Abstract

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the etiologic agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), is present in the predominant tumor cells of KS, the spindle cells. Spindle cells express markers of lymphatic endothelium and, interestingly, KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells reprograms them to a lymphatic endothelial cell phenotype. KSHV-induced reprogramming requires the activation of STAT3 and phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)/AKT through the activation of cellular receptor gp130. Importantly, KSHV-induced reprogramming is specific to endothelial cells, indicating that there are additional host genes that are differentially regulated during KSHV infection of endothelial cells that contribute to lymphatic reprogramming. We found that the transcription factor Ets-1 is highly expressed in KS spindle cells and is upregulated during KSHV infection of endothelial cells in culture. The KSHV latent vFLIP gene is sufficient to induce Ets-1 expression in an NF-κB-dependent fashion. Ets-1 is required for KSHV-induced expression of VEGFR3, a lymphatic endothelial-cell-specific receptor important for lymphangiogenesis, and Ets-1 activates the promoter of VEGFR3. Ets-1 knockdown does not alter the expression of another lymphatic-specific gene, the podoplanin gene, but does inhibit the expression of VEGFR3 in uninfected lymphatic endothelium, indicating that Ets-1 is a novel cellular regulator of VEGFR3 expression. Knockdown of Ets-1 affects the ability of KSHV-infected cells to display angiogenic phenotypes, indicating that Ets-1 plays a role in KSHV activation of endothelial cells during latent KSHV infection. Thus, Ets-1 is a novel regulator of VEGFR3 and is involved in the induction of angiogenic phenotypes by KSHV.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's Sarcoma (KS) is the most common tumor of AIDS patients worldwide and occurs in posttransplant patients, as well. In parts of central Africa, KS is the most common tumor seen in hospitals, occurring in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients (1–4). KS tumors are highly vascularized, exhibiting extensive neoangiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, which is thought to be critical to the development of the tumor (5). The main cell type found within the KS tumor is the spindle cell, a cell of endothelial origin (6, 7). Specifically, KS spindle cells display markers of lymphatic endothelium, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3), podoplanin, and Prox-1 (8–10). VEGFR3 is the receptor for VEGF-C, a cytokine critical for the induction of lymphangiogenesis, the formation of new lymphatic vessels. The gene expression profile of KS spindle cells most closely matches that of isolated lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), further indicating that KS is a lymphatic endothelial cell disease (11, 12).

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the etiologic agent of KS. KSHV is a gammaherpesvirus with a genome approximately 165 kbp in length including over 90 open reading frames (ORFs). As with all herpesviruses, KSHV has both a lytic and a latent phase. During latency, only a few genes are expressed, including those encoding latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 (LANA-1), which maintains the viral episome, among other functions; viral cyclin (vCyclin, or vCyc), a cyclin D homolog; viral FLICE-inhibitory protein (vFLIP), an antiapoptotic gene that activates NF-κB; and the Kaposin family members A, B, and C, as well as numerous viral microRNAs (miRNAs) expressed from 12 loci (13–17). Other viral genes may be expressed at low levels during latency, as well (18). In cultured endothelial cells and in KS tumor cells, the virus establishes latency in over 95% of infected cells, while only 1 to 5% of the cells support lytic replication of the virus (19).

Our laboratory and others previously found that KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells leads directly to cellular reprogramming to a more lymphatic endothelial cell phenotype (11, 12, 20). During embryogenesis, the blood vessel system, lined by blood endothelial cells, forms first, and subsequently, the lymphatic vessel system, lined by lymphatic endothelial cells, forms. Blood endothelial cells in the cardinal vein are induced to differentiate into lymphatic endothelial cells to initiate this process (21, 22). KSHV induces the expression of a number of lymphatic endothelial cell-specific markers, including VEGFR3, podoplanin, LYVE-1, and the master regulator of lymphatic differentiation, Prox-1 (11, 12, 20). Our laboratory previously demonstrated that activation of AKT, through the interleukin 6 (IL-6) cytokine family transmembrane receptor gp130, leads to the expression of the lymphatic-specific markers VEGFR3, LYVE-1, podoplanin, and Prox-1 and that KSHV-induced lymphatic reprogramming requires continued latent viral gene expression (23). We recently demonstrated that the viral homolog of human IL-6 (vIL-6) is sufficient to induce lymphatic reprogramming of blood endothelial cells. However, vIL-6 is not required for blood to lymphatic endothelial cell differentiation in the context of KSHV infection (24). Therefore, other viral factors are involved in driving KSHV-induced reprogramming of blood endothelial cells. Importantly, the induction of lymphatic endothelial-cell-specific markers is observed in KSHV-infected blood endothelial cells, but not in infected cells of different origins, for example, HEK293 cells (V. A. Morris and M. Lagunoff, unpublished observations). Therefore, we sought to identify additional host genes that are differentially regulated during KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells that could contribute to lymphatic reprogramming.

The transcription factor Ets-1 is a proto-oncoprotein highly expressed in a variety of solid tumors and has been implicated in tumor invasion and progression (25–29). Ets-1 is found in a variety of cell and tissue types, including lymphocytes, fibroblasts, mesenchymal cells, and endothelial cells of the developing vasculature (30–34). Ets-1 induces angiogenic and invasive phenotypes in endothelial cells, including wound healing, cell proliferation, and cell survival during embryonic angiogenesis (35–38). Ets-1 belongs to the ETS family of transcription factors due to the presence of the ETS DNA binding domain. This domain recognizes a GGAA/T core DNA sequence. Ets-1 cooperatively interacts physically and functionally with a number of proteins and transcription factors, including AP-1, NF-κB, HIF 2α, and STAT5 (39–43). Known gene targets of Ets-1 include early growth response 1 (Egr1), Tie1 and -2, MMPs, p53, osteopontin, and VEGFR1 genes (44–50). Ets-1 is upregulated by another human gammaherpesvirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), mediated by the viral latent membrane protein 1, resulting in the upregulation of c-Met and proliferation of virus-infected epithelial cells (51). In KSHV, the latent LANA-1 gene was shown to interact with Daxx, a negative regulator of Ets-1, leading to the increased expression of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 (52). Ets-1 was previously shown to be induced by KSHV infection of endothelial cells and was necessary for the induction of the proangiogenic growth factor angiopoietin 2 (Ang2) (53). Ets-1 was also shown to be required for Ras-mediated lytic reactivation of KSHV, indicating that Ets-1 may play a role in both the latent and lytic phases of KSHV infection (54, 55).

Here, we show that Ets-1 is highly expressed in KS spindle cells and that KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells strongly upregulates Ets-1 expression at the RNA and protein levels. The KSHV latent vFLIP gene is sufficient to upregulate Ets-1 expression in an NF-κB-dependent fashion, and inhibitors of NF-κB activity also block KSHV induction of Ets-1. Knockdown of Ets-1 by small interfering RNA (siRNA) blocks KSHV induction of the lymphatic-specific growth factor receptor VEGFR3, and Ets-1 expression is sufficient to induce the VEGFR3 promoter. Upregulation of Ets-1 is independent of gp130 signaling, indicating that there are at least two distinct mechanisms required for KSHV regulation of VEGFR3. The loss of Ets-1 results in defective capillary stabilization in KSHV-infected blood endothelial cells. Additionally, the knockdown of Ets-1 in uninfected primary lymphatic endothelial cells results in a decrease in VEGFR3 expression but does not affect expression of another lymphatic-specific gene, the podoplanin gene, indicating that Ets-1 is not a global regulator of lymphatic differentiation but is specific to VEGFR3 expression. Our data demonstrate that Ets-1 is a novel regulator of VEGFR3 and likely plays an important role in KSHV activation of infected endothelial cells through the activation of multiple endothelial cell activation pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Tert immortalized microvascular endothelial (TIME) cells, LANA-expressing TIME cells, pGreen and shEts-1 TIME (a TIME cell line expressing an shRNA to Ets-1) cell lines, and primary LECs were maintained as monolayer cultures in EGM-2 medium (Lonza). HEK293 cells were maintained as monolayer cultures in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Cellgro, Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine. Stable LANA-expressing TIME cells were previously described (24). The green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing pGreen and shEts-1 TIME cell lines were created using pGreenPuro short hairpin RNA (shRNA) cloning and expression lentivector (System Biosciences). The following oligonucleotide sequence was used to create the short hairpin RNA for Ets-1: forward, 5′-GAT CCG GAT GTG AAA CCA TAT CAA CTT CCT GTC AGA TTG ATA TGG TTT CAC ATG CTT TTT G-3′; reverse, 5′-AAT TCA AAA AGG ATG TGA AAC CAT ATC AAT CTG ACA GGA AGT TGA TAT GGT TTC ACA TCC G-3′. Lentivirus was created and used to infect TIME cells, as previously described (24). Stable cell lines expressing GFP were selected for puromycin resistance in EGM-2 supplemented with 10 μg/ml of puromycin. KSHV inoculum, from BCBL-1 cells was used to infect all cell lines, as previously described (19).

KSHV and infections.

KSHV infections were performed in serum-free EBM-2 medium for 4 h, after which the medium was replaced with complete EGM-2 medium containing serum and supplements. Infection rates were assessed by immunofluorescence, using antibodies against LANA and the lytic protein ORF59. In all infections performed with wild-type KSHV, >90% of the cells were LANA positive and <1% were ORF59 positive.

Plasmids.

The lentiviral expression plasmids pSIN-MCS, containing the KSHV LANA, vFLIP, or vCyclin gene (56), and pCGSW (57), encoding GFP, have been described elsewhere. Lentiviral expression plasmids (GFP, vFLIP-hemagglutinin [HA], and mutant A57L-vFLIP-HA) were a kind gift from Thomas Schultz and have been described elsewhere (58). The Ets-1 construct (pcDNA-p51ETs-1) was a kind gift from Satoshi Yamagoe (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan).

Antibodies and reagents.

VEGFR1 and podoplanin antibodies (Abcam) and VEGFR3, gp130, and Ets-1 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and beta-actin and HA antibodies (Sigma) were used in immunoblot analysis, as described below. Rabbit polyclonal Ets-1 (Abcam ab26096), rat monoclonal (LANA-1) to KSHV ORF73 (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc.), and purified rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used in immunohistochemistry analysis, as described below. The LANA antibody used in the cell culture assays was a kind gift from Don Ganem, and the vCyclin antibody used was a rabbit polyclonal raised to the full-length vCyclin protein (Morris and Lagunoff, unpublished). The kinase inhibitor BAY11-7082 (Calbiochem) was reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) and used at the indicated concentration. IκB kinase gamma (IKKγ) NEMO binding domain (NBD) inhibitor peptide, and control peptide (Imgenex) were resuspended in DMSO and used at the indicated concentrations.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were harvested and resuspended in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, and Complete Mini protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]), and cell debris was removed after a 30-min incubation by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce), and 10 μg protein was fractionated on a 4 to 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gradient gel, transferred to Immobilon P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore), blotted with the appropriate antibody (dilutions were 1:1,000 for anti-VEGFR3, anti-VEGFR1, anti-Ets-1, anti-podoplanin, anti-gp130, and anti-HA and 1:10,000 for anti-β-actin), and subsequently probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using Amersham ECL Plus (GE Healthcare).

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from TIME cells and LECs using the NucleoSpin RNA II (Mackerey-Nagel). One hundred nanograms of total RNA was used in a SuperScript III, Platinum SYBR green, one-step quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocols with the primers for either GAPDH (glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (forward, 5′-AAG GTG AAG GTC GGA GTC AAC G-3′; reverse, 5′-TGG AAG ATG GTG ATG GGA TTT C-3′), VEGFR3 (forward, 5′-GAC AGC TAC AAG TAC GAG CAT CTG-3′; reverse 5′-CTG TCT TGC AGT CGA GCA GAA-3′), or Ets-1 (forward, 5′-TCC TGC AGA AAG AGG ATG TG-3′; reverse 5′-GCT CTG AGA ACT CCG ATG GT-3′). Relative abundances of mRNA were normalized by the delta threshold cycle method to the abundance of GAPDH, with mock-infected or control-treated cells set to 1. The error bars reflect standard errors of the means for three independent experiments.

Immunohistochemistry.

KS tumors from archived patient-derived tissue samples were obtained with appropriate institutional review board oversight, deparaffinized in xylenes, and allowed to rehydrate in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Antigen retrieval consisted of incubation of slides in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9) at 95°C in a water bath for 20 min. Primary antibodies were added overnight at room temperature (Ets-1 [1:250], Orf73 [1:400], or purified rabbit IgG [1;250]). Ets-1 antibody binding was revealed using a peroxidase-based staining kit (EnVision; Dako). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The stained tissue sections were digitized using a virtual microscope (NanoZoomer; Olympus), and images were analyzed using NDPviewer (Hamamatsu) and prepared for publication using Adobe Photoshop (CS).

Transfection of siRNA.

siRNAs specific to gp130, Ets-1, and negative-control oligonucleotides were designed and synthesized by Ambion (Austin, TX). The following oligonucleotide sequences were used: gp130 (Ambion identification [ID] no. 106709; sense, 5′-GGC AUA CCU UAA ACA AGC UdTdT-3′), Ets-1 (ID no. 146635; sense, 5′-GCA UAG AGA GCU ACG AUA GdTdT-3′), and negative-control siRNA (sense, 5′-AGU ACU GCU UAC GAU ACG GdTdT-3′). TIME cells or LECs were transfected with 3 μg of siRNA using Amaxa's (Cologne, Germany) Nucleofector kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were mock or KSHV infected and subsequently harvested for analysis after an additional 48 h. LECs transfected with siRNA were harvested 48 h posttransfection for analysis.

Promoter luciferase assay.

TIME or HEK293 cells were seeded in a 6-well tissue culture dish and transfected with VEGFR1, VEGFR3, or an empty-promoter firefly luciferase construct (Switchgear Genomics), along with an empty-vector control or an Ets-1 construct. Renilla luciferase was used to normalize transfection efficiency between samples. TIME cells were transfected using TransIT-Jurkat reagent (Mirus), and HEK293 cells were transfected using TransIT-293 reagent (Mirus). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the cells were lysed and analyzed by Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luciferase expression was measured using a Glomax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega) and reported as the fold increase in luciferase expression of Ets-1 compared to empty vector. The error bars reflect standard errors of the mean of five independent experiments.

Three-dimensional culture of endothelial cells.

Matrigel (10 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) was applied at 0.5 ml/35 mm in a tissue culture dish and incubated at 37°C for at least 30 min to harden. Mock- or KSHV-infected cells were removed using trypsin-EDTA and resuspended at 1.5 × 105 cells per ml in growth medium. One milliliter of cells was gently added to the Matrigel-coated plates; incubated at 37°C; monitored at 4, 6, and 24 h; and photographed in digital format using a Nikon microscope. Capillaries were defined as cellular processes connecting two bodies of cells.

RESULTS

Ets-1 is highly expressed in the KS tumor.

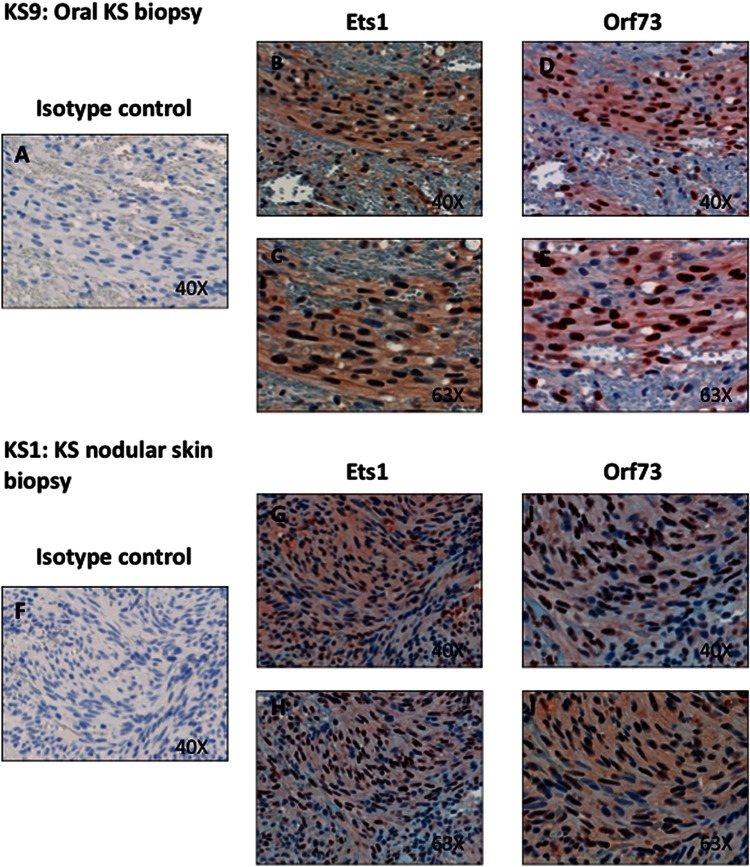

Previous studies demonstrated that KS tumor spindle cells express high levels of Ang2, a gene shown to be upregulated by KSHV infection of macrovascular endothelial cells in an Ets-1-dependent fashion (53). However, it has not been shown whether Ets-1 itself was expressed in KS spindle cells. We obtained unstained tissue sections derived from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples from 4 KS patients with confirmed histopathologic diagnosis of KS and immunostained them with antibodies to LANA and Ets-1 (Fig. 1). Two of the tumors were from the oral cavity, and two were nodular KS skin lesions. Shown in Fig. 1 is one oral cavity nodule tumor (Fig. 1A to E) and one skin nodule (Fig. 1F to J). In tumors from all four patients, there was high-level staining with the Ets-1 antibody. Importantly, throughout the four biopsy samples, it is clear that there was strong Ets-1 staining in the regions where there were high levels of LANA staining (predominantly spindle cells), while in regions of the biopsy specimen where there was little or no LANA nuclear staining, only a very low percentage of the cells stained with the Ets-1 antibody. In the spindle cells, Ets-1 stains throughout the cell with high levels of nuclear staining, as indicated by the very dark-staining nuclei, with some cytoplasmic staining, as indicated by the light cytoplasmic staining. In cells from areas of the biopsy specimens that did not stain for LANA, there was little or no staining seen for Ets-1. Whole-cell staining of Ets-1 has previously been demonstrated in gastric, breast, and colorectal carcinomas (27, 59–61). Ets-1, located in the nucleus, is bound to DNA, while overproduced Ets-1 localizes to the cytoplasm (61). In summary, Ets-1 stains strongly in KS tumor cells in regions where there are high levels of spindle cells that express LANA, indicating that Ets-1 is highly expressed in KS spindle cells.

Fig 1.

Ets-1 is highly expressed in LANA-positive regions of KS tumors. Serial KS tumor sections were stained with antibodies to Ets-1 isotype control rabbit IgG, KSHV Orf 73 (LANA), or Ets-1 and counterstained with hematoxylin. (A to E) Magnifications (×40 and ×63) of serial sections of an oral KS nodule biopsy specimen from the right maxillary gingiva are shown with the same regions aligned and are representative of staining seen in 2 different oral KS nodules. (F to J) Magnifications (×40 and ×63) of the same aligned regions of a nodular KS skin biopsy specimen are shown and are representative of staining seen in 2 different KS skin biopsy specimens.

Ets-1 is upregulated during KSHV infection.

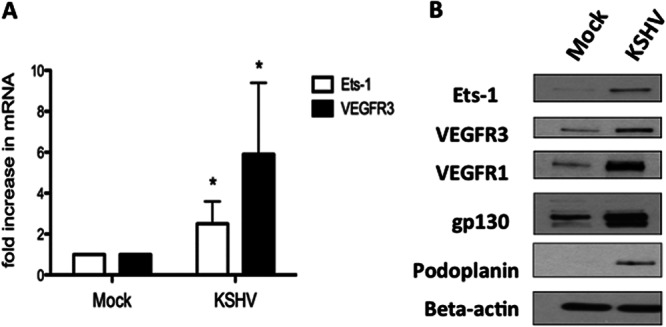

It was previously reported that Ets-1 is upregulated during KSHV infection (53). Analysis of our microarray studies comparing mock- and KSHV-infected endothelial cells also indicated that Ets-1 was significantly upregulated in our KSHV-infected samples (data not shown). We confirmed this result in TIME cells and primary dermal microvascular endothelial cells (DMVECs) using quantitative real-time RT-PCR to measure transcript levels of Ets-1. Cells were mock or KSHV infected for 48 h, which allows the establishment of latency in the KSHV-infected cells, and total mRNA was extracted and used to measure transcript levels by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. KSHV-infected TIME cells have elevated Ets-1 transcript levels, approximately 3.5-fold higher than mock-infected cells, and Ets-1 mRNA levels were similarly elevated in KSHV-infected primary dermal microvascular endothelial cells (Fig. 2A and data not shown). VEGFR3 mRNA is upregulated 6-fold in KSHV-infected TIME cells compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 2A), as we have described previously (20, 23). We next examined the protein expression levels of both Ets-1 and VEGFR3 using Western blot analysis. Ets-1 and VEGFR3 protein levels are significantly higher in TIME cells latently infected with KSHV (Fig. 2B) than in mock-infected cells. Importantly, in the KSHV-infected samples, at least 95% of the cells express the latent LANA gene, while fewer than 1% express ORF59, a marker of lytic infection in all experiments used, indicating that the effects seen are predominantly due to latent infection.

Fig 2.

KSHV upregulates Ets-1 in endothelial cells. TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected for 48 h in order to establish latency. (A) Cells were harvested, and mRNA was isolated and analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Samples were normalized to GAPDH and are reported as fold change over mock-infected cells. The error bars reflect standard errors of the mean of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (B) Forty-eight hours postinfection, mock- and KSHV-infected TIME cells were harvested, and cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Ets-1, VEGFR1, VEGFR3, gp130, podoplanin, and beta-actin as a loading control.

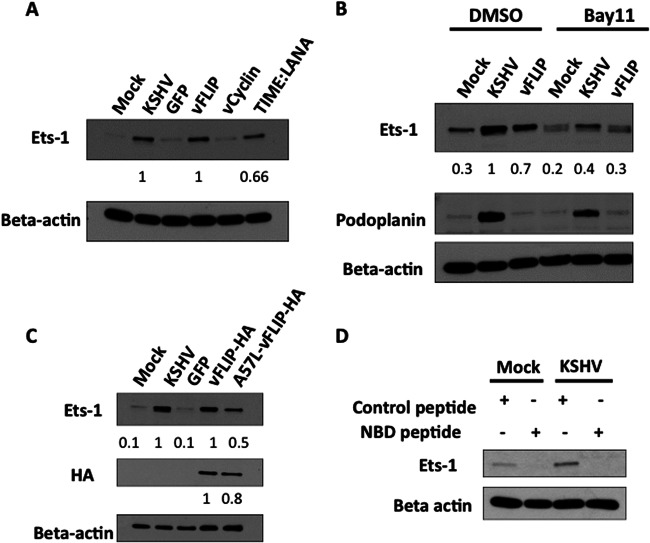

KSHV vFLIP is sufficient to induce Ets-1.

Because Ets-1 upregulation occurs predominantly during latent infection, we asked if a single latent viral gene could lead to Ets-1 expression. We transiently expressed the KSHV latent LANA, vFLIP, and vCyclin genes in TIME cells using lentiviral expression vectors, and we also utilized a TIME cell line that was infected with the LANA-expressing lentivirus and was selected for long-term high-level expression of LANA. TIME cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing KSHV genes, and 48 h postinfection, RNA was harvested from cells and subjected to real-time RT-PCR. RT-PCR with primers to LANA, vFLIP, and vCyclin was able to detect transcripts for each of the individual lentiviral constructs tested (data not shown). Western blot analysis of LANA and vCyclin indicated that vCyclin was expressed at higher levels than in KSHV-infected cells but the transient expression of LANA was lower than in KSHV-infected cells (data not shown). Therefore, we used the LANA-expressing TIME cell line in subsequent experiments where we demonstrated high-level expression. We were unable to compare protein expression of vFLIP in lentivrius-transduced cells to that in KSHV-infected cells due to the lack of an appropriate antibody. However, we demonstrated vFLIP expression both by real-time RT-PCR and by demonstrating activation of NF-κB in vFLIP-transduced cells (data not shown). Cells expressing vCyc and low levels of LANA from the lentivirus showed no significant increase in Ets-1 expression, while there was a significant increase in Ets-1 expression in cells transduced with the lentivirus expressing vFLIP. The LANA-expressing cells that were selected for high expression levels of LANA also yielded increases in Ets-1 protein levels (Fig. 3A). Our results with LANA are in agreement with a previous study that reported that LANA interacts with an inhibitor of Ets-1, Daxx, during KSHV infection (52). Currently, we cannot rule out the possibility that other viral genes or miRNAs may also be able to induce expression of Ets-1 during latency. However, these data indicate that the latent vFLIP gene is sufficient to induce Ets-1 and, when selected for high-level expression, LANA is also sufficient to induce Ets-1.

Fig 3.

The latent vFLIP gene induces Ets-1 expression through NF-κB activity. (A) TIME cells were either mock or KSHV infected or infected with lentivirus containing GFP or the latent vFLIP and vCyclin genes for 48 h, and cell lysates were harvested. TIME cells stably expressing LANA were also harvested, and all cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies directed to Ets-1 or beta-actin as a loading control. Both KSHV infection and expression of the individual latent vFLIP and LANA genes induce Ets-1 expression. (B) TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected or infected with lentivirus expressing the latent vFLIP gene; 24 h postinfection, the cells were treated with either a vehicle control (DMSO) or an inhibitor of NF-κB (Bay11-7082; 5 μM). At 48 h postinfection, cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. KSHV-infected TIME cells treated with Bay11-7082 displayed a 2.5-fold decrease in Ets-1 expression compared to KSHV-infected cells treated with DMSO. vFLIP-transduced TIME cells displayed a 2.3-fold decrease in Ets-1 expression when treated with Bay11-7082 compared to DMSO treatment. (A and B) Ets-1 protein data were quantitated using ImageJ and are shown below the Ets-1 gel. (C) TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected or transduced with lentivirus expressing either GFP, vFLIP-HA, or the NF-κB activation-deficient mutant A57L-vFLIP-HA. After 48 h, cells were harvested, and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies directed to Ets-1 and beta-actin as a loading control. vFLIP and A57L-vFLIP expression was detected with an antibody to the HA tag. The data were quantitated using ImageJ and are displayed below the HA gel. KSHV and vFLIP-HA induce Ets-1 expression, while A57L-vFLIP-HA displays an approximately 50% reduced ability to induce Ets-1 expression. A57L-vFLIP was expressed to over 80% of wild-type levels. The data were quantitated using ImageJ and are displayed below the Ets-1 gel. (D) TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected and treated with either a control peptide or IKKγ NBD inhibitory peptide 24 h postinfection at a final concentration of 50 μM. Twenty-four hours posttreatment, cells were harvested, and cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to Ets-1 and beta-actin as a loading control.

KSHV vFLIP protects cells from apoptosis through the activation of the NF-κB pathway. To determine if vFLIP upregulates Ets-1 through the NF-κB pathway, we expressed vFLIP as before, except at 24 h after lentivirus infection, we treated the cells with the NF-κB inhibitor Bay11-7082. As demonstrated in Fig. 3B, the NF-κB inhibitor reproducibly abrogated the ability of vFLIP to induce Ets-1 in multiple experiments. We also used a vFLIP construct, A57L-vFLIP-HA, that contains a point mutation yielding decreased NF-κB activation (58). When transduced into TIME cells, the mutant was expressed to over 80% of wild-type levels in two experiments, while Ets-1 expression levels were approximately 50% those of the wild-type transductants, indicating that the mutant was unable to induce Ets-1 expression to wild-type vFLIP levels (Fig. 3C).

To determine if KSHV activation of Ets-1 is also dependent on NF-κB, at 24 h postinfection with KSHV, we treated TIME cells with Bay11-7082 and harvested cells at 48 h postinfection. Inhibition of NF-κB blocked the induction of Ets-1 by KSHV, indicating that, as with vFLIP, KSHV requires NF-κB for the induction of Ets-1 (Fig. 3B). In order to confirm this result, we used a NEMO binding peptide inhibitor (NBD peptide) to specifically block NF-κB activation during KSHV infection. TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected, and 24 h postinfection, the cells were treated with 50 μM control peptide or NBD peptide. Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection, and the levels of Ets-1 protein expression were analyzed by Western blotting. As seen in Fig. 3D, the NBD peptide blocked the expression of Ets-1 in both mock- and KSHV-infected cells. The control peptide had no effect on Ets-1 expression, and there was no noticeable toxicity with either peptide. Therefore, the vFLIP gene is likely the predominant viral gene inducing Ets-1 during KSHV latent infection. Additionally, another cellular gene known to be induced by KSHV, the podoplanin gene, was not significantly altered by Bay11-7082 treatment (Fig. 3B), indicating that in the presence of this inhibitor, KSHV was still able to activate cellular proteins.

Ets-1 regulates expression of the lymphatic-specific VEGFR3 gene.

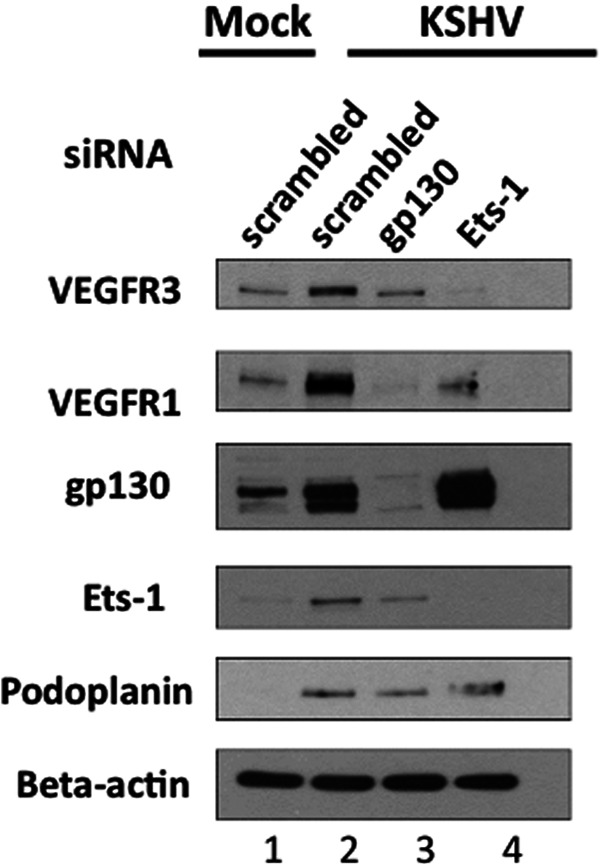

To determine the role of Ets-1 during infection and to explore host genes controlled by Ets-1 during KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells, we knocked down Ets-1 expression with siRNAs directed specifically to Ets-1 sequences. TIME cells were transfected with Ets-1 siRNA, gp130 siRNA, or a control nonspecific siRNA. The cells were subsequently mock or KSHV infected 24 h posttransfection, and cell extracts were harvested 48 h postinfection for Western blot analysis. The siRNA directed to Ets-1 efficiently knocked down Ets-1 expression in KSHV-infected cells to mock-infected-cell levels (Fig. 4). Ets-1 knockdown results in a loss of VEGFR1, a growth factor receptor previously shown to be regulated by Ets-1. Interestingly, expression of the lymphatic-specific VEGFR3 gene was also knocked down by Ets-1 siRNA in KSHV-infected cells. We previously reported that activation of gp130 by KSHV is required for lymphatic reprogramming and for the expression of lymphatic-specific Prox-1, podoplanin, LYVE-1, and VEGFR3 genes (23). Knockdown of gp130 by siRNA results in a decrease in VEGFR1, VEGR3, and podoplanin but does not significantly alter the expression levels of Ets-1 (Fig. 4). This suggests that upregulation of Ets-1 by KSHV and Ets-1 control of VEGFR3 are independent of gp130 signaling. Interestingly, knockdown of Ets-1 appears to slightly increase expression of gp130. While the mechanism of gp130 upregulation when Ets-1 is knocked down is not clear, this provides further evidence that Ets-1 induction of VEGFR3 is a separate pathway from gp130 activation.

Fig 4.

Ets-1 induction by KSHV is necessary for VEGFR3 expression. TIME cells were transfected with control, gp130, or Ets-1 siRNA with the Amaxa kit and 24 h posttransfection were mock or KSHV infected. Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection, and cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. While gp130 siRNA knocks down KSHV-induced gp130, VEGFR1, VEGFR3, and podoplanin expression, Ets-1 siRNA decreases KSHV-induced expression of Ets-1, VEGFR1, and VEGFR3, but not podoplanin.

While Ets-1 knockdown decreases expression of VEGFR3, it does not significantly alter the expression of another lymphatic-specific gene, the podoplanin gene, indicating that Ets-1 is not a global regulator of lymphatic gene expression but is specific to the lymphatic endothelial VEGFR3 gene (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data suggest that activation of the transcription factor Prox-1 through gp130 signaling is required for lymphatic differentiation of blood endothelial cells and expression of VEGFR3, while Ets-1 is necessary for the optimal expression of VEGFR3, but not lymphatic reprogramming of blood endothelial cells (see Discussion).

Ets-1 activates the VEGFR3 promoter.

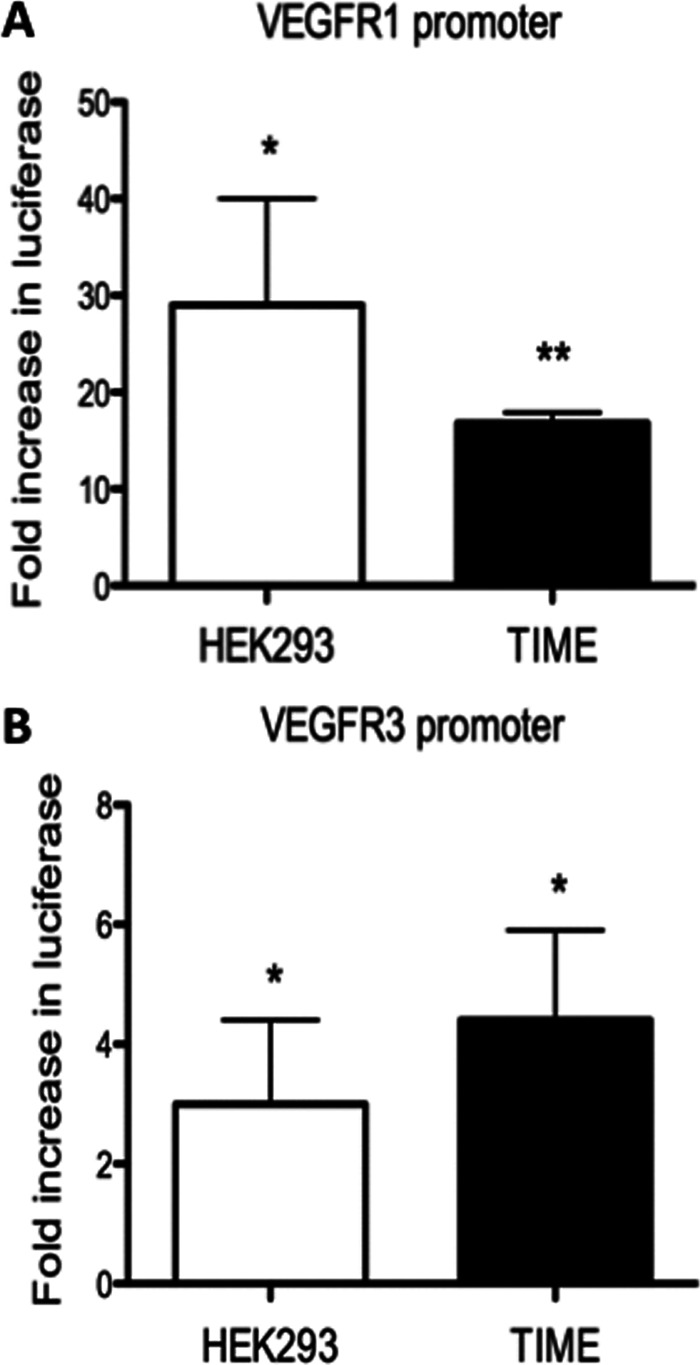

Ets-1 is a transcription factor known to induce the expression of growth factors and has been reported to directly activate the promoter of VEGFR1 (35, 40, 45, 48). Therefore, we next examined the ability of Ets-1 to activate the promoter of VEGFR3. Firefly luciferase reporter constructs driven by either the VEGFR1 or VEGFR3 promoter were transfected into HEK293 and TIME cells. A construct containing the full-length Ets-1 protein was tested for the ability to increase luciferase production compared to empty-vector transfection in both cell types. A plasmid construct with the Renilla luciferase gene under the control of the thymidine kinase promoter was cotransfected and used to normalize for transfection efficiency. Ets-1 is able to strongly activate the VEGFR1 promoter driving luciferase production in both HEK293 and TIME cells, confirming that Ets-1 activates the VEGFR1 promoter, as shown in Fig. 5A, where the average induction from five separate biological replicate experiments is shown. Ets-1 expression is also able to activate the VEGFR3 promoter and increase luciferase production 3-fold in HEK293 cells and 4.5-fold in TIME cells (Fig. 5B). Ets-1 regulation of the expression and promoters of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 has been described previously. This is the first report that Ets-1 regulates the promoter of the lymphatic endothelial-cell-specific growth receptor, VEGFR3.

Fig 5.

Ets-1 activates the VEGFR1 and VEGFR3 promoters. Luciferase reporter constructs with the VEGFR1 (A) or VEGFR3 (B) promoter driving firefly luciferase expression were transfected into TIME and HEK293 cells with either an empty vector or an Ets-1 expression plasmid. A Renilla luciferase reporter construct was cotransfected and used as a control for transfection efficiency. The graph indicates the fold increase in relative (firefly/Renilla) luciferase expression of the VEGFR1 or VEGFR3 promoter constructs in the presence of Ets-1 expression vector versus the empty-vector control. The error bars reflect standard errors of the mean of five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

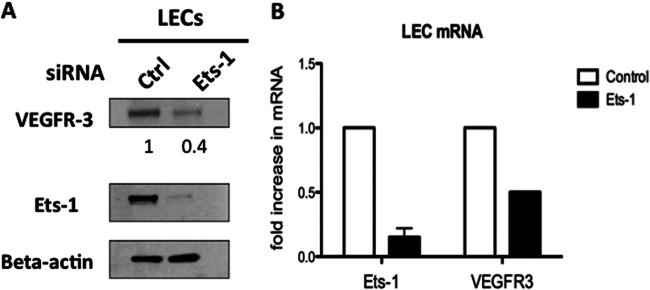

Ets-1 controls VEGFR3 expression in uninfected primary lymphatic endothelial cells.

We next wanted to determine if physiological levels of Ets-1 control VEGFR3 in primary lymphatic endothelial cells, where there are high levels of VEGFR3 expression. We transduced primary lymphatic endothelial cells with a plasmid expressing control or Ets-1-specific siRNA and performed Western blot analysis on cell lysates. Ets-1 siRNA efficiently knocked down expression of Ets-1 in LECs, demonstrating the efficacy of the siRNA used. Knockdown of Ets-1 led to a decrease in VEGFR3 protein expression by approximately 50% (Fig. 6A). Using real-time RT-PCR, VEGFR3 mRNA levels were decreased 2-fold and Ets-1 mRNA was decreased 6-fold in LECs treated with Ets-1 siRNA (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that Ets-1 is a global regulator of VEGFR3 expression and that it may play a role in the sustained expression of VEGFR3 in lymphatic vasculature.

Fig 6.

High-level VEGFR3 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells requires Ets-1. Primary lymphatic endothelial cells were transfected with the Amaxa kit with either a control siRNA or Ets-1 siRNA. (A) Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. VEGFR3 protein data were quantitated using ImageJ, comparing cells transfected with Ets-1 siRNA versus control siRNA, and are shown below the VEGFR3 gel. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to analyze Ets-1 and VEGFR3 mRNA expression levels of control siRNA- or Ets-1 siRNA-transfected LECs 48 h posttransfection. The data are reported as fold change in mRNA of Ets-1 siRNA versus control siRNA. The error bar reflects the standard error of the mean of three independent experiments.

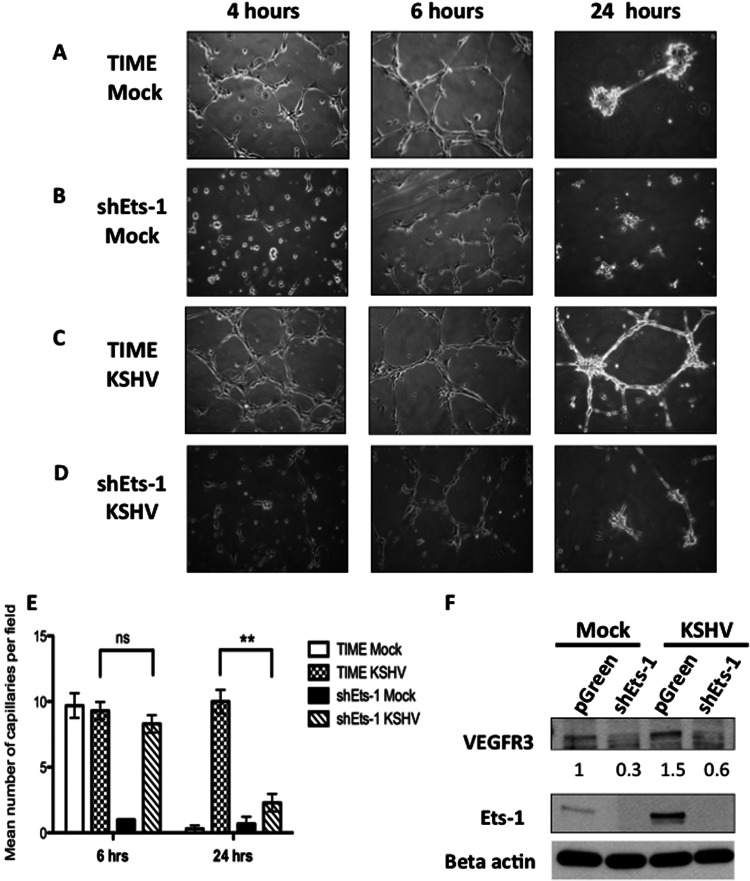

Loss of Ets-1 results in defective capillary morphogenesis of KSHV-infected endothelial cells.

It was previously reported that KSHV leads to stabilization of endothelial tubule formation at 24 h after plating in a three-dimensional matrix (62–64). Ets-1 has been described as a proangiogenic factor that activates genes that contribute to various stages of the angiogenic process, such as matrix metalloproteases, Ang1 and -2, and Tie1 and -2 (30, 34). This suggests that Ets-1 may play a functional role in the ability of KSHV-infected endothelial cells to induce angiogenic phenotypes. For these studies, we created TIME cell lines with an shRNA specific to Ets-1 and a control vector-only cell line expressing GFP. The protein level of Ets-1 is significantly knocked down in both mock- and KSHV-infected cells with the Ets-1 shRNA compared to the control cell line, and as expected from the above description, VEGFR3 expression is also decreased (Fig. 7E). Infection levels of both control (pGreen) and Ets-1 shRNA (shEts-1) cell lines were not significantly different as measured by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to determine the percentage of cells expressing LANA (data not shown). To investigate the angiogenic role of Ets-1, we mock and KSHV infected the shEts-1 cell line and tested the ability of these cells to organize and form capillary-like structures in a three-dimensional culture on Matrigel. Mock-infected TIME cells began to spread in the Matrigel by 4 h postplating and formed capillary structures by 6 h. The shEts-1 knockdown cells demonstrated a delay in cell spreading but formed similar numbers of capillary-like structures by 6 h postplating. However, in both cell lines, the majority of capillary-like connections regressed by 24 h and no longer formed a structured network (Fig. 7A and B; quantified in Fig. 7E). KSHV-infected TIME cells are able to attach and form capillary-like structures in Matrigel, similar to the uninfected cells. However, unlike the uninfected cells, at 24 h postplating in Matrigel, intact capillary-like networks were still present, suggesting KSHV promotes a prolonged angiogenic phenotype (Fig. 7C; quantified in Fig. 7E), as seen previously (63, 64). Interestingly, KSHV-infected shEts-1 knockdown TIME cells did not exhibit capillary-like structures 24 h postplating (Fig. 7D). These data suggest that Ets-1 contributes to the ability of KSHV-infected cells to display enhanced angiogenic phenotypes.

Fig 7.

Ets-1 contributes to the angiogenic phenotype of KSHV-infected endothelial cells. (A to D) TIME cells and shEts-1-transduced TIME cells were mock or KSHV infected. Forty-eight hours postinfection, the cells were plated on a Matrigel 3-dimensional matrix and incubated at 37°C. Representative capillary morphogenesis pictures taken at 4, 6, and 24 h postplating are shown. (E) Quantitation of capillaries from three independent experiments similar to the one seen in panels A to D. Three fields from each experiment (9 total) were analyzed, and the numbers of capillaries per field were determined. The error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean of three independent experiments. ns, not significant; **, P < 0.005 (evaluated by Student's t test). (F) Western blot of a TIME cell line expressing an shRNA to Ets-1 (shEts-1) and a control cell line (pGreen) mock and KSHV infected for 48 h. The control pGreen cell line displayed results similar to those for TIME cells, where infection with KSHV increased expression of Ets-1 and VEGFR3. The mock- and KSHV-infected shEts-1 cell line showed efficient knockdown of both Ets-1 and VEGFR3. VEGFR3 protein data were quantitated using ImageJ and are shown below the VEGFR3 gel.

DISCUSSION

Ets-1 is highly expressed in many solid tumors and is associated with tumor progression and invasion (26, 28, 29). Ets-1 is also present at high levels in the developing vasculature and is associated with tumor vasculature. KS spindle cells are endothelial in origin and therefore have many activated endothelial cell phenotypes common to angiogenesis and to tumor formation. A previous study examining gene expression of KS tumors by microarray found that there were high levels of Ets-1 mRNA in tumor biopsy specimens (65). However, the KS tumor consists of multiple cell types, and therefore, we examined protein expression by immunohistochemistry. We found that there are high levels of Ets-1 expression in LANA-positive KS spindle cells, as well as in some of the cells lining the vascular slits in the tumor, indicating that Ets-1 expression is associated with both the increased vascularization of KS tumors and the tumor cells themselves. Therefore, Ets-1 may play an important role in KS tumor initiation and progression.

Previous studies have shown that Ets-1 expression is increased by KSHV infection of cultured endothelial cells (53, 65). Additionally, it was shown that KSHV infection of lymphatic endothelial cells decreased the expression of two cellular miRNAs that could downregulate Ets-1 (65). Our cell culture models of latent KSHV infection confirmed previous studies showing that KSHV infection of endothelial cells significantly increased Ets-1 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (53, 65). While this does not demonstrate a direct correlation between KSHV gene expression and high levels of Ets-1 in the KS spindle cells, it is suggestive that KSHV latent gene expression plays a role in the high levels of Ets-1 expression in the tumor. In endothelial cells, the latent vFLIP gene was sufficient to induce expression of Ets-1 in an NF-κB-dependent fashion. An endothelial cell line expressing high levels of LANA also showed some induction of Ets-1; however, transient expression of LANA was not sufficient to induce Ets-1 (data not shown). Importantly, inhibition of NF-κB by the pharmacological inhibitor Bay11-7082 or with NEMO binding inhibitory peptides blocked KSHV-induced Ets-1 expression. Because NF-κB activation is necessary for KSHV induction of Ets-1 and vFLIP activation of NF-κB is sufficient for induction of Ets-1, vFLIP is likely the dominant KSHV activator of Ets-1 expression during latent infection, and the role of LANA induction may be auxiliary or needed for maximal expression.

Ets-1 regulates genes involved in many different cellular processes, such as migration, proliferation, and apoptosis (30, 36, 37). We found that KSHV-induced Ets-1 expression was necessary for the full induction of VEGFR3. VEGFR3 is the receptor for VEGFC, a cytokine important for the growth and differentiation of lymphatic endothelium. VEGFR3 expression is switched on during blood to lymphatic endothelial cell differentiation. We and others previously showed that KSHV infection of blood endothelial cells induces reprogramming to lymphatic endothelium and the expression of VEGFR3 (11, 12, 20). During development, this process is known to require Prox-1, which activates VEGFR3, among many other lymphatic-specific genes. While Ets-1 is necessary for the full induction of VEGFR3 by KSHV, knockdown of Ets-1 did not completely abrogate VEGFR3 expression, likely due to KSHV-induced expression of Prox-1. Interestingly, podoplanin, another lymphatic endothelial cell-specific gene, is highly induced by KSHV, even when Ets-1 is blocked, indicating that Ets-1 is specific to VEGFR3 and is not involved in overall lymphatic reprogramming. A previous study in macrovascular endothelial cells showed that Prox-1 acts synergistically with Ets-2 to induce lymphangiogenesis and that Ets-2, and to a much lesser extent Ets-1, can bind to Prox-1 and potentiate its activation of VEGFR3 (66). We found that Ets-1 activates the promoter of VEGFR3 in the absence of Prox-1 expression in endothelial cells, as well as in nonendothelial cells; however, relatively little is known about the regulation of the VEGFR3 promoter. While it is not currently known if Ets-1 directly binds to the VEGFR3 promoter, we identified two consensus Ets-1 binding sites upstream of the VEGFR3 TATA box. Further work to discover if these sequences are involved in Ets-1 activation of the VEGFR3 promoter is necessary to determine if there is direct activation. However, it is not clear if Ets-1 expression alone is enough to activate VEGFR3 from its native promoter. It is possible that VEGFR3 may need to be turned on by other factors and that Ets-1 boosts expression of VEGFR3 through activation of an open promoter. KSHV also induces Prox-1 in blood endothelial cells, and therefore, Prox-1 and Ets-1 could synergize to induce the VEGFR3 promoter in KSHV-infected cells to achieve optimal VEGFR3 expression. This was reported to be the case in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (66). However, in TIME cells or HEK293 cells, Prox-1 did not synergistically increase VEGFR3 promoter activation by Ets-1 (data not shown). Further work to understand the interactions of Ets-1 and Prox-1 in microvascular endothelial cells and how the two factors activate VEGFR3 is warranted. Importantly, knockdown of Ets-1 in primary lymphatic endothelial cells also led to a significant decrease in VEGFR3 expression, indicating that Ets-1 is necessary for high-level VEGFR3 expression in naturally differentiated lymphatic endothelium. While it has been reported that Ets-1 is required for embryonic endothelial cell survival, Ets-1 is apparently not required for survival of differentiated endothelial cells, as we were able to create a stable shRNA Ets-1 knockdown cell line (38). As VEGFR3 is critical for growth of lymphatic endothelium, Ets-1 expression is, by correlation, likely to be important for growth of lymphatic endothelium, as well.

We and others have reported that KSHV infection promotes cell survival and proliferation and supports angiogenic phenotypes, such as capillary formation (62–64). Ets-1 clearly plays a role in KSHV-induced angiogenesis. We found that Ets-1 activates VEGFR3 and VEGFR1 in KSHV-infected endothelial cells, and previously, others reported that Ets-1 induction leads to upregulation of Ang2 (53). All of these genes play roles in the induction of angiogenesis and/or lymphangiogenesis. We found that Ets-1 was shown to have a direct role in the ability of KSHV to stabilize and prolong endothelial capillary-like tube formation in Matrigel. Thus, Ets-1 plays a direct role in the induction of angiogenic phenotypes by KSHV. Whether this is through VEGFR3, VEGFR1, or Ang2 regulation is under investigation. Regardless, it is apparent that Ets-1 is highly expressed in KS spindle cells and that KSHV induction of Ets-1 by vFLIP is likely to play a direct role in the formation of this endothelial cell-based tumor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas Schultz (Institute of Virology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany) for providing the vFLIP-HA and mutant A57L-vFLIP-HA lentiviral vectors, Satoshi Yamagoe (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) for the Ets-1 expression plasmid, and Sreetha Sidharthan for technical assistance.

K.D.G. was supported by a National Institutes of Health CFAR STD/AIDS predoctoral training fellowship (T32AI07140). M.L. and S.B. were supported by a grant from the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (PO1DE021954), and M.L. was also supported by a grant from the National cancer institute (RO1CA097934).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Antman K, Chang Y. 2000. Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1027–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganem D. 2006. KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi's sarcoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1:273–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Senba M, Buziba N, Mori N, Morimoto K, Nakamura T. 2011. Increased prevalence of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in the Kaposi's sarcoma-endemic area of western Kenya in 1981–2000. Acta Virol. 55:161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wahman A, Melnick SL, Rhame FS, Potter JD. 1991. The epidemiology of classic, African, and immunosuppressed Kaposi's sarcoma. Epidemiol. Rev. 13:178–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dimaio TA, Lagunoff M. 2012. KSHV induction of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic phenotypes. Front. Microbiol. 3:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Regezi JA, MacPhail LA, Daniels TE, DeSouza YG, Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated oral Kaposi's sarcoma. A heterogeneous cell population dominated by spindle-shaped endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 143:240–249 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Staskus KA, Zhong W, Gebhard K, Herndier B, Wang H, Renne R, Beneke J, Pudney J, Anderson DJ, Ganem D, Haase AT. 1997. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J. Virol. 71:715–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jussila L, Valtola R, Partanen TA, Salven P, Heikkilä P, Matikainen MT, Renkonen R, Kaipainen A, Detmar M, Tschachler E, Alitalo R, Alitalo K. 1998. Lymphatic endothelium and Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells detected by antibodies against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3. Cancer Res. 58:1599–1604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skobe M, Brown LF, Tognazzi K, Ganju RK, Dezube BJ, Alitalo K, Detmar M. 1999. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) and its receptors KDR and flt-4 are expressed in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 113:1047–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weninger W, Partanen TA, Breiteneder-Geleff S, Mayer C, Kowalski H, Mildner M, Pammer J, Stürzl M, Kerjaschki D, Alitalo K, Tschachler E. 1999. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 and podoplanin suggests a lymphatic endothelial cell origin of Kaposi's sarcoma tumor cells. Lab. Invest. 79:243–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong YK, Foreman K, Shin JW, Hirakawa S, Curry CL, Sage DR, Libermann T, Dezube BJ, Fingeroth JD, Detmar M. 2004. Lymphatic reprogramming of blood vascular endothelium by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat. Genet. 36:683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang HW, Trotter MW, Lagos D, Bourboulia D, Henderson S, Makinen T, Elliman S, Flanagan AM, Alitalo K, Boshoff C. 2004. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-induced cellular reprogramming contributes to the lymphatic endothelial gene expression in Kaposi sarcoma. Nat. Genet. 36:687–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez CM, Damania B, Cullen BR. 2005. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5570–5575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaudhary PM, Jasmin A, Eby MT, Hood L. 1999. Modulation of the NF-kappa B pathway by virally encoded death effector domains-containing proteins. Oncogene 18:5738–5746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dittmer D, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Staskus K, Haase A, Ganem D. 1998. A cluster of latently expressed genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 72:8309–8315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kedes DH, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Ganem D. 1997. Identification of the gene encoding the major latency-associated nuclear antigen of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Clin. Invest. 100:2606–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sadler R, Wu L, Forghani B, Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, Ganem D. 1999. A complex translational program generates multiple novel proteins from the latently expressed kaposin (K12) locus of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 73:5722–5730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chandriani S, Ganem D. 2010. Array-based transcript profiling and limiting-dilution reverse transcription-PCR analysis identify additional latent genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 84:5565–5573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lagunoff M, Bechtel J, Venetsanakos E, Roy AM, Abbey N, Herndier B, McMahon M, Ganem D. 2002. De novo infection and serial transmission of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured endothelial cells. J. Virol. 76:2440–2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carroll PA, Brazeau E, Lagunoff M. 2004. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of blood endothelial cells induces lymphatic differentiation. Virology 328:7–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oliver G, Alitalo K. 2005. The lymphatic vasculature: recent progress and paradigms. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:457–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oliver G, Harvey N. 2002. A stepwise model of the development of lymphatic vasculature. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 979:159–165, 188–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris VA, Punjabi AS, Lagunoff M. 2008. Activation of Akt through gp130 receptor signaling is required for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced lymphatic reprogramming of endothelial cells. J. Virol. 82:8771–8779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morris VA, Punjabi AS, Wells RC, Wittkopp CJ, Vart R, Lagunoff M. 2012. The KSHV viral IL-6 homolog is sufficient to induce blood to lymphatic endothelial cell differentiation. Virology 428:112–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujimoto J, Aoki I, Toyoki H, Khatun S, Sato E, Sakaguchi H, Tamaya T. 2004. Clinical implications of expression of ETS-1 related to angiogenesis in metastatic lesions of ovarian cancers. Oncology 66:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahne JC, Okuducu AF, Sahin A, Fafeur V, Kiriakidis S, Wernert N. 2008. The transcription factor ETS-1: its role in tumour development and strategies for its inhibition. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 8:1095–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakayama T, Ito M, Ohtsuru A, Naito S, Nakashima M, Fagin JA, Yamashita S, Sekine I. 1996. Expression of the Ets-1 proto-oncogene in human gastric carcinoma: correlation with tumor invasion. Am. J. Pathol. 149:1931–1939 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oikawa T. 2004. ETS transcription factors: possible targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 95:626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saeki H, Kuwano H, Kawaguchi H, Ohno S, Sugimachi K. 2000. Expression of ets-1 transcription factor is correlated with penetrating tumor progression in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer 89:1670–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dittmer J. 2003. The biology of the Ets1 proto-oncogene. Mol. Cancer 2:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fujimoto J, Aoki I, Toyoki H, Khatun S, Sato E, Tamaya T. 2003. Expression of ETS-1 related to angiogenesis in uterine endometrium during the menstrual cycle. J. Biomed. Sci. 10:320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hahne JC, Okuducu AF, Fuchs T, Florin A, Wernert N. 2011. Identification of ETS-1 target genes in human fibroblasts. Int. J. Oncol. 38:1645–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lian RH, Kumar V. 2002. Murine natural killer cell progenitors and their requirements for development. Semin. Immunol. 14:453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sato Y. 2001. Role of ETS family transcription factors in vascular development and angiogenesis. Cell Struct. Funct. 26:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russell L, Garrett-Sinha LA. 2010. Transcription factor Ets-1 in cytokine and chemokine gene regulation. Cytokine 51:217–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sato Y. 1998. Transcription factor ETS-1 as a molecular target for angiogenesis inhibition. Hum. Cell 11:207–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sato Y, Teruyama K, Nakano T, Oda N, Abe M, Tanaka K, Iwasaka-Yagi C. 2001. Role of transcription factors in angiogenesis: Ets-1 promotes angiogenesis as well as endothelial apoptosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 947:117–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wei G, Srinivasan R, Cantemir-Stone CZ, Sharma SM, Santhanam R, Weinstein M, Muthusamy N, Man AK, Oshima RG, Leone G, Ostrowski MC. 2009. Ets1 and Ets2 are required for endothelial cell survival during embryonic angiogenesis. Blood 114:1123–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gegonne A, Punyammalee B, Rabault B, Bosselut R, Seneca S, Crabeel M, Ghysdael J. 1992. Analysis of the DNA binding and transcriptional activation properties of the Ets1 oncoprotein. New Biol. 4:512–519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lelievre E, Lionneton F, Soncin F, Vandenbunder B. 2001. The Ets family contains transcriptional activators and repressors involved in angiogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 33:391–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tian G, Erman B, Ishii H, Gangopadhyay SS, Sen R. 1999. Transcriptional activation by ETS and leucine zipper-containing basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2946–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang C, Shapiro LH, Rivera M, Kumar A, Brindle PK. 1998. A role for CREB binding protein and p300 transcriptional coactivators in Ets-1 transactivation functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2218–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yordy JS, Muise-Helmericks RC. 2000. Signal transduction and the Ets family of transcription factors. Oncogene 19:6503–6513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baillat D, Laitem C, Leprivier G, Margerin C, Aumercier M. 2009. Ets-1 binds cooperatively to the palindromic Ets-binding sites in the p53 promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dutta D, Ray S, Vivian JL, Paul S. 2008. Activation of the VEGFR1 chromatin domain: an angiogenic signal-ETS1/HIF-2alpha regulatory axis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:25404–25413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Robinson L, Panayiotakis A, Papas TS, Kola I, Seth A. 1997. ETS target genes: identification of egr1 as a target by RNA differential display and whole genome PCR techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:7170–7175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rutter JL, Mitchell TI, Buttice G, Meyers J, Gusella JF, Ozelius LJ, Brinckerhoff CE. 1998. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the matrix metalloproteinase-1 promoter creates an Ets binding site and augments transcription. Cancer Res. 58:5321–5325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sato Y, Kanno S, Oda N, Abe M, Ito M, Shitara K, Shibuya M. 2000. Properties of two VEGF receptors, Flt-1 and KDR, in signal transduction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 902:201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Simon MP, Tournaire R, Pouyssegur J. 2008. The angiopoietin-2 gene of endothelial cells is up-regulated in hypoxia by a HIF binding site located in its first intron and by the central factors GATA-2 and Ets-1. J. Cell. Physiol. 217:809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wakiya K, Begue A, Stehelin D, Shibuya M. 1996. A cAMP response element and an Ets motif are involved in the transcriptional regulation of flt-1 tyrosine kinase (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1) gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30823–30828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Horikawa T, Sheen TS, Takeshita H, Sato H, Furukawa M, Yoshizaki T. 2001. Induction of c-Met proto-oncogene by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 and the correlation with cervical lymph node metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 159:27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murakami Y, Yamagoe S, Noguchi K, Takebe Y, Takahashi N, Uehara Y, Fukazawa H. 2006. Ets-1-dependent expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors is activated by latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus through interaction with Daxx. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28113–28121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ye FC, Blackbourn DJ, Mengel M, Xie JP, Qian LW, Greene W, Yeh IT, Graham D, Gao SJ. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus promotes angiogenesis by inducing angiopoietin-2 expression via AP-1 and Ets1. J. Virol. 81:3980–3991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xie J, Ajibade A, Ye F, Kuhne K, Gao S. 2008. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus from latency requires MEK/ERK, JNK and p38 multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Virology 371:139–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu F, Harada JN, Brown HJ, Deng H, Song MJ, Wu TT, Kato-Stankiewicz J, Nelson CG, Vieira J, Tamanoi F, Chanda SK, Sun R. 2007. Systematic identification of cellular signals reactivating Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. PLoS Pathog. 3:e44 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vart RJ, Nikitenko LL, Lagos D, Trotter MW, Cannon M, Bourboulia D, Gratrix F, Takeuchi Y, Boshoff C. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded interleukin-6 and G-protein-coupled receptor regulate angiopoietin-2 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 67:4042–4051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Godfrey A, Anderson J, Papanastasiou A, Takeuchi Y, Boshoff C. 2005. Inhibiting primary effusion lymphoma by lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA. Blood 105:2510–2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alkharsah KR, Singh VV, Bosco R, Santag S, Grundhoff A, Konrad A, Stürzl M, Wirth D, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schulz TF. 2011. Deletion of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus FLICE inhibitory protein, vFLIP, from the viral genome compromises the activation of STAT1-responsive cellular genes and spindle cell formation in endothelial cells. J. Virol. 85:10375–10388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Buggy Y, Maguire TM, McGreal G, McDermott E, Hill AD, O'Higgins N, Duffy MJ. 2004. Overexpression of the Ets-1 transcription factor in human breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 91:1308–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Katayama S, Nakayama T, Ito M, Naito S, Sekine I. 2005. Expression of the ets-1 proto-oncogene in human breast carcinoma: differential expression with histological grading and growth pattern. Histol. Histopathol. 20:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nakayama T, Ito M, Ohtsuru A, Naito S, Sekine I. 2001. Expression of the ets-1 proto-oncogene in human colorectal carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 14:415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. DiMaio TA, Gutierrez KD, Lagunoff M. 2011. Latent KSHV infection of endothelial cells induces integrin beta3 to activate angiogenic phenotypes. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002424 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Guilluy C, Zhang Z, Bhende PM, Sharek L, Wang L, Burridge K, Damania B. 2011. Latent KSHV infection increases the vascular permeability of human endothelial cells. Blood 118:5344–5354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang L, Damania B. 2008. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus confers a survival advantage to endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 68:4640–4648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wu YH, Hu TF, Chen YC, Tsai YN, Tsai YH, Cheng CC, Wang HW. 2011. The manipulation of miRNA-gene regulatory networks by KSHV induces endothelial cell motility. Blood 118:2896–2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yoshimatsu Y, Yamazaki T, Mihira H, Itoh T, Suehiro J, Yuki K, Harada K, Morikawa M, Iwata C, Minami T, Morishita Y, Kodama T, Miyazono K, Watabe T. 2011. Ets family members induce lymphangiogenesis through physical and functional interaction with Prox1. J. Cell Sci. 124:2753–2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]