Abstract

Background

Two decision analyses on managing the contralateral, unaffected hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) have failed to yield consistent recommendations. Missing from both, however, are sufficient data on the risks associated with prophylactic pinning using modern surgical techniques.

Questions/purposes

We determined the incidence and nature of complications after contemporary prophylactic fixation of the contralateral, unaffected hip in patients with a unilateral SCFE.

Methods

We retrospectively identified and reviewed 99 children (mean age, 11 years; range, 8–15 years) who underwent prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after treatment of a unilateral SCFE at four tertiary-care children’s hospitals from 2001 to 2010. Complications on the prophylactic side, such as avascular necrosis (AVN), chondrolysis, fractures, implant pain, and need for further surgery, were recorded. Minimum followup was 12 months (median, 26 months; range, 12–110 months).

Results

On the prophylactic side, we found two cases of focal AVN (2%) and no cases of chondrolysis (0%). Two patients sustained periimplant femur fractures (2%). Three patients had symptomatic hardware (3%), two of whom required surgery for implant removal. In three patients (3%), growth occurred off the end of the prophylactic screw before physeal closure, but they did not require revision fixation. No patients developed a subsequent slip on the side of the prophylactic pinning.

Conclusions

While prophylactic pinning prevents SCFE, it is not an entirely benign procedure. The possibility of developing complications such as AVN and periimplant fracture should be considered when determining the best management for the contralateral hip in patients who present with unilateral SCFE.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The best management of the contralateral, unaffected hip in patients who present with a unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) remains controversial. The frequency of a subsequent slip on the side that is initially normal is reportedly between 14% and 40% [12, 14, 15, 18, 22, 26]. Many authors support routine prophylactic pinning of the contralateral, normal side to prevent the morbidity associated with a subsequent SCFE, which can include pain and loss of motion, as well as the development of femoroacetabular impingement, chondrolysis, and avascular necrosis (AVN) [8, 11, 12, 16, 20, 22, 23, 26]. Others argue routine prophylactic pinning for all patients with a unilateral SCFE will result in an unnecessary surgery for most patients [6, 7, 14, 15].

Two previous decision analyses attempted to clarify the role of prophylactic pinning in patients with a unilateral SCFE but failed to yield consistent recommendations [15, 22]. As with any decision analysis, the final conclusions depend on the data used to estimate the incidence of potential complications related to each treatment option. To this point, most of the literature available on the risks of prophylactic pinning is outdated and based on the use of multiple pins without or with intraoperative imaging, rather than the current and accepted technique of a single large cannulated screw confirmed using modern C-arm image intensifiers [3, 5, 10, 13, 19, 21, 23]. Up-to-date data regarding the current risks of prophylactic screw fixation are essential for constructing an accurate prediction model to determine whether prophylactic pinning is justified.

In addition, it has been our experience that, although rare, substantial complications, including both AVN and fracture, can occur after prophylactic pinning. While the latter complication has been reported previously in the literature, the former has not.

We therefore (1) determined the incidence and nature of complications after prophylactic fixation of the contralateral, unaffected hip using modern surgical techniques and (2) explored preliminarily the relationship between implant position and the development of subsequent complications.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively identified all 128 children who underwent prophylactic pinning of the contralateral, unaffected hip after in situ fixation of a unilateral SCFE with a single screw at four large tertiary-care children’s hospitals from 2001 to 2010. Patients with underlying syndromes or endocrinopathies were excluded from this study. Twenty-nine of the 128 patients (22.6%) had inadequate followup, leaving 99 patients. There were 55 boys and 44 girls with a mean age of 11 years (range, 8–15 years). Minimum followup was 12 months (median, 26 months; range, 12–110 months). No patients were recalled specifically for this study; all data were obtained from medical records and radiographs. We obtained prior institutional review board approval from each respective institution.

All patients were pinned using modern C-arm image intensifiers. Eighty-one patients were pinned with a single 7.3-mm cannulated screw and 31 patients with a single 6.5-mm cannulated screw. Sixty-six patients had pinnings performed on a radiolucent table with both legs draped free. Twenty-three patients had each side pinned sequentially on a fracture table.

Patients were generally seen in followup at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after surgery. Assuming a normal clinical course, the patients were then seen at 1 year after surgery and yearly thereafter. At each visit, both the affected hip and the side that was prophylactically pinned were examined for pain and ROM. AP and frog lateral views were obtained at each visit. Based on the medical records, we recorded demographic factors, type of implant, and specific complications on the prophylactic side, including AVN, chondrolysis, fractures, implant pain, infection, and need for further surgery. According to a recent orthopaedic adaptation of the validated Clavien-Dindo classification [9] for surgical complications, AVN and chondrolysis were considered Grade IV complications [24]; fracture, deep infection, implant pain requiring removal, and unplanned surgery for any other reason were considered Grade III complications; and superficial infection and implant pain that did not require removal were considered Grade II complications. We did not measure Grade I complications, which were defined as complications that required no treatment or deviation from normal followup routines (eg, postoperative nausea, constipation, minor wound problem).

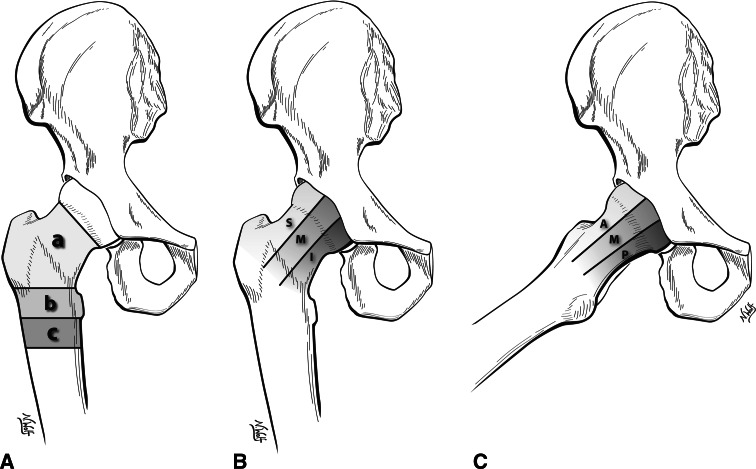

For each patient, one author from the corresponding institution who was not the treating surgeon (ENN, CL, AAA, BJS) reviewed the radiographic records to determine implant position (number of threads across the physis, entry site, and tip position). Entry site was classified as being above, at, or below the level of the lesser trochanter (Fig. 1A). The position of the tip of the implant was classified using both AP and frog lateral views of the hip. On the AP view, the implant tip was classified as being superior, middle, or inferior (Fig. 1B). On the lateral view, the implant tip was classified as being anterior, middle, or posterior (Fig. 1C). This resulted in nine possible screw tip positions. In addition, the distance between the tip of the implant and the joint surface was defined as the closest distance on either view (AP or frog) as measured using standard PACS® software (Phillips Healthcare Informatics Inc, Foster City, CA, USA).

Fig. 1A–C.

Diagrams illustrate the grading system for prophylactic screw position. (A) Entry site is classified as being above (a), at (b), or below (c) the level of the lesser trochanter. (B) On the AP view, the implant tip is classified as being superior (S), middle (M), or inferior (I). (C) On the lateral view, the implant tip is classified as being anterior (A), middle (M), or posterior (P).

Results

Of the 99 patients in our series who underwent prophylactic fixation of their unaffected hips, we found two cases of AVN (2%) and no cases of chondrolysis (0%). One of the children who developed AVN underwent removal of her implant, but at most recent followup 3 years after pinning, she had healing of her necrotic segment and was pain-free with all activities (Fig. 2). The other child with AVN underwent implant removal and later a core decompression, iliac bone marrow injection, and arthroscopic osteochondroplasty. Thirty months after the initial pinning, he complained of intermittent pain and stiffness with restricted activities.

Fig. 2.

An AP radiograph shows the pelvis of a 10-year-old girl after in situ fixation of a right SCFE and prophylactic fixation of the left hip. The prophylactic side has developed focal AVN.

Two patients sustained periimplant femur fractures (2%) within a month of surgery that required treatment with open reduction and internal fixation (Fig. 3). Both patients are currently pain-free and are back to their baseline activity level. Three patients had symptomatic hardware, two of whom required repeat surgery for implant removal (2%). Both of these patients reported resolution of their symptoms after implant removal despite the fact that one child suffered a broken screw during the removal surgery. In three patients (3%), growth occurred off the end of the prophylactic screw before physeal closure, but they did not require revision fixation.

Fig. 3A–C.

(A) An AP radiograph of the pelvis of an 11-year-old boy 4 weeks after prophylactic fixation of the right hip demonstrates a subtrochanteric femur fracture. (B) AP and (C) frog lateral views of the pelvis 3 years after open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture with a reconstruction nail demonstrate complete healing.

No patients developed superficial or deep infections or a subsequent slip on the side of the prophylactic pinning. Counting major complications (Grades III and IV), our overall complication rate from prophylactic pinning was 6%.

With regard to implant position, 55 of 99 hips (56%) had an entry site above the level of the lesser trochanter, 33 hips (33%) an entry site at the level of the lesser trochanter, and 11 hips (11%) an entry site below the level of the lesser trochanter. In both cases of periimplant fracture, the screw entered at the level of the lesser trochanter. The mean distance between the joint and the tip of the implant was 6.9 mm (range, 1.2–15.7 mm). Of the two cases of AVN, one prophylactic screw was placed middle-middle with a screw tip-joint distance of 6.4 mm and the other was placed in the anterior-superior region with a screw tip-joint distance of 13.1 mm (Table 1). Four patients (4%) had only two threads of the screw past the physis on the immediate postoperative radiographs, 21 patients (21%) had three threads past the physis, and 74 patients (75%) had four or more threads past the physis. Of the three patients who had growth off the end of the prophylactic screw, the first was a 9-year-old girl who had two threads across the physis, the second was a 10-year-old boy who had four threads of the screw across the physis, and the third was an 8-year-old girl with five threads across the physis.

Table 1.

Distribution of prophylactic screw tip positions

| Position of screw tip on frog lateral view | Number of hips | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Position of screw tip on AP view | |||

| Superior | Middle | Inferior | |

| Anterior | 9 (1)* | 7 | 2 |

| Middle | 4 | 34 (1)* | 5 |

| Posterior | 5 | 17 | 16 |

* The number of hips that developed avascular necrosis is in parentheses.

Discussion

Whether or not to prophylactically pin the contralateral side in a patient who initially presents with a unilateral SCFE remains an area of controversy despite two previous decision analyses attempting to answer this question [15, 22]. In 2002, Schultz et al. [22] recommended routine prophylactic pinning for all patients after performing a decision analysis based on functional outcome (Iowa hip score). In 2004, however, Kocher et al. [15] constructed a decision analysis based on patient preference and determined observation rather than pinning is preferred for most patients. The accuracy of any decision analysis, however, depends on the quality of the data used to weight each possible outcome. In particular, relatively few data exist in the literature describing the risks of prophylactic pinning from the more widespread technique of a single large cannulated screw placed using modern C-arm image intensifiers. We therefore determined the incidence and nature of complications after prophylactic fixation of the contralateral unaffected hip using modern surgical techniques and explored preliminarily the relationship between implant position and the development of subsequent complications.

We recognize certain limitations to our study. First, we had a limited sample size. Although this is the largest reported series of patients prophylactically pinned using modern imaging and a large cannulated screw, we lacked sufficient numbers of complications to definitively determine whether implant position influenced the risk of developing an adverse event. We hope, however, the scheme that we created to categorize implant position could be used by future authors to analyze larger numbers of patients in a systematic manner. Second, the strength of any retrospective study hinges on the quality and completeness of the medical record and missing data. As an example to this point, we were unable to determine how many times the guidewire was inserted into the proximal femur before placing the definitive fixation. Clearly, multiple passes could increase the risk of iatrogenic fracture, and errant guidewire placement could jeopardize the epiphyseal blood supply. In addition, we could not determine whether the joint was inadvertently penetrated at any point during the procedure, although we did not find any cases of chondrolysis in this series. Third, we excluded patients with endocrinopathies and syndromes. We initially excluded this population because we believed it would lead to an overestimation in the complication rate associated with prophylactic pinning. In addition, we believed this group to be too heterogeneous to study as a single subcohort. We acknowledge patients with endocrinopathies and syndromes are considered at higher risk for a subsequent slip and therefore represent a population that is often prophylactically pinned; future studies in this area should consider including patients with these diagnoses.

The complication rate in our series from prophylactic fixation is somewhat higher than those in previous reports in the literature using similar techniques and implants (Table 2). In the French literature, Ghanem et al. [11] reported on 74 patients with unilateral SCFEs who underwent prophylactic fixation using a single cannulated holothreaded screw. They reported one case (1.4%) of periimplant fracture; two additional patients developed a slip after premature removal of the screw. The authors reported no cases of AVN, chondrolysis, or infection. More recently, Dewnany and Radford [8] reported a series of 65 patients prophylactically pinned using a single large cannulated screw and modern C-arm imaging. One patient (1.5%) developed a superficial wound infection, but there were no cases of AVN, chondrolysis, or pain requiring implant removal. Finally, Kumm et al. [16] described 34 patients with SCFE treated with prophylactic dynamic screw fixation of the unaffected hip. The authors reported no complications in their series.

Table 2.

Incidence and complications of prophylactic fixation

| Study | Number of patients | Fixation | Mean followup (years) | Periimplant fracture (number of patients) | AVN (number of patients) | Infection (number of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dewnany and Radford [8] | 65 | Single large (7.0-mm) cannulated screw | 6.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Ghanem et al. [11] | 74 | Single large holothreaded screw | 5.5 | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Kumm et al. [16] | 34 | Single large (7.0-mm) cannulated dynamic screw | 5.4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Current study | 99 | Single large (6.5-/7.3-mm) cannulated screw | 2.7 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

AVN = avascular necrosis.

A concerning finding from our series are the two patients who developed osteonecrosis. To our knowledge, these are the first two cases of AVN as a result of modern prophylactic pinning that have been reported in the literature. While other complications are more easily remedied, osteonecrosis can have irreversible and profound effects on health and function of the hip and the life of these young patients.

Based on the data from in situ fixation of stable SCFEs, a single large cannulated screw placed in the center-center position has become preferred over the use of multiple pins because of a lower complication rate [1, 2, 10, 17]. Brodetti [4] demonstrated the lateral epiphyseal blood vessels enter the epiphysis posterosuperiorly. The placement of implants into this quadrant, therefore, could potentially jeopardize the vascularity of the epiphysis [2]. In addition, it is generally believed screw entry below the level of the lesser trochanter increases the risk of periimplant fracture [25]. In our series of prophylactic pinnings, both cases of periimplant fracture occurred with screws entering at, but not below, the level of the lesser trochanter. One case of AVN occurred after an implant was placed in the anterosuperior quadrant, but the other resulted from a screw placed in the middle-middle position. The small number of patients with each complication, however, limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding the effect of prophylactic screw position on the risk of developing a subsequent complication.

Based on our findings and previous results from the literature, prophylactic screw fixation of the unaffected hip in patients who present with a unilateral SCFE does prevent subsequent slip but it is not an entirely benign procedure. Complications can and do occur, including AVN, fracture, and implant pain, even with modern surgical techniques. The incidence and nature of these complications should be discussed with families as part of the shared decision-making process when choosing whether or not to prophylactically pin the unaffected hip in patients who initially present with a unilateral SCFE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hassan Azimi, BS, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, CO, USA, for his assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This study was performed at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Contributor Information

Wudbhav N. Sankar, sankarw@email.chop.edu.

Eduardo N. Novais, Email: eduardo.novais@childrenscolorado.org.

Benjamin J. Shore, Email: Benjamin.shore@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Aronsson DD, Carlson WE. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a prospective study of fixation with a single screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:810–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronsson DD, Loder RT, Breur GJ, Weinstein SL. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:666–679. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellemans J, Fabry G, Molenaers G, Lammens J, Moens P. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a long-term follow-up with special emphasis on the capacities for remodeling. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:151–157. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199605030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodetti A. The blood supply of the femoral neck and head in relation to the damaging effects of nails and screws. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1960;42:794–801. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlioz H, Vogt JC, Barba L, Doursounian L. Treatment of slipped upper femoral epiphysis: 80 cases operated on over 10 years (1968–1978) J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:153–161. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro FP, Bennett JT, Doulens K. Epidemiological perspective on prophylactic pinning in patients with unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:745–748. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford AH. Current concepts review: slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1422–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewnany G, Radford P. Prophylactic contralateral fixation in slipped upper femoral epiphysis: is it safe? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:429–433. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery RJ, Todd RC, Dunn DM. Prophylactic pinning in slipped upper femoral epiphysis: prevention of complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:217–219. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B2.2312558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanem I, Damsin JP, Carlioz H. [Contralateral preventive screwing in proximal femoral epiphysiolysis] [in French. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1996;82:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagglund G, Hansson LI, Ordeberg G, Sandstrom S. Bilaterality in slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:179–181. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B2.3346283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansson LI. Osteosynthesis with the hook-pin in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:87–96. doi: 10.3109/17453678208992184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerre R, Billing L, Hansson G, Wallin J. The contralateral hip in patients primarily treated for unilateral slipped upper femoral epiphysis: long-term follow-up of 61 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:563–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Hresko MT, Millis MB, Kim YJ, Kasser JR. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2658–2665. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200412000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumm DA, Schmidt J, Eisenburger SH, Rutt J, Hackenbroch MH. Prophylactic dynamic screw fixation of the asymptomatic hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:249–253. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199603000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loder RT, Aronson DD, Dobbs MB, Weinstein SL. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:555–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epidemiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1141–1147. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Beirne J, McLoughlin R, Dowling F, Fogarty E, Regan B. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis: internal fixation using single central pins. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:304–307. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plotz GM, Prymka M, Hassenpflug J. Role of prophylactic pinning in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis—a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:631–634. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rostoucher P, Bensahel H, Pennecot GF, Kaewpornsawan K, Mazda K. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: evaluation of different modes of treatment. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:96–101. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199605020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz WR, Weinstein JN, Weinstein SL, Smith BG. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: evaluation of long-term outcome for the contralateral hip with use of decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1305–1314. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seller K, Raab P, Wild A, Krauspe R. Risk-benefit analysis of prophylactic pinning in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, Gilbert JC, Clohisy J. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2220–2226. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2343-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skaggs DL, Flynn JM. Staying Out of Trouble in Pediatric Orthopaedics. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yildirim Y, Bautista S, Davidson RS. Chondrolysis, osteonecrosis, and slip severity in patients with subsequent contralateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:485–492. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]