Abstract

![]()

A variety of spirocyclic heterocycles have been constructed by a double alkylation and reductive cyclization approach utilizing α-heteroatom nitriles as trianion synthons. The method provides access to heteroatom-substituted spirocycles in a variety of ring sizes that are found in natural products and are important in pharmaceutical lead development and optimization.

Spirocyclic frameworks are important motifs found in natural products and in medicinal lead compounds. These complex structures have a well defined three-dimensional spatial arrangement that exhibit specificity of action with biological receptors and enzymes.1 Spirocycic frameworks have been the target of several synthetic methods2 aimed at the construction of structurally diverse natural and nonnatural molecules. Described herein is a general strategy for the construction of spiro-heterocycles based on a reductive cyclization process.3

Efficient construction of spirocyclic heterocycles is important in the synthesis of natural products4 and pharmaceutical targets (Figure 1).5 The assembly of carbocyclic6,7 and especially, heterocyclic8 frameworks by double alkylation of α-heteronitriles is an underdeveloped transformation. Nitrile anions are competent nucleophiles that have been applied to the formation of complex molecules using nitrile anion alkylation methodology.9 Based on the double alkylation/reductive cyclization strategy we developed for the lepadiformine alkaloids,7 we set out to extend this method to the synthesis of diverse spirocyclic heterocycles.

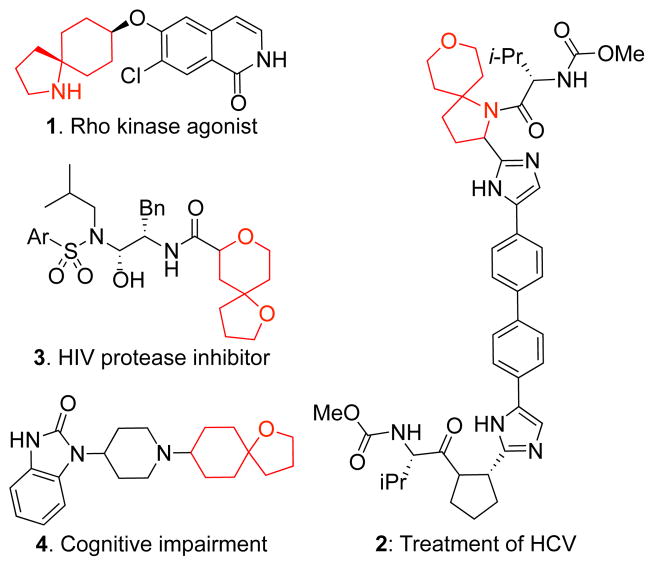

Figure 1.

Spirocyclic rings in pharmaceutical targets

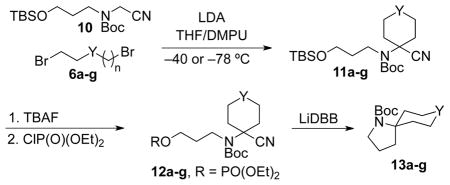

Synthesis of a variety of spirocyclic frameworks begins with double alkylation of a bis-electrophile (6) with the appropriate nitrile partner (e.g. 5). Subsequent deprotection with TBAF and phosphorylation with diethyl chlorophosphate and N-methylimidazole10 generated the cyano phosphate intermediate (8). Reductive decyanation with cyclization afforded spirotetrahydrofurans 9a–e (Table 1). The double alkylation led to good yields of cyclobutanenitrile 7a, cyclopentanenitrile 7b and cyclohexanenitrile 7c (entries 1–3). The tetrahydropyranyl adduct 7d was readily accessed from the double alkylation with 2,2′–dibromodiethylether (entry 4). Synthesis of the ketal cyclohexanenitrile 7e was achieved in moderate yield using protected 1,5-dibromopentan-3-one 6e (entry 5). The deprotection and phosphorylation steps were efficient in all cases. The reductive decyanation generates an intermediate tertiary alkyllithium reagent that cyclizes with displacement of the phosphate. The reductive cyclization in all cases proceeded with very good yield. For the volatile products 9a and 9b, the yields were estimated by GCMS analysis with an internal standard. Attempts to isolate 9a from residual THF were unsuccessful as the boiling point and polarity are too similar.

Table 1.

α-Oxonitrile double alkylation and spirocyclization

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkylation (yield) | deprotect (yield) | phosphate (yield) | reductive cyclization (yield) |

| 1 |

7a 61% |

79% | 8a 98% |

9a (98)a |

| 2 |

7b 81% |

93% | 8b 90% |

9b (94)a |

| 3 |

7c 96% |

82% | 8c 91% |

9c 89% |

| 4 |

7d 67% |

76% | 8d 84% |

9d 80% |

| 5 |

7e 51% |

85% | 8e 98% |

9e 88% |

Yield estimated by GCMS analysis using decane as an internal standard. Isolated yield of 9b was 56%.

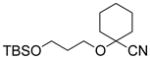

In a similar fashion, the use of aminonitrile 10 provided spiropyrrolidines 13a–g (Table 2). The cyclobutane nitrile 11a was obtained in a modest yield from the double alkylation step. The double alkylation reactions to produce unsubstituted cyclopentane 11b and cyclohexanenitrile 11c were more efficient (entries 2 and 3). Double alkylation with 1,6-dibromohexane gave a mixture of the desired cycloheptanenitrile 11g and an alkylation-elimination product in an overall 37% yield and was not investigated further. As above, the THP-aminonitrile product 11d was isolated in good yield using dielectrophile 6d. Use of protected 1,5–dibromopentan-2-one 6g (entry 7) resulted in a moderate yield due to concomitant formation of a bis-alkylated aminonitrile byproduct (19% yield). The reductive lithiation and cyclization of the N-Boc aminonitriles were all effective, but yields were more varied than in the spirotetrahydrofuran examples in Table 1. Construction of the aliphatic spiropyrrolidines proceeded in moderate to good yield irrespective of the carbocyclic ring size. Cyclization to provide symmetrically substituted spirocycle 13f also proceeded in moderate yield. In the case of 12e, the reductive cyclization proceeded in an unexpectedly low 37% yield to afford 13e. In most instances, no side products were observed or isolated in these reductive cyclization reactions. In a few cases, reduced starting material containing a terminal olefin was observed as a byproduct (≤10%), which was inseparable from the desired product by chromatography.11

Table 2.

α-Aminonitrile double alkylation and spirocyclization

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkylation (yield) | deprotect (yield) | phosphate (yield) | reductive cyclization (yield) |

| 1 |

11a 25% |

83% | 12a 86% |

13a 69% |

| 2 |

11b 63% |

91% | 12b 91% |

13b 56% |

| 3 |

11c 79% |

86% | 12c 89% |

13c 70% |

| 4 |

11g 18%a |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 5 |

11d 63% |

92% | 12d 90% |

13d 79% |

| 6 |

11e 62% |

86% | 12e 89% |

13e 37% |

| 7 |

11f 57% |

95% | 12f 61% |

13f 62% |

Cycloheptane 11g was isolated as a 1:1 mixture with an elimination byproduct.

The reductive cyclizations developed to date all use 2.2 equiv of the lithium di-tert-butylbiphenylide (LiDBB), which limits the practical scale of the reaction. We have investigated the cyclization using catalytic di-tert-butylbiphenyl (DBB) and lithium metal.12 The source of lithium metal was important with lithium powder proving more efficient than lithium wire, sheet or granules. Equation 1 shows an example on 1.23g scale using 10 mol% DBB run at 0 °C, which proceeds in good yield. Using catalytic DBB and non-cryogenic temperatures makes the cyclization step amenable to scale-up.

|

(1) |

Spiropiperidine and azepinone frameworks are also accessible by this method. Reaction of nitrile 14, which contains one more methylene unit than nitrile 10, with dibromide 6e resulted in alcohol 15 after double alkylation and deprotection. Formation of the phosphate 16a, followed by reductive cyclization generated the spiropiperidine 17 in moderate yield. The chloride 16b was prepared from 15 to test the effect of the leaving group on the spirocyclization. Reductive lithation of 16b led to the formation of both the expected spiropiperidine 17 (29%) and the unexpected spiroazepinone 18 in 43% yield. Compound 18 arose by competitive lithiation of the alkyl chloride and cyclization onto the nitrile. We have previously observed competitive lithation of alkyl chlorides with N-benzyl aminonitriles,13 but not with the more easily reduced N-Boc aminonitriles. Formation of azepinone 18 would be enhanced by using a more easily reduced halide such as bromide. Spiropiperidines are available in moderate yield using the reductive decyanation and cyclization strategy.

Spiroacetals 13f and 17 both incorporate protected secondary amines and ketones. Selective deprotection by treatment of 13f with acetic acid in THF/H2O led to removal of the 1,3-dioxolane protecting group to provide the hydrated ketone 19 in 65% yield. Acid mediated removal of the nitrogen Boc group of 18 with TFA led to a 2:1 mixture of deprotected aminoacetal and amine 20. Dilution of the crude mixture in THF and 1 M HCl provided the ketoamine 20 in 56% yield. In simple cases, acidic removal of the N–Boc group proceeded without issue (i.e. 13d to 21). Further transformations of these types of spirocycles to give valuable medicinally relevant compounds have been reported.14, 5b

We have presented a general strategy to construct spirocyclic heterocycles. The key step is a reductive lithiation and cyclization of a nitrile phosphate to form the spirocyclic pyrrolidine, piperidine or tetrahydrofuran ring. The reactions were successful with different heteroatoms and a number of ring sizes. This method will be useful in natural products synthesis and in medicinal chemistry. We are continuing to explore the selectivity and scope of this strategy.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Cyclizations to Piperidines and Azipinones

Scheme 2.

Deprotection of Spirocycles

Acknowledgments

We thank NIGMS (GM43854) for their support of this program and Vertex for a Vertex Fellowship (MAP).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rajesh SM, Perumal S, Menendez JC, Yogeeswari P, Sriram D. Med Chem Commun. 2011;2:626–630. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotha S, Deb AC, Lahiri K, Manivannan E. Synthesis. 2009;2:165–193. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Takaoka LR, Buckmelter AJ, La Cruz TE, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:528–529. doi: 10.1021/ja044642o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) La Cruz TE, Rychnovsky SD. J Org Chem. 2006;71:1068–1073. doi: 10.1021/jo052166u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) La Cruz TE, Rychnovsky SD. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2602–2611. doi: 10.1021/jo0626459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Riberio CMR, Demelo SJ, Bonin M, Quirion JC, Husson HP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:7227–7230. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Biard J-F, Guyot S, Roussakis C, Verbist J-F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2691–2694. [Google Scholar]; (b) Issa H, Tanaka J, Rachmat R, Setiawan A, Trainto A, Higa T. Mar Drugs. 2005;3:78–83. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hirasawa Y, Morita H, Kobayashi J. Org Lett. 2004;6:3389–3391. doi: 10.1021/ol048621a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Daly JW, Karle I, Myers CW, Tokuyama T, Waters JA, Witkop B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Burnell RH, Mootoo BS. Can J Chem. 1961;39:1090. [Google Scholar]; (f) Blackman AJ, Li C, Hockless DCR, Skelton BH. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:8645–8656. [Google Scholar]; (g) Blackman AJ, Li C. Aust J Chem. 1994;47:1355–1361. [Google Scholar]; (h) Blackman AJ, Li C. Aust J Chem. 1995;48:955–965. [Google Scholar]; (i) Sakamoto K, Tsujii E, Abe F, Nakanishi T, Yamashita M, Shigematsu N, Izumi S, Okuhara M. J Antibiot. 1996;49:37–44. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Shirafuji H, Tsubotani S, Ishimaru T, Harada S. WO 91 13,887 PCT Int Appl. 1991; Chem Abstr. 1992;116:39780t. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(1) Sanofi-Aventis Fr. 2009EP04393. patent WO. 2009 Jun 18;; (2) GlaxoSmithKline LLC, USA. 2010US46782. patent WO. 2010 Aug 26;; (3) Ghosh AK, Krishnan K, Walters DE, Cho W, Cho H, Koo Y, Trevino J, Holland L, Buthod J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:979–982. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (4) Glaxo Group Limited, UK. 2008EP53595. patent WO. 2008 Mar 27;; (a) The Boots Company PLC, USA. 5610161. patent US. 1997 Mar 11;; (b) Targacept, Inc., USA. 2006034089. patent WO. 2006 Mar 30;; (c) Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd USA. 5591849. patent US. 1997 Jan 7;

- 6.Guillaume D, Brum-Bousquet M, Aitken DJ, Husson H-P. Bull Soc Chim de Fran. 1994;131:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Perry MA, Morin MD, Slafer BW, Wolckenhauer SA, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9591–9593. doi: 10.1021/ja104250b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perry MA, Morin MD, Slafer BW, Rychnovsky SD. J Org Chem. 2012;77:3390–3400. doi: 10.1021/jo300161x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharpure SJ, Reddy SRB. Org Lett. 2009;11:2519–2522. doi: 10.1021/ol900721q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Fleming FF, Zhang Z. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:747–789. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Shook BC. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1–23. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soorukram D, Knochel P. Org Lett. 2004;6:2409–2411. doi: 10.1021/ol049221q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Removal of the elimination byproduct can be accomplished by dihydroxylation using OsO4, NMO in acteone/water followed by column chromatography.

- 12.(a) Guijarro D, Yus M. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:3447–3452. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramon D, Yus M. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:3585–3588. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gomez C, Lillo VJ, Yus M. Tetrahedron. 2007;93:4655–4662. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahde RJ, Rychnovsky SD. Org Lett. 2008;10:4017–4020. doi: 10.1021/ol801523r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Bonjoch J, Diaba F, Puigbó G, Peidró E, Solé D. Tetrahedron Letters. 2003;44:8387–8390. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nagumo S, Matoba A, Ishii Y, Yamaguchi S, Akutsu N, Nishijima H, Nishida A, Kawahara N. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:9871–9877. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sanofi-Aventis Fr. 2009156092. patent WO. 2009 Dec 30;; (d) Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., USA. 2011075699. patent WO. 2011 Jun 23;; (e) Rotta Research Laboratorium S.p.A., Italy. 6075033. patent US. 2000 Jun 13;

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.