Background: Thioethers have been observed in therapeutic antibodies, with increasing levels upon storage.

Results: IgG1 thioether bond formation is naturally occurring, but the formation rate depends on light chain type.

Conclusion: Slower thioether bond formation on IgG1κ is caused by dehydrogenation impairment through its light chain.

Significance: Safety concerns associated with thioether control on therapeutic antibodies are diminished by its natural production.

Keywords: Antibodies, Disulfide, Drug Development, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Post Translational Modification, Light Chain

Abstract

During either production or storage, the LC214-HC220 disulfide in therapeutic antibodies can convert to a thioether bond. Here we report that a thioether forms at the same position on antibodies in vivo. An IgG1κ therapeutic antibody dosed in humans formed a thioether at this position at a rate of about 0.1%/day while circulating in blood. Thioether modifications were also found at this position in endogenous antibodies isolated from healthy human subjects, at levels consistent with this conversion rate. For both endogenous antibodies and recombinant antibodies studied in vivo, thioether conversion rates were faster for IgG1 antibodies containing λ light chains than those containing κ light chains. These light chain reaction rate differences were replicated in vitro. Additional mechanistic studies showed that base-catalyzed thioether formation through the light chain dehydrogenation was more preferred on antibodies with λ light chains, which may help explain the observed reaction rate differences.

Introduction

The thioether modification on proteins, also called lanthionine, is the result of elimination of one of the sulfur atoms from a disulfide bond (-C-S-S-C-), producing a carbon-sulfur-carbon linkage (-C-S-C-). Originally identified in wool treated with sodium carbonate by Horn et al. in 1941 (1), the modification was shown to form in several other alkali-treated proteins, such as human hair, chicken feathers, and lactalbumin (2, 3). Thioethers were also widely found in foods (4–7) that are treated with heat and alkali as well as in other proteins (8). In addition, the presence of thioethers in human lens proteins from aged, brunescent, and senile cataractous lenses was also reported (9, 10), where their formation may be a function of the aging process.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been the predominant biotherapeutic modality to treat cancers, autoimmune diseases, and other medical conditions over the past decade (11, 12). Much of the product quality monitoring for mAbs is for a variety of localized chemical modifications, known collectively as microheterogeneity. These modifications can form over the lifespan of the molecules, from early on during synthesis to as late as after administration to patients. Microheterogeneity includes deamidations, glycosylation forms, oxidations, N-terminal pyroglutamate formation, glycation, and disulfide heterogeneity (13). The recent “quality by design” (QbD) paradigm requires significant knowledge of a drug's mechanism of action and how the drug's product quality attributes, such as microheterogeneity, affect its quality. Those attributes that must be controlled because they affect the safety or efficacy of the drug are termed critical quality attributes (14, 15).

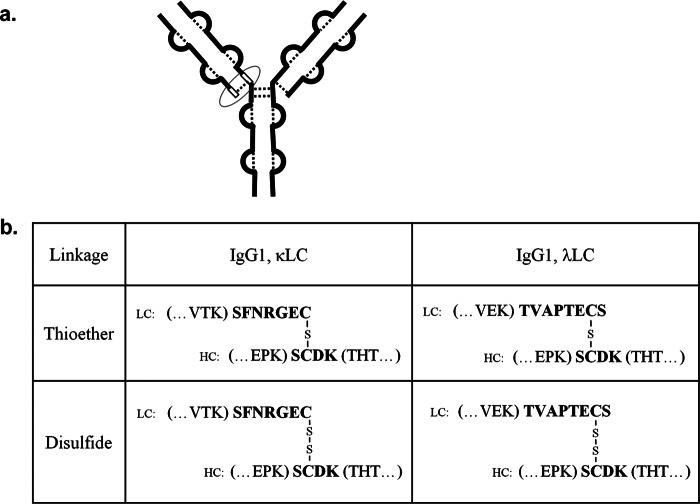

Recently, thioether linkages have been found to form in therapeutic recombinant proteins during production and storage, including monoclonal antibodies (16) and human growth hormone (17, 18). Among the 14 disulfide bonds in IgG1, as shown in Fig. 1a, only one was shown to be somewhat sensitive to thioether formation, the position of the original heavy chain (HC)2 and light chain (LC) disulfide bond, which is at or near the C terminus of the LC. Evidence as to whether this particular thioether is a critical quality attributes has not been published.

FIGURE 1.

Thioether formation site in IgG1 and corresponding peptides after Lys-C digestion. a, the thioether modification site in IgG1 (circled) is located at the site of the former disulfide bond between the LC and HC. The white segments represent the non-reduced peptide used in the thioether analysis. The dotted lines represent disulfide bonds, and the thick lines represent the polypeptide chains. b, primary peptide sequences used to characterize thioether modifications in IgG1κ and IgG1λ after Lys-C digestion are shown.

In this study we sought to measure the thioether levels formed on endogenous antibodies and performed mechanistic studies to help explain how differences arose between antibody samples both in vitro and in vivo. Information obtained here can be considered when assessing the safety impact of this product quality attribute.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Two recombinant human monoclonal IgG1 antibodies with either κ (mAbA) or λ light chain (mAbB) were produced from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and purified at Amgen Inc. Human IgG1 with κ and λ light chains (mIgG1κ and mIgG1λ, respectively), purified from plasma of myeloma patients, were purchased from Sigma. Endogenous IgGs were isolated from the serum of healthy human donors, as described previously (19–21). Endoproteinase Lys-C was obtained from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA). Acetonitrile was from Sigma. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was purchased from Pierce.

Human Pharmacokinetic Study of IgG1κ (mAbA) and Ligand Affinity Purification

A 1000-mg mAbA dose was administered to two adult human patients in a single intravenous injection. Blood samples were collected over several weeks at selected times. After allowing time to clot, the clot was separated from serum by centrifugation. Serum was stored in cryotubes at −20 °C or colder until used. Ligand-based affinity purification was carried out essentially as described before (22, 23). Briefly, a 0.4–0.7-ml aliquot of clarified human serum containing mAb was mixed with 4.5 ml of PBS and 0.2 ml of mAbA-ligand resin and rocked at room temperature for 4 h. After sedimentation and washing with PBS buffer (containing 0.5 m NaCl), the mAb was eluted with 10 mm glycine (pH 1.5) followed by adjusting pH to ∼7.0. Thioether levels were not affected by the affinity purification technique.

Preparation of Stressed Thioether Samples

To accelerate thioether formation in vitro, both recombinant mAbA (IgG1κ) and mAbB (IgG1λ) were incubated in glycine-NaOH buffer at pH 9.1 for 3 days at 55 °C or for 9 days at 45 °C.

Forced Thioether Formation in Deuterium Oxide

50 mm deuterated glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 9.3) was prepared by mixing 2.5 ml of 0.2 m glycine dissolved in D2O with 0.44 ml of 0.2 m NaOH (prepared in D2O). IgG1 antibodies, mAbA and mAbB, were buffer-exchanged into this deuterated buffer to achieve a final concentration of about 3 mg/ml then incubated at 50 °C for 70 h. Antibodies stressed in D2O were digested with endoproteinase Lys-C under non-reducing conditions in H2O solvent to ensure the back-change of labile deuterium atoms.

Non-reduced Lys-C Enzymatic Digestion

To denature the antibodies under non-reducing condition, 50 μl of antibody solutions were mixed with 10 μl of 1.0 m NaH2PO4, 10 μl of 0.4 m NH2OH, 6 μl of 36 mg/ml methionine, and 36 mg urea. Test reactions with N-ethylmaleimide addition (to quench any free thiols) did not affect the results so was not used in the subsequent experiments. After vortexing, 3 μl of 20% TFA was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Before digestion, the denatured antibody mixture was neutralized with 14 μl of 1.0 m NaOH followed by adding 26 μl of water and 1.2 μl of 100 mm EDTA. The pH in these reactions was between 6.5 and 7.0. The digestion reaction was carried out by adding 10 μl of 1 μg/μl Lys-C and incubating the mixture at 37 °C overnight.

pH Profile of Thioether Formation

To determine the pH effects on thioether formation, both mAbA and mAbB were diluted 18-fold to about 3 mg/ml into different buffers to obtain specific pH values. To generate pH of 4 or 5, 0.1 m citrate buffer was used; for pH 6–8, 0.1 m phosphate buffer was used; for pH 9, 50 mm glycine-NaOH buffer was used. The final pH of each sample was measured to be 4.2, 5.1, 5.8, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.1, respectively. Samples were then incubated at 37 °C for 30 days in the dark. Because different thioether formation rates were expected, aliquots of all samples in the pH range of 4–6 were obtained at 7, 21, and 30 days, whereas the aliquots of all samples in the pH range of 8–9 were obtained at 3, 7, 11, and 21 days for analyses.

Thioether Quantification at the Protein Level with LC-MS

RP-HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system with a binary pump and an UV detector at 280 nm. An Agilent Zorbax SB300 C8 column maintained at 75 °C was used to separate antibody LC, HC, and thioether-linked HC to LC. Mobile phase A was 0.1% aqueous TFA, and mobile phase B contained 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile. Components were eluted when applying a linear gradient from 25 to 40% B in 35 min at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. An online intact mass analysis was conducted on a Waters LCT Premier TOF instrument operating in V mode. Raw data were processed using Masslynx MaxEnt 1 software to obtain deconvoluted mass spectra.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Lys-C Digests

The online LC-MS/MS analyses were carried out using either an Agilent 1290 HPLC system or Waters ACQUITY UPLC system coupled with a Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source. The Lys-C digest was injected onto a Waters BEH C18 Column (2.1 × 150 mm, 300 Å pore size, 1.7-μm particle size) with the column temperature maintained at 50 °C. The mobile phase A was 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water, and the mobile phase B was 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile. A gradient (hold at 1% B for 1 min, 1 to 40% B for 120 min) was used to separate the digested peptides at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The eluted peptides were monitored by both UV light (214 nm wavelength) and mass spectrometry. The mass spectrometer was set up to acquire one high resolution full scan at 60,000 resolution (at m/z 400) followed by either a data-dependent scan mode or a pre-selected ion mode. The width for precursor ion isolation was set to 3.0 (m/z) with an activation Q of 0.25 and an activation time of 30 ms. The spray voltage was 4.0–4.5 kV, and the temperature for the heated capillary was 275 °C. The relative thioether modification level was quantified by calculating the ratio of the peak area, extracted from the base peak ion chromatogram corresponding to thioether linked peptide, over the sum of the corresponding peak areas observed for both disulfide- and thioether-linked peptides. Only double-charged ions were used, as single-charged and higher charged species were insignificant.

RESULTS

Characterization and Quantification of Thioether in IgG1

Thioether modifications in antibodies have previously been characterized by capillary electrophoresis-SDS, SDS-PAGE, size exclusion chromatography, and LC-MS/MS. Because peptide mapping provides more detailed information than other techniques, giving not only in depth chemical analyses but site identification, it was used here to characterize thioether modifications in IgG1κ and IgG1λ after protease Lys-C digestions. Consistent with a previous report (16), the major thioether modification site was found to be at the position of the original disulfide linkage between the LC and HC (shown in Fig. 1a). Mozziconacci et al. (24) has demonstrated that UV light could generate a thioether cross-link between the LC cysteine 214 (Eu numbering) close to the C terminus and a HC cysteine 226 (Eu numbering) instead of the HC cysteine 220 (Eu numbering) where original HC-LC disulfide formed in IgG1λ. Moreover, thioether formation at this position was only observed under intense photoirradiation (24) and was not detected in the non-irradiated control.

After proteinase Lys-C digestions, the thioether can be characterized by monitoring MS/MS spectra of the corresponding cross-linked peptides of TVAPTECS (cysteine 214 of LC, Eu numbering) and SCDK (cysteine 220 of HC, Eu numbering) for IgG1λ and of SFNRGEC (cysteine 214 of LC, Eu numbering) and SCDK (cysteine 220 of HC, Eu numbering) for IgG1κ as shown in Fig. 1b. To quantify the relative level of thioether modification, peptide mapping under non-reducing conditions was employed instead of the more common peptide mapping using a chemical disulfide reductant. Thioether levels for IgG1 can be obtained by calculating the ratio of the peak area of thioether-linked peptides over the sum of the thioether- and disulfide-linked peptides. The only chemical difference between disulfide-linked peptide and the thioether variant is the loss of a sulfur atom (Fig. 1b), resulting in a 32-Da loss in mass. Thus, we assume that thioether-containing peptides have the same ionization efficiencies as their corresponding disulfide-linked versions.

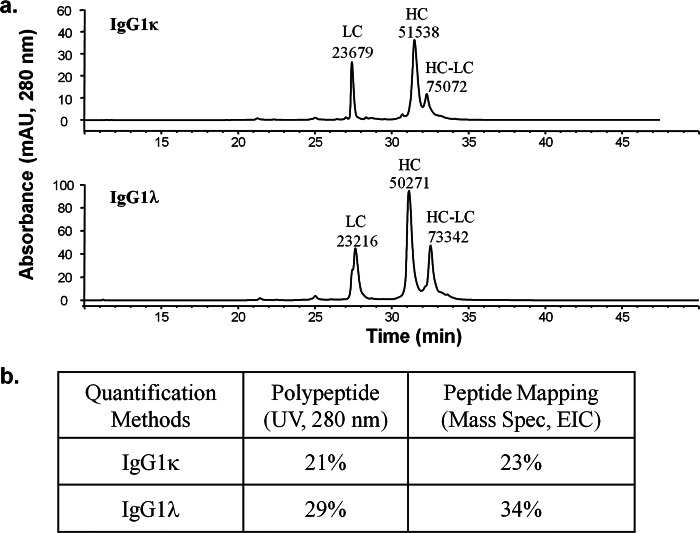

To test this assumption, mAbA and mAbB samples, stressed at high pH to increase thioether levels, were reduced, alkylated, and separated by reversed phase HPLC. The eluate was monitored with UV light (280 nm) and a TOF mass spectrometer, both in-line. Fig. 2a shows the UV traces for the reduced IgG1κ (top panel) and IgG1λ (bottom panel) samples with the elution order being LC and HC followed by the thioether-linked HC-LC polypeptides (non-reducible). Deconvoluted masses of the HC, LC, and thioether-linked HC-LC polypeptides were consistent with theoretical calculations. The relative thioether levels based on UV absorbance at 280 nm were 21 and 29% for mAbA (IgG1κ) and mAbB (IgG1λ), respectively. The stressed antibodies were digested with the protease Lys-C and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Relative thioether levels, based on the extracted peak areas of thioether- and disulfide-linked peptides, were 23% for the IgG1κ and 34% for the IgG1λ sample. Two peaks for the thioether-linked peptide with exactly the same MS MS/MS spectra were observed, consistent with l and d structural isomers at the asymmetric α carbon atom from cysteine residues during thioether formation process. Details of this mechanism will be discussed later. Overall, quantification results based on the two orthogonal methods were consistent (as shown in Fig. 2b), with only slightly higher relative thioether levels using peptide mapping, indicating that the assumption of similar ionization efficiencies for thioether- and disulfide-linked peptides is appropriate for both IgG1κ and IgG1λ. Although both the peptide mapping and undigested LC/MS approaches provided similar results for these examples, there are several advantages to quantifying the thioether using the peptide mapping strategy. First, the peptide map combined with MS provides more selective information, identifying the LC-HC linkage type with the mass associated with the loss of sulfur. Second, due to sequence differences in the LC and HC, the resolution between the HC-LC and HC peaks may not be sufficient for all molecules tested. Finally, the peptide mapping method can be used to quantify thioether in polyclonal IgG1 or even in mixtures of IgG1 and IgG2, whereas these would be obscured in other techniques.

FIGURE 2.

Thioether quantification using polypeptide analysis versus peptide mapping. a, shown is quantification of thioether levels by polypeptide analysis using RP-HPLC with UV absorbance monitoring at 280 nm. The assignment of each peak was confirmed by the intact mass with an online TOF mass spectrometer, with m/z values of 23,679, 51,538, and 75,072 for the LC, HC, and thioether-linked HC-LC, respectively of, IgG1κ (top panel) and with m/z values of 23216, 50,271, and 73,342 for the LC, HC, and thioether-linked HC-LC, respectively, of IgG1λ (bottom panel). b, shown is a comparison of quantification results using peptide mapping (n = 1) with extracted ion chromatograph versus using polypeptide analysis (n = 1) with UV absorbance. The intermediate precision of the peptide mapping assay is 5.0% (average relative standard deviation) based on four sample types tested with at least three independent preparations and analyses.

Yet another advantage of using a non-reducing peptide map quantification strategy is the detection and quantification of another disulfide related modification, the trisulfide. This modification is the result of an additional sulfur atom, likely from hydrogen sulfide, inserting into a disulfide bond (-C-S-S-S-C-). Previous work has identified the LC 214 cysteine-HC 220 cysteine as the major site for this modification in recombinant antibody IgG2 production (25, 26). If trisulfide levels were to become significant, using only thioether and disulfide containing peptides to represent total cross-linked peptides would reduce accuracy. To avoid such artifacts, trisulfide-linked peptides were also monitored throughout this study. For all samples tested here, trisulfide levels were either very low relative to thioether forms or not detected. Thus, only thioether- and disulfide-linked peptides were used for quantification purposes in this study.

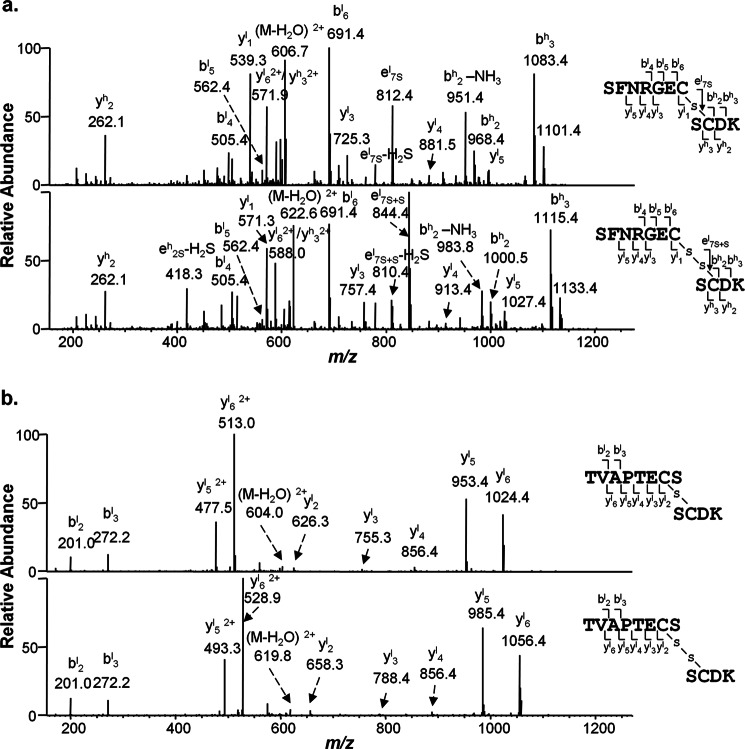

The thioether linkage was identified in MS/MS spectra of thioether-linked peptides of SFNRGEC (LC)/SCDK (HC) from IgG1κ. In the product-ion spectrum of the [M+2H]2+ ion (m/z 615.3, Fig. 3a, top panel), the observed y1l, y3l, y4l y5l ions from the light chain peptide and b2h, b3h ions from the heavy chain peptide exhibited a mass decrease of 32 Da with respect to the masses of the corresponding fragments for the disulfide-linked peptides (Fig. 3a, bottom panel, m/z of 631.3). On the other hand, the masses for b6l, y2h ions were the same as those for disulfide-linked peptide, indicating that thioether modification is formed between two cysteine residues, consistent with the loss of a sulfur atom from the disulfide bond. Moreover, the presence of fragment ions (m/z, 812.4 in Fig. 3a, top panel, and m/z of 844.4 in Fig. 3a, bottom panel) resulting from the fragmentation through thioether or disulfide bond also supports the presence of thioether linkage at that position.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of thioether modifications in IgG1. a, product-ion spectra of the electrospray ionization-produced [M+2H]2+ ions of thioether (top panel)-and disulfide (bottom panel)-linked peptides with an m/z value of 615.3 and m/z of 631.3, respectively, from IgG1 with κ light chain after Lys-C digestion (a) and thioether (top panel)- and disulfide (bottom panel)-linked peptides, respectively with m/z of 612.8 and m/z of 628.8 from IgG1 with λ light chain after Lys-C digestion (b). A scheme summarizing the observed fragment ions for each peptide is shown on the right for each panel.

Like IgG1κ, thioether modification between the HC and LC from IgG1λ was also confirmed by the product-ion spectra of the [M+2H]2+ ions of the thioether- and disulfide-linked peptides of TVAPTECS/SCDK with m/z of 612.8 (Fig. 3b, top panel) and m/z of 628.8 (Fig. 3b, bottom panel), respectively. The m/z values observed for the y2l, y3l, y4l, y5l y6l ions from the light chain peptide TVAPTECS portion in Fig. 3b, top panel, consistently showed a mass difference of 32 Da from those corresponding ions in disulfide-linked tandem mass spectrum, which supports the formation of thioether linkage between HC and LC in IgG1λ. It is also worth noting that most abundant ions of y5l y6l (with both single and double charges) are attributed to the presence of a proline residue in the LC of IgG1λ. Thus, unlike the corresponding thioether-containing peptides in IgG1κ, fragmentation along thioether or disulfide linkage was not observed. On the other hand, we found that MS3 or MS4 of certain product ions could generate such fragmentation during collision-induced dissociation and further confirmed the assignment (data not shown).

Thioether Formation in Vivo

Thioether formation in antibodies has thus far only been reported in recombinant IgG1 molecules (16, 27). To determine whether this modification is naturally occurring on human antibodies, endogenous antibodies were rapidly purified from the serum of six individual healthy human subjects by Protein A affinity chromatography. Even though the purified antibodies were polyclonal in nature, differing in the variable region in primary sequence, thioether-containing peptides in the constant regions, where the major modification site located, could be readily detected and quantified. Moreover, because the thioether-linked peptide sequences from IgG1λ and IgG1κ differed, the relative levels for both antibody types could be quantified in the same subject's sample.

Table 1 lists the results of relative thioether levels from six healthy individuals and from two myeloma patients. Moderate levels were measured in all the endogenous IgG1 antibody samples, with greater levels consistently found in IgG1λ than IgG1κ. The average thioether levels for IgG1λ and IgG1κ were 11.0% (S.D. = 1.5%) and 5.2% (S.D. = 0.8%), respectively. Thioether modifications were not detected at other positions in the constant region. Relative trisulfide modification levels in the same peptide segments were less than 0.1% (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Thioether levels in myeloma proteins and endogenous IgG1 from healthy human subjects

Single samples were run for each analysis. Average represents six individual healthy subjects.

| Source of Antibodies | Subjects | Thioether level in IgG1κ | Thioether level in IgG1λ |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Healthy subjects | #1 | 4.9 | 11.4 |

| #2 | 4.0 | 9.1 | |

| #3 | 5.0 | 9.8 | |

| #4 | 6.2 | 12.6 | |

| #5 | 5.9 | 12.7 | |

| #6 | 5.0 | 10.6 | |

| Average | 5.2 | 11.0 | |

| Myeloma patients | A (IgG1κ) | 2.9 | |

| B (IgG1λ) | 6.7 |

Thioether levels were also monitored in human IgG1 purified from myeloma patients. Because the myeloma proteins preparations are essentially monoclonal because they become the dominant antibody in patient sera, peptide mapping of the isolated myeloma protein allows analysis of thioether bond prevalence at both constant and variable regions in the molecule. Both IgG1λ and IgG1κ myeloma proteins were analyzed by non-reduced peptide mapping with LC-MS/MS. Thioethers were detected only at the disulfide position of the LC-HC linkage. Just like IgG1 from healthy subjects, myeloma IgG1 with λ LC had higher thioether levels than that with κ LC. An interesting observation is that the relative thioether levels in myeloma antibodies were only about half that found in normal endogenous IgG1. The most likely reason is the shorter circulating half-life of myeloma IgG as compared with endogenous polyclonal antibody in healthy adults. Myeloma antibodies have been reported to have an average half-life of 11 days, as compared with 21 days for IgG1 in healthy adults (28). If thioether formation is a post-translational event, thioether levels would be expected to be proportional to time in circulation.

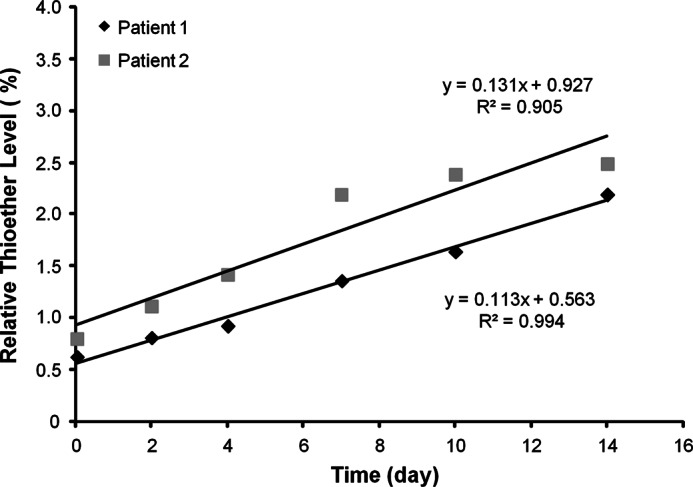

Thioether Level Changes over Time in Human Circulation

To have more accurate and direct measurements of antibody thioether conversion while circulating in blood, the relative levels of thioether were monitored over time after a single-dose intravenous injection of the therapeutic IgG1 antibody mAbA (IgG1κ) in humans (Fig. 4). Thioether levels increased from <1% to ∼2.7% for patient 1 and from 0.5% to about 2.1% for patient 2 over the 14 days tested, for a conversion rate of about 0.1%/day. This rate is roughly consistent with the estimated levels found in endogenous IgG1and the predicted average half-life of antibodies based on published studies.

FIGURE 4.

Time course of thioether formation in vivo. The relative levels of thioether were determined after mAbA (IgG1κ) administration to people.

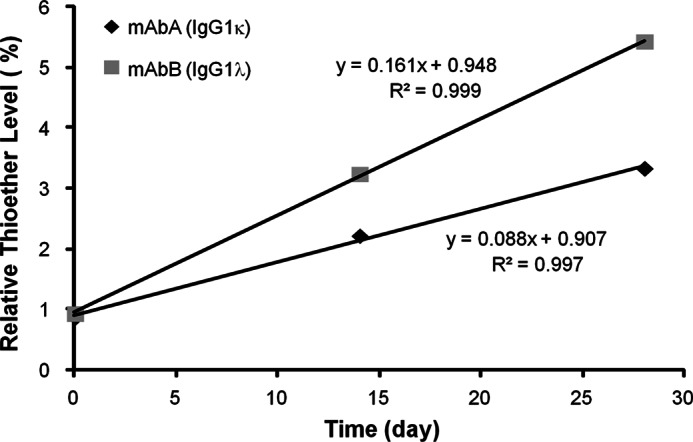

Thioether Formation in Vitro

In vitro incubations were performed to study thioether reaction kinetics and mechanism. MAbA and mAbB were incubated in a PBS buffer at physiological temperature and pH. Time course samples were then analyzed by peptide mapping with LC-MS/MS. As with the in vivo samples, thioether levels increased linearly with time (Fig. 5). MAbA (IgG1κ) conversion in vitro (0.09%/day) was similar to that observed in vivo (0.1%/day), whereas mAbB (IgG1λ) thioether conversion kinetics (0.16%/day) were found to be somewhat faster. With no IgG1λ pharmacokinetic samples available for comparison, in vitro kinetics for this antibody type could only be compared with static endogenous in vivo IgG samples. The ∼2-fold faster conversion kinetics for IgG1λ in vitro over IgG1κ was consistent with the endogenous IgG1 results. This difference observed in vitro also supports the myeloma and polyclonal endogenous antibody differences as being naturally occurring and not an artifact of protein purification or other sample manipulation.

FIGURE 5.

Thioether formation in vitro at physiological temperature and pH. In vitro incubations of mAbA and mAbB in PBS buffer were performed to study thioether reaction kinetics. Single samples were analyzed for each time point shown.

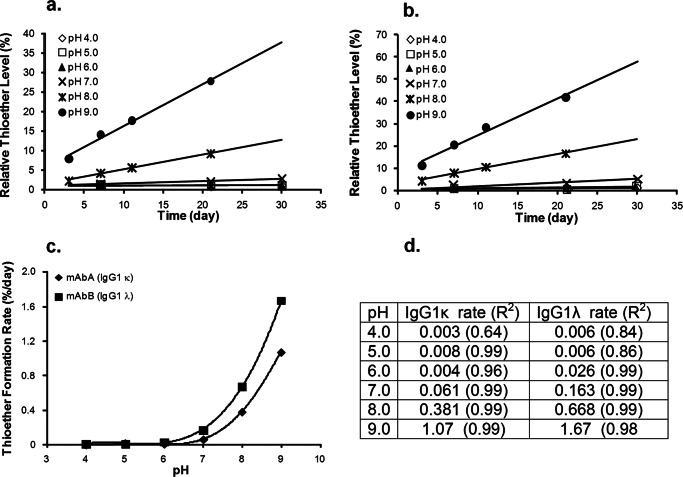

Light Chain Influence on the Thioether Formation Mechanism

A series of experiments were performed in an attempt to determine why the light chain type affects the thioether formation rate. In these we studied the influence of reaction conditions on formation rate and used deuterium incorporation to probe the reaction mechanism. Because thioether modifications on proteins were originally identified in wool and food proteins treated under alkaline conditions, some correlation between pH and reaction rate would be expected. Surprisingly, a detailed study of the pH impact on reaction rate for antibodies and in relation to LC type has not been reported. To test this, the thioether formation rates were measured for mAbA and mAbB incubated in buffers with different pH values. As shown in Fig. 6, thioether levels increased over time for pH values above 6 for IgG1s with either κ (Fig. 6a) or λ (Fig. 6b) light chains. Below pH 6, rates were too low to measure accurately. Thioether formation rates at different pH values for both mAbA and mAbB are summarized in Fig. 6c. The pH profile experiments demonstrated that thioether formation rate for an IgG1 with λ LC was consistently faster than that for an IgG1 with κ LC at all pH values above pH 7, although rate differences between light chain types (IgG1λ/IgG1κ) decreased with increasing pH, and were 2.7 at pH 7, 1.8 at pH 8, and 1.6 at pH 9.

FIGURE 6.

Thioether formation rates at different pH values in IgG1. Shown is thioether formation at the indicated pH value and 37 °C for mAbA (IgG1κ) (a) and mAbB (IgG1λ) (b) c, A plot shows the thioether formation rate versus pH for both IgG1s. Single samples were analyzed. d, rate constants and correlation coefficients (R2) for different pH values.

In two published studies, different but related base-catalyzed reaction mechanisms for thioether formation in antibodies were proposed (29, 30). Although both papers touched on thioether formation, in neither paper was that the main focus of study. Cohen et al. (29) proposed that dehydrogenation (β-elimination) on heavy chain cysteine created dehydroalanine, an intermediate for both thioether formation and fragmentation in the HC hinge region. Specific fragmentation products that they found were consistent with the proposed dehydroalanine intermediate. Amano et al. (30) studied base catalyzed racemization on IgG1κ and found that it occurred exclusively on the HC. They proposed that a reversible ring structure with conjugated double bonds formed on the HC. This intermediate might then proceed to thioether product through other intermediates. Their main evidence was that the incorporation of single deuterium atom (+1 Da) in reactions with heavy water (D2O) was found on the HC cysteine linked to the LC but not on the light chain cysteine involved in that disulfide bond or on other cysteines in the molecule.

In an effort to obtain greater mechanistic understanding of the role that the light chain type plays in the thioether formation reaction, both mAbA (IgG1 with κ LC) and mAbB (IgG1 with λ LC) were incubated in D2O solutions at high pH. Stressed samples were then placed in water after the reactions to allow back exchange of any deuterium associated with labile atoms, such as backbone amides (31) but not deuterium atoms on α-carbon. If dehydrogenation (and subsequent hydrogenation) takes place on the α-carbon of a cysteine residue as part of the thioether reaction mechanism (as proposed in Fig. 9), a deuterium atom will be incorporated on that cysteine α-carbon and, thus, cause a mass increase of 1 Da compared with the control samples (stressed in H2O). The results from this set of experiments were expected to provide clues to why IgG1 with a λ LC has more thioether formed than that with κ LC for both endogenous samples as well as those in vitro generated samples for pH profile experiments.

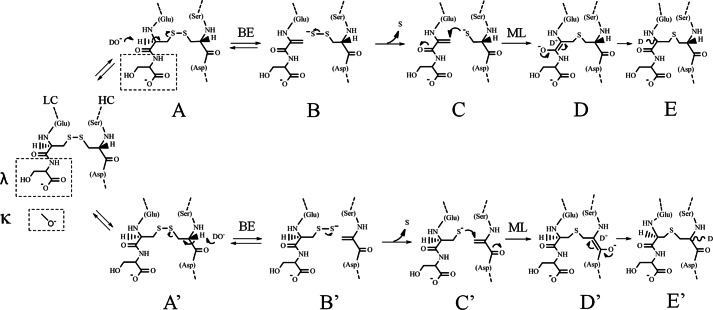

FIGURE 9.

Proposed reaction mechanism of thioether formation in IgG1. The reaction proceeds through dehydrogenation on the light chain cysteine α-carbon (top) or the heavy chain cysteine α-carbon (bottom). The site of deuterium incorporation is shown for reactions proceeding in D2O buffer. The boxes depict the extended portion of the IgG1λ LC due to an additional serine or the oxygen present from the terminal cysteine on the IgG1κ LC. The reaction is shown for an IgG1λ. The exact nature of many of these intermediates is unknown. BE, β-elimination; ML, Michael-type addition.

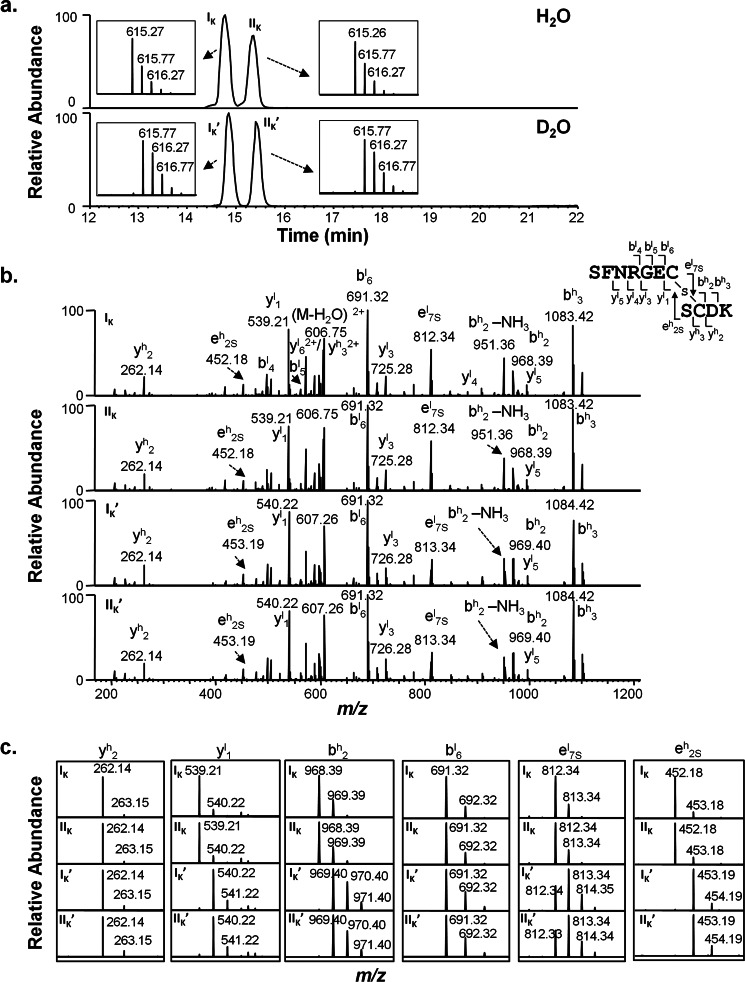

Fig. 7a shows extracted base peak spectra from thioether-linked peptide of mAbA (IgG1κ) reacted at high pH in H2O (top panel) and D2O buffers (bottom panel). Two main peaks were observed for both antibodies, with another minor peak seen for mAbB (Fig. 8a). This peak splitting may be due to racemization at the cysteines, as observed in the disulfide-linked peptides (29, 30), though no effort was made here to confirm this. These chromatographic peaks are shown in the main figure, with the expanded MS spectra with isotopic distributions for peaks IK, IIK, IK′, and IIK′ provided in insets. The thioether-containing peptide from mAbA was mainly 1 Da larger for the D2O incubations as expected, with m/z of 615.8, as compared with those obtained in H2O buffer with m/z of 615.3 for double-charge ions. To determine the location of the deuterium incorporation, tandem mass spectra (Fig. 7, b and c) were acquired for both deuterium-labeled and unlabeled thioether containing peptides found in peaks IK, IIK, IK′, and IIK′. The same b6l and y2h masses were observed independent of deuterium incorporation in the precursor ions, indicating that no deuterium was incorporated into the light chain segment of SFNRGE or heavy chain DK residues. In contrast, the deuterium labeling process introduced an additional 1-Da mass increase for the isotopic peaks of y1l and b2h, besides y3l, y4l, y5l, and b3h ions. These results indicated that the deuterium atom was likely localized to the cysteine residues. Furthermore, the isotopic distribution changes for peaks IK′ and IIK′ when compared with peaks IK and IIK for e7Sl ion and e2Sh ions, which were generated due to the fragmentation on opposite sides of the thioether sulfur atom, demonstrated that the HC cysteine was the major deuterium incorporation site. In addition, some deuterium incorporation on the LC cysteine was observed as indicated by e7Sl, although some partial deuterium transfer between the HC and LC cysteine α-carbons during the CID fragmentation process could not be ruled out.

FIGURE 7.

Deuterium incorporation in cysteine residues in stressed mAbA (IgG1κ) samples. a, shown are extracted base peak spectra of thioether-linked peptides from mAbA stressed in H2O (top panel) and D2O buffers (bottom panel). Expanded mass spectra with isotopic distributions of corresponding peptides eluted as four main peaks of IK, IIK, IK′, and IIK′ were shown as insets. b, shown are product-ion spectra of the electrospray ionization-produced [M+2H]2+ ions of thioether-linked peptides eluted from peaks IK, IIK, IK′, and IIK′ as shown in Fig. 7a, with m/z values of 615.3 and 615.8 from mAbA stressed in H2O solvent (top panel) and D2O solvent, respectively (bottom panel), after Lys-C digestions. c, shown are expanded mass spectra of major fragment ions with isotopic distribution observed in the MS/MS spectra shown in Fig. 7b. A scheme summarizing major observed fragment ions from MS/MS of corresponding peptides is shown on the right of b.

FIGURE 8.

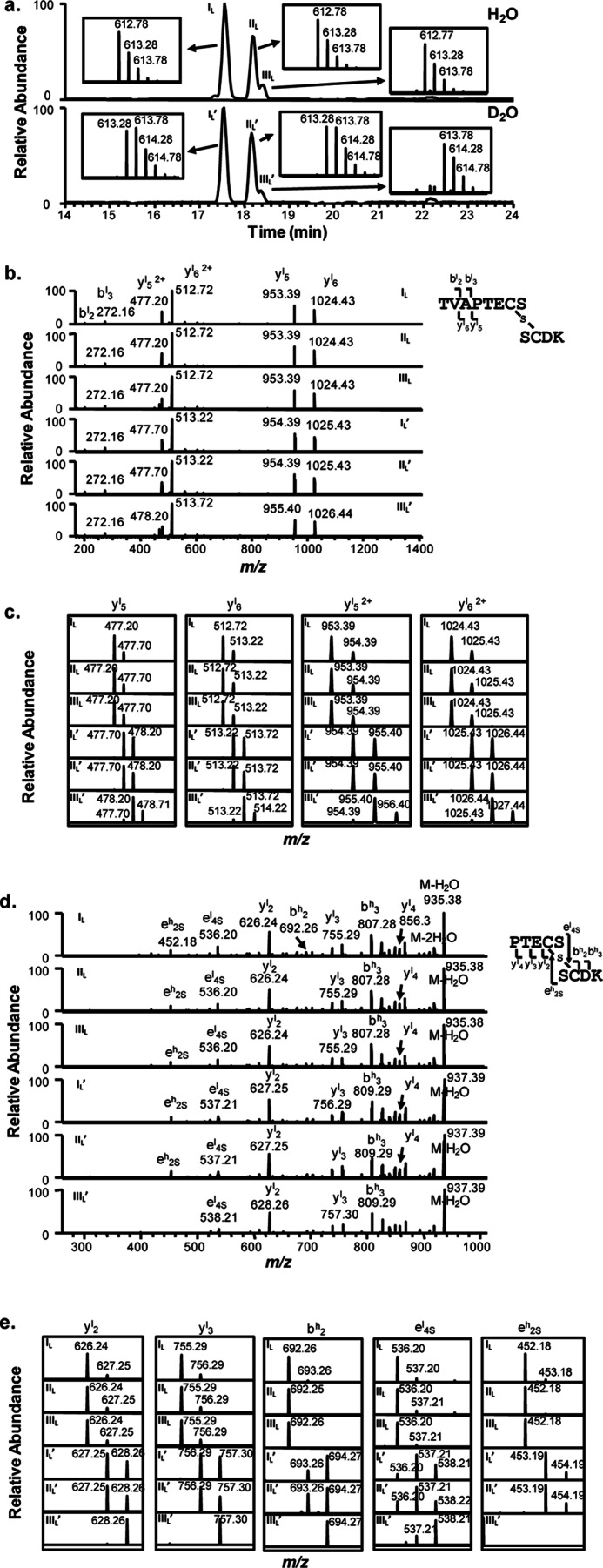

Deuterium incorporation in cysteine residues in stressed mAbB (IgG1λ) samples. a, shown are extracted base peak spectra of thioether-linked peptides from mAbB stressed in H2O (top panel) and D2O buffers (bottom panel). Expanded mass spectra with isotopic distributions of the corresponding peptides eluted as four main peaks of IL, IIL, IL′, and IIL′, and two small peaks of IIIL and IIIL′ are shown as insets. b, shown are product-ion spectra of the electrospray ionization-produced [M+2H]2+ ions of thioether-linked peptides eluted in peaks IL, IIL, IIIL, IL′, IIL′, and IIIL′ as shown in a, with m/z values of 612.8 and 613.3 from mAbB stressed in H2O solvent (top panel) and D2O solvent (bottom panel) after Lys-C digestion, respectively. c, shown are expanded mass spectra of major fragment ions with isotopic distribution observed in the MS/MS spectra of b. A scheme summarizing the major fragment ions observed in the MS/MS spectra is shown on the right of b. d, MS3 mass spectra of single charged yl5 ions with m/z of 953.4 (top three panels) and 954.4 (bottom three panel). e, shown are expanded mass spectra of major fragment ions with the isotopic distribution observed in the MS3 spectra of c. A scheme summarizing major observed fragment ions from MS3 mass spectra is shown on the top right of d.

Similarly, extracted base peak spectra of the thioether-linked peptide from mAbB (IgG1λ) stressed in H2O (top panel) and D2O buffers (bottom panel) are shown in Fig. 8a, with the expanded mass spectra showing isotopic distributions of the peptides found in peaks IL, IIL, IIIL, IL′, IIL′, and IIIL′ as insets. As expected, the main component in peaks IL′ and IIL′ shows a mass increase of 1Da as compared with peaks IL and IIL. It is worth noting that a mass increase of a 2-Da peak was also observed for the two main peaks of IL′ and IIL′, based on their isotopic distribution patterns. In addition, a minor peak (labeled as IIIL′ in Fig. 8a, bottom panel) clearly showed a 2-Da increase when compared with the control (peak IIIL, top panel).

The tandem mass spectra of corresponding peptides from mAbB (IgG1λ) were also acquired, as shown in Fig. 8, b and c. Fewer major ions were observed, preventing the precise localization of the deuterium atom based on MS2 alone. To overcome this limitation, we performed MS3 on the single-charged y5l product ion (shown in Fig. 8, d and e). The observed y2l and b2h ions in MS3 spectra suggested that the deuterium atom was likely incorporated in the cysteine residues, and the isotopic distribution of fragment ions e4Sl and e2Sh, which were generated due to the cleavages immediately on either side of the thioether sulfur (diagram Fig. 8d), indicated that a significant fraction of the deuterium was incorporated in both the HC and LC cysteines. The 2-Da mass shift in the precursor ion from peak IIIL′ and subsequent tandem MS spectra indicate that this peptide contains deuterium incorporation on both the LC and HC cysteines.

Taken together, these results suggest that thioethers form by dehydrogenation either through the HC or LC cysteine residue for both IgG1λ and IgG1κ, although the reaction through HC is more dominant for IgG1κ. This is consistent with a reaction that proceeds at a particular rate through the HC but is inhibited on κ LCs, where the would-be reactive cysteine is the terminal residue. Extension of the LC in the λ type, with one additional residue beyond cysteine, allows more dehydrogenation to proceed through this chain, with the result being a faster overall thioether formation rate on λ-containing IgG1s.

DISCUSSION

The thioether (or lanthionine) linkage has been reported in recombinant monoclonal antibodies (16) and recombinant human growth hormone (17, 18) as well as in wheat proteins treated with alkaline pH and at a high temperature (6). Although the thioether bond occurs naturally in certain peptide and protein antibiotics and in body organs and tissues (5), its presence in a normal endogenous human protein had not been reported. Human IgG1 has 4 interchain disulfide bonds and 12 intrachain disulfide bonds. The only thioether linkage that was observed in this study, as well as in a previous report (16, 29, 30), was between the HC and LC, although thioether linkages have been reported at other sites of IgG1 exposed to UV light (24). In this study we report that thioether is a naturally occurring modification, with 11% of endogenous IgG1λ and 5% of endogenous IgG1κ containing thioethers at this one position in the molecule. Thioether linkages were also observed in the LC-HC positions of IgG2 (not shown), although disulfide isoform heterogeneity, which is the result of alternative LC-HC linkages, makes quantification of the thioether levels by the methods described here more complex.

Assessing the criticality of monoclonal antibody product quality attributes through clinical studies has been discussed in detail by Goetze et al. (14). One tool in the assessment is the analysis of attribute formation in the drug upon administration to patients. Similar to this, Yin et al. (27) monitored changes to an IgG1 after injection in rats. A peak, consistent with a non-reducible HC-LC heterodimer, grew in abundance with time after injection. This result is consistent with thioether formation at the position in the molecule described here and in a previous publication (16), although the presence of other non-reducible cross-linked species other than thioether linkage could not be excluded. Additional non-reducible peaks were observed in their electropherograms, which were not characterized or explained (27).

Our results, monitoring a therapeutic antibody in humans, revealed that the disulfide bond between the HC and LC was converted to a thioether linkage at an average rate about 0.1%/day for an IgG1κ, in agreement with the rate from our physiological in vitro incubation study but somewhat slower than the non-reducible species measured in the Yin et al. (27) study, where IgG1 with a λ LC was employed. The observation that IgG1λ thioether formation in vitro was faster, at 0.2%/day under the same pH and temperature conditions, explains the higher relative thioether level on endogenous IgGλ versus endogenous IgG1κ and the levels found in myeloma proteins differing in light chain type. The faster conversion in IgGλ results in higher thioether levels, with the assumption that the clearance rates were similar.

In Fig. 9, we propose a base catalyzed thioether reaction mechanism for IgG1 that best accounts for the observations described here and elsewhere. The basic features are similar to those proposed by Cohen et al. (29), with additional elements to highlight the influence of LC type on the reaction. Under appropriate conditions, a disulfide bond can undergo reversible β-elimination, transforming a cysteine residue into dehydroalanine. This species is relatively unstable and susceptible to nucleophilic attack by an adjacent cysteine residue to form a thioether bond (32–34) or reformation of the disulfide. Reformation of the disulfide bond also results in rehydrogenation and can be observed by deuterium incorporation on the cysteine (Ref. 30 and data not shown) and racemization. As depicted, β-elimination and Michael-type addition may occur on either the LC (top) or HC (bottom) to produce the products we observed (species E and E′). IgG1κ and IgG1λ are capable of undergoing dehydrogenation on both the HC and LC, but the degree of deuterium incorporation on the LC (and the faster overall rate) suggests that the LC reaction is more favorable for IgG1 with λ LCs than those with κ LCs. One possible explanation for a greater bias toward HC dehydrogenation on IgG1κ (and lower reaction rate) is that charge repulsion between the LC C-terminal carboxyl group on the κ LC and the attacking base (Fig. 9, upper reaction, intermediate A) makes dehydroalanine formation on the LC less favorable with IgG1κ. Boxes with dashed lines in the reaction scheme represent the differences in the LC C terminus containing an additional serine residue (λ) or lacking one (κ). Distances between the terminal carboxyl group and the base are expected to be shorter with a terminal cysteine (on κ LC) than with a penultimate cysteine residue (on λ LC). In contrast, dehydrogenation rates on the HC (lower reaction) might be expected to be similar between antibodies with different LC type.

Because dehydroalanine has been proposed as an intermediate in both thioether formation and HC hinge fragmentation (29), one might expect increased fragmentation in our base-stressed samples. A search of reduced HPLC-MS chromatograms shown in Fig. 2a as well as the non-reduced peptide maps indicated little hinge cleavage. In addition, no new peptides were observed in the non-reduced peptide map that would indicate cleavage or disulfide scrambling. Perhaps the conditions used to generate thioether in this work (3 days, pH 9, 55 °C) are too mild as compared with those used to generate Fc fragmentation (17 days, pH 8, 45 °C). We should also note that Cohen et al. (29) used techniques (SEC and SDS-PAGE) to enrich for the fragments of interest, so the overall levels were not discussed.

An alternative reaction mechanism has been proposed by Amano et al., where a cyclic imidazoline forms before rearrangements and Michael-like addition (29, 30). Their scheme attempted to account for racemization uniquely occurring at the cysteine 220 of the HC, the residue involved in the HC-LC disulfide bond. Only a single deuterium was incorporated per molecule in their stress studies and only at this one HC cysteine. Because dehydrogenation would only occur at the HC cysteine, only would that intermediate proceed to a thioether product. In the present work we provided evidence that dehydrogenation occurs on both the LC and HC cysteine, with more LC dehydrogenation on the λ LC cysteine. One possible explanation for the different observations is that the Amano et al. (30) study was performed with an IgG1κ antibody, where the dehydrogenation on the LC would be expected to be lower. Another possibility is that both cyclic imidazoline on the HC and dehydroalanine on HC and LC can form under similar stress conditions. Dehydrogenation and, thus, racemization would be expected to be reversible, as shown in the proposed reaction scheme. If this step proceeds faster than overall thioether formation and can occur on both the LC and HC, deuterium incorporation would be expected on both the HC and LC cysteines on the same thioether product. We observed +2-Da incorporations on the thioether-containing peptides, with more found on the IgG1λ. This observation is consistent with dehydrogenation occurring primarily on the HC for IgG1κ and a greater amount occurring on the LC for IgG1λ.

Other chemical reaction differences have been attributed to antibody light chain type. Specifically, the disulfide bond between HC and LC for IgG1λ is more susceptible to reduction than that for IgG1 with κ light chain (35). Further experiments using IgG1λ as well as two variants (one with the Ser replaced by Ala and one with the Ser residue deleted) indicated that an extra C-terminal residue significantly impacted interchain disulfide reduction (36). The authors of that study proposed that the redox potential of disulfide bond was affected by the proximity of the light chain C-terminal carboxylic group. This site is the most sensitive to reduction, indicating its greater solvent exposure. Racemization and thioether formation at this site may be due more to the consequences of solvent exposure and flexibility than to unique features of the HC sequence surrounding this site.

Monitoring of product quality attributes such as thioether moieties during manufacturing and storage is typically performed to ensure the safety and efficacy of therapeutic proteins. Lot-to-lot variations in attribute levels are often controlled due to concerns that higher levels may pose a safety risk, such as a greater immunogenic potential. For the antibody thioether modification, knowledge that it is naturally occurring and in a conserved region of the molecule can be taken into account when assessing its safety risk. Impact of the thioether modification on antibody efficacy is another potential concern but was not examined here. Although the modification is physically distant from the antigen binding site, the shorter bond length could potentially affect activity by changing Fab orientation. This change would more likely affect antibodies whose mechanism of action required the simultaneous binding of two targets with rigid orientations, such as cell surface receptors, but would need to be determined on a case by case basis.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable contribution of Dr. Andy Goetze throughout the in vivo studies and the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Chris Fotsch, Diana Liu, Jane Yang, Lizy Tang, and Tian Wang for assistance and discussions.

Footnotes

- HC

- heavy chain

- LC

- light chain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Horn M. J., Jones D. B., Ringel S. J. (1941) Isolation of a new sulfur-containing amino acid (lanthionine) from sodium carbonate-treated wool. J. Biol. Chem. 138, 141–149 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horn M. J., Jones D. B. (1941) The isolation of lanthionine from human hair, chicken feathers, and lactalbumin. J. Biol. Chem. 139, 473 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horn M. J., Jones D. B., Ringel S. J. (1942) Isolation of mesolanthionine from various alkali-treated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 144, 87–91 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han Y., Parsons C. M. (1991) Protein and amino acid quality of feather meals. Poult. Sci. 70, 812–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friedman M. (1999) Chemistry, biochemistry, nutrition, and microbiology of lysinoalanine, lanthionine, and histidinoalanine in food and other proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47, 1295–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lagrain B., De Vleeschouwer K., Rombouts I., Brijs K., Hendrickx M. E., Delcour J. A. (2010) The kinetics of β-elimination of cystine and the formation of lanthionine in gliadin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 10761–10767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rombouts I., Lagrain B., Brijs K., Delcour J. A. (2010) β-Elimination reactions and formation of covalent cross-links in gliadin during heating at alkaline pH. J. Cereal Sci. 52, 362–367 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tou J. S., Violand B. N., Chen Z. Y., Carroll J. A., Schlittler M. R., Egodage K., Poruthoor S., Lipartito C., Basler D. A., Cagney J. W., Storrs S. B. (2009) Two novel bovine somatotropin species generated from a common dehydroalanine intermediate. Protein J. 28, 87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bessems G. J., Rennen H. J., Hoenders H. J. (1987) Lanthionine, a protein cross-link in cataractous human lenses. Exp. Eye Res. 44, 691–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linetsky M., Hill J. M., LeGrand R. D., Hu F. (2004) Dehydroalanine cross-links in human lens. Exp. Eye Res. 79, 499–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maggon K. (2007) Monoclonal antibody “gold rush.” Curr. Med. Chem. 14, 1978–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weiner L. M., Surana R., Wang S. (2010) Monoclonal antibodies. Versatile platforms for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 317–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu H., Gaza-Bulseco G., Faldu D., Chumsae C., Sun J. (2008) Heterogeneity of monoclonal antibodies. J. Pharm. Sci. 97, 2426–2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goetze A. M., Schenauer M. R., Flynn G. C. (2010) Assessing monoclonal antibody product quality attribute criticality through clinical studies. MAbs 2, 500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rathore A. S. (2009) Roadmap for implementation of quality by design (QbD) for biotechnology products. Trends Biotechnol. 27, 546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tous G. I., Wei Z., Feng J., Bilbulian S., Bowen S., Smith J., Strouse R., McGeehan P., Casas-Finet J., Schenerman M. A. (2005) Characterization of a novel modification to monoclonal antibodies. Thioether cross-link of heavy and light chains. Anal. Chem. 77, 2675–2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lispi M., Datola A., Bierau H., Ceccarelli D., Crisci C., Minari K., Mendola D., Regine A., Ciampolillo C., Rossi M., Giartosio C. E., Pezzotti A. R., Musto R., Jone C., Chiarelli F. (2009) Heterogeneity of commercial recombinant human growth hormone (r-hGH) preparations containing a thioether variant. J. Pharm. Sci. 98, 4511–4524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Datola A., Richert S., Bierau H., Agugiaro D., Izzo A., Rossi M., Cregut D., Diemer H., Schaeffer C., Van Dorsselaer A., Giartosio C. E., Jone C. (2007) Characterisation of a novel growth hormone variant comprising a thioether link between Cys-182 and Cys-189. Chem. Med. Chem. 2, 1181–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu Y. D., van Enk J. Z., Flynn G. C. (2009) Human antibody Fc deamidation in vivo. Biologicals 37, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flynn G. C., Chen X., Liu Y. D., Shah B., Zhang Z. (2010) Naturally occurring glycan forms of human immunoglobulins G1 and G2. Mol. Immunol. 47, 2074–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pan H., Chen K., Pulisic M., Apostol I., Huang G. (2009) Quantitation of soluble aggregates in recombinant monoclonal antibody cell culture by pH-gradient protein A chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 388, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goetze A. M., Liu Y. D., Zhang Z., Shah B., Lee E., Bondarenko P. V., Flynn G. C. (2011) High-mannose glycans on the Fc region of therapeutic IgG antibodies increase serum clearance in humans. Glycobiology 21, 949–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Y. D., Chen X., Enk J. Z., Plant M., Dillon T. M., Flynn G. C. (2008) Human IgG2 antibody disulfide rearrangement in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29266–29272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mozziconacci O., Kerwin B. A., Schöneich C. (2010) Exposure of a monoclonal antibody, IgG1, to UV-light leads to protein dithiohemiacetal and thioether cross-links. A role for thiyl radicals? Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23, 1310–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gu S., Wen D., Weinreb P. H., Sun Y., Zhang L., Foley S. F., Kshirsagar R., Evans D., Mi S., Meier W., Pepinsky R. B. (2010) Characterization of trisulfide modification in antibodies. Anal. Biochem. 400, 89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pristatsky P., Cohen S. L., Krantz D., Acevedo J., Ionescu R., Vlasak J. (2009) Evidence for trisulfide bonds in a recombinant variant of a human IgG2 monoclonal antibody. Anal. Chem. 81, 6148–6155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yin S., Pastuskovas C. V., Khawli L. A., Stults J. T. (2013) Characterization of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies reveals differences between in vitro and in vivo time-course studies. Pharm. Res. 30, 167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morell A., Terry W. D., Waldmann T. A. (1970) Metabolic properties of IgG subclasses in man. J. Clin. Invest. 49, 673–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen S. L., Price C., Vlasak J. (2007) β-Elimination and peptide bond hydrolysis. Two distinct mechanisms of human IgG1 hinge fragmentation upon storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6976–6977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amano M., Hasegawa J., Kobayashi N., Kishi N., Nakazawa T., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2011) Specific racemization of heavy-chain cysteine 220 in the hinge region of immunoglobulin γ1 as a possible cause of degradation during storage. Anal. Chem. 83, 3857–3864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang L., Lu X., Gough P. C., De Felippis M. R. (2010) Identification of racemization sites using deuterium labeling and tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 6363–6369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Earland C., Raven D. J. (1961) Lanthionine formation in keratin. Nature 191, 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Florence T. M. (1980) Degradation of protein disulphide bonds in dilute alkali. Biochem. J. 189, 507–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nashef A. S., Osuga D. T., Lee H. S., Ahmed A. I., Whitaker J. R., Feeney R. E. (1977) Effects of alkali on proteins. Disulfides and their products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 25, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu H., Chumsae C., Gaza-Bulseco G., Hurkmans K., Radziejewski C. H. (2010) Ranking the susceptibility of disulfide bonds in human IgG1 antibodies by reduction, differential alkylation, and LC-MS analysis. Anal. Chem. 82, 5219–5226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu H., Zhong S., Chumsae C., Radziejewski C., Hsieh C. M. (2011) Effect of the light chain C-terminal serine residue on disulfide bond susceptibility of human immunoglobulin G1λ. Anal. Biochem. 408, 277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]