Summary

Background and objectives

Reports on the racial and ethnic differences in dialysis patient survival rates have been inconsistent. The literature suggests that these survival differences may be modified by age as well as categorizing white race as inclusive of Hispanic ethnicity. The goal of this study was to better understand these associations by examining survival among US dialysis patients by age, ethnicity, and race.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Between 1995 and 2009, 1,282,201 incident dialysis patients ages 18 years or older were identified in the United States Renal Data System. Dialysis survival was compared among non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics overall and stratified by seven age groups.

Results

The median duration of follow-up was 22.3 months. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, a lower mortality risk was seen in Hispanics in all age groups. Consequently, when Hispanic patients were excluded from the white race, the mortality rates in white race all increased. Using non-Hispanic whites as the reference, a significantly lower mortality risk for non-Hispanic blacks was consistently observed in all age groups above 30 years (unadjusted hazard ratios ranged from 0.70 to 0.87; all P<0.001). In the 18- to 30-years age group, there remained an increased mortality risk in blacks versus non-Hispanic whites after adjustment for case mix (adjusted hazard ratio=1.19, 95% confidence interval=1.13–1.25).

Conclusions

The mortality risk was lowest in Hispanics, intermediate in non-Hispanic blacks, and highest in non-Hispanic whites. This pattern generally holds in all age groups except for the 18- to 30-years group, where the adjusted mortality rate for non-Hispanic blacks exceeds the adjusted mortality rate of non-Hispanic whites.

Introduction

The survival advantage of black patients undergoing maintenance dialysis, the so-called survival paradox stemming from its opposite observation in the US general population, has been observed in most (1–6) but not all studies (7). Although black patients initiate maintenance dialysis at a younger age (4), they are less likely to receive kidney transplants, the treatment of choice in ESRD (8). In addition, when on dialysis, they are less likely to receive arteriovenous fistula placement (9) and adequate dialysis dose (10). Despite worse outcomes in these key clinical performance measures, black patients on dialysis had better survival than their white counterparts. Recent studies have suggested that the commonly cited survival advantage of black dialysis patients only applies to those patients older than 50 years (11). The reasons for these findings are unclear but may be related to several factors, including Hispanic whites being included in the white race reference group (12,13). Because Hispanic dialysis patients have lower mortality rates than non-Hispanic whites (14,15), it is unclear whether the apparent higher mortality rate for younger blacks relative to whites is a true phenomenon or caused by the inclusion of Hispanic patients in the reference cohort. Clarifying the nuances of the survival paradox in dialysis patients is crucial to advancing a more global understanding of key survival mediators in chronic medical conditions.

We, therefore, assessed the age-stratified survival rates of black patients compared with their white counterparts after excluding Hispanic patients from the reference group. Moreover, we sought to assess whether the survival advantage of Hispanic patients over non-Hispanic patients holds consistently across age groups.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research at the University of Virginia. We used the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) (15). We identified patients ages 18 years or older, either Caucasian/white or African American/black, with no prior kidney transplantation who initiated the first maintenance dialysis between January 1, 1995 and September 28, 2009. A total of 1,282,201 patients were included, of which 884,458 (69%) were white and 397,743 (31%) were black. We obtained the patients’ subsequent status of transplantation and death as well as demographic and clinical characteristics from the USRDS.

Study Variables

The survival difference among the racial/ethnic groups is of the primary interest. Survival time was calculated from the date of dialysis initiation to the earliest date of death, kidney transplant, or administrative end of study (September 28, 2009), with censoring at transplant or end of study.

Patient race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic [black and white]) was obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medical Evidence form (CMS-2728) (15). The 2005 form included changes in racial/ethnic classifications from the 1997 version. For ethnicity, the 1997 version allowed three options: non-Hispanic, Hispanic-Mexican, or Hispanic-other. We combined these two latter subdivisions into a single Hispanic category, which was consistent with the two options of non-Hispanic or Hispanic in the 2005 version. For race, both forms included white, black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. The 1997 version also allowed three additional designations of Indian Subcontinent, Mid-East/Arabian, and Other. We limited our assessment of racial designation to white and black/African American in the present report.

In the adjusted analyses of examining survival difference, the following covariates were included: age at ESRD onset, sex, insurance coverage at ESRD onset (private, Medicare, or Medicaid/none), body mass index, lifestyle behavior (smoking, alcohol, and drug dependence), immobility, cause of ESRD, dialysis type (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), and comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, cardiac failure, atherosclerotic heart diseases, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cancer) as well as pre-ESRD use of erythropoietin-stimulating agents.

Statistical Analyses

We compared dialysis survival among racial/ethnic subgroups using the Cox regression. We first examined such survival differences for the entire study cohort and then each of seven age groups (18–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71–80, and >80 years). The unadjusted racial/ethnic differences in survival were examined in Cox regression only with the race/ethnicity indicator variables. The adjusted survival differences included additional demographic and clinical covariates as described above and only patients who had complete data (95%). For each of these assessments, we performed two comparative analyses: one analysis using two race groups (black and white) with white race as the reference group, similar to the analysis performed in the work by Kucirka et al. (11), and one analysis using three distinct racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic) with the non-Hispanic white as the reference group.

We calculated mortality rate, expressed as the number of deaths per 100 patient-years, for each racial/ethnic subgroup to account for different patient-years of follow-up rather than the proportion of deaths because of the concern that the transplant (censoring) rates varied greatly among subgroups.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of 1,282,201 patients, 17.0% of whites versus only 1.9% of blacks were Hispanic. Hispanic patients accounted for 20.0% of patients with ages 18–30 years, 14.6% of patients with ages 31–50 years, and 11.7% of patients with ages >50 years. These Hispanic patients collectively formed the third race/ethnic group in the present study. In all age groups, Hispanic patients had the highest likelihood of being uninsured compared with the other two racial/ethnic groups. Compared across these three broader age groups, we noticed that some of the characteristics in the younger age groups exhibited a pattern that was opposite to the pattern in the older age groups. For example, in the age group of 18–30 years, 31.8% of Hispanic patients had GN as the cause of ESRD, representing the most prevalent form of kidney disease, compared with 23.0% of non-Hispanic blacks and 30.2% of non-Hispanic whites. At ages >50 years, GN was reported in only 3.9% of Hispanic patients, representing the group with the smallest percentage, with 4.2% of non-Hispanic blacks and 7.4% of non-Hispanic whites reported as having GN as the etiology of ESRD. By contrast, in the youngest group, only 14.7% of Hispanics had diabetes as a cause of ESRD compared with 17.3% of non-Hispanic blacks and 22.9% of non-Hispanic whites. In the age group >50 years, 67.6% of Hispanics had diabetes as the cause of ESRD compared with 50.2% of non-Hispanic blacks and 41.5% of non-Hispanic whites.

Table 1.

General patient characteristics by age and race/ethnicity

| Characteristics | Age=18–30 yr (n=42,083) | Age=31–50 yr (n=233,344) | Age>50 yr (n=1,006,774) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White n=15,706 (37.3%) | Non-Hispanic Black n=17,961 (42.7%) | Hispanic n=8416 (20.0%) | Non-Hispanic White n=95,583 (41.0%) | Non-Hispanic Black n=103,642 (44.4%) | Hispanic n=34,119 (14.6%) | Non-Hispanic White n=619,833 (61.6%) | Non-Hispanic Black n=268,621 (26.7%) | Hispanic n=118,320 (11.7%) | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 25.8±3.6 | 26.0±3.5 | 25.4±3.6 | 43.3±5.5 | 42.9±5.5 | 43.1±5.6 | 71.1±9.9 | 66.8±9.8 | 66.9±9.5 |

| Men (%) | 57.5 | 52.0 | 57.4 | 60.7 | 57.8 | 61.1 | 56.8 | 46.1 | 53.1 |

| No insurance (%) | 20.0 | 29.1 | 32.2 | 13.3 | 23.3 | 24.4 | 5.3 | 8.7 | 13.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.6±7.0 | 27.9±8.6 | 25.6±6.5 | 28.3±8.0 | 28.9±8.4 | 28.3±7.4 | 27.4±7.1 | 27.9±7.6 | 27.1±6.5 |

| Cause of ESRD | |||||||||

| GN (%) | 30.2 | 23.0 | 31.8 | 14.8 | 11.7 | 12.9 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| Diabetes (%) | 22.9 | 17.3 | 14.7 | 45.4 | 30.7 | 51.2 | 41.5 | 50.2 | 67.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 8.7 | 27.9 | 18.4 | 11.2 | 36.4 | 17.4 | 29.7 | 35.0 | 18.6 |

| Urologic (%) | 6.7 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Polycystic kidney (%) | 2.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Other (%) | 24.2 | 25.9 | 19.9 | 14.3 | 15.5 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 5.8 | 4.7 |

| Unknown (%) | 5.2 | 4.1 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 83.2 | 91.4 | 89.2 | 84.1 | 92.6 | 90.9 | 92.2 | 95.5 | 94.8 |

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Hypertension (%) | 65.5 | 75.1 | 69.2 | 73.7 | 80.9 | 79.1 | 76.8 | 84.4 | 81.3 |

| Diabetes (%) | 22.8 | 19.3 | 15.3 | 46.3 | 35.3 | 51.6 | 48.0 | 56.9 | 67.9 |

| Cardiac failure (%) | 6.9 | 9.8 | 6.8 | 16.6 | 18.3 | 16.5 | 39.9 | 33.5 | 34.1 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease (%) | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 11.7 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 35.7 | 20.2 | 24.6 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 8.9 | 4.7 | 7.4 | 19.3 | 12.2 | 15.6 |

Survival Difference between Black and White Patients—the Effect of Including or Excluding Hispanics

The median follow-up time was 22.3 months (range=1 day to 14.7 years), with an average mortality rate of 23.9 deaths per 100 patient-years. Table 2 presents the crude mortality rates, and Table 3 presents both unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of death in blacks versus whites overall and for seven age groups. In Tables 2 and 3, the results of using the three racial/ethnic groups are presented on the right, whereas the results of using the two race groups are on the left.

Table 2.

Unadjusted mortality rates by race/ethnicity in the overall and seven age groups

| Race Including Hispanic Ethnicity | Race Excluding Hispanic Ethnicity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two Race Groups | Patient-Years at Risk | Number of Deaths (%) | Mortality Rate (Deaths per 100 Patient-Years)a | Three Racial/Ethnic Groups | Patient-Years at Risk | Number of Deaths (%) | Mortality Rate (Deaths per 100 Patient-Years)a |

| Overall | 3,340,692 | 799,777 (62.4) | 23.9 | ||||

| White | 2,072,046 | 572,486 (64.7) | 27.6 | Non-Hispanic white | 1,622,216 | 493,873 (67.6) | 30.4 |

| Black | 1,268,646 | 227,291 (57.1) | 17.9 | Non-Hispanic black | 1,245,312 | 222,936 (57.1) | 17.9 |

| Hispanic | 473,163 | 82,968 (51.6) | 17.5 | ||||

| Age=18–30 yr (3.3%) | |||||||

| White | 68,870 | 3700 (15.6) | 5.4 | Non-Hispanic white | 40,582 | 2795 (17.8) | 6.9 |

| Black | 72,249 | 5079 (27.7) | 7.0 | Non-Hispanic black | 70,994 | 5012 (27.9) | 7.1 |

| Hispanic | 29,543 | 972 (11.5) | 3.3 | ||||

| Age=31–40 yr (6.2%) | |||||||

| White | 121,803 | 12,180 (28.9) | 10.0 | Non-Hispanic white | 84,089 | 9681 (31.2) | 11.5 |

| Black | 149,047 | 14,070 (37.5) | 9.4 | Non-Hispanic black | 146,611 | 13,844 (37.5) | 9.4 |

| Hispanic | 40,150 | 2725 (23.4) | 6.8 | ||||

| Age=41–50 yr (12.0%) | |||||||

| White | 249,534 | 34,590 (40.3) | 13.9 | Non-Hispanic white | 176,384 | 27,352 (42.4) | 15.5 |

| Black | 256,118 | 30,513 (44.9) | 11.9 | Non-Hispanic black | 251,712 | 29,995 (44.9) | 11.9 |

| Hispanic | 77,555 | 7756 (34.5) | 10.0 | ||||

| Age=51–60 yr (19.0%) | |||||||

| White | 417,644 | 80,401 (52.6) | 19.3 | Non-Hispanic white | 302,268 | 64,196 (54.7) | 21.2 |

| Black | 306,864 | 46,859 (51.7) | 15.3 | Non-Hispanic black | 301,372 | 45,959 (51.6) | 15.2 |

| Hispanic | 120,868 | 17,105 (46.0) | 14.2 | ||||

| Age=61–70 yr (23.9%) | |||||||

| White | 533,647 | 146,920 (68.1) | 27.5 | Non-Hispanic white | 418,774 | 123,091 (69.8) | 29.4 |

| Black | 278,780 | 59,068 (64.9) | 21.2 | Non-Hispanic black | 272,866 | 57,773 (64.9) | 21.2 |

| Hispanic | 120,788 | 25,124 (60.7) | 20.8 | ||||

| Age=71–80 yr (24.4%) | |||||||

| White | 503,834 | 195,595 (79.8) | 38.8 | Non-Hispanic white | 438,613 | 175,206 (80.9) | 39.9 |

| Black | 163,241 | 51,098 (76.0) | 31.3 | Non-Hispanic black | 160,121 | 50,117 (76.0) | 31.3 |

| Hispanic | 68,341 | 21,370 (72.0) | 31.3 | ||||

| Age>80 yr (11.2%) | |||||||

| White | 176,713 | 99,100 (83.3) | 56.1 | Non-Hispanic white | 161,505 | 91,552 (83.7) | 56.7 |

| Black | 42,346 | 20,604 (82.1) | 48.7 | Non-Hispanic black | 41,636 | 20,236 (82.1) | 48.6 |

| Hispanic | 15,918 | 7,916 (78.7) | 49.7 | ||||

Number of deaths/patient-years at risk×100.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios of death for all blacks compared with all whites and for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites in the overall and seven age groups

| Age (yr) | Reference: All Whites Including Hispanics | Reference: Non-Hispanic Whites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | |||

| Overall | Black | 0.66 (0.65–0.66) | 0.83 (0.83–0.84) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.60 (0.59–0.60) | 0.77 (0.76–0.77) |

| Hispanic | 0.58 (0.58–0.59) | 0.70 (0.69–0.70) | ||||

| 18–30 | Black | 1.33 (1.27–1.39) | 1.43 (1.37–1.50) | Non-Hispanic black | 1.04 (0.99–1.09)b | 1.19 (1.13–1.25) |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) | 0.58 (0.53–0.62) | ||||

| 31–40 | Black | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.82 (0.80–0.84) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00)b |

| Hispanic | 0.59 (0.57–0.62) | 0.67 (0.64–0.70) | ||||

| 41–50 | Black | 0.85 (0.83–0.86) | 0.90 (0.89–0.92) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.75 (0.74–0.77) | 0.78 (0.77–0.80) |

| Hispanic | 0.64 (0.62–0.66) | 0.61 (0.60–0.63) | ||||

| 51–60 | Black | 0.78 (0.77–0.79) | 0.82 (0.81–0.83) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.70 (0.69–0.71) | 0.72 (0.71–0.73) |

| Hispanic | 0.66 (0.65–0.67) | 0.64 (0.63–0.65) | ||||

| 61–70 | Black | 0.77 (0.76–0.77) | 0.80 (0.80–0.81) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.72 (0.71–0.72) | 0.74 (0.73–0.75) |

| Hispanic | 0.71 (0.70–0.72) | 0.71 (0.70–0.72) | ||||

| 71–80 | Black | 0.81 (0.80–0.82) | 0.83 (0.83–0.84) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.79 (0.78–0.80) | 0.80 (0.79–0.81) |

| Hispanic | 0.79 (0.78–0.80) | 0.79 (0.77–0.80) | ||||

| >80 | Black | 0.88 (0.87–0.89) | 0.87 (0.86–0.88) | Non-Hispanic black | 0.87 (0.86–0.88) | 0.85 (0.84–0.87) |

| Hispanic | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) | ||||

All P values<0.001 unless otherwise specified. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex, insurance type (private, Medicare, or Medicaid/none), body mass index, lifestyle behavior, immobility, cause of ESRD, dialysis type, pre-ESRD use of erythropoietin-stimulating agents, and comorbid conditions.

P=0.08.

Overall, non-Hispanic white patients had a substantially higher mortality rate than non-Hispanic black or Hispanic patients (30.4 versus 17.9 or 17.5 deaths per 100 patient-years) (Table 2). In the overall population as well as all seven age groups, mortality rates of non-Hispanic whites were consistently higher than all whites, including Hispanics, whereas the mortality rates of non-Hispanic blacks were similar to the rates of all blacks. As an example, in the age group of 18–30 years, the mortality rate (deaths per 100 patient-years) was 6.9 in non-Hispanic whites and reduced to 5.4 in all whites including Hispanics, whereas the mortality rate was similar for non-Hispanic blacks and all blacks (7.1 versus 7.0).

Consequently, the HRs of blacks, relative to non-Hispanic whites, were all reduced from the HRs when Hispanic white patients were included in the white population (Table 3). Using non-Hispanic whites as the reference group, the mortality risk for non-Hispanic blacks was consistently lower in all age groups above 30 years. In the age group of 18–30 years that currently accounts for 3.3% of all dialysis patients, there remained an increased mortality risk in non-Hispanic blacks versus non-Hispanic whites after adjustment for case mix; unadjusted HR (95% confidence interval) was 1.04 (0.99–1.09), P=0.08, and adjusted HR was 1.19 (1.13–1.25), P<0.001 (Table 3). These HRs were, however, markedly attenuated from the HRs of 1.33 and 1.43, respectively, where blacks were compared with all whites, including Hispanics, in this youngest group.

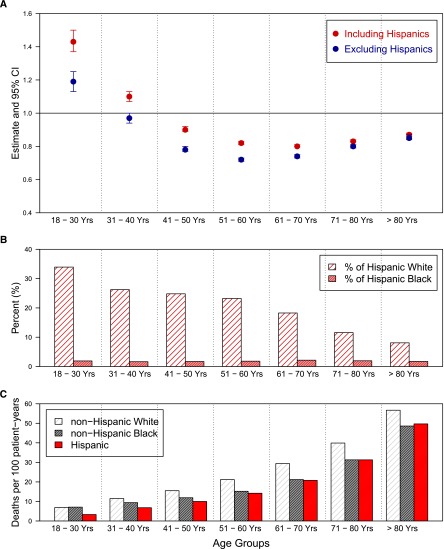

Excluding Hispanic whites in the reference group had a larger impact on the survival comparison between blacks and whites in the younger age groups than the older age groups. As seen in Figure 1A, there was a substantial reduction in the HRs of blacks versus whites in the younger age groups after excluding Hispanic whites from the reference group. Two factors accounted for this difference. One factor is that the younger groups consisted of larger proportions of Hispanic whites than the older groups (Figure 1B). From younger to older age groups, the percentage of Hispanics in white patients decreased sequentially from 33.9% to 26.2% to 24.8% to 23.2% to 18.3% to 11.6% to 8.1%, whereas in black patients, the percentage of Hispanics was much lower, ranging from 1.6% to 2.2%. The second factor was that the mortality rates of the Hispanic patients relative to the non-Hispanic whites were much lower in the younger age groups than in the older age groups (Figure 1C). In the age group of 18–30 years, the mortality rate (per 100 patient-years) of Hispanic patients was 3.3, which was 52% lower than the mortality rate of the non-Hispanic whites of 6.9. In contrast, the mortality rate of Hispanic patients in the age group of >80 years was 49.7, only 10% lower than the mortality rate of non-Hispanic whites of 56.7.

Figure 1.

Relationship of age, race, and ethnicity and dialysis survival. (A) Adjusted hazard ratio of death when all black patients were compared with all white patients (red) and adjusted hazard ratio of death when non-Hispanic blacks were compared with non-Hispanic whites (blue) by age group. (B) Percent of white and black patients who identified as Hispanic by age group. (C) Unadjusted mortality rate (deaths per 100 patient-year) of non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic patients by age group.

Survival Advantage of Hispanic Patients over Non-Hispanic White Patients

As shown in Figure 1C and Tables 2 and 3, the mortality rates among Hispanic patients were consistently lower than the mortality rates of non-Hispanic whites in all age groups. This survival advantage was more substantial in the younger than older age groups. The unadjusted HR (95% confidence interval) of Hispanics versus non-Hispanic whites was 0.48 (0.45–0.52) in the age group of 18–30 years compared with 0.88 (0.86–0.90) in the age group of >80 years. A similar pattern was seen in the adjusted HRs.

Survival Difference between Hispanic Patients and Non-Hispanic Black Patients

Overall, Hispanic patients and non-Hispanic black patients had similar mortality rates (17.5 versus 17.9 per 100 patient-years) (Table 2). However, in younger age groups, Hispanic patients had much lower mortality risks than their non-Hispanic black counterparts. In the age group of 18–30 years, the mortality rates (per 100 patient-years) were 3.3 and 7.1 in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic black groups, respectively. In contrast, the mortality rates were 20.8 and 21.2 in the age group of 61–70 years for Hispanic and non-Hispanic black groups, respectively (Figure 1C and Table 2).

Discussion

In the general US population, blacks have an estimated lifespan that is 4–5 years less than the estimated lifespan of their white counterparts (16), probably because of poorer access to health care, cultural differences in health beliefs and behaviors, disadvantaged socioeconomic status, and/or genetic influences on the development and progression of key medical conditions (17–21). Given this background, the apparent paradoxically longer survival for blacks on maintenance dialysis compared with whites is even more astounding (1–6). However, this finding has not been consistent. Robinson et al. (7) performed a cohort analysis of 6677 patients between 1996 and 2001 in the American arm of the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study and found no racial/ethnic differences in adjusted mortality rates (7). Their findings may be explained by a shorter median follow-up time of 15.3 months compared with 22.3 months in our study and a sample size that was only 0.5% of our cohort. Kucirka et al. (11) reported a survival advantage in blacks compared with whites but found that it was limited to older patients, whereas blacks under 50 years of age had two times the risk of death compared with their white counterparts. The findings of Kucirka et al. (11) of such a strong influence of age on the black–white mortality differences may be related to heterogeneity in the white cohort in their analysis produced by combining Hispanics and non-Hispanics (12,13).

In our analyses of the national USRDS database, the apparent shorter survival in younger black patients relative to their white counterparts was not observed without the inclusion of younger Hispanics, who had lower mortality rates, in the white population, except for the youngest age group of 18–30 years. For this small youngest-age subpopulation, when Hispanics were excluded from the white race reference group, a higher adjusted mortality risk for blacks versus non-Hispanic whites was noted, although markedly attenuated compared with the study by Kucirka et al. (11). In fact, the mortality rates in blacks were lower than the rates in the non-Hispanic whites for all age groups above 30 years, and only in the age group of 18–30 years did the adjusted mortality rate for blacks exceed the adjusted mortality rate for non-Hispanic whites. Therefore, in our analyses, the commonly cited survival advantage of black patients over non-Hispanic whites holds in most age groups.

The underlying reasons for the reduced mortality, especially in older black dialysis patients, remain poorly defined but may include improved access to health care as a result of Medicare eligibility, survival bias (22,23), access to transplantation (8), cultural differences in adaptation to chronic illness (24), more favorable nutritional and anthropometric profile (25,26), differential response to inflammation (27), more common treatment with active vitamin D (28,29), differential thresholds for dialysis adequacy (10), and a differing cardiovascular risk profile including higher BPs, which may paradoxically have a beneficial association with survival in ESRD patients (5). There may also be other unmeasured factors, such as environmental exposures, markers of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and/or selected genetic polymorphisms, that could influence disease progression and/or risk of death across subgroups (30). Finally, many studies suggest that blacks receive less pre-ESRD care (9,15), which could lead to a survivorship bias in ESRD.

By contrast, the higher adjusted mortality rates for blacks compared with non-Hispanic whites in the age group of 18–30 years may be related to a higher background of noncardiovascular events with greater mortality rates from homicide and motor vehicle accident, lower likelihood of being insured, limited social support networks, and lack of trust in medical systems that may reduce their access to medical care, which collectively eliminate the survival advantage of older black dialysis patients (12).

Early studies have shown that Hispanic patients had better survival than non-Hispanic patients (14). This issue has gained prominence in recent years with the rapid growth of the Hispanic dialysis population in the United States. Currently, Hispanics account for nearly 20% of all dialysis patients and up to 35% in younger age groups. The present analysis is the first national study that examined the effect modification by age on the survival differences in dialysis patients based on the inclusion or exclusion of Hispanics in the black and white subgroups. Using data over 15 years and adjusting for multiple domains of patient covariates, we confirmed that there was, indeed, a substantial survival advantage of Hispanic patients over non-Hispanic whites in the overall dialysis population. Moreover, this survival advantage could be seen consistently in all age groups (Figure 1C and Table 3).

Although Hispanic patients have no particular advantage in access to clinical care (3,15,31,32) and have the lowest rates of health insurance in the United States (Table 1) (33), they exhibited the best dialysis survival. Inasmuch as Hispanics have their unique culture, health risk factors, and health outcomes, it would be particularly important to distinguish Hispanic whites from non-Hispanics whites in contemporary racial/ethnic disparity research. Considering Hispanic patients as a separate race/ethnicity group whenever possible should greatly enhance the understanding of key mediators underlying racial/ethnic disparities in health care delivery and health outcomes.

Because our objective was to examine the association of race and ethnicity with survival on dialysis, we used the Cox regression with the cause-specific hazard method, in which the transplants were treated as censored observations. Here, the estimated cause-specific hazards for death might have been biased by censoring generally healthier transplant patients. However, the bias is not expected to be large, because the patient covariates were included and controlled. The subdistribution hazard method of Fine and Gray (34) is also available for competing-risk data, but it does not address the question of our interest. In the subdistribution hazard method in which dialysis patients receiving transplants are treated as immortal when calculating the hazard on death, the higher transplant rate for whites confers a lower probability of observing death before transplant in the white population, hence producing apparent larger HRs for blacks versus whites for mortality. However, these larger HRs heavily reflect differences in transplant rates between white and black races, not the implication of race for mortality while patients remain on dialysis.

The present findings should be viewed with some limitations. First, the study population excluded patients who died before the initiation of dialysis. Thus, it is unclear if the differences in survival patterns found among the three racial/ethnic groups also apply to nondialysis-dependent CKD patients and how a pre-ESRD survival bias may influence our findings. Second, misreporting of covariate data, including race and ethnicity, and comorbid conditions may be present in the administrative database. Patient variables, such as detailed clinical assessment (e.g., inflammatory markers and nutritional profile), education attainment and income, and ESRD quality performance measures such as anemia, vascular access, hospitalization rates, and other factors that could affect mortality risks, were not controlled, because these data are not available in large administrative databases. Finally, the option of selecting Indian Subcontinent, Mid-East/Arabian, or Other on the 1997 Medical Evidence form may not have been evenly distributed across the more limited options after 2005. However, it is unlikely that any redistribution of this small cohort would significantly affect our results.

In summary, we have shown that, among racial/ethnic subgroups of maintenance dialysis patients, the mortality risk was lowest in Hispanics, intermediate in non-Hispanic blacks, and highest in non-Hispanic whites. This pattern holds in the overall dialysis population and all age groups, except for the youngest group (18–30 years), where there is a higher adjusted mortality risk for non-Hispanic blacks compared with non-Hispanic whites. Continued effort to discern the factors responsible for the general survival advantage of black and Hispanic patients may yield major clinical and public health implications for the US ESRD and potentially, CKD populations.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant 5R01DK084200-02. In addition, K.C.N. is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants U54MD007598, UL1TR000124, P30AG021684, and P20-MD000182.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the staff at the United States Renal Data System for their assistance in providing data.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Held PJ, Pauly MV, Diamond L: Survival analysis of patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA 257: 645–650, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agodoa L, Eggers P: Racial and ethnic disparities in end-stage kidney failure-survival paradoxes in African-Americans. Semin Dial 20: 577–585, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris KC, Agodoa LY: Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int 68: 914–924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Derose SF, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC: Racial and survival paradoxes in chronic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 493–506, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powe NR: To have and have not: Health and health care disparities in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 64: 763–772, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson BM, Joffe MM, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Feldman HI: Revisiting survival differences by race and ethnicity among hemodialysis patients: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2910–2918, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM: Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 743–751, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasse H, Hopson SD, McClellan W: Racial and gender differences in arteriovenous fistula use among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 32: 234–241, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen WF, Jr, Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Lowrie EG: Dose of hemodialysis and survival: Differences by race and sex. JAMA 280: 1764–1768, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, Hall EC, James N, Massie AB, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA 306: 620–626, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Norris KC: Racial survival paradox of dialysis patients: Robust and resilient. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 182–185, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streja E, Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP: Race, age, and mortality among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA 306: 2215, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankenfield DL, Rocco MV, Roman SH, McClellan WM: Survival advantage for adult Hispanic hemodialysis patients? Findings from the end-stage renal disease clinical performance measures project. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 180–186, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Miniño AM, Kung HC: Deaths: Final Data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_03.pdf Accessed November 10, 2012 [PubMed]

- 17.Powe NR: Let’s get serious about racial and ethnic disparities. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1271–1275, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Institute of Medicine : (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC: Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ Health Perspect 112: 1645–1653, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, Tomijima N, Bulzacchelli MT, Iandiorio TJ, Ezzati M: Eight Americas: Investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 3: e260, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL: Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med 347: 1585–1592, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Adler S, Norris K: Racial differences in mortality among those with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1403–1410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Golan E, Shohat T, Streja E, Norris KC, Kopple JD: Survival disparities within American and Israeli dialysis populations: Learning from similarities and distinctions across race and ethnicity. Semin Dial 23: 586–594, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris KC, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD: The role of race in survival among patients undergoing dialysis. Nephrol News Issues 25: 13–14, 16, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Molnar MZ, Norris KC, Greenland S, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Role of nutritional status and inflammation in higher survival of African American and Hispanic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 883–893, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC: Is the malnutrition-inflammation complex the secret behind greater survival of African-American dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2150–2152, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crews DC, Sozio SM, Liu Y, Coresh J, Powe NR: Inflammation and the paradox of racial differences in dialysis survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2279–2286, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Ricks J, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Greenland S, Norris KC: Impact of race on hyperparathyroidism, mineral disarrays, administered vitamin D mimetic, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Bone Miner Res 25: 2724–2734, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf M, Betancourt J, Chang Y, Shah A, Teng M, Tamez H, Gutierrez O, Camargo CA, Jr, Melamed M, Norris K, Stampfer MJ, Powe NR, Thadhani R: Impact of activated vitamin D and race on survival among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1379–1388, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norris K, Nissenson AR: Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1261–1270, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Kimmel PL, Palevsky PM, Fine MJ: Associations of race and ethnicity with anemia management among patients initiating renal replacement therapy. J Natl Med Assoc 99: 1218–1226, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arce CM, Mitani AA, Goldstein BA, Winkelmayer WC: Hispanic ethnicity and vascular access use in patients initiating hemodialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 289–296, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Kaiser Family Foundation: Uninsured Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity, States (2009–2010), US, 2010. Available at: http://statehealthfacts.org/comparetable.jsp?ind=143&cat=3 Accessed August 19, 2012

- 34.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]