Abstract

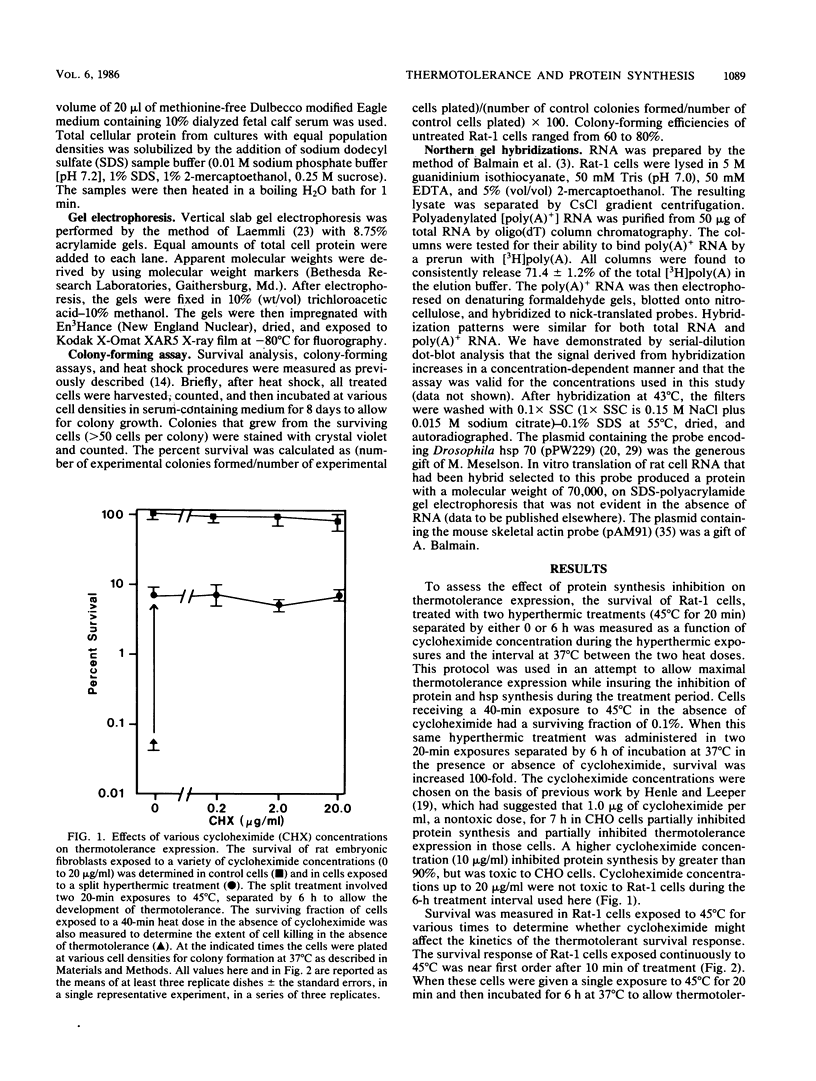

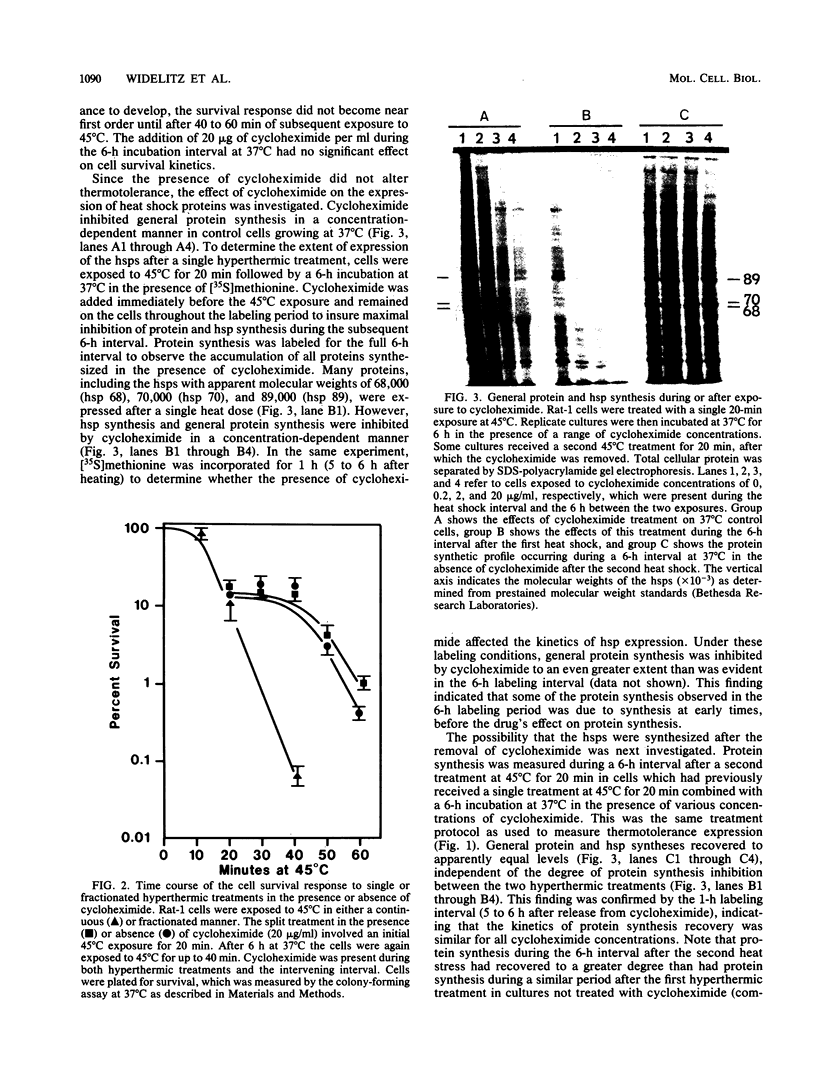

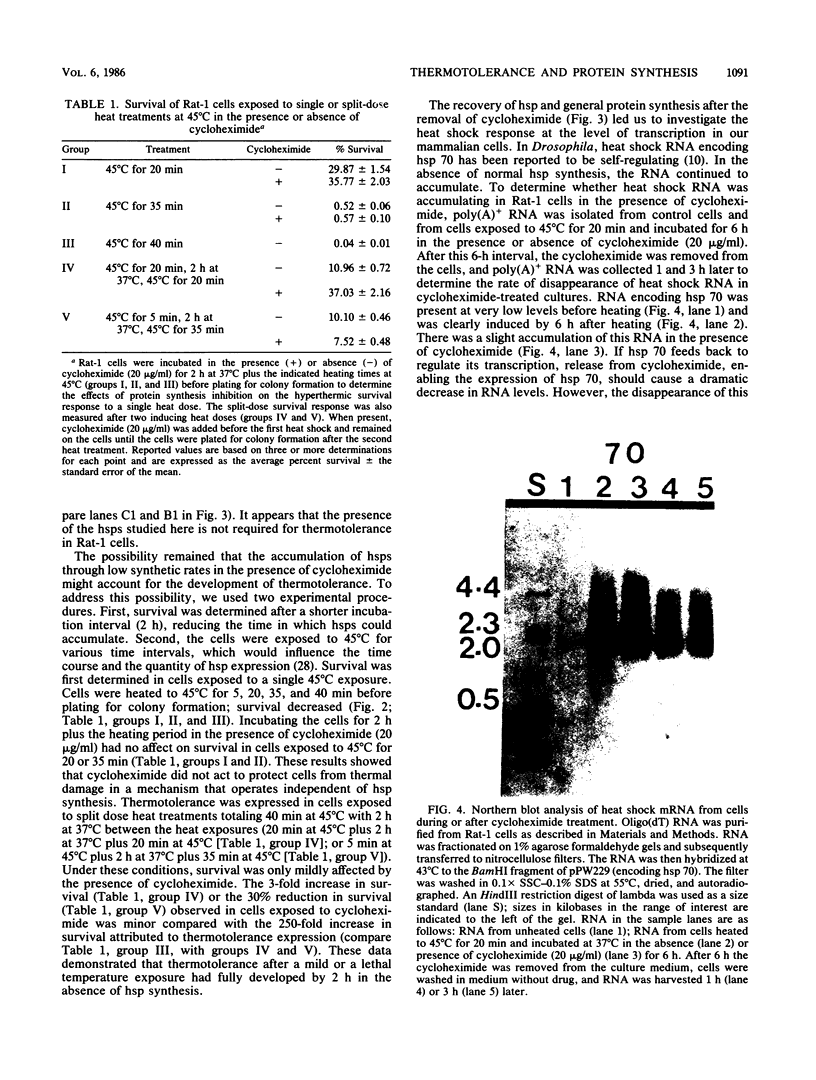

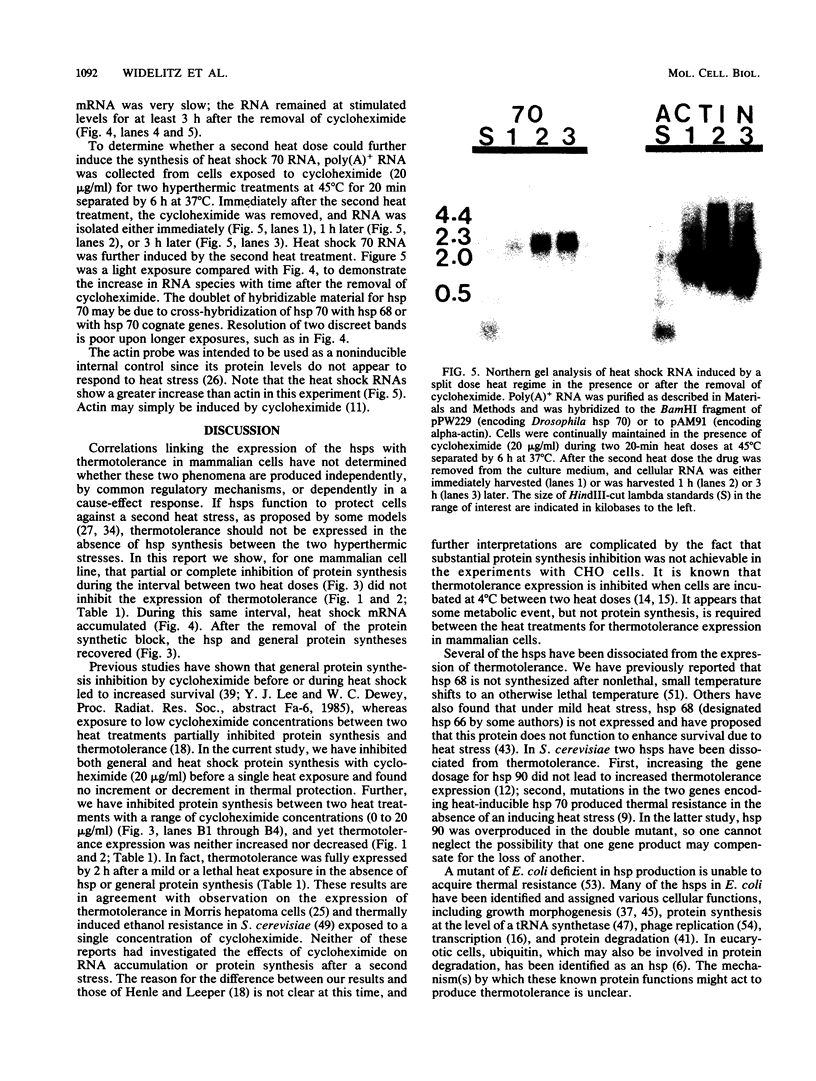

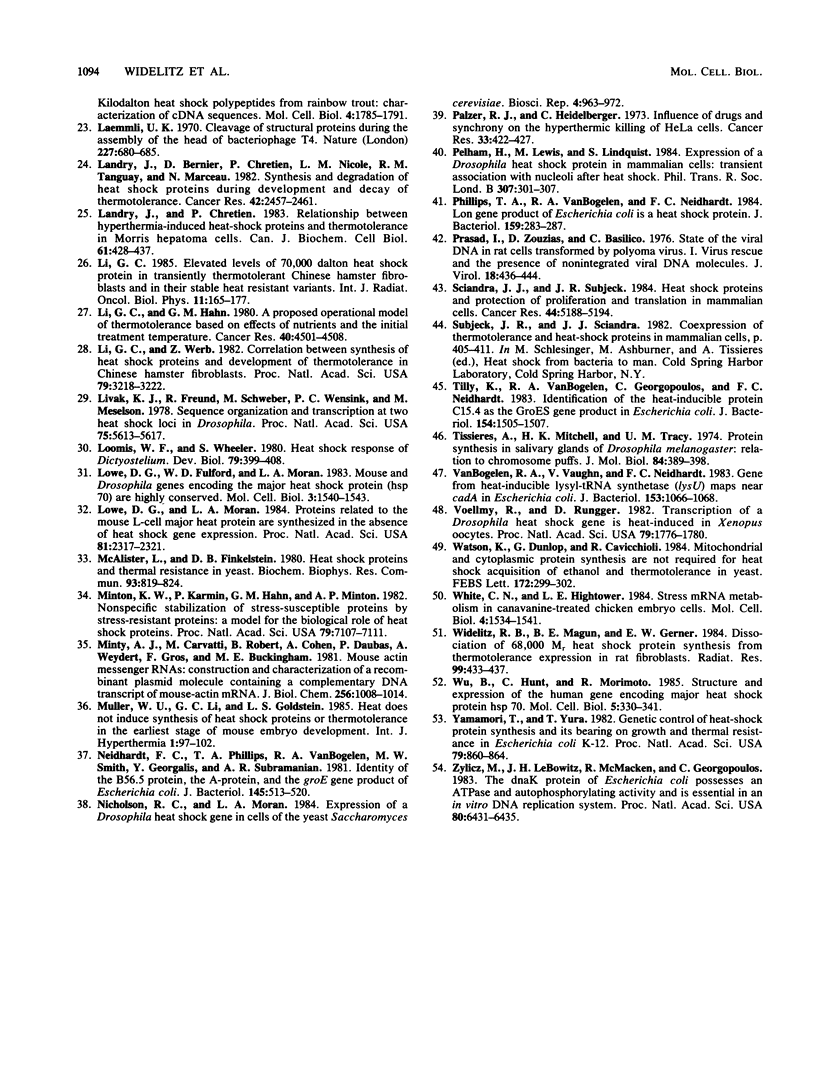

A single hyperthermic exposure can render cells transiently resistant to subsequent high temperature stresses. Treatment of rat embryonic fibroblasts with cycloheximide for 6 h after a 20-min interval at 45 degrees C inhibits protein synthesis, including heat shock protein (hsp) synthesis, and results in an accumulation of hsp 70 mRNA, but has no effect on subsequent survival responses to 45 degrees C hyperthermia. hsp 70 mRNA levels decreased within 1 h after removal of cycloheximide but then appeared to stabilize during the next 2 h (3 h after drug removal and 9 h after heat shock). hsp 70 mRNA accumulation could be further increased by a second heat shock at 45 degrees C for 20 min 6 h after the first hyperthermic exposure in cycloheximide-treated cells. Both normal protein and hsp synthesis appeared increased during the 6-h interval after hyperthermia in cultures which received two exposures to 45 degrees C for 20 min compared with those which received only one treatment. No increased hsp synthesis was observed in cultures treated with cycloheximide, even though hsp 70 mRNA levels appeared elevated. These data indicate that, although heat shock induces the accumulation of hsp 70 mRNA in both normal and thermotolerant cells, neither general protein synthesis nor hsp synthesis is required during the interval between two hyperthermic stresses for Rat-1 cells to express either thermotolerance (survival resistance) or resistance to heat shock-induced inhibition of protein synthesis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ashburner M., Bonner J. J. The induction of gene activity in drosophilia by heat shock. Cell. 1979 Jun;17(2):241–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmain A., Ramsden M., Bowden G. T., Smith J. Activation of the mouse cellular Harvey-ras gene in chemically induced benign skin papillomas. Nature. 1984 Feb 16;307(5952):658–660. doi: 10.1038/307658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaude O., Babinet C., Morange M., Jacob F. Heat shock proteins, first major products of zygotic gene activity in mouse embryo. Nature. 1983 Sep 22;305(5932):331–333. doi: 10.1038/305331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M., Pelham H. R. Expression of a Drosophila heat-shock protein in Xenopus oocytes: conserved and divergent regulatory signals. EMBO J. 1982;1(12):1583–1588. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond U., Schlesinger M. J. Ubiquitin is a heat shock protein in chicken embryo fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 May;5(5):949–956. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.5.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J. F., Ish-Horowicz D. Expression of Drosophila heat shock genes is regulated in Rat-cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982 Jul 10;10(13):3821–3830. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.13.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corces V., Pellicer A., Axel R., Meselson M. Integration, transcription, and control of a Drosophila heat shock gene in mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Nov;78(11):7038–7042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Jacobsen K. Mutations of the heat inducible 70 kilodalton genes of yeast confer temperature sensitive growth. Cell. 1984 Oct;38(3):841–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDomenico B. J., Bugaisky G. E., Lindquist S. The heat shock response is self-regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Cell. 1982 Dec;31(3 Pt 2):593–603. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder P. K., Schmidt L. J., Ono T., Getz M. J. Specific stimulation of actin gene transcription by epidermal growth factor and cycloheximide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Dec;81(23):7476–7480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein D. B., Strausberg S. Identification and expression of a cloned yeast heat shock gene. J Biol Chem. 1983 Feb 10;258(3):1908–1913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerner E. W., Boone R., Connor W. G., Hicks J. A., Boone M. L. A transient thermotolerant survival response produced by single thermal doses in HeLa cells. Cancer Res. 1976 Mar;36(3):1035–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerner E. W., Schneider M. J. Induced thermal resistance in HeLa cells. Nature. 1975 Aug 7;256(5517):500–502. doi: 10.1038/256500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila J. J., Kloc M., Bury J., Schultz G. A., Browder L. W. Acquisition of the heat-shock response and thermotolerance during early development of Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 1985 Feb;107(2):483–489. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle K. J., Leeper D. B. Interaction of hyperthermia and radiation in CHO cells: recovery kinetics. Radiat Res. 1976 Jun;66(3):505–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle K. J., Leeper D. B. Modification of the heat response and thermotolerance by cycloheximide, hydroxyurea, and lucanthone in CHO cells. Radiat Res. 1982 May;90(2):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren R., Livak K., Morimoto R., Freund R., Meselson M. Studies of cloned sequences from four Drosophila heat shock loci. Cell. 1979 Dec;18(4):1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P. M., Schlesinger M. J. Antibodies to two major chicken heat shock proteins cross-react with similar proteins in widely divergent species. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Mar;2(3):267–274. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J., Bernier D., Chrétien P., Nicole L. M., Tanguay R. M., Marceau N. Synthesis and degradation of heat shock proteins during development and decay of thermotolerance. Cancer Res. 1982 Jun;42(6):2457–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J., Chrétien P. Relationship between hyperthermia-induced heat-shock proteins and thermotolerance in Morris hepatoma cells. Can J Biochem Cell Biol. 1983 Jun;61(6):428–437. doi: 10.1139/o83-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. C. Elevated levels of 70,000 dalton heat shock protein in transiently thermotolerant Chinese hamster fibroblasts and in their stable heat resistant variants. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985 Jan;11(1):165–177. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. C., Hahn G. M. A proposed operational model of thermotolerance based on effects of nutrients and the initial treatment temperature. Cancer Res. 1980 Dec;40(12):4501–4508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. C., Werb Z. Correlation between synthesis of heat shock proteins and development of thermotolerance in Chinese hamster fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 May;79(10):3218–3222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Freund R., Schweber M., Wensink P. C., Meselson M. Sequence organization and transcription at two heat shock loci in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Nov;75(11):5613–5617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis W. F., Wheeler S. Heat shock response of Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1980 Oct;79(2):399–408. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. G., Fulford W. D., Moran L. A. Mouse and Drosophila genes encoding the major heat shock protein (hsp70) are highly conserved. Mol Cell Biol. 1983 Aug;3(8):1540–1543. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.8.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. G., Moran L. A. Proteins related to the mouse L-cell major heat shock protein are synthesized in the absence of heat shock gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Apr;81(8):2317–2321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlister L., Finkelstein D. B. Heat shock proteins and thermal resistance in yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980 Apr 14;93(3):819–824. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minton K. W., Karmin P., Hahn G. M., Minton A. P. Nonspecific stabilization of stress-susceptible proteins by stress-resistant proteins: a model for the biological role of heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Dec;79(23):7107–7111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty A. J., Caravatti M., Robert B., Cohen A., Daubas P., Weydert A., Gros F., Buckingham M. E. Mouse actin messenger RNAs. Construction and characterization of a recombinant plasmid molecule containing a complementary DNA transcript of mouse alpha-actin mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1981 Jan 25;256(2):1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller W. U., Li G. C., Goldstein L. S. Heat does not induce synthesis of heat shock proteins or thermotolerance in the earliest stage of mouse embryo development. Int J Hyperthermia. 1985 Jan-Mar;1(1):97–102. doi: 10.3109/02656738509029277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt F. C., Phillips T. A., VanBogelen R. A., Smith M. W., Georgalis Y., Subramanian A. R. Identity of the B56.5 protein, the A-protein, and the groE gene product of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981 Jan;145(1):513–520. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.513-520.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson R. C., Moran L. A. Expression of a Drosophila heat-shock gene in cells of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci Rep. 1984 Nov;4(11):963–972. doi: 10.1007/BF01116895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palzer R. J., Heidelberger C. Influence of drugs and synchrony on the hyperthermic killing of HeLa cells. Cancer Res. 1973 Feb;33(2):422–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H., Lewis M., Lindquist S. Expression of a Drosophila heat shock protein in mammalian cells: transient association with nucleoli after heat shock. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1984 Dec 4;307(1132):301–307. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1984.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T. A., VanBogelen R. A., Neidhardt F. C. lon gene product of Escherichia coli is a heat-shock protein. J Bacteriol. 1984 Jul;159(1):283–287. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.283-287.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad I., Zouzias D., Basilico C. State of the viral DNA in rat cells transformed by polyoma virus. I. Virus rescue and the presence of nonintergrated viral DNA molecules. J Virol. 1976 May;18(2):436–444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.18.2.436-444.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciandra J. J., Subjeck J. R. Heat shock proteins and protection of proliferation and translation in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1984 Nov;44(11):5188–5194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly K., VanBogelen R. A., Georgopoulos C., Neidhardt F. C. Identification of the heat-inducible protein C15.4 as the groES gene product in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jun;154(3):1505–1507. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.3.1505-1507.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissières A., Mitchell H. K., Tracy U. M. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: relation to chromosome puffs. J Mol Biol. 1974 Apr 15;84(3):389–398. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen R. A., Vaughn V., Neidhardt F. C. Gene for heat-inducible lysyl-tRNA synthetase (lysU) maps near cadA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983 Feb;153(2):1066–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.1066-1068.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voellmy R., Rungger D. Transcription of a Drosophila heat shock gene is heat-induced in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):1776–1780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson K., Dunlop G., Cavicchioli R. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic protein syntheses are not required for heat shock acquisition of ethanol and thermotolerance in yeast. FEBS Lett. 1984 Jul 9;172(2):299–302. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C. N., Hightower L. E. Stress mRNA metabolism in canavanine-treated chicken embryo cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;4(8):1534–1541. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz R. B., Magun B. E., Gerner E. W. Dissociation of 68,000 Mr heat shock protein synthesis from thermotolerance expression in rat fibroblasts. Radiat Res. 1984 Aug;99(2):433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Hunt C., Morimoto R. Structure and expression of the human gene encoding major heat shock protein HSP70. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Feb;5(2):330–341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori T., Yura T. Genetic control of heat-shock protein synthesis and its bearing on growth and thermal resistance in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Feb;79(3):860–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylicz M., LeBowitz J. H., McMacken R., Georgopoulos C. The dnaK protein of Escherichia coli possesses an ATPase and autophosphorylating activity and is essential in an in vitro DNA replication system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Nov;80(21):6431–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.21.6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]