Abstract

Introduction

We present an uncommon and yet interesting congenital anomaly and discuss the difficulties with diagnosis and controversies in management. C1 arch deficiency is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of neck pain in children.

Material and methods

A 12-year-old girl presented initially with a loud clicking emanating from the cervical spine during nappy changes in early childhood. Subsequent investigation by way of CT and MRI revealed her to have a deficient posterior arch of the C1 vertebra, and due to persistent and painful clicking she was placed into a cervical brace, which was worn for approximately 1 year. At age 12, her clicking had all but completely resolved but she continued to complain of minor neck pain. She is advised to avoid contact sports and her parents are instructed to observe any new worrying symptoms.

Conclusion

No definitive guidelines exist for the management of this congenital anomaly. Indications for surgical intervention prior to any neurological disturbance are unclear, and restricting a child from partaking in healthy activity may not be necessary. We discuss the anomaly and identified management strategies as reported in the literature so far.

Keywords: C1 vertebra, Congenital anomaly, Atlas aplasia

Case presentation

We present the case of an 18-month girl who presented to us with a loud clicking and associated discomfort emanating from the cervical spine, particularly during nappy changes. Symptoms also occurred with most other activities. She was investigated by way of plain radiograph, CT scan and MRI scan. All of the above confirmed a defect in the posterior arch of the C1 vertebra. Due to the painful clicking, at age 7 she was immobilized in a cervical collar for a period of approximately one year. This had led to almost complete cessation of the clicking sensation experienced but she is left with persistent, though minor, neck pain. In addition to bracing, she has also been advised to refrain from partaking in sporting activity, for fear of damage to the spinal cord. Neurological examination has been normal throughout childhood and continues to be so.

Diagnostic imaging

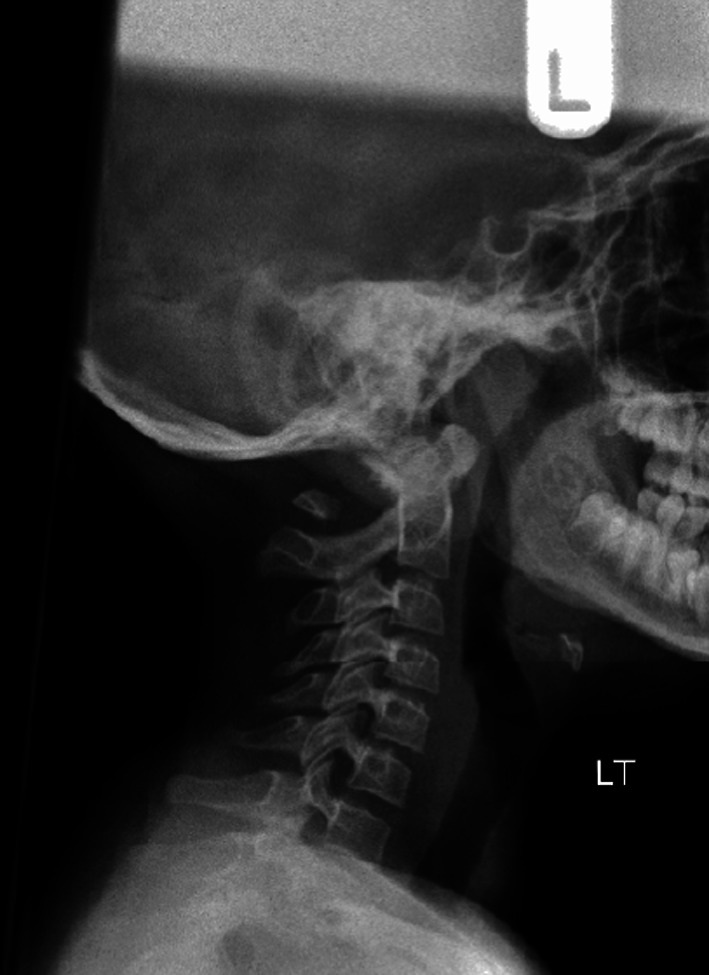

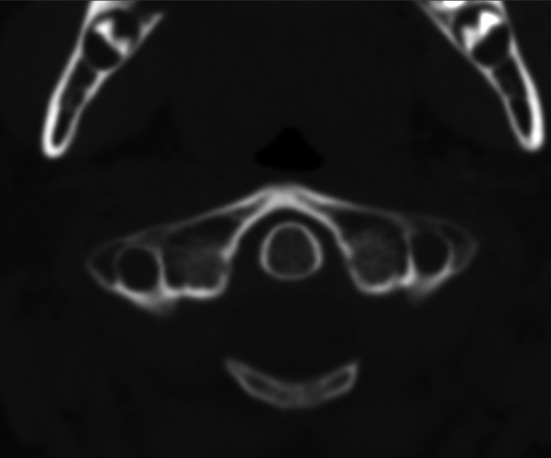

Plain lateral X-rays of the cervical spine showed absence of the posterior arch of atlas but a posterior tubercle was present (Fig. 1). CT identified a bilateral defect with a remaining posterior tubercle, isolated from any other bony contact (Figs. 2, 3). Spinal MRI revealed no associated anomalies or cord pathology.

Fig. 1.

Lateral plain X-ray showing the gap between the posterior and anterior tubercles of C1

Fig. 2.

CT axial view demonstrating bilateral clefts in the posterior arch of the C1 vertebra (Currarino Type C)

Fig. 3.

CT reconstruction view demonstrating bilateral clefts in the posterior arch of the C1 vertebra (Currarino Type C)

Historical review

Incidence

The reported incidence in a large study of 1,613 autopsies with regards to the presence of congenital aplasia in the C1 vertebra is approximately 4 % for the posterior arch and 0.1 % for the anterior arch. This anomaly is predominantly seen in children and women in their second and third decade of life [1].

Plaut, Lawrence and Anderson first published an article about a developmental abnormality of C1 in 1937. A total of 41 articles have been published about posterior defects of C1 in the literature so far [2].

C1 development and pathology

Three primary ossification centers have been described in the C1 vertebra: anterior centre, which forms the anterior tubercle; and two lateral centers, which form the lateral masses and the posterior arch. In 2 % of the population, a fourth center forms the posterior tubercle.

At the seventh intrauterine week, the lateral centers extend dorsally to form the posterior arch. At birth, the posterior arches are nearly fused except for a few millimeters of cartilage, with union occurring by the age of 4–9. The anterior center unites with the lateral centers at 5–9 years of age.

Defects of the posterior arch are thought to develop because of a failure of local chondrogenesis rather than subsequent ossification. Autopsies and intraoperative findings have supported the presence of connective tissue bridging the bony defect [3].

Types and classification

C1 posterior arch anomalies are either median clefts or hypoplasia. Hypoplasia with stenosis and a bifid posterior arch have also been reported in children. Devi et al. [4] described five children, all of whom presented with myelopathic features due to the inturned two halves of the arch.

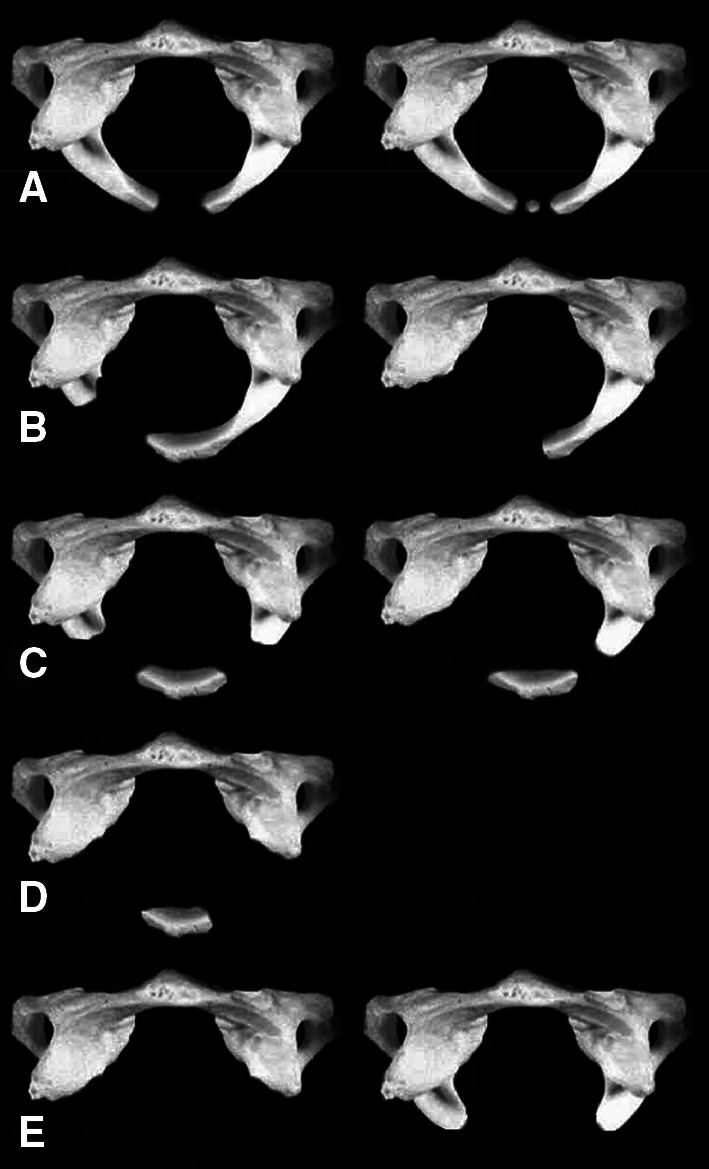

Currarino et al. [5] developed a classification system, Types (A–E), for congenital defects of the posterior arch of C1 (Fig. 4; Table 1). Over 90 % of defects are Type A. They estimated that 0.69 % of the general population harbor Types B–E. Patients with Types C and D have a free-floating posterior tubercle at the apex of the arch. It is hypothesized that to form this anomaly, the patient has both an error of chondrification as well as the rare fourth ossification center.

Fig. 4.

Autopsies showing the different C1 arch deficiencies according to Currarino classification (from [5])

Table 1.

Five different C1 arch deficiencies according to Currarino classification

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| A | Failure of posterior midline fusion of the two hemi-arches |

| B | Unilateral cleft |

| C | Bilateral cleft |

| D | Absence of the posterior arch with persistent posterior tubercle |

| E | Absence of the entire arch including posterior tubercle |

Differential diagnosis

There are certain clinical conditions that should be differentiated from C1 arch defects. Any neoplastic lytic spinal pathology (angiomas, angiosarcomas, multiple myeloma and lymphoma), osteolysis (essential, hereditary, inflammatory, rheumatoid and endocrine—hyperparathyroidism) and bone disappearing disease (Gorham’s disease) should all be considered.

Complications

The most dangerous complication in this congenital defect is spinal cord compression, which is encountered in types C and D where the posterior tubercle is present.

Inward buckling of the posterior tubercle with its attached loose fibrous tissue and the attached ligaments are the cause of cervical myelopathy while flexing and extending the neck. This was first reported by Richardson et al. [6] in 1975.

They theorized that the isolated posterior fragment moved anteriorly and traumatized the dorsal spinal cord with extension (Fig. 5). However, they could not demonstrate this on flexion–extension films.

Fig. 5.

Schematic demonstration of spinal cord compression by inward buckling of the loose C1 posterior tubercle (from [6])

Sharma et al. [7] were the first to document true inward movement of the bony tubercle with neck extension using dynamic cervical spine radiographs. This was also confirmed by MRI signal abnormality.

Most of the reported cases of C1 deficiency did in fact develop cervical myelopathy at some stage of their follow-up or indeed presented with it [3, 8−10].

Atlantoaxial instability is another complication that has been reported by Schulze et al. [11] in a case of congenital C1 posterior arch anomaly. They noticed an increase in the atlantodental interspace (on dynamic views), which was not clinically significant and their patient was not felt to warrant surgical interference.

Treatment

Non-operative management of our patient was advocated as here were no incapacitating symptoms and no evidence of any cord changes or neurological deficit. Our patient is kept under regular follow-up; however, in case neurological symptoms or signs should develop in the future. Dynamic cervical X-rays are routinely performed for assessment of atlantoaxial stability as well as posterior tubercle mobility.

The literature provides no clear recommendation for the management of C1 congenital anomalies. We have chosen to restrict our patient from significant physical activity, which may potentially cause serious harm in case of injury. On the other hand, such restriction could theoretically affect child development adversely, from a physical fitness, emotional and social point-of-view. Undoubtedly, there will be other children with similar pathology, albeit undiagnosed, who are not restricted and are unlikely to come to serious harm.

The alternative option would be a surgical fusion. No clear indication exists for such surgical intervention, however, save for established myelopathy, and those kept under close observation also present us with difficult decision making in terms of proceeding to surgery—how much movement on dynamic cervical spine X-rays warrants surgical intervention?

Key points

C1 vertebral deficiencies are an uncommon congenital anomaly. The diagnosis should be considered in cases of neck pain and/or clicking.

X-rays, CT and MRI images are the mainstay for diagnosis of this lesion and its potential complications.

Patient and parent education for avoiding any vigorous neck movements during daily activity and exercise should/could be advocated, particularly in Type C and D anomalies.

Close clinical and radiological follow-up are crucial for eliciting any findings which may necessitate surgical intervention.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Switchboard: 0115 924 9924 extension 61013/Bev Beeson—(Secretary to Mr. Hossein Mehdian).

Contributor Information

Mahmoud Mohamed Elmalky, Phone: +44-0-502462393, Email: mah_elmalky@yahoo.com, Email: elmalky.mahmoud@nuh.nhs.

Hossein Mehdian, Phone: +11-59-249924.

References

- 1.Pasku D, Katonis P, Karantanas A, Hadjipavlou A. Congenital posterior atlas defect associated with anterior rachischisis and early cervical degenerative disc disease: A case study and review of the literature. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(2):282–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabuncuogl H, Ozdogan S, Karadag D, Kaynak ET. Congenital Hypoplasia of the Posterior Arch of the Atlas: Case Report and Extensive Review of the Literature. Turkish Neurosurgery. 2011;21(1):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klimo P, Jr, Blumenthal DT, Couldwell WT. Congenital Partial Aplasia of the Posterior Arch of the Atlas Causing Myelopathy: Case Report and Review of the Literature. SPINE. 2003;28(12):E224–E228. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065492.85852.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devi BI, Shenoy SN, Panigrahi MK, et al. Anomaly of arch of atlas—a rare cause of symptomatic canal stenosis in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;26:214–218. doi: 10.1159/000121194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currarino G, Rollins N, Diehl JT. Congenital defects of the posterior arch of the atlas: A report of seven cases including an affected mother and son. AJNR Am Neuroradiology. 1994;15:249–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson EG, Boone SC, Reid RL. Intermittent quadriparesis associated with a congenital anomaly of the posterior arch of the atlas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:853–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma A, Gaikwad SB, Deol PS, et al. Partial aplasia of the posterior arch of the atlas with an isolated posterior arch remnant: findings in three cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1167–1171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikawa K, Ludwig SC, Colón RJ, Fujimoto Y, Heller JG. Cervical Myelopathy and Congenital Stenosis From Hypoplasia of the Atlas: Report of Three Cases and Literature Review. Spine. 2001;26(5):E80–E86. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan N, Marras C, Midha R, Rowed D. Cervical myelopathy caused by hypoplasia of the atlas: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(3):629–633. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199809000-00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urasaki E, Yasukouchi H, Yokota A. Atlas hypoplasia manifesting as myelopathy in a child: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001;41(3):160–162. doi: 10.2176/nmc.41.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulze PJ, Buurman R. Absence of the posterior arch of the atlas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;134:178–180. doi: 10.2214/ajr.134.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]