Abstract

Background

The diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (DSV-PTC) is a unique variant of PTC that is characterized by extensive lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells in a background of lymphocytic thyroiditis. The lymphatic emboli contain tumor cells as well as macrophages, but the recruitment of these macrophages is not well understood. The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between the expression of Decoy receptor 3 (DcR3), the recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and lymphatic invasion in DSV-PTC.

Methods

We retrospectively examined 14 cases of DSV-PTC using immunohistochemistry studies. The density of TAMs, lymphatic vessel density, lymphatic invasion, tumor emboli area, and DcR3 expression were assessed. Statistical analyses were performed using Fisher's exact test, unpaired t-test, and linear regression.

Results

The lymphatic tumor emboli contained a relatively higher density of TAMs than stroma and classical PTC (CPTC) areas. In addition, the number of lymphatic invasions and the size of the tumor emboli area were positively correlated with the number of M2 TAMs. A higher density of M2 TAMs was associated with older patients and larger tumor size. Moreover, DcR3 was expressed only in lymphatic tumor cells and squamous metaplastic tumor cells, but not in macrophages and CPTC. In addition, the preferential expression of DcR3 in tumors was associated with higher levels of M2 TAMs and lymphatic invasion.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that the exact relationship between DcR3, M2 macrophages, and lymphatic invasion in DSV-PTC remains to be elucidated, our findings suggest that DcR3 expression in DSV-PTC tumor cells may promote the polarized macrophage differentiation toward the M2 phenotype. This phenomenon may further promote lymphatic invasion of DSV-PTC tumor cells.

Introduction

The diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (DSV-PTC) is a unique variant of PTC that is characterized by extensive lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells in a background of lymphocytic thyroiditis. Lymph node (LN) metastases in DSV-PTC are also frequently observed at the time of diagnosis. The prognosis of this variant is still under debate, as some studies have shown poorer prognosis (1,2) than other well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas.

In a preliminary study, we found that the lymphatic tumor emboli in DSV-PTC are mixed together with many macrophages. This peculiar phenomenon evoked our interest to investigate the role of these tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). TAMs have been previously described in various malignant tumors, including carcinomas of the lung (3,4), pancreas (5,6), larynx (7), endometrium (8), kidney (9), and colorectum (10), as well as in lymphomas (11,12). However, the functional role of TAMs in thyroid cancer was not clear until the publication of two recent reports (13,14), in which TAM infiltration was significantly increased in poorly or undifferentiated carcinomas, and was associated with poor prognosis in these patients.

It has been known that M1-polarized macrophages show tumor-suppressive functions and are capable of killing microorganisms or tumor cells, whereas M2-polarized macrophages, in contrast, display tumor-supportive functions and have important roles in angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, matrix remodeling, and tumor metastasis. Furthermore, higher densities of M2-polarized macrophages are associated with more aggressive behavior and poor outcome in many malignant tumors (4–6,9,11–13). Recent studies have shown that Decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) is capable of modulating macrophage differentiation toward the M2 phenotype (5,15), specifically by down-regulation of MHC class II expression in TAMs.

In this study, we describe a unique phenomenon of preferential expression of DcR3 and dominant infiltration of M2 macrophages in DSV-PTC, which significantly correlates with the peculiar pattern of massive intralymphatic growth in this tumor.

Materials and Methods

Clinicopathological analysis

We retrieved a total of 14 surgical cases of DSV-PTC from 1020 cases of PTC in our pathology archive of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The pathology slides were reviewed by two authors (W.-C.C. and A.-H.Y.), and the pathological diagnosis of DSV-PTC was based on the criteria described in the 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) scheme (16). All cases in this study group were staged according to the AJCC/UICC TNM system (17). All patient material was processed following the ethics regulations of the Institutional Review Board of the hospital. The clinical and follow-up data were collected by reviewing the patient's medical records. For patient management, we generally follow the guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (18). In addition to total thyroidectomy, prophylactic central LN dissection (LND) was performed unless there was a high risk of permanent hypoparathyroidism or to prevent injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Therapeutic central and lateral LND were performed if the LN was palpable or if biopsy of nodes was positive for metastasis. Adjuvant radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation is usually applied for high-risk types of PTC. The dosimetry of RAI therapy was adjusted if metastasis existed. External beam radiotherapy was usually chosen for tumors not responsive to RAI treatment. Chemotherapy was considered if other treatment modalities failed. Patients who were alive and without clinical or pathological evidence of disease recurrence or metastasis on the latest follow-up were designated as AND (alive no disease), while those with clinical (confirmed by RAI whole-body scan) or pathological (confirmed by cytologic or histopathological examination) evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease on the latest follow-up were designated as AWD (alive with disease).

Immunohistochemical and morphometric analyses

We performed immunohistochemical staining on 4 μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections following routine procedures. The working conditions of primary antibodies are listed in Table 1. All sections were labeled using a polymer-HRP staining kit (BOND™; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and double staining for CD68/CD163 and DcR3/TTF-1 was labeled using an additional polymer-AP staining kit (BOND; Leica Microsystems). Adequate immunoreactive tissue samples from the tonsils and lungs were used as positive controls. Sections stained without the primary antibody were used as negative controls. The stained sections were digitized using a Nikon DS-Fi1 digital microscope camera, and analyzed using ImageJ software (v. 1.44, National Institutes of Health).

Table 1.

Monoclonal Antibodies and Pretreatment Methods

| Antigen | Clone | Type | Dilution | Source | Pretreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD68 | PG-M1 | Mouse | 1:50 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | HIER, citrate buffer (pH 6.0) |

| CD163 | 10D6 | Mouse | 1:100 | Novocastra (Burlingame, CA) | HIER, citrate buffer (pH 6.0) |

| D2-40 | D2-40 | Mouse | 1:75 | Dako | HIER, Tris buffer (pH 9.0) |

| DcR3 | ab57956 | Mouse | 1:300 | Abcam (Cambridge, MA) | HIER, Tris buffer (pH 9.0) |

| TTF-1 | 8G7G3/1 | Mouse | 1:40 | Dako | HIER, Tris buffer (pH 9.0) |

HIER, heat-induced epitope retrieval; DcR3, Decoy receptor 3.

Macrophages within the tumor emboli, stroma, or classical PTC (CPTC) were separately assessed by CD68 staining. M2 macrophages were identified by CD163 staining. Sections were initially scanned at low magnification (100×) to identify the areas with the highest density of TAMs (TAM hot-spots). Average TAM count was assessed by counting a minimum of five TAM hot-spots at 200× (0.28 mm2) magnification on the digitized photomicrograph. The total area of lymphatic tumor emboli was measured to calculate the actual macrophage density.

Lymphatic vessel density (LVD) was defined as the mean D2-40 positive lymphatic channels in five random 100× (1.12 mm2) fields. The lymphatic invasion index (LI) was defined as the average number of tumor cell–containing D2-40–positive lymphatic channels in five random 100× fields. The tumor emboli area was defined as the average area of lymphatic tumor emboli in five random 100× fields.

The expression of DcR3 was defined as the percentage of cells with unequivocal cytoplasmic staining. The tumors expressing low levels of DcR3 were defined as <10% of total tumor cells with positive cytoplasmic staining, whereas the other tumors were classified as high-expressing tumors. Co-localization of DcR3 and TTF-1 was assessed by double staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (v. 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism (v. 5.0; La Jolla, California, USA). The median value of macrophage count was used as a cut-off point to dichotomize the continuous variables. Fisher's exact test was used to compare between categorical variables, and unpaired two-sided t-test was used to compare between continuous variables. Linear regression was used to analyze the correlation between two continuous variables. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological findings

The clinicopathological features of the 14 DSV-PTCs are summarized in Table 2. In brief, the average age of patients at initial presentation was 35.4 years (range 13–61 years), and there was a female predominance (F:M=3.7:1). All patients received total thyroidectomy with or without LND. Eight patients received additional RAI treatment, and three received additional radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. The mean follow-up time was 47 months (range 1–165 months). In addition to the typical histopathological features of DSV-PTC (Fig. 1A, B), five cases also harbored a main tumor mass consisting of CPTC (Fig. 1C). Extrathyroid extension was observed in 9 (64%) cases. Vascular invasion in the perithyroid tissue was found in 3 (21%) cases. Twelve (86%) cases had local cervical LN metastasis at initial presentation. Recurrence of tumor or LN metastasis on subsequent follow-up was observed in 5 (37%) cases. Distant metastases were noted in 3 (21%) cases, with the lung as the most common metastatic site. Nine tumors were classified as stage I (64.3%), 1 as stage II (7.1%), 2 as stage IVa (14.3%), and 2 as stage IVc (14.3%).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological Features of Patients with Diffuse Sclerosing Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

| No. | Age/sex | Tumor size (cm) | VI | ETE | Adjuvant Tx | LN MTS (no./total) | Recurrence | Distant MTS (site) | pTNM | FU (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25/F | 1.8 | No | No | Yesa | 1/1 | No | No | T1b(m)N1aMx | AND (165) |

| 2 | 33/F | 4 | No | Yes | No | NA | No | Lung | T3(m)NxM1 | DOD (1) |

| 3 | 25/M | 2.1 | No | No | Yesa | NA | Yes | No | T2(m)NxMx | AND (145) |

| 4 | 45/F | 4 | No | Yes | Yesb | 6/7 | No | No | T3(m)N1bMx | AND (56) |

| 5 | 27/F | 1 | No | Yes | Yesa | 6/6 | Yes | No | T3(m)N1bMx | AND (76) |

| 6 | 31/F | 2.5 | Yes | No | Yesa | 11/35 | No | No | T2N1bMx | AND (47) |

| 7 | 40/F | 0.3 | No | No | Yesa | 10/30 | No | No | T1(m)N1bMx | AND (48) |

| 8 | 61/F | 4 | No | Yes | Yesa | 17/17 | Yes | Lung, liver, brain, bone | T3(m)N1bM1 | AWD (38) |

| 9 | 23/F | 0.5 | No | Yes | Yesa | 20/21 | Yes | No | T3(m)N1bMx | AWD (36) |

| 10 | 52/F | 5.5 | Yes | Yes | Yesb | 10/10 | Yes | No | T3(m)N1bMx | DOD (2) |

| 11 | 60/F | 4.6 | Yes | Yes | Yesb | 27/38 | Yes | Pericardium, lung | T3(m)N1aM1 | DOD (5) |

| 12 | 31/M | 5.5 | No | Yes | Yesa | 16/35 | No | No | T3(m)N1aMx | AND (16) |

| 13 | 30/M | 2 | No | No | No | 4/4 | No | No | T2N1aMx | AND (9) |

| 14 | 13/F | 2.1 | No | Yes | No | 8/15 | No | No | T3(m)N1bMx | AND (9) |

Patients received radioactive iodine therapy.

Patients received radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

(m), multifocal tumor; AND, alive no disease; AWD, alive with disease, DOD, died of disease; ETE, extrathyroid extension; F, female; FU, follow-up; LN, lymph node; M, male; MTS, metastasis; NA, not available; VI, vascular invasion.

FIG. 1.

Histopathological features of diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (DSV-PTC). (A) Representative photomicrograph shows characteristic dense stromal fibrosis in a background of lymphocytic thyroiditis, extensive lymphatic invasion, squamous metaplasia, and numerous psammoma bodies (H&E, scale bar: 500 μm). (B) Immunohistochemical staining showing D2-40 positive lymphatic channels containing massive tumor emboli (scale bar: 500 μm). (C) A representative case shows a main tumor region (upper left) composed of classical PTC (H&E, scale bar: 100 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Distribution and quantity TAMs in DSV-PTC

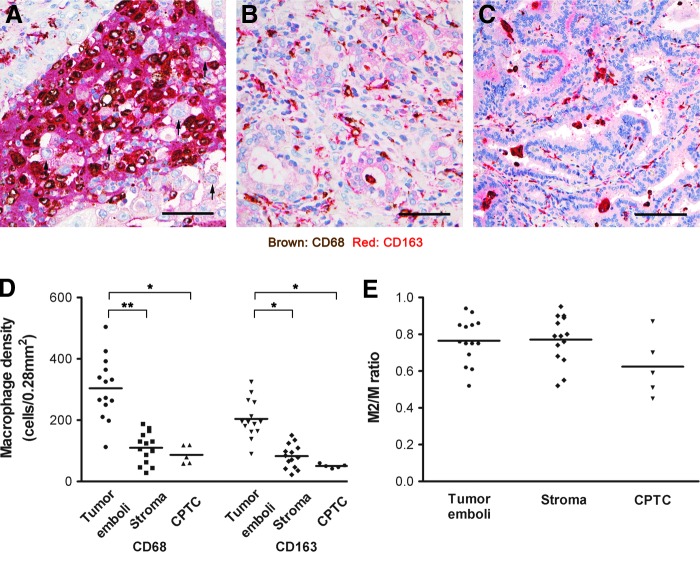

CD68/CD163 double staining showed that TAMs are more concentrated in the lymphatic tumor emboli, with the majority (76%) of macrophages being of the M2 phenotype (Fig. 2A–C). Although macrophage density in stroma and CPTC were noticeably lower than in lymphatic tumor emboli (Fig. 2D), the proportions of M2 macrophages (M2/M ratios) were similar to those in lymphatic tumor emboli (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of CD68- and CD163-positive macrophages in DSV-PTC. Representative photomicrographs show double immunohistochemical staining of CD68- and CD163-positive macrophages in (A) tumor emboli, (B) stromal and (C) classical PTC (CPTC). The majority of CD68-positive macrophages are also positive for CD163. All tumor cells (arrows) are negative for both stains (scale bars: 50 μm). (D) Quantitative analyses show that the density of CD68- and CD163-positive macrophages are significantly higher in the emboli than those in the stromal (p<0.005) and CPTC (p<0.001) areas. (E) The M2/M ratio in the tumor emboli and stromal area are higher than those in the CPTC area. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Correlation between macrophage density and clinicopathological features

The median number of lymphatic TAMs was used to divide the cases into two groups, and the correlation to clinicopathological features are listed in Table 3. The M2 (CD163-positive) TAM density was significantly associated with older age (p=0.024) and larger tumor size (p=0.022), whereas total (CD68-positive) TAM density was not significantly associated with any clinicopathological factors.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Clinicopathological Features

| |

Tumor CD68+ macrophages |

Tumor CD163+ macrophages |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=7) | High (n=7) | p | Low (n=7) | High (n=7) | p | |

| Age (years) | 31.6±8.3 | 39.3±18.4 | 0.333 | 27.0±8.5 | 43.9±14.4 | 0.024a |

| Sex | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Female | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.1±1.5 | 3.6±1.8 | 0.111 | 1.8±1.2 | 3.9±1.6 | 0.022a |

| T status | 0.266 | 0.266 | ||||

| T1+2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| T3+4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Pathological stage | 0.559 | 0.070 | ||||

| I+II | 6 | 4 | 7 | 3 | ||

| III+IV | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.462 | 0.462 | ||||

| Absent | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | ||

| Present | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Extrathyroid extension | 0.266 | 0.266 | ||||

| Absent | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Present | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Distant metastasis | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Absent | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Present | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

p<0.05.

TAMs and lymphatic invasion in DSV-PTC

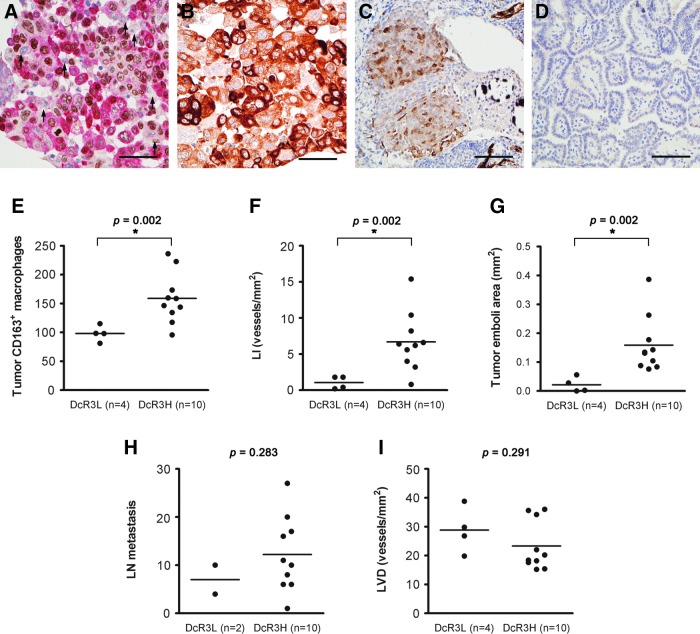

The increase in M2 TAMs was associated with an increase in lymphatic invasion (Fig. 3A) and size of tumor emboli (Fig. 3B), and to a lesser extent, LN metastases (Fig. 3C). LVD had an inverse relationship with the number of M2 TAMs (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Correlations between (A) lymphatic invasion index (LI), (B) tumor emboli area, (C) lymph node (LN) metastasis, and (D) lymphatic vessel density (LVD) with the density of CD163-positive macrophages. LI and tumor emboli area show a significant correlation with the density of CD163-positive macrophages (p<0.05).

DcR3 expression in DSV-PTC

Double staining for DcR3/TTF-1 indicated that DcR3 was exclusively expressed in DSV-PTC tumor cells and not in macrophages (Fig. 4A). In addition, the expression of DcR3 was confined to lymphatic tumor emboli (Fig. 4B) and tumor cells with squamous metaplasia (Fig. 4C), while CPTC (Fig. 4D) and nontumorous tissue was completely without expression. DcR3 expression was positively associated with M2 differentiation (Fig. 4D), lymphatic invasion (Fig. 4E), and size of emboli (Fig. 4F). A trend toward increased LN metastases (Fig. 4G) was also noted. However, LVD was lower in high DcR3-expressing tumors (Fig. 4H).

FIG. 4.

Decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) expression in DSV-PTC. (A) Representative photomicrograph of double staining for DcR3 and TTF-1 demonstrating that DcR3-positive cells (red) also show nuclear staining for TTF-1 (brown). Macrophages (arrows) are negative for both DcR3 and TTF-1 staining. The expression of DcR3 is (B) highest in the lymphatic tumor emboli, (C) mild to moderate in squamous metaplastic tumor cells, and (D) absent in CPTC (scale bars: 50 μm). Quantitative analyses of DcR3 expression in correlation with (E) CD163-positive macrophages, (F) LI, (G) tumor emboli area, (H) LN metastasis and (I) LVD. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy

Discussion

Extensive lymphatic invasion with dilated lymphatic spaces filled with PTC cells is a prominent feature in DSV-PTC, and it is often the predominant histopathological growth pattern. Our study shows that the lymphatic emboli in DSV-PTC are, in fact, a heterogeneous population, consisting of tumor cells and macrophages. Moreover, the majority of these TAMs expressed CD163, a well-established marker for M2-polarized macrophages (19,20). There was also a strong correlation between increased M2 TAMs and lymphatic invasion, suggesting that M2 TAMs have an important role in the process of lymphatic invasion. In addition, higher levels of M2 TAMs were strongly associated with older age and larger tumor size, with a trend toward a higher pathological stage. Finally, the preferential expression of DcR3 in tumor tissue was associated with higher levels of M2 TAMs and lymphatic invasion, suggesting that DcR3 may induce polarized macrophage differentiation toward the M2 phenotype, which, in turn, promotes lymphatic invasion.

M2 macrophages have poor antigen-presenting capability, produce factors that suppress T-cell proliferation and activity, and are better adapted at scavenging debris, promoting angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling. Recently, Wyckoff et al. (21) reported that an EGF-CSF1 macrophage-tumor cell paracrine interaction may facilitate blood vessel invasion in breast cancer. Although it is conceivable that similar mechanisms may be responsible for the dominant lymphatic invasion in DSV-PTC, further studies are needed to prove this.

Although DcR3 expression is found in many cancers (5,22–24), its role is not well understood. Recent studies have demonstrated that inflammation is a key factor in the induction of DcR3 expression, which was observed in epithelial cells in acute appendicitis (25) or Crohn's disease (26). In our study, DcR3 was expressed only in lymphatic tumor cells and squamous metaplastic tumor cells but not in macrophages and CPTC. We speculate that the inherent inflammatory microenvironment of DSV-PTC may be responsible for the induction of DcR3 expression in tumor cells. On the other hand, the lack of intimate contact between tumor cells and inflammatory cells in CPTC may explain the lack of DcR3 expression in CPTC tumor cells. Therefore, we further speculate that activation of the DcR3 gene may be a critical step in bridging the transformation from CPTC to DSV-PTC.

The major limitation of the current study is its shortage of DSV-PTC cases. As a result, certain clinicopathological parameters were not significantly correlated with tumor TAM density and DcR3 expression. Another limitation is the lack of long-term follow-up in some cases, which may have been the reason for lack of correlation between tumor TAM density and DcR3 expression with disease-free survival and overall survival of the patients. We anticipate that inclusion of additional cases and a longer follow-up time may produce more definitive results should these studies be performed.

In conclusion, our study revealed a close relationship between inflammation, DcR3 expression, M2 TAMs, and lymphatic invasion in DSV-PTC. Our results suggest that DcR3 may be a potential therapeutic target against lymphatic metastasis in this specific type of thyroid tumor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V98C1-047) and the National Science Council (NSC96-2628-B-075-003 and NSC99-2320-B-075-002). The authors also thank Hsui-Hsun Ma, Li-Rung Liao, and Chih-Yang Chiu from the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital for their technical assistance in immunohistochemistry studies.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Fukushima M. Ito Y. Hirokawa M. Akasu H. Shimizu K. Miyauchi A. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma in Japan: an 18-year experience at a single institution. World J Surg. 2009;33:958–962. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9940-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regalbuto C. Malandrino P. Tumminia A. Le Moli R. Vigneri R. Pezzino V. A diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: clinical, pathologic features, outcomes of 34 consecutive cases. Thyroid. 2011;21:383–389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma J. Liu L. Che G. Yu N. Dai F. You Z. The M1 form of tumor-associated macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer is positively associated with survival time. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohtaki Y. Ishii G. Nagai K. Ashimine S. Kuwata T. Hishida T. Nishimura M. Yoshida J. Takeyoshi I. Ochiai A. Stromal macrophage expressing CD204 is associated with tumor aggressiveness in lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1507–1515. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181eba692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang YC. Chen TC. Lee CT. Yang CY. Wang HW. Wang CC. Hsieh SL. Epigenetic control of MHC class II expression in tumor-associated macrophages by decoy receptor 3. Blood. 2008;111:5054–5063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurahara H. Shinchi H. Mataki Y. Maemura K. Noma H. Kubo F. Sakoda M. Ueno S. Natsugoe S. Takao S. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2011;167:e211–e219. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin JY. Li XY. Tadashi N. Dong P. Clinical significance of tumor-associated macrophage infiltration in supraglottic laryngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:280–286. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinosa I. Jose Carnicer M. Catasus L. Canet B. D'Angelo E. Zannoni GF. Prat J. Myometrial invasion and lymph node metastasis in endometrioid carcinomas: tumor-associated macrophages, microvessel density, and HIF1A have a crucial role. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1708–1714. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f32168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komohara Y. Hasita H. Ohnishi K. Fujiwara Y. Suzu S. Eto M. Takeya M. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic relevance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1424–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang JC. Chen JS. Lee CH. Chang JJ. Shieh YS. Intratumoral macrophage counts correlate with tumor progression in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:242–248. doi: 10.1002/jso.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niino D. Komohara Y. Murayama T. Aoki R. Kimura Y. Hashikawa K. Kiyasu J. Takeuchi M. Suefuji N. Sugita Y. Takeya M. Ohshima K. Ratio of M2 macrophage expression is closely associated with poor prognosis for Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) Pathol Int. 2010;60:278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steidl C. Lee T. Shah SP. Farinha P. Han G. Nayar T. Delaney A. Jones SJ. Iqbal J. Weisenburger DD. Bast MA. Rosenwald A. Muller-Hermelink HK. Rimsza LM. Campo E. Delabie J. Braziel RM. Cook JR. Tubbs RR. Jaffe ES. Lenz G. Connors JM. Staudt LM. Chan WC. Gascoyne RD. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryder M. Ghossein RA. Ricarte-Filho JC. Knauf JA. Fagin JA. Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:1069–1074. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caillou B. Talbot M. Weyemi U. Pioche-Durieu C. Al Ghuzlan A. Bidart JM. Chouaib S. Schlumberger M. Dupuy C. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) form an interconnected cellular supportive network in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YC. Hsu TL. Lin HH. Chio CC. Chiu AW. Chen NJ. Lin CH. Hsieh SL. Modulation of macrophage differentiation and activation by decoy receptor 3. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:486–494. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0903448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LiVolsi VA. Albores-Saavedra J. Asa SL. Papillary carcinoma. In: De Lellis RA, editor; Lloyd RV, editor; Heitz PU, editor; Eng C, editor. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Endocrine Organs. 3rd. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel S. Shah JP. Part II: Head and neck sites. In: Edge SB, editor; Byrd DR, editor; Carducci MA, editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper DS. Doherty GM. Haugen BR. Kloos RT. Lee SL. Mandel SJ. Mazzaferri EL. McIver B. Pacini F. Schlumberger M. Sherman SI. Steward DL. Tuttle RM. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau SK. Chu PG. Weiss LM. CD163: a specific marker of macrophages in paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:794–801. doi: 10.1309/QHD6-YFN8-1KQX-UUH6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TT. Schwartz EJ. West RB. Warnke RA. Arber DA. Natkunam Y. Expression of CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor) in normal tissues, lymphomas, carcinomas, and sarcomas is largely restricted to the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:617–624. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000157940.80538.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyckoff J. Wang W. Lin EY. Wang Y. Pixley F. Stanley ER. Graf T. Pollard JW. Segall J. Condeelis J. A paracrine loop between tumor cells, macrophages is required for tumor cell migration in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7022–7029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H. Zhang L. Lou H. Ding I. Kim S. Wang L. Huang J. Di Sant'Agnese PA. Lei JY. Overexpression of decoy receptor 3 in precancerous lesions and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:282–287. doi: 10.1309/XK59-4E4B-5WU8-2QR6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahama Y. Yamada Y. Emoto K. Fujimoto H. Takayama T. Ueno M. Uchida H. Hirao S. Mizuno T. Nakajima Y. The prognostic significance of overexpression of the decoy receptor for Fas ligand (DcR3) in patients with gastric carcinomas. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s101200200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macher-Goeppinger S. Aulmann S. Wagener N. Funke B. Tagscherer KE. Haferkamp A. Hohenfellner M. Kim S. Autschbach F. Schirmacher P. Roth W. Decoy receptor 3 is a prognostic factor in renal cell cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1049–1056. doi: 10.1593/neo.08626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S. Fotiadu A. Kotoula V. Increased expression of soluble decoy receptor 3 in acutely inflamed intestinal epithelia. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funke B. Autschbach F. Kim S. Lasitschka F. Strauch U. Rogler G. Gdynia G. Li L. Gretz N. Macher-Goeppinger S. Sido B. Schirmacher P. Meuer SC. Roth W. Functional characterisation of decoy receptor 3 in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2009;58:483–491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]