Abstract

A mutation screen in Aspergillus nidulans uncovered mutations in the acdX gene that led to altered repression by acetate, but not by glucose. AcdX of A. nidulans is highly conserved with Spt8p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and since Spt8p is a component of the Spt-Ada-Gcn5 Acetyltransferase (SAGA) complex, the SAGA complex may have a role in acetate repression in A. nidulans. We used a bioinformatic approach to identify genes encoding most members of the SAGA complex in A. nidulans, and a proteomic analysis to confirm that most protein components identified indeed exist as a complex in A. nidulans. No apparent compositional differences were detected in mycelia cultured in acetate compared to glucose medium. The methods used revealed apparent differences between Yeast and A. nidulans in the deubiquitination (DUB) module of the complex, which in S. cerevisiae consists of Sgf11p, Sus1p, and Ubp8p. Although a convincing homologue of S. cerevisiae Ubp8p was identified in the A. nidulans genome, there were no apparent homologues for Sus1p and Sgf11p. In addition, when the SAGA complex was purified from A. nidulans, members of the DUB module were not co-purified with the complex, indicating that functional homologues of Sus1p and Sgf11p were not part of the complex. Thus, deubiquitination of H2B-Ub in stress conditions is likely to be regulated differently in A. nidulans compared to S. cerevisiae.

Introduction

The SAGA complex has been extensively studied in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and is highly conserved from yeast to humans [1].

In S. cerevisiae, the SAGA complex is a 1.8 MDa multiprotein complex involved in the regulation of genes that are expressed in response to stresses including metabolic starvation, DNA damage and heat, that account for approximately 10% of yeast genes [2]. Certain components of the SAGA complex bind directly to the TATA-box binding protein (TBP), and these interactions are important for the recruitment of TBP to the promoter [3]. The SAGA complex in S. cerevisiae consists of approximately 20 polypeptide subunits, which form modules within the complex [4]. One module, required for histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity, comprises Gcn5p, Ada2p, Ada3p and Sgf29p. A second module, required for TBP binding, contains both Spt3p and Spt8p. Mutations in genes encoding proteins in the third module, Spt20p, Spt7p and Ada1p, have severe phenotypes due to complete disruption of the SAGA complex, whilst mutations of Spt3p and Spt8p have milder phenotypes [5], [6]. The fourth module includes Ubp8p, a histone deubiquitinase, Sgf11p and Sus1p, which are co-dependent for the deubiquitinating activity and their interaction with the SAGA complex, and Sgf73p, which is required to maintain proper histone ubiquitination levels by anchoring the deubiquitination module to the SAGA complex [7]–[9]. SAGA also contains transcription association factors (TAFIIs), Tra1, which interacts with activators, Chd1p, which is a chromatin remodeling protein that has been shown to specifically interact with methylated lysine 4 on Histone H3 that is associated with transcriptional activity, and Sgf29p, which binds to methylated histone H3K4, this in turn facilitates histone H3 acetylation by the SAGA complex [10]–[15].

Less is known about the SAGA complex in A. nidulans. Reyes-Dominguez et al. (2008) analysed strains containing deletions in gcnE (GCN5) and adaB (ADA2), and found that nucleosome positioning and histone H3 acetylation are independent processes at the prnD-prnB bi-directional promoter [16]. In inducing-repression conditions, gcnE and adaB deletion strains showed partial derepression of the prnD-prnB transcripts, indication the possible requirement of GcnE and AdaB for repression via CreA, which was surprising as Gcn5p and Ada2p are required for transcription of Gcn5p dependent promoters in S. cerevisiae. Neither deletion affected the fully induced levels of the prnD-prnB transcripts, suggesting that induction is independent of GcnE and AdaB [16]. When A. nidulans and Streptomyces rapamycinicus interact, both exhibit a stress response. Nuetzmann and colleagues used strains containing deletions in gcnE and adaB to investigate the response to bacterial stress in these A. nidulans strains, and showed that the bacterium induces a histone modification via the SAGA complex, and the activation of a cluster of genes required for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites derived from orsellinic acid [17].

Carbon catabolite repression is a mechanism in microorganisms, which has evolved to regulate gene expression in response to their environment. In the presence of a favorable carbon source (e.g. glucose) the transcription of genes encoding enzymes required for the utilization of alternative carbon sources is repressed [18], [19].

In Aspergillus nidulans, glucose repression has been extensively studied, and repression of a large number of genes subject to carbon catabolite repression requires the transcriptional repressor CreA [20]. In A. nidulans, acetate is a repressing carbon source that leads to similar levels of CreA mediated repression as glucose [21]. The acdX gene was identified in a mutation screen in A. nidulans to identify mutations affecting acetate repression, but not glucose repression. The conservation of the amino acid sequence of AcdX of A. nidulans and the SAGA component Spt8 of S. cerevisiae initially suggested that the SAGA complex may play a role in acetate repression in A. nidulans [21].

Although some experiments on GcnE and AdaB null strains have been reported, no studies have previously been undertaken to show whether all the components of the SAGA complex are present in the A. nidulans genome, and whether the proteins form a complex in A. nidulans. We report results of bioinformatic analyses to indicate whether genes encoding the SAGA complex proteins are present in the A. nidulans genome. We followed this up using a biochemical approach, involving TAP-tag purification and western blot, to confirm which proteins are present as a physical complex in A. nidulans. Since initial studies indicated that acdX mutations affect acetate but not glucose repression [21], we also used protein purification to determine whether there are differences in protein composition of the SAGA complex in cells grown in glucose compared with acetate repressing conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics Tools

The Saccharomyces genome database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) and the Aspergillus genome database (http://www.aspgd.org/), which provide integrated biological information for the organisms, as well as tools for analysis and comparison of sequences, were used in this analysis. The Pairwise Sequence Alignment tool, EMBOSS Needle (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/), which creates an optimal global alignment of two sequences using the Needle-Wunsch algorithm, was used to align sequences.

Strains and Media

The genotypes of A. nidulans strains are shown in Table 1. Aspergillus complete and minimal media are based on those described by Cove [22]. Carbon and nitrogen sources were added aseptically to the media to the final concentrations shown for each test. Transformation of A. nidulans was based on the procedure of Tilburn et al. [23].

Table 1. Genotypes of strains used in this study.

| Pseudonym | Genotype | Derivation |

| acdXΔ;nkuAΔ | yA1;[acdX::A.f. riboB]; pyroA4 [nkuA::argB]; riboB2 | [21] |

| MYCacdX;nkuAΔ | yA1;[A.f. riboB::MYCacdX];pyroA4 [nkuA::argB]; riboB2 | [21] |

| sptCΔ; MYCacdX;nkuAΔ | yA1;[MYCacdX];pyroA4[nkuA::argB];[sptC::A.f. riboB] riboB2 | [21] |

| N −TAP sptC;MYCacdX;nkuAΔ | yA1;[MYCacdX];pyroA4[nkuA::argB];[N −TAP sptC] | This work |

Construction of N−TAPSptC Strain

To obtain a strain expressing SptC N-terminally epitope tagged with the tap tag (N−TAPSptC), a construct was made that contained N−TAP sptC. To achieve this, primers were designed to amplify N-TAP from pME2968 kindly provided by Professor Gerhard H. Braus [24]. These primers were designed to incorporate sites for the restriction enzymes NcoI and ApaI, to enable the desired vector to be obtained via a digestion/ligation approach (Table 2). Primers were also designed to amplify the vector containing sptC (pSPTC), such that the restriction sites for NcoI and ApaI were incorporated immediately after the start codon, such that upon ligation with the purified N-TAP PCR product, N-TAP would be incorporated immediately after the start codon and in frame (Table 2). The pN−TAPSPTC construct was linearized and transformed into a strain containing a deletion of sptC (sptCΔ; MYC acdX;nkuAΔ) [21]. Transformants were obtained by homologous integration as the strains used were in a nkuAΔ background [25], and detected by morphological observation.

Table 2. Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Primer sequence 5′–3′ |

| SptCfApaI | GAA GGG CCC TCG TCT GAT CGT ACT CCT |

| SptCrNcoI | GCT CCA TGG CAT ATT GCG ATT GCG AAT CTG GGA |

| N-TAPfNcoI | GCG CCA TGG GCC GTG GAC AAC AAA TTC |

| N-TAPrApaI | AGC GGG CCC ATC AAG TGC CCC GGA GGA |

Protein Purification and Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) for A. nidulans

Tandem affinity purification was performed as described in [24]. The purified proteins were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and bands were excised from the silver-stained gel manually, then washed, destained, reduced, alkylated, digested, and extracted. Vacuum concentrated samples were resuspended with 0.1% FA in 2% ACN to a total volume of 8 µl. LC-eSI-IT MS/MS was performed using an online 1100 series HPLC system (Aligent Technologies) and HCT Ultra 3D-Ion-Trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). The LC system was interfaced to the MS using an Agilent Technologies Chip Cube operating with a ProtlD-Chip-150 (II), which integrates the enriched column (Zorbax 300 SB-C18, 150 nm×75 nm), and nanospray emitter. Ionizable species were trapped and the two most intense ions were eluting at the time were fragmented by collision-induced dissociation. MS and MS/MS spectra were subjected to peak detection and de-convolution using DataAnalysis (Version 3.4, Burker Daltonics). Compound lists were exported into BioTools (Version 3.1, Burker Daltonics) then submitted to Mascot (Version 2.2).

Results and Discussion

Presence of Homologues of SAGA Complex Proteins in A. nidulans

Bioinformatic analysis was initially undertaken to indicate whether the SAGA complex components were present in the A. nidulans genome. The SAGA complex components required for structural integrity, HAT activity, TBP-binding, activator interaction, chromatin remodeling, and the TAFIIs, were all present in the A. nidulans genome (Table 3). Although potential homologues of Ubp8p and Sgf73p, which in S. cerevisiae are part of the deubiquitinating module, were identified in the A. nidulans genome, there were no convincing Sus1p and Sgf11p homologues. Accession number AN7253 and AN8685 were most similar to Sus1p and Sgf11p respectively, and using EMBOSS needle alignment, Sus1p and AN7253 were 10.4% identical, and Sgf11p and AN8685 were 8.3% identical (Table 3). The Expect (E) values of Sus1p and Sgf1p are of the order E− .02, whereas other proteins are very much lower E− .08, and it is unlikely that these are homologues of the S. cerevisiae proteins.

Table 3. The SAGA complex components present in the A. nidulans genome.

| Functional modulea | S. cerevisiae b | A. nidulans Acc #c | Similarity/Identity | E-value |

| Structural integrity | Spt20p | AN0976 (RfeE) | 22.1/13.4 | 1.0E− 08 |

| “ | Spt7p | AN4894 | 39.7/25.0 | 1.0E− 89 |

| “ | Ada1p | AN10953 | 35.1/22/7 | 2.0E− 17 |

| Hat activity | Gcn5p | AN3621 (GcnE) | 69.5/53.0 | 2.0E− 135 |

| “ | Ada2p | AN10763 (AdaB) | 57.7/41.7 | 1.0E− 106 |

| “ | Ada3p | AN0440 | 39.1/24.2 | 1.0E− 43 |

| TBP binding | Spt8p | AN4670 (AcdX) | 44.9/29.2 | 4.0E− 46 |

| “ | Spt3p | AN0719 (SptC) | 65.4/47.1 | 2.0E− 75 |

| TAFIIs | Taf5p | AN0292 | 42.0/28.2 | 8.0E− 115 |

| “ | Taf6p | AN8232 | 57.2/37.6 | 1.0E− 90 |

| “ | Taf9p | AN0794 | 35.1/24.3 | 3.0E− 30 |

| “ | Taf10p | AN0154 | 36.9/27.2 | 4.0E− 14 |

| “ | Taf12p | AN2769 | 37.3/24.1 | 1.0E− 28 |

| Deubiquitination | Sgf73p | AN11747 | 24.4/16.1 | 1.0E− 17 |

| “ | Ubp8p | AN3711 | 44.9/30.7 | 1.0E− 56 |

| “ | Sus1p | AN7253 | 21.3/10.4 | 3.8E− 02 |

| “ | Sgf11p | AN8685 | 13.8/08.3 | 9.2E− 02 |

| Interact H3K4m | Chd1p | AN1255 | 51.3/37.6 | 0.00 |

| “ | Sgf29p | AN0668 | 27.4/19.3 | 1.0E− 23 |

| Interact activators | Tra1p | AN8000 | 22.1/13.4 | 0.00 |

Functional Expression of SptC Epitope Tagged with the Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) Tag

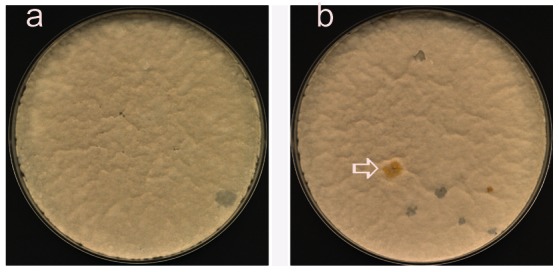

To determine that the SAGA proteins exist as a complex in A. nidulans, SptC, the homologue of Spt3p known to be a component of the SAGA complex in S. cerevisiae, was epitope tagged with the TAP tag, to allow tandem affinity purification of the complex. The N−TAP sptC fusion was integrated into the A. nidulans genome as a single copy at its native locus, in a strain containing a deletion of sptC. Since sptC mutant strains conidiate poorly giving them a white appearance [21], (Figure 1a), this allows direct identification of complementing transformants, as if N−TAPSptC is functional, all transformants should have strong, yellow conidiation. The desired transformants were obtained by homologous integration in an nkuAΔ background (Figure 1b), [25], and the presence of the N-TAP tag was confirmed (Figure S1).

Figure 1. Complementation of the sptCΔ MYC acdXnkuAΔ by pN−TAPSPTC.

sptCΔ MYC acdXnkuAΔ protoplasts plated on osmotically stabilised minimum medium, after 3 days growth at 37°C. A) No DNA control. B) Transformed with pN−TAPSPTC; arrow indicates complemented transformant.

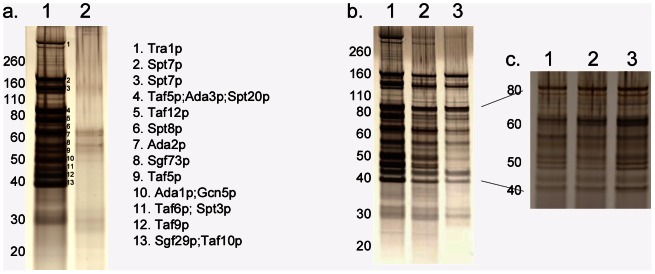

Initially, the SAGA complex was purified from strains grown in medium containing 1% glucose as the sole carbon source and 10 mM ammonium tartrate as the nitrogen source. Figure 2a shows the results of a silver-stained polyacrylamide gel, which contains the purified eluates of the experimental strain containing N−TAPSptC, and the control strain containing wildtype SptC (Figure 2a). Gel slices containing proteins from the silver-stained gel were digested using trypsin, and peptides were analyzed by LC MS analysis. The control lane, containing the MYC acdX; nkuAΔ eluate, showed typical weak background bands from TAP purification, but no SAGA subunits were detected. The experimental lane, containing the N-TAPSptC eluate, shows multiple bands, and LC MS analysis indicated that they were SAGA complex subunits. Figure 2a shows the SAGA complex subunits identified. Full details showing the complex components, A. nidulans accession numbers, predicted molecular weights, sequence coverage and the peptides identified are available in Table S1.

Figure 2. SAGA complex purification.

a) Tandem affinity purification of a strain containing SptC tagged with the TAP tag (Lane 1) and a strain with wildtype SptC (Lane 2). The gel regions that were purified are numbered, and the S. cerevisiae homologues of the SAGA complex components identified in A. nidulans by LC MS are shown on the right. b) Tandem affinity purification of the N-TAPsptC;MYCacdX;nkuAΔ strain grown in media containing either 1% glucose (Lane 1), 50 mM arabinose (Lane 2) or 50 mM sodium acetate pH 6.0 (Lane 3). LC-MS was performed for all three conditions in this experiment. c) Figure 2c shows one of a further two repeat experiments, designed specifically to determine whether the differences in staining intensity around 50KDa in lane 3 of Figure 2b were robustly repeatable, showing that the apparent differences in part b are an artifact.

SAGA Complex Protein Composition of A. nidulans in Carbon Repressing and Non-repressing Conditions

The purification was repeated using A. nidulans strains grown in medium containing 1% glucose, and was also performed in A. nidulans strains grown in media with either acetate or arabinose as the sole carbon source, to determine whether there were compositional differences of the SAGA complex between these growth conditions. LC MS analysis was performed for all growth conditions tested. Acetate was used as it has previously been shown to be a repressing carbon source in A. nidulans, and initial studies had indicated that components of the SAGA complex might have a role in acetate repression [21], and arabinose was used as the non-repressing carbon source. Figure 2b shows that there were no compositional differences for SAGA between the different carbon sources used. This result is consistent with findings that acdX mutations do not lead directly to transcriptional derepression in mycelia grown in acetate medium [21].

Similarities and Differences of the SAGA Complex in A. nidulans and S. cerevisiae

In the growth conditions tested, A. nidulans was shown to contain the majority of the SAGA complex components seen in S. cerevisiae; however, the Ubp8p, and Chd1p homologues were not detected. Published microarray evidence indicates that AN3711 (UBP8), and AN1255 (CHD1) are expressed in glucose medium and the expression does not change in ethanol medium or in response to hypoxic conditions [26], [27]. S. cerevisiae Ubp8p is a histone H2B deubiquitinating enzyme that specifically removes monoubiquitin from lysine 123 of the H2B C-terminal tail [7], [28], and has been shown to form a distinct module within the SAGA complex with Sgf11p and Sus1p, which, like Ubp8p, are not required for the structural integrity of the SAGA complex. Sgf11p is required for the Ubp8p association with the SAGA complex and therefore H2B deubiquitination [29]. Furthermore, association of Sus1p with SAGA requires Ubp8p and Sgf11p. Loss of Sus1p causes an increase in H2B ubiquitinaton and H3 methylation, to similar levels as in strains lacking Ubp8p and Sgf11p. These results indicate that all three proteins are co-dependent for their interaction with SAGA, and therefore form a distinct module within the SAGA complex [8]. In the bioinformatic analysis clear A. nidulans homologues of the Sus1p and Sgf11p proteins were not identified with any confidence. AN7253 and AN8685, the most similar proteins to Sus1p and Sgf11p respectively, were not detected in the purified complex, providing further evidence that they are not functional homologues. Since Ubp8, Sus1p and Sgf11p are co-dependent for their interaction with the SAGA complex, through Sgf73 [9], the distinct deubiquiting module containing Ubp8p present in the SAGA complex in S. cerevisiae is most probably absent in the A. nidulans complex. Supporting this conclusion, the procedures used, Tap-tag purification followed by western blot, have routinely been used in Yeast in experiments where Ubp8 and Sus1 proteins were detected as part of the SAGA complex. For example, Henry and colleagues identified Ubp8 among Ada2-Tap-tag purified proteins, showing that Ubp8 is a stable component of the transcriptionally relevant SAGA and SALSA/SLIK complexes [28]. Rodriguez-Navarro and colleagues showed that Tap-tagged Sus1 enriched all members of the SAGA complex, and vice versa Tap-tagged SAGA subunits co precipitated Sus1 [30]. Pray-Grant and others identified Ubp8 among the proteins in a highly purified yeast SLIK complex [12]. And Kohler and colleagues used recriprocal Ada2-Tap tag and Sus1Tap-tag purifications, to show Sus1, Sgf11, and Ubp8 association with SAGA [8]. Thus if deubiquiting module components were present in the SAGA complex in A. nidulans, these methods should detect them.

AN3711 (Linkage Group II) encodes the most similar protein in the A. nidulans genome to the S. cerevisiae SAGA complex component Ubp8p. A deletion was made in a nkuAΔ strain of A. nidulans [25], and was phenotypically similar to wildtype [21]. This is consistent with the situation in yeast, where a UBP8 deletion strain does not have a marked phenotype [28], due most probably to other proteins that can deubiquitinate histones [21].

Although there was a clear Chd1p homologue in the genome of A. nidulans, in the growth conditions tested, it was not detected in the SAGA complex in these analyses. In S. cerevisiae, Chd1p functions in chromatin remodeling, gene expression and transcriptional elongation [31]–[33]. In strains lacking Chd1p, there is a defect in the histone acetyltransferase activity (HAT) of SAGA on nucleosomal histones [12]. Chd1p contains two chromodomains, and of these chromodomain 2 facilitates SAGA HAT activity by interacting with methylated H3-Lys9 [12]. Transcriptionally inactive euchromatin is methylated on histone H3 at Lys 4, Lys9 and Lys 27 [34]. In S. cerevisiae, methylation of H3K4 at the GAL10 locus, is tightly regulated by the ubiquitination status of H2BK123 [35]. The SAGA complex component Ubp8p is a H2B deubiquitinating enzyme, that specifically removes monoubiquitin from H2BK123 [7]. This in turn modulates the level of methylation of H3K4, and hence alters the expression of Ubp8p-dependent genes, such as GAL10 [4], [7], [34]. It has been proposed that this methyl mark may further stabilize SAGA recruitment through Chd1p interaction [12]. The observation that the Chd1p homologue is not detected as a component of the SAGA complex in the growth conditions tested in A. nidulans could be explained by the absence of the Ubp8p homologue from the SAGA complex. It is evident that Chd1p function in S. cerevisiae is dependent upon the Upb8p function. Therefore, since the homologue of Ubp8p is not detected as a component of the SAGA complex in A. nidulans under the growth conditions tested, it is possible that the homologue of Chd1p lost its functional requirement for the SAGA complex.

Conclusions

Most components of the yeast SAGA complex were identified in the A. nidulans genome, and using a TAP-tagged version of SptC we were able to confirm that these components are in a complex in A. nidulans. In the conditions tested in this study, the homologues of Ubp8p and Chd1p were not detected as part of the SAGA complex in A. nidulans, which is a key difference between the SAGA complexes of A. nidulans and S. cerevisiae. The deubiquitinating module is present in the human SAGA complex [36]. The absence of Ubp8 and Chd1 in the complex is consistent with the absence of clear homologues of Sus1p and Sgf11p in the A. nidulans genome. In S. cerevisiae, Gcn5p HAT activity in SAGA is independent of its deubiquitinating activity [9].

Further, in was evident that there were no apparent compositional differences between acetate or glucose repressing growth conditions and non-repressing growth conditions, indicating that dynamic changes in SAGA complex composition are not important in acetate or glucose repression.

Further experimentation will confirm and determine the significance of these differences within the SAGA complex between the two organisms, and whether the proteins not identified as components of the SAGA complex in A. nidulans are present in other complexes that provide these functions. Our results clearly show that there are important differences between the deubiquitination networks of S. cerevisiae and A. nidulans. Interestingly, S. cerevisiae also lacks a clear homologue of the conserved deubiquitinating enzyme encoded by the creB gene in A. nidulans, despite clear homologues being present in insects and vertebrates [37].

Supporting Information

Confirmation of N−TAP sptC . A) Ampilfication of the sptC locus from the A. nidulans using primers S3KO1 and S3KO4 [21]. B) Amplified sptC restriction products: C:ApaI; U:undigested. As expected, a 2.4 kb band was amplified for the wild type strain and a 2.9 kb band for the transformant, as the N-TAP tag is 0.5 kb. The restriction enzyme ApaI was used to digest the amplified products. The ApaI recognition site is incorporated within the N-TAP tag; thus, only the amplified product from the transformed strain will be digested by the ApaI restriction enzyme, producing bands of 1954 bp and 946 bp. The amplified product from the wild type strain contains no ApaI site. DNA sequencing confirmed that the tag was in frame and the gene mutation free.

(DOCX)

Proteins identified in the A. nidulans SAGA complex.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Gerhard H. Braus for providing us with the TAP vectors, and Dr. Peter Hoffman and Mr James Eddes at the Adelaide Proteomics Centre.

Funding Statement

Paraskevi Georgakopolous was supported by a University of Adelaide Post-graduate Research Scholarship. The research was funded internally with School of Molecular and Biomedical Science funds, with no external sources of funding. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Liu X, Vorontchikhina M, Wang Y-L, Faiola F, Martinez E (2008) STAGA recruits mediator to the MYC oncoprotein to stimulate transcription and cell proliferation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 28: 108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee TI, Causton HC, Holstege FCP, Shen WC, Hannett N, et al. (2000) Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature 405: 701–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sermwittayawong D, Tan S (2006) SAGA binds TBP via its Spt8 subunit in competition with DNA: implications for TBP recruitment. Embo Journal 25: 3791–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker SP, Grant PA (2007) The SAGA continues: expanding the cellular role of a transcriptional co-activator complex. Oncogene 26: 5329–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant PA, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts SM, Brownell JE, et al. (1997) Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: Characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes & Development 11: 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sterner DE, Grant PA, Roberts SM, Duggan LJ, Belotserkovskaya R, et al. (1999) Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: Distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19: 86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shukla A, Stanojevic N, Duan Z, Sen P, Bhaumik SR (2006) Ubp8p, a histone deubiquitinase whose association with SAGA is mediated by Sgf11p, differentially regulates lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in vivo. Molecular and Cellular Biology 26: 3339–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koehler A, Pascual-Garcia P, Llopis A, Zapater M, Posas F, et al. (2006) The mRNA export factor Sus1 is involved in Spt/Ada/Gcn5 acetyltransferase-mediated H2B deubiquitinylation through its interaction with Ubp8 and Sgf11. Molecular Biology of the Cell 17: 4228–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee KK, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Workman JL (2009) Yeast Sgf73/Ataxin-7 serves to anchor the deubiquitination module into both SAGA and Slik(SALSA) HAT complexes. Epigenetics & Chromatin 2: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grant PA, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant MG, Steger DJ, Reese JC, et al. (1998) A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell 94: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mutiu AI, Hoke SMT, Genereaux J, Hannam C, MacKenzie K, et al. (2007) Structure/function analysis of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase domain of yeast tra1. Genetics 177: 151–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pray-Grant MG, Daniel JA, Schieltz D, Yates JR, Grant PA (2005) Chd1 chromodomain links histone H3 methylation with SAGA- and SLIK-dependent acetylation. Nature 433: 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMahon SJ, Pray-Grant MG, Schieltz D, Yates JR, Grant PA (2005) Polyglutamine-expanded spinocerebellar ataxia-7 protein disrupts normal SAGA and SLIK histone acetyltransferase activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102: 8478–8482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bian C, Xu C, Ruan J, Lee KK, Burke TL, et al. (2011) Sgf29 binds histone H3K4me2/3 and is required for SAGA complex recruitment and histone H3 acetylation. Embo Journal 30: 2829–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grant PA, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant MG, Yates JR, Workman JL (1998) The ATM-related cofactor Tra1 is a component of the purified SAGA complex. Molecular Cell 2: 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reyes-Dominguez Y, Narendja F, Berger H, Gallmetzer A, Fernandez-Martin R, et al. (2008) Nucleosome positioning and histone H3 acetylation are independent processes in the Aspergillus nidulans prnD-prnB bidirectional promoter. Eukaryotic Cell 7: 656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nuetzmann H-W, Reyes-Dominguez Y, Scherlach K, Schroeckh V, Horn F, et al. (2011) Bacteria-induced natural product formation in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans requires Saga/Ada-mediated histone acetylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 14282–14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gancedo JM (1998) Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 62: 334–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelly JM (2004) The regulation of carbon metabolism in filamentous fungi. Biochemistry and molecular biology, 2nd Edition Volume 3: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dowzer CEA, Kelly JM (1991) Analysis of the creA gene, a regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans . Molecular and Cellular Biology 11: 5701–5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Georgakopoulos P, Lockington RA, Kelly JM (2012) SAGA Complex Components and Acetate Repression in Aspergillus nidulans . G3 (Bethesda, Md) 2: 1357–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cove DJ (1966) Induction and repression of nitrate reductase in fungus Aspergillus nidulans . Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 113: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tilburn J, Scazzocchio C, Taylor GG, Zabickyzissman JH, Lockington RA, et al. (1983) Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans . Gene 26: 205–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Busch S, Schwier EU, Nahlik K, Bayram O, Helmstaedt K, et al. (2007) An eight-subunit COP9 signalosome with an intact JAMM motif is required for fungal fruit body formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 8089–8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nayak T, Szewczyk E, Oakley CE, Osmani A, Ukil L, et al. (2006) A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans . Genetics 172: 1557–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David H, Hofmann G, Oliveira AP, Jarmer H, Nielsen J (2006) Metabolic network driven analysis of genome-wide transcription data from Aspergillus nidulans. Genome Biology 7: R 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27. Masuo S, Terabayashi Y, Shimizu M, Fujii T, Kitazume T, et al. (2010) Global gene expression analysis of Aspergillus nidulans reveals metabolic shift and transcription suppression under hypoxia. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 284: 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Henry KW, Wyce A, Lo WS, Duggan LJ, Emre NCT, et al. (2003) Transcriptional activation via sequential histone H2B ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation, mediated by SAGA-associated Ubp8. Genes & Development 17: 2648–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ingvarsdottir K, Krogan NJ, Emre NCT, Wyce A, Thompson NJ, et al. (2005) H2B ubiquitin protease Ubp8 and Sgf11 constitute a discrete functional module within the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA complex. Molecular and Cellular Biology 25: 1162–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tran HG, Steger DJ, Iyer VR, Johnson AD (2000) The chrome domain protein Chd1p from budding yeast is an ATP-dependent chromatin-modifying factor. Embo Journal 19: 2323–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krogan NJ, Kim M, Ahn SH, Zhong GQ, Kobor MS, et al. (2002) RNA polymerase II elongation factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a targeted proteomnics approach. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22: 6979–6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simic R, Lindstrom DL, Tran HG, Roinick KL, Costa PJ, et al. (2003) Chromatin remodeling protein Chd1 interacts with transcription elongation factors and localizes to transcribed genes. Embo Journal 22: 1846–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strahl BD, Allis CD (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Daniel JA, Torok MS, Sun ZW, Schieltz D, Allis CD, et al. (2004) Deubiquitination of histone H2B by a yeast acetyltransferase complex regulates transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry 279: 1867–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lang G, Bonnet J, Umlauf D, Karmodiya K, Koffler J, et al. (2011) The Tightly Controlled Deubiquitination Activity of the Human SAGA Complex Differentially Modifies Distinct Gene Regulatory Elements. Molecular and Cellular Biology 31: 3734–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lockington RA, Kelly JM (2001) Carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans involves deubiquitination. Molecular Microbiology 40: 1311–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Malavazi I, Savoldi M, Zingaretti Di Mauro SM, Martins Menck CF, Harris SD, et al. (2006) Transcriptome analysis of Aspergillus nidulans exposed to camptothecin-induced DNA damage. Eukaryotic Cell 5: 1688–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confirmation of N−TAP sptC . A) Ampilfication of the sptC locus from the A. nidulans using primers S3KO1 and S3KO4 [21]. B) Amplified sptC restriction products: C:ApaI; U:undigested. As expected, a 2.4 kb band was amplified for the wild type strain and a 2.9 kb band for the transformant, as the N-TAP tag is 0.5 kb. The restriction enzyme ApaI was used to digest the amplified products. The ApaI recognition site is incorporated within the N-TAP tag; thus, only the amplified product from the transformed strain will be digested by the ApaI restriction enzyme, producing bands of 1954 bp and 946 bp. The amplified product from the wild type strain contains no ApaI site. DNA sequencing confirmed that the tag was in frame and the gene mutation free.

(DOCX)

Proteins identified in the A. nidulans SAGA complex.

(DOCX)