Abstract

The structure of nucleosomes that contain the cenH3 histone variant has been controversial. In budding yeast, a single right-handed cenH3/H4/H2A/H2B tetramer wraps the ∼80-bp Centromere DNA Element II (CDE II) sequence of each centromere into a ‘hemisome’. However, attempts to reconstitute cenH3 particles in vitro have yielded exclusively ‘octasomes’, which are observed in vivo on chromosome arms only when Cse4 (yeast cenH3) is overproduced. Here, we show that Cse4 octamers remain intact under conditions of low salt and urea that dissociate H3 octamers. However, particles consisting of two DNA duplexes wrapped around a Cse4 octamer and separated by a gap efficiently split into hemisomes. Hemisome dimensions were confirmed using a calibrated gel-shift assay and atomic force microscopy, and their identity as tightly wrapped particles was demonstrated by gelFRET. Surprisingly, Cse4 hemisomes were stable in 4 M urea. Stable Cse4 hemisomes could be reconstituted using either full-length or tailless histones and with a 78-bp CDEII segment, which is predicted to be exceptionally stiff. We propose that CDEII DNA stiffness evolved to favor Cse4 hemisome over octasome formation. The precise correspondence between Cse4 hemisomes resident on CDEII in vivo and reconstituted on CDEII in vitro without any other factors implies that CDEII is sufficient for hemisome assembly.

INTRODUCTION

Centromeres are defining features of eukaryotic chromosomes, and yet exactly what defines a centromere has remained a matter of intense debate (1,2). In most eukaryotes, centromeres are epigenetically defined by the presence of special centromeric nucleosomes, in which the cenH3 histone variant replaces histone H3 in the nucleosome core (3). CenH3 (CENP-A in mammals, Cse4 in yeast and CID in Drosophila) is both necessary and sufficient for recruiting the other structural components of the kinetochore. Therefore, a central question in centromere biology is: What makes a cenH3 nucleosome different from an H3 nucleosome?

Various models for the cenH3 nucleosome have been proposed, including left-handed octameric nucleosome core particles (‘octasomes’) similar to conventional (H3/H4/H2A/H2B)2 octasomes (4), right-handed half-nucleosomes (‘hemisomes’) (5), homotypic (cenH3/H4)2 ‘tetrasomes’ that lack H2A/H2B dimers (6) and mixed octasomes containing both cenH3 and H3 (7). Several lines of evidence favor the existence of cenH3 hemisomes at centromeres. Arrays of cenH3 nucleosomes have been isolated and characterized from Drosophila and human cells and shown to have the dimensions, composition and other features of hemisomes (8–10). Further characterization of these particles has been hampered by the fact that centromeres of most eukaryotes are embedded in highly repetitive satellite DNA sequences that have been refractory to genetic and molecular analysis. In contrast, all 16 budding yeast centromeres are defined by ∼120-bp Centromere DNA Elements (CDEs), each of which is occupied by a single Cse4 nucleosome (11). In vivo DNA topology measurements have shown that the Cse4-containing particles induce positive DNA supercoils, which implies a right-handed DNA wrap around the Cse4 core, opposite to the left-handed wrap of conventional H3 nucleosomes and inconsistent with an octasome model (12). Mapping of all 16 yeast centromeres at base-pair resolution has shown that Cse4 is confined to the ∼80-bp CDEII sequence, only enough DNA for a single wrap around the core, and is flanked by distinct particles occupying CDEI and CDEIII (13), which are occupied respectively by the Cbf1 protein and the CBF3 complex. Furthermore, all 16 yeast centromeres were found to contain uniform amounts of H2A (13), and quantitative fluorescence imaging of kinetochore clusters detected only one Cse4 molecule per centromere over the large majority of the cell cycle (14), consistent with the singly wrapped particle being a Cse4/H4/H2B/H2A hemisome. Yeast Cse4 can support segregation of human chromosomes (15), suggesting that the cenH3 hemisome is the universal unit of centromere identity.

The case for left-handed cenH3 octasomes at centromeres is primarily based on several studies in which stable octasomes, but not hemisomes, have been readily produced by reconstitution using human or yeast histones (4,6,16–21). Although Drosophila CID particles induce positive DNA supercoils (12), both human and yeast particles induce negative supercoils (17,19,22), consistent with a conventional left-handed wrap. A high-resolution structure of the left-handed human CENP-A octasome shows that the histone core superimposes well with the H3 octasome (16), and the essentiality of key positions in the cenH3:cenH3 dimerization interface (4,23) support the notion that cenH3 octasomes are biologically important. Evidence for octasome formation in vivo has also been reported. When Cse4 is mildly overproduced in budding yeast, octasome-sized particles misincorporate into chromosome arms, especially at sites of high nucleosome turnover (13), and it appears that high-level expression of Drosophila CID can also produce octasomes (23). Although hemisomes are found at centromeres during most of the cell cycle, octasomes have been detected as transient intermediates during replication (10). The possibility that octasomes are transient forms is also consistent with the finding that cenH3 octasomes are partially unwrapped (16,17,19,20) and therefore are inherently less stable than H3 octasomes. Further evidence that cenH3 octasomes detected in vivo are likely to be unstable is that several groups have reported that Cse4 octasomes either do not form efficiently with yeast centromeric DNA (4,6,17,18) or form unstable octasomes that dissociate on short-term storage (17). In contrast, reconstitution on either an inverted repeat of human α-satellite or the ‘Widom 601’ nucleosome positioning sequence (24) yielded stable Cse4 octasomes (17). Therefore, the observation of Cse4 octasomes in vivo is supported by the in vitro assembly data; however, Cse4 hemisome formation at centromeres in vivo has not been corroborated by in vitro evidence, leaving open the question as to whether Cse4 hemisomes are inheritantly unstable (1,22).

The failure to reproduce in vivo findings by applying traditional in vitro reconstitution methods to assemble cenH3 nucleosomes has led us to examine the behavior of Cse4 and H3 octamer core particles under varying salt and urea concentrations, both in the absence and presence of DNA. We find that Cse4 octamers are far more resistant to dissociation than are H3 octamers, which implies that the H4/H2B interface that holds together the Cse4/H4/H2B/H2A hemisome is exceptionally stable. Standard in vitro reconstitution methods were developed for efficient production of octasomes and have so far failed to produce hemisomes in vitro. We have adopted an alternative nucleosome reconstitution method (25) and show that it produces Cse4 and H3 hemisomes that are remarkably stable, even in 4 M urea. Using this method, we have produced stable hemisomes that are identical in sequence and composition to hemisomes that have been mapped to the yeast genome, thus fully reconciling in vitro and in vivo observations. Moreover, the exceptional stability of hemisomes in the absence of flanking DNA demonstrates that non-histone proteins are not required to hold the yeast Cse4 nucleosome together and provides a mechanistic explanation for the evolution of stiff CDEII DNA as an adaptation that favors hemisomes over octasomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparing nucleosome core particles

Sets of four Saccharomyces cerevisiae histones [(H3, Cse4, Cse4-Δ90 or Cse4-Δ129) plus H4, H2A and H2B] were coexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity (Supplementary Figure S1A) by heparin and size exclusion chromatography to yield soluble H3 and Cse4 octamers as previously described (19). See Supplementary Materials and Methods for details on preparing DNAs.

Nucleosome core particles were reconstituted by mixing equimolar amounts of DNA and histone octamers in 2 M NaCl, followed by dialysis against 1 × Tris-Acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer, except as indicated. Equimolar refers to two duplexes per octamer (or one duplex per hemimer) for short duplexes (62–78 bp) and one duplex per octamer for 147-bp DNA. Preparation of trypsinized cores followed the protocol of (26), in which digestion was controlled by timed exposure of octamer cores to trypsin-agarose beads (Sigma T4019-25UN), followed by two rounds of centrifugation to remove the beads. Histones were visualized by either Coomassie or silver staining.

Aliquots of DNA duplexes were diluted in 2 M NaCl and mixed with histone octamers on ice to ∼5 µM in 10–40 µl volumes and dialyzed at least 4 h into a low-salt or urea-containing buffer. In some experiments, dialysis units were transferred after dialysis in low-salt buffer to 4 M urea solutions. We often observed more aggregation with gradient dialysis; therefore, we routinely used a one-step method.

Size exclusion chromatography of histone complexes

Octameric complexes of either H3 or Cse4-Δ129 were purified by preparative Superdex 200 chromatography in 2 M NaCl. Monodisperse peak fractions were pooled and aliquots fractionated on an analytical Superdex 200 GL column equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and varying amounts of NaCl (2, 0.8, 0.5 M). Samples in 2 M NaCl were injected into the column, and rapid dissociation of octameric complexes into smaller subcomplexes was assayed. To test the stability of histone octamers containing either H3 or Cse4-Δ129, the column was equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 M NaCl, and with or without 2 M urea.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Histone octamers containing either H3 or Cse4-Δ129 were dialyzed against buffers containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and either 150 or 500 mM NaCl. Samples were spun at 50 000 rpm at 20°C in ProteomeLab XL-I (Beckman) using interference detection optics. SEDFIT (27) was used to perform the concentration distribution [c(s)] analysis using direct Lamm equation fitting of the sedimentation boundary to calculate the concentration distribution [c(s)] and molecular weight (MW) of sedimenting species.

Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was performed on Cse4 and H3 particles in parallel. Samples were fixed with 0.6% glutaraldehyde for 25 min at room temperature, diluted 1:200 (1 mM EDTA), deposited onto APTES [(3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane]-mica as described (28) for 40 min, rinsed with Nanopure water and dried under an argon stream. Imaging was carried out in Acoustic AC Mode with a 5500 SPM (Agilent Technologies, http://www.agilent.com) using silicon-nitride probes (Agilent Technologies) with a nominal stiffness of 48 N/m, resonance frequency of 190 kHz and an amplitude setting between 2.5 and 3.0 V. The scanning rate was 1.514 Hz. For each sample, 150 particles were counted. Particle heights were measured using Gwyddion data analysis software (http://gwyddion.net). A maximum height was taken as the peak height relative to the local background. We used an internal DNA duplex standard (145 or 147 bp 601 DNA) to obtain reproducible height measurements and to compare between samples. This provided a check on precisely where the mica surface is: by measuring heights of DNA and particles on the same surface, we could use the average ‘bottom’ of all measurements for both. Heights measured by AFM differ from crystallographic values because of sample compression and uncertainty about the baseline owing to adsorbed salts. AFM experiments and measurements were performed without prior knowledge of the biochemical findings described in this study.

RESULTS

Cse4 octamers resist dissociation in low-salt and denaturing conditions

To explain why H3 forms octasomes and Cse4 forms hemisomes in vivo but both form octasomes in vitro, we considered the possibility that the high salt, histone and DNA concentrations used in typical reconstitution protocols favor the formation of larger particles with more histone–DNA contacts. We reasoned that in the absence of DNA, inherent stability differences between H3 and Cse4 particles might be more readily detected. When fully assembled H3 octamers in 2 M NaCl are dialyzed to reduce the salt concentration, they dissociate into (H3/H4)2 tetramers and H2A/H2B dimers (29), and we wondered whether the same would be the case for Cse4 octamers. To test this possibility, we first produced octamers containing either H3 or Cse4-Δ129 (deleted for the N-terminal tail) by simultaneously expressing all four histones in E. coli, where they spontaneously fold into soluble octamers in vivo (19). Cse4-Δ129 was used because the long N-terminal tail of Cse4 caused aggregation at lower salt concentrations (data not shown). Soluble histone octamers produced in E. coli were purified in 2 M NaCl (see Supplementary Figure S1A), which promotes hydrophobic interactions among histones. Protein octamers were then size fractionated by analytical Superdex 200 gel-filtration chromatography at varying salt concentrations. We observed monodisperse peaks for both H3 and Cse4-Δ129 in 2 M NaCl and confirmed by SDS–PAGE analysis that all four histone were present in equimolar amounts (Figure 1A and B). As expected, H3 octamers size fractionated in 0.8 M NaCl showed partial dissociation into (H3/H4)2 tetramers and H2A/H2B dimers, and dissociation was complete at 0.5 M NaCl. In contrast, Cse4-Δ129 octamers showed little evidence of dissociation in 0.5 M NaCl, with no evidence of H2A/H2B dimer release. SDS–PAGE analysis confirmed that all four histones were present at approximately equimolar amounts in each protein-containing fraction. We conclude that salt conditions that cause H3 octamers to dissociate completely into (H3/H4)2 tetramers and H2A/H2B dimers do not result in release of H2A/H2B dimers from Cse4-Δ129 octamers.

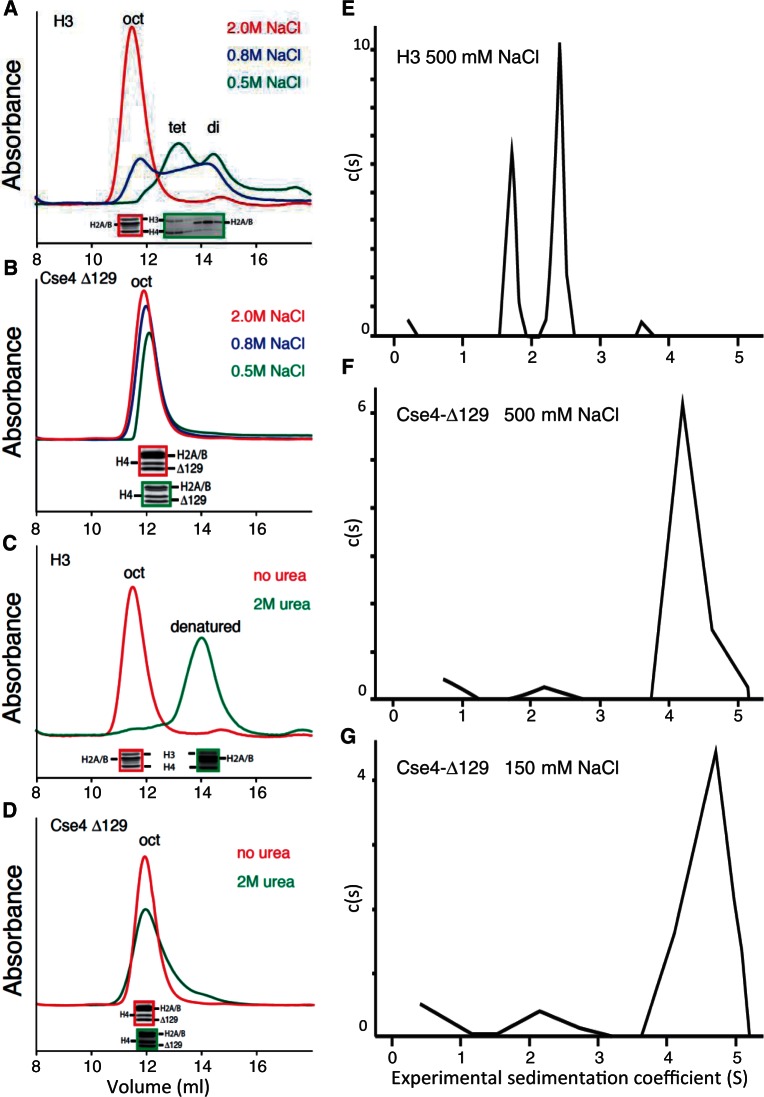

Figure 1.

Cse4 octamers resist dissociation in low-salt and denaturing conditions. (A and B) Superdex 200 gel-filtration chromatography of octamers containing (A) H3 or (B) (tail-deleted) Cse4-Δ129 following equilibration of the column with 2.0 (red), 0.8 (blue) or 0.5 M (green) NaCl. (C and D) Same as (A and B) except that the column was equilibrated with either 2 M NaCl (red) or 2 M NaCl + 2 M urea (green). Red- and green-bordered insets show SDS–PAGE Coomassie-stained images of corresponding peak fractions. In each panel, exactly the same sample was injected into the column; however, non-specific absorption to the column increases with lower salt concentrations, resulting in slightly lower recovery of total proteins. (E–G) Sedimentation velocity analyses of octamers containing H3 in 500 mM NaCl (E), Cse4-Δ129 in 500 mM NaCl (F) or Cse4-Δ129 in 150 mM NaCl (G).

We next size fractionated octamers by Superdex 200 chromatography equilibrated in 2 M urea + 2 M NaCl. These conditions completely denatured H3 octamers (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S2), whereas Cse4-Δ129 octamers remained intact (Figure 1D). Full-length Cse4 octamers also remained mostly intact in 2 M urea + 2 M NaCl (see Supplementary Figure S3). We conclude that H2A/H2B dimers are more tightly bound to (Cse4/H4)2 tetramers than they are to (H3/H4)2 tetramers.

To confirm the dissociation behavior of histone octamers containing either H3 or Cse4-Δ129 by an independent method, we analyzed histone octamers equilibrated to 0.5 M NaCl by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation. In 0.5 M NaCl, H3 octamers yielded two major sedimenting species (Figure 1E), consistent with the faster sedimenting species being (H3/H4)2 tetramers and the slower sedimenting species being H2A/H2B dimers, respectively. In contrast, Cse4-Δ129 octamers in 0.5 M NaCl sedimented as a single species, consistent with it being an intact octamer (Figure 1F).

Sedimentation velocity analysis also allowed us to test octamer particle stability under physiological salt conditions, 150 mM NaCl, which is too low to prevent adsorption to gel filtration matrices. Surprisingly, when analyzed by analytical centrifugation, the vast majority of Cse4-Δ129-containing octamers remained intact (Figure 1G). This failure of Cse4 octamers to dissociate under conditions typically used for in vitro assembly can potentially explain why only CenH3 octasomes were observed in multiple studies using DNA supercoiling to assay assembly (17,19,22).

Production of H3 and Cse4 hemisomes by splitting pseudo-octasomes

The standard protocol for reconstitution of octasomes in 2 M NaCl was developed to stabilize the histone complex while competing for electrostatic interactions between the highly basic histone core and the highly acidic DNA. This allows the productive binding of intact histone octamers to 147 bp of DNA but is unsuitable for reconstituting hemisomes. Moreover, the high stability of Cse4 octamers would further disfavor the production of hemisomes of the type observed in vivo (13). To eliminate inherent biases against hemisomes, we adopted an alternative assembly method introduced by Tatchell and van Holde (25): Octamers wrapped by two short DNA molecules (‘Pseudo-octasomes’) are assembled using ∼65-bp duplexes, with one duplex wrapping one half of the octamer and another duplex wrapping the other half, leaving a gap at the dyad axis. In support of this interpretation, they showed by sedimentation analysis that the pseudo-octasome becomes transformed into smaller particles, presumably hemisomes, as the ionic strength decreases. To our knowledge, this elegant protocol for producing hemisomes has never been used since.

Nucleosome structures indicate that a 62-bp DNA duplex will fully wrap a hemisome, and therefore we used the 62-bp sequence derived from human α-satellite (α62), which corresponds to the first 62 bp of the inverted repeat that has been used in most structural studies of nucleosomes (30). To assay for assembly, we followed a native gel-shift protocol, which yields a homogeneous band for 147-bp control octasomes produced by conventional salt dialysis of a mixture containing H3 octamers and Widom 601 duplexes (Figure 2A, left). Under similar conditions, a mixture of Cse4 octamers and α62 duplexes yielded a single moderately sharp band migrating at 680 bp on a native 6% gel (Figure 2B, left), whereas a mixture of H3 octamers and α62 duplexes consistently yielded two major gel-shifted products (Figure 2C, left).

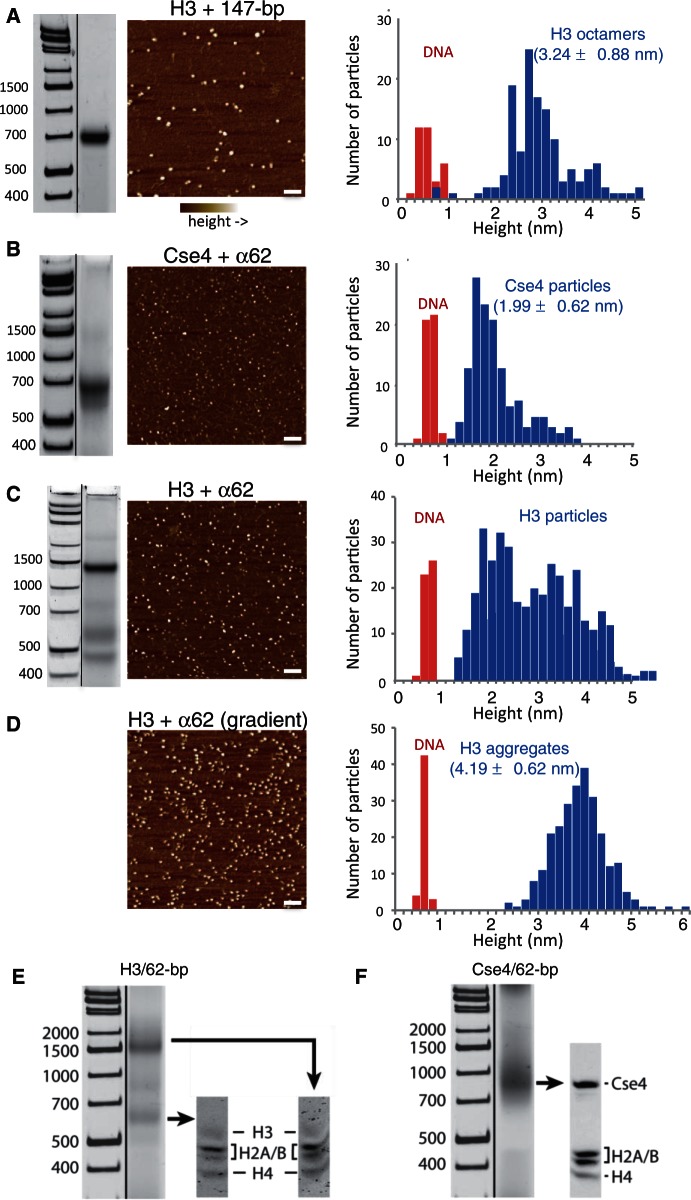

Figure 2.

Pseudo-octasomes split in half during low-salt dialysis. (A) Gel-shift image (native 7% PAGE), AFM image and height distribution of control H3 octamers assembled with 147-bp Widom 601 duplex DNA. (B) Same as (A) except using Cse4/α62 particles (native 6% PAGE). (C) Same as (A) except using H3/α62 particles (native 6% PAGE). In (A–C), DNA standards are included only as a rough guide, as migration of nucleosomal particles varies depending on gel concentration and running conditions. (D) AFM image and height distribution of H3 particles produced by gradient dialysis from 2 to 0.25 M, followed by step dialysis to 0.25 mM, conditions that increase aggregation. Bar in each image = 100 nm. DNA duplexes (147-bp 601) added to each sample provided an internal height standard. (E and F) Gel-shifted bands contain all four histones. Bands from native 6% gels were excised as indicated and loaded onto an SDS–PAGE gel to determine the histone composition of the particles. Particles were assembled using (E) H3 or (F) Cse4.

To obtain an absolute determination of particle sizes from these samples, we analyzed them by AFM, which can sensitively measure particle heights. We observed two distinct size classes of particles in the H3/α62 sample and one in the Cse4/α62 sample (Figure 2A and B). When compared with internal DNA standards, their median heights were estimated to be 2.2 nm for the smaller H3 particles, ∼3–5 nm for the larger H3 particles (Figure 2C) and 2.0 nm for the Cse4 particles (Figure 2B). Based on previous AFM measurements of heights for reconstituted tetrameric (2.5 nm) and octameric (3.7 nm) nucleosome particles (31), we tentatively conclude that the larger H3 gel-shifted particles are pseudo-octasomes or larger and that the smaller gel-shifted H3 particles and the Cse4 particles are hemisomes. We found that by using gradient dialysis, we could enrich for the largest class of particles (∼4–5 nm) (Figure 2D), indicating that the most slowly migrating band corresponds to an aggregate.

To verify that the gel-shifted Cse4 band is the same species that was measured by AFM, we stained the same native polyacrylamide gel successively with ethidium bromide to visualize the DNA and with Coomassie blue to visualize the histones. We found that the single major gel-shifted particle obtained by assembly of Cse4 with α62 DNA is also the single major histone-containing species (Supplementary Figure S4). We also determined the histone composition of the gel-shifted H3 and Cse4 particles by excising the gel bands and running SDS–PAGE. We found that all four histones are present in equimolar amounts for both major H3 bands and for the single major Cse4 band (Figure 2E and F). We conclude that the single major Cse4 species measured by AFM to be the height of a tetrameric particle is the major Cse4 gel-shifted species and contains all four histones that were present in the assembly reaction.

Ferguson plot analysis confirms the sizes of gel-shifted bands

We also estimated particle sizes directly from gel shifts, by observing changes in migration as a function of polyacrylamide concentration. As both charge and size affect the migration of particles in native gels, the migratory position of DNA/histone complexes at a single gel concentration cannot be used to infer their relative sizes (Figure 3A). This limitation is overcome by electrophoresing the same samples on multiple gels with varying polyacrylamide concentration, then plotting migration versus gel concentration (Figure 3B) to estimate particle sizes (Ferguson plot analysis). DNA standards were used to calibrate gel parameters. By applying curve fitting, the geometric mean radius was calculated for each histone–DNA complex on the gel (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Ferguson plot analysis of gel-shifted bands. (A) Example of a 7% native gel used for Ferguson plot analysis of gel-shifted species. Calculated particle radii bands are boxed: hemisomes (red), octasomes (blue) and aggregates (green). Asterisks indicate an unidentified α62-derived species that lacks protein based on SDS–PAGE analysis (data not shown). (B) Example of a Ferguson analysis for a Cse4-Δ90/α62 particle (red), where black lines indicate DNA standard mobilities for the corresponding 5–10% series. (C) Calculated dimensions based on three independent experiments, along with observed and expected hemisome:octasome ratios (see text). We compared the distribution of measurements between hemisomes and octasomes by t-test, and the P-value was determined to be 0.0003 for both H3 and Cse4-Δ90.

For particle size estimation, we assembled particles using either 62 or 147-bp fragments. Histone octamers contained either H3 or Cse4-Δ90, which is N-terminally deleted for 90 aa and is similar in MW to H3. Ferguson plot analysis of histone–DNA complexes on 62-bp fragments yielded 3.38 ± 0.07 nm for H3 and 3.48 ± 0.17 for Cse4-Δ90 (red boxes in Figure 3A). Similar calculations for 147-bp fragments yielded 3.68 ± 0.11 for H3 and 3.79 ± 0.09 nm for Cse4-Δ90 (blue boxes in Figure 3A). A two-tailed t-test between hemisomes and octasomes for both H3 and Cse4 yielded P-values of 0.0003 for both; therefore, the observed differences in Ferguson plot measurements for hemisomes and octasomes are robust. Calculations for the more slowly migrating bands (green boxes in Figure 3A) indicated mean radii of >5 nm, far exceeding the expected value for octasome-sized particles, which implies that the ∼4–5 nm particles observed by AFM (Figure 2C and D) consist of aggregates larger than pseudo-octasomes.

We then asked whether the differences between mean radii measured for hemisomes and octasomes are consistent with their expected dimensions. An octameric nucleosome can be modeled as a cylinder with a radius (r) of 5 nm and a height (h) of 6 nm, and a hemisome should be half this height. The migration of a particle in the gel is proportional to its cross-sectional diagonal, d = sqrt[(2 r)2 + h2], assuming that the long histone tails collapse uniformly around the core. Therefore, the expected mean radius ratio between a hemisome and an octasome is ∼90%. The 601-147 sequence had been chosen for efficient assembly of H3 and Cse4 octameric nucleosomes (17,19) and served as the DNA for known octasome controls. For both H3 and Cse4, we measured the mean radius ratio between particles wrapped by 62-bp sequences and those wrapped by 147-bp sequences to be 92%, consistent with these latter particles being hemisomes. Thus, Ferguson plot analysis supports our conclusions based on AFM height measurements that pseudo-octasomes split into hemisomes when dialyzed versus low salt.

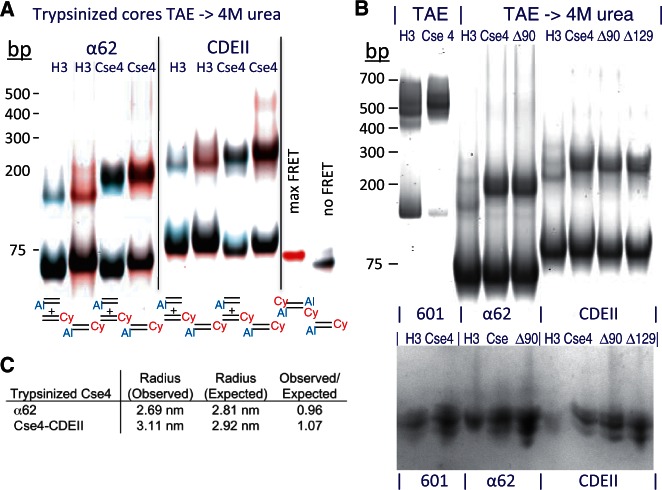

A gelFRET assay directly confirms hemisome formation

To obtain direct confirmation that the particles we have characterized based on physical properties correspond to well-wrapped hemisomes, we took advantage of the fact that when a 62-bp DNA duplex wraps around a hemisome the two ends approach one another within ∼60 Å (Figure 4A), which is close enough for a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) signal to be detected using appropriate fluorophores, such as Alexa 488 and Cy3 [R0 = 67.5 Å (32)]. In contrast, the distance between ends of unwrapped duplexes is ∼200 Å. Given that FRET intensity falls off as the sixth power of the radius, even partial unwrapping is expected to drastically diminish the FRET emission, making FRET a powerful qualitative method for determining whether a DNA duplex wraps tightly around a histone core particle. FRET can be observed directly in electrophoretic gels (‘gelFRET’), where it has been used to make qualitative distinctions between gel-shifted particles (33).

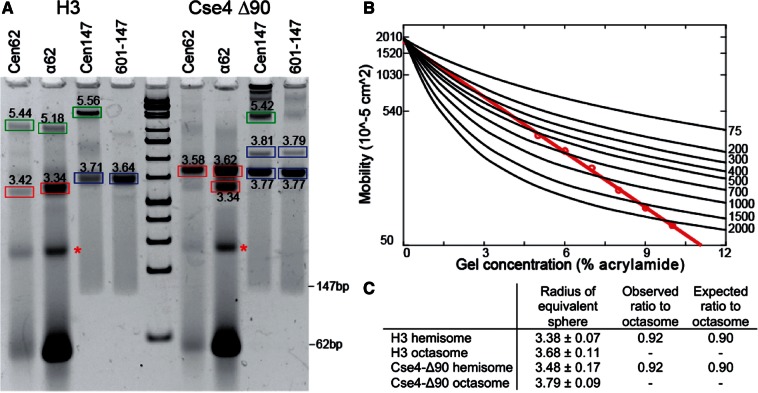

Figure 4.

A gelFRET assay directly confirms hemisome formation. (A) Structural model based on PDB 1KX5, showing that a 62-bp duplex is sufficient to wrap a hemisome. (B) FRET strategy using Alexa488 as donor and Cy3 as acceptor, where colors illustrate wavelength and curves represent approximate spectral overlap. (C) GelFRET analysis of a representative gel-shift experiment in which H3 or Cse4 octamers and mixed singly or doubly end-labeled duplexes (as indicated below each lane with 5′ Cy3 on α62 R and 3′ Alexa488 on α62 F) were combined in 2 M NaCl, subjected to dialysis versus 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) + 0.25 mM EDTA and electrophoresed on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel, followed by scanning for gelFRET. A doubly end-labeled DNA band showing no FRET signal served as a negative control. Al = Alexa 488. Cy = Cy3 (D) Deletion of the Cse4 N-terminal tail increases gel-shift mobility. Octamers containing tail-deleted Cse4 were assembled with α62 DNA duplexes labeled for gelFRET. DNA standards are included only as a rough guide. (E) As a negative control, H2A/H2B dimers were used for assembly (Supplementary Figure S5). When DNA fragments are in large molar excess, single H2A/H2B dimers bind and cause a gel shift (34). Rapidly migrating dye-coupled fragments resolve from one another with Alexa488 (which is coupled via an amino-C7 linker) causing slower migration than Cy3 (which is directly coupled) of otherwise identical fragments, and resulting in misalignment of mixed Cy3 and Alexa488 fragments. (F) Quantification of gelFRET emissions for the bands shown in the figure.

Alexa 488 served as the donor fluorophore attached to one end of the duplex and Cy3 as acceptor fluorophore attached to the other end. Two different fluorophore configurations were used, one in which Alexa 488 and Cy3 were at opposite ends of the same duplex, and one in which each duplex had either Alexa 488 or Cy3, but not both, and equal mixtures of these singly labeled fluorophores were mixed together. To observe the FRET signal for each band in the gel, we scanned the gel with a 488-nm laser to excite Alexa 488, and measured FRET at 670 nm and then excited at 488 nm in a second scan and measured donor emission at 526 nm (Figure 4B). By balancing and superimposing the two scanned images, we could visualize the FRET-versus-donor emission signals throughout the gel. The channels were balanced such that the background would be white and a band lacking FRET would be gray, and with increasing FRET, a band would become increasingly red. We observed striking differences between matched samples containing duplexes with both fluorophores and with a mixture of duplexes containing single fluorophores (Figure 4C). Samples with a mixture of single fluorophores showed gray bands for both the H3 and Cse4 hemisomes, and both showed a conspicuously reddish band when the fluorophores were at opposite ends of the same duplex. For the slower migrating H3 aggregate, the mixture of singly labeled duplexes showed a brownish band, whereas the doubly labeled duplex showed a scarlet signal. FRET signals in gel-shifted aggregates are expected when there are two or more DNA duplexes with oppositely labeled ends that can interact within the aggregate.

The larger H3 product migrated at ∼1.5 kb on 6% native PAGE gels, whereas the smaller product migrated at 550 bp. We attribute these differences in migration between H3 and Cse4 particles to the fact that the Cse4 N-terminal tail is ∼90 aa longer than the H3 tail, which suggests an equivalence between the Cse4 680-bp band and the H3 550-bp band. Consistent with this interpretation, we found that gel-shifted particles assembled using Cse4-Δ129 migrated faster than particles assembled using full-length Cse4 (Figure 4D). When we excised gel-shifted bands and subjected them to SDS–PAGE gel analyses, we determined that the 550-bp and ∼1.5-kb H3 bands and the 680-bp Cse4 band contained all four histones present in the assembly reaction (Figure 2E and F).

To quantify the FRET signal, we measured donor and FRET emissions at the peak density of each band. For no-FRET controls, we measured the donor emission and FRET signals from bands in the gel that had not undergone a gel shift, either run in a nearby lane or in the same lane. To estimate the maximum possible FRET signal, we used a duplex in which both fluorophores were at both ends of the duplex. These measurements show that there is little if any FRET signal emitted from the hemisome bands of mixed single fluorophores, but that there is a 10–15% FRET signal emitted from bands with the two fluorophores on opposite ends, consistent with tight wrapping of a single DNA duplex around the histone core (Figure 4E). Similarly, a dramatic difference was seen for the H3 aggregate bands, where the band with a mixture of singly labeled fluorophores showed ∼5% emission, whereas the band with doubly labeled fluorophores showed 25–30% emission. These measurements confirm that the aggregate particle contains at least two tightly wrapped DNA duplexes because some FRET is expected whenever oppositely labeled ends of two duplexes are near to one another, whereas much stronger FRET is expected when both ends are oppositely labeled.

To verify that protein association in the absence of nucleosome-like wrapping of DNA does not result in a FRET signal, we used histone H2A/H2B dimers as control. When in large DNA excess, single H2A/H2B dimers are known to stably associate with DNA in an extended conformation (34). As expected, association of H2A/H2B with DNA resulted in gel-shifted bands; however, we did not detect significant FRET signals (Figure 4E and F), despite detection of strong FRET signals for H3 and Cse4-Δ90 hemisomes assembled in parallel (Supplementary Figure S5).

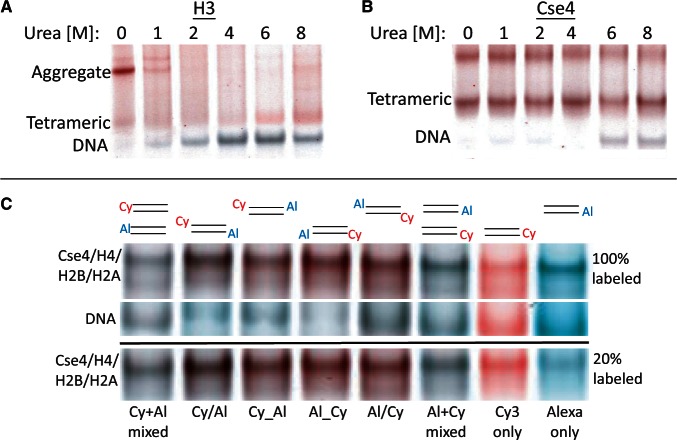

Cse4 hemisomes are stable in high concentrations of urea

Hemisomes remain stable after storage at 4°C for at least several days (see Supplementary Figure S6). To systematically assess particle stability without interfering with electrostatic interactions, we dialyzed against urea, a widely used protein denaturant. When assembly reactions containing H3 and Cse4 particles and α62 DNA in 2 M NaCl were dialyzed directly into a 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) + 0.25 mM EDTA buffer with no additional salt, but increasing concentrations of urea at 4°C, H3 aggregates disappeared between 1 and 2 M urea, accompanied by the appearance of unwrapped DNA that showed no FRET signal (Figure 5A). Surprisingly, the same treatment had no effect on Cse4 hemisomes up to 4 M urea, and most hemisomes remained intact up to 8 M urea, showing strong FRET signals (Figure 5B). Dialysis into 4 M urea resulted in stable hemisomes with FRET signals using all four possible combinations of fluorophores on both ends of the 62-bp DNA duplex, and no difference was seen when assembly was performed in a 4-fold excess of unlabeled fragment (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Cse4 hemisomes are stable in high concentrations of urea. (A and B) Native 6% gelFRET showing gel-shifted particles after dialysis versus 10 mM HEPES (pH7.5) + 0.25 mM EDTA containing the indicated concentrations of urea, using H3 octamers (A) and Cse4 octamers (B). The slowly migrating Cse4 band varies between experiments (see Supplementary Figure S7) and might represent an intact pseudo-octasome, a ‘stack’ of hemisomes or a stable aggregate. (C) Cse4 octamers and α62 duplexes were dialyzed versus 4 M urea + 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) + 0.25 mM EDTA using different combinations of end-labeled fluorophores as indicated, where Cy or Al on left indicates a 5′ label on α62 F oligonucleotide, and on right for α62 R. For each lane, a DNA band corresponding to the band marked by asterisks in Figure 3A is shown in the middle image and served as a negative control. The lower image shows gel shifts for labeled α62 duplexes that had been diluted 5-fold with unlabeled α62 duplexes.

To exclude the possibility that the fluorophores themselves inhibit pseudo-octasome formation, we also performed FRET gel-shift assays using 5-fold dilutions of labeled fluorophores with otherwise identical unlabeled duplexes. We observed similar FRET signal differences between singly and doubly labeled duplexes when diluted with unlabeled DNA, as we observed using pure labeled duplexes (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure S7).

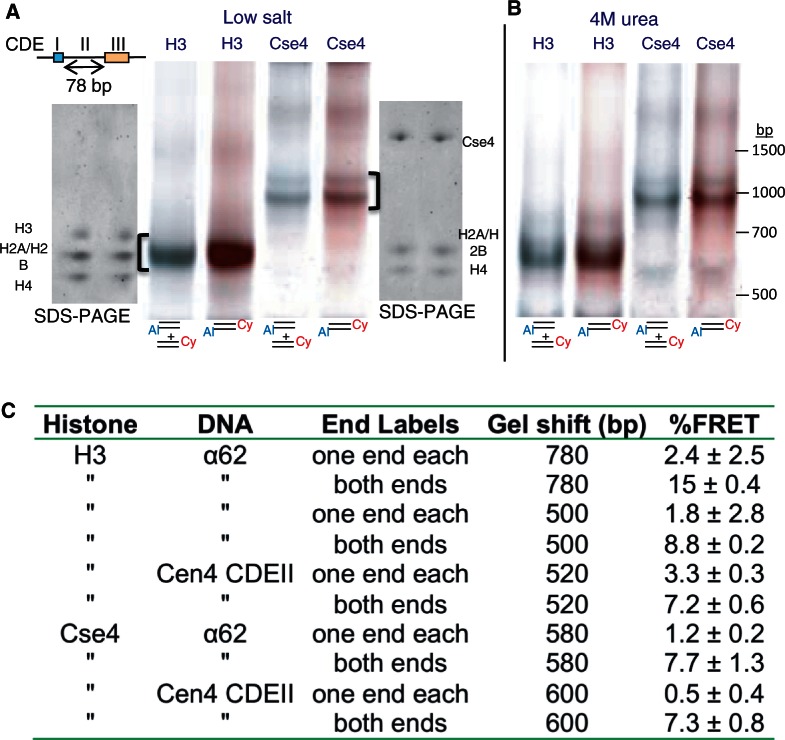

Stable Cse4 and H3 hemisomes form on CDEII DNA

We next asked whether the protocol that we used for assembling H3 and Cse4 hemisomes with α62 DNA would suffice for assembling hemisomes using a complete CDEII DNA duplex. We chose the CDEII from Chromosome 4, which at 78 bp is the shortest CDEII sequence in the yeast genome. Our previous in vivo mapping of Cse4 showed that the Cen4 CDEII is especially well delineated using ChIP (13), and others have used Cen4 in their studies of Cse4 nucleosomes (7,11). Using our gelFRET assay, we found that both H3 and Cse4 particles form on Cen4 CDEII and migrate as expected for tetramers (Figure 6A), and particle size distributions were confirmed by AFM analysis (see Supplementary Figure S8). We also observed hemisome formation on a 62-bp fragment derived from Cen3 CDEII based on Ferguson plot analysis (Figure 2E and F). Whether assembled using H3 or Cse4, Cen4 CDEII particles were stable when dialyzed directly into 4 M urea (Figure 6B). We conclude that CDEII is a suitable substrate for hemisome assembly.

Figure 6.

Stable Cse4 and H3 hemisomes form over CDEII DNA. (A) Both H3 and Cse4 split into hemisomes with 78-bp Cen4 CDEII DNA duplexes after dialysis versus 0.25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and native 6% PAGE. Loading and electrophoresis of gel slices excised from these gels (brackets) onto SDS–PAGE gels confirms that all four histones were present in the gel-shifted particles. (B) Same as (A) except that dialysis was versus 4 M urea + 0.25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). (C) Assembly mixtures containing a 4:1 ratio of unlabeled:labeled duplex in 2 M NaCl were dialyzed versus low salt and electrophoresed. %FRET values from four experiments were calculated as in Figure 5E. The free DNA band in each lane served as a no-FRET standard (see Supplementary Figure S6), and a doubly labeled duplex with both fluorophores at each end run in a separate lane served as a 100% standard. Mean and standard deviations for three experiments are shown.

Quantification of FRET-versus-donor signals for α62 and Cen4 CDEII from multiple experiments differing only in the composition of low-salt buffer used for dialysis confirmed the consistent presence of a moderate-to-strong FRET signal from the doubly labeled hemisomes and aggregates, the consistent presence of a weak FRET signal from the singly labeled aggregates and the lack of a significant FRET signal from the singly labeled hemisomes (Figure 6C). We conclude that there is a single DNA duplex that wraps tightly around the hemisome.

Hemisomes form on tailless histone cores

There are two notable differences between particles produced using CDEII DNA compared with those using α62 DNA. First, no distinct CDEII aggregates were evident (Figure 6A and B), suggesting that some sequence feature of CDEII DNA inhibits aggregation. Second, H3 hemisomes were highly homogeneous, whereas Cse4 hemisomes on the 78-bp Cen4 CDEII, typically gel shifted as a pair of closely spaced particles. We suspected that this difference resulted from binding of the long highly arginine-rich Cse4 N-terminal tail to the 16 bp of excess DNA that would be protruding from the 78-bp CDEII DNA duplex. To test this possibility, we subjected both H3 and Cse4 octamers to trypsin treatment in 2 M NaCl before assembly, using conditions that removed all histone tails (see Supplementary Figure S9). Trypsinized cores were mixed with DNA duplexes and subjected to successive dialyses versus low-salt and 4 M urea. For both H3 and Cse4, we observed a moderate gel shift to the same degree (Figure 7A). Similar results were obtained using Cse4-Δ90 and Cse4-Δ129 pre-treated with trypsin (Figure 7B). Importantly, gel-shifted bands displayed significant FRET signals when doubly labeled DNA duplexes were used and insignificant FRET signals for mixed singly labeled duplexes, confirming that these gel-shifted bands represent hemisomes that are stable in 4 M urea. Additional confirmation was obtained by Ferguson plot analysis, which showed that the dimensions of tailless Cse4 particles are close to those expected for hemisomes (Figure 7C). We also noted that tailless Cse4 hemisomes remained mostly intact after dialysis into 4 M urea, whereas tailless H3 hemisomes showed partial depletion relative to free DNA (Supplementary Figure S10). The production of stable hemisomes using trypsinized H3 and Cse4 cores demonstrates that hemisomes can be produced by splitting of octamer cores even in the absence of histone tails. We attribute the remarkable stability of α62- and CDEII-assembled Cse4 hemisome cores to protection of the entire perimeter by DNA wrapping, thus excluding urea to maintain the particle intact.

Figure 7.

Hemisomes form on tailless histone cores. (A) Gel-shifts and gelFRET of particles were assembled in TAE (Supplementary Figure S10), then transferred to 4 M urea using trypsinized H3 or Cse4 cores and α62 or Cen4 CDEII duplexes labeled as indicated, together with maximum-FRET and no-FRET controls. (B) Gel-shifts of trypsinized cores from H3, Cse4, Cse4-Δ90 (Δ90) and Cse4-Δ129 (Δ129) mixed with unlabeled duplexes of 601-145, α62 and Cen4 CDEII duplexes. Top panel: Ethidium bromide-stained gel. Bottom panel: Gel-shifted bands were excised, loaded onto an 18% SDS–PAGE gel in the same order, electrophoresed and silver stained. DNA standards are included only as a rough guide. (C) Ferguson plot analysis of trypsinized Cse4/α62 and Cse4/CDEII shows close correspondences between observed and expected radii of equivalent spheres, where the radius refers to the radius of the geometric mean. Unfortunately, assembly reactions with trypsinized cores and 147-bp DNA resulted in aggregation (data not shown). Averages are shown for samples dialyzed versus low-salt and low-salt followed by 4 M urea, which were similar. AFM was not performed on trypsinized particles because histone tails are required to immobilize nucleosomes on the mica surface (28).

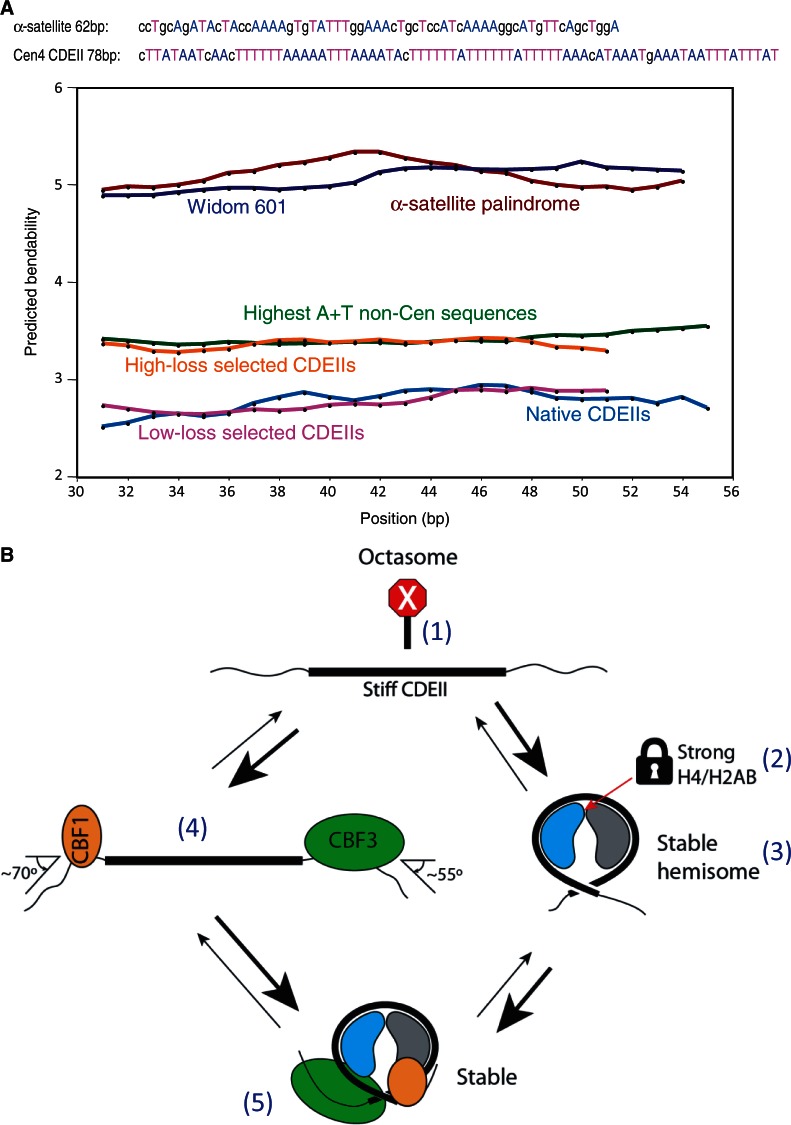

CDEII DNA is exceptionally stiff

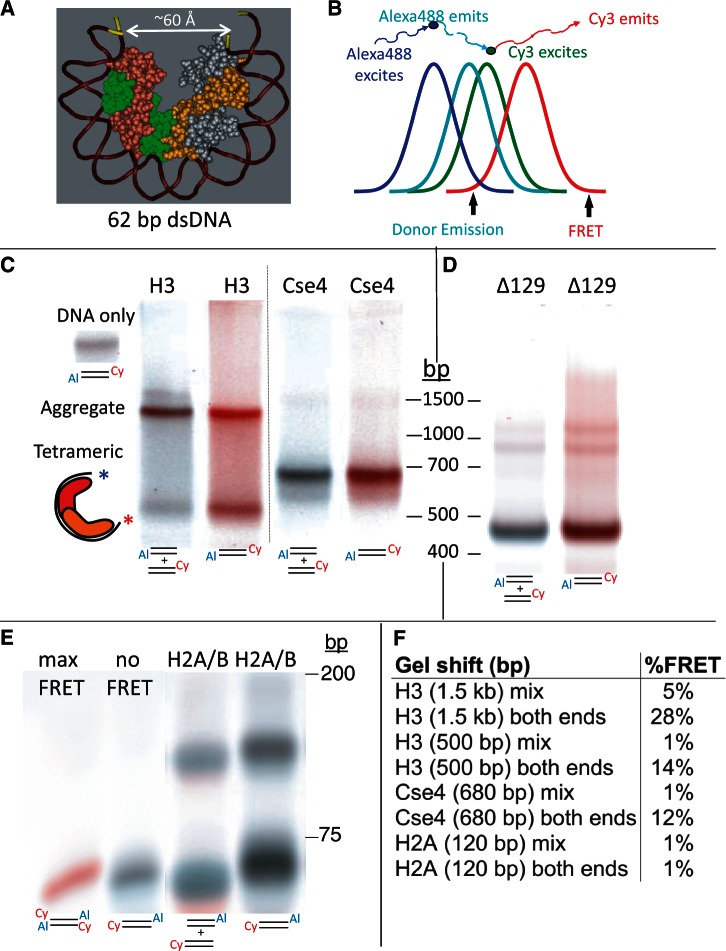

We wondered why CDEII DNA readily forms hemisomes with either H3 or Cse4, but in general is a poor substrate for H3 and Cse4 octasome assembly (6). The sequence composition of CDEII of all 16 yeast chromosomes is ∼90% A + T, and the Cen4 CDEII is typical (92% A + T). In addition, CDEII is significantly enriched in runs of As and Ts (35). Previously, Baker and Rogers used a plasmid loss assay to select for CDEII variants that differed in centromere stability (35). By randomizing a 79-bp CDEII sequence and holding the base composition constant, they constructed a yeast minichromosome transformation library in which these random CDEII sequences were inserted in between CDEI and CDEIII. Using a color marker and observing colony sectoring, they selected for strains in which the degree of plasmid loss was either much higher than normal (high-loss strains) or indistinguishable from normal (low-loss strains). Remarkably, the low-loss strains showed a significant excess of runs of As and Ts, whereas the high-loss strains appeared to be no different from random.

Poly (dA)•(dT) tracts narrow the DNA minor groove, which becomes occupied by a ‘spine’ of structured water that stiffens the double helix (36) and causes local bending (37). To determine whether CDEII sequences are especially stiff, we asked whether the computationally predicted bendability of CDEII sequences is lower than what would be expected for sequences of similar AT richness (38). We compared the predicted bendabilities of all 16 CDEII sequences to those of the 24 sequences within the yeast genome that are at least 88% A + T over a span of at least 100 bp. We found that on average, the CDEII sequences are predicted to be stiffer than these 24 non-centromeric sequences (Figure 8A). Moreover, the Baker-Rogers low-loss sequences are predicted to be as stiff as native CDEIIs, whereas the high-loss sequences are predicted to be as bendable as the 24 non-centromeric sequences. In contrast, the inverted repeat α-satellite and Widom 601 sequences that have been used to assemble cenH3 octasomes are predicted to be far more flexible than either class of AT-rich sequences (Figure 8A). This difference in predicted bendability between sequences that readily form octasomes and CDEII sequences that disfavor octasome assembly suggests that CDEII has evolved to resist octasome formation.

Figure 8.

CDEII DNA is exceptionally stiff. (A) Bendability predictions for DNA segments using the Bend-it server (http://hydra.icgeb.trieste.it/dna/bend_it.html) (38). Predictions for the 147-bp α-satellite palindrome (brown) and Widom 601 (dark blue) duplexes used in this and previous studies for assembling cenH3 octasomes show that these sequences are predicted to be bendable relative to the 24 most AT-rich non-centromeric (green) and high-loss selected centromeric sequences (orange). The latter sequences are predicted to be more bendable than native CDEII (light blue) and low-loss selected CDEII (magenta) sequences. Sequences used to split octamers in this study are shown with As and Ts highlighted to illustrate that CDEIIs are especially rich in runs of As and Ts. Default parameters were used, except that the window size was lengthened for 147-bp sequences to compensate for their much longer lengths and to simplify the display, although similar averages were obtained using the default window size of 31 bp. (B) Five factors contribute to stable occupancy of Cse4 hemisomes at CDEII: (1) The extreme stiffness of CDEII DNA (thick line) makes wrapping more than once around an octasome difficult relative to the incomplete wrapping around a horseshoe-shaped hemisome. As a result, hemisomes are stable on CDEII DNA, but octasomes are not. (2) The H4/H2B junction at the center of the Cse4 hemisome is strong, unlike the H4/H2B junction in H3 nucleosomes, which is weak relative to the H3/H3 junction and therefore causes octamers to dissociate into an (H3/H4)2 tetramer and two H2A/H2B dimers. (3) The Cse4 hemisome is stable even in the absence of Cbf1 and CBF3. (4) Cbf1 and CBF3 bind avidly to and sharply bend the DNA immediately flanking CDEII and so expose only ∼80 bp of DNA, which can accommodate heterotypic tetramers, but not octamers. (5) Although highly stable H3 hemisomes can form on CDEII in vitro, they are strongly disfavored in vivo because the CBF3 complex is known to specifically recruit Cse4, which would displace H3-containing nucleosomes. Cse4/H4 heterodimers are depicted in blue and H2A/H2B in gray.

DISCUSSION

We have used a variety of in vitro reconstitution and assay methods to determine the physical basis for differences between cenH3 nucleosomes at centromeres and H3 nucleosomes on chromosome arms. We find that the junction between H4 and H2B at the center of the hemisome that preferentially dissociates in H3 octamers is stable in Cse4 octamers, and that stable hemisomes can be readily produced using a non-traditional reconstitution method (25). We have been able to reconstitute hemisomes that are identical in sequence and composition to those mapped to a yeast centromere (13). This precise correspondence between the products of in vivo and in vitro assembly addresses a controversy that has been fueled by the lack of direct evidence for any centromere-specific particle other than hemisomes in vivo, and by the inability of several groups to reconstitute hemisomes in vitro. Our demonstration that hemisomes assembled on both α-satellite and CDEII sequences are stable in 4 M urea belies the assertion that hemisomes must be unstable intermediates in the assembly of more conventional cenH3 octamers (1,22).

Previous difficulties in assembling Cse4 nucleosomes over yeast centromeric DNA segments have led to the expectation that non-histone proteins would be required (6,17). Both Cbf1 and the CBF3 complex sharply bend DNA, and the Ndc10 protein has been proposed to interact with both sides of the CDE loop, leading to models in which these DNA-binding proteins act to hold the CDEII loop together and stabilize the Cse4 nucleosome (6,39,40). In addition, it has been claimed that the Scm3 chaperone binds AT-rich DNA and facilitates the stable assembly of a Cse4 tetramer (6). Our findings directly demonstrate that these non-histone proteins are not necessary for stable assembly of the Cse4 hemisome at CDEII, and provide the basis for an alternative explanation for the role of these proteins in organizing the kinetochore (Figure 8B). The exceptional stiffness of CDEII makes it inherently resistant to octasome formation, and it seems likely that stiffness also contributes to the maintenance of right-handed Cse4 nucleosomes at the highly AT-rich yeast two-micron STB sequence (41). Resistance to octasome formation would be augumented by the tight binding and DNA bending of CDEI by Cbf1 and CDEIII by the CBF3 complex on either side of CDEII, allowing only hemisomes to assemble. By recruiting Cse4, the CBF3/Ndc10 complex also maintains high Cse4 hemisome occupancy at CDEII (42,43), thus excluding H3 hemisomes, which we have shown can also stably assemble with CDEII DNA. Although Cbf1 and CBF3 might help to hold together both sides of the CDEII loop, the fact that hemisomes appear to be stable in animal centromeres without homologs of these DNA-binding proteins suggests that any such stabilization is more likely to be a secondary consequence of their primary role in maintaining high occupancy of hemisomes and excluding octasome formation.

The minimum requirement for a functional yeast centromere is CDEIII with an adjacent AT-rich region (44), and our study provides a simple model for why AT-richness is required to maintain centromeres. AT-rich regions exclude octasomes (45), but as we show, they are nevertheless compatible with hemisome formation. We suggest that any DNA sequence that is sufficiently AT-rich will be stiff enough to exclude octasomes because flexibility is needed to make a second turn around the octameric histone core. Stiff DNA can nevertheless make a single wrap around a horseshoe-shaped hemisome core. As DNA stiffness increases with increasing A + T content and runs of As and Ts, making more than a single wrap around an octameric core becomes increasingly difficult, thus further favoring hemisomes over octasomes. At yeast centromeres, the need to exclude H3 octamers is strongly selected for because even loss of a single centromeric nucleosome is a lethal event. Baker and Rogers used an exquisitely sensitive assay to select for low-loss and high-loss centromeres that differ in segregation fidelity over a 100-fold range (35), but even high-loss centromeres lose chromosomes at such a low rate that the loss of fitness would be imperceptible in standard growth assays. However, over long evolutionary periods, the need to exclude octamers will result in CDEII sequences evolving toward becoming the stiffest DNA sequences in the yeast genome. Cse4 hemisomes will be preferentially incorporated at CDEII both because Cse4 is recruited by the CBF3 complex at CDEIII and because the H4/H2B junction at the center of the hemisome is less prone to dissociate in Cse4 than in H3 nucleosomes.

Although budding yeast are exceptional in having genetically defined point centromeres, our findings have implications for epigenetic centromeres. The fact that yeast Cse4 can substitute for human CENP-A (15), and the ease with which we can produce stable hemisomes in vitro on completely unrelated sequences, suggests that hemisomes can form spontaneously wherever octasomes are excluded. It is unlikely that satellite sequences have evolved to exclude octasomes, but we think that this is because they play a dual role in chromosome segregation: Satellite sequences harbor alternating arrays of both cenH3 hemisomes that organize the kinetochore and flanking heterochromatic H3 octasomes that are needed for alignment and cohesion of sister chromatids on the metaphase plate. We do not know whether there are DNA-binding proteins that play the same role in organizing the kinetochore as Cbf1 and the CBF3 complex in yeast. However, recent studies have identified complexes that might serve to exclude octamers and thus favor hemisome formation, such as the CENP-S/T/W/X complex, which is a heterotypic tetramer that is thought to wrap centromeric DNA in a horseshoe-shaped structure during mitosis (46). In this way, the evolution of genetically defined point centromeres from ancestral epigenetic regional centromeres might be seen as an elaboration of an ancient mechanism for perpetual retention of cenH3 hemisomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figures 1–10, Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary References [47–49].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Yamini Dalal for pointing out the previously overlooked Tatchell and van Holde article, John Sumida of the University of Washington Biopharmacy Core Facility for analytical sedimentation analyses, Dietmar Tietz for Ferguson plot analysis software and advice, Terry Bryson and Aaron Hernandez for aiding with plasmid constructs and bacterial cultures, Martin Singleton and Karolin Luger for plasmids and Paul Talbert and Srinivas Ramachandran for comments on the manuscript.

FUNDING

Howard Hughes Medical Institute; National Institutes of Health [U54 CA143862]. Funding for open access charge: Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black BE, Cleveland DW. Epigenetic centromere propagation and the nature of CENP-A nucleosomes. Cell. 2011;144:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henikoff S, Furuyama T. The unconventional structure of centromeric nucleosomes. Chromosoma. 2012;121:341–352. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0372-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik HS, Henikoff S. Major evolutionary transitions in centromere complexity. Cell. 2009;138:1067–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camahort R, Shivaraju M, Mattingly M, Li B, Nakanishi S, Zhu D, Shilatifard A, Workman JL, Gerton JL. Cse4 is part of an octameric nucleosome in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:794–805. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalal Y, Furuyama T, Vermaak D, Henikoff S. Structure, dynamics, and evolution of centromeric nucleosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15974–15981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707648104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao H, Mizuguchi G, Wisniewski J, Huang Y, Wei D, Wu C. Nonhistone Scm3 binds to AT-rich DNA to organize atypical centromeric nucleosome of budding yeast. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lochmann B, Ivanov D. Histone h3 localizes to the centromeric DNA in budding yeast. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal Y, Wang H, Lindsay S, Henikoff S. Tetrameric structure of centromeric nucleosomes in interphase Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitriadis EK, Weber C, Gill RK, Diekmann S, Dalal Y. Tetrameric organization of vertebrate centromeric nucleosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20317–20322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009563107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bui M, Dimitriadis EK, Hoischen C, An E, Quenet D, Giebe S, Nita-Lazar A, Diekmann S, Dalal Y. Cell-cycle-dependent structural transitions in the human CENP-A nucleosome in vivo. Cell. 2012;150:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuyama S, Biggins S. Centromere identity is specified by a single centromeric nucleosome in budding yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14706–14711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706985104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuyama T, Henikoff S. Centromeric nucleosomes induce positive DNA supercoils. Cell. 2009;138:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krassovsky K, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Tripartite organization of centromeric chromatin in budding yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:243–248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118898109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shivaraju M, Unruh JR, Slaughter BD, Mattingly M, Berman J, Gerton JL. Cell-cycle-coupled structural oscillation of centromeric nucleosomes in yeast. Cell. 2012;150:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieland G, Orthaus S, Ohndorf S, Diekmann S, Hemmerich P. Functional complementation of human centromere protein A (CENP-A) by Cse4p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:6620–6630. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6620-6630.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tachiwana H, Kagawa W, Shiga T, Osakabe A, Miya Y, Saito K, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Oda T, Sato M, Park SY, et al. Crystal structure of the human centromeric nucleosome containing CENP-A. Nature. 2011;476:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dechassa ML, Wyns K, Li M, Hall MA, Wang MD, Luger K. Structure and Scm3-mediated assembly of budding yeast centromeric nucleosomes. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:313. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuguchi G, Xiao H, Wisniewski J, Smith MM, Wu C. Nonhistone Scm3 and histones CenH3-H4 assemble the core of centromere-specific nucleosomes. Cell. 2007;129: 1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kingston IJ, Yung JS, Singleton MR. Biophysical characterization of the centromere-specific nucleosome from budding yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:4021–4026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conde e Silva N, Black BE, Sivolob A, Filipski J, Cleveland DW, Prunell A. CENP-A-containing nucleosomes: easier disassembly versus exclusive centromeric localization. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:555–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoda K, Ando S, Morishita S, Houmura K, Hashimoto K, Takeyasu K, Okazaki T. Human centromere protein A (CENP-A) can replace histone 3 in nucleosome reconstitution in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7266–7271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130189697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekulic N, Bassett EA, Rogers DJ, Black BE. The structure of (CENP-A-H4)(2) reveals physical features that mark centromeres. Nature. 2010;467:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature09323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Colmenares SU, Karpen GH. Assembly of Drosophila centromeric nucleosomes requires CID dimerization. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatchell K, Van Holde KE. Nucleosome reconstitution: effect of DNA length on nuclesome structure. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2871–2880. doi: 10.1021/bi00580a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Hayes JJ. Large scale preparation of nucleosomes containing site-specifically chemically modified histones lacking the core histone tail domains. Methods. 2004;33:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Bash R, Yodh JG, Hager GL, Lohr D, Lindsay SM. Glutaraldehyde modified mica: a new surface for atomic force microscopy of chromatin. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3619–3625. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75362-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eickbush TH, Moudrianakis EN. The histone core complex: an octamer assembled by two sets of protein-protein interactions. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4955–4964. doi: 10.1021/bi00616a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomschik M, Karymov MA, Zlatanova J, Leuba SH. The archaeal histone-fold protein HMf organizes DNA into bona fide chromatin fibers. Structure. 2001;9:1201–1211. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallrabe H, Stanley M, Periasamy A, Barroso M. One- and two-photon fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy to establish a clustered distribution of receptor-ligand complexes in endocytic membranes. J. Biomed. Opt. 2003;8:339–346. doi: 10.1117/1.1584444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez-Carrozzi V, Kerppola T. Gel-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer (gelFRET) analysis of nucleoprotein complex architecture. Methods. 2001;25:31–43. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aragay AM, Diaz P, Daban JR. Association of nucleosome core particle DNA with different histone oligomers. Transfer of histones between DNA-(H2A,H2B) and DNA-(H3,H4) complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;204:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker RE, Rogers K. Genetic and genomic analysis of the AT-rich centromere DNA element II of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;171:1463–1475. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods KK, Maehigashi T, Howerton SB, Sines CC, Tannenbaum S, Williams LD. High-resolution structure of an extended A-tract: [d(CGCAAATTTGCG)]2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15330–15331. doi: 10.1021/ja045207x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson JN. Detection, sequence patterns and function of unusual DNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8513–8533. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlahovicek K, Kajan L, Pongor S. DNA analysis servers: plot.it, bend.it, model.it and IS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3686–3687. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho US, Harrison SC. Recognition of the centromere-specific histone Cse4 by the chaperone Scm3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9367–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106389108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hemmerich P, Stoyan T, Wieland G, Koch M, Lechner J, Diekmann S. Interaction of yeast kinetochore proteins with centromere-protein/transcription factor Cbf1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12583–12588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang CC, Chang KM, Cui H, Jayaram M. Histone H3-variant Cse4-induced positive DNA supercoiling in the yeast plasmid has implications for a plasmid origin of a chromosome centromere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:13671–13676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101944108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho US, Harrison SC. Ndc10 is a platform for inner kinetochore assembly in budding yeast. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz J, Stemmann O, Rank S, Lechner J. A putative protein complex consisting of Ctf19, Mcm21, and Okp1 represents a missing link in the budding yeast kinetochore. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1140–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sears DD, Hegemann JH, Shero JH, Hieter P. Cis-acting determinants affecting centromere function, sister-chromatid cohesion and reciprocal recombination during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;139:1159–1173. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iyer V, Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 1995;14:2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishino T, Takeuchi K, Gascoigne KE, Suzuki A, Hori T, Oyama T, Morikawa K, Cheeseman IM, Fukagawa T. CENP-T-W-S-X forms a unique centromeric chromatin structure with a histone-like fold. Cell. 2012;148:487–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyer PN, Edayathumangalam RS, White CL, Bao Y, Chakravarthy S, Muthurajan UM, Luger K. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akaishi T, Yokosawa H, Sawada H. Regulatory subunit complex dissociated from 26S proteasome: isolation and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1245:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tietz D. Analysis of one-dimensional gels and two-dimensional Serwer-type gels on the basis of the extended Ogston model using personal computers. Electrophoresis. 1991;12:28–39. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150120107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.