TEXT

Early microbiologists argued over whether the different forms they saw through their rudimentary microscopes—the rods, the cocci, the commas, and the spirals—were different species or merely different developmental stages of a small number of organisms (1). Pure culture techniques developed in the second half of the 19th century laid that debate to rest. By now, it is well established that most bacteria get their characteristic size and shape from the peptidoglycan (PG) wall in which they live. But this conclusion begs the question: how does the cell wall get its shape? Our understanding of this topic has been the subject of several excellent reviews (2–4). But it is important to note that previous efforts to address this question have involved screening for mutants or conditions that result in loss of normal morphology. An elegant paper by Ranjit and Young published in this issue of the Journal of Bacteriology (5) describes a completely different approach to the question. The authors used lysozyme to convert Escherichia coli cells to spheroplasts and then watched as these cells recovered normal morphology during outgrowth. Mutants defective in a number of cell envelope-associated genes proved to be incapable of regenerating rod morphology. Remarkably, the genes in question are not critical for maintaining normal rod morphology under standard growth conditions. This means the morphogenetic systems required for maintaining cell shape are not sufficient for generating cell shape de novo.

Sculpting the PG sacculus.

The PG sacculus is an enormous bag-like macromolecule composed of glycan strands joined by short peptide cross-links (6, 7). The sacculus surrounds the inner (cytoplasmic) membrane in a tough but somewhat elastic exoskeleton. We know this exoskeleton is the proximal determinant of cell shape because removing it by digestion with lysozyme rapidly converts bacteria of essentially any starting morphology to round spheroplasts. Conversely, purified sacculi retain the contours of the cells from which they were derived.

The geometry of the sacculus is determined by the combined action of multiple PG synthases and hydrolases that remodel the PG during growth and division. The activity of the hydrolases must be carefully controlled and coordinated with that of the synthases to avoid lysis and preserve cell shape. This coordination is exerted in part by colocalizing the synthases and hydrolases to multiprotein complexes (7). The assembly and activity of these complexes are guided by two major cytoskeletal elements containing either the tubulin-like protein FtsZ or the actin-like protein MreB. FtsZ is the master regulator of the bacterial division apparatus, often referred to as the divisome, which in E. coli assembles at the midcell and contains at least 30 different types of proteins (8). Among the components of the divisome are multiple PG synthases, hydrolases, and accessory proteins that link these enzymes to FtsZ and regulate their activities (e.g., see references 9 to 12). The MreB protein (or its homologs) is a critical component of an analogous protein assembly sometimes called the “elongasome” that localizes to the lateral wall of rod-shaped bacteria and orchestrates elongation.

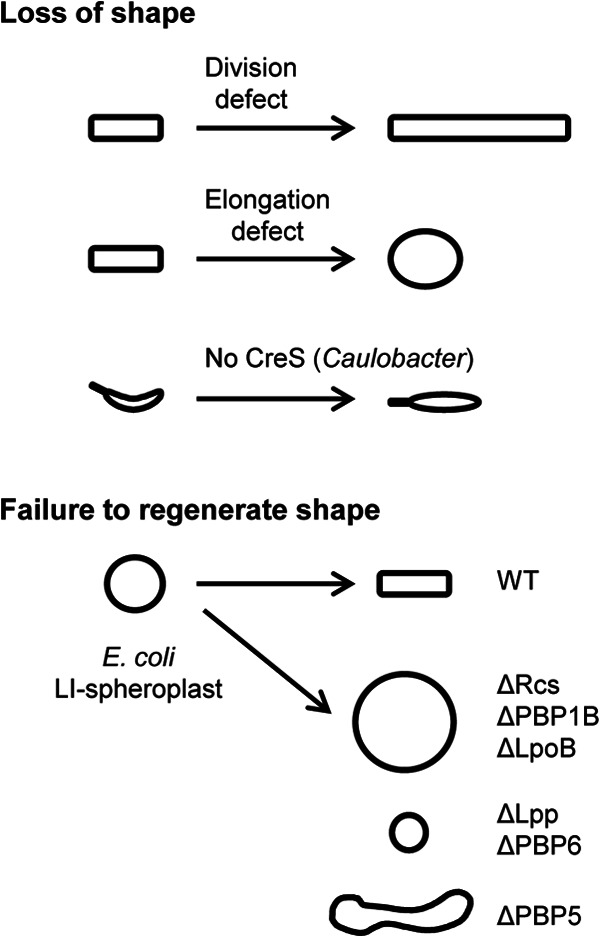

We know these assemblies are important for cell shape because mutations or drugs that inactivate them have telltale morphological effects. Thus, inactivation of the divisome results in growth as a long filament, while inactivation of the elongasome causes cells to become large and round (Fig. 1). Moreover, bacteria that acquire more complex shapes, like crescents and spirals, or execute dramatic changes, like spore formation, do so by modifying the cell wall either directly or by manipulating the FtsZ/MreB morphogenetic systems (13–15).

Fig 1.

Approaches for identifying genes that govern cell shape. The upper set of cartoons depicts representative findings from screenings for mutants that fail to maintain their characteristic morphology. The lower set summarizes phenotypes uncovered by Ranjit and Young in their screening for E. coli genes needed to generate rod morphology de novo. WT, wild type.

An assay to study generation of cell shape de novo.

This brings up a chicken-and-egg question: if cell shape is determined by replicating or modifying an existing PG sacculus, how does that sacculus get its shape in the first place? Enter Ranjit and Young, who resurrected a decades-old observation that bacteria that have lost their cell wall by digestion with lysozyme can often recover their original morphology under suitable conditions (16–18). Ranjit and Young subjected E. coli to mild osmotic shock in the presence of lysozyme. The resulting lysozyme-induced (LI) spheroplasts were plated on soft agar containing nutrients and sucrose for osmotic protection, and time-lapse microscopy was used to observe their fate. As anticipated from the older studies, growth and division were irregular in the absence of a cell wall but the original rod morphology was restored in about five generations. Many of the intermediate forms exhibited branches. Previous work has shown that branches in E. coli result from abortive attempts at septation (19). Ranjit and Young obtained evidence that this is also the case in recovering spheroplasts by showing that branches emanate from sites where FtsZ-green fluorescent protein had localized transiently.

Unexpected proteins needed to generate rod shape de novo.

The authors then challenged a collection of about 25 E. coli mutants to recover from the LI spheroplast state. This effort led to the identification of eight proteins that are important for regenerating a rod shape: RcsBCF, PBP1B, LpoB, Lpp, PBP5, and PBP6. Remarkably, none of these proteins is needed for maintaining a rod shape under normal growth conditions. Several of these proteins (RcsBCF, PBP1B, and LpoB) have also been reported to be important for survival or E. coli L forms, spheroplasts generated by growth in the presence of β-lactams (20, 21). The convergence of these approaches is both reassuring and intriguing. An important challenge for the future is to establish what role these proteins play in regeneration of rod morphology. At present, we can only speculate.

The Rcs phosphorelay system responds to a variety of cell envelope stresses, including PG damage induced by β-lactams (22). Presumably, one or more of the 150+ genes under Rcs control (22, 23) has a novel role in cell shape determination that awaits discovery. PBP1B and LpoB form a complex that is one of two major PG synthesis enzymes in E. coli (23, 24). The other major synthase is the PBP1A/LpoA complex, which was found not to be necessary for regenerating rod morphology. A noteworthy difference is that PBP1B/LpoB but not PBP1A/LpoA can tether the outer membrane to the inner membrane (25). Ranjit and Young noted morphological defects that led them to suspect the tethering function of PBP1B/LpoB is critical for the recovery of LI spheroplasts. But there are other possibilities: PBP1A/LpoA might not be active enough to generate sufficient PG, or PBP1B/LpoB might be better able to shuttle between elongation and division roles.

Lpp (also known as Braun's lipoprotein) is an abundant outer membrane lipoprotein that contributes to outer membrane stability and tethering of the outer membrane to the PG (26, 27). These functions are of obvious potential utility to a recovering spheroplast, especially considering the large number of outer membrane proteins that contribute to the biogenesis of the sacculus (3). But this hand waving begs the question of why Lpp is not required for maintaining rod morphology during normal growth.

PBP5 and PBP6 are carboxypeptidases that remove terminal d-alanine residues from pentapeptide side chains of PG (28). This prevents those side chains from serving as donors for transpeptidation. Despite the fact that PBP5 and PBP6 have identical enzymatic specificities, loss of PBP5 pushed the development of LI spheroplasts toward filamentation, while loss of PBP6 pushed their development toward coccus formation. PBP5 is the more active of these two enzymes and localizes to sites of active PG synthesis (29, 30). Does a reduced availability of transpeptidation donors favor elongation over division in recovering LI spheroplasts?

Questions.

The experimental system developed by Ranjit and Young is ripe for further exploration. These are early days, so the possibilities seem endless, but some of the questions that come to mind include the following. What genes under Rcs control are important for regenerating shape? Can an artificial protein designed to tether the inner and outer membranes rescue loss of PBP1B or LpoB? Does Lpp have to attach to the PG to facilitate recovery? Does the PG made by spheroplasts lacking PBP5 or PBP6 exhibit structural abnormalities? How many more genes for de novo shape generation await discovery? Is this assay just an exciting new way to explore the control of cell shape, or do bacteria have to recover from the spheroplast state in a host environment?

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Work on cell division and morphology in my lab is supported by NIH grant GM083975.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 March 2013

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cohen F. 1960. Studies on the biology of the bacilli, p 49–56 In Brock TD. (ed), Milestones in microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2. Margolin W. 2009. Sculpting the bacterial cell. Curr. Biol. 19:R812–R822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2012. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Young KD. 2010. Bacterial shape: two-dimensional questions and possibilities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:223–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ranjit DK, Young KD. 2013. The Rcs stress response and accessory envelope proteins are required for de novo generation of cell shape in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 195:2452–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vollmer W, Blanot D, de Pedro MA. 2008. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:149–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Höltje JV. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:181–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Boer PA. 2010. Advances in understanding E. coli cell fission. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13:730–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiss DS, Chen JC, Ghigo JM, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 1999. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J. Bacteriol. 181:508–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertsche U, Kast T, Wolf B, Fraipont C, Aarsman ME, Kannenberg K, von Rechenberg M, Nguyen-Distèche M, den Blaauwen T, Höltje JV, Vollmer W. 2006. Interaction between two murein (peptidoglycan) synthases, PBP3 and PBP1B, in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 61:675–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang DC, Peters NT, Parzych KR, Uehara T, Markovski M, Bernhardt TG. 2011. An ATP-binding cassette transporter-like complex governs cell-wall hydrolysis at the bacterial cytokinetic ring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:E1052–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sham LT, Barendt SM, Kopecky KE, Winkler ME. 2011. Essential PcsB putative peptidoglycan hydrolase interacts with the essential FtsXSpn cell division protein in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:E1061–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ausmees N, Kuhn JR, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2003. The bacterial cytoskeleton: an intermediate filament-like function in cell shape. Cell 115:705–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sycuro LK, Wyckoff TJ, Biboy J, Born P, Pincus Z, Vollmer W, Salama NR. 2012. Multiple peptidoglycan modification networks modulate Helicobacter pylori's cell shape, motility, and colonization potential. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002603 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levin PA, Losick R. 1996. Transcription factor Spo0A switches the localization of the cell division protein FtsZ from a medial to a bipolar pattern in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 10:478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zinder ND, Arndt WF. 1956. Production of protoplasts of Escherichia coli by lysozyme treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 42:586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elliott TS, Ward JB, Wyrick PB, Rogers HJ. 1975. Ultrastructural study of the reversion of protoplasts of Bacillus licheniformis to bacilli. J. Bacteriol. 124:905–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller IL, Wiebe W, Landman OE. 1968. Gelatin-induced reversion of protoplasts of Bacillus subtilis to the bacillary form: photomicrographic study. J. Bacteriol. 96:2171–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Pedro MA, Young KD, Höltje JV, Schwarz H. 2003. Branching of Escherichia coli cells arises from multiple sites of inert peptidoglycan. J. Bacteriol. 185:1147–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glover WA, Yang Y, Zhang Y. 2009. Insights into the molecular basis of L-form formation and survival in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4:e7316 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joseleau-Petit D, Liebart JC, Ayala JA, D'Ari R. 2007. Unstable Escherichia coli L forms revisited: growth requires peptidoglycan synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 189:6512–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laubacher ME, Ades SE. 2008. The Rcs phosphorelay is a cell envelope stress response activated by peptidoglycan stress and contributes to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 190:2065–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferrières L, Clarke DJ. 2003. The RcsC sensor kinase is required for normal biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K-12 and controls the expression of a regulon in response to growth on a solid surface. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1665–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paradis-Bleau C, Markovski M, Uehara T, Lupoli TJ, Walker S, Kahne DE, Bernhardt TG. 2010. Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 143:1110–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Typas A, Banzhaf M, van den Berg van Saparoea B, Verheul J, Biboy J, Nichols RJ, Zietek M, Beilharz K, Kannenberg K, von Rechenberg M, Breukink E, den Blaauwen T, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2010. Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis by outer-membrane proteins. Cell 143:1097–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braun V, Rehn K. 1969. Chemical characterization, spatial distribution and function of a lipoprotein (murein-lipoprotein) of the E. coli cell wall. The specific effect of trypsin on the membrane structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 10:426–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fung J, MacAlister TJ, Rothfield LI. 1978. Role of murein lipoprotein in morphogenesis of the bacterial division septum: phenotypic similarity of lkyD and lpo mutants. J. Bacteriol. 133:1467–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghuysen JM. 1991. Serine beta-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:37–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chowdhury C, Nayak TR, Young KD, Ghosh AS. 2010. A weak dd-carboxypeptidase activity explains the inability of PBP 6 to substitute for PBP 5 in maintaining normal cell shape in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 303:76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potluri L, Karczmarek A, Verheul J, Piette A, Wilkin JM, Werth N, Banzhaf M, Vollmer W, Young KD, Nguyen-Distèche M, den Blaauwen T. 2010. Septal and lateral wall localization of PBP5, the major d,d-carboxypeptidase of Escherichia coli, requires substrate recognition and membrane attachment. Mol. Microbiol. 77:300–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]