Abstract

We report the structural characterization of the first antibody identified to cross-neutralize multiple subtypes of influenza A viruses. The crystal structure of mouse antibody C179 bound to the pandemic 1957 H2N2 hemagglutinin (HA) reveals that it targets an epitope on the HA stem similar to those targeted by the recently identified human broadly neutralizing antibodies. C179 also inhibits the low-pH conformational change of the HA but uses a different angle of approach and both heavy and light chains.

TEXT

Influenza viruses cause respiratory infections in humans, resulting in severe disease in millions of individuals annually and high mortality during pandemics, such as the 1918 “Spanish Flu” pandemic. Entry of influenza viruses is mediated by its major surface glycoprotein hemagglutinin (HA), making it the primary target for neutralizing antibodies (Abs) and vaccine design. Tremendous effort has been invested in isolating and structurally characterizing human antibodies to the highly conserved membrane-proximal “stem” region of HA (1–6). Many of these antibodies against the stem appear to inhibit viral entry by preventing the pH-induced conformational change that leads to fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes. A structural understanding of these broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) and their epitopes is now providing critical information for design of effective and more broadly applicable vaccines.

Antibody C179, isolated in 1993 from a mouse immunized with an H2N2 virus (7), was the first anti-HA monoclonal Ab (MAb) reported to cross-neutralize multiple influenza virus subtypes, including H1, H2, H5, H6, and H9 viruses (7–10). Escape mutations were selected by C179 in the HA stem region, and C179 neutralized virus by inhibiting the fusion process, suggesting that C179 recognizes an epitope on the conserved membrane-proximal stem region of the HA (7). Despite decades of study and widespread use as a reference antibody, the molecular details of the C179 epitope have remained obscure.

C179 Fab and HAs were cloned, expressed, and purified as described previously (2). Briefly, C179 Fab was cloned in a pFastBac Dual vector with a C-terminal His6 tag fused to the heavy chain. The C179 sequence was extracted from the sequence specified by U.S. patent 5684146 (11). Fab was produced by baculovirus infection of Hi5 insect cells and purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) and MonoS chromatography and then gel filtration. HAs were cloned in a pFastBac vector with an N-terminal gp67 signal peptide and a C-terminal biotinylation site, thrombin cleavage site, T4 fibritin trimerization domain, and His6 tag. HA0 protein was expressed by infecting suspension cultures of Hi5 cells and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. For crystallography, HA0 was digested with trypsin to produce uniformly cleaved HA1 and HA2 and to remove the trimerization domain and His6 tag. HA was further purified by anion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. For binding studies, HA0 was biotinylated with biotin ligase (BirA) and purified by gel filtration.

After expressing and purifying C179 and various HAs, we used the following methods to analyze the C179 interactions and activity and determine its crystal structure in complex with the H2 HA. Dissociation constant (Kd) values (Fig. 1) were determined by biolayer interferometry (BLI) using an Octet Red instrument (ForteBio, Inc.) as previously described (2). Biotinylated HAs at ∼10 to 50 μg/ml in 1× kinetics buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] [pH 7.4], 0.01% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 0.002% Tween 20) were loaded onto streptavidin-coated biosensors and incubated with various concentrations of C179 (up to 1 μM).

Fig 1.

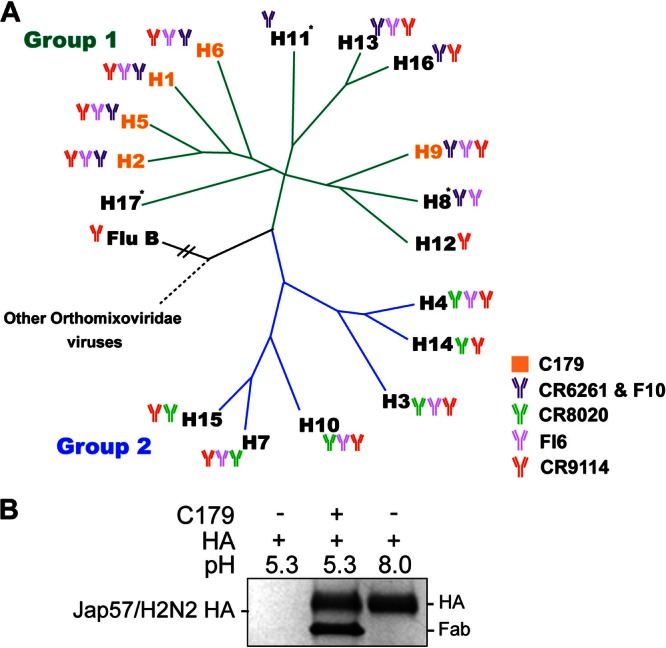

In vitro binding and neutralization mechanism of C179. (A) Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships between the 17 HA subtypes of influenza A virus, divided into two major lineages (groups 1 and 2). C179 binds multiple group 1 subtypes (orange text). Subtypes neutralized by the other stem bnAbs are denoted. The phylogenetic distance to influenza B virus is not to scale. *, HA not tested for binding. (B) C179 inhibits the HA pH-induced conformational change that drives membrane fusion. Exposure to low pH converts Jap57/H2 HA to a postfusion state that is sensitive to trypsin digestion (lane 1). Preincubation with C179 prevents this conversion, retaining the HA in the protease-resistant, prefusion form (lane 2).

For Fab-HA complex formation, C179 Fab was added to Jap57/H2 HA at a molar ratio of ∼3.2:1 to saturate all C179 binding sites on the HA trimer and the reaction mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. Saturated complexes were purified from unbound Fab by gel filtration and concentrated to ∼10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl–(pH 8.0)–50 mM NaCl. C179-Jap57/H2 HA crystals were grown by sitting-drop vapor diffusion at 20°C by mixing 0.5 μl of concentrated protein sample with 0.5 μl of mother liquor (2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]), and crystals appeared after ∼1 month. The resulting crystals were cryoprotected in well solution supplemented with increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol (5% steps, 5 min/step), to a final concentration of 35% and then flash cooled and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data were collected at beamline 11-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), indexed in space group P212121, integrated using XDS (12), and scaled using XPREP (Bruker). The structure was solved by molecular replacement to 2.9-Å resolution using Phaser (13). Rigid-body refinement, simulated annealing, and restrained refinement (including translation-libration-screw [TLS] refinement, with one group for HA1, one for HA2, and one for each Ig domain) were carried out in Phenix (14). The models were rebuilt and adjusted using Coot (15).

Hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts were calculated using HBPLUS and CONTACSYM, respectively (16, 17). Buried surface area was calculated with MS (18). MacPyMol (DeLano Scientific) was used to render structure figures. Kabat numbering was applied to the Fab data using the Abnum server (19). The final coordinates were validated using the JCSG quality control server (v2.7), which includes Molprobity (20).

All full-length, nonredundant, and non-laboratory strain influenza A virus HA sequences were downloaded (accession date 11 April 2012) from the NCBI FLU database (21). The 13,627 sequences, encompassing all 17 influenza A virus subtypes, were aligned using MUSCLE (22) and analyzed using GCG (Accelrys) and custom shell scripts (available upon request). Residues were considered conserved when substitutions were restricted to other amino acids in the same group: (i) Asp, Asn, Glu, and Gln (negatively charged or isosteric polar substitutions); (ii) Val, Ile, Leu, and Met (small hydrophobic); (iii) Phe and Tyr (aromatic); and (iv) Ser and Thr (small polar or hydroxyl). The values reported for percent conservation are the numbers of sequences that were identical or had a conservative change at a position divided by the total number of sequences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Impact of epitope variation on C179 bindinga

Dissociation constants (Kd) and sequences corresponding to C179 contact residues are shown for different strains and subtypes. Residues that differ from the HA consensus sequence are in black boxes. N.B., no binding.

b Presence (+) or absence (−) of a glycosylation site at HA1 position 38.

A protease susceptibility assay was performed as described previously (7). For Jap57/H2 HA, each reaction mixture contained ∼2.5 μg HA. Trypsin was added to all HA samples except the control at a final ratio of 1:10 by mass.

Using these above methods, we obtained the following results. To further explore the breadth of neutralization of C179, we used biolayer interferometry to test Fab C179 binding to a large panel of HAs, including representatives of most of the 17 HA subtypes (H1 to H17) of influenza A virus as well as the two distinct lineages from influenza B virus (Fig. 1A). In accord with its previously reported neutralization breadth, Fab C179 binds to several influenza A virus group 1 subtypes, including H1, H2, H5, H6, and H9, with high to intermediate affinity (Kd ∼2 to 200 nM) (Table 1). No binding to any influenza A virus group 2 (Table 1) or influenza B virus (B/Florida/4/2006 and B/Malaysia/2506/2004) HAs tested was detected.

C179 has no effect on virus attachment but neutralizes the virus by inhibiting the fusion process (7). Thus, we assayed its ability to block the low pH-induced conformational change in HA (2) (Fig. 1B). Exposure to low pH converts HA to a postfusion form, rendering it sensitive to trypsin digestion. Preincubation of Jap57/H2 HA with C179 retained the HA in its trypsin-resistant, prefusion state, indicating that C179 likely prevents membrane fusion and viral entry by inhibiting the fusogenic conformational change, as observed for other human antibodies against the stem (1–4). Other mechanisms, such as Fc-mediated effector functions, could also play a critical role in vivo in the protective mechanism of this antibody (2, 23).

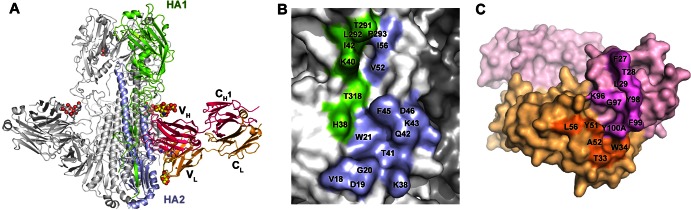

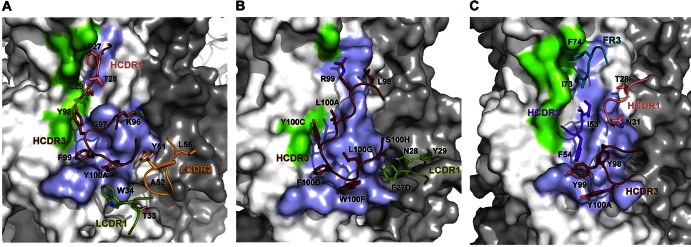

To elucidate the molecular basis for C179 cross-reactivity, we determined the crystal structure of Fab C179 in complex with the HA from a pandemic H2N2 influenza virus [A/Japan/305/1957 (H2N2); Jap57/H2] at 2.90-Å resolution (Fig. 2A and Table 2). The Jap57/H2 HA structure is very similar to other H2 structures (25, 26) and consists of a membrane-distal receptor binding domain (HA1, “head”) atop a largely α-helical membrane fusion region (HA2 and some HA1, “stem”). One homotrimeric HA is present in the asymmetric unit, with one Fab bound per HA protomer. C179 binds the HA stem (Fig. 2 and 3A), recognizing an epitope similar to those corresponding to the previously characterized bnAbs CR6261, F10, CR9114, and FI6 (1–3, 5). The epitope consists of residues from the N- and C-terminal regions of HA1 (residues 38, 40, 42, 291 to 293, and 318) and the N-terminal portion of HA2 (residues 18 to 21, 38, 41 to 43, 45, 46, 52, and 56), including helix A. Earlier mapping (7, 10, 27) of the C179 epitope to HA1 residues 318 to 322 and HA2 residues 47 to 58 includes some regions that we observed interacting in the crystal structure. However, we identified many additional residues that are essential for antibody recognition (Fig. 2B). C179 buries a total of ∼1,460 Å2 at the interface with HA (740 Å2 for HA and 720 Å2 for Fab) (Fig. 2B and C). Unlike VH1-69 antibodies, such as CR6261, F10, and CR9114, which bind the stem using only their heavy chains, C179 uses both Fab chains (heavy and light) to bind HA. The C179 heavy chain contributes 72% of the Fab buried surface area, similar to other antibodies against protein antigens. Thus, C179 further demonstrates that heavy-chain restricted binding is not strictly required to achieve broad activity against group 1 HAs and suggests that some human bnAbs may employ a C179-like binding mode. Indeed, while VH1-69 antibodies dominate the response against the stem in humans, several other V genes are also found with high frequency among clones with similar cross-reactivity, such as VH3-30, which is used in bnAb FI6 (28), indicating that it may be possible to elicit a C179-like antibody response in humans. In contrast to the generaly similar binding orientations of bnAbs CR6261, CR9114, and F10, C179 is rotated ∼45° relative to the epitope on HA and uses an angle of approach that is more similar to that of FI6 despite a markedly different binding interaction (Fig. 3). The C179 VH domain binds using heavy-chain complementarity-determining region 1 (HCDR1) and HCDR3 (Fig. 3A), which coalesce to form a linear cluster of hydrophobic residues that create a complementary hydrophobic surface for interaction with a hydrophobic groove in the HA delimited by the fusion peptide, helix A, and the N-terminal segment of HA1. HCDR1, via Phe27, Thr28, and Leu29, inserts into the membrane-distal end of the hydrophobic groove just below the HA head and contacts HA1 Lys40, Ile42, Thr291, Leu292, and Pro293 along with HA2 Val52, and Ile56. Three large hydrophobic residues at the tip of HCDR3, Tyr98, Phe99, and Tyr100A, interact with a second hydrophobic patch on the HA as well as with surrounding polar residues, including HA1 Thr318 and His38 and HA2 Val18, Asp19, Gly20, Trp21, Lys38, Thr41, Gln42, and Phe45. Corresponding HCDR3 interactions were observed in the FI6-HA complexes where C179 and FI6 similarly insert two aromatic side chains from their HCDR3 (Tyr98C179and Tyr100CFI6 and Phe99C179and Phe100DFI6) into the hydrophobic groove. In the VH1-69 antibodies, two hydrophobic residues from the signature HCDR2 insert into this same groove (e.g., Ile53 and Phe54 in CR6261 and CR9114) (2, 3). In C179, Tyr98 also makes hydrogen bonds with the side chain of HA1 Thr318 (1). The light chain also contributes to the hydrophobic interactions where LCDR1 Trp34, close to the linear cluster of hydrophobic residues on HCDR3, interacts with the aliphatic portions of HA2 Lys38 and Asp19 (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

C179 binds an epitope in the HA stem. (A) Crystal structure of Jap57/H2 in complex with the Fab from mouse monoclonal antibody C179 (PDB ID no. 4HLZ). One HA/Fab protomer of the trimeric complex is colored with HA1 in green, HA2 in light blue, Fab heavy chain in magenta, Fab light chain in orange, and N-linked glycans as spheres colored by atom type. The two other protomers are colored in gray. (B) Footprint of C179 on the HA highlighting HA residues interacting with C179 with HA1 residues in green and HA2 residues in light blue. (C) Footprint of HA on C179 with the heavy chain interacting surfaces in magenta and the light chain interacting surfaces in orange; Fab residues contacting the HA are labeled.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statisticsa

| Parameter(s) | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| Data collection | C179-A/Japan/305/1957 H2 complex |

| Beamline | SSRL 11-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.03317 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters | a = 136.58 Å, b = 150.78 Å, c = 217.78 Å |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.90 (2.97–2.90) |

| No. of observations | 740,693 |

| No. of unique reflections | 100,115 (9,529) |

| Redundancy | 7.3 (5.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| <I/σI> | 9.8 (1.2) |

| Rsymb | 0.18 (0.91) |

| Rpimb | 0.07 (0.40) |

| Zac | 3 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.90 |

| No. of reflections (work) | 99,399 |

| No. of reflections (test) | 4,964 |

| Rcryst (%)d | 22.7 |

| Rfree (%)e | 28.4 |

| Average B value (Å2) | 102 |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 86 |

| No. of protein atoms | 21,520 |

| No. of carbohydrate atoms | 252 |

| No. of water molecules | 0 |

| RMSD from ideal geometry | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.35 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)f | |

| Favored | 95.2 |

| Outliers | 0.07 |

| PDB ID | 4HLZ |

Numbers in parentheses in column 2 refer to the highest-resolution shell. RMSD, root mean square deviation; PDB ID, Protein Data Bank identification number.

Rsym = ΣhklΣi | Ihkl,i − <Ihkl> |/ΣhklΣiIhkl,I and Rpim = Σhkl [1/(n − 1)]1/2Σi | Ihkl,i − <Ihkl> |/ΣhklΣiIhkl,I, where Ihkl,i is the scaled intensity of the ith measurement of reflections h, k, and l, <Ihkl> is the average intensity for that reflection, and n is the redundancy (24). Note that despite the high Rsym in the highest-resolution shell, the high redundancy enables the average F values to be well determined (assuming measurement errors are randomly distributed), as reflected by the redundancy-independent measurement of the quality of intensity measurements Rpim.

Za, number of HA monomer-Fab complexes per crystallographic asymmetric unit.

Rcryst = Σhkl | Fo − Fc |/Σhkl | Fo | × 100.

Rfree was calculated described as for Rcryst but on a test set comprising 5% of the data excluded from the refinement data.

Calculated using Molprobity (20).

Fig 3.

C179 interactions with Jap57/H2 HA and comparison with FI6 and CR9114. (A) Surface representation of the C179 epitope on the HA stem with side chains of interacting residues from C179 shown and colored by CDR loop. HCDR1, pink; HCDR3, brown; LCDR1, green; LCDR2, orange. (B and C) Similar representation of FI6 (VH3-30) and CR9114 (VH1-69) in complex with H1 HA (PDB 3ZTN) and H5 HA (PDB 4FQI), respectively. Colors are as described for panel A, with HCDR2 in purple and FR3 in cyan.

Whereas C179 is able to tolerate a wide range of natural variation (Table 1), two substitutions (HA1 Thr318Lys and HA2 Val52Glu) in the H1 HA epitope have been shown to abrogate neutralization by C179 (7). In order to further investigate how these mutations lead to virus escape, we introduced these changes into the HA of A/South Carolina/1/1918 (H1N1) virus and assayed their effect on C179 binding. C179 binding to both of these mutants is undetectable under our assay conditions (Kd>∼10 μM, data not shown). However, the Thr318Lys escape variant is not present in any circulating HA subtypes, but such a mutation could lead to a steric clash with Tyr98. The second of these escape mutants, HA2 Val52Glu, is extremely rare in most subtypes and appears in only two of the 13,627 influenza A virus sequences (one H1N1 virus and one H2N2 virus) in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Flu database (21). The C179 HCDR1 conformation precludes accommodation of large residues at HA2 position 52. Isolate-specific HA variation in residues participating in, or proximal to, the epitope may also influence C179 interactions with certain HAs of the H12, H13, or H16 subtypes (Table 1).

As noted previously (1, 2, 3, 5), group-specific and subtype-specific differences at position 111 in HA2 (His in group 1, Thr/Ala in group 2) result in subtly different conformations of the conserved HA2 Trp21 indole side chain, affecting the ability of Trp21 to make favorable interactions with HCDR2 hot spot residues Phe54 and Phe55 in CR6261 and F10, respectively (3, 5). C179 makes a similar interaction with Trp21 using Phe99 at the tip of HCDR3 (Fig. 3A). To understand why C179 does not bind group 2 HAs, we tested the effect of the HA2 His111Thr mutation on an H1N1 HA and found that this mutation abrogates C179 binding.

Our analysis of the crystal structure of C179 in complex with Jap57/H2 reveals that C179 binds an epitope similar to those of the recently characterized human antibodies against the HA stem, despite being isolated from a mouse nearly 2 decades ago. Only in recent years has there been an upsurge of interest in broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza virus that has renewed hope for a universal or at least a broader-spectrum influenza vaccine (1–6, 29–31). Interestingly, while clear similarities in the binding of various VH1-69 stem antibodies (CR9114/CR6261/F10) and some differences with VH3-30 (FI6) antibodies from humans are observed, the mouse C179 antibody presents yet another solution with respect to the cross-neutralization of group 1 influenza viruses. The challenge now is to use all of the useful information provided by the structures of these diverse bnAbs in complex with HA to design immunogens or small molecules that target these epitopes and inhibit virus entry and replication. As the number of bnAb structures increases, trends in recognition of the stem epitopes are emerging, including common features of recognition of the hydrophobic groove on the HA stem and the ability of Trp21 to modulate cross-group reactivity. The additional information obtained here from C179 may therefore aid in vaccine design as well as in improvement of small-protein fusion inhibitors, such as HB36 and F-HB80.4 (31, 32), and perhaps even small molecules targeting the stem region.

Protein structure accession number.

The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB; www.pdb.org) (PBD identification [ID] code 4HLZ).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Lars Hangartner for stimulating discussions on C179 and thank Henry Tien of the Robotics Core at the Joint Center for Structural Genomics for automated crystal screening. Portions of this research were carried out on Beamline 11-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

The Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by NIH, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program (P41RR001209), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The work was supported in part by NIH grants AI058113 and AI099275 (I.A.W.).

This is manuscript 21953 from The Scripps Research Institute.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Corti D, Voss J, Gamblin SJ, Codoni G, Macagno A, Jarrossay D, Vachieri SG, Pinna D, Minola A, Vanzetta F, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Agatic G, Bianchi S, Giacchetto-Sasselli I, Calder L, Sallusto F, Collins P, Haire LF, Temperton N, Langedijk JP, Skehel JJ, Lanzavecchia A. 2011. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science 333:850–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dreyfus C, Laursen NS, Kwaks T, Zuijdgeest D, Khayat R, Ekiert DC, Lee JH, Metlagel Z, Bujny MV, Jongeneelen M, van der Vlugt R, Lamrani M, Korse HJ, Geelen E, Sahin O, Sieuwerts M, Brakenhoff JP, Vogels R, Li OT, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J, Friesen RH. 2012. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science 337:1343–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, Friesen RH, Jongeneelen M, Throsby M, Goudsmit J, Wilson IA. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ekiert DC, Friesen RH, Bhabha G, Kwaks T, Jongeneelen M, Yu W, Ophorst C, Cox F, Korse HJ, Brandenburg B, Vogels R, Brakenhoff JP, Kompier R, Koldijk MH, Cornelissen LA, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J. 2011. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science 333:843–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, Wei G, Aird D, Chen LM, Santelli E, Stec B, Cadwell G, Ali M, Wan H, Murakami A, Yammanuru A, Han T, Cox NJ, Bankston LA, Donis RO, Liddington RC, Marasco WA. 2009. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat. Struct. Biol. 16:265–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kashyap AK, Steel J, Rubrum A, Estelles A, Briante R, Ilyushina NA, Xu L, Swale RE, Faynboym AM, Foreman PK, Horowitz M, Horowitz L, Webby R, Palese P, Lerner RA, Bhatt RR. 2010. Protection from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza by an antibody from combinatorial survivor-based libraries. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. 1993. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J. Virol. 67:2552–2558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takara Bio Inc Monoclonal antibody C179 product information sheet. Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan: http://catalog.takara-bio.co.jp/en/PDFFiles/M145_DS_e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sakabe S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Horimoto T, Nidom CA, Le MQ, Takano R, Kubota-Koketsu R, Okuno Y, Ozawa M, Kawaoka Y. 2010. A cross-reactive neutralizing monoclonal antibody protects mice from H5N1 and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Antiviral Res. 88:249–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smirnov YA, Lipatov AS, Gitelman AK, Okuno Y, Van Beek R, Osterhaus AD, Claas EC. 1999. An epitope shared by the hemagglutinins of H1, H2, H5, and H6 subtypes of influenza A virus. Acta Virol. 43:237–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kato I, Okuno Y, Oshima A, Takabatake T, Yoshioka H. November 1997. DNA coding for variable region to human influenza A type virus. US patent 5684146

- 12. Kabsch W. 2010. Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40:658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDonald IK, Thornton JM. 1994. Satisfying hydrogen bonding potential in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 238:777–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheriff S, Hendrickson WA, Smith JL. 1987. Structure of myohemerythrin in the azidomet state at 1.7/1.3 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 197:273–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Connolly M. 1983. Analytical molecular surface calculation. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 16:548–558 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abhinandan KR, Martin AC. 2008. Analysis and improvements to Kabat and structurally correct numbering of antibody variable domains. Mol. Immunol. 45:3832–3839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 2010. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bao Y, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Kiryutin B, Zaslavsky L, Tatusova T, Ostell J, Lipman D. 2008. The influenza virus resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J. Virol. 82:596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hessell AJ, Hangartner L, Hunter M, Havenith CE, Beurskens FJ, Bakker JM, Lanigan CM, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. 2007. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature 449:101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weiss MS, Hilgenfeld R. 1997. On the use of the merging R factor as a quality indicator for X-ray data. J. Appl. Crystallog. 30:203–205 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu R, McBride R, Paulson JC, Basler CF, Wilson IA. 2010. Structure, receptor binding, and antigenicity of influenza virus hemagglutinins from the 1957 H2N2 pandemic. J. Virol. 84:1715–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu J, Stevens DJ, Haire LF, Walker PA, Coombs PJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2009. Structures of receptor complexes formed by hemagglutinins from the Asian influenza pandemic of 1957. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17175–17180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smirnov YA, Lipatov AS, Gitelman AK, Claas EC, Osterhaus AD. 2000. Prevention and treatment of bronchopneumonia in mice caused by mouse-adapted variant of avian H5N2 influenza A virus using monoclonal antibody against conserved epitope in the HA stem region. Arch. Virol. 145:1733–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI, Mehta A, Razavi B, Del Rio C, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Ali Z, Kaur K, Andrews S, Amara RR, Wang Y, Das SR, O'Donnell CD, Yewdell JW, Subbarao K, Marasco WA, Mulligan MJ, Compans R, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2011. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:181–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ekiert DC, Kashyap AK, Steel J, Rubrum A, Bhabha G, Khayat R, Lee JH, Dillon MA, O'Neil RE, Faynboym AM, Horowitz M, Horowitz L, Ward AB, Palese P, Webby R, Lerner RA, Bhatt RR, Wilson IA. 2012. Cross-neutralization of influenza A viruses mediated by a single antibody loop. Nature 489:526–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bommakanti G, Citron MP, Hepler RW, Callahan C, Heidecker GJ, Najar TA, Lu X, Joyce JG, Shiver JW, Casimiro DR, ter Meulen J, Liang X, Varadarajan R. 2010. Design of an HA2-based Escherichia coli expressed influenza immunogen that protects mice from pathogenic challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13701–13706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whitehead TA, Chevalier A, Song Y, Dreyfus C, Fleishman SJ, De Mattos C, Myers CA, Kamisetty H, Blair P, Wilson IA, Baker D. 2012. Optimization of affinity, specificity and function of designed influenza inhibitors using deep sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 30:543–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fleishman SJ, Whitehead TA, Ekiert DC, Dreyfus C, Corn JE, Strauch EM, Wilson IA, Baker D. 2011. Computational design of proteins targeting the conserved stem region of influenza hemagglutinin. Science 332:816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]