Abstract

The connection between the Hedgehog pathway and cholesterol has been recognized since the early days that shaped our current understanding of this unique pathway. Cholesterol and related lipids are intricately linked to HH signaling: from the role of cholesterol in HH biosynthesis to the modulation of HH signal reception and transduction by other sterols, passing by the phylogenetic relationships among many components of the HH pathway that resemble or contain lipid-binding domains. Here I review the connections between HH signaling, cholesterol and its derivatives and analyze the potential implications for HH-dependent cancers.

Hedgehog signaling overview

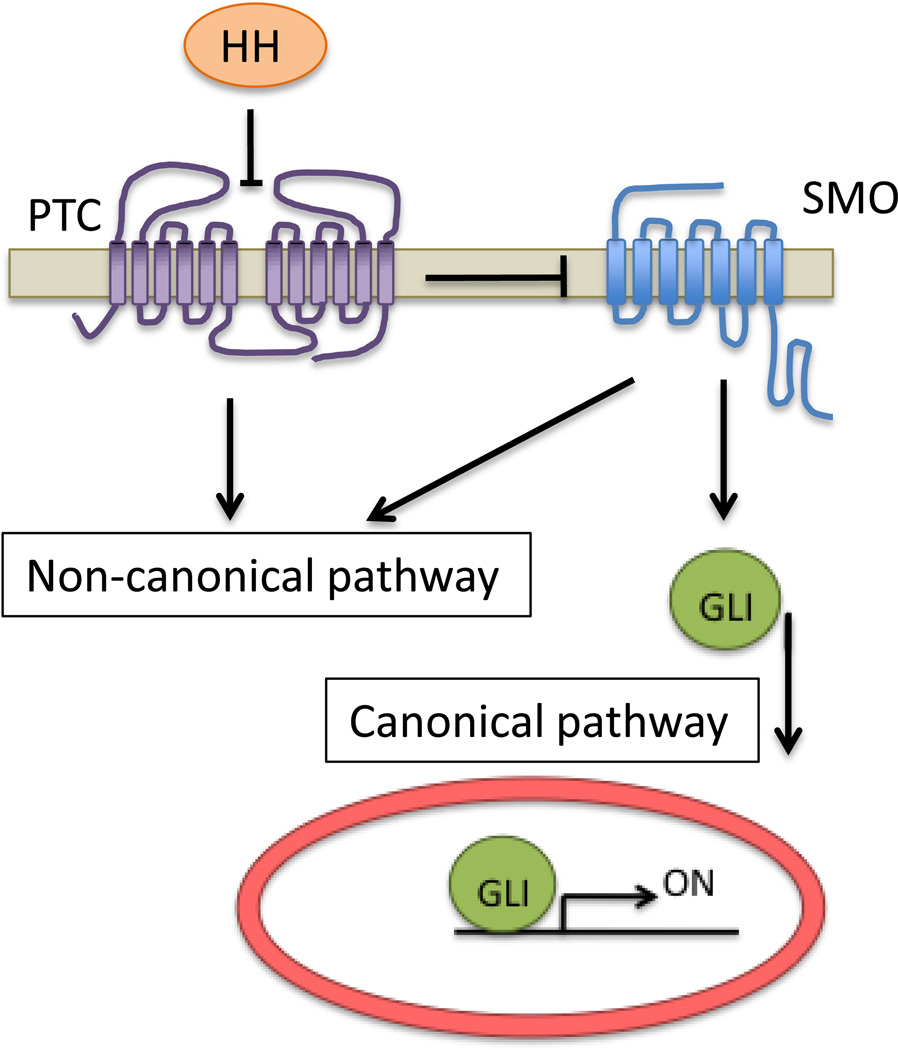

Hedgehog (HH) proteins promote specification, proliferation, differentiation and migration in a variety of cell types. The three HH isoforms, Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), Indian Hedgehog (IHH), and Desert Hedgehog (DHH), act on a 12-transmembrane tumor suppressor receptor Patched1 (PTC1) (Figure 1) [1]. A second receptor isoform, PTC2, appears to be less relevant in cancer, increasing tumor susceptibility only in a PTC1 heterozygote background [2]. Binding of PTC1 results in de-repression of the oncogene Smoothened (SMO), a 7-transmembrane Gi protein-coupled receptor [3,4], by means of phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subcellular localization changes [5–7]. Active SMO prevents degradation and promotes activation of the GLI family of transcription factors that mediate HH transcriptional responses [1]. Novel HH functions that are not exerted by GLIs and which are termed “non canonical” have been discovered in the last years and are reviewed elsewhere [8].

Figure 1.

Overview of the HH signaling network. HH signaling is initiated upon binding of a HH protein to its receptor PTC, which de-represses SMO. In the canonical pathway, SMO activation leads to increased transcriptional activity of the GLI family of transcription factors. GLI-independent actions of PTC and SMO are collectively known as “non-canonical” signaling.

Hedgehog in cancer development and maintenance

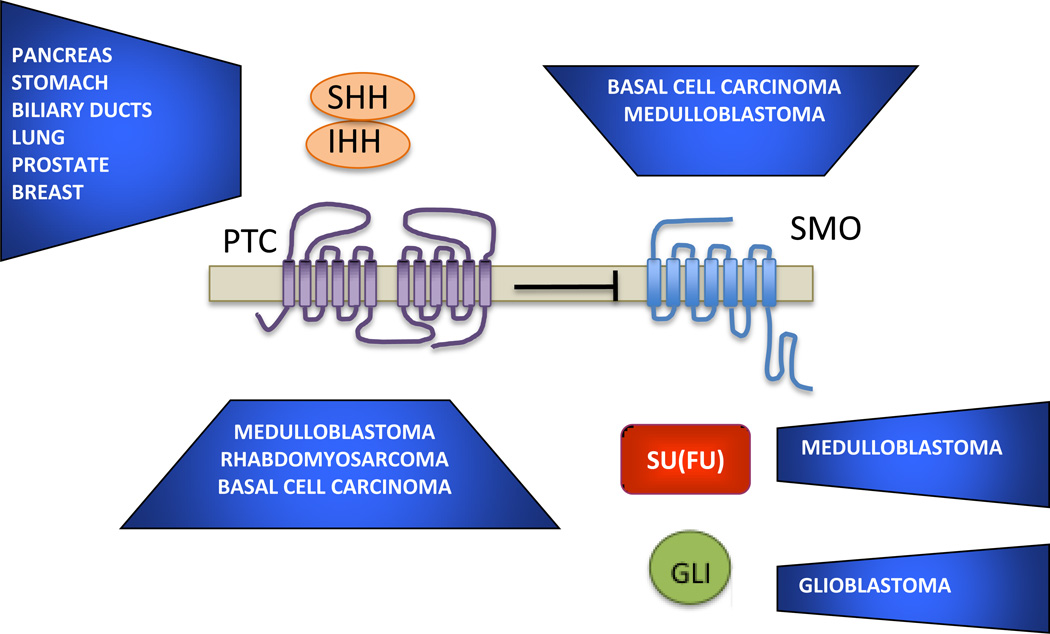

HH proteins control cell growth, survival and differentiation in a cell type-specific manner and by different mechanisms. HH signaling directly regulates proliferation of cerebellar granule precursors and epidermal basal stem cells [9,10] and indirectly supports other cell types by stimulating angiogenesis [11, 12]. Functional heterozygosity for PTC1 is the cause of Gorlin’s syndrome, characterized by high incidence of the triad basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the skin, medulloblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma upon somatic inactivation of the wild type PTC1 allele [13, 14]. Sporadic loss-of-function mutations of PTC1 and of Suppressor of Fused (SUFU), an intracellular negative regulator of GLI activity, are strongly associated with medulloblastoma and BCC [15–19] (Figure 2). Similarly, gain-of-function mutations of SMO that render it insensitive to inhibition by PTC1 are usually found in the same types of cancers, in which constitutive, ligand-independent activation of the HH pathway occurs in a cell autonomous manner [20, 21]. Other cancer types, mostly epithelial, are characterized by overexpression of SHH and IHH which act in autocrine (small cell lung cancer, some GI tract cancers) or paracrine ways with the stroma (pancreatic, prostate adenocarcinoma) creating a tumor favorable environment [22–25]. Yet other cancer types are dependent on stroma production of HH ligands for survival, as is the case of B-cell lymphoma [26]. A hallmark of all these cancer types is the activation of GLI target genes, chief among them GLI1 and PTC1, which are used as readouts of HH signaling activity. However, the contribution of non-canonical HH signaling in tumor progression as an anti-apoptotic and pro-angiogenic factor is starting to be appreciated despite being more difficult to study due to the lack of specific readouts [25, 27].

Figure 2.

Summary of association of genetic alterations of the HH pathway and cancer type. In the case of SHH and IHH is by overexpression without any reported mutations, for PTC1 and SU(FU) the defect is deficiency or loss-of-function mutations, for SMO is gain-of-function mutations and for GLI is gene amplification.

Cholesterol in Hedgehog processing, diffusion, and reception

The role of cholesterol in the HH pathway was early recognized since active HH proteins are covalently modified with cholesterol, making this post-translational modification unique among all known proteins [28]. HHs are synthesized as ~49 KDa precursors which undergo a first signal peptide cleavage upon entering the ER. Then the C-terminal domain of HHs catalyzes an intramolecular splicing reaction that is resolved by addition of cholesterol to a cysteine in the newly created C-terminus. The cholesterol modified N-terminal fragment is further palmitoylated at the N-terminus producing a highly hydrophobic, high activity protein [29]. Cholesterol is absolutely necessary to carry on this cleavage and to yield a protein with a low diffusion rate whose gradients are finely regulated during embryogenesis. Lipid-modified HH proteins remain associated to the plasma membrane upon secretion in the absence of the 12-TM proteins Dispatched A and B, homologous to PTC1, which contain a Sterol Sensing Domain (SSD) [30, 31]. In the current model Dispatched proteins induce HH release from the membrane allowing the formation of different diffusible forms of HH. Water-soluble HHs have been found as part of a multimeric complex with the hydrophilic residues making a shell for the hydrophobic lipid core, but also associated to lipoprotein particles [32, 33]. In humans there is evidence that a small amount of IHH is present in a lipoprotein fraction [34]. Perhaps more relevant, SHH has been detected in exosomes or microparticles that promote angiogenesis [35]. While the role of cholesterol in processing and trafficking of HHs is well established, a recent study suggests that it may not be absolutely required for activity. A collaborative effort among several HH groups demonstrated that HH precursor is fully active in cell culture and, therefore, the role of cholesterol appears to be more important for the establishments of developmental gradients than for homeostasis in adult organisms [36].

Lipid-modified active HH proteins are not soluble in aqueous solutions, yet they signal at a distance from their source. In Drosophila, the single HH isoform is found associated with lipoprotein-like macromolecular complexes called lipophorins and reduction of lipophorin levels results in accumulation of HH near its source and impaired signaling at a distance [33]. Remarkably, Drosophila PTC not only binds its cognate ligand HH, but also acts as a Lipophorin receptor to promote its endocytosis and to regulate intracellular lipid homeostasis [37]. This study confirmed that lipoproteins have a role in HH distribution and gradient formation but are not required for signal transduction. These findings promoted the search for the presence of HH in human serum lipoproteins. IHH, but not SHH or DHH, was detected in the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) fraction of human serum [34]. While this fraction of IHH is not accessible to tissues, VLDL increased survival of endothelial cells, which are exquisitely dependent on HH ligands for survival [12], suggesting that this circulating pool of HH could have a role in tumor angiogenesis.

Another enigmatic piece of the lipid-HH puzzle is that the LDL receptor family member LRP2, also known as megalin, is specifically required as a SHH co-receptor with PTC1 during early forebrain specification and its deficiency results in holoprosencephaly phenotypes [38, 39]. It is noteworthy to mention the similarities between the HH and Wnt signaling pathways, both utilizing a 7-TM protein of the same GPCR subtype, and both having in some circumstances an LRP co-receptor, which in the case of Frizzleds is LRP-5 or LRP-6 [40].

Since HH proteins are modified with cholesterol, it is not surprising that PTC1 can bind to cholesterol and can promote the efflux of the fluorescent cholesterol derivative BODIPY-cholesterol, speculatively through its sterol-sensing domain, when overexpressed in a heterologous system [41]. However, binding of HHs to PTC1 does not involve the cholesterol moiety; indeed cholesterol-free HH displays high affinity [42]. It seems that binding of HH proteins to PTC1 inhibits its ability to promote cholesterol efflux and elevates intracellular cholesterol [41]. The use of a cholesterol synthesis inhibitor, lovastatin, prevented activation of the canonical HH pathway by SHH, suggesting that accumulation of intracellular cholesterol is necessary but not sufficient for HH signal transduction. Addition of cholesterol alone stimulated SMO accumulation at the plasma membrane, the first step in SMO activation.

Sterols that regulate Smoothened activity

The mechanism of SMO activation when HH proteins bind to PTC1 remains elusive. PTC1 acts catalytically to inhibit SMO through a mediator molecule, which was postulated to be a lipid given the homology of PTC1 with bacterial permeases of the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family that transport lipophilic toxins [43, 44]. Consistent with this notion it was proposed that PTC1 activity either increases the concentration of an inhibitor of SMO or decreases the level of a SMO agonist. Some oxysterols (OHC), oxygenated derivatives of cholesterol, can bind to SMO cooperatively with two well-known agonists, purmorphamine and SAG, in a site distinct from the binding pocket of the inhibitor cyclopamine [45]. The endogenous side-chain oxysterols 20(S)-OHC and 25(S)-OHC, but not oxysterols in position 7 (B ring), activate SMO at low micromolar concentrations, and inhibition of their biosynthetic pathway at different steps using simvastatin, zaragozic acid, ketoconazol or triparanol inhibits HH signaling and proliferation in medulloblastoma cells and fibroblasts [45–47]. Moreover, the effect of these compounds on the Hh pathway is highly stereo-selective, with the S-configuration of 20-OHC and 25-OHC being the only active epimer for SMO activation [45].

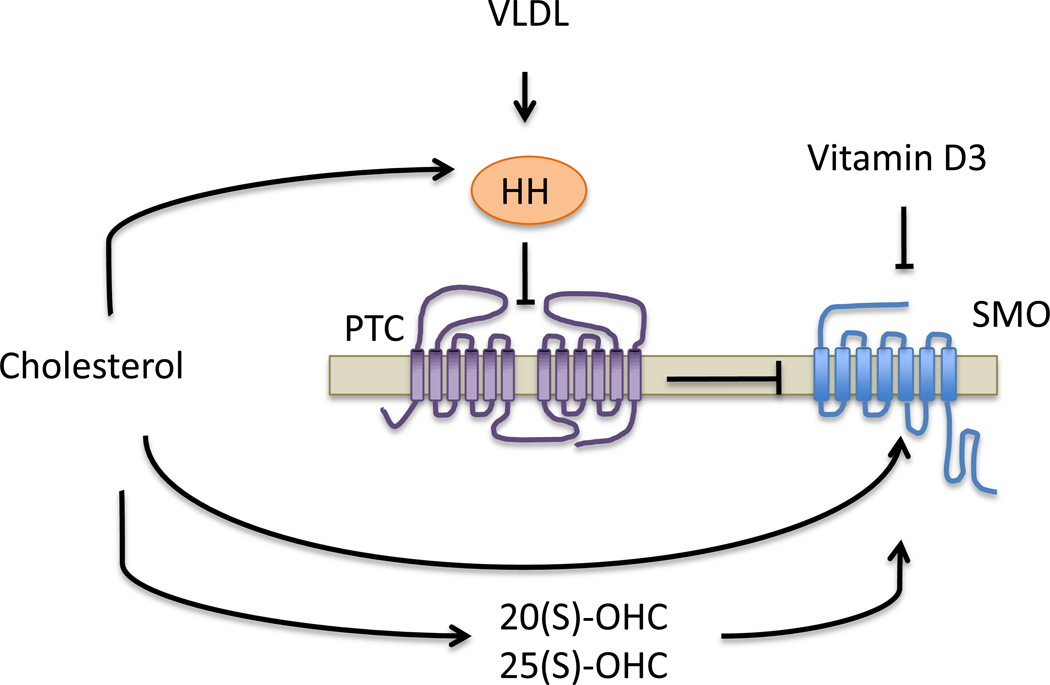

Numerous evidences indicate that PTC1 represses SMO in a cell autonomous fashion. However, Biljsma et al. challenged the dogma by reporting that PTC1 increases the secretion of pro-vitamin D3 and that this compound or a derived metabolite has the capacity to inhibit SMO non-cell autonomously [48]. A summary of the known role of sterol-like compounds on the membrane components of the HH pathway is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Role of cholesterol and its derivatives in the HH pathway. Arrows indicate positive interactions, stopped lines indicate inhibition of the component.

Targeting Hedgehog in cancer through sterol modulation

The appreciation of the central role of HH signaling in cancer was followed by a high interest in developing safe and specific HH inhibitors of clinical use [49]. Most HH inhibitors target the GPCR SMO and one of them, GDC-0449 or vismodegib, was already given FDA approval for treatment of recurrent, locally advanced or metastatic BCC [50]. However, a report of emergence of resistant disease by SMO mutations in a medulloblastoma patient treated with GDC-0449 suggests that SMO inhibitors efficacy might be enhanced with inhibitors of other targets in the HH pathway or by combination chemotherapy [51]. Inhibitors of the GLI transcription factors and of HH ligands have been described and are in different phases of clinical trials [49].

Vitamin D efficacy for treatment of HH dependent cancer is also being investigated. Vitamin D or its bioactive form calcitriol significantly decreased proliferation and expression of GLI-target genes in HH-dependent pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, cholangiocarcinoma and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) cells in vitro [52–55]. Calcitriol also reduced tumorigenesis of Ptc1−/− BCC cell lines in animal models by both activating a VDR-dependent differentiation pathway and by inhibiting SMO in a VDR-independent manner [53].

The use of statins as cholesterol-lowering drugs for cardiovascular disease was followed by anecdotic evidence, confirmed by some controlled studies, that statins appear to reduce the risk of developing colorectal and prostate cancers [56, 57]. Meta-analysis of large-scale randomized trials for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with statins did not show the same effect, but the validity of those results was controversial [58]. Statins target 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of cholesterol, oxysterols, and 7-hydroxycholesterol (precursor of vitamin D). As it was described before, some mevalonate pathway metabolites are positive regulators of the HH pathway, while vitamin D3 is inhibitory. Thus the overall effect of statins on HH signaling will depend on the nutritional status of individual and will have a maximal inhibitory effect with vitamin D supplementation and low cholesterol intake. It is then plausible that statins can aid in treatment of HH-dependent cancers together with pathway-specific inhibitors if the conditions are maximized to tilt the balance of cholesterol metabolites toward those that negatively regulate the HH pathway.

In summary, the current view of the role of cholesterol derivatives on HH signaling and the promising findings that statins and vitamin D3 may reduce tumor formation and growth of HH-dependent cancers provides a rationale for combining specific HH pathway inhibitors with sterol modulating drugs for the treatment of cancer.

Highlights.

Cholesterol-modified Hedgehogs act on distant target cells as multimers or bound to lipoproteins

Activation of HH signaling is involved in development and maintenance of several cancer types.

Intracellular cholesterol is required in the receiving cell for HH signal transduction

Two sterol types, oxysterols and vitamin D3 are agonists and inhibitors of SMO, respectively

Modulation of sterol synthesis could aid specific HH pathway inhibitors in the treatment of cancer

Acknowledgements

NAR is supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 GM088256.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1. Riobo NA, Manning DR. Pathways of signal transduction employed by vertebrate Hedgehogs. Biochem J. 2007;403:369–379. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061723. * This thorough review explains the basic mechanisms of Hh signal transduction.

- 2.Lee Y, Miller HL, Russell HR, Boyd K, Curran T, McKinnon PJ. Patched2 modulates tumorigenesis in patched1 heterozygous mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6964–6971. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riobo NA, Saucy B, Dilizio C, Manning DR. Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by Smoothened. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12607–12612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600880103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden SK, Fei DL, Schilling NS, Ahmed YF, Hwa J, Robbins DJ. G protein Galphai functions immediately downstream of Smoothened in Hedgehog signaling. Nature. 2008;456:967–970. doi: 10.1038/nature07459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zao Y, Tong C, Jiang J. Hedgehog regulates smoothened activity by inducing a conformational switch. Nature. 2007;450:252–258. doi: 10.1038/nature06225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Sasai N, Ma G, Yue T, Jia J, Briscoe J, Jiang J. Sonic Hedgehog dependent phosphorylation by CK1a and GRK2 is required for ciliary accumulation and activation of smoothened. PLoS Biol. 2011;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001083. e1001083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Chen Y, Shi Q, Yue T, Wnag B, Jiang J. Hedgehog-regulated ubiquitination controls smoothened trafficking and cell surface expression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2012;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001239. e1001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brennan D, Chen X, Cheng K, Mahoney M, Riobo NA. Non-canonical Hedgehog signaling. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:55–72. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00003-1. * This article reviews the domain of non-canonical HH signaling

- 9.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by Sonic Hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou JX, Jia LW, Liu WM, Miao CL, Liu S, Cao YJ, Duan EK. Role of sonic hedgehog in maintaining a pool of proliferating stem cells in the human fetal epidermis. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1698–1704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd N, Grabel L. Hedgehog signaling in murine vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinchilla P, Xiao L, Kazanietz MG, Riobo NA. Hedgehog proteins activate pro-angiogenic responses in endothelial cells through non-canonical signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2001;9:570–579. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.3.10591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, Goodrich LV, Bare JW, Bonifas JM, Quinn AG, Myers RM, Cox DR, Epstein EH, Jr, Scott MP. Human homolog of patched, a candidate for basal cell nevus syndrome. Science. 1996;272:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1668. ** Groundbreaking article describing the first link of the HH pathway in cancer.

- 14. Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, Chidambaram A, Vorechovsky I, Holmberg E, Unden AB, Gillies S, Negus K, et al. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevus basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. ** An independent study also showing that loss of function of PTC results in cancer.

- 15.Raffel C, Jenkins RB, Frederick L, Hebrink D, Alderete B, Fults DW, James CD. Sporadic medulloblastomas contain PTCH mutations. Cancer Res. 1997;57:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorechovský I, Tingby O, Hartman M, Strömberg B, Nister M, Collins VP, Toftgård R. Somatic mutations in the human homologue of Drosophila patched in primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Oncogene. 1997;15:361–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unden AB, Holmberg E, Lundh-Rozell B, Stähle-Bäckdahl M, Zaphiropoulos PG, Toftgård R, Vorechovsky I. Mutations in the human homologue of Drosophila patched (PTCH) in basal cell carcinomas and the Gorlin syndrome: different in vivo mechanisms of PTCH inactivation. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4562–4565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor MD, Liu L, Raffel C, Hui CC, Mainprize TG, Zhang X, Agatep R, Chiappa S, Gao L, Lowrance A, Hao A, et al. Mutations in SUFU predispose to medulloblastoma. Nat Genet. 2002;31:306–310. doi: 10.1038/ng916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brugières L, Remenieras A, Pierron G, Varlet P, Forget S, Byrde V, Bombled J, Puget S, Caron O, Dufour C, Delattre O, et al. High frequency of germline mutations in children with desmoplastic/nodular medulloblastoma younger than 3 years of age. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Apr 16; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.7258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lam CW, Xie J, To KF, Ng HK, Lee KC, Yuen NW, Lim PL, Chan LY, Tong SF, McCormick F. A frequent activated smoothened mutation in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:833–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202360. * The first report of SMO gain-of-function mutations in cancer.

- 21.Mao J, Ligon KL, Rakhlin EY, Thayer SP, Bronson RT, Rowitch D, McMahon AP. A novel somatic mouse model to survey tumorigenic potential applied to the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10171–10178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman DM, Karhadkar SS, Maitra A, Montes De Oca R, Gerstenblith MR, Briggs K, Parker AR, Shimada Y, Eshleman JR, Watkins DN, Beachy PA. Widespread requirement for Hedgehog ligand stimulation in growth of digestive tract tumours. Nature. 2003;425:846–851. doi: 10.1038/nature01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watkins DN, Berman DM, Burkholder SG, Wang B, Beachy PA, Baylin SB. Hedgehog signaling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2003;422:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA. Hedgehog signaling in prostate regeneration, neoplasias and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marini KD, Payne BJ, Watkins DN, Martelotto LG. Mechanisms of Hedgehog signaling in cancer. Growth Factors. 2011;29:221–234. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.610756. ** Excellent review comparing the different modes of tumor promotion by defects in different components of the pathway on the cancer cells or the tumor stroma.

- 26.Dierks C, Grbic J, Zirlik K, Beigi R, Englund NP, Guo GR, Veelken H, Engelhardt M, Mertelsmann R, Kelleher JF, Schultz P, et al. Essential role of stromally induced hedgehog signaling in B-cell malignancies. Nat Med. 2007;13:944–951. doi: 10.1038/nm1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K, Sasajima J, Mizukami Y, Sugiyama Y, Yamazaki M, Fujii R, Kawamoto T, Koizumi K, Sato K, Fujiya M, Sasaki K, et al. Hedgehog promotes neovascularization in pancreatic cancers by regulating Ang-1 and IGF-1 expression in bone-marrow derived pro-angiogenic cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog signaling proteins in animal development. Science. 1996;274:255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.255. ** Biochemical characterization of cholesterol-modified HH.

- 29.Pepinsky RB, Zeng C, Wen D, Rayhorn P, Baker DP, Williams KP, Bixler SA, Ambrose CM, Garber EA, Miatkowski K, Taylor FR, et al. Identification of a palmitic acid-modified form of human Sonic Hedgehog. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14037–14045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Erkner A, Gong R, Yao S, Taipale J, Basler K, Beachy PA. Hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian embryo requires transporter-like function of dispatched. Cell. 2002;111:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00977-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caspary T, García-García MJ, Huangfu D, Eggenschwiler JT, Wyler MR, Rakeman AS, Alcorn HL, Anderson KV. Mouse Dispatched homolog1 is required for long-range, but not juxtacrine, Hh signaling. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1628–1632. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng X, Goetz JA, Suber LM, Scott WJ, Jr, Schreiner CM, Robbins DJ. A freely diffusible form of Sonic hedgehog mediates long-range signaling. Nature. 2001;411:716–720. doi: 10.1038/35079648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panáková D, Sprong H, Marois E, Thiele C, Eaton S. Lipoprotein particles are required for Hedgehog and Wingless signaling. Nature. 2005;435:58–65. doi: 10.1038/nature03504. ** This paper reports for the first time the association between HH and lipoproteins.

- 34.Queiroz KC, Tio RA, Zeebregts CJ, Bijlsma MF, Zijlstra F, Badlou B, de Vries M, Ferreira CV, Spek CA, Peppelenbosch MP, Rezaee F. Human plasma very low density lipoprotein carries Indian hedgehog. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:6052–6059. doi: 10.1021/pr100403q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soleti R, Martinez MC. Sonic hedgehog on microparticles and neovascularization. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:395–428. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokhunts R, Singh S, Chu T, D'Angelo G, Baubet V, Goetz JA, Huang Z, Yuan Z, Ascano M, Zavros Y, Thérond PP, et al. The full-length unprocessed hedgehog protein is an active signaling molecule. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2562–2568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callejo A, Culi J, Guerrero I. Patched, the receptor of Hedgehog, is a lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:912–917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705603105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christ A, Christa A, Kur E, Lioubinski O, Bachmann S, Willnow TE, Hammes A. LRP2 is an auxiliary SHH receptor required to condition the forebrain ventral midline for inductive signals. Dev Cell. 2012;22:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willnow TE, Hilpert J, Armstrong SA, Rohlmann A, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Herz J. Defective forebrain development in mice lacking gp330/megalin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8460–8464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:468–477. doi: 10.1038/nrm2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bidet M, Joubert O, Lacombe B, Ciantar M, Nehmé R, Mollat P, Brétillon L, Faure H, Bittman R, Ruat M, Mus-Veteau I. The hedgehog receptor patched is involved in cholesterol transport. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porter JA, Ekker SC, Park WJ, von Kessler DP, Young KE, Chen CH, Ma Y, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Koonin EV, Beachy PA. Hedgehog patterning activity: Role of a lipophilic modification mediated by the carboxy-terminal autoprocessing domain. Cell. 1996;86:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taipale J, Cooper MK, Maiti T, Beachy PA. Patched acts catalytically to suppress the activity of Smoothened. Nature. 2002;418:892–897. doi: 10.1038/nature00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eaton S. Multiple role for lipids in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:437–445. doi: 10.1038/nrm2414. * Extensive review explaining the role of lipids in the HH pathway, with focus on the transport of lipid-modified HH ligands.

- 45.Nachtergaele S, Mydock LK, Krishnan K, Rammohan J, Schlesinger PH, Covey DF, Rohatgi R. Oxysterols are allosteric activators of the oncoprotein Smoothened. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:211–220. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Corcoran RB, Scott MP. Oxysterols stimulate Sonic hedgehog signal transduction and proliferation of medulloblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8408–8413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602852103. ** Outstanding study that characterizes the role of oxysterols as SMO agonists and shows its biological implications.

- 47.Dwyer JR, Sever N, Carlson M, Nelson SF, Beachy PA, Parhami F. Oxysterols are novel activators of the hedgehog signaling pathway in pluripotent mesenchymal cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8959–8968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bijlsma MF, Spek CA, Zivkovic D, van de Water S, Rezaee F, Peppelenbosch MP. Repression of smoothened by patched-dependent (pro-) vitamin D3 secretion. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040232. * This study proposed that PTC can act in non-cell autonomous fashion to repress SMO by secretion of pro vitamin D3.

- 49. Mas C, Ruiz i Altaba A. Small molecule modulation of HH-GLI signaling: current leads, trials and tribulations. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.016. ** Comprehensive review on the development and clinical trials of HH pathway inhibitors.

- 50.Oncology. Vol. 26. Williston Park: 2012. Vismodegib granted FDA approval for treatment of basal cell carcinoma; pp. 174–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yauch RL, Dijkgraaf GJ, Alicke B, Januario T, Ahn CP, Holcomb T, Pujara K, Stinson J, Callahan CA, Tang T, Bazan JF, Kan Z, et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 2009;326:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baek S, Lee YS, Shim HE, Yoon S, Baek SY, Kim BS, Oh SO. Vitamin D3 regulates cell viability in gastric cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. Anat Cell Biol. 2011;44:204–209. doi: 10.5115/acb.2011.44.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uhmann A, Niemann H, Lammering B, Henkel C, Hess I, Nitzki F, Fritsch A, Prüfer N, Rosenberger A, Dullin C, Schraepler A, et al. Antitumoral effects of calcitriol in basal cell carcinomas involve inhibition of hedgehog signaling and induction of vitamin D receptor signaling and differentiation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2179–2188. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang JY, Xiao TZ, Oda Y, Chang KS, Shpall E, Wu A, So PL, Hebert J, Bikle D, Epstein EH., Jr Vitamin D3 inhibits hedgehog signaling and proliferation in murine Basal cell carcinomas. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:744–751. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruggemann LW, Queiroz KC, Zamani K, van Straaten A, Spek CA, Bijlsma MF. Assessing the efficacy of the hedgehog pathway inhibitor vitamin D3 in a murine xenografts model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:79–88. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.1.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poynter JN, Gruber SB, Higgins PD, Almog R, Bonner JD, Rennert HS, Low M, Greenson JK, Rennert G. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2184–2192. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon J, Tewoderos S, Garzotto M, Beer TM, Derenick R, Palma A, Farris PE. Statins and prostate cancer risk: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:318–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM. Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]