Abstract

Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) infects a range of human cell types with high efficiency. Upon infection, the viral genome can persist as high-copy-number, circular, nonintegrated episomes that segregate to progeny cells upon division. This allows HVS-based vectors to stably transduce a dividing cell population and provide sustained transgene expression in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the HVS episome is able to persist and provide prolonged transgene expression during in vitro differentiation of mouse and human hemopoietic progenitor cells. Together, these properties are advantageous for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, whereby stem cell-like cells are generated from adult somatic cells by exogenous expression of specific reprogramming factors. Here we assess the potential of HVS-based vectors for the generation of induced pluripotent cancer stem-like cells (iPCs). We demonstrate that HVS-based exogenous delivery of Oct4, Nanog, and Lin28 can reprogram the Ewing's sarcoma family tumor cell line A673 to produce stem cell-like colonies that can grow under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. Further analysis of the HVS-derived putative iPCs showed some degree of reprogramming into a stem cell-like state. Specifically, the putative iPCs had a number of embryonic stem cell characteristics, staining positive for alkaline phosphatase and SSEA4, in addition to expressing elevated levels of pluripotent marker genes involved in proliferation and self-renewal. However, differentiation trials suggest that although the HVS-derived putative iPCs are capable of differentiation toward the ectodermal lineage, they do not exhibit pluripotency. Therefore, they are hereby termed induced multipotent cancer cells.

INTRODUCTION

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology involves the generation of stem cell-like cells from adult somatic cells by the exogenous expression of specific reprogramming factors (1). This technology therefore has the potential to generate stem cells that are patient specific and ethically sourced and is of great interest in stem cell-based therapies. Aside from their therapeutic potential, iPSCs also provide an excellent model for the study of development and disease progression (2). The first example of iPSC generation showed that mouse embryonic fibroblasts could be reprogrammed to closely resemble embryonic stem cells (ESCs) by the exogenous expression of only four genes, those for Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc (1). However, the genes for Klf4 and Myc are potent oncogenes capable of disrupting the host cell cycle and driving uncontrolled proliferation; therefore, the genes for Lin28 and Nanog can now be used to replace those for Klf4 and Myc in iPSC generation (3). Furthermore, the requirement for exogenous Sox2 expression can be circumvented by reprogramming cells that endogenously express Sox2, such as neural stem cells (NSCs) (4).

An interesting application of iPSC technology is reprogramming of somatic cancer cells to induced pluripotent cancer stem-like cells (iPCs) (5, 6). This technology may provide a unique model to study human cancer development in vitro and would also offer a platform for cancer drug screening. Moreover, iPCs could clarify the links among self-renewal, pluripotency, and tumorigenesis and highlight key factors that influence tumor progression.

A number of gene delivery approaches have been assessed for iPSC reprogramming. Retroviral vectors have the advantage of providing prolonged expression of the reprogramming factor transgenes, which is essential for efficient reprogramming. However, retroviruses preferentially integrate into highly expressed regions of the genome and can disrupt normal gene function by causing the overexpression of genes related to proliferation or, alternatively, silence regulatory genes (7). Thus, there have been many attempts to develop safer reprogramming vectors, including the generation of excisable retroviral vectors by Cre/LoxP recombination (8) or piggyBac transposons (9). However, both of these systems leave behind a “footprint” after excision that can still disrupt normal gene function and therefore require very stringent screening processes to ensure that all of the viral DNA has been excised. Alternative gene delivery methods, including adenoviral infection (10), repeated plasmid transfection (11), and cell-permeating recombinant reprogramming factor proteins (12), have had some success, but their efficiency is poor compared to that of retroviral vectors. Recently, however, two nonintegrating gene delivery methods have been developed that show promising results for iPSC production based on the transfection of synthetic mRNA modified to overcome the innate antiviral response (13) or transduction with Sendai virus vectors (14). The Sendai virus system also incorporates temperature-sensitive mutations, allowing the vector to be removed from generated iPSCs at nonpermissive temperatures.

Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) is a gamma-2 herpesvirus originally isolated from the T lymphocytes of the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus), where it causes an asymptomatic infection (15). HVS possesses a number of characteristics that make it a promising gene delivery vector (16, 17). First, its large genome capacity enables the transport of multiple genes to a target cell (18). Furthermore, HVS can efficiently infect and establish a latent persistent infection in a variety of human cell lines, including carcinoma cells and hematopoietic cells, enabling long-term transgene expression (19–21). The viral genome exists as a stable circular episome separate from host DNA, thereby reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis and gene silencing by epigenetic mechanisms. HVS can also persist in dividing cells, as the episomal DNA is able to replicate during latency and is transferred to daughter cells upon cell division via the open reading frame 73 (ORF73) episomal maintenance protein (22–25). The virus has also been shown to efficiently infect and persist in three-dimensional multicellular spheroid cultures, a three-dimensional cell culture system that closely resembles a tumor, in addition to tumor xenografts in vivo (26–28). This has led to the development of HVS as a potential episomal vector for adoptive immunotherapy for infectious and malignant diseases (29–31), cancer therapy (27), rheumatoid arthritis of the joints (32), and inherited and acquired liver diseases (28).

Perhaps of particular interest in regard to iPSC technology is the ability of HVS to persist and provide prolonged transgene expression in differentiating cell populations. This was first demonstrated with totipotent mouse ESCs. Upon infection, the HVS genome was maintained in the presence of selection and had no apparent effect on cell/colony morphology of the transduced mouse ESCs and no virus replication or production was observed. Interestingly, upon in vitro differentiation of these persistently infected mouse ESCs, the HVS genome is stably maintained in terminally differentiated macrophages. Moreover, green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression from the HVS episome was maintained in terminally differentiated macrophages (21). Similar results were also observed upon human hemopoietic progenitor cell differentiation toward the erythroid lineage (33). Therefore, HVS could potentially be capable of maintaining its episome by reprogramming cells without transgene silencing.

Another important feature of reprogramming vectors is the ability to remove or silence transgene expression upon successful iPSC generation, as this results in iPSCs that more closely resemble true ESCs in their gene expression profiles (34, 35). As HVS episomal maintenance relies on the expression of the ORF73 protein alone (22–24), modified HVS-based vectors could be produced to regulate the expression of the ORF73 protein, allowing removal of the viral episome upon successful reprogramming. This would completely eradicate the exogenous expression of reprogramming transgenes and viral DNA upon iPSC generation, a trait that is preferable to inducible integrating vectors, where there is a potential for “leaky” repression of transgenes and vector DNA remains in reprogrammed cells. Taken together, these findings make HVS-based vectors a potential and attractive gene delivery vector for the generation of iPSCs and iPCs.

In this study, we assessed the potential of HVS-based vectors as a nonintegrating, episomally maintained system for the generation of iPCs from a Ewing's sarcoma family tumor (ESFT) cell line. ESFTs are the second most frequent malignant bone tumors in adolescents, with a peak incidence between the ages of 14 and 20 years. The prognosis for affected patients is poor, with survival rates of around 50% at 5 years or less than 25% should metastasis be present at the time of diagnosis (36). This high mortality rate and the potential cancer stem cell involvement in metastasis make ESFT iPCs of great interest and valuable tools to investigate ESFT development and provide a suitable platform for drug screening.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The A673 ESFT cell line human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and owl monkey kidney (OMK) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Lonza) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamate (Lonza), and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin. The ESFT cell lines TC32 and TTC466 were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with the same antibiotics and FCS. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The control iPSC line used in this study, ShiPS-FF5, was reprogrammed at the Centre for Stem Cell Biology, University of Sheffield, through lentiviral overexpression of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Lin28 in human foreskin fibroblasts. ShiPS-FF5 cells are karyotypically normal, have typical ESC morphology, and express pluripotency markers SSEA4, Tra1-81, Oct4, and Nanog. These iPSCs were grown under standard human ESC (hESC) culture conditions on mouse feeders or feeder free on Matrigel (BD) in mTeSR (Stemcell Technologies).

Virus vector construction.

Recombinant virus production was performed with the HVS-GFP-bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) as previously described (37). This contains a recombinant strain of HVS A11-S4 with a BAC cassette inserted into ORF15 (38). Initially, each iPSC cDNA was PCR amplified (the sequences of the oligonucleotides used are available on request) from lentiviral constructs containing cDNAs of Oct4, Lin28, and Nanog (Addgene). The resulting PCR products were cloned into pEGFP-c1 (Clontech), replacing the enhanced GFP (EGFP) coding region via AgeI/EcoRI restriction digestion. Each iPSC expression cassette was then amplified from piPSC-c1 and subsequently cloned into pShuttle Link-1 (38), via NotI and MluI restriction sites (the sequences of the oligonucleotides used are available on request). HVS-iPSC-BAC recombinant viruses were then generated by the subcloning of each iPSC expression cassette from pShuttle-iPSC constructs into HVS-GFP-BAC by I-PpoI restriction digestion as previously described (38, 39) to yield HVS-Oct4, HVS-Lin28, and HVS-Nanog.

Recombinant HVS-based vector production and analysis.

Recombinant infectious HVS was produced by the transfection of each HVS-iPSC DNA into permissive OMK cells. Transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in serum-free (SF) medium. Four micrograms of viral BAC DNA was transfected into one well of a six-well plate of confluent cells with 10 μl of the transfection agent according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 6 h of incubation, the SF medium was replaced with 5% medium. Viral growth was monitored by visualizing EGFP-positive plaques in the cell monolayer. Upon complete lysis, the supernatant was used in second-round infections of OMK cells to amplify virus. To quantify viral titers, plaque assays were performed as previously described (40).

To confirm the expression of the respective iPSC gene upon HVS infection, 1 × 106 293T cells were transduced with each HVS-iPSC recombinant virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were harvested, lysed, and resuspended in Laemmli loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 50 μg/ml bromophenol blue, 10 mM dithiothreitol) prior to separation by 10% SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was then performed with Oct4 (Santa Cruz)-, Nanog (Abcam)-, and Lin28 (Abcam)-specific antibodies. After being washed, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Dako) prior to the visualization of specific bands by enhanced chemiluminescence.

PFGE.

To analyze restriction digests of recombinant viral genomes, 1.2% agarose gels were made with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) grade agarose (Sigma) and 0.5× TBE buffer (0.0225 M Tris-borate, 0.001 M EDTA). A Bio-Rad PFGE tank was filled with 0.5× TBE that had been precooled to 15.5°C with a Bio-Rad model 100 minichiller unit and circulated with a variable-speed pump. The cooling unit and pump were turned off for gel loading. Midrange PFG Marker II (New England BioLabs) was used along with Lambda DNA HindIII Digest (New England BioLabs) to compare sizes of DNA fragments. The CHEF-DR II drive module was programmed under the following conditions: 6 V, 12.5 h, initial and final switch intervals of 2.0 and 16.0 s. Samples were allowed to run into the gel for approximately 20 min, after which the cooling unit and pump were switched on. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with 200 ml of 0.1 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma) in 0.5× TBE buffer.

Generation of A673 iPCs.

One day prior to infection, 2 × 104 A673 cells were seeded per six-well plate. Reprogramming was initiated by infecting cells with HVS-based vectors at an MOI of 0.5 per six-well dish in DMEM containing 5% FCS. If multiple viruses were used, a total MOI of 1.5 was maintained with HVS-GFP. Cell were washed 1 day postinfection (p.i.), and the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FCS. At day 4 p.i., cells were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA, plated onto 10-cm Primaria dishes, and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS and 100 μg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen). The medium was refreshed every 2 days until the emergence of colonies at day 19 p.i. Day 20 p.i. colonies were individually picked to 24-well dishes precoated in Matrigel ESC-qualified extracellular matrix (BD Biosciences) and cultured in medium consisting of 45% DMEM, 50% mTeSR, and 5% FCS to allow adjustment to SF culture conditions. At day 21 p.i., the medium was replaced with 100% mTeSR and colonies were maintained for a further 1 to 2 weeks until large enough to split. Colonies were split by treatment with collagenase IV (Stemcell Technologies) for 5 min, washing in mTeSR medium, and scoring with a pipette tip before pipetting to break them up. The control iPSC line, ShiPS-FF5, was grown in parallel on Matrigel and 100% mTeSR and passaged every 5 days with collagenase IV.

Analysis of HVS-based vector episomal persistence.

Circular episomes were recovered from cells grown in six-well dishes by the preparation of low-molecular-weight DNA as described previously (38). One microliter of the DNA was electroporated into Electromax Escherichia coli DH10B (Invitrogen) and plated on LB agar supplemented with 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of extracted DNA was also performed. Ten nanograms of DNA was added to 2× SensiMix SYBR green (Bioline) containing 5 μM forward and reverse oligonucleotides and analyzed on a Rotor-Gene Q 2-plex thermocycler (Qiagen) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation for 10 min at 95°C and then 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. All samples were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used are available upon request.

Alkaline phosphatase staining.

Colonies were analyzed for alkaline phosphatase activity by staining with Alkaline Phosphatase Staining Kit II (Stemgent) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunocytochemistry.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline. Nonspecific antibody binding was prevented by blocking cells in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 15 min. Cells were stained without prior permeabilization with an SSEA4-specific antibody from the hybridoma MC813-70 (41). Cells were then washed and stained with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) was used as a cell-permeating nuclear stain.

Real-time qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and DNase treated with an RNase-free DNase kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturers' protocols. cDNA was produced with 2.5 μg of RNA with 50 μM oligo(dT) primers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (New England BioLabs) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), 10 ng of cDNA was added to 2× SensiMix SYBR green (Bioline) containing 5 μM forward and reverse oligonucleotides and analyzed on a Rotor-Gene Q 2-plex thermocycler (Qiagen) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation for 10 min at 95°C and then 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s. All samples were normalized to GAPDH. The manufacturer's software was used to analyze results as previously described (42). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used are available upon request.

Differentiation assays.

iPSC and iPC colonies were split, seeded onto nonadherent six-well plates, and cultured in suspension cultures for 8 days in DMEM containing 10% FCS to form embryoid bodies (EBs). Subsequently, EBs were plated onto gelatin-coated six-well dishes and allowed to grow for 8 days before imaging and harvesting of the EBs in TRIzol. For neural differentiation, a adaptation of the protocol of Bain et al. (43) was used. Colonies were seeded onto nonadherent six-well plates and cultured in StemPro NSC SF medium (Invitrogen) for 2 days to form EBs. EBs were then transferred to gelatin-coated six-well dishes and cultured for a further 8 days before imaging and harvesting in TRIzol reagent.

RESULTS

HVS can efficiently infect ESFT cell lines.

A population of cancer stem cells have recently been identified within ESFTs (44). Taken together with the ability of HVS to efficiently infect multicellular spheroids formed by ESFT cells (28), ESFTs were chosen as an ideal proof-of-principle model to assess the potential of HVS-based vectors to produce iPCs.

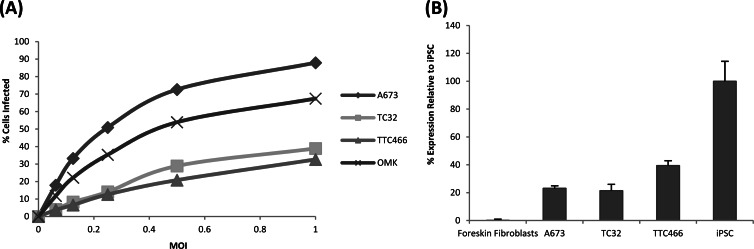

To initially determine the most appropriate ESFT cell line to use in reprogramming efforts, a range of ESFT cell lines were infected with various MOIs of HVS-GFP and the percentage of GFP-expressing cells was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis at 24 h p.i. The results demonstrate that the A673 ESFT cell line exhibited the highest infectivity rates, with 87% of the cell population becoming GFP positive upon transduction with HVS-GFP at an MOI of 1. This transduction rate was considerably higher than that of the other ESFT cell lines, TC32 (32%) and TTC466 (38%), and the permissive cell line OMK (70%) (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

Characterization of ESFT cell lines. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of HVS-GFP infection rates in ESFT cell lines at various MOIs at 24 h p.i. Infectivity is expressed as the percentage of the total number of counted cells that were GFP positive. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of endogenous Sox2 expression in ESFT cell lines. Expression is displayed as a percentage of the iPSC Sox2 mRNA level, which was taken to be 100%.

Recent findings have demonstrated that it is possible to reprogram NSCs to iPSCs upon exogenous Oct4 expression alone (4), as NSCs endogenously express Sox2 (45). This finding has important implications for reprogramming efforts, as it minimizes the number of vectors required that express exogenous factors. Interestingly, ESFT cells express certain neuronal markers and it has been suggested that they may originate from mesenchymal stem cells that have induced neuronal marker expression conferring a neural phenotype (46, 47). Therefore, prior to reprogramming, we assessed whether any ESFT cells expressed endogenous Sox2. Real-time qRT-PCR of whole-cell RNA extracted from each ESFT cell line was performed, and Sox2 mRNA levels were compared to those of control iPSCs. The results demonstrate that all three ESFT cell lines endogenously express Sox2, with A673 cells expressing 20% of the Sox2 levels observed in the control iPSCs (Fig. 1B). Therefore, combining the highest rates of infectivity and endogenous Sox2 expression observed in the A673 cell line, these cells were selected for iPC reprogramming efforts.

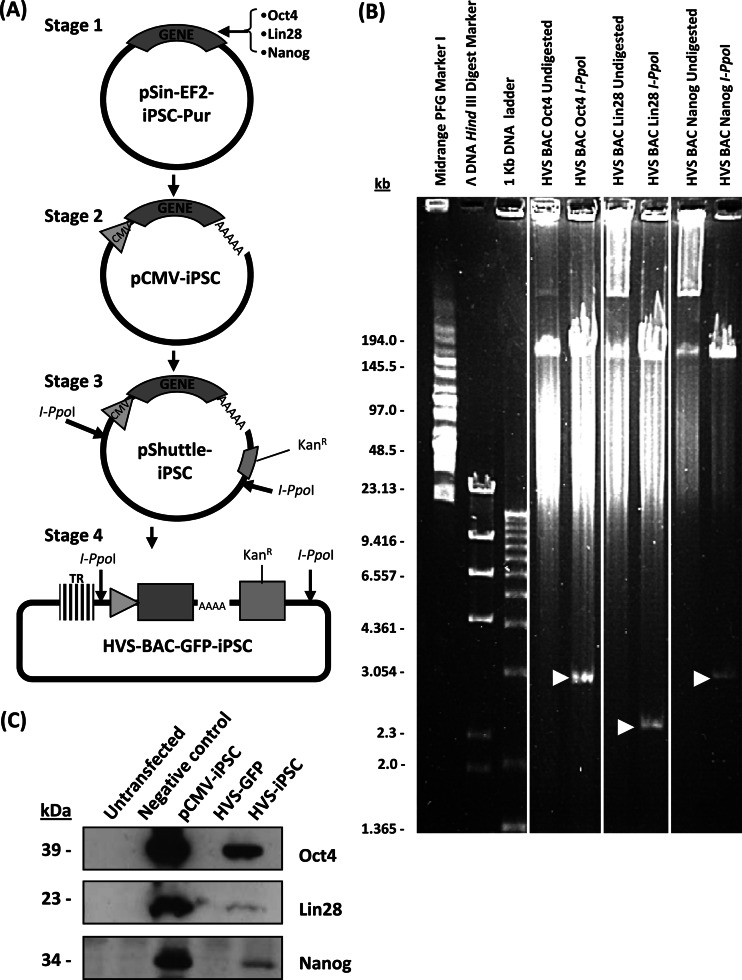

Production of HVS-based vectors expressing iPSC reprogramming genes.

The HVS-GFP-BAC allows heterologous gene expression cassettes to be easily inserted into HVS-based vectors in a nondisrupting, site-specific manner (37). Although NSCs have been shown to require only Oct4 expression for successful reprogramming, as they express endogenous Sox2, adult somatic cells require a combination of reprogramming factors, originally Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc (1), but Oct4, Sox2, Lin28, and Nanog are also commonly used because of the oncogenic nature of Klf4 and Myc (3). Therefore, as ESFTs endogenously express Sox2, the remaining iPSC reprogramming genes for Oct4, Nanog, and Lin28 were cloned into HVS-based vectors. Each gene was inserted downstream of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early (IE) promoter and cloned into the polylinker of pShuttle-Link1 (38), adjacent to a kanamycin selection marker and flanked by I-PpoI restriction sites. Each iPSC expression cassette was then excised from pShuttle-Link1 and cloned into the HVS-GFP-BAC via its unique I-PpoI site (Fig. 2A). Positive colonies were selected by kanamycin selection and further screened via restriction digestion with I-PpoI, which excises each iPSC expression cassette from the linearized 174-kb BAC plasmid. PFGE demonstrates the generation of recombinant HVS-BAC genomes containing Oct4, Nanog, and Lin28 expression constructs (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

Generation and characterization of HVS-iPSC-BAC recombinant viruses. (A) Schematic representation of the cloning procedure. iPSC genes were PCR amplified, and the resulting products were cloned into pEGFP-c1, replacing the EGFP coding region, to produce pCMV-iPSC constructs, thereby placing iPSC genes under the control of the CMV IE promoter. CMV-iPSC expression cassettes were PCR amplified and cloned into the pShuttle Link 1 vector prior to subcloning into predigested HVS-GFP-BAC at flanking I-PpoI restriction sites. (B) PFGE of HVS-iPSC-BAC recombinants. The presence of the iPSC expression cassettes was confirmed by I-PpoI restriction digestion (white arrows). (C) 293T cells were either transfected with pCMV-iPSC constructs or infected with each HVS-iPSC viral vector expressing Oct4, Lin28, or Nanog at an MOI of 1. After 24 h, the cell lysates were immunoblotted with Oct4-, Lin28-, and Nanog-specific antibodies. Negative controls included pEGFP-c1-transfected cells and HVS-GFP-infected cells. Expression of iPSC transgenes is confirmed by the presence of specific bands at 39, 23, and 34 kDa for Oct4, Lin28, and Nanog, respectively.

HVS constructs were then transfected into permissive OMK cells to produce recombinant virus as previously described (37). The HVS-BAC recombinants were then assessed for the ability to deliver and express each iPSC reprogramming factor. 293T cells were infected with each recombinant virus at an MOI of 1, and infected cells were harvested at 48 h p.i. Cell lysates were then analyzed by immunoblotting with Oct4-, Nanog-, and Lin28-specific antibodies (Fig. 2C). The results show the correct expression of each transgene, indicated by the presence of 39-, 23-, and 34-kDa protein species for Oct4, Lin28, and Nanog, respectively.

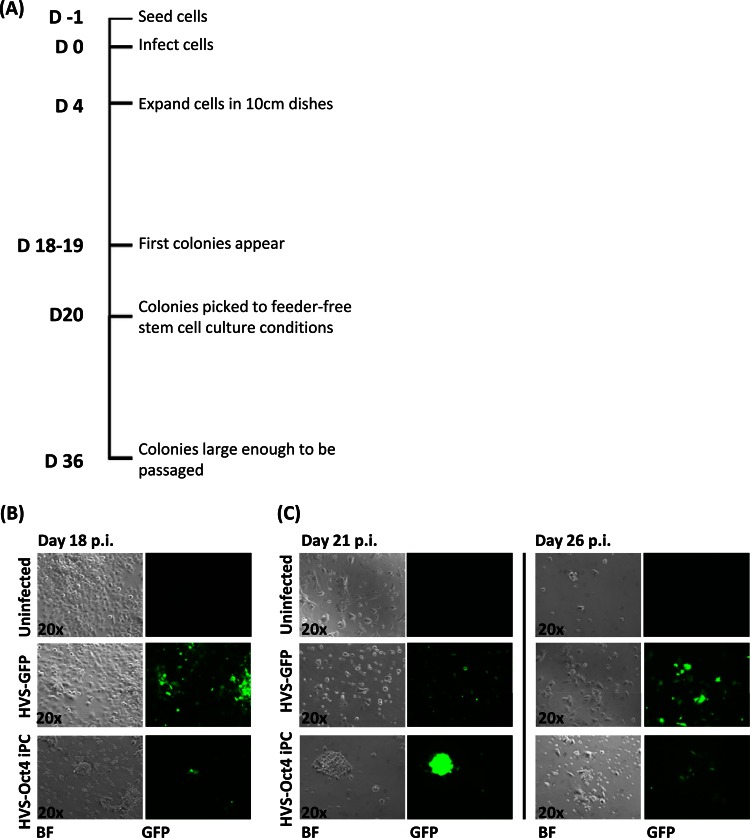

Transient reprogramming of A673 cells with only HVS-Oct4.

Previous studies have demonstrated that NSCs endogenously expressing Sox2 can be reprogrammed by exogenous Oct4 expression alone (4). Initial findings in this study demonstrated that ESFT cells also express endogenous Sox2. Therefore, initial reprogramming attempts were performed with A673 cells and HVS-Oct4, the methodology of which is summarized in Fig. 3A. Cells (1 × 106) were either mock infected or infected with control HVS-GFP or HVS-Oct4 at various MOIs of 0.06 to 1.0. This range of MOIs was used because an MOI of 1 showed a maximum infectivity rate of 80% (Fig. 1A). At 4 days p.i., the cells were transferred to 10-cm dishes for expansion and colony formation. At 19 days p.i., colonies possessing a tightly packed, spheroidal morphology were observed that were clearly distinct from the control A673 cells. In contrast, no colonies were formed by mock- or HVS-GFP-infected cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

A673 iPC reprogramming attempts by HVS-Oct4 transduction. (A) Schematic representation of the methodology used to generate iPCs. (B) iPC colonies appear at 18 days p.i. in A673 cells transduced with HVS-Oct4 at an MOI of 0.5 but are absent from mock- and HVS-GFP-infected control cells. The presence of the HVS-Oct4 episome within these cells is demonstrated by GFP expression. (C) iPCs were picked at day 20 p.i. and cultured under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. Colonies were still viable under these culture conditions 1 day after picking but were incapable of surviving prolonged culture. Examples showing that the colonies had deformed at day 26 p.i. are included. Bright-field (BF) and fluorescence microscopy (GFP) images are shown.

These colonies were then assessed for the ability to grow under conditions allowing the feeder cell-independent growth of stem cells. At day 20 p.i., the colonies were transferred to plates precoated in hESC-qualified Matrigel and cultured in medium consisting of 45% DMEM, 50% mTeSR, and 5% FCS to allow the cells to adjust to the feeder-free stem cell mTeSR culture conditions. The following day, the medium was replaced with feeder-free stem cell culture conditions (100% mTeSR). The results showed that the colonies were still viable at day 21 p.i., retaining their densely packed spheroidal morphology. However, further culturing under stem cell culture conditions caused the colonies to deform, with cells growing out from the colony and extensive cell death occurring, as shown at day 26 p.i. (Fig. 3C). The uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected control cells failed to grow under these stem cell culture conditions, which clearly indicates a transition to another more stem cell-like cell type. However, the limited survival time under these conditions suggests that HVS-based delivery of Oct4 alone is insufficient to maintain these phenotypically reprogrammed A673 cells.

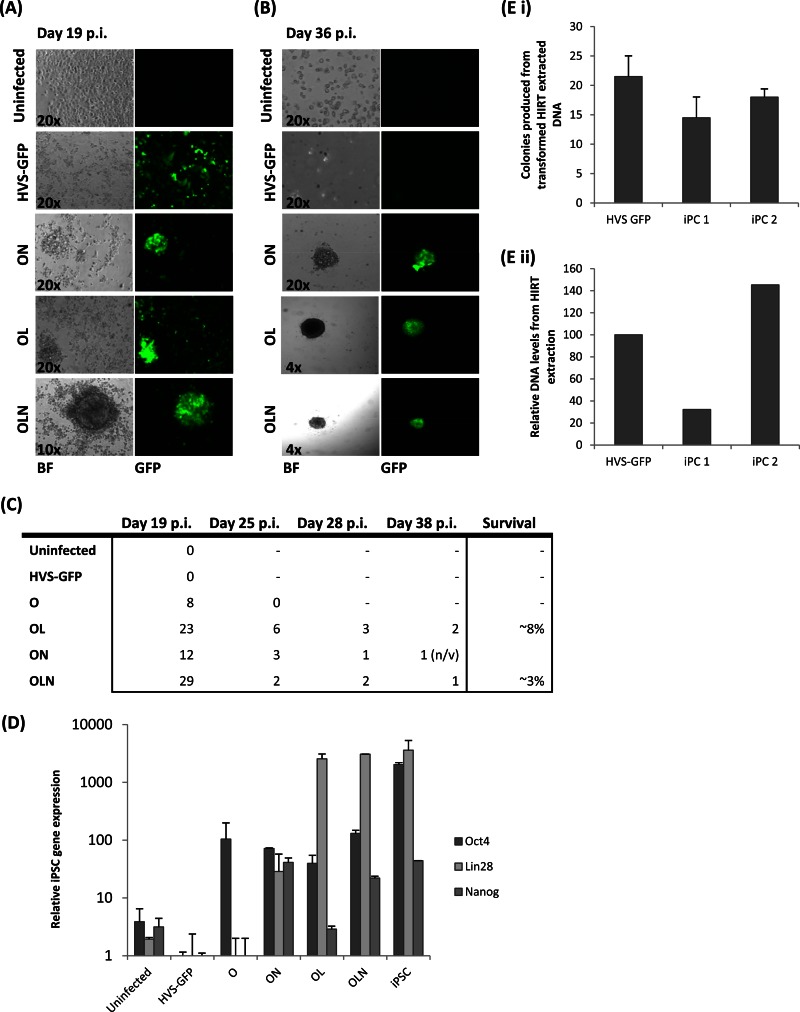

Reprogramming of A673 cells with HVS-based vectors expressing Oct4, Nanog, and Lin28.

The initial formation of stem cell-like colonies but subsequent deformation could indicate that HVS-Oct4 alone is not sufficient to reprogram A673 cells and that additional iPSC reprogramming factors are required. Therefore, a second reprogramming attempt was undertaken with the additional HVS vectors expressing Nanog and Lin28 reprogramming factors. A673 cells were infected with HVS-Oct4 in combination with HVS-Lin28 (OL), HVS-Nanog (ON), or both viruses (OLN). Cells were transduced and cultured as described above, and colonies possessing the same tightly packed spheroidal appearance were once again observed at 18 to 19 days p.i. (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Generation of A673 iPCs by combined infection of HVS-iPSC vectors. To improve reprogramming efficiency, the following combinations of HVS-iPSC vectors were used to infect A673 cells: ON, HVS-Oct4 and HVS-Nanog; OL, HVS-Oct4 and HVS-Lin28; OLN, HVS-Oct4, HVS-Lin28, and HVS-Nanog. Each virus was used at an MOI of 0.5. (A) iPC colonies formed at day 19 p.i. in cells infected with combinations of the HVS-iPSC vectors but were absent from mock- and HVS-GFP-infected controls. The presence of HVS-iPSC episomes within the iPCs was demonstrated by GFP expression. Bright-field (BF) and fluorescence microscopy (GFP) images are shown. (B) At day 36 p.i., surviving colonies were capable of expansion and prolonged growth under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. Altered magnifications were used as colonies expanded. (C) Table depicting colony survival rates upon the addition of different virus infection combinations. (D) qRT-PCR to indicate the amounts of total iPSC gene expression in cells infected with the different combinations of HVS-based vectors at day 21 p.i. (E) HVS episomal DNA was isolated from control HVS-GFP-infected A673 cells and iPC colonies 1 and 2. Episomal DNA was quantified by transformation and selection on chloramphenicol plates (i) and qPCR (ii).

As previously, colonies were then cultured under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. After prolonged culture under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions (36 days p.i.), some colonies from each virus combination condition deformed as previously observed (data not shown). However, the majority of the colonies were still viable and expanded for further analysis. A selection of these established colonies are shown in Fig. 4B. Colonies derived from OLN and OL infections produced stable colonies possessing densely packed morphologies and phase-bright characteristics indicative of stem cell-like colonies; in contrast, colonies derived from ON infections often appeared much smaller and possessed poorly defined edges. Moreover, long-term expansion of these ON colonies was unsuccessful. Therefore, initial A673 cell reprogramming efforts suggest that exogenous HVS-based delivery of OLN or OL can reproducibly produce stem cell-like colonies that are able to grow under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. The survival rates of 3 to 8% shown in Fig. 4C are similar to those found in previous iPC reprogramming efforts (6).

To further analyze the variation in the survival rates of the colonies produced by different combinations of viruses, levels of total iPSC gene expression were analyzed by qRT-PCR. RNA was extracted from cells infected with each virus combination at day 21. This day was chosen because all of the cells were still viable and colonies were observed at this time point (Fig. 4D). The results show that in all cases, levels of exogenous iPC gene expression were observed and, for example, in the case of OLN infection, the levels were similar to the expression levels found in iPSCs. Therefore, survival rates are unlikely to be due to a lack of exogenous iPSC gene expression from the HVS-based vector. Interestingly, the colonies that displayed the best viability possessed Lin28 expression levels similar to those observed in the control iPSCs.

To confirm that the HVS episome is maintained during A673 reprogramming efforts, episomal rescue assays were performed. Circular episomes were recovered by the preparation of low-molecular-weight DNA from infected HVS-GFP control cells and two iPC colonies (both derived from OL infection). Moreover, qPCR was also performed to verify the relative abundance of HVS episomal DNA. The results show that episomes were recovered from controls and both iPC colonies, demonstrating the persistence of the HVS episome during reprogramming protocols (Fig. 4E).

A673 iPC colonies stain positively for alkaline phosphatase and SSEA4.

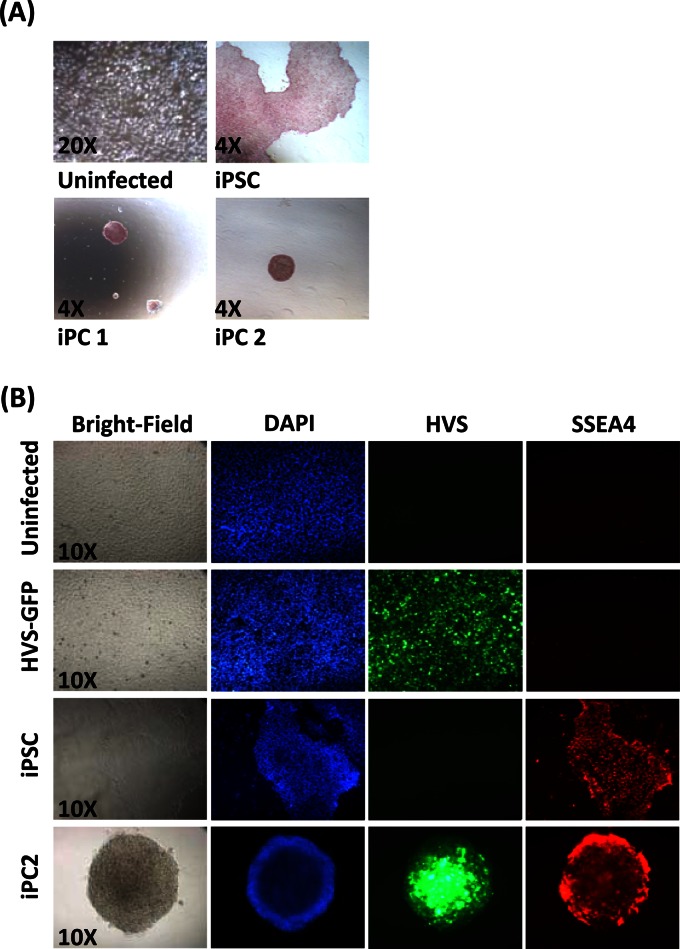

ESCs express elevated levels of alkaline phosphatase on their surface (48). Therefore, the putative A673 iPC colonies generated were screened for the ESC-like characteristic of alkaline phosphatase activity. We chose iPC colonies 1 and 2, derived from OL infections, because they had the best survival rates. The iPSC line ShiPS-FF5 and uninfected A673 cells served as positive and negative controls, respectively. In contrast to the A673 cell negative control, iPSCs and putative A673 iPC colonies both stained positive for alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

Characterization of putative A673 iPC colonies. (A) A673 iPC colonies stain positive for alkaline phosphatase activity (both iPC colonies 1 and 2, which were derived from OL infections). Uninfected A673 cells and iPSCs served as negative and positive controls, respectively. (B) A673 iPC colonies express the cell surface marker SSEA4 (red). Hoechst 33342 was used as a nuclear stain (blue), and the presence of HVS episomes is demonstrated by GFP. Uninfected or HVS-GFP-infected A673 cells and iPSCs served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

A further indicator of ESC-like characteristics is the upregulation of the cell surface protein SSEA4 (48). Therefore, immunofluorescence analysis of the A673 iPC colonies was also performed with an SSEA4-specific antibody. The iPSC line ShiPS-FF5 was used as a positive control, and uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected A673 cells served as negative controls. The results show SSEA4 expression in the putative A673 iPC colonies and positive-control iPSCs (Fig. 5B). In contrast, SSEA4 staining was not observed in the uninfected and HVS-GFP-transduced control cells. These data, together with the observed morphology change, provide the first preliminary indication of the occurrence of HVS-based reprogramming of the putative A673 iPC colonies into a stem cell-like state.

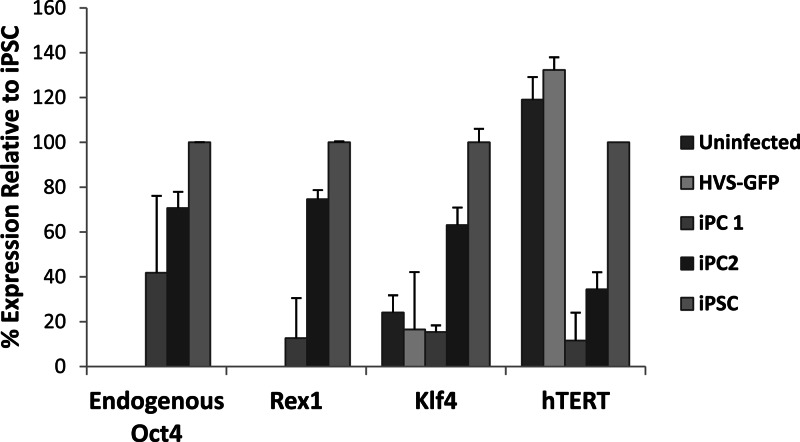

A673 iPC colonies demonstrate elevated levels of pluripotency marker genes.

Various genes are known to be upregulated in pluripotent stem cells to maintain their proliferation and self-renewal. Therefore, induced endogenous expression of these genes is a good indication of iPSC generation (1, 48). Therefore, to test if HVS-based iPC reprogramming of A673 cells had been achieved, the expression of a number of pluripotency marker genes was analyzed in the putative A673 iPC colonies generated. RNA was extracted from two putative iPC colonies, negative-control uninfected A673 cells and HVS-GFP A673 cells and positive-control iPSCs. qRT-PCR was then used to assess the expression of the pluripotency marker genes for Oct4, Rex1, Klf4, and hTERT within these cells. Importantly, to ensure that only endogenous Oct4 levels were measured, the 5′ primer used for Oct4 transcript detection was designed within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the Oct4 mRNA, thereby preventing any amplification from exogenous Oct4. The results demonstrate increased levels of endogenous Oct4, Rex1, and Klf4 mRNAs in the two A673 iPC colonies and positive-control iPSCs, compared to those in uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected A673 control cells (Fig. 6). Interestingly, however, variations in marker gene expression do differ between A673 iPC colonies. Moreover, hTERT levels in uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected control cells were similar to those observed in the reference standard iPSCs, with reduced mRNA levels seen in the iPC colonies. These data demonstrate the induction of some endogenous pluripotency marker genes in the HVS-generated putative A673 iPCs.

Fig 6.

qRT-PCR analysis of endogenous ESC marker gene expression in A673 iPCs. Oct4, Rex1, Klf4, and hTERT mRNA levels were assessed in uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected A673 cells, A673 iPC colonies 1 and 2, and iPSCs. The expression of each respective gene is shown as a percentage of the mRNA level in the iPSCs, which represents 100%. To ensure no amplification of viral transgene Oct4 mRNA, primers were designed within the 5′ UTR of Oct4.

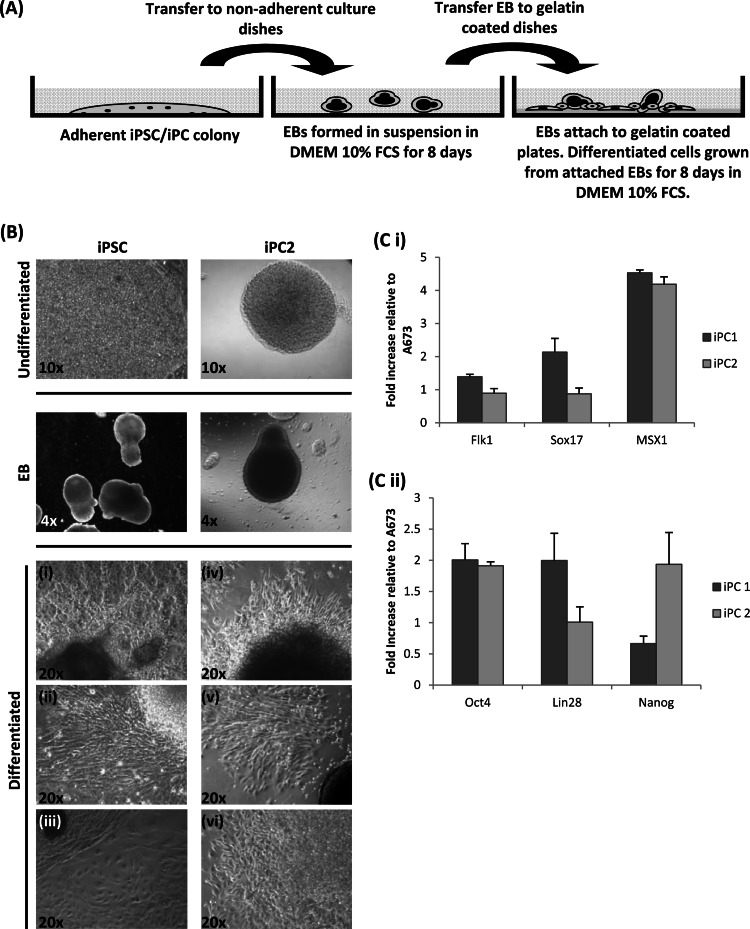

Nonspecific differentiation studies of A673 iPC colonies.

One of the defining features of CSCs is the ability to seed new tumors by differentiating into various types of tumor stromal cells. However, little is known about the exogenous signals involved in this differentiation process because of the difficulties in isolating CSCs. Therefore, iPCs could potentially provide an abundant source of cells, thereby allowing the determination of signaling pathways involved in the various types of differentiation in both in vitro and in vivo models. Therefore, to assess the potential of HVS-generated putative A673 iPC colonies as models of ESFT development and progression and to further ascertain the extent of their stem cell-like properties, differentiation trials were performed.

First, the putative A673 iPC colonies were nonspecifically differentiated (Fig. 7A). To this end, EBs were first produced by culturing the putative A673 iPC colonies in DMEM containing 10% FCS. Figure 7B demonstrates that EBs were efficiently formed. After 8 days in suspension culture, the EBs were transferred onto gelatin coated dishes and differentiated cells were allowed to grow out from the central colony mass for a further 8 days. Cells possessing various morphologies, predominantly fibroblast like (Fig. 7B, top and middle), were observed upon both iPSC and A673 iPC nonspecific differentiation. In addition, morphologies closely resembling that of parental A673 cells were also observed in differentiated A673 iPCs (Fig. 7B, bottom).

Fig 7.

Nonspecific differentiation assay. (A) Schematic representation of the nonspecific differentiation methodology used. (B) A673 iPCs (iPC colony 2 was derived from an OL infection) and iPSC positive-control cells were differentiated by the initial formation of EBs in DMEM–10% FCS. EBs were subsequently grown on gelatin coated plates, and differentiated cells were allowed to grow from the attached EBs. Examples of the morphologies observed are shown in differentiated cells from iPSCs (i to iii) and A673 iPCs (iv to vi). (C i) qRT-PCR analysis for mesoderm (Flk1), endoderm (Sox17), and ectoderm (MSX1) marker gene expression. Fold increases in mRNA levels of A673 cells and two independent differentiated putative A673 iPC colonies are compared. (C ii) qRT-PCR analysis of iPSC gene expression in EBs compared to that in A673 cells.

Upon ESC differentiation, genes associated with pluripotency are rapidly downregulated and germ line-specific genes are activated (49). Therefore, to determine the extent of putative A673 iPC colony differentiation, RNA was extracted from control uninfected and HVS-GFP-infected A673 cells and two differentiated A673 iPC colonies and qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression levels of lineage-specific markers of the three germ layers, i.e., ectodermal marker MSX1, endodermal marker Sox17, and mesodermal marker Flk1. Undifferentiated and differentiated iPSCs (grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS) also served as a positive control and showed the upregulation of all three lineage markers upon differentiation (data not shown). In contrast, differentiation of the putative A673 iPCs resulted in elevated levels of only the ectodermal marker MSX1 in both colonies (Fig. 7Ci). To further investigate whether this apparent bias in differentiation potential was due to residual iPSC gene expression caused by persistence of the HVS-based vector, qRT-PCR was performed to examine iPSC gene expression in resulting EBs. The data show that although there was a small amount of elevated iPSC gene expression (Fig. 7Cii), this was much lower than the levels in iPCs (Fig. 4D). This suggests that A673 cells may have a preference for the ectodermal lineage. Moreover, it may suggest that partial reprogramming has occurred, making these putative iPCs multipotent rather than pluripotent in nature, and that they may be more appropriately termed A673-induced multipotent cancer stem cells (iMCs).

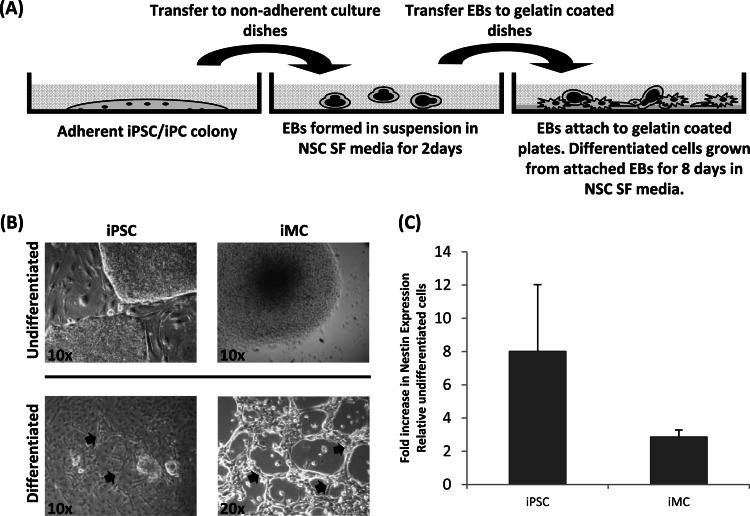

Neural lineage-directed differentiation of A673 iMC colonies.

A further test of the multipotent nature of A673 iMCs is to assess their directed differentiation potential toward a specific lineage. Therefore, as ESFTs express certain neuronal markers, the A673 iMC colonies were cultured under conditions used to differentiate ESCs down the neural lineage (50). A673 iMC colonies were grown as described above to form EBs and then transferred to gelatin-precoated dishes and cultured for a further 8 days in NSC medium (Fig. 8A) to test if some cells develop to an NSC stage. As a positive control, differentiation of iPSCs was also performed under similar conditions. Control iPSCs developed neuroprogenitor-like morphologies, with some cells continuing to differentiate and forming neuronal networks (Fig. 8B, arrows). Differentiation of the HVS-generated putative A673 iMCs appears to result in similar morphologies, albeit to a lesser extent, showing some ability to form neural-crest-like morphologies and neuronal networks (Fig. 8B, arrows). This suggests that HVS-generated putative A673 iMCs are capable of the initial stages of neural differentiation.

Fig 8.

Neuronal differentiation assay. (A) Schematic representation of the neuronal differentiation methodology used. (B) A673 iPCs and iPSC positive-control cells were differentiated by the initial formation of EBs in NSC SF medium. EBs were subsequently grown on gelatin-coated plates, and differentiated cells were allowed to grow from the attached EBs. (B) Differentiated cells in iPSCs and A673 iPCs form neural networks (arrows). (C) Levels of mRNA for Nestin, a marker of neuroprogenitor cells, were analyzed in differentiated cells. Fold increases in mRNA levels in iPSCs (left) and A673 cells (right) over those in terminally differentiated cells are shown.

To further investigate initial differentiation along the neuronal lineage, RNA was extracted from control uninfected, HVS-GFP-infected, and differentiated A673 iMCs and qRT-PCR was performed to assess the expression of Nestin, a neural progenitor cell marker (Fig. 8C). Undifferentiated and differentiated iPSCs (cultured in NSC medium) also served has a positive control. As expected, Nestin mRNA levels were increased upon iPSC neuronal specific differentiation. Similarly, an upregulation of the NSC marker Nestin was observed upon putative A673 iMC differentiation, suggesting that some degree of neural differentiation can occur in the putative A673 iMC colonies (Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

The vectors most widely used for iPSC production are retroviruses. Retroviral vectors have the advantage of providing prolonged expression of the reprogramming factors essential for efficient reprogramming. However, they can preferentially integrate into highly expressed regions of the genome, disrupting normal gene function by causing overexpression of genes related to proliferation or, alternatively, silencing regulatory genes (7). Therefore, to circumvent these issues, with particular regard to the production of iPCs, alternative vectors are required. HVS-based vectors possess a number of features that make them attractive gene delivery vectors for iPC generation.

HVS has a broad cell tropism, having the ability to infect a wide range of primary and cancerous tissues (16, 17). Moreover, upon infection, the viral genome persists as high-copy-number, circular, nonintegrated episomes that segregate to progeny cells upon division, a process that is mediated by the ORF73 episomal maintenance protein (22–25). This not only reduces the risk of insertional mutagenesis and gene silencing by epigenetic mechanisms but also allows the HVS-based vector to stably transduce nondividing and dividing cell populations and provide sustained heterologous gene expression. Therefore, it offers the characteristics of an artificial chromosome combined with a highly efficient delivery system. Further developments include the generation of an HVS amplicon system to both improve biosafety and increase transgene capacity (51), thus enabling the generation of a single gene delivery vector encompassing all of the factors required for efficient reprogramming. In this paper, we show the potential of HVS-based vectors for the reprogramming of cancer cells; in the future, a further development would be to use their large packaging capability to produce a single vector expressing the appropriate reprogramming factors. However, optimal stoichiometry of gene expression must be examined carefully to ensure the best reprogramming ratios. Previous attempts to generate single vectors containing multiple reprogramming factors have used polycistronic constructs that contain each reprogramming gene separated by self-cleaving 2A peptides from the foot-and-mouth disease virus (52, 53). Although these polycistronic constructs improve transduction or transfection efficiency, the reprogramming efficiency of these methods remains poor, maybe as a result of incomplete translation and poor cleavage. Therefore, an advantage of the HVS packaging capability would be to incorporate each gene under the control of its own promoter, circumventing the issues arising from a polycistronic construct.

The potential of episomally maintained gene delivery methods has recently been demonstrated for iPSC generation, with a plasmid vector containing a polycistronic construct expressing reprogramming factors combined with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) episomal maintenance elements EBNA1 and OriP (54). Although this episome-based reprogramming method had poor efficiency because of transient transfection, reprogramming efficiency was enhanced by combining the episomal vector with basic fibroblast growth factor and leukemia inhibitor factor, in addition to small-molecule inhibitors of MEK, glycogen synthase kinase 3β, and transforming growth factor β (55). Therefore, in future applications, the efficiency of the HVS-based episomal reprogramming method may also be improved by reprogramming cells under these culture conditions.

Removal of reprogramming transgenes upon iPSC generation produces cells that more closely resemble true ESCs in their gene expression profiles (34, 35). Therefore, exogenous reprogramming factor expression should be regulated upon iPSC generation. Inducible expression systems have previously been incorporated into HVS-based vectors (32) and could provide sufficient control of reprogramming factor expression. However, although inducible systems regulate transgene expression, the exogenous vector remains in the reprogrammed cells, necessitating the use of Cre-LoxP excisable retroviruses and PiggyBac transposons (8, 9, 34, 56). However, these systems both require stringent screening of the resulting iPSCs to ensure that all of the exogenous DNA is removed. Once again, episomally maintained vectors have an advantage in this regard, as the episome could easily be removed upon reprogramming. For example, the EBV-based episomal reprogramming system was removed through repeated cellular divisions in the absence of a selective antibiotic (54). Alternatively, as HVS episomal persistence is reliant on a single virus-encoded protein, ORF73, it would be feasible to efficiently remove the viral episome by regulation of ORF73 expression. This could be achieved in a number of ways, including small interfering RNA-mediated depletion of the ORF73 protein, generation of a tetracycline-inducible ORF73 HVS vector, or creation of an HVS-based vector containing FLP recombination sites flanking the ORF73 gene, thereby creating an excisable ORF73 cassette. Therefore, upon disruption of ORF73 expression, viral episomes would be removed from reprogrammed cells by repeated cellular divisions in the absence of selection. A similar self-deleting, nonintegrating system based upon Sendai virus has recently been developed. Temperature-sensitive mutations enable removal of the vector at a nonpermissive temperature (14). This system is capable of efficient reprogramming, with subsequent removal of viral RNA genomes upon cell culturing at 38°C. However, genetic manipulation of this system is a complex and time-consuming process requiring a cDNA intermediate to be formed from the Sendai virus single-stranded genome. The generation of the HVS-BAC system enables fast and simple genetic manipulation of the HVS genome, thereby facilitating the production of HVS-based vectors. Furthermore, the capacity for transgenes is limited within the Sendai virus system, whereas HVS-based vectors can accept up to 50 kb of exogenous DNA, enabling whole genomic loci to be cloned. This could therefore provide more physiologically relevant expression of the desired transgenes.

Herein we show that although ESFT cell lines express endogenous Sox2, infection with HVS-Oct4 alone was insufficient to generate any putative A673 iPC colonies capable of thriving under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. This efficiency of reprogramming was improved by transducing the cells with HVS-Oct4 in conjunction with HVS-Lin28 or a combination of all three HVS-iPSC vectors. This resulted in a greater number of putative A673 iPC colonies, the majority of which were stable upon prolonged culture under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions. Analysis of these colonies by screening for alkaline phosphatase activity, qRT-PCR analysis of pluripotent marker genes, and staining for SSEA4 antigen expression demonstrated that these cells exhibited some hallmarks of ESCs. However, we believe that these putative A673 iPC colonies are probably in a state of incomplete or partial reprogramming because of the reduced levels of pluripotent marker gene expression compared to that in control iPSCs. An additional factor may be the lower levels of Sox2 expression observed in A673 cells than in iPSCs. In the future, it may be of interest to examine reprogramming rates in cell lines with increased levels of Sox2 expression.

Further evidence of possible incomplete reprogramming is highlighted in differentiation trials. The nonspecific and targeted differentiation results showed that the putative A673 iPCs possess some capacity for differentiation. However, pluripotency was not observed; rather, there was a preference for differentiation along the ectodermal lineage, as evidenced by MSX1 and Nestin upregulation. This suggests that the putative A673 iPCs are more multipotent in nature and that perhaps these colonies would be more accurately described as iMCs. One possible explanation for the putative A673 iPCs retaining the ability to differentiate toward the ectoderm lineage could be the presence of the EWS-FLI1 fusion protein. This protein has been demonstrated to upregulate the expression of various genes involved in neural development, including those for neuronal pentraxin receptor SMA5 and presenilin (46). Another possible factor that may reduce the capacity of putative A673-iMCs for differentiation is the residual transgene expression from the HVS episomes that persist in these cells. These genes are key regulators of pluripotency and repress the differentiation of stem cells. Therefore, residual expression of these genes within A673-iMCs would counteract their differentiation, although experiments suggest that this may not be the case, as Fig. 7Cii demonstrates very low levels of iPSC gene expression in EBs. It is possible, therefore, that upon differentiation, the transgene expression from HVS-based vectors is silenced. As described previously, future development of the HVS-iPSC vectors would include the implementation of a system to remove the HVS episomal maintenance element, thereby allowing the removal of any transgenes and exogenous vector DNA from reprogrammed cells. This would potentially produce iPSCs and iPCs that possess the same capacity for differentiation as true pluripotent stem cells.

Incomplete reprogramming has been reported previously in attempts to generate iPCs. Specifically, generation of iPCs from melanoma, leukemia, and lymphoma cells by somatic-cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) with enucleated oocytes has been attempted but complete reprogramming by SCNT was achieved only with melanoma cancer cells (57). Few recent studies have shown fully reprogrammed iPCs from cancer cells by using retroviral expression of the reprogramming factors (5, 6). Therefore, the limited number of successful reprogramming studies indicate an as-yet-unknown roadblock in the reprogramming of cancer cells. This is particularly surprising given the strong links between cancer and pluripotency that have been discussed previously (58, 59). Alternatively, it may be more likely that a variety of abnormalities found in cancer cells are not compatible with a pluripotent stem cell state or inhibit complete reprogramming itself. Therefore, future work to investigate the true potential of HVS-based vectors for iPC generation would involve reprogramming of the various stromal cells found within primary tumor samples. Moreover, in addition to highlighting which cells are most amenable to reprogramming, this would also provide insights into which cells are theoretically capable of dedifferentiating into fully reprogrammed iPCs or partially reprogrammed multipotent populations as described herein.

In summary, we detail the production of HVS-based vectors as a nonintegrating, episomally maintained reprogramming system capable of delivering the iPSC transgenes for Oct4, Nanog, and Lin28. These vectors are capable of inducing reprogramming, albeit incomplete, in the ESFT cell line A673. Resulting putative A673 iPC colonies could be cultured for prolonged periods under feeder-free stem cell culture conditions and exhibited a number of pluripotency characteristics. Moreover, they are able to undergo differentiation toward the ectodermal linage, suggesting that they are multipotent in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sue Burchill and Andrea Berry, University of Leeds, for providing reagents and useful advice on ESFT cell lines and Gareth Howell, Faculty of Biological Sciences Bioimaging, Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility.

This research was funded by a BBSRC DTG studentship. Control iPSC line ShiPS-FF5 was generated and characterized with MRC funding from Peter W. Andrews (Centre for Stem Cell Biology, University of Sheffield).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. 2006. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grskovic M, Javaherian A, Strulovici B, Daley GQ. 2011. Induced pluripotent stem cells—opportunities for disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10:915–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. 2007. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318:1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim JB, Greber B, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Meyer J, Park KI, Zaehres H, Scholer HR. 2009. Direct reprogramming of human neural stem cells by OCT4. Nature 461:649–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun C, Liu YK. 2011. Induced pluripotent cancer cells: progress and application. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 137:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagai K, Hoshino H, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. 2010. Defined factors induce reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:40–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daniel R, Smith JA. 2008. Integration site selection by retroviral vectors: molecular mechanism and clinical consequences. Hum. Gene Ther. 19:557–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A, Mileikovsky M, Mohseni P, Woltjen K. 2009. Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature 458:771–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hamalainen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu PT, Gertsenstein M, Kaji K, Sung HK, Nagy A. 2009. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 458:766–U106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, Weir G, Hochedlinger K. 2008. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science 322:945–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hong HJ, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. 2008. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science 322:949–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R, Kim KS. 2009. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell 4:472–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, Daley GQ, Brack AS, Collins JJ, Cowan C, Schlaeger TM, Rossi DJ. 2010. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 7:618–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, Tabata T, Saeki K, Shikamura M, Takada N, Inoue M, Hasegawa M, Kawamata S, Nishikawa S. 2011. Efficient generation of transgene-free human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature-sensitive Sendai virus vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14234–14239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falk LA, Wolfe LG, Deinhardt F. 1972. Isolation of herpesvirus saimiri from blood of squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 48:1499–1505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Griffiths RA, Boyne JR, Whitehouse A. 2006. Herpesvirus saimiri-based gene delivery vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 6:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Calderwood MA, White RE, Whitehouse A. 2004. Development of herpesvirus-based episomally maintained gene delivery vectors. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4:493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whitehouse A. 2003. Herpesvirus saimiri: a potential gene delivery vector (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 11:139–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simmer B, Alt M, Buckreus I, Berthold S, Fleckenstein B, Platzer E, Grassmann R. 1991. Persistence of selectable herpesvirus saimiri in various human haematopoietic and epithelial cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1953–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grassmann R, Fleckenstein B. 1989. Selectable recombinant herpesvirus saimiri is capable of persisting in a human T-cell line. J. Virol. 63:1818–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stevenson AJ, Clarke D, Meredith DM, Kinsey SE, Whitehouse A, Bonifer C. 2000. Herpesvirus saimiri-based gene delivery vectors maintain heterologous expression throughout mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation in vitro. Gene Ther. 7:464–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calderwood M, White RE, Griffiths RA, Whitehouse A. 2005. Open reading frame 73 is required for herpesvirus saimiri A11-S4 episomal persistence. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2703–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calderwood MA, Hall KT, Matthews DA, Whitehouse A. 2004. The herpesvirus saimiri ORF73 gene product interacts with host-cell mitotic chromosomes and self-associates via its C terminus. J. Gen. Virol. 85:147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Griffiths R, Whitehouse A. 2007. Herpesvirus saimiri episomal persistence is maintained via interaction between open reading frame 73 and the cellular chromosome-associated protein MeCP2. J. Virol. 81:4021–4032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collins CM, Medveczky MM, Lund T, Medveczky PG. 2002. The terminal repeats and latency-associated nuclear antigen of herpesvirus saimiri are essential for episomal persistence of the viral genome. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2269–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith PG, Burchill SA, Brooke D, Coletta PL, Whitehouse A. 2005. Efficient infection and persistence of a herpesvirus saimiri-based gene delivery vector into human tumor xenografts and multicellular spheroid cultures. Cancer Gene Ther. 12:248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith PG, Coletta PL, Markham AF, Whitehouse A. 2001. In vivo episomal maintenance of a herpesvirus saimiri-based gene delivery vector. Gene Ther. 8:1762–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith PG, Oakley F, Fernandez M, Mann DA, Lemoine NR, Whitehouse A. 2005. Herpesvirus saimiri-based vector biodistribution using noninvasive optical imaging. Gene Ther. 12:1465–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hiller C, Tamguney G, Stolte N, Matz-Rensing K, Lorenzen D, Hor S, Thurau M, Wittmann S, Slavin S, Fickenscher H. 2000. Herpesvirus saimiri pathogenicity enhanced by thymidine kinase of herpes simplex virus. Virology 278:445–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hiller C, Wittmann S, Slavin S, Fickenscher H. 2000. Functional long-term thymidine kinase suicide gene expression in human T cells using a herpesvirus saimiri vector. Gene Ther. 7:664–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Knappe A, Feldmann G, Dittmer U, Meinl E, Nisslein T, Wittmann S, Matz-Rensing K, Kirchner T, Bodemer W, Fickenscher H. 2000. Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed macaque T cells are tolerated and do not cause lymphoma after autologous reinfusion. Blood 95:3256–3261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wieser C, Stumpf D, Grillhosl C, Lengenfelder D, Gay S, Fleckenstein B, Ensser A. 2005. Regulated and constitutive expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines by nontransforming herpesvirus saimiri vectors. Gene Ther. 12:395–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doody GM, Leek JP, Bali AK, Ensser A, Markham AF, de Wynter EA. 2005. Marker gene transfer into human haemopoietic cells using a herpesvirus saimiri-based vector. Gene Ther. 12:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, Gao Q, Bell GW, Cook EG, Hargus G, Blak A, Cooper O, Mitalipova M, Isacson O, Jaenisch R. 2009. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell 136:964–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sommer CA, Sommer AG, Longmire TA, Christodoulou C, Thomas DD, Gostissa M, Alt FW, Murphy GJ, Kotton DN, Mostoslavsky G. 2010. Excision of reprogramming transgenes improves the differentiation potential of iPSCs generated with a single excisable vector. Stem Cells 28:64–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burchill SA. 2008. Molecular abnormalities in Ewing's sarcoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 8:1675–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Macnab SA, Turrell SJ, Carr IM, Markham AF, Coletta PL, Whitehouse A. 2011. Herpesvirus saimiri-mediated delivery of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumour suppressor gene reduces proliferation of colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 39:1173–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. White RE, Calderwood MA, Whitehouse A. 2003. Generation and precise modification of a herpesvirus saimiri bacterial artificial chromosome demonstrates that the terminal repeats are required for both virus production and episomal persistence. J. Gen. Virol. 84:3393–3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hong Y, Macnab S, Lambert LA, Turner AJ, Whitehouse A, Usmani BA. 2011. Herpesvirus saimiri-based endothelin-converting enzyme-1 shRNA expression decreases prostate cancer cell invasion and migration. Int. J. Cancer 129:586–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turrell SJ, Macnab SA, Rose A, Melcher AA, Whitehouse A. 2012. A herpesvirus saimiri-based vector expressing TRAIL induces cell death in human carcinoma cell lines and multicellular spheroid cultures. Int. J. Oncol. 40:2081–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kannagi R, Cochran NA, Ishigami F, Hakomori S, Andrews PW, Knowles BB, Solter D. 1983. Stage-specific embryonic antigens (SSEA-3 and -4) are epitopes of a unique globo-series ganglioside isolated from human teratocarcinoma cells. EMBO J. 2:2355–2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jackson BR, Boyne JR, Noerenberg M, Taylor A, Hautbergue GM, Walsh MJ, Wheat R, Blackbourn DJ, Wilson SA, Whitehouse A. 2011. An interaction between KSHV ORF57 and UIF provides mRNA-adaptor redundancy in herpesvirus intronless mRNA export. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002138 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bain G, Kitchens D, Yao M, Huettner JE, Gottlieb DI. 1995. Embryonic stem cells express neuronal properties in vitro. Dev. Biol. 168:342–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suvà ML, Riggi N, Stehle JC, Baumer K, Tercier S, Joseph JM, Suvà D, Clément V, Provero P, Cironi L, Osterheld MC, Guillou L, Stamenkovic I. 2009. Identification of cancer stem cells in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res. 69:1776–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Episkopou V. 2005. SOX2 functions in adult neural stem cells. Trends Neurosci. 28:219–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hu-Lieskovan S, Zhang J, Wu L, Shimada H, Schofield DE, Triche TJ. 2005. EWS-FLI1 fusion protein up-regulates critical genes in neural crest development and is responsible for the observed phenotype of Ewing's family of tumors. Cancer Res. 65:4633–4644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Riggi N, Suvà ML, Suvà D, Cironi L, Provero P, Tercier S, Joseph JM, Stehle JC, Baumer K, Kindler V, Stamenkovic I. 2008. EWS-FLI-1 expression triggers a Ewing's sarcoma initiation program in primary human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 68:2176–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. 1998. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282:1145–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Itskovitz-Eldor J, Schuldiner M, Karsenti D, Eden A, Yanuka O, Amit M, Soreq H, Benvenisty N. 2000. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies compromising the three embryonic germ layers. Mol. Med. 6:88–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A. 2003. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:183–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Macnab S, White R, Hiscox J, Whitehouse A. 2008. Production of an infectious herpesvirus saimiri-based episomally maintained amplicon system. J. Biotechnol. 134:287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ryan MD, Drew J. 1994. Foot-and-mouth-disease virus 2a oligopeptide mediated cleavage of an artificial polyprotein. EMBO J. 13:928–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna J, Saha K, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, Jaenisch R. 2009. Reprogramming of murine and human somatic cells using a single polycistronic vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:157–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. 2009. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science 324:797–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu J, Chau KF, Vodyanik MA, Jiang J, Jiang Y. 2011. Efficient feeder-free episomal reprogramming with Small molecules. PLoS One 6:e17557 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yusa K, Rad R, Takeda J, Bradley A. 2009. Generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent mouse stem cells by the piggyBac transposon. Nat. Methods 6:363–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hochedlinger K, Blelloch R, Brennan C, Yamada Y, Kim M, Chin L, Jaenisch R. 2004. Reprogramming of a melanoma genome by nuclear transplantation. Genes Dev. 18:1875–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bernhardt M, Galach M, Novak D, Utikal J. 2012. Mediators of induced pluripotency and their role in cancer cells—current scientific knowledge and future perspectives. Biotechnol. J. 7:810–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ramos-Mejia V, Fraga MF, Menendez P. 2012. iPSCs from cancer cells: challenges and opportunities. Trends Mol. Med. 18:245–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]