Abstract

Background

With cerebral palsy (CP), an equinus deformity may lead to genu recurvatum. Botulinum toxin A (BtA) injection into the calf muscles is a well-accepted treatment for dynamic equinus deformity.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to determine whether BtA injections into the calf muscles to decrease equinus would decrease coexisting genu recurvatum in children with diplegic CP.

Methods

In a retrospective study, 13 children (mean age, 5 years) with spastic diplegic CP showing equinus and coexisting primary genu recurvatum, who were treated with BtA injections into the calf muscles, were included. Evaluations were done before and 6 and 18 weeks after intervention using three-dimensional gait analysis and clinical examinations according to a standardized protocol. Basic statistical analyses (power analysis, ANOVA) were performed to compare genu recurvatum before treatment and at 6 and 18 weeks after injection with BtA.

Results

During stance phase, maximum ankle dorsiflexion was increased substantially from −3.0° ± 14.3° before to 6.2° ± 14.2° 6 weeks after the injections. Despite this, with the numbers available, the amount of recurvatum in stance did not improve with treatment at either 6 or 18 weeks. There was significant improvement of knee hyperextension during stance phase of 6.2° between baseline and 18 weeks after BtA injection, but a genu recurvatum was still present in most patients.

Conclusions

Despite improvement of ankle dorsiflexion after injection with BtA, genu recurvatum did not show relevant improvement at 6 or 18 weeks after injection with the numbers available. Because knee hyperextension remained in most patients, other factors leading to genu recurvatum should be taken into consideration. In addition, a botulinum toxin-induced weakness of the gastrocnemius may explain why recurvatum gait was not significantly reduced.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Equinus deformity is the most frequently observed deformity in patients with spastic cerebral palsy (CP) [5, 32]. Several factors may lead to equinus of which spasticity of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles is commonly seen [7, 18, 21]. Various methods for treatment of equinus have been described [15, 20, 23, 29, 31, 33]. In cases of a dynamic equinus, injection of botulinum toxin A (BtA) into the calf muscles is a widely accepted treatment and commonly combined with physiotherapy and/or orthotic treatment [8, 10]. Although the treatment with BtA injections in adults with CP is controversial [17], in children with CP, several studies report improvement of ankle dorsiflexion in passive ROM [12, 14] and as measured by gait analysis [29], lasting approximately 3 to 6 months [6, 29]. The improvements are seen especially in dynamic ankle kinematics [9, 29].

Genu recurvatum gait often is seen in patients with CP with equinus gait [4, 22, 24, 28]. Like crouch or stiff gait, there are several factors influencing the development of recurvatum gait, but detailed analysis of the underlying factors has not provided us with comprehensive answers [28, 30, 34]. The plantar flexion–knee extension couple (PFKE couple) is a well-accepted mechanism explaining the influence of equinus deformity on knee extension in the stance phase. A correlation between ankle plantar flexion and knee extension during stance phase has been described [2]. Considering those findings, shortening of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, as may occur when spasticity is present, may lead to equinus and genu recurvatum [1, 24, 30]. Consequently, a reduction of this shortening by BtA might attenuate the knee hyperextension. However, Baddar et al. [2] reported no increase of knee flexion in early or midstance phase after gastrocsoleus recession. Therefore, the influence of equinus on the development of genu recurvatum is not fully understood.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether BtA injections into the calf muscles to decrease equinus would decrease coexisting genu recurvatum by decreasing knee hyperextension during stance phase in children with diplegic CP. An additional objective was to determine whether the injections led to improvement of ankle dorsiflexion in the clinical examination and in the kinematics of the motion analysis.

Patients and Methods

In this retrospective study, we included 13 children (five females, eight males) with spastic diplegic CP. Before the injection, the mean age of the patients was 5 years. After the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, the patients were selected from our motion laboratory database according to specific inclusion criteria. We included children (range, 2–7 years) with diplegic CP showing equinus, a toe-walking pattern, and coexisting genu recurvatum. Additional preconditions for inclusion were the ability to ambulate independently (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] Levels I–II) and the presence of a primary genu recurvatum. Primary genu recurvatum was defined as knee hyperextension greater than 2° during stance phase without having had any kind of prior surgery or BtA intervention of the lower extremity. All children included in this study had a full or partial dynamic equinus foot. We included patients if they had a complete flexible equinus (toe walking but fully correctable ankle in clinical examination) or a partially dynamic equinus (toe walking and only partially correctable in clinical examination but at least to neutral position). Any patient with fixed equinus (not correctable to neutral ankle position) was excluded from this study as BtA injections are not indicated for fixed equinus deformities and therefore calf muscle lengthening is performed in those patients at our institution. Four patients had a unilateral genu recurvatum before intervention. Therefore, we excluded four limbs from the study and 22 limbs of 13 patients were analyzed.

The children were examined by three-dimensional (3-D) gait analysis and clinical examination before BtA injections and at 6 and 18 weeks after BtA injections, according to a standardized protocol. For 3-D gait analysis, we used a 120-Hertz, nine-camera system (Vicon-M-series; Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK). Skin-mounted markers were applied to bony landmarks and kinematics were evaluated according to the protocol of Kadaba et al. [11]. During the motion analysis and clinical examination the patients walked barefoot without any casts or orthoses.

The injections were performed by our pediatric orthopaedic surgery staff. Injections were given into the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, depending on Silfverskiöld’s test (ankle dorsiflexion with the knee in 0° extension and in 90° flexion), which was performed to determine if the soleus muscle participated in the equinus deformity. In all cases, an injection into the gastrocnemius muscle was done. Eighteen limbs (10 patients) received an injection into the soleus muscle as well. We injected BtA using a modification of the approach described by Cosgrove and Graham [6]. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles were injected twice, split into a medial and a lateral injection. Therefore, a reference line between the medial and lateral femoral condyles was drawn down to a point midway between the medial and lateral malleolus. The injections were applied 1 cm from that line into the proximal part of the calf. Dysport (Ipsen Biopharm Ltd, Wrexham, UK) was injected in 19 cases and Botox (Allergan Inc, Irvine, CA, USA) was used in three cases under aseptic conditions. We determined the administered dose according to an in-house, standardized, and weight-based protocol (Table 1). Dysport and Botox are approved by the FDA.

Table 1.

BtA use

| Location of injection | Number of limbs | Drug used | Mean units BtA/kg | SD | Mean units BtA | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastronemius muscle | 19 | Dysport | 9.2 | 3.9 | 159.4 | 75.0 |

| 3 | Botox | 1.0 | < 0.1 | 17.9 | 0.7 | |

| Soleus muscle | 15 | Dysport | 5.2 | 1.5 | 87.8 | 32.3 |

| 3 | Botox | 1.0 | < 0.1 | 17.9 | 0.7 |

BtA = botulinum toxin.

In this retrospective study five of the children received a multilevel BtA injection. In nine limbs an additional injection was given into the hamstrings. Furthermore seven limbs received an injection into the rectus femoris muscle.

We used basic statistics for data evaluation. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and describe the basic features of our data. Only one limb of each patient was chosen for further analysis as both limbs of one patient cannot be seen as independent. In patients with unilateral genu recurvatum, the affected limb was included (n = 4). In patients with bilateral genu recurvatum (n = 9), one randomized limb was chosen for analysis. To show presurgical and postsurgical effects and differences among the examinations, we used an ANOVA, Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05). Post hoc calculations were done to calculate the power of statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was done using PASW® Statistics 18 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

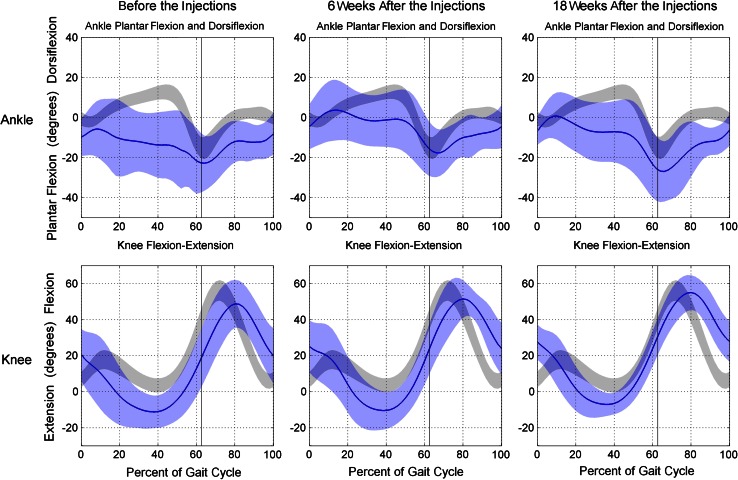

With the numbers available, there was a significant improvement in recurvatum observed at 18 weeks after the BtA injection into the calf musculature, but the patients had a mean knee hyperextension of 6.2°. The minimum knee flexion was −12.4° (SD, 9.4°) before injection; −10.2° (SD, 11.4°; p > 0.05) at 6 weeks, and −6.2° (SD 6.0°; p < 0.05) at 18 weeks (Fig. 1). Treatment with BtA resulted in significant improvement of maximum ankle dorsiflexion during stance phase at 6 weeks (maximum ankle dorsiflexion before treatment was −3.0°, SD, 14.3°; at 6 weeks, maximum ankle dorsiflexion was 6.2°, SD, 14.2°; p < 0.05). During the whole gait cycle (stance plus swing phase), with the numbers available there was a trend toward improvement in dorsiflexion at 6 weeks (before the injections, maximum ankle dorsiflexion was −1.9°, SD, 13.7°; six weeks after the injections, maximum ankle dorsiflexion was 7.2°, SD, 10.7°; p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed at 18 weeks with the numbers available (Table 2), and, as mentioned, the improvements in equinus did not result in relevant improvement of knee hyperextension with the numbers available.

Fig. 1.

The kinematics of the 22 limbs before and 6 and 18 weeks after botulinum toxin A injections are shown.

Table 2.

Knee kinematics before and 6 and 18 weeks after BtA injection

| Kinematics | Before injections | 6 weeks after injections | 18 weeks after injections | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum angle | SD | Maximum angle | SD | Maximum angle | SD | |

| Ankle dorsiflexion in stance phase | −3.0° | 14.3° | 6.2°* | 14.2° | 4.5° | 10.4° |

| Ankle dorsiflexion during gait cycle | −1.9° | 13.7° | 7.2°* | 10.7° | 4.8° | 9.8° |

| Knee recurvatum during midstance | −12.4° | 9.4° | −10.2° | 11.4° | −6.2° | 6.0° |

BtA = botulinum toxin; * significant difference (p < 0.05 in t-test) compared with the values before injection.

None of the patients showed an equinus deformity greater than 20° (measured in 0° Silfverskiold’s test before and after injection). Eighteen weeks after the BtA injection, there was significant improvement in ankle dorsiflexion detected by the 0° Silfverskiold test (Table 3). Furthermore, there was a significant difference concerning ankle dorsiflexion measured at 0°, whereas there was no significant improvement at 90° at both examinations, indicating involvement of the gastrocnemius muscle (Table 3). A post hoc power calculation showed a value of 0.96.

Table 3.

Ankle dorsiflexion with Silfverskiold’s test

| Parameter | 0° test | 90° test |

|---|---|---|

| Ankle dorsiflexion before injections | −5° (SD, 13.4°) | 7.5° (SD, 7.7°) |

| Ankle dorsiflexion 6 weeks after injections | 2.7° (SD, 13.1°) | 12.0° (SD, 7.8°) |

| p value | 0.037 | 0.070 |

Discussion

According to Sutherland and Davids [27] genu recurvatum is a relevant gait disorder in patients with CP. Equinus is assumed to be one of the leading factors in the development of recurvatum gait [24, 28, 30]. Furthermore, the mechanism of the PFKE couple, which is relevantly influenced by equinus deformity, is suspected to enhance knee extension [2]. Therefore, weakening of the calf muscles may reduce a coexisting genu recurvatum [2]. Therefore the purpose of our study was to investigate the influence of an attenuation of the calf muscles by BtA injections on recurvatum gait. Analyzing the kinematic data of the motion capture we detected a significant (p < 0.05) improvement of 9.1° in maximum ankle dorsiflexion 6 weeks after the BtA injection, corroborating the findings of previous studies [3, 14, 29]. According to the pharmacologic BtA effect, which lasts approximately 6 weeks [1], in our study there was a decline of this improvement 18 weeks after the injection. However, 18 weeks after the injection there was slight improvement in minimum knee flexion during stance phase, but the mean value of knee hyperextension was still 6.2°, which indicates a persisting genu recurvatum.

In this study 22 limbs of 13 children were included and analyzed. Because four patients showed a unilateral recurvatum gait, the unaffected limbs were excluded from further investigation. To enhance the power of the statistics, randomization of the bilateral limbs was done before the ANOVA was applied. Furthermore, a power analysis was done. However, a beta error caused by the small sample size and inclusion of unilateral and bilateral affected knees should be considered. Another limitation is that patients with a partially fixed equinus deformity were included. Because BtA injections are not indicated for fixed equinus deformities (no passive ankle correction in clinical examination) [8], we only excluded fixed deformities. In this study, the patients with a partially fixed equinus also showed significant improvement in ankle dorsiflexion, which supports the decision to include partially fixed deformities. However, studies analyzing the influence of BtA injections in the gastrocsoleus muscle complex on knee hyperextension in patients with a recurvatum gait exclusively are lacking in the literature. Our study includes the largest group of patients with primary genu recurvatum diplegic CP who received BtA injections and that was analyzed by 3-D gait analysis afterward.

Additional factors suspected to cause or aggravate recurvatum gait have been reported [24, 28, 30, 34]. In addition to equinus deformity, weakening of the hamstrings is mentioned frequently in this context [24, 34], which we did not address in our study. Additional hypotheses such as increased anterior pelvic tilt, increased anterior trunk lean, or shortening of the rectus femoris which may cause recurvatum gait, were not included nor analyzed in the current study. Because the purpose of our study was to focus on the effect of BtA injections in the calf muscles on genu recurvatum, additional factors like weakness of the hamstrings, shortening of the rectus femoris, and increased anterior pelvic or trunk lean were not evaluated. In this retrospective analysis three limbs received Botox (Allergan Inc) while the others received Dysport (Ipsen Biopharm Ltd). Because the results after injections of Botox and Dysport are similar [14], the patients who received Botox were not excluded from the study. Furthermore in five children, multilevel BtA injections were given. A comparison between the different subgroups of these patients who received multilevel injections did not show any significant differences, but owing to the small sample size (five children), a valid statistical test does not seem possible.

Bang et al. [13] and Sutherland et al. [28] reported a reduction of genu recurvatum after treatment of equinus deformity by injection with BtA into the calf muscles [3, 26]. In our study there was a slight reduction of recurvatum gait. Bang et al. [3, 13, 26] focused on the effects of BtA on equinus and therefore included patients with flexed knee gait and some with genu recurvatum. Because their studies did not focus on patients showing primary recurvatum gait and dynamic equinus deformity exclusively, their contrary findings are not comparable to ours.

Our findings of failed reduction in knee hyperextension after attenuation of the calf muscles by BtA are supported by the findings of Baddar et al. [2]. They found no increase in minimum knee flexion after midcalf muscle lengthening in subjects showing equinus deformity. Furthermore, they reported an increase of knee extension attributable to the uncoupling of the ankle and knee at foot contact [2]. Baddar et al. [2] did not focus on patients with recurvatum gait, but the mechanism of a coupled motion between the ankle and knee is most likely equal. This plantar-flexion-knee-extension couple, which probably is mediated by the gastrocnemius-soleus tendon unit, suggests the idea of an ankle movement into equinus while the knee extends during stance phase. Baddar et al. [2] hypothesized an increase in ankle dorsiflexion and knee extension after uncoupling of the knee and ankle by lengthening of the gastrocsoleus muscle. In our study, we observed a slight reduction by 6.2° knee hyperextension 18 weeks after the BtA injections. The effect of BtA injections may be inferior compared with the attenuating effect of surgical lengthening of the calf muscles. Therefore BtA injections may not lead to total uncoupling of the ankle and knee. However, the observed lack of response for knee hyperextension after BtA injections into the calf muscles may have different reasons. First, an overall lack of response, ie, a failed BtA injection, should be discussed. Because we detected a significant (p < 0.05) improvement of 9.1° in maximum ankle dorsiflexion 6 weeks after BtA injection, a lack of relevant reduction of genu recurvatum caused by a failed BtA injection seems unlikely. Since the first target of the BtA injection was the gastrocsoleus complex, it is possible the influence of the injection on the knee was too little for an optimal and strong effect. This may be another explanation for the weak changes in knee hyperextension with a reduction of 6.2° 18 weeks after the injection.

Another hypothesis explaining the absence of relevant recurvatum gait reduction is that of an overestimated influence of the PFKE couple on genu recurvatum. Weakening of the calf muscle complex may enlarge knee extension owing to impairment of the proximal part of the gastrocnemius muscle, which has a flexion moment on the knee [2]. This hypothesis would further agree with findings of Baddar et al. [2]. The gastrocsoleus muscle complex has multiple functions. Although the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles generate the Achilles tendon and influence the ankle-subtalar complex, only the gastrocnemius crosses the knee [2]. Weakening of the proximal gastrocnemius muscle by BtA injections could have an influence on the knee. This effect may counteract the reduction of the PFKE couple owing to equinus correction [1]. Considering the mechanism of knee function and the influence of the calf muscles, the function of the PFKE couple, ie, knee extension— is produced by the soleus muscle [1, 2]. If the PFKE couple would represent the major underlying mechanism of genu recurvatum in patients with CP with equinus, a significant improvement of recurvatum gait in the 18 limbs that received additional BtA in the soleus muscle should be expected. There are limbs with improvement after the injections (Fig. 1). There were four limbs (18%) showing a reduction of knee hyperextension. Considering that equinus is supposedly the main underlying factor in genu recurvatum, a much higher response rate would be expected.

Respecting previous studies showing an opposite function of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles at the knee, the gastrocnemius produces flexion accelerations in normal and pathologic gait [16, 19, 25, 27]. This, in combination with our findings, leads to the assumption that the soleus muscle might be a more important target than the gastrocnemius in treatment of genu recurvatum by BtA. Therefore, the treatment with BtA injections in the calf muscles provides excellent reduction of a dynamic or partially fixed equinus deformity, but a reduction of a coexisting recurvatum gait seems to be unlikely.

The PFKE couple is seen as the major factor leading to genu recurvatum in patients with CP with equinus. BtA injections in the calf muscles are a common treatment option to reduce equinus. Consequently, as an effect of equinus reduction, the PFKE couple should be reduced and knee hyperextension should resolve. A significant improvement in ankle dorsiflexion of 9.1° was seen in our patients indicating successful equinus treatment. However, there was no relevant improvement in genu recurvatum. This suggests that other factors than the PFKE couple influence the mechanism of knee hyperextension during stance. However, concomitant relevant changes in the knee kinematics are not to be expected, which leads to the conclusion that BtA injections in the calf muscles seem not to be effective in treating recurvatum gait.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simone Gantz for completing the statistics in this study, and the staff of Heidelberg’s motion laboratory for assistance in collecting the data.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Aiona MD, Sussman MD. Treatment of spastic diplegia in patients with cerebral palsy: Part II. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:S13–S38. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200405000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baddar A, Granata K, Damiano DL, Carmines DV, Blanco JS, Abel MF. Ankle and knee coupling in patients with spastic diplegia: effects of gastrocnemius-soleus lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:736–744. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang MS, Chung SG, Kim SB, Kim SJ. Change of dynamic gastrocnemius and soleus muscle length after block of spastic calf muscle in cerebral palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:760–764. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks HH. The knee and cerebral palsy. Orthop Clin North Am. 1972;3:113–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks HH. The management of spastic deformities of the foot and ankle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;122:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosgrove AP, Corry IS, Graham HK. Botulinum toxin in the management of the lower limb in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36:386–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fry NR, Gough M, McNee AE, Shortland AP. Changes in the volume and length of the medial gastrocnemius after surgical recession in children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:769–774. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181558943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham HK, Aoki KR, Autti-Ramo I, Boyd RN, Delgado MR, Gaebler-Spira DJ, Gormley ME, Guyer BM, Heinen F, Holton AF, Matthews D, Molenaers G, Motta F, Garcia Ruiz PJ, Wissel J. Recommendations for the use of botulinum toxin type A in the management of cerebral palsy. Gait Posture. 2000;11:67–79. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(99)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayek S, Gershon A, Wientroub S, Yizhar Z. The effect of injections of botulinum toxin type A combined with casting on the equinus gait of children with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1152–1159. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.23086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houltram J, Noble I, Boyd RN, Corry I, Flett P, Graham HK. Botulinum toxin type A in the management of equinus in children with cerebral palsy: an evidence-based economic evaluation. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8(suppl 5):194–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:383–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim K, Shin HI, Kwon BS, Kim SJ, Jung IY, Bang MS. Neuronox versus BOTOX for spastic equinus gait in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled multicentre clinical trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koog YH, Min BI. Effects of botulinum toxin A on calf muscles in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:685–700. doi: 10.1177/0269215510367557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CL, Bleck EE. Surgical correction of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980;22:287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu MQ, Anderson FC, Schwartz MH, Delp SL. Muscle contributions to support and progression over a range of walking speeds. J Biomech. 2008;41:3243–3252. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maanum G, Jahnsen R, Stanghelle JK, Sandvik L, Keller A. Effects of botulinum toxin A in ambulant adults with spastic cerebral palsy: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled-trial. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:338–347. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metaxiotis D, Siebel A, Doederlein L. Repeated botulinum toxin A injections in the treatment of spastic equinus foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;394:177–185. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200201000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neptune RR, Kautz SA, Zajac FE. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. J Biomech. 2001;34:1387–1398. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olney BW, Williams PF, Menelaus MB. Treatment of spastic equinus by aponeurosis lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:422–425. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry J, Hoffer MM, Giovan P, Antonelli D, Greenberg R. Gait analysis of the triceps surae in cerebral palsy: a preoperative and postoperative clinical and electromyographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:511–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polak F, Morton R, Ward C, Wallace WA, Doderlein L, Siebel A. Double-blind comparison study of two doses of botulinum toxin A injected into calf muscles in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:551–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2002.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodda JM, Graham HK, Carson L, Galea MP, Wolfe R. Sagittal gait patterns in spastic diplegia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:251–258. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saraph V, Zwick EB, Uitz C, Linhart W, Steinwender G. The Baumann procedure for fixed contracture of the gastrosoleus in cerebral palsy: evaluation of function of the ankle after multilevel surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:535–540. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B4.9850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon SR, Deutsch SD, Nuzzo RM, Mansour MJ, Jackson JL, Koskinen M, Rosenthal RK. Genu recurvatum in spastic cerebral palsy: report on findings by gait analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:882–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele KM, Seth A, Hicks JL, Schwartz MS, Delp SL. Muscle contributions to support and progression during single-limb stance in crouch gait. J Biomech. 2010;43:2099–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutherland DH, Cooper L, Daniel D. The role of the ankle plantar flexors in normal walking. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:354–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutherland DH, Davids JR. Common gait abnormalities of the knee in cerebral palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;288:139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutherland DH, Kaufman KR, Wyatt MP, Chambers HG. Injection of botulinum A toxin into the gastrocnemius muscle of patients with cerebral palsy: a 3-dimensional motion analysis study. Gait Posture. 1996;4:269–279. doi: 10.1016/0966-6362(95)01054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutherland DH, Kaufman KR, Wyatt MP, Chambers HG, Mubarak SJ. Double-blind study of botulinum A toxin injections into the gastrocnemius muscle in patients with cerebral palsy. Gait Posture. 1999;10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(99)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svehlik M, Zwick EB, Steinwender G, Saraph V, Linhart WE. Genu recurvatum in cerebral palsy–part A: influence of dynamic and fixed equinus deformity on the timing of knee recurvatum in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:366–372. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e32833a5f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi S, Shrestha A. The vulpius procedure for correction of equinus deformity in patients with hemiplegia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:978–980. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B7.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wren TA, Rethlefsen S, Kay RM. Prevalence of specific gait abnormalities in children with cerebral palsy: influence of cerebral palsy subtype, age, and previous surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:79–83. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yngve DA, Chambers C. Vulpius and Z-lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:759–764. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zwick EB, Svehlik M, Steinwender G, Saraph V, Linhart WE. Genu recurvatum in cerebral palsy–part B: hamstrings are abnormally long in children with cerebral palsy showing knee recurvatum. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:373–378. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e32833822d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]