Background: Kir2.1 channels are uniquely activated by PI(4,5)P2 and can be inhibited by other PIPs.

Results: A different subset of residues controls channel binding to each PIP. PIPs can encompass multiple orientations in two sites.

Conclusion: Selective activation by PI(4,5)P2 involves orientational specificity, and other PIPs inhibit through direct competition.

Significance: Our findings reveal unanticipated complexities of PIP interactions.

Keywords: Lipids, Molecular Docking, Molecular Modeling, Phosphatidylinositol Phosphatase, Potassium Channels

Abstract

Kir2.1 channels are uniquely activated by phosphoinositide 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) and can be inhibited by other phosphoinositides (PIPs). Using biochemical and computational approaches, we assess PIP-channel interactions and distinguish residues that are energetically critical for binding from those that alter PIP sensitivity by shifting the open-closed equilibrium. Intriguingly, binding of each PIP is disrupted by a different subset of mutations. In silico ligand docking indicates that PIPs bind to two sites. The second minor site may correspond to the secondary anionic phospholipid site required for channel activation. However, 96–99% of PIP binding localizes to the first cluster, which corresponds to the general PI(4,5)P2 binding location in recent Kir crystal structures. PIPs can encompass multiple orientations; each di- and triphosphorylated species binds with comparable energies and is favored over monophosphorylated PIPs. The data suggest that selective activation by PI(4,5)P2 involves orientational specificity and that other PIPs inhibit this activation through direct competition.

Introduction

Inward rectifier potassium (Kir)4 channels are integral membrane proteins that selectively control the permeation of K+ ions across cell membranes. Members of this family are directly regulated by phosphoinositides (PIPs) even in the absence of other proteins or downstream signaling pathways (1–4). Some members show variable specificity for the activating PIP, but all eukaryotic Kir channels are activated by PI(4,5)P2 (2), and members of the Kir2 subfamily, including human Kir2.1 channels, are quite selectively activated by this ligand (2, 5). To understand why Kir2.1 channels are selectively activated by PI(4,5)P2 over other PIPs, it is necessary to identify the location and structure of the PIP binding site(s). Many previous studies have used mutagenesis combined with electrophysiology or biochemical assays on GST fusions of isolated channel domains to identify molecular determinants of PI(4,5)P2 regulation (6–11). Such studies have suggested that numerous positively charged residues in the N and C termini determine sensitivity of Kir2.1 channels to PI(4,5)P2 activation (7, 12–18). Recently, the atomic structures of Kir2.2 (19) and Kir3.2 bound to PI(4,5)P2 (41) have been solved. These reveal one specific site, formed at the interface of N- and C-terminal domains, just beyond the transmembrane segments and clearly involving some of the key residues previously identified as controlling PI(4,5)P2 sensitivity.

However, these structures provide no insight into the energetic contributions of the various residues to ligand binding nor explain how multiple residues outside the binding pocket may affect activation. They also leave unexplained the unique sensitivity of Kir2.1 channel activity to PI(4,5)P2 over other PIPs. Using direct binding approaches on full-length Kir2.1 channels, we identify the energetic contribution of specific residues to binding of multiple PIP ligands and for the first time distinguish them from residues that when mutated primarily act to alter channel gating. This analysis reveals that there is a different subset of residues that when mutated disrupts binding of each PIP. We developed homology models of human Kir2.1 channels based on the PI(4,5)P2-bound structure of chicken Kir2.2 channels and employed ligand docking approaches to identify and compare putative binding sites and conformations for each phosphoinositide. These studies reveal that all PIPs bind within the same general pocket but with different conformational orientations and rotational freedom, suggesting an explanation for why Kir2.1 channels are selectively activated by PI(4,5)P2, and the molecular basis of competitive inhibition of PI(4,5)P2-dependent Kir2.1 channel activity by other PIPs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Human Kir2.1 Protein Purification

WT and mutant Kir2.1-FLAG-His8 fusion proteins were expressed in and purified from the FGY217 strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as described previously (2, 5, 20, 45). Mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing. All mutant channel proteins peaked in the same fractions as WT Kir2.1 channels on gel filtration profiles (supplemental Fig. 1A, dashed lines), and only protein in these three 0.5-ml fractions was used for functional and binding assays.

86Rb+ Uptake Assay

Channel activity and lipid dependence were assessed by measuring 86Rb+ uptake into proteoliposomes containing reconstituted Kir2.1 protein as described previously (2, 20, 45). Valinomycin was used to measure maximal 86Rb+ uptake. Uptake counts measured after reaching a plateau (typically 60 min after commencing the assay (2, 20, 45) were subtracted from uptake counts measured from protein-free liposomes and expressed relative to valinomycin-induced uptake counts. Counts were then renormalized to counts from proteoliposomes made with 0.01% PI(4,5)P2 to determine the lipid-activity relationship quantitatively.

Electrophysiology of Human Kir2.1 in Giant Liposomes

Giant liposomes were prepared using a dehydration-rehydration method in a manner similar to that described previously (2, 5). For patch clamp, giant proteoliposomes were pipetted onto a glass coverslip in an oil-gate chamber(22) and allowed to settle for ∼5 min before starting the solution exchange to wash away debris. Patch clamp recordings were performed in symmetrical K-MOPS buffer (10 mm MOPS acid, 150 mm KCl, pH 7.4 with KOH). Membrane patches were voltage clamped using a CV-4 headstage, an Axopatch 1-D amplifier, and a Digidata 1322A digitizer board (MDS Analytical Technologies). Patch pipettes were pulled from soda lime glass microhematocrit tubes (Kimble) to a resistance of ∼1–3 megohms, and data were collected at a sampling rate of 10 kHz, with a 1-kHz low pass analog filter. Analysis was performed using the pClamp 9.2 software suite (MDS Analytical Technologies) and Origin7.0 (Microcal).

Phosphoinositide Binding Assay

Binding of channel proteins to various PIPs was assessed using PIP Arrays (Echelon Biosciences Inc.) similar to methods described previously (23). Briefly, PIP Arrays were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TBK-T (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm KCl, 0.06% Tween 20) supplemented with 1% BSA. Blocking buffer was replaced, and PIP Arrays were incubated with purified Kir2.1 protein (10 μg/ml) overnight at 4 °C. Following three washes in TBK-T for 15 min each, PIP Arrays were probed using anti-His Probe (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:1000 in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Following three more washes in TBK-T, blots were developed on film and scanned images analyzed by densitometry using ImageJ software. Background was subtracted for each PIP (using the lowest value spot for each PIP as an estimate) and densities measured within a PIP Array were normalized to the 100 pmol/spot for PI(5)P as an internal control. To minimize overinterpretation of data, densities were not compared from different arrays without this normalization. Experiments were performed at least twice for each protein with similar results; however, for the sake of clarity, densitometry data are shown for one set of these experiments. Only when a mutation caused a reduction of binding to a spot on the array with intensity <50% of the average for the remaining spots was the mutation considered to have a meaningful effect on binding.

Homology Modeling of Human Kir2.1 Channels

Homology models of human Kir2.1 were built based on tetrameric template structures including the chicken Kir2.2 (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID codes 3JYC, 3SPC, and 3SPI) crystal structures and mouse Kir3.2 (PDB ID code 3SYQ) open model. Sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW. One hundred homology models were generated through random seeding using the MODELLER 9.10 program (24, 25) for each template structure. Due to high sequence homology (76 and 56% sequence identity or 90 and 78% positive substitutions to chicken Kir2.2 and mouse Kir3.2, respectively), each model was structurally highly similar (1.68–3.07 Å all atom root mean square deviation, 0.21–0.37 Å Cα root mean square deviation) to the template structures in regions where electron density was observed in the crystal structures. However, two missed loops, one that connects the N-terminal β-strand and the sliding helix, and one that connects the two transmembrane α-helices, varied between models. A few derived models that had unphysical bond length and/or bond angle, particularly in Gln residues, were detected and discarded. PDBQT structure files, containing charge and atom type were generated from the PDB file of every homology model beginning with protonation, assigning Gasteiger charge, merging of nonpolar hydrogen to the bonded carbon atom, and assigning atom type using Autodock Tool 1.5.4 (26), and then the protein was aligned to the initial crystal structure using MacPyMOL programs (PyMOL) so that the docking search area was consistent between models. Homology models of mutant Kir2.1 channels were generated in the same way, with Arg80, Arg82, Lys182, Lys185, Lys187, and Lys188 mutated to glutamine individually.

Docking Simulations

Ligand Preparation

Previous studies have experimentally shown that the head groups are critical determinants for PIP activations with the Kir protein (Fig. 1B). To facilitate simulations, only the head groups for each of the seven PIP molecules were used in our docking simulations, with the PIPs truncated at the first carbon atom of glycerol moiety (see Fig. 3B). This results in an inositol phosphate singly methylated at the C1 position, which reduces the charge at the phosphate group and better mimics the PIPs than the inositol phosphate itself. An initial PI(4,5)P2 structure and PDB file were obtained using the PRODRG server, and the structure was constrained such that the hydroxyl group was axial at the second carbon position of the inositol ring. Hydrogen atoms on the inositol ring were merged to the carbon atoms. Six other PIPs were generated by modifying the PI(4,5)P2 molecule using Maestro (Schrödinger, Portland, OR). Atom charges for the PIPs were adopted from those reported (27), with PI(4,5)P2 charges shown in Fig. 3B. Autodock Tool 1.5.4 was used to assign atom type and torsion tree for each ligand (26). PI(3)P, PI(4)P, PI(5)P had 9, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, PI(4,5)P2 had 10, and PI(3,4,5)P3 had 11 rotatable bonds.

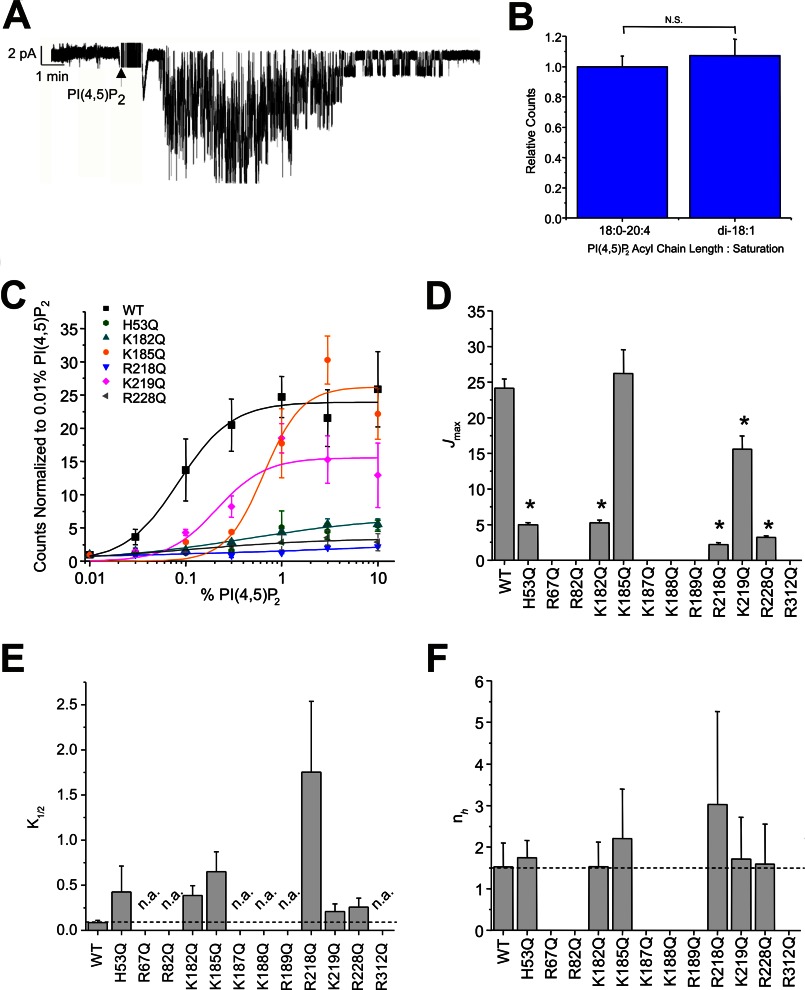

FIGURE 1.

A, superfusion of PI(4,5)P2 onto a patch of membrane containing Kir2.1 channels can recover channel activity after rundown. B, activation of Kir2.1 channels by PI(4,5)P2 is not sensitive to the acyl chain length or saturation as determined by comparing maximal activation between di-18:1 (dioleoyl) and 18:0–24:4 (stearoyl-arachidonoyl) PI(4,5)P2. C, PI(4,5)P2 concentration-activity relationship for WT and mutant Kir2.1 channels. For clarity, only mutants in which some activity could be observed are shown. Solid lines are fit curves using the Hill equation. No discernable activity was detected for R67Q, R82Q, K187Q, K188Q, R189Q, and R312Q Kir2.1 channels even in liposomes containing 30% PI(4,5)P2. D–F, parameters of fits to the Hill equation indicate that K185Q and K219Q mutants primarily shift the K1/2 of PI(4,5)P2, whereas H53Q, K182Q, R218Q, and R228Q mutations reduce the maximal flux as well as increase the K1/2 of PI(4,5)P2. No mutation significantly altered the Hill co-efficient (nH ≈ 1.5) which has been suggested to be a measure of co-operativity between ligands. Error bars, S.D.; N.S., not significant; n.a., no detectable activity.

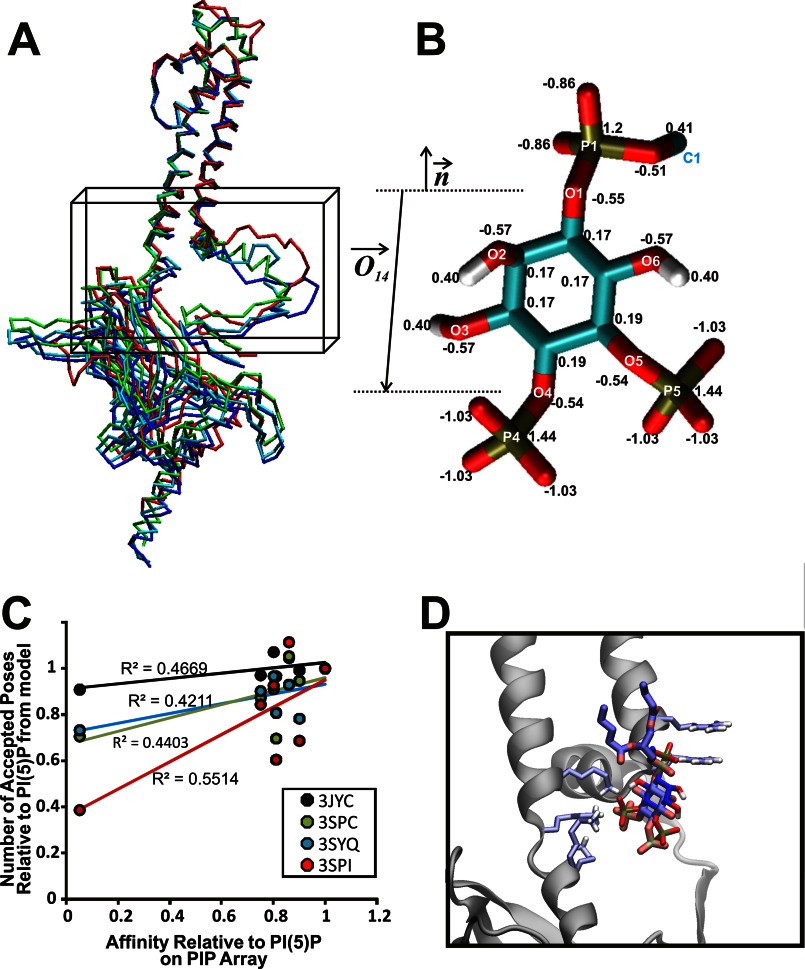

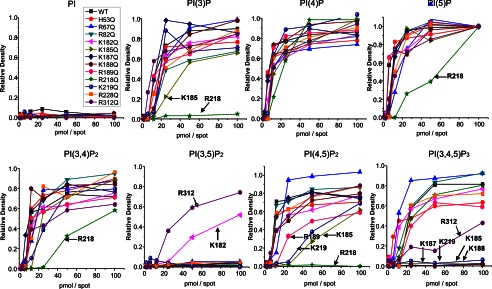

FIGURE 3.

The interaction of individual mutant Kir 2.1 to the PIP Arrays. Mutant Kir2.1 protein bound to the PIP Arrays was probed with an anti-His antibody. The raw images are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. Densitometry measurements from PIP Arrays were internally normalized to density measured for the 100 pmol spot of PI(5)P and are plotted for lipids individually. The mutations that caused >50% reduction in binding compared with WT Kir2.1 are designated by an arrow and residue name. These data indicate that for each PIP, it is a different subset of residues that when mutated to Gln (Q) disrupts channel binding. This suggests that these ligands orient differently in the binding pocket, thereby interacting with different subset of residues, which may explain why they do not equivalently trigger activation in Kir2.1 channels.

Search Space and Grid Map Generation

The grid space for docking simulation was limited to the region into which lipid head groups can reach with the lipid tail still embedded in the membrane. The membrane was not present in the docking simulations, but its potential location with respect to the protein was approximated based on the slide helix position. The searched region fully covered the sliding helix, the lower end of the TM1 helix, the N-terminal β-strand of subunit A and the adjacent part of neighboring subunits B and D, which was necessary to identify potential interactions at the subunit interface as shown in Fig. 4A. The resulting grid space differed slightly between individual models based on different crystal structures. In particular 3JYC, which exhibits a greater displacement of the cytoplasmic domain from the TM domain than other structures, resulted in a wider search space although the structural parts included for the search were almost equivalent. With grid space of ∼0.34 Å, the grid points were 126 × 102 × 100 for 3SPI and 3SYQ, 126 × 104 × 100 for 3SPC, and 126 × 112 × 100 for 3JYC. Grid parameter files were generated using Autodock Tool 1.5.4., and grid maps were generated by AutoGrid 4.2. program.

FIGURE 4.

Docking of various PIPs to wild type Kir2.1 protein models. A, Cα trace of representative homology models of human Kir2.1 based on the chicken Kir2.2 structures (PDB ID codes 3JYC (blue), 3SPC (cyan), or 3SPI (green)) and mouse Kir3.2 (PDB ID code 3SYQ (red)). The search region for autodocking is designated by a black box. B, surrogate structure of the PI(4,5)P2 ligand with atom names and charges. The surrogates are the mimics of the PIPs with acyl chains cut off at the C1 position. Other PIPs were generated through substituting with either a hydroxyl or phosphate group at positions 3, 4, and 5 on the inositol ring. Atom charges are transferable to other PIPs. The vector for molecular axis (O⃗14) and bilayer normal (n⃗) are used for docking simulations and analysis. C, relative affinities (assessed by number of correctly oriented poses) for each ligand from our computational experiments compared with the relative binding affinities determined from the PIP Arrays. R2 values for the linear fit were 0.5514, 0.4669, 0.4403, and 0.4211 for 3SPI, 3JYC, 3SPC, and 3SYQ derived Kir2.1 models, respectively. This analysis suggests that the protein bound to the PIP Arrays most likely resides in a similar conformation to that observed in the closed PI(4,5)P2-bound structure (PDB ID code 3SPI), with weak binding in both cases to PI(3,5)P2, and so the remainder of our analysis was performed on docking simulations to models derived from this structure. D, docked pose of PI(4,5)P2 bound to Kir2.1–3SPI in darker color compared with the crystallographic PI(4,5)P2 bound to Kir2.2 in light color. Chicken Kir2.2 subunit A is shown schematically, and six basic residues in the binding pocket are shown as sticks.

Docking Parameters and Simulations

For each model, 100 independent docking simulations were performed on the 100 homology models for four templates by Autodock 4.2 program using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm (28). All default parameters were used except that the maximum number of evaluations was raised from 2,500,000 to 25,000,000. This ensured that a stable minimum was found in each case. Each docking simulation was run for ∼8 h on a single processor of IBM x3650-m2 nodes for PI(3)P, PI(4)P, PI(5)P, 10 h for PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, PI(4,5)P2, and 11 h for PI(3,4,5)P3.

Acceptance

For each template, 10,000 poses were respectively generated for seven ligands. Poses were accepted based on their orientation. A pose was accepted if the angle between the molecular vector (O⃗14) and bilayer normal (n⃗) (see Fig. 2B) was >90°, which occurred when the head group was either pointing away from the membrane or less than parallel to the membrane surface. Current and following analyses were performed by in-house programs running on MatLab (MathWorks, Natick, MA)

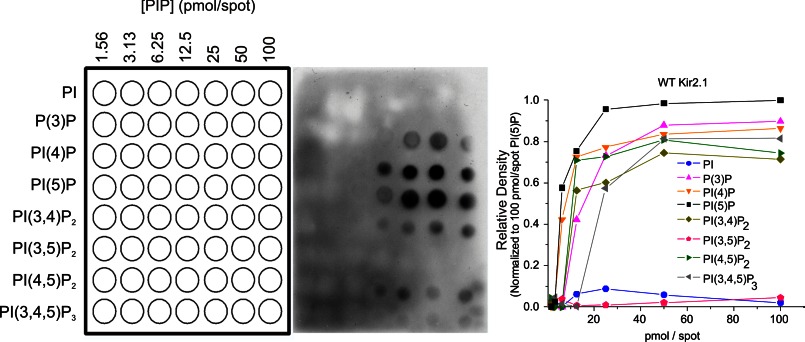

FIGURE 2.

The interaction of wild type Kir2.1 to PIP Arrays. A schematic diagram of PIP Arrays (left) shows an increasing amount of lipids from left to right. PIP Arrays were incubated with WT Kir2.1, and bound proteins were probed with an anti-His antibody (center). Densities in each array were internally normalized to density measured for the 100 pmol spot of PI(5)P (right).

Clustering

To elucidate representative binding sites the accepted poses were clustered into subgroups. A K-mean clustering algorithm was adopted using as a metric the root mean square deviation of distances of the phosphorus atom to an atom (CZ for Arg and NZ for Lys) of putative binding residues (80 (Arg), 82 (Arg), 182 (Lys), 185 (Lys), 187 (Lys), 188 (Lys)) (see Fig. 5A) was used to cluster the accepted poses.

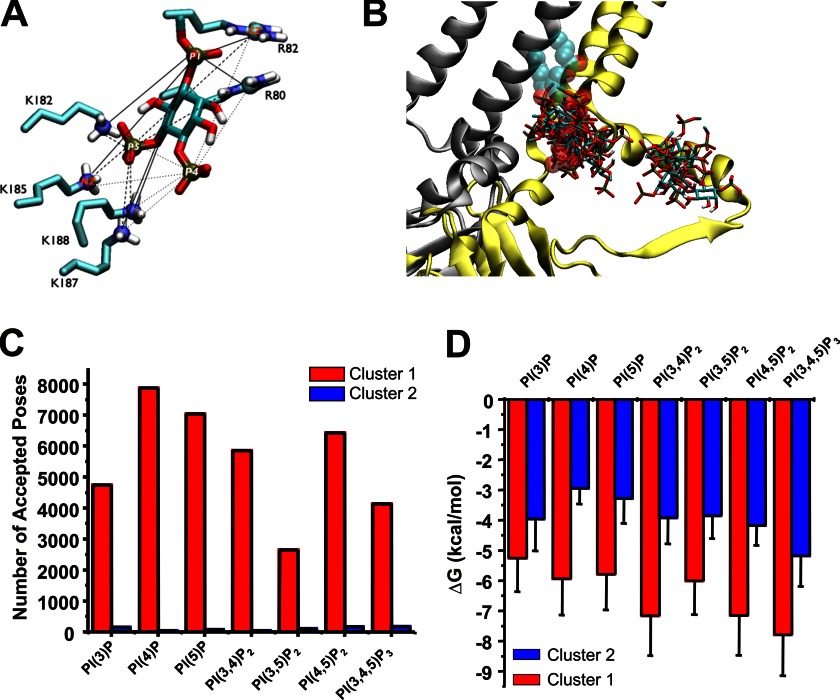

FIGURE 5.

A, distances between a ligand and the six putative binding residues. The pairs between the phosphorus atoms (P1, P4, and P5) of PI(4,5)P2 and the side chain atoms (CZ of Arg80, Arg82 and NZ of Lys182, Lys185, Lys187, and Lys188) are visualized by solid, dashed, and dotted lines. The distances of these pairs were used to cluster accepted poses. B, Kir 2.1–3SPI subunit A and D shown in yellow and silver ribbon, respectively, with the crystallographic PI(4,5)P2 bound to the subunit A shown in sphere translucently. An overlay of a single representative pose from each cluster of seven different C1-PIP ligands stacked on the Kir2.1–3SPI surface clearly indicates that these ligand bind primarily within two clusters. C, number of accepted poses within cluster 1 (red) and cluster 2 (blue) for each PIP. For each PIP, 96–99% of poses reside in cluster 1. D, average binding energy for poses in cluster 1 (red) and cluster 2 (blue) for each PIP docked to Kir2.1–3SPI.

To cluster all accepted poses (N), relative location of a ligand to the protein was used as a metric. The relative position was determined by the distance from each phosphate atom in the ligand to the six putative binding residues. Distances were combined into a vector li{r1, r2, …. rn} where ri is the distance between one phosphorus atom and one side chain atom and n is 6 × p (phosphorus atom number in the ligand).

Matrix M (n× N) consists of distance vector li of all the accepted poses, after clustering M is subgrouped into

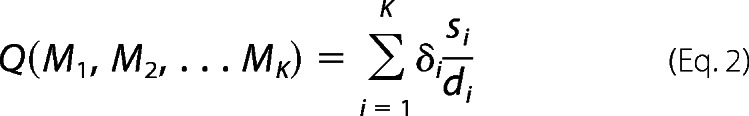

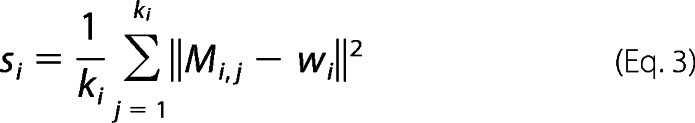

where MK is a submatrix and K is the number of clusters. K-mean clustering is performed according to the following: (i) K poses are randomly assigned as initial centroids {w1,w2,… wK}. (ii) The distance of a pose from these centroids is computed, and the pose is assigned to the closest centroid. (iii) After assignment is made for all poses, new centroids are computed from the members belonging to each centroid and (iv) tested for change from the previous centroids. (v) If centroid is different, steps 2 through 5 are repeated until centroids do not change. (vi) If the new centroids and previous centroids are the same, the clustering is accomplished, and the cluster indices of each pose are stored and performance index is computed according to Equation 2 (29)

|

where δi and si are relative weights and a mean intracluster variance of the ith subgroup respectively, and di is the minimum distance of ith subgroup to one of all other clusters that accounts for intercluster variance. δi, di, and si are computed as follows

|

where ki is the number of poses and wi is the centroid of the ith cluster.

|

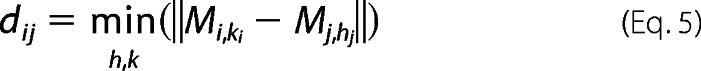

where

|

where dij is the shortest distance among all the possible pairs between the members of Mi and Mj, and the smallest dij is finally determined di of ith cluster.

|

where ki is the number of poses in the ith subgroup and N is the number of accepted poses. The best clustering was determined by the minimum Q value.

The number of clusters for each ligand was determined to minimize the performance index (Q). The smaller the Q value, the greater the intersubgroup variance and the smaller the intrasubgroup variance, which indicates better clustering performance. Five clustering trials on the accepted poses for each ligand were performed, and the trace of a trial with the minimum Q value at any cluster number was chosen and is shown in Fig. 6A. Two clusters (cluster 1 for the larger and cluster 2 for the smaller cluster) were identified. The poses in cluster 1 were subgrouped for each ligand to identify major conformations of bound ligands.

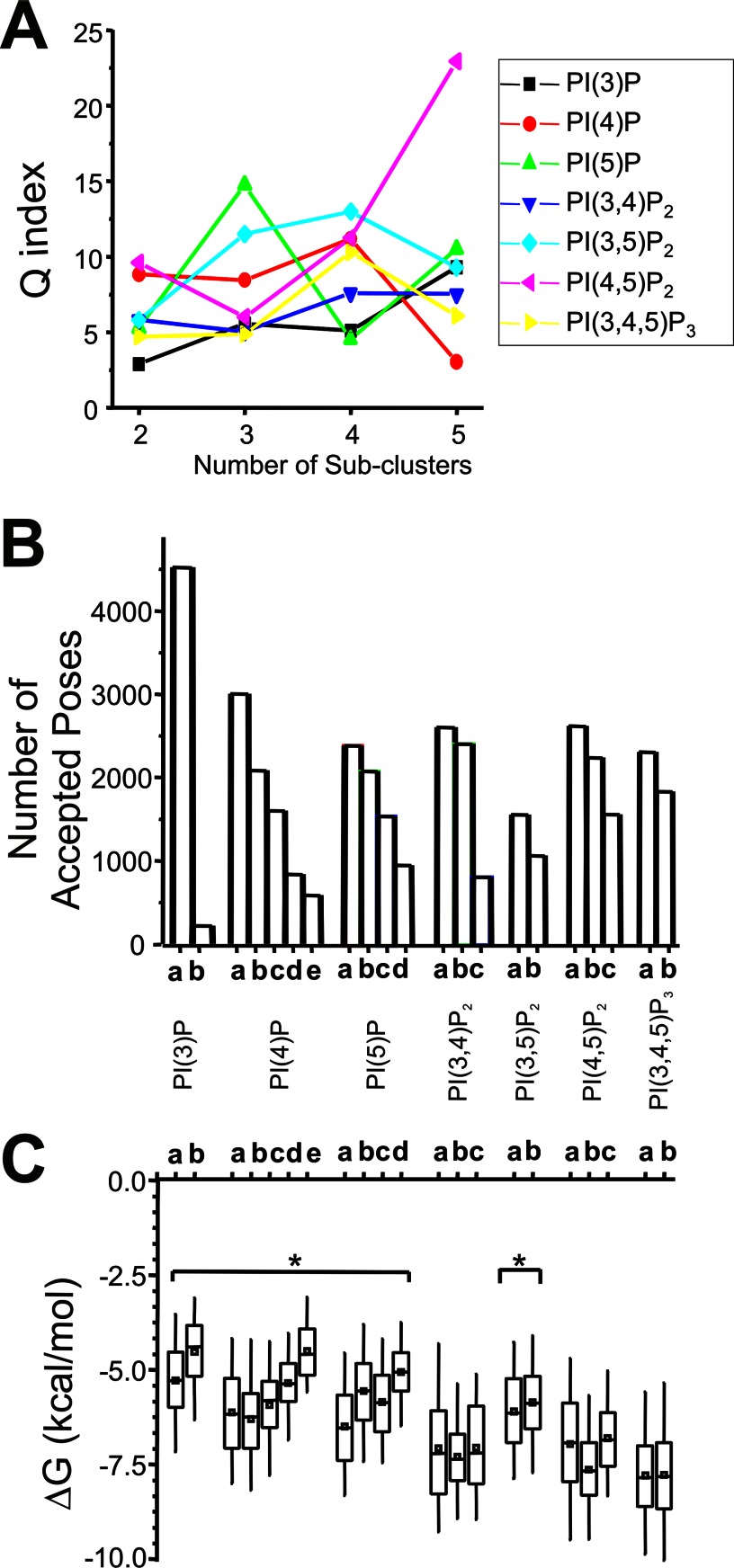

FIGURE 6.

A, the minimum value determined from the performance index (Q) versus cluster number taken to determine the optimal number of subclusters for PIP binding in cluster 1. B, the number of accepted poses in each subcluster for each of the seven PIP ligands docked to Kir2.1–3SPI. C, box-whisker plot of binding free energy (ΔGbinding in kcal/mol) within a subcluster for each PIP ligand. Monophosphorylated PIPs and PI(3,5)P2 bind with higher average energies than PI(4,5)P2; however, selective activation of Kir2.1 channels by PI(4,5)P2 cannot be solely accounted for based on this because PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 bind with similar energies.

Contact Analysis

To visualize the clustering results based on the multidimensional variables, contact patterns between the ligand and frequently contacting residues were determined. Hydrogen bonds were defined by two criteria: (1) the distance between the donor and acceptor atoms being shorter than or equal to 3.4 Å, and the angular orientation being smaller than or equal to 30° between the two unit vectors. One joins hydrogen bond donor atom and hydrogen atom and the other joins hydrogen bond donor and acceptor atoms.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t test or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc analysis as appropriate, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of Kir2.1 Residues that Control PIP Binding

Kir2.1 channels show an absolute requirement for the phosphoinositide PI(4,5)P2 for channel activity (2). PI(4,5)P2 can be superfused onto the inner leaflet of an excised patch of membrane containing purified Kir2.1 channels and restimulate channel activity following rundown, in the absence of any other proteins or intracellular signaling pathways (Fig. 1A). Maximal reconstituted Kir2.1 channel activities measured by 86Rb+ uptake into proteoliposomes containing di-18:1 (dioleoyl) or 18:0–24:4 (stearoyl-arachidonoyl) PI(4,5)P2 were indistinguishable (Fig. 1B), indicating that the length and degree of saturation in the acyl chain are not major determinants of channel activity and reflect similar conclusions drawn from patching channels in mammalian cells (13). We also showed previously that Kir2.1 are very specifically activated by PI(4,5)P2, with only ∼10% of maximal activity by PI(3,4,5)P3 and little or no activation by the remaining PIPs (2). Furthermore, in the presence of high concentrations of anionic phospholipids such as phosphatidylglycerol, other PIPs can competitively inhibit PI(4,5)P2-dependent channel activity (5). This suggests that the various PIPs may bind to the same general location in Kir2.1 channels, but does not explain why they do not equivalently trigger channel activation. To address this, we have examined the effects of mutations of positively charged residues on the cytoplasmic side of Kir2.1 channels on PIP-driven channel activation in the absence of other proteins or intracellular pathways and then the effects of these mutations on PIP binding directly.

Twelve positively charged residues on the cytoplasmic side of the channel have been previously shown to alter Kir2.1 channel sensitivity to activation by PI(4,5)P2 (7, 12–16). Similar mutational effects have been identified in other Kir channels (10, 12, 15, 17, 30–39). We quantified the PI(4,5)P2 dependence of wild type and mutant channel activation directly and independently of other proteins or downstream signaling pathways in liposomes of defined composition using the 86Rb+ uptake assay (Fig. 1C). K185Q and K219Q mutations primarily shifted the K1/2 of activation (Fig. 1E), whereas H53Q, K182Q, R218Q, and R228Q mutations reduced the maximal flux (Fig. 1D) as well as the K1/2 of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 1E). There was no discernable activity of R67Q, R82Q, K187Q, K188Q, R189Q, and R312Q mutant channels, even in liposomes containing 30% PI(4,5)P2. Interestingly, none of the mutations caused any obvious change in the Hill co-efficient compared with WT (nH ≈ 1.5; Fig. 1F) suggesting that stoichiometry or co-operativity of PI(4,5)P2 activation is unaffected by these mutations. The results are generally consistent with the effects of these mutations on Kir2.1 currents in recombinant cells (12). Thus, each of these mutations directly affects the sensitivity of Kir2.1 channels to activation by PI(4,5)P2., although the above analyses cannot determine whether any particular mutation does so through disruption of ligand binding or by affecting transduction to channel opening.

To assess channel-PIP binding affinity directly, we made use of a biochemical lipid binding assay (PIP Arrays), as has previously been employed to assess PIP binding sites in the C terminus of KCNQ1 channels (40). WT Kir2.1 channels, detected with anti-His antibody, bound to PIP Arrays with a characteristic pattern (Fig. 2). Kir2.1 showed the highest binding to PI(4)P and PI(5)P with only modest binding to PI(4,5)P2, PI(3)P, PI(3,4)P2, and PI(3,4,5)P3 and with no observable affinity to PI and PI(3,5)P2. This characteristic binding pattern suggests that higher binding affinity is not the determinant of PI(4,5)P2 specificity.

To ensure that the binding pattern on PIP Arrays was not due to protein aggregation in the buffer used, two experiments were performed. First, purified protein from the peak fractions that corresponded to the size of Kir2.1 tetramers and used for both functional studies and the binding assay (supplemental Fig. S1A) was incubated overnight in Tween 20 detergent and re-run on a gel filtration column in TBK-T buffer. Kir2.1 protein maintained its tetrameric assembly in TBK-T (supplemental Fig. S1B). Additionally, purified Kir2.1 that was purposely aggregated by heating to 95 °C showed no evidence of binding to the PIP Array (supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that (i) any binding of aggregated protein to the array will not be detected by the anti-His probe, and (ii) there is no nonspecific binding of the anti-His probe to the array. Together, these data indicate that the pattern we observed resulted from binding of correctly folded tetrameric protein and that changes in the binding pattern observed in the following experiments reflect disrupted binding due to the specific mutation.

H53Q, R67Q, R82Q, K182Q, and K228Q mutations did not markedly affect the binding of any of the PIPs (although PI(3,5)P2 binding was slightly enhanced with the K182Q mutation) (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S2 for the raw images of PIP Array). Thus, although these residues may interact with bound PIP, their role in regulating channel activity appears to be primarily in transduction through the downstream gating mechanism. On the other hand, Lys185, Lys187, Lys188, Arg189, Arg218, Arg219 and Arg312 all markedly affected the binding of various PIPs (Fig. 3), and interestingly, binding of each PIP isoform appears to be regulated by a different subset of key residues (Table 1). For example, PI(4,5)P2 binding appears to be controlled by Lys185, Arg189, Arg218, and Lys219, with R218Q abolishing binding in the range of the array. On the other hand, PI(3,4,5)P3 binding was disrupted by mutations of Lys185, Lys187, Lys188, Lys219, and Arg312, whereas PI(5)P and PI(3,4)P2 binding was only disrupted when Arg218 was mutated to glutamine. Estimates of ΔΔG of PIP binding between WT and these various mutants are shown in Table 1. These data imply that the key interactions which govern binding of each particular PIP are different, which may help explain why PIPs other than PI(4,5)P2 fail to stimulate channel activation. Notably, none of the N-terminal residues tested (His53, Arg67, and Arg82) disrupted PIP binding when mutated, suggesting that the N terminus primarily plays a role in regulating channel gating transitions rather than controlling PIP binding itself.

TABLE 1.

ΔΔG (in kcal/mol) of PIP binding between WT and Gln mutant Kir2.1 channels from PIP Arrays

| Ligand | Lys185 | Lys187 | Lys188 | Arg189 | Arg218 | Lys219 | Arg312 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI(3)P | 0.45 | 1.11 | |||||

| PI(5)P | 1.24 | ||||||

| PI(4,5)P2 | 0.89 | 0.44 | 1.24 | 0.85 | |||

| PI(3,4,5)P3 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

Arg189 is a particularly notable residue, because mutation to glutamine only slightly reduced channel binding to PI(4,5)P2 and had no effect on binding of other PIPs (Fig. 3), even though it completely abolished channel activity (Fig. 2). This residue may thus serve as a lynch-pin, coupling PI(4,5)P2 binding to a transduction mechanism that leads to channel activation.

Ligand Docking of Various PIPs to Human Kir2.1

As noted, Kir2.1 channels are uniquely activated by PI(4,5)P2, with only weak activation by PI(3,4,5)P3 and little or no activation by the remaining PIPs (2). Biochemical assessment of binding (Figs. 2 and 3) suggests that this selectivity does not arise from the specificity of PIP binding because PI(4)P and PI(5)P bind at least as well as PI(4,5)P2 and suggests instead that differences in the nature of the binding, or of the coupling to channel opening, are key. To gain further insight to how the various PIPs interact with Kir2.1 channels and why these channels cannot be activated by all PIP isoforms, we turned to computational ligand docking experiments. We built homology models of human Kir2.1 (Fig. 4A) based on the recently solved chicken Kir2.2 (PDB ID codes 3JYC, 3SPC, 3SPI) (9, 19) and mouse Kir3.2 (PDB ID code 3SYQ) structures (41) and docked different PIPs to the model structures thus generated. Loops that were not resolved in the structure were added through a loop sampling module implemented in Modeler. To overcome the limited number of rotatable bonds allowed in Autodock 4.2, side chain flexibility was accounted for by generating 100 models for each of these templates, thus enabling “pseudo-flexible” docking simulations. Because the length and saturation of the acyl chain were not critical for channel activation (Fig. 1B) we used only the headgroups of the PIP ligands (Fig. 4B) in our computational docking experiments. However, to minimize the bias that may be introduced by using just the headgroups, the acyl chains of the PIP ligands were removed from the P1 phosphate at C1 (C1_tail) (Fig. 4B, see “Experimental Procedures”). Docking poses were analyzed for correct orientation, with poses in which the “tails” were oriented facing away from the expected plane of the membrane removed. In our docking simulations, the membrane was not present. The relative affinities for the various PIPs (assessed by the number of correctly oriented poses in our computational experiments) were compared with the relative binding affinities determined from the PIP Arrays for each group of models (Fig. 4C). The closest agreement between model and experiment suggests that, when bound to the PIP Arrays, the WT protein resides in a similar conformation to the closed PI(4,5)P2 bound Kir2.2 structure (PDB ID code 3SPI). Additional docking simulations were therefore performed on models of Kir2.1 derived from this structure (hereby denoted as Kir2.1–3SPI models). As an internal control, we first ensured that docking simulations in the Kir2.1 models could recapitulate PI(4,5)P2 binding in a position and orientation similar to those observed in the PI(4,5)P2-bound Kir2.2 structure (Fig. 4D). Accepted poses were clustered using the relative distance of all phosphorus atoms in the ligand to the six putative binding residues (Fig. 5A), which demonstrated two regions near the cytoplasmic domain-membrane interface to which all of the seven PIP ligands bound (Fig. 5B). A summary of the number of accepted poses in each region (clusters 1 and 2) for the various PIPs is presented in Fig. 5C. Cluster 1 reflects the location of the bound PI(4,5)P2 in the Kir channel crystal structures, and 96–99% of accepted poses reside in this cluster (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the average binding energy determined by Autodock4.2 is significantly lower in cluster 1 than in cluster 2, for all PIPs (Fig. 4D). We speculate that cluster 2 may reflect the secondary anionic phospholipid site that we described previously (5). A recent simulation also predicted the end of slide helix as a putative anionic lipids binding site (42). However, further in-depth computational analysis and direct experimentation are required to test this idea.

We examined the interaction of the PIP ligands within cluster 1 in further detail. Poses in cluster 1 were subclustered with the number of subclusters (two to five) for each ligand being determined by the minimized performance index value (Q) (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S3). The number of poses in each subcluster is shown in Fig. 6B. The free energy of binding (ΔGbinding) estimated from the docking simulations (Fig. 6C) is significantly higher for all monophosphorylated PIPs than for di- or triphosphorylated PIPs. This appears contrary to the observation of stronger binding of monophosphorylated, particularly PI(4)P and PI(5)P in the PIP Arrays. However, subclustering indicates that both PI(4)P and PI(5)P dock with a wider range of orientations than PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 6), suggesting that preferential binding to these monophosphorylated PIPs observed in the array may be entropically driven. Additionally, it is noticeable that the phosphoinositides that contain a 3′ phosphate show significantly fewer acceptable poses than other PIPs (Figs. 5C and 6B). This appears to result from a steric clash that arises between the 2′ hydroxyl group that is axial to the inositol ring and residue Trp81 side chain if these ligands were to dock in positions similar to PI(4,5)P2. As a result, these 3′ phosphorylated ligands bind more shallowly within the pocket, with fewer stabilizing interactions with channel side chains and therefore with weaker binding affinity (Figs. 5D and 6C). Assuming that the orientation of PI(4,5)P2 in the recent crystal structure of Kir2.2 (19) is the one that underlies the activation of the channel, then the present docking experiments provide a clear explanation why the other PIPs do not activate the channel, because they cannot coordinate the same group of side chains with the same bonding interactions. Interestingly, PI(3,4,5)P3, the only other ligand that marginally activates the channel (2, 13), can co-ordinate with the appropriate side chains in a manner similar to PI(4,5)P2 (PI(3,4,5)P3 cluster 1b (supplemental Fig. S3) and with similar energies (Fig. 6C), although this pose is observed with much lower frequency (Fig. 6C) than it is with PI(4,5)P2.

Ligand Docking of Various PIPs to Mutant Human Kir2.1

To assess the effect of individual residues on the binding of various PIPs to the Kir2.1 proteins, docking simulations were repeated on mutant channels. Mutations of residues located away from cluster 1 (namely Arg189, Arg218, Lys219, and Arg312) were excluded due to the inability to capture conformational changes that might result from mutation of these residues. The six remaining basic residues (Arg80, Arg82, Lys182, Lys185, Lys187, and Lys188) that form cluster 1 were mutated into Gln individually, with the results of these docking simulations summarized in Fig. 7.

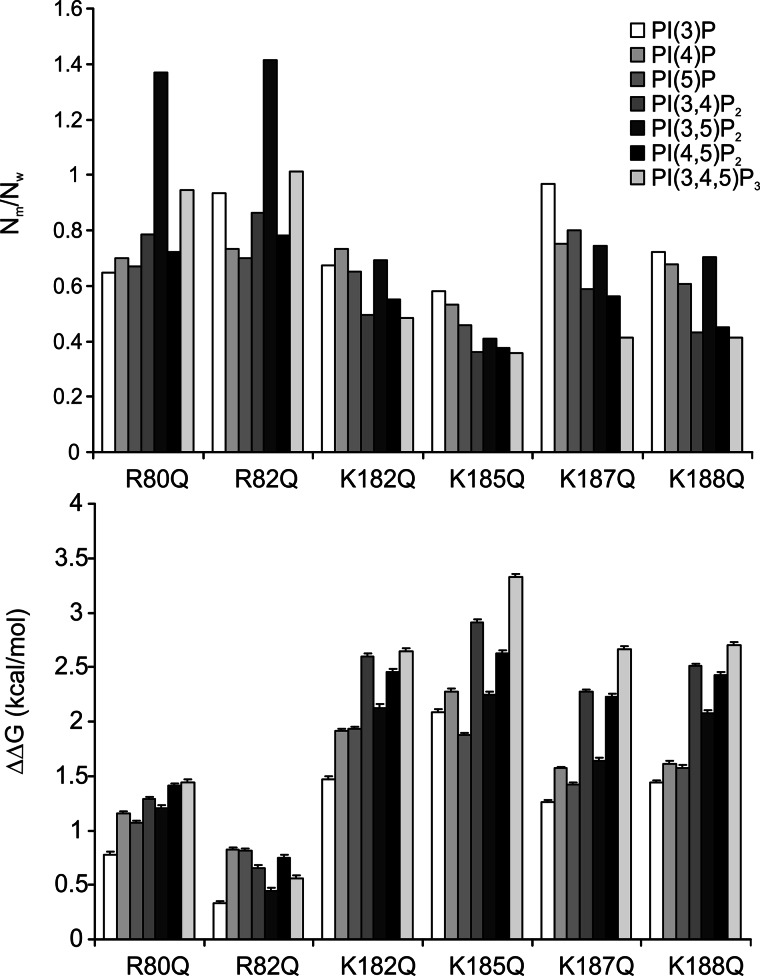

FIGURE 7.

Docking of various PIPs to Kir2.1 mutant protein models. The same docking simulations were carried out on the Kir2.1 model proteins with a single mutation as listed in this figure. Top, the number of accepted poses in cluster 1 relative to that of wild type protein is shown. Bottom, the difference of binding free energy in the cluster 1 between the wild type and each mutant protein is shown in kcal/mol unit. Error bars represent S.E.

The number of accepted poses of each PIP in cluster 1 is shown as a ratio of the accepted poses in the previous simulations to the wild type protein. Except for PI(3,5)P2, docking to R80Q and R82Q mutant proteins, the number of accepted poses was lower for all mutants than for wild type protein. All of the mutations increased the binding energy for all PIPs. Among the six mutations, K185Q resulted in the greatest attenuating effect on PIP binding to cluster 1. Polyphosphorylated PIPs were more susceptible to mutations than monophosphorylated PIPs. These docking results qualitatively match the PIP Array data in the two following aspects: no single mutation in the binding pocket abolishes binding, and the K185Q mutation had the greatest effect on PIP binding.

Mechanism of PIP Activation of Kir2.1

Both our biochemical and computational analyses indicate that PI(4,5)P2-specific activation arises not from a uniquely low free binding energy for this ligand. Instead, multiple PIP ligands bind with varying energies in the same overall location (cluster 1), but nonidentical conformations, implying that the appropriate structural changes that lead to channel activation are specific to the preferred PI(4,5)P2 conformation. Only PI(3,4,5)P3, which binds to this site with similar energy to PI(4,5)P2, occasionally samples a very similar conformation. Monophosphorylated PIPs interact in the same binding pocket with lower affinity, but greater conformational freedom, which may lead to entropically driven competitive inhibition.

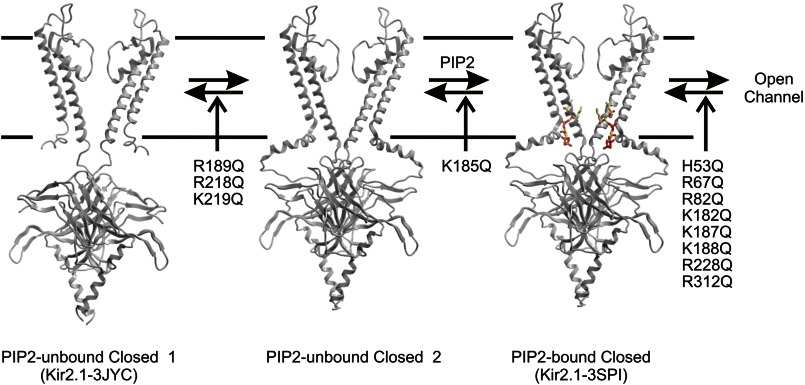

Kir2 channels are constitutively closed in the absence of PI(4,5)P2, and increased PI(4,5)P2 reduces Kir2.1 channel closed times (14, 43), suggesting that the predominant pathway to channel activation may be PI(4,5)P2 binding to a closed state, followed by channel opening (Fig. 8). Multiple mutations affect the process of PI(4,5)P2 activation (12, 44), and using a combination of biochemical and computational approaches, we can identify mutations that affect binding of phosphoinositides separately from mutations that primarily act to alter channel gating by shifting the relative stability of the open state. Only a relatively small subset of those mutations that significantly alter channel activation actually interfere with ligand binding (Fig. 8). Of these, K185Q identifies a PI(4,5)P2-interacting residue in the Kir2.2 crystal structure. Thus, residues Arg189, Arg218, and Lys219, which are located some distance from the crystal structure binding site and from the identified sites in the docking analysis may be influencing binding indirectly, potentially by disruption of the extensive hydrogen bonding network that links the cytoplasmic domain of one subunit to the slide helix of the neighboring subunit (19, 41). Disruption of such a network could transition to a structure resembling the 3JYC Kir2.2 structure (PI(4,5)P2-unbound closed 1; Fig. 8), thereby disrupting PIP binding due to a loss of the three-dimensional conformation needed to co-ordinate these ligands. This is supported by the fact that the binding energy of all ligands to 3JYC models was increased by ∼3 kcal/mol. Recent FRET studies indicate that extensive co-ordinated rearrangements of the Kir cytoplasmic domain occur during PI(4,5)P2 gating (21). Residues Arg82, Lys182, Lys187, and Lys188 all interact with the PI(4,5)P2 in the 3SPI structure, yet mutation of these residues (together with multiple other mutations that inhibit activation, including H53Q, R67Q, R228Q, and R312Q) do not significantly disrupt PI(4,5)P2 binding, indicating that loss of any one interacting residue does not abolish binding. Instead, we suggest that the primary effect of these mutations may be disruption of the necessary gating transitions that lead to channel opening following PI(4,5)P2 binding (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Proposed model for the predominant pathway to channel activation. Kir2.1 channels may undergo a conformational change in which the cytoplasmic domain moves from a 3JYC type closed conformation (1) toward the plasma membrane and interacts through a hydrogen bond network with the slide helix, leading to a PI(4,5)P2 unbound structure (similar to what was observed for the Kir3.2 apo structure). We suggest that this transition may be less favored by mutations R189Q, R218Q, and K219Q, leading to reduced binding of PIP ligands. However, once the transition occurs, this state generates a three-dimensional binding pocket that strongly co-ordinates PI(4,5)P2, binding of which is disrupted by K185Q mutation. Further conformational changes lead to channel opening. Multiple mutations disrupt this transition, without affecting earlier steps of binding.

Mutations in Kir2.1 channels cause cardiac arrhythmias, periodic paralysis, and developmental phenotypes of Andersen-Tawil syndrome (16, 44). Many disease mutations, including R67W, R189I, R218W/Q, R312C, have been suggested to disrupt PI(4,5)P2 binding (16), although this has not been confirmed by biochemical binding assays. Our data indicate that mutations of residues Arg189 and Arg218 do indeed disrupt PI(4,5)P2 binding, although mutations of Arg67 and Arg312 do not. Pegan et al. (8) observed stable tetramers for WT cytoplasmic domain-only constructs, but not for 218Q mutants. They thus suggested that this mutation might lead to disruption of the channel assembly. However, full-length R218Q constructs remain tetrameric in solution (supplemental Fig. S1A) and retain very low but still observable activity (Fig. 1C). Thus, it is unlikely that the disease mechanism of mutation R218Q is through a misfolded cytoplasmic domain, but rather through disruption of PI(4,5)P2 binding. Distinct modes of action of various Andersen-Tawil mutations should be considered during efforts to develop therapeutic treatments for diseases involving Kir2 channels.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a combination of biochemical and computational approaches, we have determined the role of charged residues in the cytoplasmic domain in PIP activation of Kir2.1 channels. We determine residues that are critical for binding of phosphoinositides and residues that primarily act to alter channel gating. The data indicate that PI(4,5)P2-specific activation arises not from uniquely low free binding energy for this ligand and instead suggest that interactions in a specific conformation trigger appropriate changes that lead to channel activation. Only PI(3,4,5)P3, which binds to this site with similar energy, may occasionally sample a similar conformation. Monophosphorylated PIPs may interact in the same binding pocket with greater conformational freedom, thereby leading to entropically driven competitive inhibition.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Oscar Harari for useful discussion regarding clustering analysis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL54171 (to C. G. N.) and K99 HL112300-01 (to N. D.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Fellowship 13POST14660069 (to S. J. L.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- Kir channel

- inward rectifier potassium channel

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- PIP

- phosphoinositide

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphoinositide 4,5-bisphosphate

- PI(3,4,5)P3

- phosphoinositide 3,4,5-trisphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cheng W. W., Enkvetchakul D., Nichols C. G. (2009) KirBac1.1: it's an inward rectifying potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 295–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D'Avanzo N., Cheng W. W., Doyle D. A., Nichols C. G. (2010) Direct and specific activation of human inward rectifier K+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37129–37132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Enkvetchakul D., Jeliazkova I., Nichols C. G. (2005) Direct modulation of Kir channel gating by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35785–35788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leal-Pinto E., Gómez-Llorente Y., Sundaram S., Tang Q. Y., Ivanova-Nikolova T., Mahajan R., Baki L., Zhang Z., Chavez J., Ubarretxena-Belandia I., Logothetis D. E. (2010) Gating of a G protein-sensitive mammalian Kir3.1 prokaryotic Kir channel chimera in planar lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39790–39800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng W. W., D'Avanzo N., Doyle D. A., Nichols C. G. (2011) Dual-mode phospholipid regulation of human inward rectifying potassium channels. Biophys. J. 100, 620–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nishida M., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2007) Crystal structure of a Kir3.1-prokaryotic Kir channel chimera. EMBO J. 26, 4005–4015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pegan S., Arrabit C., Slesinger P. A., Choe S. (2006) Andersen's syndrome mutation effects on the structure and assembly of the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1. Biochemistry 45, 8599–8606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pegan S., Arrabit C., Zhou W., Kwiatkowski W., Collins A., Slesinger P. A., Choe S. (2005) Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 show sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tao X., Avalos J. L., Chen J., MacKinnon R. (2009) Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 Å resolution. Science 326, 1668–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haider S., Tarasov A. I., Craig T. J., Sansom M. S., Ashcroft F. M. (2007) Identification of the PIP2-binding site on Kir6.2 by molecular modelling and functional analysis. EMBO J. 26, 3749–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rohács T., Lopes C. M., Jin T., Ramdya P. P., Molnár Z., Logothetis D. E. (2003) Specificity of activation by phosphoinositides determines lipid regulation of Kir channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 745–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lopes C. M., Zhang H., Rohacs T., Jin T., Yang J., Logothetis D. E. (2002) Alterations in conserved Kir channel-PIP2 interactions underlie channelopathies. Neuron 34, 933–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rohács T., Chen J., Prestwich G. D., Logothetis D. E. (1999) Distinct specificities of inwardly rectifying K+ channels for phosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36065–36072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xie L. H., John S. A., Ribalet B., Weiss J. N. (2008) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) regulation of strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels: multilevel positive cooperativity. J. Physiol. 586, 1833–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang H., He C., Yan X., Mirshahi T., Logothetis D. E. (1999) Activation of inwardly rectifying K+ channels by distinct PtdIns(4,5)P2 interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Donaldson M. R., Jensen J. L., Tristani-Firouzi M., Tawil R., Bendahhou S., Suarez W. A., Cobo A. M., Poza J. J., Behr E., Wagstaff J., Szepetowski P., Pereira S., Mozaffar T., Escolar D. M., Fu Y. H., Ptácek L. J. (2003) PIP2 binding residues of Kir2.1 are common targets of mutations causing Andersen syndrome. Neurology 60, 1811–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang C. L., Feng S., Hilgemann D. W. (1998) Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature 391, 803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soom M., Schönherr R., Kubo Y., Kirsch C., Klinger R., Heinemann S. H. (2001) Multiple PIP2 binding sites in Kir2.1 inwardly rectifying potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 490, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen S. B., Tao X., MacKinnon R. (2011) Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477, 495–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. D'Avanzo N., Cheng W. W., Xia X., Dong L., Savitsky P., Nichols C. G., Doyle D. A. (2010) Expression and purification of recombinant human inward rectifier K+ (KCNJ) channels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr. Purif. 71, 115–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang S., Lee S. J., Heyman S., Enkvetchakul D., Nichols C. G. (2012) Structural rearrangements underlying ligand-gating in Kir channels. Nat. Commun. 3, 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lederer W. J., Nichols C. G. (1989) Nucleotide modulation of the activity of rat heart ATP-sensitive K+ channels in isolated membrane patches. J. Physiol. 419, 193–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas A. M., Tinker A. (2008) Determination of phosphoinositide binding to K+ channel subunits using a protein-lipid overlay assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 491, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eswar N., Marti-Renom M. A., Webb B., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M., Pieper U., Sali A. (2006) in Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, pp. 5.6.1–5.6.3, John Wiley & Sons, New York: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martí-Renom M. A., Stuart A. C., Fiser A., Sánchez R., Melo F., Sali A. (2000) Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 291–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sanner M. F. (1999) Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17, 57–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lupyan D., Mezei M., Logothetis D. E., Osman R. (2010) A molecular dynamics investigation of lipid bilayer perturbation by PIP2. Biophys. J. 98, 240–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morris G. M., Goodsell D. S., Halliday R. S., Huey R., Hart W. E., Belew R. K., Olson A. J. (1998) Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19, 1639–1662 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Savaresi S. M., Boley D. L., Bittanti S., Gazzaniga G. (2002) Cluster selection in divisive clustering algorithms. Proceedings of the 2nd SIAM 1401, 299–314 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fan Z., Makielski J. C. (1997) Anionic phospholipids activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5388–5395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Inanobe A., Nakagawa A., Matsuura T., Kurachi Y. (2010) A structural determinant for the control of PIP2 sensitivity in G protein-gated inward rectifier K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38517–38523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leung Y. M., Zeng W. Z., Liou H. H., Solaro C. R., Huang C. L. (2000) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and intracellular pH regulate the ROMK1 potassium channel via separate but interrelated mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10182–10189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liou H. H., Zhou S. S., Huang C. L. (1999) Regulation of ROMK1 channel by protein kinase A via a phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5820–5825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schulze D., Krauter T., Fritzenschaft H., Soom M., Baukrowitz T. (2003) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) modulation of ATP and pH sensitivity in Kir channels: a tale of an active and a silent PIP2 site in the N terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10500–10505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shyng S. L., Cukras C. A., Harwood J., Nichols C. G. (2000) Structural determinants of PIP2 regulation of inward rectifier KATP channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 116, 599–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shyng S. L., Nichols C. G. (1998) Membrane phospholipid control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science 282, 1138–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stansfeld P. J., Hopkinson R., Ashcroft F. M., Sansom M. S. (2009) PIP2-binding site in Kir channels: definition by multiscale biomolecular simulations. Biochemistry 48, 10926–10933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zeng W. Z., Liou H. H., Krishna U. M., Falck J. R., Huang C. L. (2002) Structural determinants and specificities for ROMK1-phosphoinositide interaction. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282, F826–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cukras C. A., Jeliazkova I., Nichols C. G. (2002) The role of NH2-terminal positive charges in the activity of inward rectifier KATP channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 437–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thomas A. M., Harmer S. C., Khambra T., Tinker A. (2011) Characterization of a binding site for anionic phospholipids on KCNQ1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2088–2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Whorton M. R., MacKinnon R. (2011) Crystal structure of the mammalian GIRK2 K+ channel and gating regulation by G proteins, PIP2, and sodium. Cell 147, 199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmidt M. R., Stansfeld P. J., Tucker S. J., Sansom M. S. (2013) Simulation-based prediction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding to an ion channel. Biochemistry 52, 279–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jin T., Sui J. L., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Chan K. W., Jan L. Y., Logothetis D. E. (2008) Stoichiometry of Kir channels with phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate. Channels 2, 19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Plaster N. M., Tawil R., Tristani-Firouzi M., Canún S., Bendahhou S., Tsunoda A., Donaldson M. R., Iannaccone S. T., Brunt E., Barohn R., Clark J., Deymeer F., George A. L., Jr., Fish F. A., Hahn A., Nitu A., Ozdemir C., Serdaroglu P., Subramony S. H., Wolfe G., Fu Y. H., Ptácek L. J. (2001) Mutations in Kir2.1 cause the developmental and episodic electrical phenotypes of Andersen's syndrome. Cell 105, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. D′Avanzo N., Hyrc K., Enkvetchakul D., Covey D. F., Nichols C. G. (2011) Enantioselective protein-sterol interactions mediate regulation of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic inward rectifier K+ channels by cholesterol. PLoS One 6, e19393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]