Letter to the Editor

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukemia and is currently incurable outside of stem cell transplantation. Chromosomal abnormalities are common in CLL, with up to 80% of patients possessing abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis.(1) The acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities is also common, and the presence of complex karyotype (≥3 cytogenetic abnormalities) is associated with an adverse prognosis,(2-4) as are specific abnormalities. Deletion of 17p13.1, which results in loss of TP53, and 11q22.3 which results in loss of ATM, are found in 10% and 15-20% of patients respectively. Both are associated with aggressive disease and shortened survival.(1, 5-9) TP53 gene mutations have also been shown to be associated with accelerated disease course,(8) poor response to therapy,(10) and shortened survival.(10, 11) Thus, therapies that are effective in patients with high risk abnormalities represent a priority.

The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor flavopiridol is effective in patients with relapsed and refractory CLL, including those refractory to fludarabine. In the initial phase I studies using an active dosing schedule of flavopiridol, approximately 40% of patients responded, including patients with genetically high-risk disease.(12) In a subsequent phase II trial, over 50% of heavily pretreated patients responded.(13) These two trials, OSU 0055 and OSU 0491, now have longer follow-up (median 2.8 years), and herein we examine the contribution of interphase cytogenetic abnormalities, complex karyotype, and TP53 abnormalities to response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

FISH was performed to detect ATM and TP53, as well as the chromosome 12 centromere and D13S319 located at 13q14.3. Dohner’s hierarchical classification was used to form three groups of patients: those with del(17p13.1), those with del(11q22.3) and those with other cytogenetic abnormalities or normal cytogenetics. Stimulated metaphase cytogenetics were performed to determine complexity; a complex karyotype was defined as ≥3 unrelated abnormalities. Coding TP53 exons were analyzed using PCR amplification with primers designed to cover the entire exon and adjacent fragments of introns to include splicing donor and acceptor sites. Specimens with good quality amplicons were subsequently heteroduplexed with the exon matching control DNA and analyzed using temperature gradient capillary electrophoresis (TGCE), the methods for which have been validated by our group. Estimates of PFS and OS were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to compare differences among survival curves. The proportional hazards model was used to model both PFS and OS as a function of cytogenetic group and presence of complex cytogenetics, controlling for age, Rai stage, bulky lymphadenopathy, number of prior treatments, and treatment/dose schedule. The logistic regression model was used to model overall response rates (ORR) as a function of the variables listed above. Statistical significance was set at α=0.05. 112 patients are included in this analysis. Using Dohner’s hierarchical classification, 40 patients (36%) had del(17p13.1), 37 (33%) had del(11q22.3), and 35 (31%) had neither of these abnormalities. These groups were not significantly different in terms of age, sex, Rai stage, or percent fludarabine-refractory. The median number of prior treatments was 4 (range 1-11) and did not differ among cytogenetic groups (p=0.21). Bulky adenopathy (≥ 5 cm) was more common in patients with del(11q22.3) (89%), and complex cytogenetics were more likely in patients with del(17p13.1) (63%) versus del(11q22.3) (32%) or neither abnormality (26%) (p=0.003).

The overall response rate (ORR) was 46%, and was not significantly different among the cytogenetic groups (p=0.17). ORRs for patients classified with del(17p13.1), del(11q22.3), or without these abnormalities were 48%, 57%, and 34%, respectively. Significant differences in ORR were not observed between those with and without complex karyotype (39% versus 52%, p=0.25).

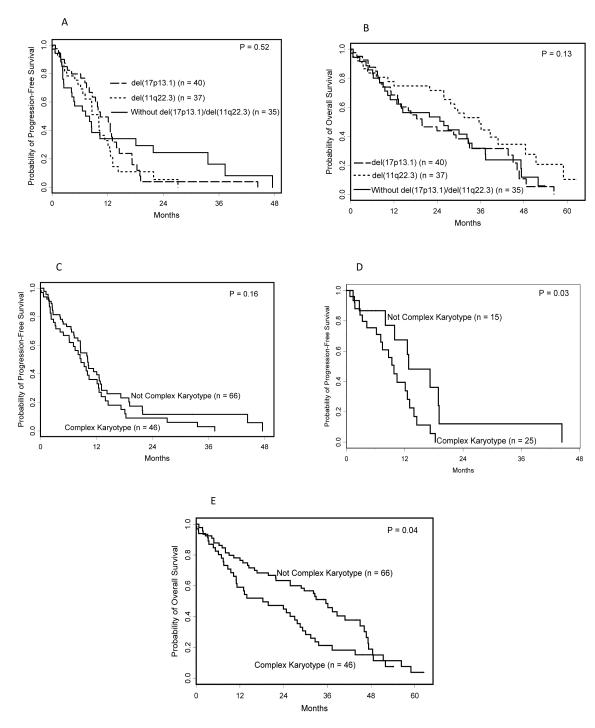

PFS was not significantly different among the cytogenetic groups (p=0.52), with estimated PFS of 10.4 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 8.0-13.0) for those classified as del(17p13.1), 10.1 months (95% CI: 6.6-11.4) for those classified as del(11q22.3), and 8.1 months (95% CI: 4.2-18.1) for those without these abnormalities (Figure 1a). The risk of progression, however, changed significantly over time, and PFS at 24 months for patients with del(17p13.1), del(11q22.3), and without these abnormalities were respectively, 4%, 5%, and 24%. PFS was not significantly different in patients with and without complex karyotype (median PFS: 8.7 (95% CI: 6.1-12.1) versus 10.1 (95% CI: 8.0-12.6) months respectively, p=0.16; Figure 1c), although, in the subset of patients with del(17p13.1), PFS was inferior for those with complex karyotype (median PFS: 9.8 (95% CI: 6.2-12.6) versus 12.8 months (95% CI: 8.0-19.1) respectively, p=0.03; Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing PFS and OS for patients treated with flavopiridol stratified by cytogenetic status and karyotypic complexity. PFS (1a) and OS (1b) are not significantly different among patients with del(17p13.1), del(11q22.3), or those without these high-risk markers. Among all patients, the presence of complex karyotype did not impact PFS (1c), however, in the subset of patients with del(17p13.1) (1d), patients with complex karyotype had inferior PFS. Complex karyotype was also significantly associated with inferior OS among all patients(1e).

Similarly, OS was not significantly different among the cytogenetic groups (p=0.13, Figure 1b), with median OS of 19.8 months (95% CI: 13.0-32.9) for patients with del(17p13.1), 35.6 months (95% CI: 25.8-48.4) for those with del(11q22.3), and 25.8 months (95% CI: 10.3-33.6) for patients without these abnormalities. The presence of complex karyotype, however, was associated with a significantly shorter OS (median OS: 18.3 (95% CI: 11.0-27.7) versus 35.6 months (95% CI: 25.8-45.0) respectively, p=0.04, figure 1e). This difference could largely be attributed to those patients with del(17p13.1) and complex karyotype.

In a multivariable model that included both cytogenetic group and complex karyotype, neither variable was significantly associated with ORR (p=0.21 and p=0.15 respectively). There were moderate differences in PFS between cytogenetic groups (patients with del(17p13.1)/del(11q22.3) versus others), when the hazard ratio was allowed to change over time (p=0.07; Table 1), with risk of progression for patients with del(17p13.1) or del(11q22.3) increasing over those without these abnormalities by 12 months of follow-up. The presence of complex karyotype did not add a significant amount of information in the model (p=0.29) and the only independent predictor of shorter PFS was the presence of bulky adenopathy (HR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.1-3.7; Table 1). No significant differences in OS were observed among the cytogenetic groups (p=0.24) in the multivariable model (Table 1). Complex cytogenetics were moderately associated with OS, independent of cytogenetic group (p=0.08), and number of prior therapies was significantly associated with OS (p=0.005). For each additional previous therapy received, the risk of death was 1.19 times higher (95% CI: 1.05-1.34).

Table 1.

Multivariable analysis of Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS)

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression-Free Survival | |||

| Cytogenetic group, (del(17p13.1)/del(11q22.3) vs. other)* at 3 months at 6 months at 12 months at 24 months |

0.74 1.06 1.54 2.23 |

0.41-1.33 0.63-1.81 0.81-2.93 0.95-5.27 |

0.07 |

| Complex Cytogenetics, (present vs. absent) | 1.28 | 0.81-2.02 | 0.29 |

| Age, 10 year increase | 0.89 | 0.70-1.12 | 0.31 |

| Rai Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.63 | 0.86-3.10 | 0.13 |

| Bulky lymphadenopathy, (present vs. absent) | 2.02 | 1.12-3.67 | 0.02 |

| Prior treatments, 1 unit increase | 1.00 | 0.90-1.12 | 0.94 |

| Treatment Schedule Initial Phase I Modified Phase I and II Dose escalation amended Phase II (reference group) |

1.20 1.01 --- |

0.62-2.33 0.57-1.77 --- |

0.81 |

| Overall Survival | |||

| Cytogenetic group* Del(17p13.1) Del(11q22.3) Other (reference group) |

1.21 0.72 --- |

0.66-2.22 0.39-1.34 --- |

0.24 |

| Complex Cytogenetics, (present vs. absent) | 1.55 | 0.95-2.54 | 0.08 |

| Age, 10 year increase | 1.11 | 0.86-1.42 | 0.42 |

| Rai Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.82 | 0.93-3.55 | 0.08 |

| Bulky lymphadenopathy, (present vs. absent) | 1.02 | 0.58-1.78 | 0.95 |

| Prior treatments, 1 unit increase | 1.19 | 1.05-1.34 | 0.005 |

| Treatment Schedule Initial Phase I Modified Phase I and II Dose escalation amended Phase II (reference group) |

1.12 0.96 --- |

0.53-2.38 0.51-1.81 --- |

0.86 |

NOTE: Hazard ratio >1 (<1) indicates increased (decreased) risk of an event for the first category listed for dichotomous variables or increased values of a continuous variable.

Cytogenetic group categorized using Dohner’s hierarchical classification. For PFS, the 3-level variable did not meet the proportional hazards assumption. Since the risk for patients with del(17p13.1) or del(11q22.3) relative to those without these two abnormalities was similar, the groups were combined and the hazard ratio was allowed to change over time using a time-dependent covariate. The p-value reflects a two-degree of freedom Wald chi-square test.

Of the 112 patients with cytogenetic data, 104 were evaluated for the mutational status of the TP53 gene. The mutation was found in 9 patients (9%, 95% CI: 4%-16%); all possessed del(17p13.1) and all but one had a complex karyotype. Four of these patients responded (44%). Because all patients with TP53 mutation had del(17p13.1), the impact of TP53 mutation was examined in the subset of patients with del(17p13.1). Patients with mutations in TP53 had a median PFS of 8.7 months (95% CI: 0.7-12.6), whereas those without had a median PFS of 10.4 months (95% CI: 8.0-14.5). OS was similar between these groups.

Collectively, these data show that patients with genetically high-risk disease detected by FISH who are treated with flavopiridol in the relapsed setting have similar outcomes to those without these abnormalities. Karyotypic complexity, however, is associated with inferior outcomes. As few studies have shown an impact of complex karyotype on outcome of a uniformly treated population, our data underscore the need for alternative treatment strategies, particularly in patients with del(17p13.1) and complex karyotype. It also identifies a group of patients in which early stem cell transplant should be considered.

Besides analysis with FISH and metaphase cytogenetics, we also performed an exploratory analysis of the relationship of TP53 mutation with PFS and OS in patients treated with flavopiridol. Our analysis contains relatively few patients with TP53 mutations given the number of patients with del(17p13.1) and the refractory patient population, however, the methodology described has been validated. We see a trend toward improved PFS for patients with del(17p13.1) who did not have TP53 mutation, though the number of patients with TP53 mutations is small. Other contributing features were also considered. Given the proposed mechanism of inhibition of CDK9 and transcriptional inhibition of short-half life proteins such as Mcl-1(14), we explored the relationship of change in Mcl-1 to flavopiridol response. While Mcl-1 generally decreases at the 4.5 hour time point post therapy, it rises by the second week of therapy. We have seen no correlation with either baseline Mcl-1 or change in Mcl-1 to response (supplementary Table 1 and 2). These exploratory findings will need to be confirmed with larger numbers of patients.

It has been demonstrated that patients with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities do not respond well to traditional chemotherapeutic agents and it is therefore appropriate to refer for clinical trials investigating flavopiridol or other non-chemotherapeutic agents in the up-front setting. Additionally, we have treated 19 patients with flavopiridol who went on to receive RIC allogeneic SCT, and 47% of these patients were able to proceed directly to transplant after flavopiridol therapy.(15) As flavopiridol is associated with a relatively low risk of infectious complications(13) it may be an appropriate agent for debulking prior to stem cell transplantation.

This analysis shows that agents like flavopiridol that work independently of the p53 pathway should be actively investigated in patients with genetically high-risk disease. Flavopiridol and other CDK inhibitors are attractive agents to study in the first-line setting for patients with poor-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, as well as to use in further single agent and combination studies in relapsed or refractory disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by Leukemia and Lymphoma Society SCOR grant, the D. Warren Brown Foundation, NIH/NCI; P01 CA81534, and 5KL2RR025754-02, P50-CA140158, 5K12 CA133250-03, N01-CM-62207, and U01 CA 076576. AJ is a Paul Calabresi Scholar.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Michael Grever and John Byrd have a use patent on flavopiridol that has not been awarded and currently lacks financial value.

References

- 1.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, Dohner K, Bentz M, Lichter P. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000 Dec 28;343(26):1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stilgenbauer S, Sander S, Bullinger L, Benner A, Leupolt E, Winkler D, Krober A, Kienle D, Lichter P, Dohner H. Clonal evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: acquisition of high-risk genomic aberrations associated with unmutated VH, resistance to therapy, and short survival. Haematologica. 2007 Sep;92(9):1242–1245. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt TD, Witzig TE, Fink SR, Jenkins RB, Paternoster SF, Smoley SA, Stockero KJ, Nast DM, Flynn HC, Tschumer RC, Geyer S, Zent CS, Call TG, Jelinek DF, Kay NE, Dewald GW. Prospective evaluation of clonal evolution during long-term follow-up of patients with untreated early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Oct 1;24(28):4634–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juliusson G, Robert KH, Ost A, Friberg K, Biberfeld P, Nilsson B, Zech L, Gahrton G. Prognostic information from cytogenetic analysis in chronic B-lymphocytic leukemia and leukemic immunocytoma. Blood. 1985 Jan;65(1):134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Gribben JG, Peterson BL, Grever MR, Lozanski G, Lucas DM, Lampson B, Larson RA, Caligiuri MA, Heerema NA. Select high-risk genetic features predict earlier progression following chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine and rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: justification for risk-adapted therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 20;24(3):437–443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, Hansen K, Benner A, Cabot G, Diehl D, Schlenk R, Coy J, Stilgenbauer S. p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non- response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood. 1995 Mar 15;85(6):1580–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wattel E, Preudhomme C, Hecquet B, Vanrumbeke M, Quesnel B, Dervite I, Morel P, Fenaux P. p53 mutations are associated with resistance to chemotherapy and short survival in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 1994 Nov 1;84(9):3148–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neilson JR, Auer R, White D, Bienz N, Waters JJ, Whittaker JA, Milligan DW, Fegan CD. Deletions at 11q identify a subset of patients with typical CLL who show consistent disease progression and reduced survival. Leukemia. 1997 Nov;11(11):1929–1932. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austen B, Powell JE, Alvi A, Edwards I, Hooper L, Starczynski J, Taylor AM, Fegan C, Moss P, Stankovic T. Mutations in the ATM gene lead to impaired overall and treatment-free survival that is independent of IGVH mutation status in patients with B-CLL. Blood. 2005 Nov 1;106(9):3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi D, Cerri M, Deambrogi C, Sozzi E, Cresta S, Rasi S, De Paoli L, Spina V, Gattei V, Capello D, Forconi F, Lauria F, Gaidano G. The prognostic value of TP53 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is independent of Del17p13: implications for overall survival and chemorefractoriness. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Feb 1;15(3):995–1004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zenz T, Eichhorst B, Busch R, Denzel T, Habe S, Winkler D, Buhler A, Edelmann J, Bergmann M, Hopfinger G, Hensel M, Hallek M, Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S. TP53 mutation and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. Oct 10;28(29):4473–4479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrd JC, Lin TS, Dalton JT, Wu D, Phelps MA, Fischer B, Moran M, Blum KA, Rovin B, Brooker-McEldowney M, Broering S, Schaff LJ, Johnson AJ, Lucas DM, Heerema NA, Lozanski G, Young DC, Suarez JR, Colevas AD, Grever MR. Flavopiridol administered using a pharmacologically derived schedule is associated with marked clinical efficacy in refractory, genetically high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):399–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin TS, Ruppert AS, Johnson AJ, Fischer B, Heerema NA, Andritsos LA, Blum KA, Flynn JM, Jones JA, Hu W, Moran ME, Mitchell SM, Smith LL, Wagner AJ, Raymond CA, Schaaf LJ, Phelps MA, Villalona-Calero MA, Grever MR, Byrd JC. Phase II study of flavopiridol in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrating high response rates in genetically high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec 10;27(35):6012–6018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen R, Keating MJ, Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Transcription inhibition by flavopiridol: mechanism of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell death. Blood. 2005 Oct 1;106(7):2513–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaglowski S, Flynn J, Jones J, Lin T, Fischer B, Scholl D, Elder P, Devine SM, Grever MR, Byrd JC, Andritsos LA. Flavopiridol is an effective therapy to bridge patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) to reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant. Blood. 2010;116(21) Abstract 2383. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.