Editor

Corneal nerves are known to contribute significantly to ocular surface integrity. A normal corneal innervation is required for a normal tear secretion and flow. In fact, dry eye disease is defined as a disorder of the lacrimal functional unit, an integrated system comprising the sensory and motor nerves (DEWS 2007). Corneal nerve depletion reduces tear secretion by decreasing reflex-induced lacrimal secretion and by reducing the blink rate. Moreover, corneal nerves secrete up to 17 different mediators such as Nerve Growth Factor and others which have profound effects on corneal surface homeostasis (Müller et al. 2003).

Damage to the sensory nerves in the ocular surface, particularly the cornea, is common in a number of conditions, including refractive surgery, keratoplasty and even normal aging (He et al. 2010). Corneal nerve damage often occurs in concomitance with inflammation elicited by surgery or drugs; hence it is difficult to precisely dissect the role of corneal nerves in dry eye.

We recently developed a murine model of corneal denervation (TSE, Trigeminal Stereotactic Electrolysis) where we selectively ablate the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (Ferrari et al. 2011). We used this model to test whether and to which extent selective sensory nerve ablation could induce dry eye in terms of (i) tear secretion and (ii) corneal fluorescein staining.

Eight eyes of eight C57BL/6 mice were used. Animals were examined before and 7 days after TSE. The effectiveness of the procedure was confirmed by the absence of blink reflex (Ferrari et al. 2011). At the end of the procedure a complete tarsorrhaphy was performed to minimize the effect of absent blink reflex. The animals were examined using a biomicroscope and tear production was quantified with phenol red thread test. Finally, the corneas were stained with fluorescein, and scored according to the National Eye Institute Grading System.

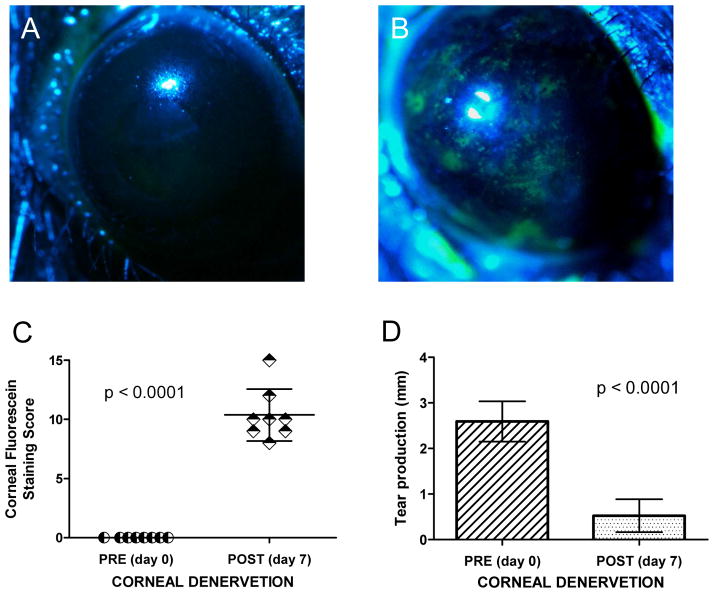

Before TSE was performed, biomicroscopy revealed a normal cornea. Corneal fluorescein staining was negative before TSE (score: 0), and phenol test was 2.59 ± 0.44 mm (mean ± SD). Corneal reflex was tested with a cotton thread and found to be present in all the eyes. Following TSE, cornea fluorescein staining score was 10.39 ± 2.20 (mean ± SD), phenol test decreased to 0.52 ± 0.36 mm (mean ± SD) and corneal reflex was absent in all the eyes (Fig. 1). After TSE, we found significant differences in both the fluorescein score (P<0.0001) and the phenol test (P<0.0001) compared to the tests at baseline before TSE (paired t-test).

Fig. 1.

Panels A, B: development of punctate keratitis following TSE-induced corneal denervation. Note the development of fluorescein positive lesions (B) which were not present before TSE treatment (A). Panel C: the amount of corneal staining was significantly increased following TSE (P<0.0001, paired t-test). Panel D: tear production, measured with the phenol red test, significantly decreased following TSE (P<0.0001, paired t-test). Vertical bars are (±) standard deviation (SD) of the mean.

In conclusion, sensory corneal denervation induces a form of dry eye in the TSE murine model. This occurred despite complete tarsorrhaphy, suggesting that reduction of the blink reflex was not responsible for this finding. Functional inhibition of corneal nerves with topical anesthesia is able to reduce tear flow up to 75% (Jordan & Baum 1980). In this model, tear production was reduced by approximately 5 times.

Our findings may be due to the reduced sensory drive from the ocular surface, which, together with a reduced trophic influence of the nerves on the ocular surface epithelium, could result in a dry eye phenotype.

We suggest that the TSE model may be useful in the study of dry eye disease, in particular as a model for the dry eye patients who also demonstrate significant “neurotrophic” disease, such as viral keratitis, diabetes, or after refractive surgery.

References

- DEWS Definition and Classification Subcommittee . The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Sucommitee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. Ocular Surf. 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Chauhan SK, Ueno H, Nallasamy N, Gandolfi S, Borges L, Dana R. A novel mouse model for neurotrophic keratopathy: trigeminal nerve stereotactic electrolysis through the brain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2532–2539. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Bazan NG, Bazan HE. Mapping the entire human corneal nerve architecture. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Baum J. Basic tear flow. Does it exist? Ophthalmology. 1980;87:920–930. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller LJ, Marfurt CF, Kruse F, Tervo TM. Corneal nerves: structure, contents and function. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:521–542. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]