Abstract

Background

A cornerstone of a surgeon’s clinical assessment of suitability for major surgery is best described as the “eyeball test”. Pre-operative imaging may provide objective measures of this subjective assessment by calculating a patient’s morphometric age. Our hypothesis is that morphometric age is a surgical risk factor distinct from chronologic age and comorbidity and correlates with surgical mortality and length of stay.

Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study within a large academic medical center. Using novel analytic morphomic techniques on pre-operative CT scans, a morphometric age was assigned to a random sample of patients having inpatient general and vascular abdominal surgery during 2006–2011. The primary outcomes for this study are post-operative mortality (1-year) and length of stay (LOS).

Results

The study cohort (N=1370) was stratified into tertiles based on morphometric age. The postoperative risk of mortality was significantly higher in the morphometric old age group when compared to the morphometric middle age group (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.52 – 3.84, p<0.001). Morphometric old age patients were predicted to have a 4.6 day longer LOS than the morphometric middle age tertile. Similar trends were appreciated when comparing morphometric middle and young age tertiles. Chronologic age correlated poorly with these outcomes. Furthermore, patients in the chronologic middle age tertile found to be of morphometric old age had significantly inferior outcomes (mortality 21.4% and mean LOS 13.8 days) compared to patients in the chronologic middle age tertile found to be of morphometric young age (mortality 4.5% and mean LOS 6.3 days, p<0.001 for both).

Conclusions

Preoperative imaging can be used to assign a morphometric age to patients, which accurately predicts mortality and length of stay.

Introduction

When considering a patient for major surgery, surgeons rely on clinical instinct to judge a patient’s likelihood of a successful outcome. Patient age is often a central factor in this assessment, but may not accurately represent a patient’s overall health, as reflected by often used phrases such as “the patient looks older (younger) than his/her stated age”. While validated risk stratification tools exist to assist surgeons, these tools typically only evaluate one portion of the patient’s operative risk (e.g. cardiovascular health) and are only helpful in cases where patients have advanced comorbid disease. Therefore, a surgeon’s clinical decision-making is largely subjective and difficult to communicate to patients and other clinicians. Better objective measures of preoperative risk are needed.

Underlying a surgeon’s subjective patient assessment, often referred to as the “eyeball test”, is primarily a visual assessment of the patient’s physical appearance relative to their stated age. Physical changes that occur with age have previously been well documented and are associated with functional and clinical health outcomes (1–4). Furthermore, recent work has shown strong relationships between patient age, patient morphometric characteristics on preoperative imaging, and surgical outcomes following surgery (5–13). Moreover, data in pre-operative images in may inform perioperative risk assessments and add objectivity to the “eyeball test”.

With this work, we propose a new paradigm: utilizing preoperative imaging studies to quantitatively assess whether a patient is morphometrically younger or older than their stated age. This will provide an objective global assessment of the patient that is intuitive to clinicians and patients. Our previous work has identified 3 morphometric measures that strongly correlate with surgical outcomes and advancing age (trunk muscle size, trunk muscle density, and vascular calcification) (5–10). In this study, we use a population of kidney donor and trauma patients to determine the baseline morphometric characteristics of aging. Then, for each study patient having major surgery, we use their morphometric characteristics to assign a morphometric age as calibrated by our reference population. Our hypothesis is that morphometric age is a surgical risk factor distinct from chronologic age and comorbidity and correlates with surgical mortality and length of stay.

Methods

Analytic morphomics

Our previous work has described these methods in detail (5–10). In brief, individual vertebral levels were first identified on each patient’s CT scan. The cross-sectional area and average density, in Hounsfield Units (HU), of the left and right psoas muscles at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra (L4) were measured.

Abdominal aortic (AA) calcification was measured in the wall of the infrarenal aorta. The center of the aorta was manually located at the inferior aspect of the L1 vertebrae. The centerline and radius of the aorta were defined from this imaging slice to the inferior aspect of the L3 vertebrae. To adjust for differences in contrast, the density of the aortic lumen, in Hounsfield Units (HU), was used to define the minimum window level. Calcification was selected in a semi-automatic fashion, as a group of pixels between 3 and 2000 pixels contained in the aortic wall, with HU at least 25% greater than HU of the aortic lumen. Manual adjustments were made to capture all calcification. Given the limitations of this calcification algorithm, patients with aortic disease were excluded. AA calcification was expressed as percentage of the total wall area containing calcification.

All analytic morphomic procedures were completed using custom algorithms programmed in MATLAB® v13.0 (MathWorks®, Natick, MA). All algorithm outputs were visually confirmed by an image processor.

Patient Populations

Control population

The baseline morphometric characteristics of aging were determined using a pool of control patients. We selected two patient populations as controls: individuals approved as kidney donors at the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) (N=1624) and a random sample of trauma patients treated at UMHS (N=1689). Kidney donors are deemed healthy by a surgeon and nephrologist prior to receiving a CT scan, and trauma patients likely represent a reasonable cross section of the healthy general population. These groups were selected as controls because they were thought to best represent a patient and clinician’s perception of “normal” aging. The inclusion period for the control patients was 2000 to 2010.

Study Population

Our study population was comprised of patients in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) database who underwent major inpatient general and vascular surgery at UMHS and had a CT scan of the abdomen specifically for preoperative planning (within 90 days prior to the surgical event) from 2006 to 2011 (N=1370). The MSQC database represents a prospectively collected and random sample of surgical patients. The specific methods for patient selection, data collection, and data definitions have been well described previously by our group and others (14–17). Data were collected on the over 30 preoperative risk factors which are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of the Study Population (n=1,370) Stratified by Tertiles of Chronologic Age

| Chronologic tertile, mean ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Youngest | Middle | Oldest | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| n | 456 | 457 | 457 |

| Age, y | 36.9 ± 8.8 | 55.7 ± 4.1 | 71.6 ± 6.6 |

| Height, cm | 170.6 ± 10.6 | 171.7 ± 10.4 | 168.7 ± 11.0 |

| Weight, kg | 83.1 ± 24.5 | 86.6 ± 24.2 | 80.7 ± 19.8 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.6 ± 8.3 | 29.3 ± 7.9 | 28.3 ± 6.4 |

| Preoperative albumin, g/dL | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Male sex | 46.7 (213) | 55.8 (255) | 55.1 (252) |

| Non-white race | 19.5 (89) | 16.2 (74) | 12.9 (59) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9.6 (44) | 16.6 (76) | 28.0 (128) |

| Smoker | 18.6 (85) | 19.7 (90) | 9.8 (45) |

| Non-independent functional status | 5.0 (23) | 7.2 (33) | 10.1 (46) |

| COPD | 2.2 (10) | 3.9 (18) | 6.8 (31) |

| Recent transient ischemic attack | 0.9 (4) | 0.4 (2) | 3.9 (18) |

| Cancer diagnosis, n (%) | 5.5 (25) | 9.4 (43) | 7.2 (33) |

| Currently receiving radiotherapy | 0.4 (2) | 3.7 (17) | 5.0 (23) |

| Currently receiving chemotherapy | 2.6 (12) | 5.9 (27) | 4.8 (22) |

| Taking preoperative steroids | 10.1 (46) | 8.8 (40) | 7.9 (36) |

| Preoperative sepsis | 11.2 (51) | 6.6 (30) | 6.3 (29) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.7 (3) | 2.8 (13) | 2.8 (13) |

| Ascites | 1.8 (8) | 0.9 (4) | 1.3 (6) |

| Case mix characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Emergent priority | 16.2 (74) | 10.7 (49) | 9.8 (45) |

| Liver resection | 3.3 (15) | 4.8 (22) | 5.0 (23) |

| Pancreatic resection | 3.7 (17) | 11.2 (51) | 14.9 (68) |

| Major vascular | 5.3 (24) | 5.0 (23) | 7.0 (32) |

| Other general surgery | 87.7 (400) | 79.0 (361) | 73.1 (334) |

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures for this study were mortality within one year of the index surgical event and length of stay (LOS). Mortality was ascertained by referencing the Social Security master death index. Length of stay was calculated from admission to discharge.

Determining Morphometric Age

Morphometric age was modeled within the control population using a multivariable linear regression model. For these models the dependent variable was morphometric age and the independent variables included previously validated morphometric characteristics (psoas area, psoas density, and percent wall aortic calcification). Separate models were created for men and women, as we have described previously (7,10).

There were some important differences between the control and study populations with respect to chronologic age and gender distribution. To address this issue, control patients were selected for inclusion using a SAS Greedy Matching algorithm (based on chronologic age and gender in a 1:1 fashion). The morphometric age models were then applied to each study population patient in order to determine morphometric age.

As a sensitivity analysis, morphometric age was also determined utilizing an alternative method. Instead of using matching algorithms for the control and study populations, mean morphometric measures for control patients of the same chronologic age and gender was calculated. Morphometric age was then modeled using this control population (separate models for genders) and the model subsequently used for the study patients to determine their morphometric age. All analyses were repeated using this second method with negligible differences in outcomes and no differences in conclusions. As a result, the initial method of determination of morphometric age is reported.

Outcomes Analyses

Continuous variables were compared using a t-test and Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. The relationship between burden of comorbid disease, morphometric age, and chronological age were further assessed. Patients were assigned a point for each comorbid condition collected by the MSQC. Three groups of patients were selected: the 10% oldest chronologic age, the 10% oldest morphometric age, and the 10% with the most comorbidities. These groups were compared using a Venn diagram.

In order to determine whether chronologic and morphometric age were independently associated with the mortality and LOS, multivariable logistic and linear regression was performed using stepwise backward selection to identify a set of model covariates from the candidate variables previously detailed. Each patient was assigned into a tertile for both chronologic age and morphometric age. Separate models were created for chronologic age (mortality and LOS) and morphometric age (mortality and LOS). For the logistic models, the reference age population was the middle tertile and the outputs are expressed as odds ratios [OR] ± 95% confidence interval [95%CI] compared to the middle tertile group.

The implications of age adjustment were then assessed by comparing patients of the same chronologic age group, but who “jumped” into older and younger age groups after morphometric age adjustment. First, we compared outcomes among patients from the middle chronologic age group who jumped either to the young or the old morphometric age group. Next, we compared the outcomes of patients from the youngest chronologic age group who jumped to the oldest morphometric age group and the patients from the oldest chronologic age group who jumped into the youngest morphometric age group. These comparisons used a t-test or Fischer’s exact test.

All analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (Cary, NC). A two-sided significance of α = 0.05 was used for all analyses. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent for subjects.

Results

The control population

The mean chronologic age of this group was 41.1 ± 14.8 years and 54.7% were male. The mean psoas muscle area for men was (3266.3 ± 725.1 mm2) and for women was (1919.7 ± 447.2 mm2). The mean psoas muscle density for men was (57.1 ± 7.5 HU) and for women was (54.5 ± 7.4 HU). The mean percent aortic wall calcification for men was (2.5 ± 7.3 %) and for women was (1.9 ± 6.8 %). There was a linear relationship between chronologic age and mean psoas muscle area for men (y = −20.69x + 4098.4, r = −0.43) and for women was (y = −12.84x + 2461, r = −0.41). There was a linear relationship between chronologic age and mean psoas density for men (y = −0.23x + 66.24, r = −0.46) and for women was (y = −0.17x + 61.55, r = −0.32). There was a linear relationship between age and aortic calcification for men (y = 0.26x - 7.96, r = 0.54) and for women was (y = 0.21x −7.23, r = 0.46). A linear regression model for morphometric age (covariates included total psoas area, psoas density, and aortic calcification) resulted in the following equation for men (Age = 87.56 - 0.006*TPA - 0.397*psoas density + 0.588*calcification, r = 0.67, p<0.001 for all covariates) and for women (Age = 93.39 −0.012*TPA - 0.461*psoas density + 0.62*calcification, r = 0.64, p<0.001 for all covariates).

The study population

Patients in the study group (N=1370) were separated into 3 groups based on chronologic age (youngest, middle, oldest chronologic age groups). Descriptive and clinical characteristics for these groups are detailed in Table 1. For the study group overall, case mix included: 60 liver cases (4.4%), 79 major vascular cases (5.8%), 136 pancreas cases (9.9%) and 1095 cases categorized as “other” major general surgery (79.9%). The chronologic oldest patients were 55.1% male, had an average BMI of 28.3 kg/m2, an average albumin of 3.8 g/dL, and an average age of 71.6 years. 10.1% of these patients were functionally non-independent, 7.9% were taking steroids preoperatively, and 6.3% had preoperative sepsis.

Patients were also separated into 3 groups based on morphometric age (youngest, middle, oldest morphometric age groups), and their descriptive and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The morphometric oldest patients were 57.5% male, had an average BMI of 27.7 kg/m2, an average albumin of 3.6 g/dL, and an average chronologic age of 65.3 years. 16.6% of these patients were functionally non-independent, 12.7% were taking steroids preoperatively, and 12.0% had preoperative sepsis.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics of the Study Population (n=1370) Stratified by Tertiles of Morphometric Age

| Morphometric tertile, mean ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Youngest | Middle | Oldest | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| n | 456 | 457 | 457 |

| Age, y | 44.2 ± 13.6 | 54.9 ± 13.4 | 65.3 ± 12.5 |

| Height, cm | 169.6 ± 10.9 | 171.5 ± 10.2 | 169.8 ± 11.0 |

| Weight, kg | 86.3 ± 25.4 | 84.0 ± 22.5 | 80.0 ± 20.5 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.1 ± 8.8 | 28.5 ± 7.0 | 27.7 ± 6.6 |

| Preoperative albumin, g/dL | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.8 |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Male sex | 40.8 (186) | 59.3 (271) | 57.5 (263) |

| Non-white race | 19.1 (87) | 17.7 (81) | 11.8 (54) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10.1 (46) | 16.6 (76) | 27.6 (126) |

| Smoker | 15.4 (70) | 14.4 (66) | 18.4 (84) |

| Non-independent functional status |

1.3 (6) | 4.4 (20) | 16.6 (76) |

| COPD | 1.3 (6) | 3.9 (18) | 7.7 (35) |

| Recent transient ischemic attack |

0.2 (1) | 2.0 (9) | 3.1 (14) |

| Cancer diagnosis, n (%) | 5.3 (24) | 8.3 (38) | 8.5 (39) |

| Currently receiving radiotherapy |

2.2 (10) | 3.3 (15) | 3.7 (17) |

| Currently receiving chemotherapy |

2.9 (13) | 5.0 (23) | 5.5 (25) |

| Taking preoperative steroids | 5.0 (23) | 9.0 (41) | 12.7 (58) |

| Preoperative sepsis | 4.6 (21) | 7.4 (34) | 12.0 (55) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.4 (2) | 1.5 (7) | 4.4 (20) |

| Ascites | 0.4 (2) | 1.5 (7) | 2.0 (9) |

| Case mix characteristics | |||

| Emergent priority | 12.1 (55) | 9.2 (42) | 15.5 (71) |

| Liver resection | 4.6 (21) | 4.2 (19) | 4.4 (20) |

| Pancreatic resection | 8.3 (38) | 11.8 (54) | 9.6 (44) |

| Major vascular | 3.3 (15) | 5.0 (23) | 9.0 (41) |

| Other general surgery | 83.8 (382) | 79.0 (361) | 77.0 (352) |

We then investigated the relationship between chronologic age, preoperative comorbidities, and morphometric age. We compared the 10% of patients with the greatest morphometric age to the 10% of patients with the greatest chronologic age and the largest number of preoperative comorbidities. (Figure 1) We note that 57.2% of patients within the group with the oldest morphometric age were not in the oldest chronologic age group. Similarly, 73.0% of patients within the group of the oldest morphometric age were not in the group with the most medical comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Morphometric age as an independent domain of surgical risk. Red circle, the 10% oldest patients by morphometric age; green circle, the 10% oldest patients by chronological age; blue circle, the 10% with the most comorbidities. Note that 57.2% of patients within the group with the oldest morphometric age were not in the oldest chronologic age group. Similarly, 73.0% of patients within the group of the oldest morphometric age were not in the group with the most medical comorbidities.

Mortality analysis

We then compared chronologic and morphometric age as independent risk factors for postoperative mortality. Independent of other covariates, morphometric age is a better predictor of mortality than chronological age (area under ROC curve [AUROC] = 0.75 vs. AUROC = 0.63). Per one year increase, the odds of mortality increase 1.06 times (p<0.001, 95%CI: 1.04 – 1.07) for morphometric age compared to OR =1.03 for chronologic age (p <0.001, 95%CI: 1.02 – 1.05). When stratifying patients into tertiles of age and using the middle group for comparison, the chronological oldest patients were not at significantly greater risk of mortality than the middle age patients (p = 0.11, OR = 1.39, 95%CI: 0.93 – 2.07). The chronological youngest patients did have significantly less mortality risk than the middle age patients (p = 0.002, OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.26 – 0.73). The morphometric oldest had significantly greater mortality risk than the middle age group (p <0.001, OR = 3.30, 95%CI: 2.16 – 5.06) while the morphometric youngest group had significantly less mortality risk (p = 0.002, OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.16 – 0.66).

For multivariable analysis, the comparison group was also the middle age group. The risk of postoperative mortality was significantly smaller for the chronological youngest group compared to the chronological middle age group (OR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24 – 0.79, p = 0.009). Conversely, patient in the oldest chronologic age group did not have a significantly higher mortality in patients in the middle chronologic age group (OR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.86 – 2.15, p = 0.19). When inputted as a continuous variable, chronologic age was statistically significant (p<0.001, OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.02 – 1.05). Other significant covariates in this model include emergent priority status (p = 0.003, OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.33 – 3.89), dialysis (p<0.001, OR = 4.41, 95%CI: 1.98 – 9.86), non-White race (p = 0.006, OR = 0.36, 95%CI: 0.17 – 0.74), cancer (p<0.001, OR = 3.01, 95%CI: 1.66 – 5.47), albumin (p<0.001, OR = 0.51 per g/dL, 95%CI: 0.38 – 0.69), operation time (p<0.001, OR = 1.17 per hour, 95%CI: 1.07 – 1.27), dyspnea (p = 0.001, OR = 2.35, 95%CI: 1.39 – 3.97), bleeding (p = 0.016, OR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.15 – 3.96), steroid use (p = 0.02, OR = 1.99, 95%CI: 1.11 – 3.55), chemotherapy (p = 0.001, OR = 3.38, 95%CI: 1.65 – 6.93), non-independent functional status (p = 0.035, OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.05 – 3.67). The AUROC for this model was 0.84. After adjusting for covariates, the mortality rate of the chronologic oldest patients was 14.0% compared to 4.8% for the chronologic youngest patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Covariate-adjusted 1-year mortality rates stratified by tertiles of morphometric and chronologic age. Blue bar, chronologic age; red bar, morphometric age. Mortality was adjusted for the covariates listed in Table 3, determined by logistic regression. Morphometric age was a significant predictor of 1-year mortality, while chronologic age was not. The morphometric youngest had half the risk of 1-year mortality compared to the chronologic youngest, while the morphometric oldest had greater risk than the chronologic oldest.

The risk of postoperative mortality was significantly smaller for the morphometric youngest group compared to the morphometric middle age group (OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.23 – 0.98, p = 0.045). In addition, patients in the oldest morphometric age group had a significantly higher mortality than patients in the middle morphometric age group (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.52 – 3.84, p<0.001). As a continuous variable, morphometric age remained a significant predictor (p<0.001, OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.02 – 1.05). The results of this multivariable model are summarized in Table 3. The AUROC for this model was 0.83. After adjusting for covariates, the mortality rate of the morphometric oldest patients was 19.9% compared to 2.4% for the morphometric youngest patients (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Covariates for 1-Year Mortality and Morphometric Age

| Covariate | p Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphometric age (reference = Middle Group) | ||

| Youngest Tertile | 0.044 | 0.47 (0.23 – 0.98) |

| Oldest Tertile | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.52 – 3.84) |

| Emergent Status | 0.003 | 2.18 (1.30 – 3.64) |

| Dialysis | 0.002 | 3.16 (1.53 – 6.55) |

| Cancer | <0.001 | 3.90 (2.24 – 6.77) |

| Dyspnea | <0.001 | 2.44 (1.49 – 4.00) |

| Bleeding disorder | 0.008 | 2.22 (1.24 – 3.99) |

| Albumin per g/dL | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.41 – 0.71) |

| Operation time per h | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06 – 1.25) |

LOS analysis

We then compared chronologic and morphometric age as independent risk factors for LOS. Independent of other covariates, morphometric age is a better predictor of LOS than chronological age (Pearson-product moment correlation coefficient = 0.27 vs. 0.09). For multivariable analysis, age was stratified into tertiles. Chronological age was not a significant predictor of LOS (p = 0.30, β = 0.43 per tertile). Chronologic age remained insignificant as a continuous variable (p = 0.20, β = 0.03 per year). Significant covariates included RVU (p = 0.04, β = 0.10 per unit), dyspnea (p = 0.023, β = 2.52), ventilator dependency (p = 0.005, β = 6.36), pneumonia (p = 0.024, β = 9.03), ascites (p<0.001, β = 10.72), CHF (p = 0.009, β = 7.86), acute renal failure (p = 0.036, β = 7.73), sensorium (p = 0.001, β = 14.07), bleeding (p<0.001, β = 5.76), sepsis (p = 0.021, β = 3.38), PVD (p = 0.008, β = 5.83), albumin (p<0.001, β = −3.88 per g/dL), operation time (p<0.001, β = 1.01 per hour), non-independent functional status (p = 0.01, β = 4.15), and contaminated or dirty wound classification (p<0.001, β = 3.96). The overall correlation coefficient for this model was 0.59. The covariate-adjusted LOS was then computed for each tertile. The chronologic oldest patients adjusted LOS was 11.3 days compared to 8.5 days for the chronologic youngest (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Covariate-adjusted length of stay stratified by tertiles of morphometric and chronologic age. Blue bar, chronologic age; red bar, morphometric age. Length of stay was adjusted for the covariates listed in Table 4, determined by linear regression. Patients in the youngest morphometric tertile were predicted to have shorter LOS than those in the youngest chronologic tertile, while patients in the oldest morphometric tertile were predicted to have longer LOS than the chronologic oldest patients.

Morphometric age was a significant predictor of LOS (p = 0.032, β = 0.93 per tertile) in the presence of other covariates. Thus, holding all other model covariates equal, a patient in the oldest tertile would be predicted to have a 1.86 day longer LOS than a patient in the youngest tertile. Morphometric age remained a significant predictor as a continuous variable (p = 0.002, β = 0.09 per morphometric year). The overall correlation coefficient for this model was 0.60. The results of the multivariable models are summarized in Table 3. The covariate-adjusted LOS for the morphometric oldest patients was 14.2 days compared to 5.8 days for the morphometric youngest patients (Figure 3).

Clinical implications of morphometric age adjustment

We then assessed the clinical implications of morphometric age adjustment on patients within the chronologic middle tertile. Patients in the chronologic middle age tertile but who jumped into the old morphometric age group had significantly inferior outcomes (mortality 21.4% and mean LOS 13.8 days) compared to patients in the chronologic middle age tertile but who jumped into the morphometric young group (mortality 4.5% and mean LOS 6.3 days, p<0.001 for both comparisons). (Figure 4a) There was no significant difference in chronologic age or case mix complexity (23.5 vs. 23.8 RVU, p = 0.82) among patients in the chronologic middle tertile who jumped into the morphometric oldest and morphometric youngest groups, respectively.

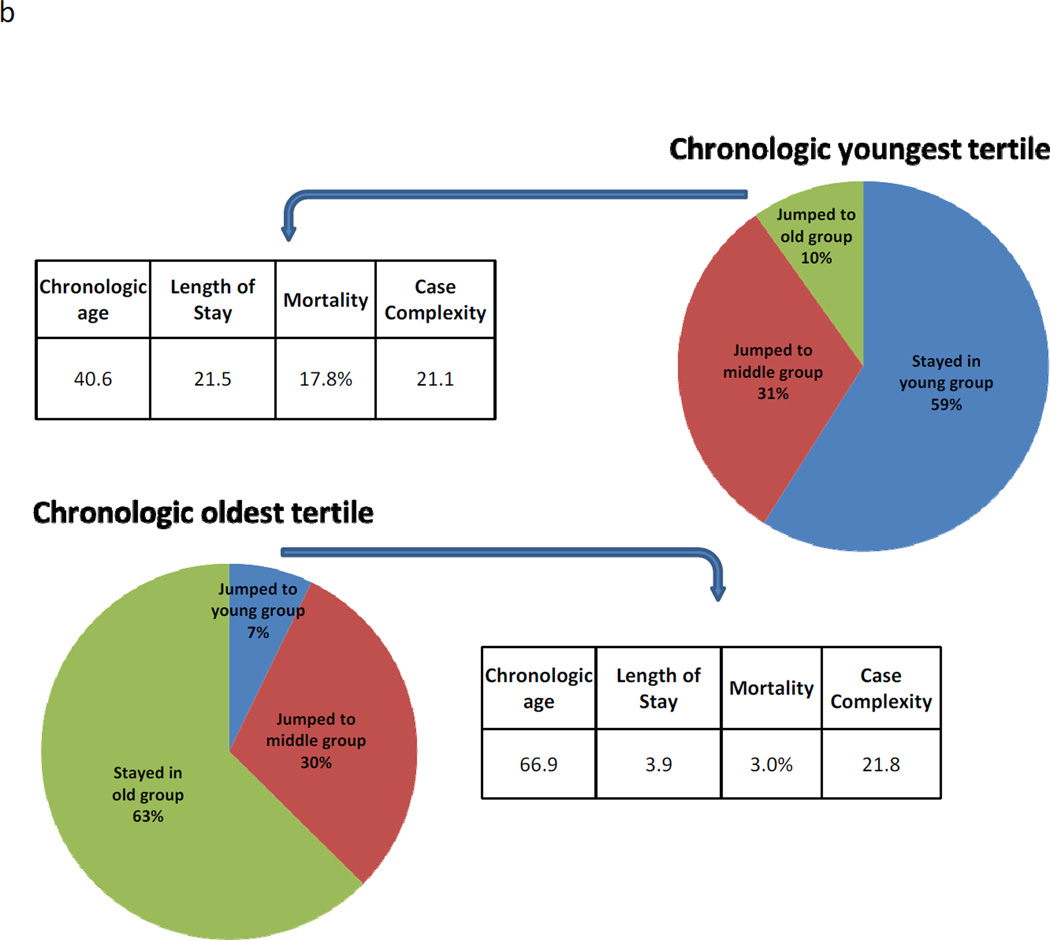

Figure 4.

(A) The clinical implications of morphometric age adjustment on patients within the chronologic middle tertile. Patients in the chronologic middle age tertile but who jumped into the old morphometric age group had remarkably inferior outcomes (mortality 21.4%) compared to patients in the chronologic middle age tertile but who jumped into the morphometric young group (mortality 4.5%, p<0.001). Note there was no significant difference in the patients who jumped with respect to chronologic age and case complexity. (B) Patients in the chronologic youngest tertile (mean age 40.6 y) but morphometric oldest tertile had poor surgical outcomes, including a mortality rate of 17.8%. Conversely, patients in the chronologic old tertile (mean age 66.9 y) but the morphometric young tertile had good surgical outcomes, including a mortality of 3.0% (p<0.001).

Patients in the chronologic youngest tertile (mean age 40.6) but morphometric oldest tertile had poor surgical outcomes, including a mortality rate of 17.8% and a mean LOS of 21.5 days. (Figure 4b) Conversely, patients in the chronologic oldest tertile (mean age 66.9) but the morphometric youngest tertile had good surgical outcomes, including a mortality of 3.0% and the mean LOS of 3.9 days (p<0.001 for both comparisons). Measures the case complexity were similar between the two groups (21.1 vs. 21.8, p = 0.81).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that cross-sectional imaging can be used to assign a morphometric age to surgical patients. Morphometric age appears distinct from chronologic age and comorbidity. Morphometric age appears to be more strongly associated than chronologic age with the outcomes of one-year mortality and LOS. Patients who “jump” from young to old when comparing morphometric age to chronologic age appear to have particularly poor postoperative outcomes, with one-year mortality of approximately 20%. In contrast, chronologically older patients who are morphometrically young have a low risk of mortality and a shorter LOS.

This study suggests that cross sectional imaging can be used to reliably assess morphometric changes associated with aging. Furthermore, preoperative imaging can be used to assign a morphometric age to patients, which more accurately predicts surgical morbidity and mortality than chronologic age. The techniques used in this study, specifically quantitative analysis of medical imaging data called “analytic morphomics”, represent a novel approach to the assessment of preoperative risk. Our impression is that this assessment of a patient’s physical condition may provide an objective metric that supports the surgeon’s subjective assessment of fitness for surgery, imitating the “eyeball test”. Further, expressing this assessment as “age” provides an intuitive risk measure for clinicians and patients.

It is well established that older patients have inferior surgical outcomes (18 – 20). Underpinning these inferior outcomes are discrete physiologic changes associated with aging, including muscle loss and increased atherosclerosis. Previous work has demonstrated that these physiologic changes can be accelerated in chronic disease states, have been correlated with overall survival and functional status, and may be associated with postoperative mortality (2,3,10). Certainly, all clinicians appreciate the wide variation in physiologic reserve among older patients and many older patients do very well, even following the most physiologically demanding surgical procedures. Similarly, our work has demonstrated wide variation in morphometric changes of aging. This fact enables this novel measure to identify relatively low-risk older patients, as well as high-risk younger patients.

When a clinician comments that patient appears “older than stated age”, one envisions a frail patient who would be high risk for a major surgical procedure. It is certainly too simple of an approach to distill the complex physiologic changes of aging into 3 simple morphometric measures. Alternatively, we could have described the relationship between each morphometric characteristic and surgical outcome, without filtering these risk factors into a single variable related to the patient age. We have chosen to express morphometric patient characteristics as age in order to leverage the unique characteristics of age has an intuitive perioperative risk factor for patients and clinicians. Additional work is needed to elucidate additional morphometric characteristics, determine how best to communicate morphometric risk assessment to patients and clinicians, and more broadly how preoperative imaging can inform clinical decision-making.

There are some important limitations of this work. First, not all patients get a preoperative cross-sectional imaging study. Further, this study is retrospective and involves patients from a single center and is not designed to attribute causality between morphometric age and poor surgical outcomes. In addition, the best methods to determine morphometric age are debatable. We have chosen a cohort of kidney donors and trauma patients as a “healthy” patient population to serve as the reference population for the “normal” morphometric changes of aging. Including patients with acute or chronic illness being assessed for surgical intervention in our reference population may or may not have improved the generalizability of our morphometric age assessment.

Overall, this study demonstrates the potential benefit of quantifying morphometric age and emphasizes the rich source of additional data contained in preoperative imaging studies. Better understanding the complex milieu of preoperative risk factors offers opportunities for improved risk stratification and informs shared decision-making between patients and surgeons. Further, analytic morphomics may elucidate mechanisms of adverse surgical outcomes, informing novel approaches to mitigate these risks. Unlike standard risk factors, morphometric measures available on the preoperative imaging may highlight potentially remediable preoperative risks. For example, low core muscle size may identify patients who will benefit from pre-operative strength training. Preoperative imaging may also reveal previously unappreciated surgical risk such as patients with no known cardiovascular risk factors but significant AA calcification. It is possible that in time surgeons will use imaging studies as a routine part of the preoperative evaluation of fitness for surgery.

Table 4.

Linear Regression Model Covariates for Length of Stay and Morphometric Age

| Covariate | p Value | Coefficient, β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphometric age tertile | 0.032 | 0.93 (0.08 – 1.78) |

| Operative Complexity (measured as RVU) | 0.005 | 0.09 (0.03 – 0.16) |

| Dyspnea | 0.031 | 2.38 (0.22 – 4.55) |

| Ventilator dependency | 0.004 | 6.55 (2.14 – 10.96) |

| Pneumonia | 0.026 | 8.87 (1.07 – 16.67) |

| Ascites | <0.001 | 10.75 (5.13 – 16.37) |

| CHF | 0.010 | 7.70 (1.85 – 13.54) |

| Acute renal failure | 0.037 | 7.67 (0.46 – 14.89) |

| Impaired sensorium | <0.001 | 13.92 (8.04 – 19.79) |

| Bleeding disorder | <0.001 | 5.58 (2.95 – 8.21) |

| Sepsis | 0.018 | 3.44 (0.59 – 6.29) |

| PVD | 0.012 | 5.58 (1.25 – 9.92) |

| Albumin per g/dL | <0.001 | −3.61 (−4.69 to −2.52) |

| Operation time per h | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.64 – 1.39) |

| Non-independent functional status | 0.016 | 3.91 (0.75 – 7.08) |

| Wound classification, contaminated or dirty/infected | <0.001 | 3.91 (2.04 – 5.78) |

| Constant | <0.001 | 13.53 (8.25 – 18.81) |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The 0 will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Financial support: Dr Englesbe is supported by NIH – NIDDK (K08 DK0827508) and the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

References

- 1.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried TR, Mor V. Frailty and hospitalization of long-term stay nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:265–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watters JM, Clancey SM, Moulton SB, et al. Impaired recovery of strength in older patients after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 1993;218:380–390. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199309000-00017. discussion 390-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Englesbe MJ, Patel SP, He K, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harbaugh C, Terjimanian MN, Lee JS, et al. Abdominal aortic calcification and surgical outcomes in patients with no known cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Surg. 2012 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826ddd5f. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JS, He K, Harbaugh CM, et al. Frailty, core muscle size, and mortality in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JS, Terjimanian MN, Tishberg LM, et al. Surgical site infection and analytic morphometric assessment of body composition in patients undergoing midline laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabel MS, Lee J, Cai S, et al. Sarcopenia as a prognostic factor among patients with stage III melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3579–3785. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englesbe M, Lee JS, He K, et al. Analytic morphomics, Core Muscle Size, and Surgical Outcomes. Ann Surg. 2012;256:255–261. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826028b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieffers JR, Bathe OF, Fassbender K, et al. Sarcopenia is associated with postoperative infection and delayed recovery from colorectal cancer resection surgery. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:931–936. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agnew SP, Small W, Jr, Wang E, et al. Prospective measurements of intra-abdominal volume and pulmonary function after repair of massive ventral hernias with the components separation technique. Ann Surg. 2010;251:981–988. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d7707b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng P, Hyder O, Firoozmand A, et al. Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1478–1486. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1923-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell DA, Jr, Englesbe MJ. How can the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program help or hinder the general surgeon? Adv Surg. 2008;42:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell DA, Jr, Kubus JJ, Henke PK, et al. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative: a legacy of Shukri Khuri. Am J Surg. 2009;198:S49–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englesbe MJ, Dimick JB, Sonnenday CJ, et al. The Michigan surgical quality collaborative: will a statewide quality improvement initiative pay for itself? Ann Surg. 2007;246:1100–1103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c3fe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Englesbe MJ, Pelletier SJ, Magee JC, et al. Seasonal variation in surgical outcomes as measured by the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) Ann Surg. 2007;246:456–465. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814855f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer JD. Operative mortality with elective surgery in older adults. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarborough JE, Pappas TN, Bennett KM, Lagoo-Deenadayalan S. Failure-to-pursue rescue: eplaining excess mortality in elderly emergency general surgical patients with preexisting "do-not-resuscitate" orders. Ann Surg. 2012;256:453–461. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826578fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Kelz RR, et al. Medical and financial risks associated with surgery in the elderly obese. Ann Surg. 2012;256:79–86. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825375ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]