Abstract

Bacterial type II toxin-antitoxin systems are widespread in bacteria. Among them, the RelE toxin family is one of the most abundant. The RelEK-12 toxin of Escherichia coli K-12 represents the paradigm for this family and has been extensively studied, both in vivo and in vitro. RelEK-12 is an endoribonuclease that cleaves mRNAs that are translated by the ribosome machinery as these transcripts enter the A site. Earlier in vivo reports showed that RelEK-12 cleaves preferentially in the 5′-end coding region of the transcripts in a codon-independent manner. To investigate whether the molecular activity as well as the cleavage pattern are conserved within the members of this toxin family, RelE-like sequences were selected in Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Spirochaetes and tested in E. coli. Our results show that these RelE-like sequences are part of toxin-antitoxin gene pairs, and that they inhibit translation in E. coli by cleaving transcripts that are being translated. Primer extension analyses show that these toxins exhibit specific cleavage patterns in vivo, both in terms of frequency and location of cleavage sites. We did not observe codon-dependent cleavage but rather a trend to cleave upstream purines and between the second and third positions of codons, except for the actinobacterial toxin. Our results suggest that RelE-like toxins have evolved to rapidly and efficiently shut down translation in a large spectrum of bacterial species, which correlates with the observation that toxin-antitoxin systems are spreading by horizontal gene transfer.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria thrive in ever-changing environments; therefore, they have evolved regulatory mechanisms allowing rapid modulation of gene expression and adaptation. Among these mechanisms, ribonucleases (RNAses) play an important regulatory role by adjusting RNA levels (for a review, see reference 1). Escherichia coli has more than 20 RNases involved in different processes, such as RNA quality control, RNA maturation, and stress response modulation. In addition, E. coli carries numerous RNases that act as bacteriocins (for a review, see reference 2) or belong to CRISPR systems (for a review, see reference 3) and toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems (for a review, see reference 4).

TA systems are classified into different types depending on the nature and mode of action of the antitoxin, with the toxin always being a protein. Type II systems are generally composed of two genes organized in an operon, the first gene encoding an antitoxin protein and the second a toxin. These systems are abundant in bacterial genomes. In some bacterial species, such as Nitrosomonas europaea (Proteobacteria) and Chlorobium chlorochromatii (Chlorobi), predicted type II TA systems represent around 2.5% of the total predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of these genomes (5). Type II systems are associated with mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids and phages, as well as with chromosomes, in which they may be part of or constitute by themselves genomic islands/islets (for a review, see reference 4). It has been proposed that they move between genomes through horizontal gene transfer. The question of their biological roles remains debated, although several interesting hypotheses have emerged, notably their implications in programmed cell death, stress response, persistence, stabilization of large genomic regions, or mobile genetic elements (for a review, see reference 4).

Interestingly, the vast majority of type II toxins that have been identified and characterized so far are endoribonucleases (also denoted as mRNA interferases) (7–14). One of the best characterized is the RelEK-12 toxin of the relBEK-12 system of E. coli K-12 (7). RelEK-12 is an endoribonuclease that cleaves mRNAs in a translation-dependent manner. Free RelEK-12 enters the ribosomal A site and binds to the ribosome 30S subunit (15, 16). Resolution of the three-dimensional structure of the RelEK-12-ribosome complex showed that subsequent to complex formation, the target mRNA in the A site is reoriented so that RelEK-12 catalyzes cleavage of the transcript (16). Three RelEK-12 residues are essential for this activity: Y87, which reorients and stabilizes the mRNA to allow the nucleophilic attack; R61, which stabilizes the cleavage transition state; and R81, which acts as a general acid (16). RelEK-12 cleaves preferentially in the 5′ region of the target mRNA, usually between the second and third nucleotide of codons or between two codons (17). The RelBK-12 antitoxin wraps around the toxin, thereby inhibiting its entry in the A site and leading to structural rearrangements that disrupt the RelEK-12 catalytic site (18, 19).

RelE-like toxins belong to the widespread type II ParE/RelE superfamily (5, 20). Type II toxin superfamilies are based on similarities at the level of amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structure prediction/determination (5, 21). Interestingly, this superfamily is composed of two functionally (although not structurally) distinct families that are either endoribonucleases, as mentioned above (RelE family), or proteins inhibiting DNA-gyrase and DNA replication (ParE family) (6, 22). This suggests that these two families share a common ancestor and have functionally diverged during evolution. Several RelE-like proteins, such as YoeB (14, 23), MqsR (24), YafQ (25), and YgjN (10), of Escherichia coli K-12 have been characterized both at the activity and structural levels. While they all share a fold with RelEK-12 and most of them cleave mRNAs in a translation-dependent manner, differences are observed at the cleavage specificity level. The YoeB toxin cleaves predominantly between the start and the second codon (23), and minor cleavage sites are observed downstream in the target mRNA, preferentially upstream of purines (26). YafQ preferentially cleaves AAA codons (25), while YgjN does not show any specificity (10). MqsR has been shown to act in a translation-independent manner both in vivo and in vitro with a preference for GC(U/A) codons (10, 24). Three RelE-like toxins from different proteobacteria (Brucella abortus, Helicobacter pylori, and Proteus vulgaris) were characterized. Toxins from B. abortus and H. pylori were shown to cleave RNAs in a translation-independent manner in vitro (27, 28). For H. pylori RelE-like toxin, cleavage occurs preferentially upstream of purines. Finally, a RelE-like toxin from Proteus vulgaris was shown to cleave preferentially at AAA sequences in a translation-dependent manner (29).

To gain further insights into cleavage specificity within the RelE family, we investigated the mechanism of action of RelE homologues found in distantly related bacterial species. The activity of 6 RelE-like sequences from different phyla was tested in E. coli. These RelE-like sequences are part of type II TA systems. They cleave the E. coli lpp and ompA transcripts in a translation-dependent manner without showing strong codon specificity, although these toxins tend to cleave upstream of purines and between the second and third positions of codons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and media.

For additional details on strains and plasmids used in this study, see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Strains.

An E. coli strain, deleted for the 10 type II TA systems identified at the time we started this work, was constructed to avoid any interference with the activity of the RelE-like toxins tested (30, 31). Note that the toxins of these 10 systems are all mRNA interferases. The MG1655Δ10 strain was constructed starting from MG1655Δ5 (ΔmazEF ΔrelBE ΔchpB ΔdinJ-yafQ ΔyefM-yoeB) (32) by successive deletions of the yafNO, prlF-yhaV, hicAB, ygjMN, and mqsRA loci. Deletions were constructed using the mini-lambda RED system as described in reference 33. Locus replacement by antibiotic resistance genes was checked by PCR amplification, and antibiotic resistance genes were subsequently removed using the pCP20 thermosensitive plasmid as described in reference 34. The ygjMN and mqsRA deletions were P1 transduced into MG1655Δ8 and MG1655Δ9, respectively, because in MG1655Δ7, recombination occurred preferentially at the FLP recombination target (FRT) sites rather than at the loci of interest.

The MG1655Δ10 strain was used for all of the experiments described in this work, except for the lpp mRNA Northern blotting. Those experiments were performed with an MG1655Δ10 Δlpp::kan strain (constructed by P1 transduction of lpp::kan in MG1655Δ10) transformed with the pSC710 or pSC711 plasmid (35).

Toxin- and antitoxin-expressing plasmids.

Toxin and antitoxin genes were amplified by PCR on genomic DNA using the appropriate primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Toxin PCR fragments, digested by the XbaI and PstI restriction enzymes, were cloned in the pBAD33 vector digested by the same enzymes. Antitoxin PCR fragments, digested by the EcoRI and PstI restriction enzymes, were cloned into the pKK223-3 vector digested by the same enzymes.

Media.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and M9 minimal medium (KH2PO4 [22 mM], Na2HPO4 [42 mM], NH4Cl [19 mM], MgSO4 [1 mM], CaCl2 [0.1 mM], NaCl [9 mM], vitamin B1 [1 mg ml−1]) supplemented with Casamino Acids (0.2%) and carbon sources (1% glucose, 1% glycerol, 1% arabinose) were used to grow bacteria. Ampicillin and chloramphenicol were added at respective final concentrations of 100 and 20 mg ml−1. Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was used at final concentrations of 0.01 or 1 mM.

Toxicity and antitoxicity assays.

Colonies of MG1655Δ10 containing the pBAD33 vector or its derivatives carrying the toxin genes, as well as the pKK223-3 vector or its derivatives carrying the cognate antitoxin genes, were diluted in 10−2M MgSO4. Ten-μl aliquots of the serial dilutions were plated on M9 minimum solid media containing the appropriate antibiotics and inducers. CFU were observed after overnight incubation of the plates at 37°C.

Northern blotting.

Overnight cultures were diluted and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.6 in LB medium, and expression of the toxins was induced by addition of 1% arabinose. Total RNAs were extracted at the times indicated in the figures with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Qiagen kit by following the manufacturer's specifications or using the hot phenol method as described in reference 36. Five-μg aliquots of total RNA extracts were separated on 1% agarose gels and transferred to a nylon membrane in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) buffer. The membrane was hybridized overnight with the labeled primers (Ambion NorthernMax kit). Primers were labeled with 3 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity, 3,000 Ci/mmol). The Promega T4 polynucleotide kinase was used for primer phosphorylation. Labeled primers were purified by PAGE (12% acrylamide). The experiments were performed at least twice.

Primer extensions.

Ten μg of total RNA was hybridized with 0.2 pmol of labeled primers for 10 min. Primer sequences are described in reference 17. The mixture was cooled on ice. Reverse transcription was performed with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Sequencing reactions were performed using the USB Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit. Cleavage patterns of the lpp, ompA, and rpsA mRNAs were tested before induction and 30 min after toxin expression. The lpp transcript (237 bp) was analyzed using one primer covering 195 nucleotides. In order to cover the full-length ompA mRNA (1,041 nucleotides), five primers were used, allowing the reading of a total of 957 nucleotides with 126 nucleotides for ompA1, 180 for ompA2, 213 for ompA3 and ompA4, and 225 for ompA5 (17). The rpsA primer covers the 5′-end 188 nucleotides over the 1,674 nucleotides of the full-length rpsA. The experiments were performed at least twice.

Potential cleavage rate in the original host genomes.

For each toxin, the prevalence of the three codons cleaved most frequently in the lpp and ompA transcripts were estimated in bacterial genomes based on the codon usage in each species (http://exon.gatech.edu/GeneMark/metagenome/CodonUsageDatabase/). Considering that these codons are cleaved with an efficiency of 100%, the inverse of the sum of frequencies estimates the toxin cleavage rate in the different genomes.

RESULTS

Detection of RelE-like toxins in bacterial genomes.

The ParE/RelE superfamily is one of the most abundant type II toxin superfamilies in bacterial genomes (5). Previous studies revealed that these toxins are quite divergent, although they share or are predicted to adopt a common RelE fold (21). To test whether toxins belonging to this superfamily share common molecular mechanisms and cleavage specificity despite protein sequence divergence, six toxins detected on the chromosomes of distantly related bacterial species were selected for further analyses (RelEO157 from Escherichia coli O157:H7 [Gammaproteobacteria], RelERpa from Rhodopseudomonas palustris BisB18 [Alphaproteobacteria], RelESme from Sinorhizobium meliloti [Alphaproteobacteria], RelETde from Treponema denticola [Spirochaetes], RelEMav from Mycobacterium avium [Actinobacteria], and RelENsp from Nostoc sp. [Cyanobacteria]) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). These putative toxins appear to be part of genomic islands, as indicated by their GC content and their different distribution among isolates from the same species (data not shown).

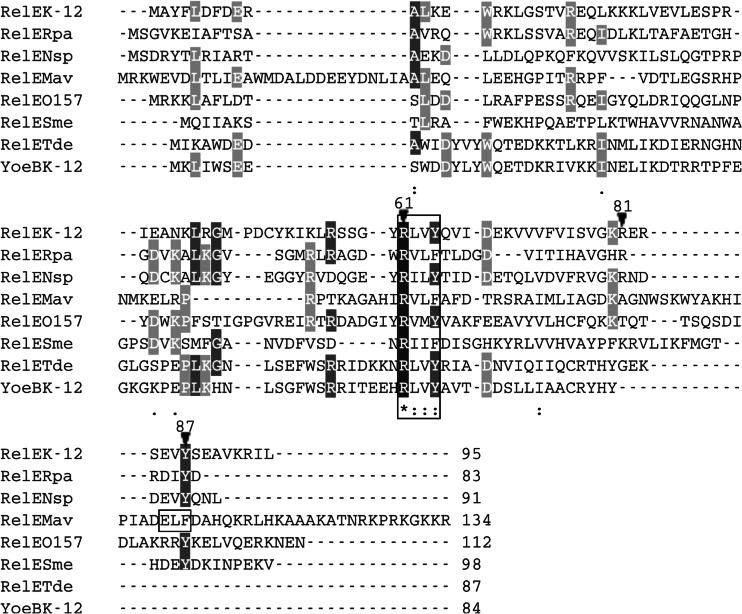

Amino acid sequence comparisons confirmed that RelE-like sequences are quite divergent, even those originating from the same or closely related bacterial species (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows that the RelE-like sequences present 24 to 47% similarity and 15 to 28% identity with the canonical RelEK-12. Note that RelETde presents 52% identity and 66% similarity to the YoeBK-12 toxin. Similarity between the different RelE-like sequences is even lower, with only a few percentage points of similarity between RelESme and RelETde or RelEO157. Despite this very low conservation at the amino acid sequence level, predicted secondary and tertiary structures indicated that these RelE-like sequences share a similar fold with RelEK-12 toxin (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Alignment of the RelE-like sequences with RelEK-12 and YoeBK-12. Amino acid sequences were aligned with MAFFT (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/). Residues highlighted in dark gray are conserved in 80% of the sequences, in medium gray for 70% conservation, and in light gray for 50% conservation. Arrows indicate residues important for the catalytic activity of RelEK-12. An asterisk indicates identical amino acids; colons and dots indicate similar residues. Boxes show conserved motifs. The ELF motif in RelEMav is conserved in HP0894 (28).

Table 1.

Similarity and identity between the RelE-like toxins and the RelEK-12 and YoeBK-12 canonical toxinsa

| Toxin | RelEK-12 | RelERpa | RelENsp | RelEMav | RelEO157 | RelESme | RelETde | YoeBK-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RelEK-12 | 24 | 28 | 15 | 19 | 16 | 17 | 16 | |

| RelERpa | 47 | 28 | 14 | 13 | 20 | 20 | 17 | |

| RelENsp | 43 | 46 | 4 | 18 | 13 | 17 | 21 | |

| RelEMav | 27 | 24 | 7 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 19 | |

| RelEO157 | 35 | 24 | 32 | 30 | 3 | 4 | 14 | |

| RelESme | 24 | 26 | 23 | 24 | 5 | 5 | 9 | |

| RelETde | 25 | 37 | 28 | 27 | 11 | 4 | 52 | |

| YoeBK-12 | 30 | 31 | 36 | 29 | 30 | 23 | 66 |

Amino acid sequence identity (%) and similarity (%) are indicated in gray and white, respectively, as determined using the NEEDLE alignment software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_needle/index.html).

Functional and structural data regarding RelEK-12 indicate that the active-site residues R61, R81, and Y87 are essential for mRNA cleavage, as single mutations lead to decreased activity (16). Amino acid sequence alignments show that these residues are conserved in the eight RelE-like sequences, although to different extents (Fig. 1). While R61 is conserved in the 8 sequences, Y87 and R81 are less conserved (5 and 3, respectively, out of 8). The M. avium RelE, RelEMav, possesses a phenylalanine at the position corresponding to Y87, similar to the H. pylori HP0894 RelE-like toxin (F88) and E. coli YafQ (F91) (28, 37). In addition, RelEMav contains part of an HP0894 motif involved in substrate recognition (E107, L108, and F109) (28).

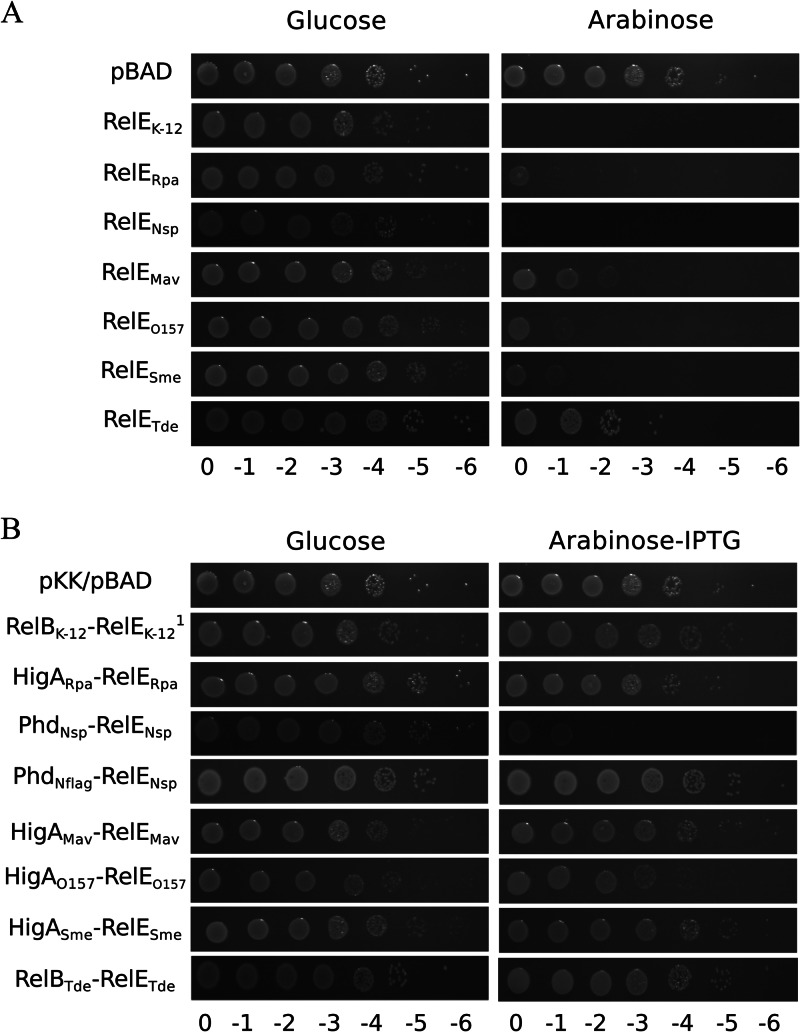

To test the toxic activity of the RelE-like sequences, the corresponding genes were cloned in the pBAD33 vector under the control of the pBAD promoter. These constructs, as well as the pBAD33-relEK-12 plasmid, were transformed in E. coli MG1655 deleted of 10 type II TA systems (MG1655Δ10; see Materials and Methods) to avoid any interference with the 10 endogenous mRNA interferases encoded by these loci (30, 31). Transformation of MG1655Δ10 with the pBAD33-yoeBK-12 plasmid was not successful, even in the presence of glucose to repress expression from the pBAD promoter, most likely due to the absence of the chromosomal copy of the system (38). Figure 2A shows that ectopic overexpression of the 6 relE-like genes inhibits E. coli growth.

Fig 2.

RelE-like toxins inhibit E. coli growth and constitute TA systems. (A) Serial dilutions of the MG1655Δ10 strain, containing the pBAD33 control vector or its derivatives with the relE-like genes, were plated on M9 minimal media containing either glucose (1%) or arabinose (1%) and the appropriate antibiotics. (B) Serial dilutions of the MG1655Δ10 strain, containing the pBAD33 and pKK223-3 control vectors or their derivatives with the relE-like genes and their cognate antitoxin genes, were plated on M9 minimal media containing either glucose (1%) or arabinose (1%), along with IPTG (1 mM) and the appropriate antibiotics. Note that the pSC101-lacIq plasmid was cotransformed with pKK223-3-relBK-12 to repress relBK-12 expression, since it appears to be toxic (data not shown). IPTG was used at a final concentration of 0.01 mM to induce antitoxin expression. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and survival was estimated.

RelE toxins are associated with antitoxins belonging to different superfamilies.

The 6 RelE-like toxins are associated with predicted antitoxins belonging to three different superfamilies, i.e., Phd, HigA, and RelB (see Fig. S1 and Table S3 in the supplemental material). The toxins of T. denticola and Nostoc sp. are associated with predicted relBTde and phdNsp genes, respectively. These loci exhibit a canonical organization in which the antitoxin genes precede those of the toxins. In contrast, the four other systems present a reverse organization in which the toxin gene is located upstream of the predicted antitoxin gene. Toxins from R. palustris, S. meliloti, M. avium, and E. coli O157:H7 are associated with predicted HigA antitoxins (see Fig. S1 and Table S3).

The predicted antitoxin genes were cloned in the pKK223-3 vector under the control of the pTac promoter. These antitoxin-containing plasmids were transformed in the MG1655Δ10 strain containing the toxin-expressing plasmids (Fig. 2A). Except for the relENsp-phdNsp gene pair, coexpression of the predicted antitoxins with their respective toxins restores normal growth, showing that these gene pairs constitute functional TA systems (Fig. 2B). Coexpression of PhdNsp with RelENsp only partially restores E. coli cell growth (Fig. 2B). To visualize the expression of this putative antitoxin by Western blotting, an N-terminal Flag tag was added to PhdNsp (PhdNflag), and surprisingly, this version of the antitoxin completely restored cell growth upon coexpression with relENsp (Fig. 2B), while addition of the Flag tag to the C terminus did not restore cell growth (data not shown). Altogether, these data indicate that PhdNsp is indeed an antitoxin, and that blocking its N terminus might increase either its translation or its stability.

Translation-dependent mRNA cleavage.

It was shown previously that overexpression of RelESme, RelEMav, and RelEO157 leads to a decrease of the global translation rate in E. coli (5). As expected, ectopic overexpression of RelERpa, RelENsp, and RelETde toxins also inhibits translation (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). A series of Northern blot experiments was then carried out to test whether these toxins affect mRNA stability in a translation-dependent manner, as observed for the canonical RelEK-12 toxin. Ectopic overexpression of the 6 RelE-like toxins leads to ompA degradation (Fig. 3). Translation dependence was tested using a well-established mRNA assay consisting of a version of the lpp mRNA that is not translated due to the mutation of the start codon in a lysine AAG codon (35). Degradation of this mRNA was tested in the MG1655Δ10 Δlpp::kan strain. While degradation was observed in the case of wild-type lpp mRNA, the mutant transcript remained stable in all cases, indicating that the RelE homologues cleave mRNAs in a translation-dependent manner (see Fig. S3).

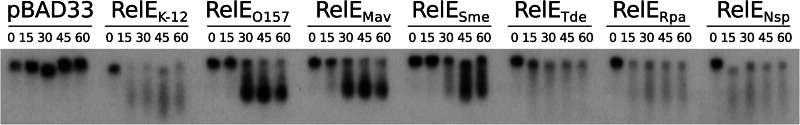

Fig 3.

RelE-like toxins induce mRNA cleavage. The MG1655Δ10 strain, containing the pBAD33 control vector or its derivatives with the relE-like genes, was grown in LB to an OD600 of ∼0.6. Toxin expression was then induced by addition of arabinose (1%). Total RNAs were extracted at 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after toxin induction and were used for Northern blot analysis of the ompA mRNA using specific probes as described in Materials and Methods.

Cleavage pattern specificity.

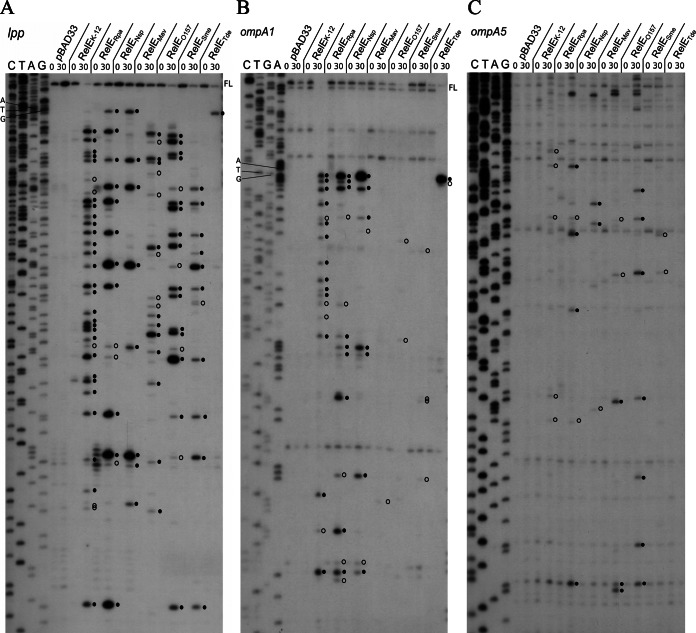

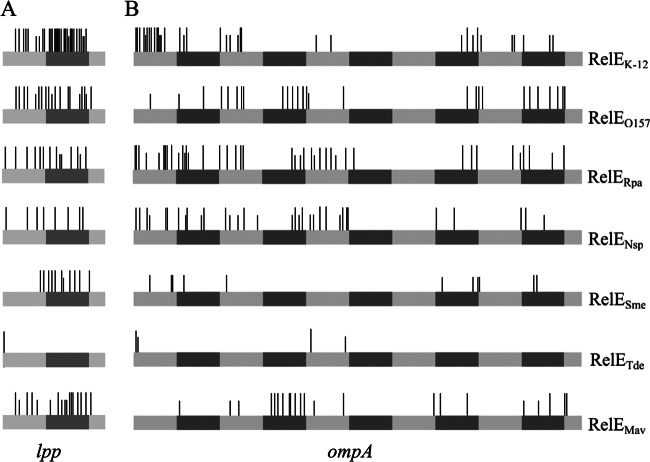

Primer extension experiments on the lpp and ompA mRNAs were performed under overexpression of the different RelE toxins. Interestingly, expression of these toxins leads to different cleavage patterns in terms of cleavage specificity as well as frequency (Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). No cleavage is detected in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of the test mRNAs, confirming that the 6 RelE homologues cleave mRNAs in a translation-dependent manner. The toxins did not show codon specificity, although 5 of them preferentially cut between the second and third position and upstream of a purine.

Fig 4.

RelE-like toxin expression leads to distinct cleavage patterns on the lpp and ompA transcripts. Primer extension analysis of the lpp (A) and ompA transcripts using ompA1 (B) and ompA5 (C) primers. The MG1655Δ10 strains, containing the pBAD33 control vector or its derivatives with the relE-like genes, were grown in LB with the appropriate antibiotic at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.6. Toxin expression was then induced by addition of arabinose (1%) for 30 min. Total RNAs were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. Major and minor cleavage sites are indicated by filled and open circles, respectively. FL, full length.

Fig 5.

Location and frequency of RelE-like toxin cleavage sites. A schematic representation of the lpp (A) and ompA (B) transcripts is shown to scale, with each gray box representing 100 nucleotides. Small and large bars represent major and minor cleavage sites, respectively.

Table 2.

Cleavage sites of the RelE-like toxins in the lpp and ompA transcriptsa

| Toxin (bacterial species) | No. of cleavages in: |

Three most frequently cleaved codons in lpp and ompA (relative no.), % |

% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lpp | ompA | lpp and ompA | Codon 1 | Codon 2 | Codon 3 | ||

| RelEK-12 (E. coli K-12) | 33 | 35 | 68 | CAG (11/15), 73 | CUG (10/27), 37 | GCG (4/4), 100 | 37 |

| RelEO157 (E. coli O157:H7) | 19 | 27 | 46 | CUG (18/27), 67 | CAG (7/15), 47 | AUG (5/9), 27 | 65 |

| RelERpa (R. palustris) | 14 | 41 | 55 | CAG (15/15), 100 | AAA (11/18), 61 | CCG (6/12), 50 | 58 |

| RelENsp (Nostoc sp.) | 8 | 33 | 41 | AAA (11/18), 61 | GCA (7/13), 54 | GAA (6/8), 75 | 59 |

| RelESme (S. meliloti) | 11 | 11 | 22 | CAG (7/15), 47 | AAA (4/18), 22 | AUG (3/9), 33 | 63 |

| RelETde (T. denticola) | 1 | 4 | 5 | AAA (2/18), 11 | CCA (1/3), 33 | AAG (1/5), 20 | 80 |

Numbers of sites that are cleaved by the toxins in the E. coli lpp and/or ompA transcripts are indicated. The sequence of the 3 codons that are the most frequently cleaved in the lpp and ompA transcripts is indicated, as well as the number of cleaved codons over the total number of these codons in the 2 transcripts, in relative numbers (in parentheses) and in percentages. The last column (%) represents the proportion of these 3 cleaved codons relative to the total number of cuts mediated by the toxins. In boldface are the codons that are common to different toxins.

RelEK-12 generates 33 cleavages in the lpp mRNA (28 major and 5 minor cleavages) and 35 in ompA (18 major and 17 minor cleavages) (Fig. 4, 5, and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). RelEK-12 cleaves the lpp mRNA throughout the full-length sequence, while the ompA mRNA is preferentially cleaved in the 5′ region. Cleavages occur preferentially between the second and third nucleotide (61%) and mostly upstream of a purine (70%). Among these, 74% occur upstream of a G. The 3 codons most frequently cleaved (CAG, glutamine; CUG, leucine; and GCG, alanine) represent 37% of the sites cleaved by RelEK-12 (Table 2).

While the cleavage pattern of lpp by RelEO157 is similar to that of RelEK-12 (i.e., throughout the mRNA), the cleavage pattern of ompA is different (Fig. 4, 5, and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Only minor cleavages were detected in the 5′ end of ompA, with most of them occurring after the first 200 bp (Fig. 4). Fewer cleavage sites were detected for RelEO157 than for RelEK-12 (46 versus 68). Nineteen cleavages (15 major) were detected in the lpp mRNA and 27 (24 major) in ompA. As for RelEK-12, RelEO157 most frequently cleaves between the second and third nucleotide (90%) and mostly upstream of a G (70%). Among these, 70% occur between a U and a G. The 3 codons most frequently cleaved (CUG, leucine; CAG, glutamine; and AUG codon) represent 65% of the total number of sites cleaved by RelEO157 (Table 2).

The RelERpa toxin cleaves the lpp and ompA mRNAs throughout the full-length sequence, with 14 (11 major) and 41 (30 major) cuts, respectively (Fig. 4, 5, and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Cleavages occur preferentially between the second and third nucleotide (69%) and frequently upstream of purines (93%). The 3 codons most frequently cleaved (CAG, glutamine; AAA lysine; and CCG, proline) represent 58% of the sites cleaved by RelERpa. Note that RelERpa cleaves 100% (15/15) of CAG codons covered by the primer extension experiments (Table 2).

For RelESme, a smaller number of cleavage sites was detected both in lpp (11 cuts, 10 major) and ompA (11 minor cuts) (Fig. 4, 5, and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The cleavage pattern of lpp and ompA by RelESme is quite different from that observed with the other RelE-like toxins, as no cleavage is detected in the 5′ end of the transcripts (first cleavage in lpp at position 77 and 68 in ompA) (Fig. 5). Cleavages occur preferentially between the second and third nucleotide (82%) and before purines (82%). The 3 codons most frequently cleaved (CAG, glutamine; AAA, lysine; and AUG, codon) represent 63% of the total number of cleavage sites (Table 2).

The RelENsp toxin generates 33 (21 major) cleavage sites and 8 major cleavage sites in ompA and lpp mRNAs, respectively (Fig. 4, 5, and Table 2; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The cleavage patterns of lpp and ompA are quite similar, with the mRNAs being cleaved throughout the full-length sequences (Fig. 5). Cleavages occur preferentially between the second and third nucleotide (56%) and the first and second nucleotide (33%). RelENsp cleaves preferentially upstream of an A (71%). The 3 codons most frequently cleaved (GAA, glutamic acid; AAA lysine; and GCA, alanine) represent 59% of the total number of sites cleaved by RelENsp (Table 2).

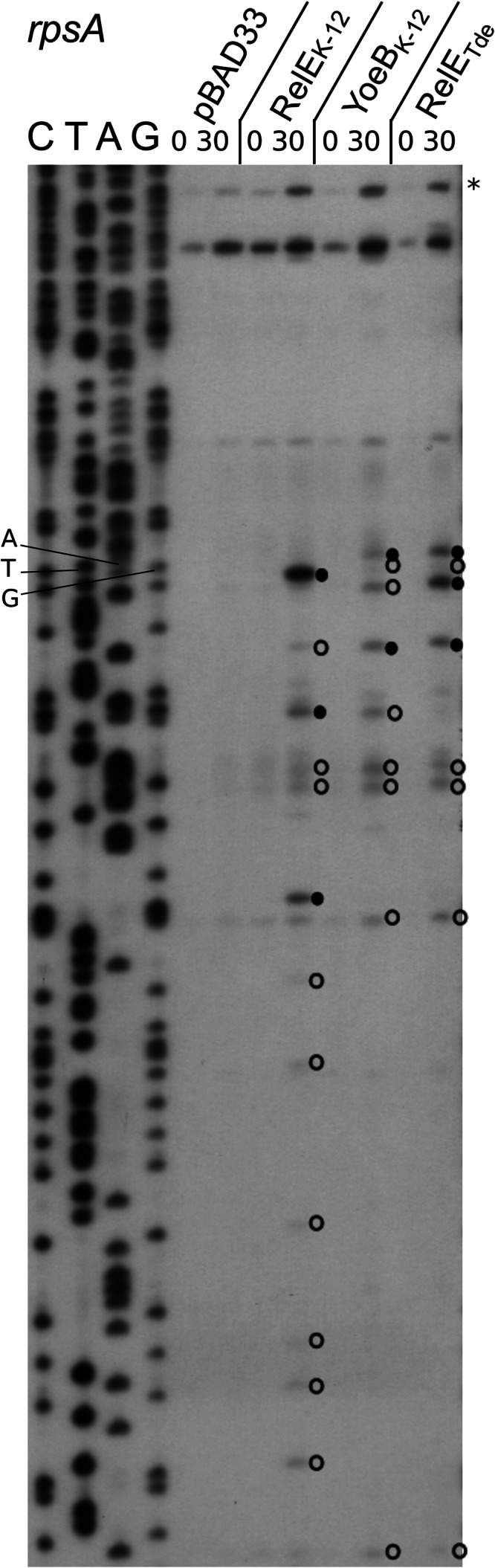

The number of cleavage sites for the RelETde toxin was low compared to those of the other RelE-like toxins (1 cleavage site in the lpp mRNA and 4 in ompA). In both mRNAs, the second AAA codon is cleaved by RelETde. To investigate whether the RelETde activity is sequence or position dependent, we used the rpsA mRNA which encodes an ACU codon in the second position. In this experiment, the YoeBK-12 toxin was included, as it shows a high degree of similarity to RelETde (52% identity, 66% similarity) (Table 1). In addition, YoeBK-12 was previously reported to cleave the second codon of mRNAs (26). Figure 6 shows that overall similar cleavage patterns and specificities are observed in the rpsA mRNA for RelEK-12, RelETde, and YoeBK-12. As observed for YoeBK-12, RelETde cleaves the rpsA mRNA at the second codon, between the second and third nucleotides (upstream of a U). However, in contrast to the other test mRNAs, additional cleavage sites were observed further in the rpsA transcript. Cleavages occurred mainly between the second and third nucleotide (82%) and preferentially upstream of purines (75%). Sequence analysis revealed that the regions upstream (∼12 nucleotides) of the cleavage sites have in common a G-A-rich region presenting similarities to the GAAG Shine-Dalgarno sequence (Fig. 7A). These regions might play a role in cleavage specificity; for instance, by causing ribosome pausing and/or inducing secondary structures (39).

Fig 6.

RelEK-12, YoeBK-12, and RelETde toxin expression leads to similar cleavage patterns on the rpsA transcripts. Primer extension analysis of the rpsA transcript is shown. The MG1655Δ10 strains, containing the pBAD33 control vector or its derivatives expressing the RelEK-12, YoeBK-12, and RelETde toxins, were grown in LB with the appropriate antibiotic at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.6. Toxin expression was then induced by addition of arabinose (1%) for 30 min. Total RNAs were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. Major and minor cleavage sites are indicated by filled and open circles, respectively. The asterisk indicates the full-length transcript from the rpsA3 promoter (41).

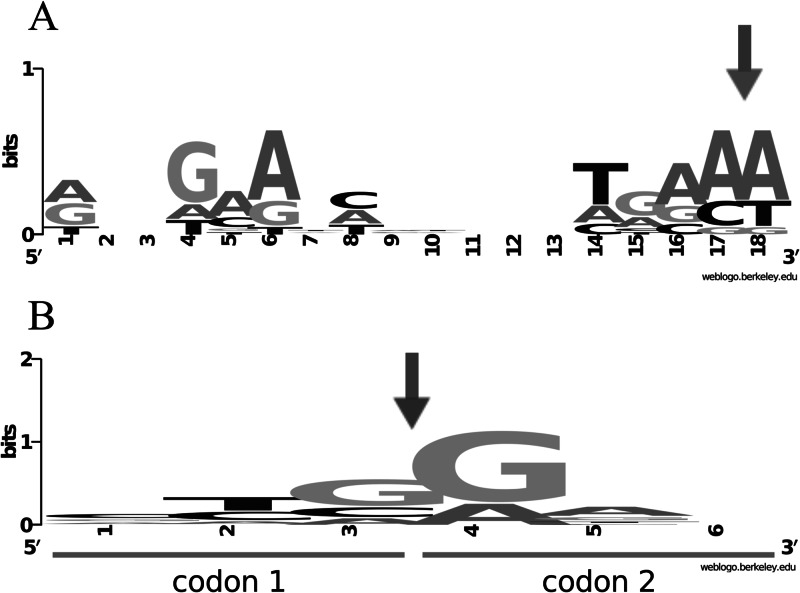

Fig 7.

Consensus sequences around the cleavage sites of the RelETde and RelEMav toxins. (A) Conserved motif upstream of the RelETde cleavage site. The A/GXXGAAXC/A motif is conserved around 12 nucleotides upstream of the RelETde cleavage site (arrow). Logo sequences were constructed using a web-based application (weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi). (B) The RelEMav toxin cleaves preferentially between codons ending and starting with guanines. The cleavage site is represented by an arrow. The upstream codon (codon 1) and the downstream codon (codon 2), as well as the nucleotide position (1, 2, and 3 in codon 1 and 4, 5, and 6 in codon 2), are indicated.

Cleavage by RelEMav presents some specific features (Fig. 4 and 5; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). While the lpp mRNA is cleaved regularly (17 cleavages, 11 major), ompA is preferentially cleaved in the 3′-end region (22 cleavages, 16 major). Only very minor cleavages were observed in the mRNA regions covered by ompA1 and ompA2 primers (covering the 5′ end of the ompA mRNA). In addition, although preferentially cleaving upstream of a G, RelEMav cleaves preferentially between codons (90%) (Fig. 7B).

DISCUSSION

This work highlights the general conservation of molecular mechanisms used by the members of the RelE family of type II toxin. Although originating from distantly related bacterial species and sharing low amino acid sequence similarities, the toxins characterized in this work are mRNA interferases cleaving RNA in a translation-dependent manner. To determine cleavage specificity, primer extension experiments upon RelE-like toxin overexpression were performed in an MG1655 strain deleted of the 10 well-characterized type II systems. We sought to avoid secondary cleavage sites from endogenous type II toxins, although we cannot rule out the contribution of other or unknown endoribonucleases. Our data show that RelE-like toxins do not cleave at specific codons but rather exhibit a trend to cleave upstream of purines and between the second and third positions of codons, which is similar to the activity of the canonical RelEK-12 toxin.

Using the highly expressed ompA and lpp as an mRNA test, we found that these toxins appear to preferentially cleave in vivo at codons that are abundant in bacterial genomes. Note that in vitro analyses using purified toxins and translational complexes will be needed to correlate translation rate and cleavage specificity using artificial mRNAs containing rare codons. Nevertheless, our data show that RelEK-12 preferentially cleaves the glutamine CAG, the leucine CUG, and the alanine GCG codons, as described before (Table 3) (17). Considering these 3 preferential cleavage sites (representing only 37% of the RelEK-12-mediated cuts) and their prevalence in the E. coli genome (117.3/1,000 codons; Table 3), and assuming that these codons are efficiently cleaved, the initial cleavage rate for RelEK-12 is one cleavage every 9 nucleotides. This estimation is similar for the other RelE-like toxins (RelEO157 and RelENsp every 10 nucleotides, and RelERpa every 14). Regarding RelEMav, target codons are also well represented, since it preferentially cleaves before codons starting with G (Fig. 7). Thus, the relaxed specificity of these RelE-like toxins allow them to be quite efficient and quite broad in terms of substrates. Interestingly, we observed that some codons are cleaved by different RelE-like toxins (Table 3). For instance, the CAG glutamine codon is cleaved by RelEK-12, RelEO157, RelERpa, and RelESme. The AAA lysine codon is also cleaved by RelERpa, RelENsp, RelESme, and RelETde (Table 3). This codon is generally found at the second position of highly expressed mRNAs (40).

Table 3.

Most frequently cleaved codons and their occurrence in bacterial genomesa

| Toxin (bacterial species) | Most frequently cleaved codons and their occurrence (0/00) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total | |

| RelEK-12 (E. coli K-12) | CUG (53.8) | GCG (34.3) | CAG (29.2) | 117.3 |

| RelEO157 (E. coli O157:H7) | CUG (51.4) | CAG (29.5) | AUG (24.7) | 105.6 |

| RelERpa (R. palustris) | CCG (37.6) | CAG (26.5) | AAA (7.3) | 71.4 |

| RelENsp (Nostoc sp.) | GAA (46.5) | AAA (34.5) | GCA (22.6) | 103.6 |

| RelESme (S. meliloti) | AUG (22.2) | CAG (24.9) | AAA (6.7) | 53.8 |

| RelETde (T. denticola) | AAA (60.6) | AAG (25.6) | CCA (2.7) | 89.2 |

The 3 most frequently cleaved codons were determined in the lpp and ompA transcripts (Table 2). The occurrence of these codons is indicated in frequency per 1,000 codons (0/00). The last column indicates the sum of the prevalence of the 3 most cleaved codons.

Altogether, our in vivo data suggest that these RelE-like toxins are active and able to exert their function(s) in a large variety of bacterial species. Considering that TA systems are located on mobile genetic elements and that they invade bacterial chromosomes through horizontal gene transfer and subsequent integration as genomic islands, it is likely that a relaxed specificity has been selected by evolution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kenn Gerdes and the members of his laboratory for providing the pSC710 and pSC711 plasmids and for their help with the primer extension experiments.

N.G. is supported by the National Research Fund, Luxembourg (908853). This work was supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRSM-3.4530.04), the Fondation Van Buuren, and the Fonds Brachet.

We thank the scientific community for kindly providing us with genomic DNA and bacterial strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 March 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02266-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arraiano CM, Andrade JM, Domingues S, Guinote IB, Malecki M, Matos RG, Moreira RN, Pobre V, Reis FP, Saramago M, Silva IJ, Viegas SC. 2010. The critical role of RNA processing and degradation in the control of gene expression. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34(5):883–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cascales E, Buchanan SK, Duche D, Kleanthous C, Lloubes R, Postle K, Riley M, Slatin S, Cavard D. 2007. Colicin biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71(1):158–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horvath P, Barrangou R. 2010. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science 327(5962):167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayes F, Van Melderen L. 2011. Toxins-antitoxins: diversity, evolution and function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 46(5):386–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leplae R, Geeraerts D, Hallez R, Guglielmini J, Dreze P, Van Melderen L. 2011. Diversity of bacterial type II toxin-antitoxin systems: a comprehensive search and functional analysis of novel families. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(13):5513–5525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hallez R, Geeraerts D, Sterckx Y, Mine N, Loris R, Van Melderen L. 2010. New toxins homologous to ParE belonging to three-component toxin-antitoxin systems in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 76(3):719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christensen SK, Mikkelsen M, Pedersen K, Gerdes K. 2001. RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98(25):14328–14333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jorgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K. 2009. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 191(4):1191–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Gerdes K. 2006. Two higBA loci in the Vibrio cholerae superintegron encode mRNA cleaving enzymes and can stabilize plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 62(2):397–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Jorgensen MG, Gerdes K. 2010. Three new RelE-homologous mRNA interferases of Escherichia coli differentially induced by environmental stresses. Mol. Microbiol. 75(2):333–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. 2009. Characterization of YafO, an Escherichia coli toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 284(38):25522–25531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hara H, Kato I, Inouye M. 2005. Insights into the mRNA cleavage mechanism by MazF, an mRNA interferase. J. Biol. Chem. 280(5):3143–3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hoeflich KP, Ikura M, Qing G, Inouye M. 2003. MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell 12(4):913–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grady R, Hayes F. 2003. Axe-Txe, a broad-spectrum proteic toxin-antitoxin system specified by a multidrug-resistant, clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Mol. Microbiol. 47(5):1419–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K, Ehrenberg M. 2003. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell 112(1):131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neubauer C, Gao YG, Andersen KR, Dunham CM, Kelley AC, Hentschel J, Gerdes K, Ramakrishnan V, Brodersen DE. 2009. The structural basis for mRNA recognition and cleavage by the ribosome-dependent endonuclease RelE. Cell 139(6):1084–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurley JM, Cruz JW, Ouyang M, Woychik NA. 2011. Bacterial toxin RelE mediates frequent codon-independent mRNA cleavage from the 5′ end of coding regions in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 286(17):14770–14778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li GY, Zhang Y, Inouye M, Ikura M. 2009. Inhibitory mechanism of Escherichia coli RelE-RelB toxin-antitoxin module involves a helix displacement near an mRNA interferase active site. J. Biol. Chem. 284(21):14628–14636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boggild A, Sofos N, Andersen KR, Feddersen A, Easter AD, Passmore LA, Brodersen DE. 2012. The crystal structure of the intact E. coli RelBE toxin-antitoxin complex provides the structural basis for conditional cooperativity. Structure 20(10):1641–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2003. New connections in the prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin network: relationship with the eukaryotic nonsense-mediated RNA decay system. Genome Biol. 4(12):R81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guglielmini J, Van Melderen L. 2011. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: translation inhibitors everywhere. Mob. Genet. Elements 1(4):283–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiang Y, Pogliano J, Helinski DR, Konieczny I. 2002. ParE toxin encoded by the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 is an inhibitor of Escherichia coli gyrase. Mol. Microbiol. 44(4):971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Y, Inouye M. 2009. The inhibitory mechanism of protein synthesis by YoeB, an Escherichia coli toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 284(11):6627–6638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamaguchi Y, Park JH, Inouye M. 2009. MqsR, a crucial regulator for quorum sensing and biofilm formation, is a GCU-specific mRNA interferase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 284(42):28746–28753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prysak MH, Mozdzierz CJ, Cook AM, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Inouye M, Woychik NA. 2009. Bacterial toxin YafQ is an endoribonuclease that associates with the ribosome and blocks translation elongation through sequence-specific and frame-dependent mRNA cleavage. Mol. Microbiol. 71(5):1071–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kamada K, Hanaoka F. 2005. Conformational change in the catalytic site of the ribonuclease YoeB toxin by YefM antitoxin. Mol. Cell 19(4):497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heaton BE, Herrou J, Blackwell AE, Wysocki VH, Crosson S. 2012. Molecular structure and function of the novel BrnT/BrnA toxin-antitoxin system of Brucella abortus. J. Biol. Chem. 287(15):12098–12110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han KD, Matsuura A, Ahn HC, Kwon AR, Min YH, Park HJ, Won HS, Park SJ, Kim DY, Lee BJ. 2011. Functional identification of toxin-antitoxin molecules from Helicobacter pylori 26695 and structural elucidation of the molecular interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 286(6):4842–4853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hurley JM, Woychik NA. 2009. Bacterial toxin HigB associates with ribosomes and mediates translation-dependent mRNA cleavage at A-rich sites. J. Biol. Chem. 284(28):18605–18613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garcia-Pino A, Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Wyns L, Yarmolinsky M, Magnuson RD, Gerdes K, Loris R. 2008. Doc of prophage P1 is inhibited by its antitoxin partner Phd through fold complementation. J. Biol. Chem. 283(45):30821–30827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winther KS, Gerdes K. 2009. Ectopic production of VapCs from Enterobacteria inhibits translation and trans-activates YoeB mRNA interferase. Mol. Microbiol. 72(4):918–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Van Melderen L. 2007. What is the benefit to Escherichia coli of having multiple toxin-antitoxin systems in its genome? J. Bacteriol. 189(17):6101–6108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97(12):6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158(1):9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Christensen SK, Gerdes K. 2003. RelE toxins from bacteria and Archaea cleave mRNAs on translating ribosomes, which are rescued by tmRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 48(5):1389–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Masse E, Escorcia FE, Gottesman S. 2003. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 17(19):2374–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Armalyte J, Jurenaite M, Beinoraviciute G, Teiserskas J, Suziedeliene E. 2012. Characterization of Escherichia coli dinJ-yafQ toxin-antitoxin system using insights from mutagenesis data. J. Bacteriol. 194(6):1523–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christensen SK, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Gottesman S, Gerdes K, Van Melderen L. 2004. Overproduction of the Lon protease triggers inhibition of translation in Escherichia coli: involvement of the yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin system. Mol. Microbiol. 51(6):1705–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wen JD, Lancaster L, Hodges C, Zeri AC, Yoshimura SH, Noller HF, Bustamante C, Tinoco I. 2008. Following translation by single ribosomes one codon at a time. Nature 452(7187):598–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brock JE, Paz RL, Cottle P, Janssen GR. 2007. Naturally occurring adenines within mRNA coding sequences affect ribosome binding and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189(2):501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lemke JJ, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Burgos HL, Hedberg G, Ross W, Gourse RL. 2011. Direct regulation of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein promoters by the transcription factors ppGpp and DksA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108(14):5712–5717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.