Abstract

Purpose

National guidelines recommend that discussions about end-of-life (EOL) care planning happen early for patients with incurable cancer. We do not know whether earlier EOL discussions lead to less aggressive care near death. We sought to evaluate the extent to which EOL discussion characteristics, such as timing, involved providers, and location, are associated with the aggressiveness of care received near death.

Patients and Methods

We studied 1,231 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium, a population- and health system–based prospective cohort study, who died during the 15-month study period but survived at least 1 month. Our main outcome measure was the aggressiveness of EOL care received.

Results

Nearly half of patients received at least one marker of aggressive EOL care, including chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (16%), intensive care unit care in the last 30 days of life (9%), and acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%). Patients who had EOL discussions with their physicians before the last 30 days of life were less likely to receive aggressive measures at EOL, including chemotherapy (P = .003), acute care (P < .001), or any aggressive care (P < .001). Such patients were also more likely to receive hospice care (P < .001) and to have hospice initiated earlier (P < .001).

Conclusion

Early EOL discussions are prospectively associated with less aggressive care and greater use of hospice at EOL.

INTRODUCTION

Although patients with cancer are receiving increasingly aggressive care at the end of life (EOL),1,2 a growing body of evidence suggests that this trend could be modifiable; discussions between patients and their physicians about their preferences for EOL care are associated with less aggressive care near death.3–6 Current guidelines recommend that discussions about EOL care planning begin early in the disease course for patients with incurable cancer,7–12 during periods of relative medical stability rather than acute deterioration,7,8,11,13 and with physicians who know the patients well.7,8,11

Yet care often differs from these guidelines. In a prospective cohort study of 2,155 patients with metastatic lung or colorectal cancer in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS),14 we found that physicians initiated EOL discussions a median of 33 days before death. Most discussions took place in the inpatient setting, and even though most patients received longitudinal oncology care, conversations often occurred with nononcology physicians.

Although these attributes of EOL discussions conflict with current guidelines, their impact on care received at EOL is unknown. It is possible, for example, that early discussions have no greater impact on care than conversations that take place days before death. Previous work has generally relied on one-time, cross-sectional assessments of EOL conversations, without assessment of timing, location, or involved providers.3,4 In this study, we used prospective longitudinal data from patient and surrogate interviews and a comprehensive medical record review to prospectively evaluate the relationship between these factors and care received near death.

In addition, because we have observed that not every EOL discussion documented in medical records was reported by patients or their surrogates, despite specific interview questions designed to elicit such information,14 we assessed whether patient and surrogate recognition of EOL discussions was associated with EOL care received. Finally, we identified patient characteristics associated with patient or surrogate recognition of EOL discussions, relative to patients with documented but not reported discussions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The CanCORS cohort included approximately 10,000 patients age > 20 years who were diagnosed with all stages of lung or colorectal cancer between 2003 and 2005. Patients lived in northern California, Los Angeles County, North Carolina, Iowa, or Alabama or received their care in one of five large health maintenance organizations or one of fifteen Veterans Affairs sites.15 The study used cancer registry–based rapid case ascertainment, with the goal of identifying all newly diagnosed patients in the registry catchment area within weeks of diagnosis. Additional information about the CanCORS study is available elsewhere.16 The study was approved by human subjects committees at all participating institutions.

Patients (or surrogates of patients who were deceased or too ill to participate) were interviewed at baseline, approximately 4 to 6 months after diagnosis, by trained interviewers using computer-assisted telephone interviewing software. Interviews were offered in English, Spanish, or Chinese. Four versions of the baseline interview were available: a full patient interview; a brief patient interview, for patients unable to complete the full interview; a surrogate interview for surrogates of deceased patients; and a surrogate interview for living patients too ill to complete the interview.17 For patients alive at the time of the baseline interview, they or their surrogates were interviewed again approximately 15 months after diagnosis. The response rate in the CanCORS study, where the denominator included both unsuccessful contacts and refusal/nonresponse,18 was 51.0%. The cooperation rate, assessing participation among patients contacted, was 59.9%.16

Medical records from hospitals, radiation treatment facilities, and offices of medical oncologists, surgeons, gastroenterologists, pulmonologists, and primary care physicians were abstracted for the time period beginning 3 months before diagnosis until death or at least 15 months after diagnosis. Medical records were available for 87% of patients.

Study Cohort

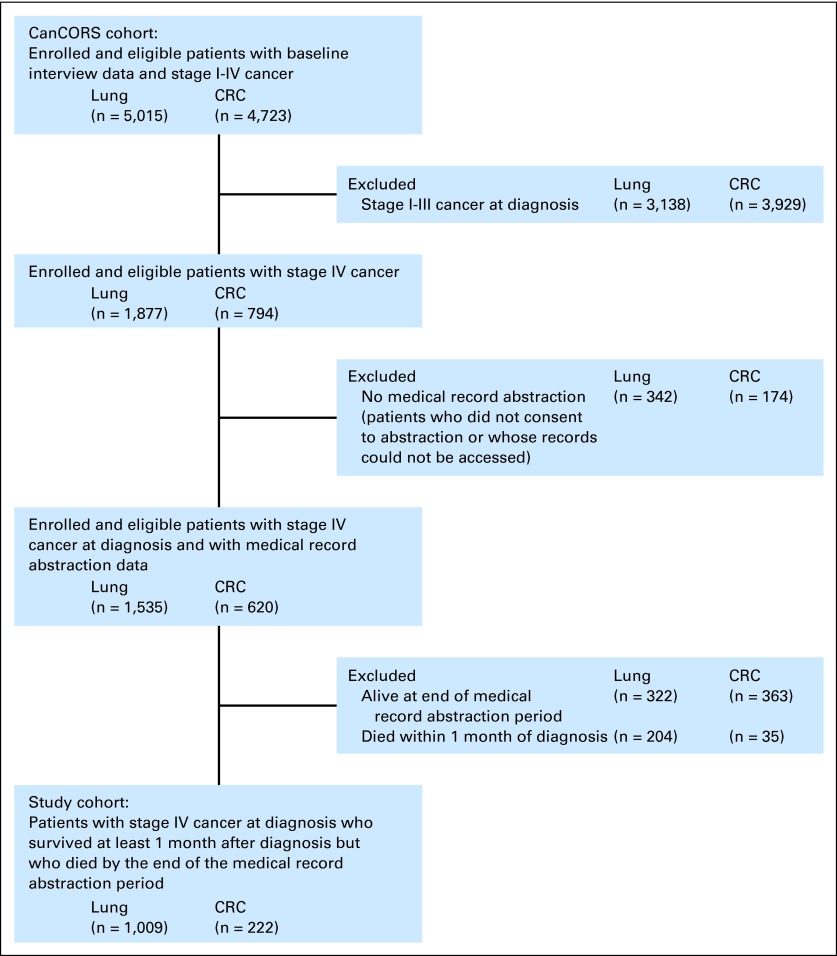

We focused on patients with stage IV disease at diagnosis. Such patients have incurable cancer and a limited life expectancy,19–23 making EOL discussions potentially appropriate. The cohort included 1,231 patients who survived at least 1 month after diagnosis, so our assessments of EOL discussion timing and care attributes were appropriate, and who died by the end of the medical record abstraction (MRA) period, so medical record data on EOL care were available (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Selection of analytic cohort. CanCORS, Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Definition of EOL Discussion

EOL discussions were identified if the patient or surrogate reported a discussion with the physician about resuscitation (eg, “Has a doctor ever talked to you about whether you would want to be revived or use life-sustaining machines?” from patient and surrogate interviews for living patients) or hospice care (eg, “After your cancer was diagnosed, did any doctor or other health care provider discuss hospice care with you?” from all interview types, or “Was hospice recommended by any doctor or other health care provider?” from follow-up interviews.)

EOL discussions were identified in medical records if there was documentation of a discussion about advance care planning (do-not-resuscitate order, hospice, palliative care, or not otherwise specified) or venue for dying (hospice, home, hospital, nursing home, or not otherwise specified). The earliest recorded EOL discussion in the medical record was considered the first EOL discussion for analysis. For each unique discussion in the medical record, we recorded the date, topics discussed, providers involved, and whether the discussion took place during hospitalization. For this analysis, we were interested in whether EOL discussions were reported by patients or surrogates versus documented in the medical record only as well as attributes of the first discussion, including the number of days before death, whether a medical oncologist was present, and whether the discussion occurred in the hospital.

EOL Care Received

We characterized EOL care received based on previously defined markers of aggressive care.1,24,25 Of note, the term aggressive care is widely used in the literature to describe care with high medical intensity. The measures we assessed are more likely to be undertaken with life-prolonging rather than palliative intent. However, the term aggressive is imperfect, because aggressive efforts may also be used to palliate symptoms. Nonetheless, in the absence of information about treatment intent (life prolongation v palliation) and benefit (beneficial v ineffective care), we use the term aggressive, with measures defined using information from the MRA and interviews:

Chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life.

Chemotherapy start date in the last 14 days of life (MRA), surrogate report of receipt of last chemotherapy regimen within 14 days of death, or surrogate report of death in hospital and receipt of chemotherapy during the last hospitalization.

Acute care in the last 30 days of life.

More than one emergency room visit in the last 30 days of life, more than one hospitalization in the last 30 days of life, more than 14 inpatient hospital days in the last 30 days of life (MRA), or death in hospital (MRA and surrogate interviews).

Intensive care unit care in the last 30 days of life.

Intensive care unit (ICU) admission date in the last 30 days of life, patient death in ICU, or use of defibrillation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ventilator, or intubation in the last 30 days of life (MRA).

Any aggressive EOL care.

Any of these outcomes (ie, chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life, acute care in the last 30 days of life, or ICU care in the last 30 days of life).

Hospice care.

Determined from the MRA and patient and surrogate interviews.

Hospice initiation in the last 7 days of life.

Determined from the MRA and surrogate interviews.

Statistical Analyses

After characterizing attributes of EOL care, bivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the association between attributes of EOL discussions (for the full sample, presence and source of EOL discussion; for MRA-documented discussions, days between first EOL discussion and death, presence of medical oncologist, and inpatient discussion) and aggressiveness of EOL care received. Multivariable logistic regression models were fitted for each marker of aggressive EOL care and hospice. The attributes of EOL discussions were included in multivariable models regardless of significance. Patient characteristics were sequentially removed from models using backward selection until remaining characteristics had a significance level ≤ .10.

Additional analyses were performed. First, we excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites, based on high rates of acute EOL care and the possibility that such patients may have received inpatient EOL care for palliation. Second, because surrogate interviews conducted after death were used to identify some EOL care attributes, we repeated analyses with a cohort restricted to patients for whom such interviews had been conducted. Finally, we repeated multivariable analyses defining the timing of EOL discussions as the number of days that discussions took place after diagnosis rather than days before death, adjusted for time between diagnosis and death. All findings were similar to results of the main analyses and are not presented.

Some patients had EOL discussions documented in their medical record, but the patient or surrogate did not report an EOL discussion; exploratory analyses were conducted to investigate characteristics of patients who did not recognize the documented discussion. This analysis was restricted to patients with a discussion about hospice or resuscitation documented in the MRA with a date that occurred before the baseline or follow-up interview date. Only discussions about hospice and resuscitation were considered, because these were the only topics queried in interviews.

Because of item nonresponse, a multiply-imputed data set was created using standard statistical methods.26,27 Imputed values were used for covariates in bivariable and multivariable analyses, but not for descriptive data in Table 1 or for missing patient or surrogate reports of EOL discussions or care. In the latter instance, MRA data were used to assess EOL discussions and care when patient or surrogate reports were not available. Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA (version 11.1; STATA, College Station, TX).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics (N = 1,231)

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex* | ||

| Male | 766 | 62 |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 935 | 76 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 152 | 12 |

| Asian | 53 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 59 | 5 |

| Other | 30 | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.2 |

| Marital status* | ||

| Married/living as married | 749 | 61 |

| Nonmarried | 476 | 39 |

| Unknown | 6 | 0.5 |

| Age, years* | ||

| 21-54 | 172 | 14 |

| 55-59 | 149 | 12 |

| 60-64 | 157 | 13 |

| 65-69 | 201 | 16 |

| 70-74 | 217 | 18 |

| 75-79 | 151 | 12 |

| ≥ 80 | 184 | 15 |

| Comorbidity score at diagnosis†‡ | ||

| None | 260 | 21 |

| Mild | 481 | 39 |

| Moderate | 244 | 20 |

| Severe | 246 | 20 |

| Speaks English at home§ | ||

| Yes | 1,133 | 92 |

| No | 39 | 3 |

| Missing | 59 | 5 |

| Education§ | ||

| < High school | 271 | 22 |

| High school/some college | 721 | 59 |

| ≥ College degree | 218 | 18 |

| Unknown | 21 | 2 |

| Income, $§ | ||

| < 20,000 | 367 | 30 |

| 20,000-39,999 | 339 | 28 |

| 40,000-59,999 | 151 | 12 |

| ≥ 60,000 | 179 | 15 |

| Unknown | 195 | 16 |

| Insurance* | ||

| Medicare | 178 | 14 |

| Medicaid | 156 | 13 |

| Medicare plus private | 442 | 36 |

| Private | 307 | 25 |

| Other | 142 | 12 |

| Unknown | 6 | 0.5 |

| HMO member∥ | ||

| Yes | 331 | 27 |

| No | 900 | 73 |

| Study site∥ | ||

| Five HMOs | 186 | 15 |

| Eight counties in northern California | 278 | 23 |

| Alabama | 157 | 13 |

| Los Angeles County | 198 | 16 |

| Iowa | 260 | 21 |

| 23 counties in North Carolina | 30 | 2 |

| 15 VA medical centers | 122 | 10 |

| Cancer type¶ | ||

| Lung | 1,009 | 82 |

| Colorectal | 222 | 18 |

| Baseline interview type | ||

| Patient full | 371 | 30 |

| Patient brief | 90 | 7 |

| Surrogate (living patient) | 124 | 10 |

| Surrogate (deceased patient) | 646 | 52 |

| Follow-up interview type | ||

| Survivor | 59 | 5 |

| Decedent | 370 | 30 |

| None | 802 | 65 |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; MRA, medical record abstraction; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Data obtained primarily from baseline interview; if nonresponse to interview item, then data obtained secondarily from MRA; if both data sources are missing, then data obtained from the administrative data (or tracking records).

Defined using Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27, a validated medical record–based system that assigns each patient a four-category comorbidity score (none, mild, moderate, or severe) based on severity noted across multiple body systems, from 3 months before diagnosis to initial treatment.28

Data obtained from MRA.

Data obtained from baseline or follow-up interviews.

Data obtained from administrative data (or tracking records).

Data obtained from administrative data (or tracking records).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. In the cohort study, 82% of patients had lung (v colorectal) cancer, reflecting our focus on patients with stage IV disease who died during the MRA period. EOL discussion attributes were similar to those we reported previously13 in an expanded cohort: 88% of patients in the current analysis had EOL discussions, either reported in both medical records and interviews (48%), in medical records only (17%), or in patient or surrogate interviews only (23%). Among 794 patients with EOL discussions reported in medical records, such that information about timing, involved physicians, and location was available, 39% of discussions took place in the last 30 days of life, 40% of discussions included an oncologist, and 63% took place in the inpatient hospital setting.

Aggressive EOL care included chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days of life (6%), and acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%; Table 2). Nearly half of patients received at least one of these three types of aggressive EOL care. Fifty-eight percent of patients received hospice care, which was initiated in the last 7 days of life for 15% of hospice users.

Table 2.

EOL Care Attributes (N = 1,231)

| Care | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive EOL care | ||

| Chemotherapy in last 14 days of life | 197 | 16 |

| Acute care in last 30 days of life | 496 | 40 |

| ICU care in last 30 days of life | 71 | 6 |

| Aggressive care | ||

| None | 649 | 53 |

| Any | 582 | 47 |

| Hospice care | ||

| None | 513 | 42 |

| Any* | 718 | 58 |

| Within 3 days of death | 59 | 8 |

| Within 7 days of death | 107 | 15 |

Abbreviation: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit.

Denominator used is number of patients with any hospice care (n = 718).

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had EOL discussions more than 30 days before death were less likely to receive aggressive EOL care and more likely to receive hospice care (Table 3). Similarly, aggressive EOL care was more common among patients whose first EOL discussions took place in the inpatient setting and less common when discussions were reported in interviews by patients and surrogates.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Associations Between Characteristics of EOL Discussions and EOL Care Received

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Chemotherapy Last 14 Days of Life |

Acute Care in Last 30 Days of Life |

ICU Care in Last 30 Days of Life |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| All patients | |||||||||||||

| No. | 1,231 | 16 | 40 | 6 | |||||||||

| Source of EOL discussion | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||

| No discussion | 149 | 26 | Reference | 48 | Reference | 5 | Reference | ||||||

| MR only | 205 | 21 | 0.77 | 0.47 to 1.26 | 61 | 1.67 | 1.09 to 2.56 | 13 | 2.56 | 1.12 to 5.83 | |||

| Survey only | 288 | 15 | 0.50 | 0.30 to 0.81 | 27 | 0.40 | 0.26 to 0.60 | 2 | 0.38 | 0.13 to 1.10 | |||

| MR plus survey | 589 | 12 | 0.39 | 0.25 to 0.60 | 37 | 0.63 | 0.44 to 0.90 | 5 | 0.98 | 0.44 to 2.18 | |||

| Patients with EOL discussion documented in MRA | |||||||||||||

| No. | 794 | 14 | 43 | 7 | |||||||||

| Days between first discussion and death | < .001 | < .001 | .002 | ||||||||||

| ≤ 30 | 311 | 21 | Reference | 58 | Reference | 12 | Reference | ||||||

| 31-60 | 186 | 10 | 0.40 | 0.23 to 0.69 | 41 | 0.51 | 0.35 to 0.73 | 5 | 0.43 | 0.21 to 0.90 | |||

| 61-90 | 108 | 8 | 0.34 | 0.16 to 0.70 | 32 | 0.34 | 0.22 to 0.55 | 6 | 0.45 | 0.18 to 1.10 | |||

| > 90 | 189 | 12 | 0.49 | 0.29 to 0.82 | 26 | 0.26 | 0.17 to 0.38 | 3 | 0.21 | 0.08 to 0.54 | |||

| Medical oncologist present at first discussion | .008 | .52 | .003 | ||||||||||

| No | 476 | 12 | Reference | 44 | Reference | 9 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 318 | 19 | 1.71 | 1.15 to 2.54 | 42 | 0.91 | 0.68 to 1.21 | 4 | 0.38 | 0.20 to 0.72 | |||

| Inpatient at first discussion | .02 | < .001 | .008 | ||||||||||

| No | 373 | 11 | Reference | 28 | Reference | 5 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 421 | 17 | 1.65 | 1.10 to 2.49 | 57 | 3.48 | 2.58 to 4.68 | 10 | 2.20 | 1.22 to 3.95 | |||

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Any Aggressive Care |

Any Hospice Care |

Hospice Care Within 7 Days of Death (n = 718)* |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | Yes (%) | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| All patients | |||||||||||||

| No. | 1,231 | 47 | 58 | 15 | |||||||||

| Source of EOL discussion | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||

| No discussion | 149 | 59 | Reference | 20 | Reference | 17 | Reference | ||||||

| MR only | 205 | 67 | 1.40 | 0.90 to 2.16 | 29 | 1.64 | 0.99 to 2.71 | 40 | 3.33 | 1.12 to 9.92 | |||

| Survey only | 288 | 36 | 0.39 | 0.26 to 0.58 | 64 | 7.12 | 4.46 to 11.4 | 3 | 0.14 | 0.04 to 0.51 | |||

| MR plus survey | 589 | 43 | 0.51 | 0.36 to 0.74 | 75 | 12.0 | 7.74 to 18.7 | 16 | 0.99 | 0.37 to 2.66 | |||

| Patients with EOL discussion documented in MRA | |||||||||||||

| No. | 794 | 49 | 63 | 12 | |||||||||

| Days between first discussion and death | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||

| ≤ 30 | 311 | 65 | Reference | 49 | Reference | 36 | Reference | ||||||

| 31-60 | 186 | 45 | 0.44 | 0.30 to 0.64 | 68 | 2.28 | 1.56 to 3.34 | 9 | 0.18 | 0.09 to 0.36 | |||

| 61-90 | 108 | 37 | 0.32 | 0.20 to 0.51 | 74 | 3.03 | 1.87 to 4.91 | 13 | 0.25 | 0.12 to 0.52 | |||

| > 90 | 189 | 34 | 0.28 | 0.19 to 0.41 | 77 | 3.49 | 2.33 to 5.23 | 14 | 0.28 | 0.16 to 0.50 | |||

| Medical oncologist present at first discussion | .71 | .005 | .09 | ||||||||||

| No | 476 | 48 | Reference | 59 | Reference | 17 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 318 | 50 | 1.06 | 0.80 to 1.40 | 69 | 1.53 | 1.13 to 2.07 | 23 | 1.48 | 0.95 to 2.30 | |||

| Inpatient at first discussion | < .001 | .001 | .004 | ||||||||||

| No | 373 | 35 | Reference | 69 | Reference | 14 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 421 | 62 | 3.02 | 2.26 to 4.04 | 58 | 0.62 | 0.46 to 0.83 | 24 | 1.94 | 1.23 to 3.05 | |||

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit; MR, medical record; MRA, medical record abstraction; OR, odds ratio.

For the subgroup of 718 patients who received hospice.

In adjusted analyses, results were similar (Table 4). Patient- and surrogate-reported EOL discussions were significantly associated with EOL care received, but discussions documented in the medical record in the absence of patient or surrogate report were not. Among patients or surrogates who reported EOL discussions, those that occurred earlier were associated with less aggressive EOL care for all measures except ICU care. Patients who were hospitalized at the time of their first EOL discussion were more likely to receive acute care and ICU-based care in the last month of life and to initiate hospice within the last week of life. Having a medical oncologist present at the first discussion slightly increased the odds of chemotherapy receipt in the last 14 days of life. Although patients whose oncologists were present at the first discussion were slightly more likely to receive hospice care, hospice was also more commonly initiated in the last week of life.

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression

| Characteristic | Chemotherapy in Last 14 Days of Life* |

Acute Care in Last 30 Days of Life† |

ICU Care in Last 30 Days of Life‡ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| EOL discussion | |||||||||

| No discussion | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| MR only | 0.81 | 0.44 to 1.48 | .49 | 1.16 | 0.70 to 1.91 | .57 | 2.02 | 0.78 to 5.23 | .15 |

| Patient/surrogate reported (survey only or MR plus survey) | 0.41 | 0.25 to 0.66 | < .001 | 0.43 | 0.29 to 0.65 | < .001 | 0.77 | 0.33 to 1.80 | .55 |

| Days between first EOL discussion and death | .003 | < .001 | .16 | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 31-60 | 0.42 | 0.24 to 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.44 to 0.94 | 0.65 | 0.31 to 1.35 | |||

| 61-90 | 0.38 | 0.18 to 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.27 to 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.28 to 1.69 | |||

| > 90 | 0.74 | 0.43 to 1.25 | 0.42 | 0.28 to 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.14 to 0.95 | |||

| Medical oncologist present at first discussion | 1.48 | 1.00 to 2.19 | .049 | 0.96 | 0.70 to 1.31 | .79 | 0.44 | 0.22 to 0.85 | .01 |

| Inpatient at first discussion | 1.11 | 0.75 to 1.63 | .61 | 3.06 | 2.29 to 4.10 | < .001 | 2.77 | 1.56 to 4.91 | < .001 |

| Characteristic | Any Aggressive Care§ |

Any Hospice Care∥ |

Hospice Care Within 7 Days of Death (n = 718)¶ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| EOL discussion | |||||||||

| No discussion | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| MR only | 1.13 | 0.68 to 1.89 | .64 | 0.99 | 0.56 to 1.73 | .96 | 2.17 | 0.64 to 7.38 | .21 |

| Patient/surrogate reported (survey only or MR plus survey) | 0.40 | 0.27 to 0.60 | < .001 | 6.88 | 4.36 to 10.8 | < .001 | 0.43 | 0.14 to 1.30 | .13 |

| Days between first EOL discussion and death | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 31-60 | 0.52 | 0.36 to 0.76 | 1.90 | 1.28 to 2.84 | 0.23 | 0.11 to 0.48 | |||

| 61-90 | 0.38 | 0.24 to 0.61 | 2.94 | 1.74 to 4.98 | 0.36 | 0.16 to 0.79 | |||

| > 90 | 0.46 | 0.31 to 0.68 | 2.94 | 1.94 to 4.46 | 0.50 | 0.26 to 0.97 | |||

| Medical oncologist present at first discussion | 1.11 | 0.82 to 1.50 | .52 | 1.43 | 1.03 to 1.98 | .03 | 2.06 | 1.26 to 3.38 | .004 |

| Inpatient at first discussion | 2.47 | 1.85 to 3.29 | < .001 | 0.80 | 0.59 to 1.08 | .15 | 3.43 | 2.08 to 5.64 | < .001 |

NOTE. Separate models are fit for each aggressive care outcome.

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit; MR, medical record; OR, odds ratio; PDCR, primary data collection region.

Adjusted for survival time, sex, race/ethnicity, English speaking, and PDCR.

Adjusted for survival time, race/ethnicity, income, and PDCR.

Because of limited number of events, patient characteristics were not controlled for.

Adjusted for age, survival time, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, and PDCR.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity and PDCR.

For the subgroup with any hospice care; adjusted for survival time, comorbidity, and PDCR.

Of 634 patients with an EOL discussion about resuscitation or hospice documented in the medical record that took place before a patient or surrogate interview, 526 (83%) had a patient- or surrogate-reported discussion. After adjustment for all other factors (Table 5), patients were less likely to report documented discussions if they were unmarried, black or Hispanic (v white), or not enrolled in a health maintenance organization.

Table 5.

Patient Characteristics Associated With Patient/Surrogate Report of EOL Discussion

| Characteristic | Unadjusted |

Adjusted* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR† | 95% CI | P | OR† | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | .20 | .76 | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 1.33 | 0.86 to 2.07 | 1.09 | 0.64 to 1.85 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | .005 | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black | 0.41 | 0.23 to 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.19 to 0.73 | ||

| Asian | 0.84 | 0.28 to 2.52 | 1.33 | 0.38 to 4.68 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.19 | 0.09 to 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.12 to 0.73 | ||

| Other | 0.23 | 0.08 to 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.10 to 1.12 | ||

| Marital status | .17 | .04 | ||||

| Married/living as married | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Nonmarried | 1.37 | 0.88 to 2.13 | 1.73 | 1.02 to 2.94 | ||

| Age, years | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.02 | .94 | — | ||

| Comorbidity score at diagnosis | .74 | |||||

| None | Reference | — | ||||

| Mild | 1.38 | 0.77 to 2.50 | — | |||

| Moderate | 1.33 | 0.69 to 2.54 | — | |||

| Severe | 1.23 | 0.65 to 2.35 | — | |||

| Speaks English in home | .02 | .46 | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 0.30 | 0.11 to 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.15 to 2.35 | ||

| Education | .55 | |||||

| < High school | Reference | — | ||||

| High school/some college | 0.85 | 0.51 to 1.43 | — | |||

| ≥ College degree | 0.69 | 0.36 to 1.33 | ||||

| Income, $ | .60 | |||||

| < 20,000 | Reference | — | ||||

| 20,000-39,999 | 1.18 | 0.69 to 2.02 | — | |||

| 40,000-59,999 | 1.02 | 0.54 to 1.94 | — | |||

| ≥ 60,000 | 0.76 | 0.41 to 1.39 | — | |||

| Insurance | .047 | .48 | ||||

| Medicare | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Medicaid | 0.43 | 0.20 to 0.91 | 0.45 | 0.19 to 1.08 | ||

| Medicare plus private | 0.96 | 0.49 to 1.86 | 0.69 | 0.32 to 1.47 | ||

| Private | 1.12 | 0.54 to 2.35 | 0.75 | 0.32 to 1.73 | ||

| Other | 0.77 | 0.34 to 1.74 | 0.86 | 0.36 to 2.06 | ||

| HMO member | .01 | .03 | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 0.51 | 0.30 to 0.86 | 0.40 | 0.18 to 0.90 | ||

| Study site | < .001 | .06 | ||||

| Five HMOs | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Eight counties in northern California | 0.45 | 0.19 to 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.28 to 2.38 | ||

| Alabama | 0.80 | 0.27 to 2.36 | 2.08 | 0.50 to 8.63 | ||

| Los Angeles County | 0.22 | 0.10 to 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.18 to 1.50 | ||

| Iowa | 0.58 | 0.25 to 1.30 | 1.07 | 0.33 to 3.42 | ||

| 23 counties in North Carolina | ‡ | ‡ | ||||

| 15 VA medical centers | 0.29 | 0.12 to 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.14 to 1.83 | ||

| Cancer type | .80 | |||||

| Lung | Reference | — | ||||

| Colorectal | 0.93 | 0.52 to 1.66 | — | |||

| Survival time from diagnosis, weeks | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.02 | .47 | — | ||

| Baseline interview type | .04 | .03 | ||||

| Patient full | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Patient brief | 0.41 | 0.17 to 0.99 | 0.33 | 0.12 to 0.86 | ||

| Surrogate (living patient) | 2.35 | 0.77 to 7.21 | 2.30 | 0.70 to 7.54 | ||

| Surrogate (deceased patient) | 0.76 | 0.45 to 1.30 | 1.12 | 0.35 to 3.62 | ||

| Follow-up interview type | .14 | .21 | ||||

| Survivor | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Decedent | 2.66 | 0.77 to 9.12 | 3.10 | 0.79 to 12.1 | ||

| None | 1.77 | 0.54 to 5.80 | 1.73 | 0.33 to 9.12 | ||

NOTE. Of 634 patients with a documented discussion, 526 (83%) also had patient/surrogate report the discussion.

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; HMO, health maintenance organization; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for variables with P < .20 on univariate analysis.

ORs and P values are from logistic regression.

All North Carolina patients/surrogates recognized discussion.

DISCUSSION

National guidelines recommend that conversations about EOL care take place soon after diagnosis for patients with incurable cancer.7,8 We found that patients who had earlier discussions about EOL care were less likely to receive aggressive measures before death. Use of aggressive care was much less frequent when EOL discussions took place at any time before the last 30 days of life, and the odds of hospice use were nearly twice as high.

Others have suggested that EOL decision making requires time11,29,30; most patients need to process the idea that life is nearing its end before they can make decisions about their EOL care. When discussions begin in the last 30 days of life, the EOL period is typically already under way. Importantly, clinicians may not know when the last month of life is about to begin. However, physicians seem to wait until the patient begins deteriorating medically, a strategy that leads to a high incidence of inpatient discussions. Instead, physicians should consider moving conversations closer to diagnosis and initiating conversations while the patient is doing comparatively well, so the patient has time to plan for more difficult times in the future.

Just as late discussions were associated with more aggressive EOL care, discussions in the inpatient hospital setting had similar outcomes. However, inpatient discussions may not necessarily cause more aggressive care; instead, once patients are hospitalized, EOL discussions may be expected.

Importantly, we do not know whether earlier discussions would change the tenor of care received at EOL, because our data cannot address causation. However, our data do describe two widely divergent paths of care at EOL. One path is characterized by early discussions about EOL care, greater use of hospice care including early hospice initiation, and less use of aggressive care. The alternative path features EOL discussions that start in the last 30 days of life (or never take place), accompanied by aggressive care in the last month and less and later hospice initiation. Did patients on the second path receive the care they wanted? We do not know. However, we do know that these patients did not have the opportunity to express their preferences for EOL care until their last month of life was already under way.

We also found that some EOL discussions were not recognized or reported by patients or surrogates, and only patient- or surrogate-recognized conversations were associated with less aggressive care. Every physician has probably at times said words to patients that were not heard or understood, and the finding of documented but unrecognized discussions may be an example of this. Our data lacked nuanced information about why this occurred, including details on content and length of the discussions. For surrogate interviews, we also cannot be sure that the surrogate was present for the documented discussion. However, exploratory analyses identified select groups of patients who were at particular risk for unrecognized conversations, including black and Hispanic patients. Given the known racial disparities in care at EOL, further work should examine how conversations may have differed and which communication needs may have been unmet in these groups.

Of note, documented but unrecognized EOL discussions were not associated with less aggressive care. Although patients who desired aggressive care may have been less likely to recognize or report such conversations, it is also possible that more effective communication may have allowed patients to hear these conversations and make alternate care plans. These findings underscore the critical need for physicians to assess patients' understanding after important conversations.

This study has several limitations. As we have noted, CanCORS documented the presence of EOL discussions without evaluating the content or quality of discussions. Although some data suggest that palliative care consults for patients who die in the hospital may be cost saving, we found limited impact of EOL discussions among hospitalized patients, possibly because we could not assess the content of the discussions. Multiple sources of data were used without full agreement between sources about whether EOL discussions took place. However, combined data from patient and surrogate interviews and medical records are likely to be more complete than any one source, and our sensitivity analyses suggested that when we limited the cohort to patients with data measured in a consistent way, using surrogate reports after death to characterize EOL care, results were similar. In addition, discrepancies between sources allowed us to explore unique issues such as the lack of patient recognition of conversations. We also relied on MRA data covering the first 15 months after diagnosis and excluded patients who lived longer, including many patients with colorectal cancer. Patterns of care may have been different for such patients. However, adjustment for survival time and diagnosis did not significantly change our findings. Finally, some of our markers of aggressive care, such as ICU care, were rare. Nonetheless, relationships with EOL discussion attributes were similar to those for more common events.

Aggressive care is not necessarily wrong for individuals at EOL; it may fit with the preferences of select patients who want to pursue life prolongation at any cost. But most patients who recognize that they are dying do not want such care.3–5 Evidence suggests that less aggressive care is also less costly31–33 and less burdensome for surviving family members.3,34 Given the many arguments for less aggressive EOL care, earlier discussions have the potential to change the way EOL care is delivered for patients with advanced cancer and help to assure that care is consistent with patients' preferences.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) and to the NCI-supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network [U01 CA093332], Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center [U01 CA093324], RAND/University of California at Los Angeles [U01 CA093348], University of Alabama at Birmingham [U01 CA093329], University of Iowa [U01 CA093339], and University of North Carolina [U01 CA093326]); by a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) grant to the Durham VA Medical Center (CRS 02-164); and by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant and the National Palliative Care Research Center (J.W.M.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jennifer W. Mack, Nancy L. Keating, Haiden A. Huskamp, Jennifer L. Malin, Craig C. Earle, Jane C. Weeks

Financial support: Jane C. Weeks

Collection and assembly of data: Jane C. Weeks

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1587–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prigerson HG. Determinants of hospice utilization among terminally ill geriatric patients. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1991;12:81–112. doi: 10.1300/j027v12n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 8.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/Guidelines_Download2.aspx.

- 9.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:755–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo B, Quill T, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients: ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel—American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life: Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients—Addressing the “elephant in the room.”. JAMA. 2000;284:2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330:1007–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:204–210. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of participants in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium relative to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Med Care. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. epub ahead of print on March 7, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients' experience and outcomes: Development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. http://www.aapor.org/uploads/Standard_Definitions_04_08_Final.pdf.

- 19.Kato I, Severson RK, Schwartz AG. Conditional median survival of patients with advanced carcinoma: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data. Cancer. 2001;92:2211–2219. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2211::aid-cncr1565>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackstock AW, Herndon JE, 2nd, Paskett ED, et al. Outcomes among African-American/non-African-American patients with advanced non-small-cell lung carcinoma: Report from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:284–290. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.4.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earle CC, Venditti LN, Neumann PJ, et al. Who gets chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer? Chest. 2000;117:1239–1246. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:505–509. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y. Missing data analysis using multiple imputation: Getting to the heart of the matter. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:98–105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.875658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Landrum MB, et al. Multiple imputation in a large-scale complex survey: A practical guide. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;19:653–670. doi: 10.1177/0962280208101273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593–602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Block S. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life. JAMA. 2001;285:2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1096–1105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]