controls. Similarly, Mangili et al. [23] found presence of CAC to be significantly more common among HIV-infected men and women with MS compared to HIV-infected individuals without MS.

We saw an effect of metformin to prevent a significant increase in CAC and calcified plaque volume over one year of follow up. We stratified for antiretroviral therapy use, which did not differ between groups. Compliance with the medication was good by pill count. Safety and tolerance were good.

The increase in CAC of 43 in patients receiving placebo without LSM is clinically significant and represents a median change of 56%. This data highlights the natural history of plaque progression over one year in HIV patients with MS. Recent data from the MESA study, showing a 26% increase in coronary events for a doubling of CAC [24], put this increase in context and suggest a significant increase in CVD risk based on progression of CAC in the untreated HIV population. These data extend the data of Guaraldi et al. [25] who demonstrated HIV infection was independently associated with a CAC score increase of ≥ 15%/year. The magnitude of this increase in CAC score shown in our study confirms the urgent need to develop effective therapies to prevent CVD in this group of patients and suggests that chronic use of metformin in this population might prevent significant coronary atherosclerosis if a similar degree of prevention was multiplied over several years. The effect of metformin on CAC was seen within the entire cohort and also among those subjects with demonstrated calcium at baseline. Indeed, the MESA study tells us that the participants who demonstrate any CAC are at higher risk for CVD [26]. Demonstration of a significant effect of metformin to prevent plaque progression by metformin in this subgroup is an important observation of our study. Future studies limiting enrollment to the group with demonstrated CAC at baseline will be important to perform to assess treatment effects in those at the highest risk.

One potential mechanism by which metformin could affect plaque progression is via AMP-kinase activation. AMPK has a distinct role to regulate fatty acid oxidation and cholesterol in the heart [27]. Also, activation of AMPK may phosphorylate and inhibit HMG-CoA reductase activity, reducing cholesterol levels [28], therefore some beneficial vaso- and cardio-protective effects that are more commonly recognized to be induced by statins may also be related to AMPK activation in vascular tissues.

In contrast to metformin’s effect to prevent progression of CAC and calcified plaque volume, we did not see a significant effect of metformin on cIMT, another measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. One possible explanation for this finding is that development and progression of atherosclerosis may occur via different mechanisms within the vasculature [29]. As a result, thickening of the carotid arteries and deposition of calcium in the coronary arteries may be influenced by different factors and represent different stages in the atherosclerotic process. For example, Mangili et al. [30] recently showed that progression of cIMT in the common carotid in HIV was related to age, waist circumference, triglycerides and insulin, whereas CAC progression was related more specifically to insulin resistance assessed. Metformin affects on insulin sensitivity may contribute in part to differential effects on cIMT and CAC, although further studies are needed to understand these relationships. We assessed the common carotid artery and it is possible that different results would have been seen had we assessed different segments, including the internal carotid and bifurcation, areas in which HIV infection has recently been shown to be more highly associated with increased cIMT [31, 32].

LSM had a lesser effect to prevent plaque progression than metformin. Although numerous studies have been performed assessing various LSM regimens in HIV patients, they differ in scope of intervention, target population, duration of treatment, and compliance achieved [33–38] and none, to our knowledge, have assessed the effects on CAC or atherosclerotic indices. In this study, we modeled our lifestyle program after the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) [39], and added a standardized aerobic and strength training component. Compliance was reasonable, even over one year of 3x/week sessions. Anticipated improvement in exercise parameters, including VO2max, duration of exercise, and all strength parameters were seen, demonstrating the efficacy of the exercise program. To our knowledge, the DPP did not assess whether LSM improved cIMT in their study. In the current study, we demonstrate that LSM had a beneficial effect on HDL-cholesterol, IMCL, hsCRP and tended to improve PAI-I, a marker of impaired fibrinolysis. We did not see an effect on triglyceride. These finding are in accordance with other studies evaluating LSM in this population [35, 40]. Although it is possible that a more rigorous LSM program would have resulted in better results on CAC and cIMT, the program we used is well established and did result in anticipated effects on exercise parameters and aerobic capacity as well as a number of metabolic parameters. Moreover there was no relationship between change in VO2max or other exercise parameters and cIMT or CAC.

Intramyocellular lipids are elevated [41–43] and have been associated with measures of insulin resistance in HIV-infected patients [43]. We are not aware of prior longer-term studies demonstrating an effect of LSM on IMCL in HIV-infected patients, and now show that LSM significantly reduces IMCL in this population.

Elevated CRP has been associated with risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease and has been found to be elevated among HIV-infected patients [44, 45]. Exercise may reduce markers of inflammation through inhibition of adipocytokine production via effects on skeletal muscle, endothelial cells, and the immune system. In our study, LSM significantly reduced CRP. This finding is similar to studies among non-HIV-infected patients evaluating LSM and CRP [46, 47]. Among HIV-infected patients Lindegaard et al. [35] found a significant effect of endurance training to decrease CRP while resistance training did not induce the same effect.

Our study has limitations but a number of strengths. The study is randomized, placebo-controlled and of a relatively long duration demonstrating a robust effect of metformin to prevent plaque progression. The study had adequate power to show a significant effect of metformin to reduce CAC and calcified plaque volume, but was relatively small in size and may have been underpowered to assess effects on secondary endpoints and to assess the effects of LSM, which were more modest than metformin. Moreover, the sample size may have limited our ability to determine differences in dropout rates. To minimize any effects of dropout, we performed sensitivity analyses carrying forward baseline data and imputing missing data and showed similar results. Despite these limitations, the study is the first to demonstrate the potential utility of metformin to prevent a very significant, progressive increase in calcified plaque progression among HIV-infected patients with MS. LSM and training was effective to increase fitness and improve selective metabolic indices, but did not prevent progression of atherosclerosis as much as metformin. Further studies are now needed to understand the mechanisms of metformin to prevent calcified plaque progression and to determine whether metformin, alone or in combination with other strategies, might reduce or prevent CVD events in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants in the study, the nurses and dieticians on the MGH General Clinical Research Center.

Funding: Funding was provided by NIH R01 DK49302 and by NIH M01-RR-01066 and 1 UL1 RR025758-01, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Grinspoon has received research funding from Theratechnologies and Bristol Meyers Squibb and consulted for Theratechnologies and EMD Serono, unrelated to this work.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures to make relative to this work.

References

- 1.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein D, Hurley LB, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Sidney S. Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coronary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:471–477. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200208150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Burtcel B, et al. Coronary Heart Disease in HIV-Infected Individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo J, Abbara S, Shturman L, Soni A, Wei J, Rocha-Filho JA, et al. Increased prevalence of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis detected by coronary computed tomography angiography in HIV-infected men. AIDS. 2010;24:243–253. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333ea9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samaras K, Wand H, Law M, Emery S, Cooper D, Carr A. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Using International Diabetes Foundation and Adult Treatment Panel III Criteria: Associations with insulin resistance, disturbed body fat compartmentalization, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypoadiponectinemia 10.2337/dc06-1075. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:113–119. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonfanti P, Giannattasio C, Ricci E, Facchetti R, Rosella E, Franzetti M, et al. HIV and metabolic syndrome: a comparison with the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:426–431. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318074ef83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worm SW, Friis-Moller N, Bruyand M, D'Arminio Monforte A, Rickenbach M, Reiss P, et al. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients: impact of different definitions of the metabolic syndrome. AIDS. 2010;24:427–435. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328334344e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Corcoran C, Rietschel P, Piecuch S, Basgoz N, et al. Metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and lipodystrophy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:130–139. doi: 10.1086/317541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitch K, Lo J, Abbara S, Ghoshhajra B, Shturman L, Soni A, et al. Increased Coronary Artery Calcium Score and Noncalcified Plaque among HIV-infected Men: Relationship to Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiac Risk Parameters. JAIDS. 2010;55:495–499. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181edab0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dube MP, Stein JH, Aberg JA, Fichtenbaum CJ, Gerber JG, Tashima KT, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of dyslipidemia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of the HIV Medical Association of the Infectious Disease Society of America and the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37:613–627. doi: 10.1086/378131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final report. Circulation. 2002:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan R, Kaufhold J, Hemphill LC, Lees RS, Karl WC. Anisotropic Edge-Preserving Smoothing in Carotid B-mod Ultrasound for Improved Segmentation and Intima-Media Thickness (IMT) Measurement. Computers in Cardiology. 2000;27:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abate N, Burns D, Peshock RM, Garg A, Grundy SM. Estimation of adipose tissue mass by magnetic resonance imaging: validation against dissection in human cadavers. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abate N, Garg A, Coleman R, Grundy SM, Peshock RM. Prediction of total subcutaneous abdominal, intraperitoneal, and retroperitoneal adipose tissue masses in men by a single axial magnetic resonance imaging slice. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:403–408. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Halpern EF, Jensen ME, Rosenthal DI, Palmer WE. Intramyocellular lipid quantification: repeatability with 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2005;236:609–614. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362041661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, Kingsley LA, Palella FJ, Riddler SA, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1179–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadigan C, Corcoran C, Basgoz N, Davis B, Sax P, Grinspoon S. Metformin in the treatment of HIV lipodystrophy syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:472–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Group UPDSU. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) Lancet. 1998;352:654–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folsom AR, Kronmal RA, Detrano RC, O'Leary DH, Bild DE, Bluemke DA, et al. Coronary artery calcification compared with carotid intima-media thickness in the prediction of cardiovascular disease incidence: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1333–1339. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: the St. Francis Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangili A, Jacobson DL, Gerrior J, Polak JF, Gorbach SL, Wanke CA. Metabolic syndrome and subclinical atherosclerosis in patients infected with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1368–1374. doi: 10.1086/516616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guaraldi G, Zona S, Orlando G, Carli F, Ligabue G, Fiocchi F, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1857–1860. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, DeFilippis AP, Blankstein R, Rivera JJ, Agatston A, et al. Associations between C-reactive protein, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular events: implications for the JUPITER population from MESA, a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:684–692. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60784-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyck JR, Lopaschuk GD. AMPK alterations in cardiac physiology and pathology: enemy or ally? J Physiol. 2006;574:95–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hardie DG. Role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the cellular stress response. Curr Biol. 1994;4:315–324. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanderLaan PA, Reardon CA, Getz GS. Site specificity of atherosclerosis: site-selective responses to atherosclerotic modulators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:12–22. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000105054.43931.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangili A, Polak JF, Skinner SC, Gerrior J, Sheehan H, Harrington A, et al. HIV infection and progression of carotid and coronary atherosclerosis: the CARE study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:148–153. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d4993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, Currier JS, Scherzer R, Biggs ML, et al. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009;23:1841–1849. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenz MW, Stephan C, Harmjanz A, Staszewski S, Buehler A, Bickel M, et al. Both long-term HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy are independent risk factors for early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yarasheski KE, Tebas P, Stanerson B, Claxton S, Marin D, Bae K, et al. Resistance exercise training reduces hypertriglyceridemia in HIV-infected men treated with antiviral therapy. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:133–138. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driscoll SD, Meininger GE, Lareau MT, Dolan SE, Killilea KM, Hadigan CM, et al. Effects of exercise training and metformin on body composition and cardiovascular indices in HIV infected patients. AIDS. 2004;18:465–473. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindegaard B, Hansen T, Hvid T, van Hall G, Plomgaard P, Ditlevsen S, et al. The effect of strength and endurance training on insulin sensitivity and fat distribution in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3860–3869. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelson ES, Agin D, Kenya S, Werber-Zion G, Luty B, Albu JB, et al. Body composition and metabolic effects of a diet and exercise weight loss regimen on obese, HIV-infected women. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental. 2006;55:1327–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mutimura E, Crowther NJ, Cade TW, Yarasheski KE, Stewart A. Exercise training reduces central adiposity and improves metabolic indices in HAART-treated HIV-positive subjects in Rwanda: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:15–23. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balasubramanyam A, Coraza I, Smith EO, Scott LW, Patel P, Iyer D, et al. Combination of Niacin and Fenofibrate with Lifestyle Changes Improves Dyslipidemia and Hypoadiponectinemia in HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy: Results of "Heart Positive," a Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2236–2247. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:623–634. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitch KV, Anderson EJ, Hubbard JL, Carpenter SJ, Waddell WR, Caliendo AM, et al. Effects of a lifestyle modification program in HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome. AIDS. 2006;20:1843–1850. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000244203.95758.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Barlow RB, Librizzi J, Dolan S, Grinspoon S. Increased intramyocellular lipid accumulation in HIV-infected women with fat redistribution. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:609–614. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00797.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gan SK, Kriketos AD, Poynten AM, Furler SM, Thompson CH, Kraegen EW, et al. Insulin action, regional fat, myocyte lipid: altered relationships with increased adiposity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1295–1305. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luzi L, Perseghin G, Tambussi G, Meneghini E, Scifo P, Pagliato E, et al. Intramyocellular lipid accumulation and reduced whole body lipid oxidation in HIV lipodystrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E274–E280. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00391.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samaras K, Gan SK, Peake PW, Carr A, Campbell LV. Proinflammatory markers, insulin sensitivity, and cardiometabolic risk factors in treated HIV infection. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:53–59. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Triant VA, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of C-reactive protein and HIV infection with acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:268–273. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a9992c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jae SY, Fernhall B, Heffernan KS, Jeong M, Chun EM, Sung J, et al. Effects of lifestyle modifications on C-reactive protein: contribution of weight loss and improved aerobic capacity. Metabolism. 2006;55:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldhammer E, Tanchilevitch A, Maor I, Beniamini Y, Rosenschein U, Sagiv M. Exercise training modulates cytokines activity in coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.