Abstract

Background

There is limited knowledge regarding the relationship between the reason for revising a TKA and the clinical outcome in terms of satisfaction, pain, and function with time.

Questions/purposes

In a cohort of patients receiving a fully revised TKA, we hypothesized (1) outcomes would differ according to reason for revision at 2 years, (2) outcomes would improve gradually during those 2 years, (3) rates of complications differ depending on the reason for revision, and (4) patients with complications have lower scores.

Methods

We studied a prospective cohort of 150 patients receiving a fully revised TKA using a single implant system in two high-volume centers at 24 months of followup. VAS satisfaction, VAS pain, The Knee Society Scoring System© (KSS) clinical and functional scores, and complication rate were correlated with their reasons for revision, including septic loosening, aseptic loosening, component malposition, instability, and stiffness.

Results

The aseptic loosening group showed better outcomes compared with the instability, malposition, and septic loosening groups, which showed intermediate results (p < 0.05). The stiffness group performed significantly worse on all outcome measures. The outcome for patients with a complication, after treatment of the complication, was less favorable.

Conclusions

The reason for revision TKA predicts clinical outcomes. Satisfaction, pain reduction, and functional improvement are better and complication rates are lower after revision TKA for aseptic loosening than for other causes of failure. For component malposition, instability, and septic loosening groups, there may be more pain and a higher complication rate. For stiffness, the outcomes are less favorable in all scores.

Level of Evidence

Level III, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The indication for revision of a TKA may be related directly to the expected outcome. A revision TKA is not advocated for patients without a clear diagnosis [11, 16, 20] as these patients, if treated nonoperatively, may show improvement in function and reduction of pain with time [2, 3], and results of “exploratory” revisions are inconsistent [9, 14].

The main reasons for revision are septic loosening, aseptic loosening, polyethylene wear, pain, instability, stiffness, component malposition, and patella maltracking [12, 15, 16, 20]. The literature suggests a more favorable outcome for patients with instability, polyethylene wear, and aseptic loosening compared with patients with septic loosening and less favorable results for patients with stiffness [6, 10, 17].

However, studies regarding outcomes after revision TKA report on heterogeneous reasons for revision in patients treated with different types of implants and/or with a partial or total revision [5, 7, 8, 18]. Therefore, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions regarding outcomes after revision TKA, the recovery patterns, and the effect of complications for the different reasons for revision. The differences in outcomes are important for good patient counseling.

For these reasons, we retrospectively reviewed a prospective cohort of patients receiving a fully revised TKA using a single implant system in two high-volume centers. We sought to determine whether (1) after 2 years, the outcome in terms of VAS satisfaction, VAS pain, and The Knee Society Scoring System© (KSS) clinical and functional scores would differ according to reason for revision, (2) outcomes would improve gradually during those 2 years, (3) rates of complications differ depending on the reason for revision, and (4) patients with complications after revision TKA have lower outcome scores.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed a prospective cohort of 150 patients receiving a fully revised TKA using a single implant system in two high-volume centers at 24 months of followup (Table 1). Of 150 patients, 130 were treated at the Sint Maartenskliniek Nijmegen (The Netherlands) and the remaining 20 at the University Hospital of Leuven (Belgium). All patients were treated with the Genesis II® or Legion® revision system (Smith & Nephew, Inc, Memphis, TN, USA). The implant choice was solely time-based. Initially, all patients were treated with the Genesis II® system until August 2006, which then was replaced by the Legion® revision system. Both systems have similar femoral components, but the Legion® system allows the use of offset stems on the femoral and tibial sides. Patients were included from June 2004 to June 2008 at the Sint Maartenskliniek Nijmegen. The University Hospital of Leuven collaborated in this study from January 2007 until June 2008. Patients were not included if they underwent a partial revision, revision of a hemiarthroplasty, or received a hinged arthroplasty. Experienced orthopaedic knee surgeons performed all surgeries. During all surgeries, five or six perioperative microbiologic cultures were taken. All patients received standard postoperative rehabilitation. We report the results of 146 (99%) patients who have complete 24-month followup. In total, four patients dropped out, of whom two refused to return for the 12- and 24-month evaluations and one patient was unable to return for the 24-month evaluation owing to impaired health status not related to the revised knee. In one patient, an arthrodesis was necessary after 1 year because of persistent infection, to adequately treat the infection. The collected clinical data (KSS and VAS scores) of the patients who dropped out, available up to 12 months postoperatively, was not significantly different from the data for the patients in the same revision group. The hospitals’ investigational review boards approved the study. The Arnhem-Nijmegen Medical Ethical Review Board granted a waiver for this study.

Table 1.

General patient and surgical characteristics and baseline values of outcome measures

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at time of surgery (years)* | 66 ± 9.1 |

| Sex (male:female) (number of patients) | 49:101 |

| Side (left:right) (number of patients) | 61:89 |

| Prosthesis (Genesis II®: Legion®) | 57:93 |

| Surgery time (minutes)* | 121 ± 27 |

| Baseline values outcome measures* | |

| KSS clinical (points) | 48 ± 18 |

| KSS functional (points) | 37 ± 24 |

| VAS pain (points) | 61 ± 20 |

| ROM(°) | 93 ± 26 |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD; KSS = Knee Society Score©.

To evaluate the differences in outcome 24 months after surgery, the patients were assigned to groups according to reason for revision classified in the following five categories: septic loosening, aseptic loosening, component malposition, instability, and stiffness (Table 2). The mechanism for failure was based on preoperative evaluation and perioperative findings (Table 3). In 37 patients, more than one reason of failure could be identified. In 26 of 38 patients in the malposition group ligament laxity also was reported. In the stiff knee group, malposition (n = 8) and aseptic loosening (n = 3) were diagnosed. Stiffness was taken as the primary diagnosis in patients with limited ROM (< 70°) regardless of the underlying mechanical reason, except for patients who had revision surgery for septic loosening (Table 3). In patients with more than one reason for failure, the main failure mechanism was used for further analysis. If there was any doubt about the main reason for revision, our group of orthopaedic knee surgeons discussed the patient to resolve conflicting assessments. We found differences in preoperative KSS function among the different revision categories (p = 0.005) (Table 4). Post hoc comparison showed patients with septic loosening had a lower preoperative KSS function score (24 ± 26) compared with the patients with component malposition (47 ± 22). There were no other baseline differences among the groups; however, there was a difference in surgery time among the groups (p = 0.009).

Table 2.

Overview of indications

| Reason | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Septic loosening | 34 (23%) |

| Aseptic loosening | 40 (27%) |

| Component malposition | 38 (25%) |

| Instability | 23 (15%) |

| Stiffness | 15 (10%) |

Table 3.

Definitions of revision reasons

| Reason | Definition |

|---|---|

| Septic loosening | All patients treated with a two-stage reimplantation based on clinical suspicion or proven infection; patients with negative culture samples remained in the septic loosening group because the two-stage treatment was similar to the proven infection cases |

| Aseptic loosening | Loosening without signs of infection; polyethylene wear with emerging bone loss but no complete loosening also was included in this group |

| Malposition | Presence of clear malpositioning or malrotation of one or both components, causing pain or patella maltracking |

| Instability | Instability was defined as a clinical diagnosis with pain and instability experienced by the patient caused by a collateral ligament laxity or PCL insufficiency without any sign of component malpositioning |

| Stiffness | Stiffness was defined as a clinical condition with a limited ROM (< 70°) after TKA, with or without pain; even if the stiffness was caused by a component malposition or other earlier defined main diagnosis, these patients were solely analyzed in this single group, with the exception of patients with stiffness caused by septic loosening. These patients remained in the septic loosening group |

Table 4.

Surgical and clinical data for the reason groups

| Variable | Time | Aseptic loosening | Malposition | Instability | Septic loosening | Stiffness | Total group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery time (minutes)# | 120 ± 28 | 115 ± 24 | 108 ± 20 | 130 ± 26 | 134 ± 37 | 121 ± 27 | |

| VAS satisfaction (points) | 24 months | 78 ± 23 | 71 ± 24 | 65 ± 24 | 66 ± 32 | 48 ± 21 | 69 ± 27 |

| VAS pain score (points) | Preoperative | 58 ± 22 | 61 ± 19 | 63 ± 18 | 60 ± 20 | 62 ± 24 | 61 ± 20 |

| 24 months | 17 ± 20 | 36 ± 29 | 36 ± 28 | 43 ± 28 | 53 ± 25 | 35 ± 28 | |

| KSS clinical score (points)* | Preoperative | 52 ± 16 | 50 ± 17 | 52 ± 14 | 48 ± 19 | 34 ± 22 | 48 ± 18 |

| 24 months | 85 ± 16 | 77 ± 22 | 77 ± 19 | 74 ± 20 | 57 ± 17 | 76 ± 20 | |

| KSS function score (points)* | Preoperative# | 39 ± 23 | 47 ± 22 | 35 ± 22 | 24 ± 26 | 42 ± 23 | 37 ± 24 |

| 24 months | 69 ± 23 | 62 ± 26 | 53 ± 21 | 61 ± 26 | 45 ± 40† | 61 ± 27 | |

| ROM (°) | Preoperative | 106 ± 14 | 101 ± 16 | 102 ± 12 | 79 ± 30 | 55 ± 22 | 93 ± 26 |

| 24 months | 112 ± 13 | 110 ± 14 | 116 ± 11 | 101 ± 16 | 83 ± 22 | 107 ± 17 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD; * minimum clinically important difference is 11 points for KSS clinical score and 15 points for KSS function score; †improvement less than minimum clinically important difference; KSS = The Knee Society Scoring System©; #significantly different between the reason groups.

All patients were evaluated preoperatively, perioperatively, and postoperatively at 3, 12, and 24 months. Questionnaires were completed by a physician or a nurse practitioner and the patient; a 100-mm VAS for pain (0 = excellent) and patient satisfaction (100 = excellent) and the KSS using the clinical and functional scores were included. In addition, ROM, an item on the KSS clinical score, was analyzed separately.

Complications were defined as any type of adverse events related to functioning of the revision implant, including conservative treatments and operative treatments. Baseline status of the different revision categories was compared using one-way ANOVA and chi-square test or the appropriate nonparametric alternatives. Differences in the outcome measures between the revision groups and improvement with time were examined using repeated-measures analysis. In this analysis, missing data points were replaced with the mean value of the total group for that variable to create a noninformative data point without having to eliminate patients with missing data. Additionally, the missing data points were replaced, using a worst-case scenario, by the preoperative score assuming no positive postoperative effect had been achieved, to have an idea of the lower boundaries of the results. This analysis showed the same significant effects, implying the missing data did not influence the results. Differences between reason groups were identified with post hoc tests (Student-Newman-Keuls test). This test showed which subset of revision groups was significantly different compared with the other groups (p < 0.05). Comparison of outcome measures was performed using the Mann-Whitney test for patients with and without any type of complication or a complication with operative treatment. In all analyses, the level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Data analysis was performed using the statistical package of SPSS® 12.0.1 for Windows® (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

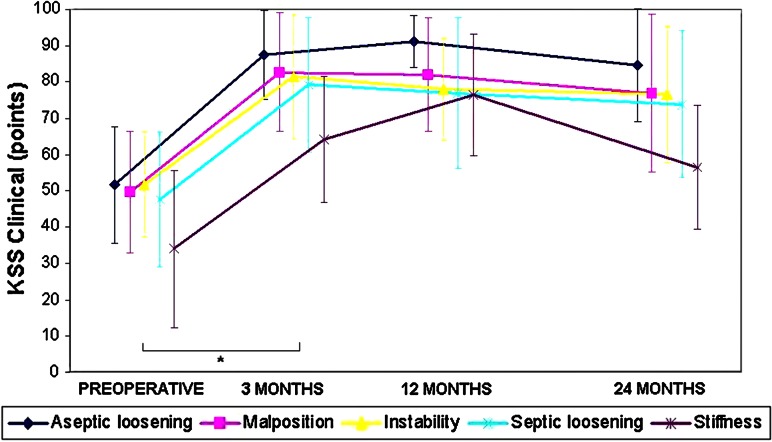

The VAS score for satisfaction, VAS pain score, and KSS clinical score were dependent on the reason for revision, respectively p = 0.006, p = 0.002, and p < 0.001 (Figs. 1–3).

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the VAS satisfaction scores for the separate reasons for revision with time. The VAS score for satisfaction was dependent of the reason for revision (p = 0.006).

Fig. 3.

The KSS clinical scores for the separate reasons for revision with time are shown. The KSS clinical score was dependent of the reason for revision (p < 0.001) and time (p < 0.001). * = significant improvement.

Patients who had revision surgery for aseptic loosening had lower VAS pain values (p < 0.05) compared with patients in the other indication groups (Fig. 2). Patients in the stiffness group reported significantly lower VAS scores for satisfaction (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1) and lower KSS clinical scores (p < 0.05) compared with patients in the other groups (Fig. 3). Furthermore, patients with aseptic loosening showed a trend for higher KSS clinical scores than the instability and malposition groups (p = 0.082) regardless of time (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The VAS pain scores for the separate reasons for revision with time are shown. The VAS score for pain was dependent of the reason for revision (p = 0.002) and time (p < 0.001). * = significant improvement.

The KSS functional score (Fig. 4) and ROM (Fig. 5) were not significantly dependent on the reason for revision.

Fig. 4.

The KSS functional scores for the separate reasons for revision with time are shown. A significant interaction of time and reason for revision was found (p = 0.010).

Fig. 5.

A graph shows ROM for the separate reasons for revision with time. A significant interaction of time and reason for revision was found (p = 0.001).

A significant improvement for VAS pain score (Fig. 2) and KSS clinical score (Fig. 3) for the total group was seen with time (p < 0.001). The greatest improvement occurred during the first 3 months after surgery for the VAS pain and KSS clinical scores, with p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 when comparing the 3-month and preoperative values.

The KSS functional score (Fig. 4) and ROM (Fig. 5) showed an interaction of time and reason for revision (F12,435 = 2.23, p = 0.010; F12,435 = 3.161, p = 0.001, respectively), meaning the improvement with time was different for the different revision groups. In all but the stiffness group, the largest improvement in KSS functional score was seen 3 months after surgery.

The complication rates for each category, listed from highest to lowest overall rate, are instability (nine of 23, 39%), stiffness (nine of 15, 33%), septic loosening (10 of 34, 29%), malposition (11 of 38, 29%), and aseptic loosening (four of 40, 10%) (Table 5), which were not significantly different (p = 0.085). There were 22 complications requiring operative treatment, whereas 19 complications were treated conservatively. When comparing the number of additional operative treatments, there was a significant difference (p = 0.009) between the groups.

Table 5.

Procedure-related complications

| Variable | Aseptic loosening | Malposition | Instability | Septic loosening | Stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 40 | 38 | 23 | 34 | 15 |

| Infection | |||||

| Perioperative (+) cultures | 2 | ||||

| Deep infection | |||||

| Lavage | 1 (−)* | 2 (+)* | 1 (−)* | ||

| Rerevision | 1 | ||||

| Arthrodesis | 1 | ||||

| Delayed wound healing | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Instability: exchange of insert | 3 | 2 | |||

| Patellofemoral | |||||

| Resection lateral facet | 1 | 1 | |||

| Patella resurfacing | 1 | 1 | |||

| Tuberosity fracture | 1 | ||||

| Pain clinic referral | 6 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Manipulation under anesthesia | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Number of patients with complications | 4 | 11 | 9† | 10 | 5‡ |

| Number of complications | |||||

| Nonoperative treatment | 3 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Operative treatment | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

* (−) = negative culture; (+) = positive culture; †one patient reported delayed wound healing and exchange of an insert; ‡one patient reported lavage and manipulation under anesthesia.

Overall, we found lower KSS clinical, ROM, and VAS satisfaction scores (p = 0.005, p = 0.013, and p = 0.024, respectively) for patients who reported a complication. When evaluating the different revision groups, patients treated for malposition who had a complication scored lower for all KSS outcome measures, whereas the VAS satisfaction score almost reached significance (p = 0.057). The septic loosening group with reported complications scored lower on the KSS clinical score (p = 0.046) and VAS satisfaction (p = 0.038). In the aseptic loosening, instability, and stiffness groups, no differences between patients with and without complications were found.

Discussion

There is limited knowledge regarding the relation between the reason for revising a TKA and the clinical outcome in terms of satisfaction, pain, and function with time. In a cohort of patients receiving a fully revised TKA, we sought to determine whether (1) outcomes would differ according to reason for revision at 2 years, (2) outcomes would improve gradually during those 2 years, and (3) rates of complications differ depending on the reason for revising the TKA, and (4) patients with complications after revision TKA have lower clinical scores.

Some limitations in this study have to be considered, including the small sample size in some revision groups, the potential influence of missing data, and the decision to define a main diagnosis. First, stratification into five main reasons for revision made sample sizes in each group small, causing a large SD in all presented clinical outcomes. Therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated to the individual patient. Second, the presence of missing data could cause a more favorable outcome for one group compared with the others. Therefore, we performed a worst-case scenario analysis, but this analysis showed the same significant effects and thus the missing data did not influence our results. Finally, the decision to stratify five main reasons for revision is debatable because patients with a nonfunctional TKA often have a combination of problems. The main reason was why the TKA failed (in our opinion) or why the patient sought medical attention. The stiffness and septic loosening groups were considered separate groups with their own specific characteristics (Table 3).

Considering the relation between the reason for revision and outcome, we believe that patients having revision surgery for aseptic loosening showed the best overall outcomes and those who had revision surgery for stiffness had the worst outcomes. Our findings are in concordance with results reported by Saleh et al. [18] in their meta-analysis and as reported by others [6, 10, 13, 16] (Table 6). Furthermore, when considering the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the KSS, we found good clinical results for all patient groups (Table 4). Singh et al. [19] stated that a difference of 61% of one SD in the KSS for patients with a primary TKA is a moderately large and almost certainly a clinically meaningful effect size. A possible reason for the good results in the aseptic loosening group could be that complaints in this group are caused solely by loosening of the component(s) from the bone interface without other soft tissue disorders, and this is directly addressed by the revision procedure. For the other indications where theoretically the soft tissue envelope is more involved, we found smaller improvement and less pain reduction. In case of instability, for example, the soft tissue envelop was involved, as a revision was performed only if the flexion and extension gaps were unequal as measured with stress radiographs in flexion and extension. The stiffness group had the most obvious soft tissue disorders and we found the least favorable outcomes on average. Other investigators also found significantly worse outcomes in terms of function scores and patient satisfaction for the stiffness group [1, 6, 10, 17]. Because of these poor findings, we are now cautious when doing revision surgery on patients with a stiff knee even if a clear reason has been established.

Table 6.

Studies reporting KSS and ROM after revision TKA

| Study | Number of knees | Mean age of patients (years) | Mean followup (months) | Mean KSS clinical score (points) | Mean KSS functional score (points) | Mean ROM (°) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative | Preoperative | Postoperative | Preoperative | Postoperative | ||||

| Aseptic loosening | |||||||||

| Patil et al. [16] | 13 | 40 | 41 | 72 | 28 | 51 | |||

| Current study | 40 | 24 | 52 | 85 | 39 | 69 | 106 | 112 | |

| Septic loosening | |||||||||

| Meek et al. [13] | 47 | 24 | 78 | 87 | |||||

| Patil et al. [16] | 15 | 40 | 35 | 77 | 17 | 59 | |||

| Current study | 34 | 24 | 48 | 74 | 24 | 61 | 78 | 101 | |

| Stiffness | |||||||||

| Haidukewych et al. [6] | 16 | 42 | 28 | 65 | 45 | 58 | |||

| Kim et al. [10] | 56 | 43 | 40 | 58 | 54.6 | 82.2 | |||

| Patil et al. [16] | 11 | 40 | 41 | 58 | 41 | 53 | |||

| Current study | 15 | 24 | 34 | 57 | 42 | 46 | 55 | 83 | |

| Overall | |||||||||

| Saleh et al. [18] | 574 | 66.6 | 53.1 | 32.8 | 74.9 | 30.4 | 57.4 | ||

| Current study | 150 | 66 | 24 | 48 | 76 | 37 | 60 | 93 | 107 |

KSS = The Knee Society Scoring System©.

In contrast to our belief that gradual improvement would be seen during the 24-month period, we found the largest improvement occurred during the first 3 months after surgery for all groups. The aseptic loosening, septic loosening, malposition, and instability groups showed stabilization in improvement in the following 12 to 24 months. The stiffness group showed maximal results at 3 months, staying steady until 12 months, followed by a slight decline. Generally, the 3-month postoperative scores are suggestive of the final outcome at 24 months, except for patients treated for stiffness. Similar patterns of improvement were reported by Ghomrawi et al. [5]. They found functional improvement during the first year after surgery, but during the second year there were signs of decline in function and increase of pain [5].

We found a relationship between the reason for revision and complications after 2 years. Complications were most common in the instability group. Patients in the malposition group reported frequently persistent pain and often were referred to a pain clinic. The reason for this high rate of persistent pain probably is attributable to the remaining underlying soft tissue disorder, which was not addressed during the revision procedure for malposition. For the septic loosening group, complications were, as expected, related mainly to reinfections. Complications had a negative effect on function and satisfaction, even after treatment of these complications. Patients who experienced complications had lower scores for clinical function and satisfaction. The complication rates we found are of the same order of magnitude as the 12% reoperation rate reported previously [4, 6, 13, 18]. However, the effect of complications on outcome scores was not analyzed in these studies.

Satisfaction, pain reduction, and functional improvement are better and complication rates are lower after revision TKA for aseptic loosening than for other causes of failure. For the component malposition, instability, and septic loosening groups, there may be more pain and a higher complication rate. For the stiffness group, pain, function, and satisfaction are less favorable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the orthopaedic surgeons K. C. Defoort MD (Sint Maartenskliniek) and J. Bellemans MD (University Hospital Leuven) for performing surgeries on the patients included in this study and their helpful comments during manuscript preparation. We acknowledge P. G. Anderson for helpful editorial assistance.

Footnotes

The institute of one or more of the authors (RWTMK, JJPS, GGH, ABW) has received, during the study period, funding from Smith & Nephew Inc (Memphis, TN, USA). One or more of the authors (GGH, HV, ABW) certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has received or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD (GGH: USD 10,000–USD 100,000; HV: USD 10,000–USD 100,000; ABW: USD 10,000–USD 100,000), from Smith & Nephew.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Baker P, Cowling P, Kurtz S, Jameson S, Gregg P, Deehan D. Reason for revision influences early patient outcomes after aseptic knee revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2244–2252. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brander V, Gondek S, Martin E, Stulberg SD. Pain and depression influence outcome 5 years after knee replacement surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:21–26. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elson DW, Brenkel IJ. A conservative approach is feasible in unexplained pain after knee replacement: a selected cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1042–1045. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fosco M, Filanti M, Amendola L, Savarino LM, Tigani D. Total knee arthroplasty in stiff knee compared with flexible knees. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s12306-011-0099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghomrawi HM, Kane RL, Eberly LE, Bershadsky B, Saleh KJ, North American Knee Arthroplasty Revision (NAKAR) Study Group Patterns of functional improvement after revision knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2838–2845. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haidukewych GJ, Jacofsky DJ, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT. Functional results after revision of well-fixed components for stiffness after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartley RC, Barton-Hanson NG, Finley R, Parkinson RW. Early patient outcomes after primary and revision total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:994–999. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B7.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hossain F, Patel S, Haddad FS. Midterm assessment of causes and results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1221–1228. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs MA, Hungerford DS, Krackow KA, Lennox DW. Revision total knee arthroplasty for aseptic failure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Nelson CL, Lotke PA. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty: prevalence of the complication and outcomes of revision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1479–1484. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B7.15255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lonner JH, Fehring TK, Hanssen AD, Pellegrini VD, Jr, Padgett DE, Wright TM, Potter HG. Revision total knee arthroplasty: the preoperative evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(suppl 5):64–68. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandalia V, Eyres K, Schranz P, Toms AD. Evaluation of patients with a painful total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:265–271. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B3.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meek RM, Masri BA, Dunlop D, Garbuz DS, Greidanus NV, McGraw R, Duncan CP. Patient satisfaction and functional status after treatment of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty with use of the PROSTALAC articulating spacer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1888–1892. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B8.14214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mont MA, Serna FK, Krackow KA, Hungerford DS. Exploration of radiographically normal total knee replacements for unexplained pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;331:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199610000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parratte S, Pagnano MW. Instability after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:184–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patil N, Lee K, Huddleston JI, Harris AH, Goodman SB. Aseptic versus septic revision total knee arthroplasty: patient satisfaction, outcome and quality of life improvement. Knee. 2010;17:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pun SY, Ries MD. Effect of gender and preoperative diagnosis on results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2701–2705. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0451-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleh KJ, Dyke DC, Tweedie RL, Mohamed K, Ravichandran A, Saleh RM, Gioe TJ, Heck DA. Functional outcome after total knee arthroplasty revision: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:967–977. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.35823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh J, Sloan JA, Johanson NA. Challenges with health-related quality of life assessment in arthroplasty patients: problems and solutions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:72–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toms AD, Mandalia V, Haigh R, Hopwood B. The management of patients with painful total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:143–150. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]