Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism responsible for orthopaedic surgical site infections (SSIs). Patients who are carriers for methicillin-sensitive S. aureus or methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) have a higher likelihood of having invasive S. aureus infections. Although some have advocated screening for S. aureus and decolonizing it is unclear whether these efforts reduce SSIs.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were to determine (1) whether S. aureus screening and decolonization reduce SSIs in orthopaedic patients and (2) if implementing this protocol is cost-effective.

Methods

Studies for this systematic review were identified by searching PubMed, which includes MEDLINE (1946–present), EMBASE.com (1974–present), and the Cochrane Library’s (John Wiley & Sons) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment Database (HTAD), and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED). Comprehensive literature searches were developed using EMTREE, MeSH, and keywords for each of the search concepts of decolonization, MRSA, and orthopedics/orthopedic surgery. Studies published before 1968 were excluded. We analyzed 19 studies examining the ability of the decolonization protocol to reduce SSIs and 10 studies detailing the cost-effectiveness of S. aureus screening and decolonization.

Results

All 19 studies showed a reduction in SSIs or wound complications by instituting a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol in elective orthopaedic (total joints, spine, and sports) and trauma patients. The S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol also saved costs in orthopaedic patients when comparing the costs of screening and decolonization with the reduction of SSIs.

Conclusions

Preoperative screening and decolonization of S. aureus in orthopaedic patients is a cost-effective means to reduce SSIs.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, systematic review of Level I–IV studies. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for the majority of surgical site infections (SSIs) in orthopaedic patients [3]. It is also one of the most common causes of infections in patients in intensive care [44, 53], with nosocomial bloodstream infections [37], and with healthcare-associated pneumonia [35, 50]. S. aureus is a Gram-positive aerobic bacteria often found in normal skin flora [31]. SSIs with S. aureus in orthopaedic patients are difficult to treat because this organism can form a biofilm on orthopaedic implants that is resistant to antibiotic treatment and can thereby compromise eradication of infection [32].

S. aureus resides on skin surfaces and up to 1/3 of the population is asymptomatically colonized with this organism [56]. The nares are the most common site of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) colonization [56]. In general, patients who are carriers of S. aureus have a higher likelihood of having invasive S. aureus infections [31, 56] and S. aureus isolates from the surgical site reportedly match those from the nares 85% of the time, because presence in the nares correlates with the skin carrier state [54]. Kalmeijer et al. [27] found nasal carriage of S. aureus was the only independent risk factor for S. aureus SSI after orthopaedic implant surgery. Because patients with MRSA SSIs have a higher risk of death [13] and greater median hospital costs [2] when compared with patients with MSSA or uninfected surgical site wounds, it seems prudent to decolonize surgical patients who are positive for MSSA/MRSA colonization with the hopes of reducing the incidence of SSIs.

Factors associated with surgery, including the use of antiseptic agents, handwashing, and sterile technique, all play a role in reducing infection rates [21]. Patient factors such as malnutrition [18], diabetes [59], and obesity [39] have been associated with increased rates of infection secondary to poor wound healing, and interventions such as diet and lifestyle modification may reduce infections. Multiple methods have been instituted to reduce the incidence of SSIs in orthopaedic patients, including instituting laminar air flow in the operating room [14], administering perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis [8], and using antiseptic surgical skin preparation scrubs and solutions [38]. Another method for reducing MSSA/MRSA infections is the preoperative detection of S. aureus colonization and subsequent decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body scrubs [42].

The purposes of this article were to determine (1) whether S. aureus screening and decolonization reduce SSIs in orthopaedic patients and (2) if implementing this protocol is cost-effective.

Search Strategy and Criteria

Studies for this systematic review were identified by searching PubMed, which includes MEDLINE (1946–present), EMBASE.com (1974–present), and Cochrane Library’s (John Wiley & Sons) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment Database (HTAD), and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED). Search strategies were developed by a health sciences librarian (CBW). The librarian translated the search strategies using each database platform’s command language and appropriate search fields. EMTREE, MeSH, and keywords were used for the search concepts of decolonization, MRSA, and orthopedics/orthopedic surgery. The three concepts were combined with a Boolean “AND.” No database search limits were applied and non-English language articles were included. Appendix 1 contains the search strategies in detail. To identify studies on the cost-effectiveness of S. aureus screening and decolonization, PubMed’s Health Services Research (HSR) Queries filter was used [58]. Initial searches were run from April to July 2012. Final searches were completed and updated in December 2012. Studies published before 1968 were excluded. We found a total of 2957 citations in PubMed and MEDLINE, 4581 references in EMBASE, and 402 citations in CENTRAL, bringing the total number of articles initially identified to 7940.

Two of the authors (AFC, NR) reviewed all 7940 titles and abstracts. Of these titles and abstracts, there were 1056 duplicated entries. We included articles meeting these criteria: (1) studies that evaluated S. aureus (MRSA and/or MSSA) screening in orthopaedic procedures; (2) studies that evaluated the ability of a decolonization protocol to reduce SSIs; (3) comparative studies between patients who did and did not receive S. aureus screening; and (4) studies that evaluated the economic use of implementing a S. aureus decolonization protocol. Articles were excluded if they (1) did not address S. aureus screening and only addressed orthopaedic infections with S. aureus, including osteomyelitis, abscess, spondylodiscitis, septic arthritis; (2) only studied nonorthopaedic patients (eg, general, vascular, urologic surgery); (3) analyzed antibiotic use as prophylaxis, treatment, resistance, and implant coating instead of for decolonization purposes; (4) studied surgical treatment of SSI; (5) evaluated other methods of SSI prevention (eg, chlorhexidine cloths, negative pressure wound therapy, antibiotic cement, pulse lavage, handwashing, normothermia, ring fencing only); and (6) did not include a decolonization protocol such as the evaluation of MRSA screening as a predictor of S. aureus infections.

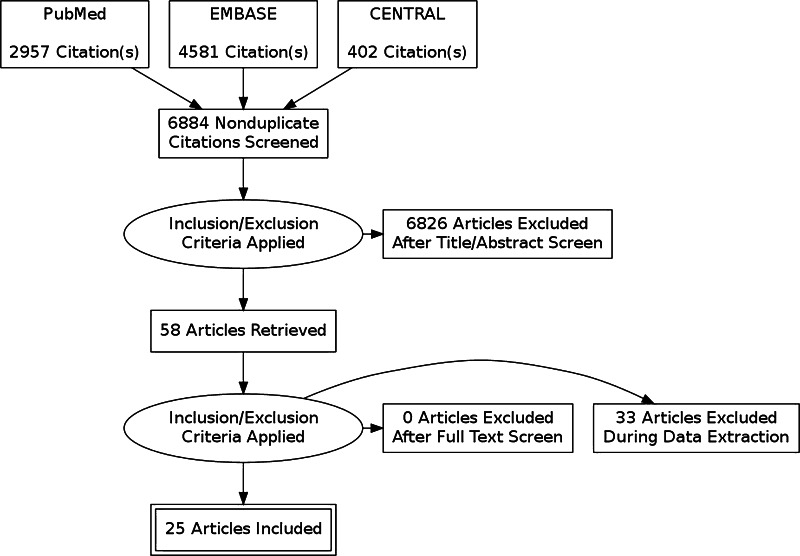

When these inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, 6826 articles were excluded, leaving 58 articles. None of the articles were excluded after a full text screen. An additional, 33 articles were excluded during data extraction for the following reasons: (1) there was no comparison group for S. aureus decolonization; (2) there was no implementation of a decolonization protocol; (3) studies evaluated the colonization of S. aureus but not SSI rates; (4) articles were review articles that reported other studies that were already included; (5) S. aureus colonization was evaluated in orthopaedic surgical team members and not patients; (6) authors did not respond to requests for additional information about S. aureus decolonization protocols; and (7) an article was a duplicate of another article but in a different language [25, 26]. This left 25 articles that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram shows the selection criteria for S. aureus screening and decolonization studies in orthopaedic surgery.

Two independent reviewers (AFC, NR) evaluated the full texts of the 25 relevant papers, and the following information was extracted: study design, aim of the study, patient population and sample size, controls, year of publication, country of publication, S. aureus (MRSA and/or MSSA) method of detection and colonization, decolonization protocol and patients who received it, definition of SSI, infection reduction of decolonization, and costs.

The methodologic quality of each article was assessed by the type of study (prospective studies were preferred), the year the study was conducted (there was a greater focus on more recent studies performed within the last 5 years), and the sample size (larger sample sizes greater than 1000 were considered more favorably to adequately power a detection in SSI reduction). Studies were categorized into good (highest level), fair, and low. These items were taken into consideration for assessing validity. The current evidence evaluating the use of S. aureus screening and decolonization in orthopaedic patients is mostly fair, because most studies were retrospective, had smaller samples, or were published before 2007. However, there were three studies that were prospective, randomized controlled trials that showed that this screening and decolonization protocol was effective in all orthopaedic patients [5, 51] and in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty and spine surgery [26].

Of the 19 studies that evaluated the ability of S. aureus screening and decolonization to reduce SSI in orthopaedic patients, there were nine prospective studies [5, 26, 30, 42, 43, 47, 49, 51, 57] and 10 retrospective studies [7, 9, 11, 16, 19, 20, 24, 29, 36, 40] (Table 1). Most studies evaluating S. aureus screening and decolonization in orthopaedic patients were conducted on patients undergoing elective total joint arthroplasty [11, 16, 19, 20, 25, 30, 42, 43, 47, 49], although many studies did evaluate all elective orthopaedic patients [5, 9, 24, 29, 36, 40, 51, 57], spine patients [7, 30], and trauma patients [36]. The majority of studies detected S. aureus colonization using cultures, most SSIs were defined by CDC criteria, the majority of studies did not differentiate between superficial versus deep infections, and most of the patients who underwent decolonization were positive for S. aureus on nasal screens (Table 2). The most commonly used decolonization protocol was 2% intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine gluconate for 3 to 5 days, which was instituted either on the day of admission or before admission. Nine of the 19 studies changed the antibiotic prophylaxis to vancomycin or teicoplanin before surgery if patients were MRSA-colonized (Table 2). Five studies reswabbed patients after decolonization to ensure they were negative, often before proceeding to surgery (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of studies evaluating Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization in orthopaedic patients

| Study | Year | Country | Study design | Patient population | Number | Controls | Number of positive S. aureus colonization | Definition of infection | Differentiation of infection location | Infection reduction with decolonization | Quality of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bode et al. [5] | 2010 | Netherlands | Prospective RCT | Combined (including orthopaedic) | 917 | Concomitant (placebos) | MRSA 19% | Positive culture | Superficial versus deep | 56% reduction in S. aureus infection | Good: prospective RCT, large sample, current |

| Chen et al. [7] | 2012 | USA | Retrospective | Spine | 1002 | Concomitant | MRSA 3% | Wound complication | No differentiation | 4% reduction in wound complications (p = 0.924) | Fair: retrospective, large sample, concomitant controls, current |

| Coskun and Aytac [9] | 2004 | Turkey | Retrospective | Orthopaedic | 1751 | Historical | No prescreen | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 57% reduction in SSI, 79% reduction in S. aureus SSI, 100% reduction in MRSA SSI | Fair: retrospective, large sample, did not determine colonization rate |

| DeLucas-Villarrubia et al. [11] | 2004 | Spain | Retrospective | Total joint | 1320 | Historical | S. aureus 24%, MRSA 5% | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 49% reduction in SSI | Fair: retrospective, large sample |

| Gernaat-van der Sluis et al. [16] | 1998 | Netherlands | Retrospective | Total joint and trauma | 2304 | Historical controls | No prescreen | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 50% reduction in SSIs, 40% reduction in S. aureus SSI | Fair: large sample, no colonization rate, older |

| Hacek et al. [19] | 2008 | USA | Retrospective | Total joint | 1495 | Historical | S. aureus 25% | CDC criteria | Superficial, deep, organ space/joint | 75% reduction of S. aureus SSIs (p ≤ 0.1) | Fair: retrospective, large sample size, consecutive patients |

| Hadley et al. [20] | 2010 | USA | Retrospective | Total joint | 2058 | Concomitant | MSSA 21%, MRSA 4% | CDC criteria | Deep infections only | 13% reduction of total SSIs (p = 0.809) | Fair: retrospective, large sample size, deep SSIs |

| Kallen et al. [24] | 2005 | USA | Systematic review | Orthopaedic | 2918 | Concomitant and historical | None reported | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 29% reduction of SSIs | Fair: combination of orthopaedic studies (Levels I to III), older |

| Kalmeijer et al. [25] | 2001 | Netherlands | Prospective RCT | Total joint and spine | 614 | Concomitant (placebo) | S. aureus 30% | CDC criteria | Superficial versus Deep | 41% reduction of total SSIs (p > 0.05) | Good: RCT; ITT analysis, older |

| Kelly et al. [29] | 2012 | Ireland | Retrospective | Orthopaedic trauma and elective | 7688 (compare 2005 with 2006) | Historical | MRSA 1% | CDC criteria | Superficial, deep, organ space/joint | 29% reduction of MRSA SSIs (p = 0.108) | Fair: retrospective, large sample, nonconcomitant controls |

| Kim et al. [30] | 2010 | USA | Prospective | Total joint, spine, sports medicine | 7019 | Historical | MSSA 23%, MRSA 4% | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 81% reduction of total SSIs (p = 0.0093) | Good: prospective, large patient cohort, recheck of MRSA colonization |

| Nixon et al. [36] | 2006 | UK | Retrospective | Elective and trauma orthopaedic | 5594 | Historical | MRSA elective 1%, MRSA trauma 4% | Positive cultures | No differentiation | Trauma patients: 56% reduction of MRSA SSIs (p = 0.035), elective patients: 70% reduction of MRSA SSIs (p = 0.06) | Fair: retrospective, large sample, separation of trauma and elective, current |

| Pofahl et al. [40] | 2009 | USA | Retrospective | Orthopaedic | 3415 | Historical | MRSA 7.2% (surgical patients) | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 100% reduction in MRSA SSIs for orthopaedic patients | Fair: retrospective, large sample, multiple surgical subspecialties |

| Rao et al. [42] | 2008 | USA | Prospective | Total joint | 1966 | Concomitant | MSSA 23%, MRSA 3% | CDC criteria | Superficial versus deep | 200% reduction of S. aureus SSIs (p = 0.016) | Fair: prospective, large sample, controls from a different group of surgeons |

| Rao et al. [43] | 2011 | USA | Prospective | Total joint | 3025 | Concomitant | MSSA 22%, MRSA 3% | CDC criteria | Superficial versus deep | 77% reduction of total SSIs (p = 0.009) | Good: prospective, larger sample, current |

| Sankar et al. [47] | 2005 | UK | Prospective | Total joint | 395 | Historical | Unknown | Unknown | No differentiation | 200% reduction of total SSIs, 83% reduction of hospital-acquired infections (p < 0.05) | Fair: prospective, small sample, older |

| Sott et al. [49] | 2001 | UK | Prospective | THA | 123 | Historical | MRSA 3% | Positive MRSA culture | Superficial versus deep | 82% reduction in MRSA SSI (superficial and deep) (p > 0.05) | Fair: prospective, small sample, older |

| van Rijen et al. [51] | 2008 | Netherlands | Cochrane review of RCTs | Surgical and medicine | 3396 | Concomitant placebos | S. aureus 23%–58% | Mix | Mix | Significant reduction in S. aureus infections (RR 0.55) | Good: compilation of RCTs, large sample |

| Wilcox et al. [57] | 2003 | UK | Prospective | Orthopaedic with insertion of metal prostheses and/or fixation | 2178 | Historical | Predecolonization: MSSA 27%, MRSA 38%; postdecolonization: MSSA 11%, MRSA 8% | CDC criteria | No differentiation | 149% reduction in MRSA SSIs (p < 0.001) | Fair: prospective, large sample, older |

ITT = intention to treat; MSSA = methicillin-sensitive S. aureus; MRSA = methicillin-resistant S. aureus; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RR = relative risk; SSI = surgical site infection.

Table 2.

Comparison of studies evaluating Staphylococcus aureus screening, decolonization, and antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopaedic patients

| Study | Method of S. aureus detection | Decolonization protocol (number of days) | Timing of decolonization | Who received decolonization | Antibiotic prophylaxis | Rescreening for S. aureus colonization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bode et al. [5] | PCR | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine gluconate soap × 5 | Day of admission | Positive nasal screens | Not stated | None |

| Chen et al. [7] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal screens | Standard/MSSA-positive = cefazolin, MRSA-positive = vancomycin | None |

| Coskun and Aytac [9] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 3 | 3 days before surgery | All patients | Cefazolin or cefuroxime | None |

| DeLucas-Villarrubia et al. [11] | Culture | Mupirocin nasal ointment × 3 | Day before surgery | All patients during intervention period | Standard = cefonicid, MRSA-positive = cefonicid and teicoplanin | None |

| Gernaat-van der Sluis et al. [16] | Culture | Mupirocin nasal ointment × 3 | Day before surgery | All patients during intervention period | Cefazolin for all patients | None |

| Hacek et al. [19] | PCR | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, TKA—Hibiclens® (Regent Medical, Norcross, GA, USA) × 1 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal screens | THA = cefazolin, TKA = vancomycin | None |

| Hadley et al. [20] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 1 | 5 days before surgery | All screened patients | MSSA = cefazolin or clindamycin, MRSA = vancomycin | None |

| Kallen et al. [24] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment | 5 days before surgery to the day of admission | Positive nasal screen | Not stated | None |

| Kalmeijer et al. [25] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment | Day before surgery | Mupirocin randomized group | Cefamandole or clindamycin for all patients | 3–5 days after surgery |

| Kelly et al. [29] | Culture | Topical mupirocin × 5, 4% chlorhexidine gluconate × 5 | Elective patients—5 days before surgery, trauma patients—day of admission | Positive nasal, axilla, and/or groin screens | Not stated | Repeat at least 3 times after decolonization until MRSA-negative |

| Kim et al. [30] | PCR | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | Minimum of 5 days before surgery to allow time for rescreening | Positive nasal screens | Standard = cefazolin, MRSA = vancomycin | Repeated before surgery to ensure carrier state was negative |

| Nixon et al. [36] | Culture | Mupirocin × 5, triclosan × 5 | Elective patients—2 weeks before admission, trauma patients—day of admission | Elective patients—positive nasal screens, trauma patients—all patients | Standard = cefuroxime, MRSA = teicoplanin | Repeat 3 times until negative |

| Pofahl et al. [40] | PCR | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, 4% chlorhexidine gluconate × 3 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal screens | At the discretion of the surgeon | None |

| Rao et al. [42] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal screens | Standard/MSSA-positive = cefazolin, MRSA-positive = vancomycin | None |

| Rao et al. [43] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal screens | Standard/MSSA positive = cefazolin, MRSA positive = vancomycin | None |

| Sankar et al. [47] | Unknown | Mupirocin, povidone-iodine, and/or triclosan | 1 week before surgery | Positive nasal, axilla, groin, or open wound screens | Cefazolin or cefuroxime | 3 times total swabbing until decolonized |

| Sott et al. [49] | Culture | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine bath × 5 | 5 days before surgery | Positive nasal, axilla, or perineum screens | Standard = second-generation cephalosporin, MRSA = suggested teicoplanin | 3 times total swabbing until decolonized |

| van Rijen et al. [51] | Mix of Culture and PCR | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment | Mix | Mupirocin randomized group | Cephradine | Mix |

| Wilcox et al. [57] | Culture | Mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, 2% triclosan × 1 | 1 day before surgery | All patients | Standard = cephradine, MRSA = vancomycin | None |

MRSA = methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA = methicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

Ten studies (Table 3) examined the cost of implementing a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol [10, 19, 22, 34, 36, 42, 43, 48, 52, 55]. The method of evaluating costs differed among studies, because four of the studies were based on economic models [10, 34, 48, 55], whereas the remainder of the studies was based on actual patient data. The economic models were based on decision trees that separated groups on the following variables: (1) treatment options in which unscreened and untreated patients were compared with decolonizing all patients or only decolonizing S. aureus-positive patients; and (2) patient populations in which patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty and spine fusion were separately analyzed.

Table 3.

Comparison of studies evaluating the economic impact associated with Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization in SSIs in orthopaedic patients

| Study | Year | Country | Patient population | Patient groups | Type of study | Decolonization protocol (number of days) | Method of S. aureus detection | Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courville et al. [10] | 2012 | USA | Total joint | 1. Screen and treat 2. Treat all 3. No screening or treatment |

Model | Mupirocin × 5 | Culture | USD 54 saved per QALY for THA (comparison of Group 1 to Group 3) USD 84 saved per QALY for TKA (comparison of Group 1 to Group 3) USD 330 saved per QALY for THA (comparison of Group 2 to Group 3) USD 438 saved per QALY for TKA (comparison of Group 2 to Group 3) |

| Hacek et al. [19] | 2008 | USA | Total joint | 1. Preoperative S. aureus screening and decolonization 2. Postintervention |

Retrospective | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, TKA—Hibiclens® (Regent Medical, Norcross, GA, USA) × 1 | PCR | USD 17,122 saved (cost of 4 SSIs in preintervention group) |

| Hassan et al. [22] | 2007 | UK | Elective and trauma orthopaedic | 1. MRSA-infected patients (nasal and perineal) | Retrospective | Mupirocin, triclosan | PCR | £384,000 (costs of MRSA SSIs in 10 patients) £261,000 (costs of MRSA screening and decolonization per year after PCR is set up) |

| Lee et al. [34] | 2010 | USA | Orthopaedic | 1. No screening or decolonization 2. Screen and decolonize MRSA-positive patients |

Model | Mupirocin × 10, 4% chlorhexidine gluconate × 10 | PCR and culture | Cost-effective to implement screening and decolonization protocol from the third-party payer perspective and hospital perspective (incremental cost-effectiveness ration < USD 6000 per QALY) |

| Nixon et al. [36] | 2006 | UK | Elective and trauma orthopaedic | 1. Preoperative S. aureus screening and decolonization 2. Postintervention |

Retrospective | Mupirocin × 5, triclosan × 5 | Culture | £3200 saved (cost of preventing one MRSA infection) |

| Rao et al. [42] | 2008 | USA | Total joint patients | 1. Preoperative S. aureus screening and decolonization 2. Postintervention |

Prospective | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | Culture | USD 231,741 saved (comparing hospital costs of preintervention patients with postintervention patients) |

| Rao et al. [43] | 2011 | USA | Total joint patients | 1. Preoperative S. aureus screening and decolonization 2. Postintervention |

Prospective | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine shower × 5 | Culture | USD 275,466 saved (comparing hospital costs of preintervention patients with postintervention patients) |

| Slover et al. [48] | 2011 | USA | Total joint and spine | 1. Total joint patients—no screening or decolonization; screen and decolonize S. aureus-positive patients 2. Spine patients—no screening or decolonization; screen and decolonize S. aureus-positive patients |

Model | Mupirocin × 5 | Culture | Total joint patients—cost savings if there is a 35% reduction in revision rate Spine patients—cost savings if there is a 10% reduction in revision rate (assumption—the cost of revision = the cost of a primary surgery) |

| van Rijen et al. [52] | 2012 | Netherlands | Orthopaedic and cardiothoracic | 1. Treatment arm—preoperative S. aureus screening and decolonization 2. Placebo arm—no S. aureus screening and no decolonization |

RCT | 2% mupirocin nasal ointment × 5, chlorhexidine gluconate soap × 5 | Not defined | Treatment arm: overall = €1911 savings compared with placebo, orthopaedics = €955 savings compared with placebo |

| Wassenberg et al. [55] | 2011 | Netherlands | Total joint and cardiothoracic | 1. All patients are treated 2. Only S. aureus positive patients were treated |

Model | 2% mupirocin × 5, chlorhexidine gluconate soap × 5 | Not defined | Treating all patients saves €7339, screening and treating patients saves €3330 |

MRSA = methicillin-resistant S. aureus; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year; RCT = randomized control trial; SSIs = surgical site infections.

For the studies based on patient data, cost savings was determined in one of the following methods: (1) the cost of implementing a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol compared with the cost of treating SSI in patients who did not undergo screening or decolonization; (2) the cost of treating SSIs from the screening and decolonization group compared with the cost of treating SSIs in the unscreened group; or (3) the comparison of hospital costs between the preintervention and interventions group (Table 3).

Results

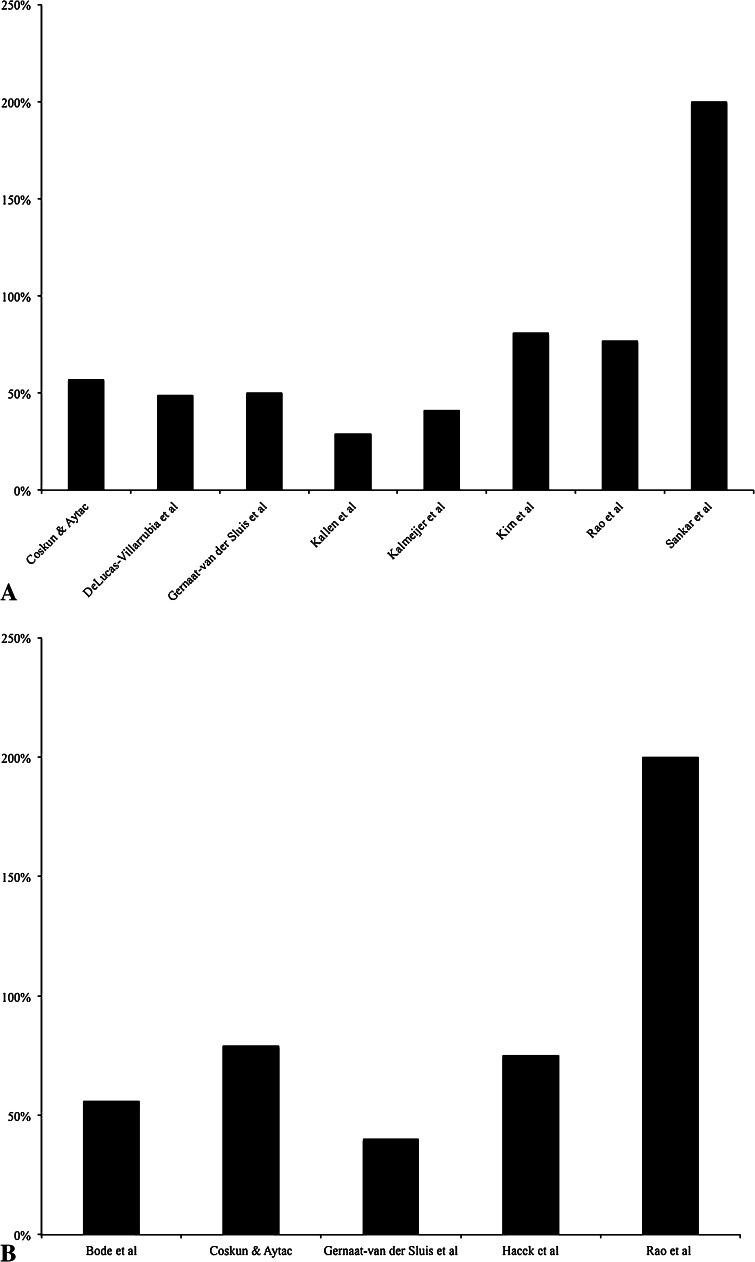

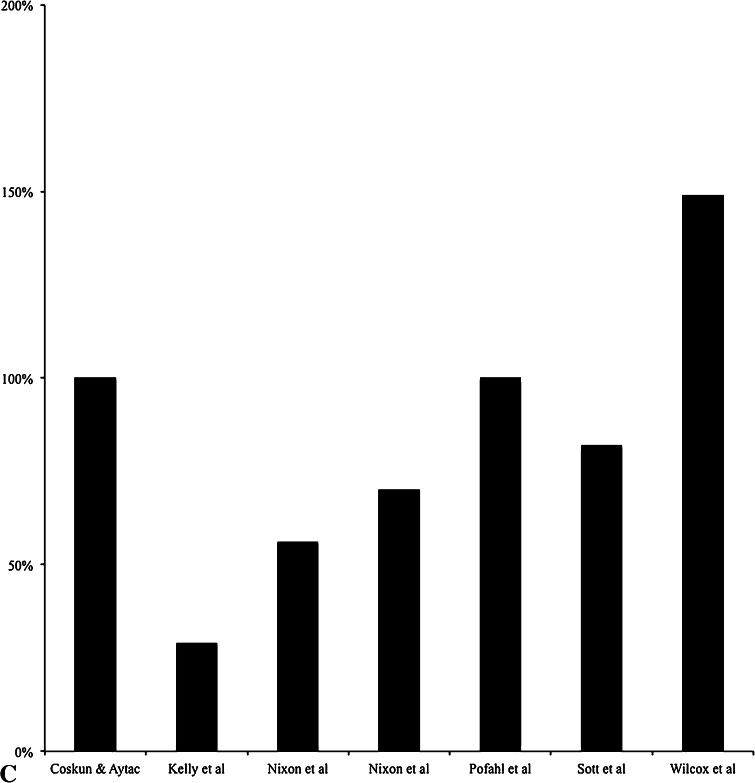

For the studies included in this systematic review, all 19 showed a reduction in SSIs (all SSIs, S. aureus SSIs, and/or MRSA SSIs) when a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol was used (Table 1). The reduction of overall SSIs ranged from 13% to 200% (Fig. 2A) [9, 11, 16, 20, 24, 26, 30, 43, 47], the reduction of S. aureus SSIs ranged from 40% to 200% (Fig. 2B) [5, 9, 16, 19, 42, 51], the reduction of MRSA SSIs ranged from 29% to 149% (Fig. 2C) [9, 29, 36, 40, 49, 57], and the reduction of wound complications was reported at 4% in one study [7]. Although all studies that were included showed reductions in SSIs with use of a decolonization protocol, not all reductions were statistically significant [20, 26, 29, 36, 49]. When evaluating the location of different SSIs, four studies showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention group and the nonintervention group regarding deep or superficial SSIs [26, 42, 43, 49]. However, one study [5] that decolonized only screen positive patients showed that the rate of deep SSIs decreased with use of a S. aureus decolonization protocol, and another study [29] that also decolonized only screen positive patients showed there was a significant decrease in deep SSIs with decolonization and moderate decrease in organ space or joint SSIs.

Fig. 2A–C.

The percentages are shown for (A) total SSI reduction, (B) S. aureus SSI reduction, and (C) MRSA SSI reduction after instituting a S. aureus decolonization protocol in orthopaedics.

S. aureus detection was performed by PCR in four studies [5, 19, 30, 40], culture in 13 studies [7, 9, 11, 16, 20, 24, 26, 29, 36, 42, 43, 49, 57], mixed methods of detection in one aggregate study [51], and unknown in one study [47]. Fifteen of the studies reported SSI reductions when only S. aureus-positive screened patients were decolonized, and eight studies [9, 11, 16, 20, 26, 36, 51, 57] reported decreases in SSIs when all patients were decolonized. Regarding the method of decolonization, six studies exclusively used mupirocin [9, 11, 16, 24, 26, 51], 10 used mupirocin and chlorhexidine [5, 7, 19, 20, 29, 30, 40, 42, 43, 49], and three used mupirocin and triclosan [36, 47, 57] (Table 2). The range of SSI reduction varied among groups; studies that used mupirocin showed only 29% to 57% reductions in total SSIs; studies that used mupirocin and chlorhexidine showed 13% to 81% reductions in total SSIs, 56% to 200% reductions in S. aureus SSIs, and 29% to 100% reductions in MRSA SSIs; and studies that used mupirocin and triclosan showed a 200% reduction in total SSIs and 56% to 149% reductions in MRSA SSIs.

The timing of administering the decolonization protocol also differed among studies. Most studies instituted the decolonization protocol at least 3 to 5 days before surgery [7, 9, 19, 20, 24, 29, 30, 36, 40, 42, 43, 47, 49], whereas some instituted decolonization the day before surgery [11, 16, 26, 57]. In only three studies [5, 29, 36] were patients decolonized on the day of admission, and in two of those studies [29, 36] orthopaedic trauma patients were exclusively decolonized in this manner, whereas the other study contained multiple surgical and surgical subspecialty patients [5]. In five studies [29, 30, 36, 47, 49] patients were reswabbed, and in four studies [29, 30, 47, 49] full decolonization of patients was done before the patients underwent surgery. Nixon et al. [36] found that nine of the 23 elective patients who were MRSA-colonized did not have eradication of infection. In all studies, contact precautions were instituted for patients who were MRSA-colonized. Additionally, antibiotic prophylaxis was changed for patients who were MRSA-positive in nine studies [7, 11, 20, 30, 36, 42, 43, 49, 57] with six studies changing to vancomycin [7, 20, 30, 42, 43, 57] and three changing to teicoplanin [11, 36, 49]. Three studies [5, 24, 29] did not mention the antibiotic prophylaxis that was used, one [40] allowed the surgeon to choose the antibiotic prophylaxis, one [19] differentiated the antibiotic prophylaxis by the procedure being performed (THA versus TKA), and the remaining five used first- or second-generation cephalosporins as antibiotic prophylaxis for all patients regardless of S. aureus colonization status.

For the costs of implementing a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol, all the economic models showed that implementing a S. aureus decolonization protocol was the economically preferred strategy. Two studies showed that decolonizing all patients instead of only colonized patients was the most cost-beneficial, in which USD 9969 was saved per life year gained when all patients were treated [10], and there was USD 330 saved per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for THA and USD 438 saved per QALY for TKA when all patients were decolonized [55]. Slover et al. [48] determined cost savings by calculating the reduction in revision rate that was needed to make up for the cost of implementing a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol; there needed to be a 35% reduction in the revision rate for patients having TKA and THA, and there needed to be a 10% reduction in revision rate for patients having spine surgery to make screening and decolonization cost-effective [48]. Lee et al. [34] showed that screening and decolonization was still the most cost-effective choice even when the following parameters were changed to make the protocol less desirable: a second body site was screened, there was a low prevalence of MRSA, and the decolonization success rates were low. Studies in orthopaedic patients [22, 36, 52] and those having total joint arthroplasty [19, 42, 43] also showed that implementing a S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol resulted in cost savings, because the cost of treating patients with SSIs with readmission was greater than the costs of instituting the screening and treatment protocol. Hassan et al. [22] evaluated the cost-effectiveness of instituting PCR as the method of detection for S. aureus colonization. Their economic analysis separated the cost of setting up PCR detection for the first year and performing S. aureus screening and decolonization in subsequent years. Although the cost of setting up the PCR was higher than subsequent years, all times were less costly than treating the extra SSIs that occurred without a screening and decolonization protocol. None of the studies or models analyzed different decolonization protocols.

Discussion

The causes of SSIs in orthopaedics are multifactorial, including surgical- and patient-related factors. Approximately 30% of the general population is colonized with S. aureus, and because S. aureus colonization is a risk factor for having an S. aureus (MSSA/MRSA) infection develop [31], it is important to find ways to reduce S. aureus (MSSA/MRSA) colonization before orthopaedic surgical procedures to decrease the risk of SSIs. One method is preoperative screening and decolonization of S. aureus-positive carriers. The purposes of our study were to determine (1) whether S. aureus screening and decolonization reduce SSIs in orthopaedic patients and (2) if implementing this protocol is cost-saving.

There were some limitations to our study regarding the literature and to our study approach. First, there was a lack of uniformity between studies (retrospective versus prospective), because each institution had different methods of detecting S. aureus and instituting decolonization protocols in specific patients (decolonization for patients colonized with S. aureus versus all patients). This made it unfeasible to calculate an aggregate statistical calculation. Second, by conducting the systematic review on only orthopaedic patients, we limited our literature search and may have excluded articles that are pertinent to S. aureus screening and decolonization but did not have MeSH terms specific to orthopaedics. Third, this systematic review was limited in that the results could not be stratified by type of surgery. Most studies combined elective orthopaedic patient populations (arthroplasty, spine, sports) together in the analysis, which made subgroup analyses for different cases impossible. Fourth, our systematic review was unable to elucidate if the infecting S. aureus strain was the same or different from the colonizing strain. Only one study in our systematic review [40] evaluated the strains of MRSA and found that of the seven patients who got MRSA SSIs, three were negative on screening and only two had the same USA 100 strain at screening and as a SSI. This finding is similar to that in the study by Berthelot et al. [4] who reported that of 77 patients who had S. aureus SSIs, only nine were positive for S. aureus at screening and six of the nine had the same strain at screening and as a SSI. Fifth, the studies included in this systematic review were unable to determine if different swab sites were more sensitive for detecting S. aureus colonization, because only three studies [29, 47, 49] reported swabbing at multiple sites and none of them correlated the swab site to the sensitivity of detection. Other studies conducted on nonorthopaedic patients have shown that swabbing multiple sites can increase the sensitivity of S. aureus detection [15, 33, 46]. Sixth, the rates of infection are generally low in orthopaedics; thus, there are few studies in the orthopaedic literature that have enough power to elucidate a statistically significant difference in interventions designed to decrease SSIs. The studies that were selected in this systematic review did show a decrease in SSI rate when comparing patients who did and did not undergo decolonization, but the differences were not always statistically significant. Finally, this study was limited to S. aureus screening and decolonization in orthopaedic patients and did not factor in other methods of decreasing SSI risk such as decolonizing orthopaedic staff members [12, 28, 41, 60] or ring fencing, which is creating a dedicated orthopaedic ward that segregates MRSA-positive patients to decrease the incidence of new MRSA infections [23].

Despite these limitations, our systematic review suggests that various S. aureus screening and decolonization protocols may reduce the risk of SSIs in select orthopaedic patients. This is the first systematic review specifically dedicated to orthopaedic patients, because other reviews have covered other surgical and medical patient populations [24, 45, 51]. Orthopaedic patients have two main adult patient populations: (1) emergency trauma patients and (2) elective orthopaedic patients who can undergo screening and decolonization before surgery. Nixon et al. [36] and Kelly et al. [29] performed the only two studies in our systematic review that screened emergency trauma patients on the day of admission; given the small number, there were not enough studies in this systematic review to compare the decolonization outcomes in elective versus emergency surgeries. When evaluating the different decolonization protocols, it was noted that there was a similar reduction in total SSIs when mupirocin alone or mupirocin and chlorhexidine were used in combination. Similarly, MRSA SSI reduction was similar for patients who used mupirocin and chlorhexidine for decolonization compared with using mupirocin and triclosan. However, given the heterogeneity of the studies in this review, it was not possible to reach a meaningful statistical conclusion about the SSI rate given the decolonization protocol used. The same was true for the antibiotic prophylaxis used. All nine studies [7, 11, 20, 30, 36, 42, 43, 49, 57] that changed antibiotic prophylaxis in MRSA-colonized patients reported SSI reductions, but the findings were similar for studies that did not institute a change in antibiotic prophylaxis based on colonization results. All these variations in a screening and decolonization protocol highlight that there is no uniform decolonization protocol and that implementing such a protocol can be difficult logistically. Following up on colonization results is time-consuming, regularly collecting data on SSI takes additional personnel [11], having dedicated personnel for screening patients may not be feasible [30], and separating colonized patients from other patients may not be possible [36]. Because of this, some studies have instituted universal decolonization [9, 11, 16, 20, 36, 57]. Universal decolonization may be an effective method for reducing SSIs in orthopaedic trauma patients, because there are no issues with ensuring compliance [6] and decolonization is performed immediately before surgery [1]. However, based on the results of our study, we cannot advocate for or against implementation of a universal decolonization protocol in orthopaedic patients because of the potential of having mupirocin resistance develop. Hacek et al. [19] screened for high-level mupirocin resistance by detecting the ileS-2 gene but did not comment about the level of mupirocin resistance. Wilcox et al. [57] performed the only other study included in this systematic review that evaluated mupirocin resistance and they found that there were low levels of mupirocin resistance (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] between 8 mg/L and 128 mg/L) that increased with the duration of the study, but there was no high-level mupirocin resistance (MIC > 128 mg/L). Another study, other than this systematic review, by Graber and Schwartz [17] evaluated mupirocin resistance and stated that failure of decolonization may indicate that current treatment regimens are becoming less effective for reducing SSIs and may be the result of increased mupirocin resistance. The study by Graber and Schwartz [17] also highlights the finding that decolonization may fail or recolonization with a different organism can occur in patients who undergo S. aureus screening and decolonization. Additionally, patients may have a SSI with a different strain of S. aureus (including MRSA)develop than what was treated at colonization [40]. Nixon et al. [36] reported that 39% of elective patients who screened positive for S. aureus experienced failure of eradication. Thus, other studies [29, 30, 47, 49] repeated testing throughout treatment to confirm patients were negative for S. aureus before proceeding with surgery. Although it is ideal to decolonize patients until S. aureus colonization has been eradicated, this protocol may be difficult to implement and may not be cost-effective, although this was not evaluated in any of the included studies.

In addition to the efficacy of S. aureus screening and decolonization to reduce SSI, economic model and patient studies showed that there is cost savings when this protocol is implemented in orthopaedic patients. However, similar to the conclusions stated previously, it was difficult to aggregate the studies in this systematic review to make overall conclusions about screening and decolonization protocols that should be implemented. We could not determine if a superficial, deep, or organ space/joint infection was associated with increased cost of treatment, because the three studies [19, 42, 43] that evaluated economic outcomes of the screening and decolonization protocol did not differentiate the types of SSI regarding costs. It also is difficult to determine the most efficacious way to detect S. aureus colonization, although Hassan et al. [22] reported that implementing PCR over culture can still save money when comparing the cost of treating SSIs in nonscreened patients with the cost of implementing the decolonization protocol. Additionally, PCR can provide results quicker than routine culture, but this was not studied from a cost-savings perspective.

The controversies highlighted here indicate there is additional room for research. Prospective randomized controlled studies examining different decolonization protocols on orthopaedic patients should be conducted to determine if specific S. aureus screening and decolonization protocols reduce SSIs. Standardization of decolonization protocols should be established to reduce SSIs. It is valuable to study other methods for preventing SSIs, especially because SSI reduction is one of the core measures in the Surgical Care Improvement Project. For now, our systematic review suggests that there is evidence in the literature to support preoperative screening and decolonization of S. aureus in orthopaedic patients to reduce SSIs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melissa Ratajeski MLIS, AHIP, RLAT, for assistance with the bibliographic file management software and Carola Van Eck MD, PhD, for language translation.

Appendix 1. Search strategies

PubMed

(((((((((((“Staphylococcus aureus”[Mesh] OR “Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus”[Mesh])) OR (“Staphylococcal Infections”[Mesh])) OR (“Surgical Wound Infection”[Mesh])) OR (“Methicillin Resistance”[Mesh])) OR ((“Methicillin”[Mesh]) AND “Drug Resistance, Microbial”[Mesh]))) OR ((((((((((MRSA[tiab])) OR (MSSA[tiab])) OR (((resistant[tiab] OR resistance[tiab] OR sensitive[tiab] OR susceptible[tiab])) AND (Methicillin[tiab]))) OR (Staphylococcal[tiab])) OR (Staphylococcus aureus[tiab])) OR (“S aureus”[tiab])) OR (“SSI”[tiab])) OR (“SSIs”[tiab])) OR (surgical site infect*[tiab])))) AND ((((((((((((((orthopedic[tiab] OR orthopedics[tiab])) OR (orthopaedic[tiab] OR orthopaedics[tiab])) OR (((joint[tiab] OR hip[tiab] OR knee[tiab])) AND (replacement[tiab] OR replacements[tiab]))) OR (tja[tiab])) OR (((((spine[tiab] OR spinal[tiab])) AND (surgery[tiab]))) OR (((spine[tiab] OR spinal[tiab])) AND (surgeries[tiab])))) OR (arthrodesis[tiab])) OR (arthroplasty[tiab] OR arthoplasties[tiab])) OR (spinal fusion*[tiab])) OR (fixation[tiab])) OR (prostheses[tiab])) OR (((fracture[tiab] OR fractures[tiab])) AND (((surgery[tiab])) OR (surgeries[tiab]))))) OR (((((((((((“Arthroplasty”[Mesh:noexp]) OR “Arthroplasty, Replacement”[Mesh])) OR ((“Fracture Fixation”[Mesh:noexp]) OR “Fracture Fixation, Internal”[Mesh])) OR (“Fractures, Bone/surgery”[Mesh])) OR (“Joints/surgery”[Mesh])) OR (“Musculoskeletal Diseases/surgery”[Mesh])) OR ((“Orthopedic Procedures”[Mesh:noexp]) OR “Arthrodesis”[Mesh])) OR (((((((“Wounds and Injuries/surgery”[Mesh:noexp]) OR “Spinal Injuries/surgery”[Mesh]) OR “Spinal Cord Injuries/surgery”[Mesh]) OR “Wound Infection/surgery”[Mesh]) OR “Dislocations/surgery”[Mesh:noexp]) OR “Hip Injuries/surgery”[Mesh]) OR “Leg Injuries/surgery”[Mesh:noexp]))) OR (“Orthopedics”[Mesh]))))) AND (((((((((((((((((“Administration, Intranasal”[Mesh])) OR (“Antibiotic Prophylaxis”[Mesh])) OR (“Carrier State”[Mesh])) OR (“Cefazolin”[Mesh])) OR (“Chlorhexidine”[Mesh])) OR (“Cross Infection/epidemiology”[Mesh] OR “Cross Infection/prevention and control”[Mesh])) OR (“Mass Screening”[Mesh])) OR (“Mupirocin”[Mesh])) OR (“Nose”[Mesh])) OR (“Vancomycin”[Mesh])) OR (“Triclosan”[Mesh])) OR (“Perioperative Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Preoperative Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Prevalence”[Mesh]))) OR ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((nares[tiab])) OR (carriage[tiab])) OR (carriers[tiab])) OR (colonization[tiab] OR colonisation[tiab])) OR (colonized[tiab] OR colonised[tiab])) OR (decolonized[tiab] OR decolonised[tiab])) OR (decolonization[tiab] OR decolonisation[tiab])) OR (eradication[tiab])) OR (“infection control”[tiab])) OR (intranasal[tiab] OR “intra nasal”[tiab])) OR (isolates[tiab])) OR (microbiology[tiab])) OR (nasal[tiab])) OR (noncarrier[tiab] OR noncarriers[tiab] OR “non carrier”[tiab] OR “non Carriers”[tiab])) OR (perioperative[tiab] OR “peri operative”[tiab])) OR (“post intervention”[tiab] OR postintervention[tiab])) OR (“pre intervention”[tiab] OR preintervention[tiab])) OR (preoperative[tiab] OR “pre operative”[tiab] OR preoperatively[tiab])) OR (prescreen*[tiab])) OR (rate decrease*[tiab])) OR (reduction[tiab] OR reductions[tiab])) OR (screened[tiab] OR screening[tiab])) OR (screen*[tiab])) OR (swab[tiab] OR swabs[tiab])) OR (uncolonized[tiab] OR uncolonised[tiab] OR “un colonized”[tiab] OR “un colonised”[tiab]))) OR (Vancomycin[tiab] OR cefazolin[tiab] OR Chlorhexidine[tiab] OR Mupirocin[tiab] OR Triclosan[tiab])))

The Cochrane Library (John Wiley & Sons)

[mh administration,intranasal] or [mh “Antibiotic Prophylaxis”] or [mh “Carrier State”] or [mh Cefazolin] or [mh Chlorhexidine] or [mh “Cross Infection”/EP,PC] or [mh “mass screening”] or [mh nose] or [mh Mupirocin] or [mh Vancomycin] or [mh Triclosan] or [mh “Perioperative Care”] or [mh “Preoperative Care”] or [mh Prevalence] OR “carriage”:ti,ab,kw or “carriers”:ti,ab,kw or “carrier”:ti,ab,kw or “colonization”:ti,ab,kw or “colonisation”:ti,ab,kw or “colonized”:ti,ab,kw or “colonised”:ti,ab,kw or “decolonized”:ti,ab,kw or “decolonised”:ti,ab,kw or “decolonization”:ti,ab,kw or “decolonisation”:ti,ab,kw or “eradication”:ti,ab,kw or edadicat*:ti,ab,kw or “infection control”:ti,ab,kw or “intranasal”:ti,ab,kw or “intra nasal”:ti,ab,kw or “isolates”:ti,ab,kw or “microbiology”:ti,ab,kw or “nasal”:ti,ab,kw or “noncarrier”:ti,ab,kw or “noncarriers”:ti,ab,kw or “non carrier”:ti,ab,kw or “non carriers”:ti,ab,kw or “perioperative”:ti,ab,kw or “peri operative”:ti,ab,kw or “post intervention”:ti,ab,kw or “postintervention”:ti,ab,kw or “pre intervention”:ti,ab,kw or “preintervention”:ti,ab,kw or “preoperative”:ti,ab,kw or “pre operative”:ti,ab,kw or “preoperatively”:ti,ab,kw or prescreen*:ti,ab,kw or rate decrease*:ti,ab,kw or “reduction”:ti,ab,kw or “reductions”:ti,ab,kw or “screened”:ti,ab,kw or “screening”:ti,ab,kw or screen*ti,ab,kw or “swab”:ti,ab,kw or “swabs”:ti,ab,kw or “uncolonized”:ti,ab,kw or “uncolonised”:ti,ab,kw or “un colonized”:ti,ab,kw or “un colonised”:ti,ab,kw or “Vancomycin”:ti,ab,kw or “cefazolin”:ti,ab,kw or “Chlorhexidine”:ti,ab,kw or “Mupirocin”:ti,ab,kw or “Triclosan”:ti,ab,kw

AND

“orthopedic*” or “orthopaedic*” or [mh ^”orthopedic procedures”] or [mh ^arthroplasty] or [mh arthroplasty,replacement] or [mh ^”fracture fixation”] or [mh “fracture fixation,internal”] or [mh fractures,bone/SU] or [mh joints/SU] or [mh orthopedics] or [mh “musculoskeletal diseases”/SU] or [mh arthrodesis] or “TJA” or (“joint” or “hip” or “knee”) and (replacement*) or (“arthroplasty” or “arthroplasties” or “arthrodesis” or spinal fusion*) or (“spine” or “spinal”) and (“surgery” or “surgeries”)

AND

[mh methicillin] and [mh “drug resistance,microbial”] or [mh ^”Staphylococcal Infections”] or [mh staphylococcus] or [mh “Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus”] or [mh “Staphylococcus aureus”] or [mh “surgical wound infection”] or “mrsa” or “mssa” or [mh “methicillin resistance”] or “s aureus” or “Staphylococcal” or “Staphylococcus aureus” or Surgical site infection* or “ssi” or “ssis”

EMBASE.com

‘coloni?ation’:ab,ti OR ‘coloni?ed’:ab,ti OR ‘decoloni?ation’:ab,ti OR ‘decoloni?ed’:ab,ti OR ‘uncoloni?ed’:ab,ti OR ‘carriage’:ab,ti OR ‘carriers’:ab,ti OR ‘noncarriers’:ab,ti OR ‘carrier’:ab,ti OR ‘noncarrier’:ab,ti OR edadicat*:ab,ti OR ‘infection control’:ab,ti OR ‘intranasal’:ab,ti OR ‘intra nasal’:ab,ti OR ‘microbiology’:ab,ti OR ‘nares’:ab,ti OR ‘nasal’:ab,ti OR ‘swab’:ab,ti OR ‘swabs’:ab,ti OR screen*:ab,ti OR prescreen*:ab,ti OR perioperativ*:ab,ti OR preoperativ*:ti OR ‘prophylaxis’:ab,ti OR ‘prophylactic’:ab,ti OR ‘rate decreased’:ab,ti OR intervent*:ti OR preintervent*:ab,ti OR ‘pre intervention’:ab,ti OR ‘bacterial colonization’/exp OR ‘bacterial strain’/de OR ‘bacterium carrier’/de OR ‘bacterium culture’/de OR ‘bacterium detection’/de OR ‘bacterium examination’/de OR ‘bacterium identification’/de OR ‘bacterium isolate’/de OR ‘practice guidelines’/exp OR ‘clinical protocols’/de OR ‘eradication therapy’/de OR ‘infection control’/de OR ‘infection prevention’/de OR ‘infection rate’/de OR ‘infection risk’/de OR ‘microbiological examination’/de OR ‘microbiology’/exp OR ‘nose’/exp OR ‘nose smear’/de OR ‘perioperative period’/de OR ‘preoperative care’/de OR ‘preoperative treatment’/de OR ‘prophylaxis’/de OR ‘antibiotic prophylaxis’/de OR ‘risk assessment’/de OR ‘screening’/de OR ‘mass screening’/de OR ‘screening test’/de OR ‘cefazolin’/exp OR ‘25953-19-9’:rn OR ‘cefazolin’:ab,ti OR ‘chlorhexidine’/exp OR ‘chlorhexidine’:ab,ti OR ‘3697-42-5’:rn OR ‘chlorhexidine gluconate’/exp OR ‘chlorhexidine gluconate’:ab,ti OR ‘18472-51-0’:rn OR ‘clindamycin’/exp OR ‘clindamycin’:ab,ti OR ‘fusidic acid’/exp OR ‘fusidic acid’:ab,ti OR ‘6990-06-3’:rn OR ‘clinisan’ OR ‘glycopeptide’/exp OR ‘glycopeptide’:ab,ti OR ‘polymyxin’/exp OR ‘polymyxin’:ab,ti OR ‘11081-39-3’:rn OR ‘triclosan’/exp OR ‘triclosan’:ab,ti OR ‘3380-34-5’:rn OR ‘vancomycin’/exp OR ‘vancomycin’:ab,ti OR ‘1404-90-6’:rn OR ‘aquasept’:tn OR ‘aquasept’:ab,ti OR ‘ancef’:tn OR ‘ancef’:ab,ti OR ‘bactroban’:tn OR ‘bactroban’:ab,ti OR ‘hibiclens’:tn OR ‘hibiclens’:ab,ti OR ‘mupirocin’:tn OR ‘mupirocin’:ab,ti

AND

‘fracture’/exp/dm_su OR ‘musculoskeletal disease’/exp/dm_su OR ‘bone graft’/de OR ‘foot surgery’/de OR ‘fractures fixation’ OR ‘hip arthroplasty’/de OR ‘joint prosthesis’/exp OR ‘joint surgery’/exp OR ‘orthopedic surgery’/de OR ‘orthopedics’/de OR ‘laminectomy’/de OR ‘spinal fusion’/exp OR ‘spine surgery’/de OR ‘prosthesis fixation’/de OR ‘femur fracture’/de OR ‘orthopedic’:ab,ti OR ‘orthopaedic’:ab,ti OR ‘orthopedics’:ab,ti OR ‘orthopaedics’:ab,ti OR ‘tja’:ab,ti OR ‘arthrodesis’:ab,ti OR ‘arthroplasty’:ab,ti OR ‘arthroplasties’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal fusion’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal fusions’:ab,ti OR ‘implant’/de OR ‘implantation’:de

OR

(‘fracture’:ab,ti OR ‘fractures’:ab,ti OR ‘spine’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal’:ab,ti) AND (‘surgery’:ab,ti OR ‘surgeries’:ab,ti)

AND

‘staphylococcus infection’/de OR ‘methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus infection’/de OR ‘methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus’/de OR ‘methicillin susceptible staphylococcus aureus’/de OR ‘penicillin resistance’/de OR ‘staphylococcus aureus’/de OR ‘antibiotic resistance’/de OR ‘antibiotic sensitivity’/de OR (‘meticillin’/de AND ‘drug resistance’/de) OR ‘mrsa’:ab,ti OR ‘mssa’:ab,ti OR ‘staphylococcal’:ab,ti OR ‘staphylococcus aureus’:ab,ti OR ‘s aureus’:ab,ti OR ‘surgical site infection’:ab,ti OR ‘surgical site infections’:ab,ti OR ‘ssi’:ab,ti OR ‘ssis’:ab,ti

OR

(‘resistant’:ab,ti OR ‘resistance’:ab,ti OR ‘sensitive’:ab,ti OR ‘susceptible’:ab,ti) AND (‘methicillin’:ab,ti OR ‘meticillin’:ab,ti)

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

References

- 1.Ammerlaan HS, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, Nouwen JL, Bonten MJ. Eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:922–930. doi: 10.1086/597291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DJ, Kaye KS, Chen LF, Schmader KE, Choi Y, Sloane R, Sexton DJ. Clinical and financial outcomes due to methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection: a multi-center matched outcomes study. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bengtsson S, Hambraeus A, Laurell G. Wound infections after surgery in a modern operating suite: clinical, bacteriological and epidemiological findings. J Hyg (Lond). 1979;83:41–57. doi: 10.1017/S002217240002581X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berthelot P, Grattard F, Cazorla C, Passot JP, Fayard JP, Meley R, Bejuy J, Farizon F, Pozzetto B, Lucht F. Is nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus the main acquisition pathway for surgical-site infection in orthopaedic surgery? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0867-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bode LG, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, Bogaers D, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Roosendaal R, Troelstra A, Box AT, Voss A, van der Tweel I, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Vos MC. Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:9–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey AR, Woodmansee SB, Crandall N, Tibert C, Fielding C, Mikolich DJ, Vezeridis MP, LaPlante KL. Low adherence to outpatient preoperative methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus decolonization therapy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:930–932. doi: 10.1086/661787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen AF, Chivukula S, Jacobs LJ, Tetreault MW, Lee JY. What is the prevalence of MRSA colonization in elective spine cases? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2684–2689. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Classen DC, Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Horn SD, Menlove RL, Burke JP. The timing of prophylactic administration of antibiotics and the risk of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:281–286. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coskun D, Aytac J. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus surgical-site infection rates after orthopaedic surgery after intranasal mupirocin ointment. J Hosp Infect. 2004;58:90–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courville XF, Tomek IM, Kirkland KB, Birhle M, Kantor SR, Finlayson SR. Cost-effectiveness of preoperative nasal mupirocin treatment in preventing surgical site infection in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:152–159. doi: 10.1086/663704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Lucas-Villarrubia JC, Lopez-Franco M, Granizo JJ, De Lucas-Garcia JC, Gomez-Barrena E. Strategy to control methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus post-operative infection in orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop. 2004;28:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s00264-003-0460-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edmundson SP, Hirpara KM, Bennett D. The effectiveness of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonisation screening in asymptomatic healthcare workers in an Irish orthopaedic unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1063–1066. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engemann JJ, Carmeli Y, Cosgrove SE, Fowler VG, Bronstein MZ, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, Sexton DJ, Kaye KS. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resistance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:592–598. doi: 10.1086/367653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans RP. Current concepts for clean air and total joint arthroplasty: laminar airflow and ultraviolet radiation: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:945–953. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forward KR. The value of multiple surveillance cultures for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:596–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gernaat-van Der Sluis AJ, Hoogenboom-Verdegaal AM, Edixhoven PJ, Spies-van Rooijen NH. Prophylactic mupirocin could reduce orthopedic wound infections: 1,044 patients treated with mupirocin compared with 1,260 historical controls. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:412–414. doi: 10.3109/17453679808999058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graber CJ, Schwartz BS. Failure of decolonization in patients with infections due to mupirocin-resistant strains of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:284. doi: 10.1086/527451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo JJ, Yang H, Qian H, Huang L, Guo Z, Tang T. The effects of different nutritional measurements on delayed wound healing after hip fracture in the elderly. J Surg Res. 2010;159:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacek DM, Robb WJ, Paule SM, Kudrna JC, Stamos VP, Peterson LR. Staphylococcus aureus nasal decolonization in joint replacement surgery reduces infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1349–1355. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadley S, Immerman I, Hutzler L, Slover J, Bosco J. Staphylococcus aureus decolonization protocol decreases surgical site infections for total joint replacement. Arthritis. 2010;2010:924518. doi: 10.1155/2010/924518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrop JS, Styliaras JC, Ooi YC, Radcliff KE, Vaccaro AR, Wu C. Contributing factors to surgical site infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:94–101. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-02-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan K, Koh C, Karunaratne D, Hughes C, Giles SN. Financial implications of plans to combat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in an orthopaedic department. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:668–671. doi: 10.1308/003588407X209400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston P, Norrish AR, Brammar T, Walton N, Hegarty TA, Coleman NP. Reducing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) patient exposure by infection control measures. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:123–125. doi: 10.1308/1478708051586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallen AJ, Wilson CT, Larson RJ. Perioperative intranasal mupirocin for the prevention of surgical-site infections: systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:916–922. doi: 10.1086/505453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalmeijer MD, Coertjens H, De Baere GA, Stuurman A, Van Belkum A, Kluytmans JA. Postoperative wound infections in orthopedic surgery: the effect of mupirocine nasal ointment. Pharmaceutisch Weekblad. 2001;136:730–731. doi: 10.1086/341025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalmeijer MD, Coertjens H, van Nieuwland-Bollen PM, Bogaers-Hofman D, de Baere GA, Stuurman A, Belkum A, Kluytmans JA. Surgical site infections in orthopedic surgery: the effect of mupirocin nasal ointment in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:353–358. doi: 10.1086/341025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalmeijer MD, van Nieuwland-Bollen E, Bogaers-Hofman D, de Baere GA. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus is a major risk factor for surgical-site infections in orthopedic surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:319–323. doi: 10.1086/501763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaminski A, Kammler J, Wick M, Muhr G, Kutscha-Lissberg F. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among hospital staff in a German trauma centre: a problem without a current solution? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:642–645. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.18756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly JC, O’Briain DE, Walls R, Lee SI, O’Rourke A, Mc Cabe JP. The role of pre-operative assessment and ringfencing of services in the control of methicillin resistant Staphlococcus aureus infection in orthopaedic patients. Surgeon. 2012;10:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DH, Spencer M, Davidson SM, Li L, Shaw JD, Gulczynski D, Hunter DJ, Martha JF, Miley GB, Parazin SJ, Dejoie P, Richmond JC. Institutional prescreening for detection and eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1820–1826. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauderdale KJ, Malone CL, Boles BR, Morcuende J, Horswill AR. Biofilm dispersal of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on orthopedic implant material. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:55–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lautenbach E, Nachamkin I, Hu B, Fishman NO, Tolomeo P, Prasad P, Bilker WB, Zaoutis TE. Surveillance cultures for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: diagnostic yield of anatomic sites and comparison of provider- and patient-collected samples. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:380–382. doi: 10.1086/596045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee BY, Wiringa AE, Bailey RR, Goyal V, Tsui B, Lewis GJ, Muder RR, Harrison LM. The economic effect of screening orthopedic surgery patients preoperatively for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:1130–1138. doi: 10.1086/656591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luna CM, Boyeras Navarro ID. Management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:178–184. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328336a23f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nixon M, Jackson B, Varghese P, Jenkins D, Taylor G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on orthopaedic wards: incidence, spread, mortality, cost and control. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:812–817. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noskin GA, Rubin RJ, Schentag JJ, Kluytmans J, Hedblom EC, Jacobson C, Smulders M, Gemmen E, Bharmal M. National trends in Staphylococcus aureus infection rates: impact on economic burden and mortality over a 6-year period (1998–2003) Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1132–1140. doi: 10.1086/522186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostrander RV, Botte MJ, Brage ME. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:980–985. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel N, Bagan B, Vadera S, Maltenfort MG, Deutsch H, Vaccaro AR, Harrop J, Sharan A, Ratliff JK. Obesity and spine surgery: relation to perioperative complications. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:291–297. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pofahl WE, Goettler CE, Ramsey KM, Cochran MK, Nobles DL, Rotondo MF. Active surveillance screening of MRSA and eradication of the carrier state decreases surgical-site infections caused by MRSA. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Portigliatti Barbos M, Mognetti B, Pecoraro S, Picco W, Veglio V. Decolonization of orthopedic surgical team S. aureus carriers: impact on surgical-site infections. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11:47–49. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao N, Cannella B, Crossett LS, Yates AJ, Jr, McGough R., 3rd A preoperative decolonization protocol for staphylococcus aureus prevents orthopaedic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1343–1348. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0225-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao N, Cannella BA, Crossett LS, Yates AJ, Jr, McGough RL, 3rd, Hamilton CW. Preoperative screening/decolonization for Staphylococcus aureus to prevent orthopedic surgical site infection: prospective cohort study with 2-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:1501–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:510–515. doi: 10.1086/501795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ro K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization: a review of the literature on prevention and eradication. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 2008;30(4):344–356. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohr U, Wilhelm M, Muhr G, Gatermann S. Qualitative and (semi)quantitative characterization of nasal and skin methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage of hospitalized patients. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2004;207:51–55. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sankar B, Hopgood P, Bell KM. The role of MRSA screening in joint-replacement surgery. Int Orthop. 2005;29:160–163. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slover J, Haas JP, Quirno M, Phillips MS, Bosco JA., 3rd Cost-effectiveness of a Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization program for high-risk orthopedic patients. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sott AH, Jones R, Davies S, Cumberland N. The value of pre-operative screening for MRSA in the reduction of sepsis in total hip replacement associated with MRSA: a prospective audit. Hip Int. 2001;11:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tacconelli E, De Angelis G. Pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:218–222. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283292666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Rijen M, Bonten M, Wenzel R, Kluytmans J. Mupirocin ointment for preventing Staphylococcus aureus infections in nasal carriers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD006216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006216.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Rijen MM, Bode LG, Baak DA, Kluytmans JA, Vos MC. Reduced costs for staphylococcus aureus carriers treated prophylactically with mupirocin and chlorhexidine in cardiothoracic and orthopaedic surgery. PloS One. 2012;7:e43065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vincent JL. Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet. 2003;361:2068–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wassenberg MW, de Wit GA, Bonten MJ. Cost-effectiveness of preoperative screening and eradication of staphylococcus aureus carriage. PloS One. 2011;6:e14815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilcox MH, Hall J, Pike H, Templeton PA, Fawley WN, Parnell P, Verity P. Use of perioperative mupirocin to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) orthopaedic surgical site infections. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54:196–201. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, Lavis JN, Ramkissoonsingh R, Arnold-Oatley AE, HSR Hedges team Optimal search strategies for detecting health services research studies in MEDLINE. CMAJ. 2004;171:1179–1185. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wimmer C, Gluch H, Franzreb M, Ogon M. Predisposing factors for infection in spine surgery: a survey of 850 spinal procedures. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zoabi M, Keness Y, Titler N, Bisharat N. Compliance of hospital staff with guidelines for the active surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its impact on rates of nosocomial MRSA bacteremia. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:740–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]