Abstract

Background

The direct anterior approach for THA allows implantation through an internervous plane without muscle detachment from bone. However, the classic longitudinal skin incision does not follow the anatomic skin creases and can result in scar widening. We therefore modified our incision technique to a short oblique skin incision following the anatomic skin crease of the groin.

Questions/purposes

We sought to determine whether (1) the oblique incision leads to improved scar results compared with the longitudinal incision, (2) functional and pain scores are similar between the two approaches, and (3) the new incision is safe with respect to complications, blood loss, implant position, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) symptoms.

Methods

Fifty-nine patients underwent THAs using either the classic (n = 33) or the new oblique incision (n = 26). At 6 months after surgery, we compared objective and subjective scar results, WOMAC, Oxford Hip and UCLA scores, blood loss, cup inclination, and the presence of LFCN symptoms between both groups.

Results

Objectively, the modified incision resulted in significantly shorter and narrower scars. Subjectively, patients in the modified incision group were substantially more satisfied with the aesthetic appearance. Functional and pain scores were similar. No complications occurred in either group. Blood loss and cup inclination did not differ between the two groups. There were no differences in LFCN symptoms.

Conclusions

In this series, which selected for thinner patients in the study group, the ‘bikini’ incision for an anterior approach THA led to improved scar cosmesis and was found to be safe in terms of blood loss, appropriate component placement, and risk for LFCN injury.

Level of Evidence

Level III, retrospective comparative study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The direct anterior approach (DAA) for THA was first described by Hueter and was popularized in France by Judet as early as since 1947 [7, 16]. This approach allows operating through an internervous and intervascular plane without muscle detachment from bone. In the past decade, such muscle-sparing approaches have gained attention. The DAA has potential advantages over other surgical approaches to the hip. It does not violate the integrity of lateral hip structures including the iliotibial band, greater trochanter, and hip abductor muscles, thereby potentially reducing the risk for painful THA [19]; postoperative pain after DAA has been reported to be reduced compared with the direct lateral approach [5]. Recovery of hip function and gait ability were more rapid after DAA compared with the miniposterior approach in one study [14]. Some authors suggest that the DAA does not require postoperative hip dislocation precautions [11, 15]. Rapid recovery after DAA also might limit postoperative loss of hip muscle force and mass [4]. Some advocates suggest that DAA may allow further broadening of indications for THA including one-stage bilateral THA [10] and can reduce hospitalization and treatment costs [3].

A frequently used argument against the DAA has been that it puts the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) at risk, and furthermore, the classic longitudinal skin incision might induce scar widening and subjective discomfort. Based on the experience in hip-preserving pelvic osteotomies, we adapted our incision technique to use a short oblique skin incision following the skin crease of the groin. The deep dissection then is performed similar to a W-plasty, an approach that previously has been used for appendectomy. Through this approach, the surgical window can be moved upward and downward as needed when preparing the acetabulum or the femur.

In this study, we describe the surgical technique for a DAA to the hip through a short-oblique ‘bikini’ incision. We also sought to determine whether (1) the oblique incision leads to improved scar results compared with the longitudinal incision, (2) functional and pain scores are similar, and (3) the new incision is safe with respect to complications, blood loss, implant position, and LFCN symptoms.

Surgical Technique

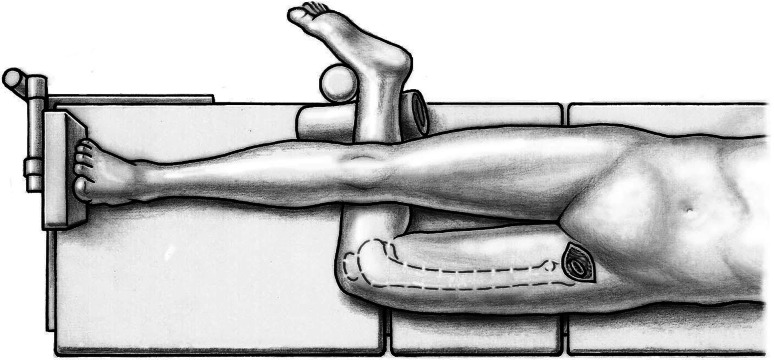

Fifty-nine patients underwent anterior THA using either the classic or the novel approach. All patients were operated on by one of the authors (ML). Patients were in the supine position and both legs were scrubbed and draped. We used standard operating tables with bendable stilts and the patients were positioned with the tip of the greater trochanter over the hinge (Fig. 1). A special table such as a fracture table is not required. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis was routinely administered with intravenous cefuroxime. The classic longitudinal skin incision starts approximately 2 cm laterally and distally from the anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS) and is extended toward the fibular head. The oblique incision is centered in the inguinal skin fold (Fig. 2), which can be identified by putting the hip into flexion, and extended approximately two-thirds laterally and one-third medially of the ASIS (Fig. 3). After palpation of the ASIS through the incision and identification of the tensor fascia lata (TFL) muscle, the superficial subcutaneous dissection is performed longitudinally, and the fascia of the TFL also is incised longitudinally the deeper dissection if performed within this fascial sheeth to prevent direct damage to the LCFN (Fig. 4). This deep dissection does not differ for either skin incision. The intervals between the sartorius and TFL and the rectus femoris and TFL, respectively, are prepared by blunt dissection. In this series, the ascending branches of the lateral femoral circumflex artery are ligated or coagulated (Fig. 5). The hip capsule is exposed anterolaterally mobilizing the gluteus minimus and TFL laterally and the iliocapsularis and rectus femoris medially.

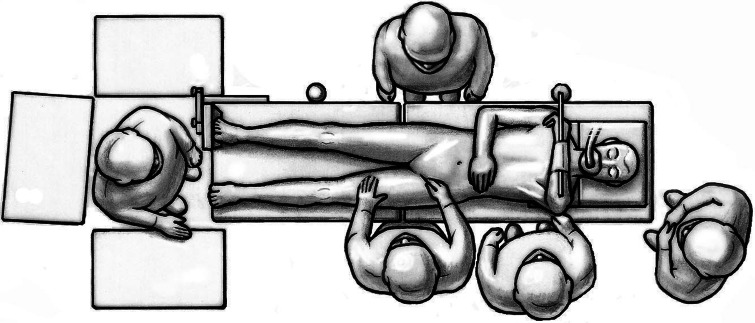

Fig. 1.

Surgery is performed with the patient in the supine position. The tip of the greater trochanter should be positioned over the hinge of the bendable stilts.

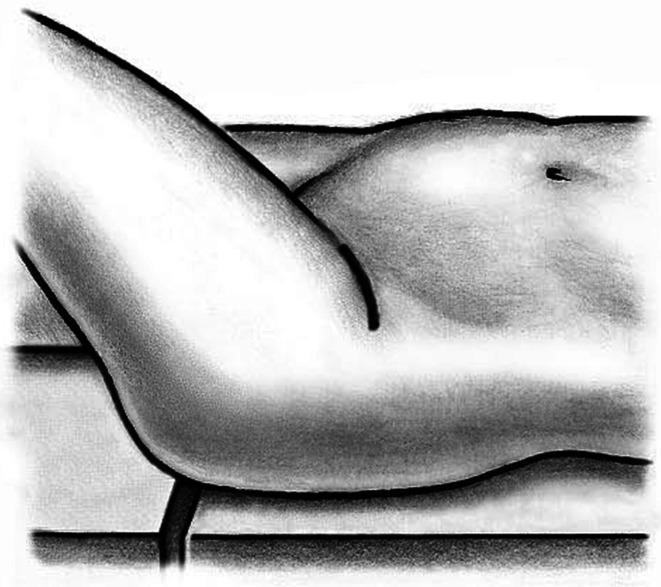

Fig. 2.

The oblique incision is centered in the inguinal skin fold and extended approximately two-thirds laterally and one-third medially of the ASIS.

Fig. 3.

The relationship of the oblique incision to the hip is shown.

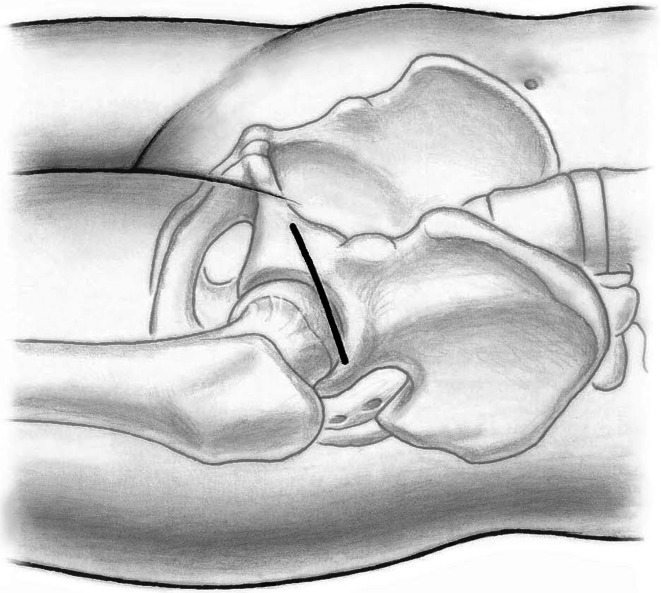

Fig. 4.

The fascia of the tensor fascia latae is dissected longitudinally on the lateral side of the ASIS to prevent direct damage to the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve.

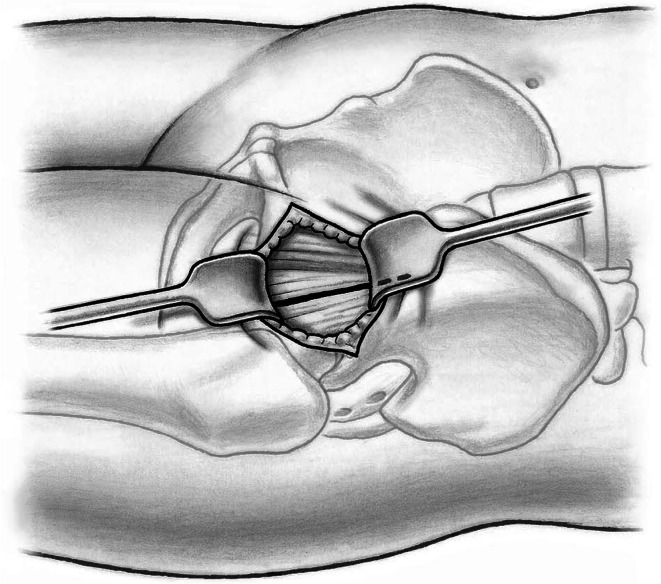

Fig. 5.

The course of the ascending branches of the lateral femoral circumflex artery indicate (i) the correct interval and (ii) the intertrochanteric line and can be ligated or coagulated.

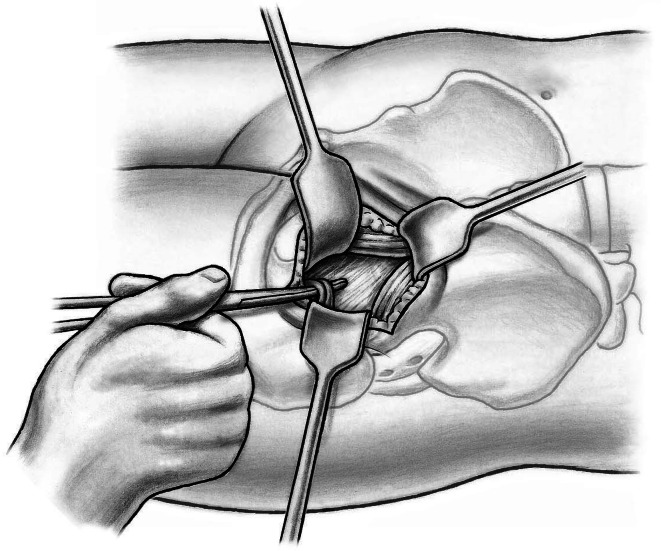

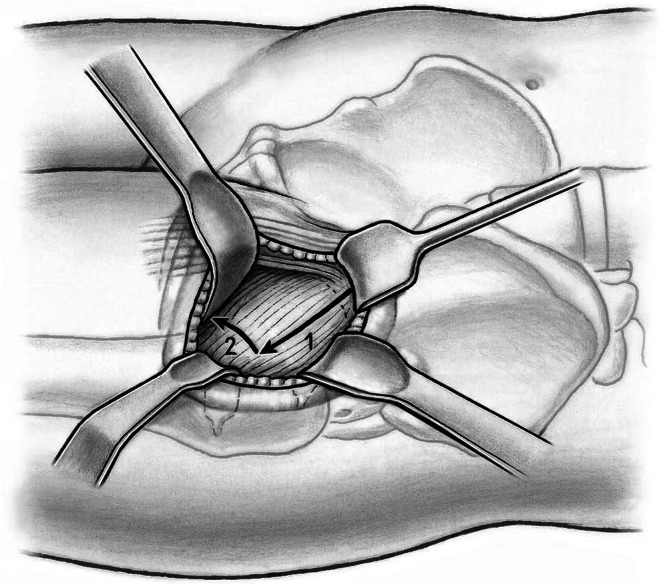

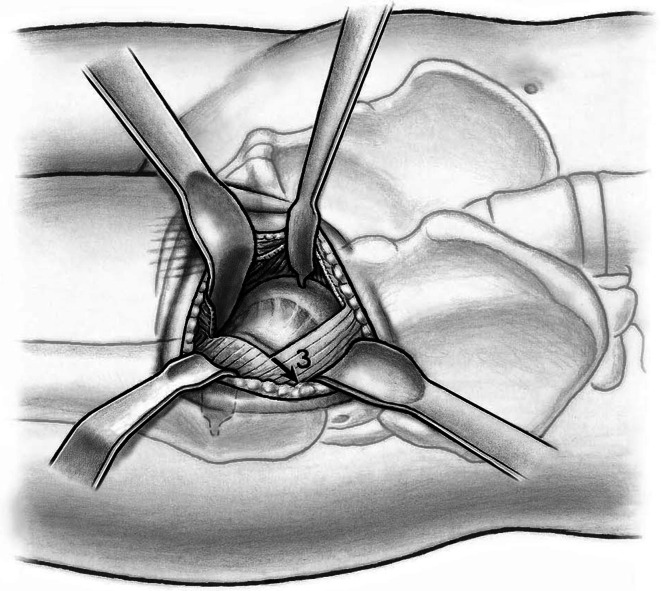

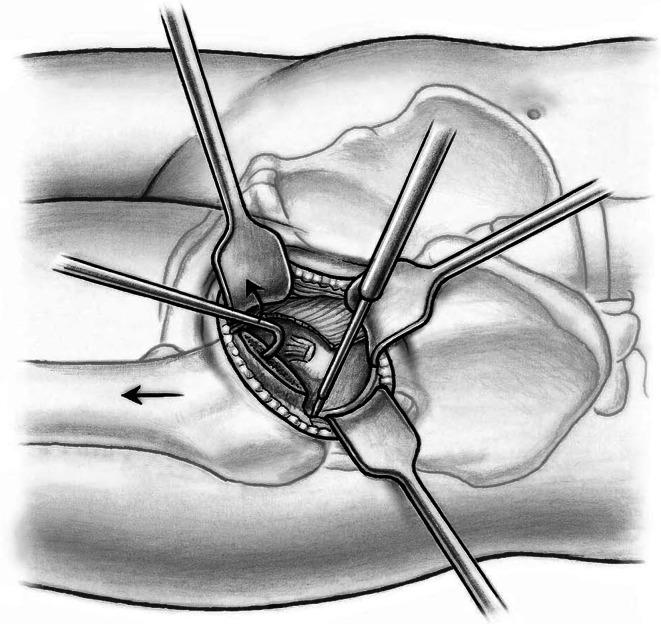

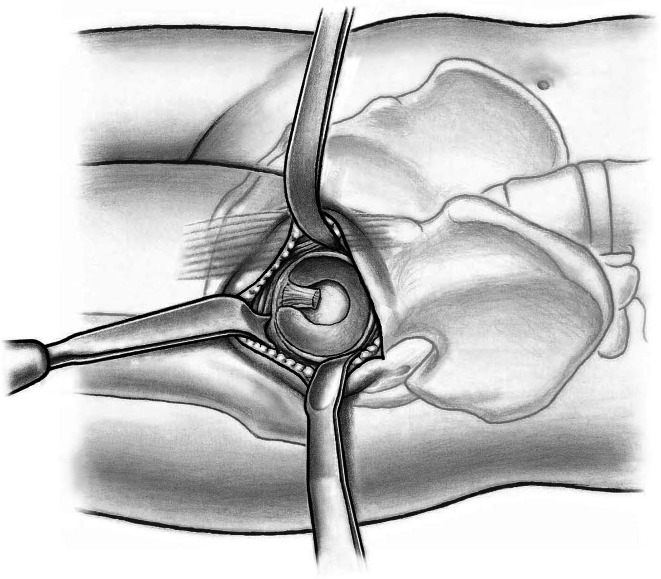

The shoulder and the tip of the greater trochanter then are identified. A blunt-angled Eva retractor (Subtilis series, Accuratus, Berne, Switzerland) is placed around the trochanteric shoulder, between the capsule and gluteus minimus, and an angled Hohmann retractor (Subtilis series, Accuratus, Berne, Switzerland) around the greater trochanter. An additional blunt Eva retractor is placed medially around the femoral neck between the capsule and rectus femoris underneath the iliocapsularis muscle (Fig. 6). Proximally, the reflected head of the rectus is identified and the joint capsule including the reflect head incised in an L-type fashion (inverse L-type for a right hip). To optimize intraarticular exposure, an 8-mm Hohmann retractor is placed on the femoral head, which tensions the capsule and allows better completion of the capsulotomy proximally and distally (Fig. 7). The blunt Eva retractors are repositioned intracapsularly. A corkscrew device is inserted into the femoral head to facilitate its removal later. At this point, we perform dislocation of the femoral head that results in disruption of the round ligament before the neck osteotomy. External rotation on the extended leg by the nurse combined with direct manipulation of the femoral head using a spoon inserted into the superior joint space and the corkscrew are helpful for controlled femoral head dislocation (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6.

A blunt-angled Eva retractor is placed around the trochanteric shoulder between the capsule and gluteus minimus and an angled Hohmann retractor around the greater trochanter. An additional blunt Eva retractor is placed medially around the femoral neck between the capsule and rectus femoris underneath the iliocapsularis muscle. An anterolateral capsulotomy including the reflect head of the rectus femoris toards the anterior trochanteric tubercle (1) and than towards the calcar femoris (2) can now be performed.

Fig. 7.

Placement of a small Hohmann retractor on the femoral head tensions the capsule and allows better completion of the capsulotomy proximally and distally.

Fig. 8.

Controlled femoral head dislocation can be achieved by direct manipulation of the femoral head using a spoon inserted into the superior joint space and the corkscrew under passive external rotation of the extended leg applied by the nurse.

After dislocation and reduction of the femoral head, the femoral neck cut is performed with the leg internally rotated to neutralize neck anteversion. The inferior border of the laterally placed blunt Eva retractor helps to avoid a neck cut that is too distal and may run into the greater trochanter. After completion of the neck cut, the head can be extracted easily using the previously inserted corkscrew. Although all the described steps are performed in full hip extension or 15° hip flexion, the leg is now brought into external rotation, still keeping the hip extended. This is achieved by flexing the knee and placing the heel of the operative leg on the lower contralateral leg (lazy figure-four position). This maneuver exposes the calcar region and the distal insertion of the anterolateral capsule can be removed. In stiff hips with capsular fibrosis, the capsule should be separated from the gluteus minimus and resected down to the level of the posterior acetabular wall to facilitate later femoral exposure. To complete mobilization of the proximal femur, the capsule on the inner side of the lateral trochanter is incised preceding this dissection dorsomedially until the obturator internus tendon is exposed. This release is performed under continuous traction using a blunt bone hook placed into the femoral medullary canal (Fig. 9). In some cases, gentle release of the piriformis muscle is advisable to achieve adequate elevation of the proximal femur.

Fig. 9.

For mobilization of the proximal femur, the capsule on the inner side of the lateral trochanter is incised preceding this dissection dorsomedially until the obturator internus tendon is exposed. This release is performed under continuous traction using a blunt bone hook placed into the femoral medullary canal.

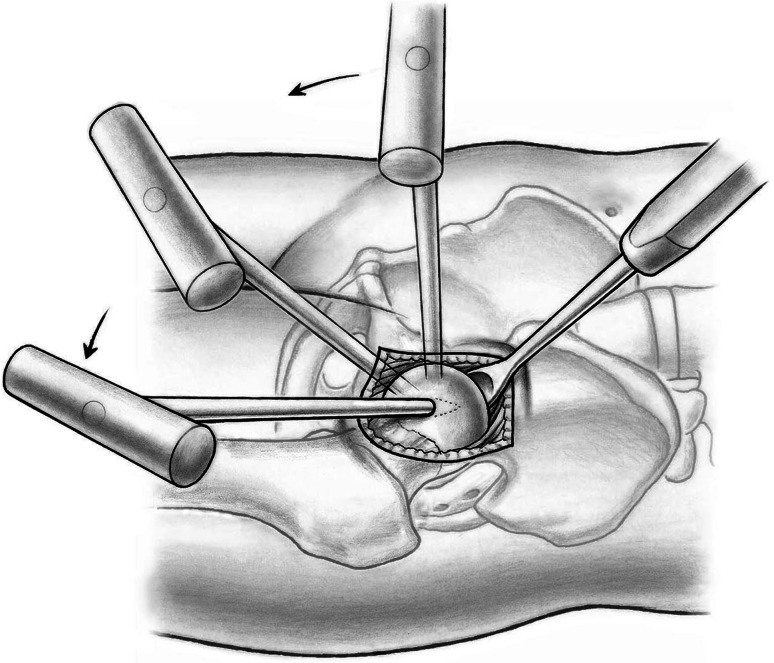

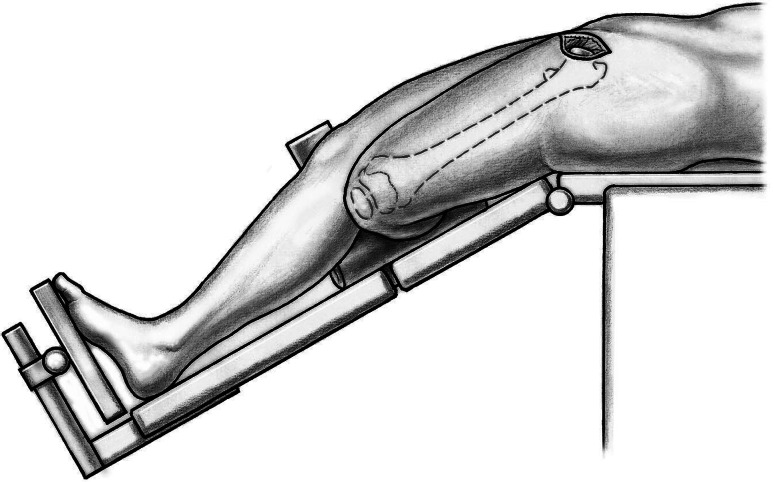

We prefer a femur-first technique. To expose the proximal femur for stem preparation, a special double-tipped retractor is placed around the greater trochanter, the leg is adducted and externally rotated (figure-four position in adduction with the surgically treated leg now underneath the untreated leg, Fig. 10), and the stilt of the table is bent to lower the patient’s legs (hyperextension), opening up the hip (Fig. 11). Placement of a bent Hohmann rectractor medially around the proximal femur sometimes further improves observation. Double-offset instruments are recommended for femoral preparation (broaching or reaming) to avoid soft tissue damage (Fig. 12).

Fig. 10.

The figure-four position in adduction with the surgically treated leg underneath the untreated one before femoral preparation is shown.

Fig. 11.

Bending the stilt to lower the patient’s legs (hyperextension) opens up the hip facilitating preparation of the proximal femur.

Fig. 12.

A special double-tipped retractor is placed behind the greater trochanter and a small Hohmann retractor medially. Femoral reaming can now be performed. Double offset instruments are advisable to avoid soft tissue damage.

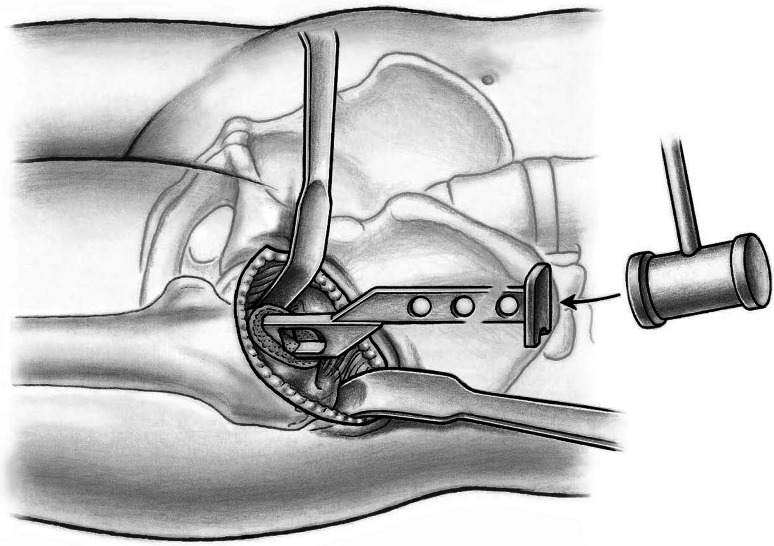

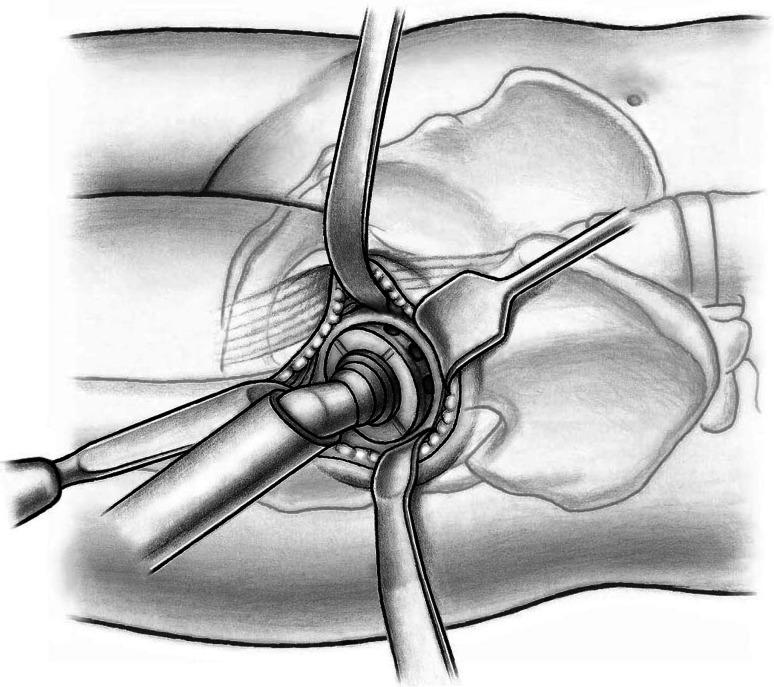

To expose the acetabulum, the leg is repositioned in 10° hip flexion release tension of the hip flexors, and two bent Hohmann retractors are inserted initially, one into the acetabular fossa and another around the posterior wall. A Müller retractor (Subtilis series, Accuratus, Berne, Switzerland) is placed around the inferior horn of the posterior acetabular wall. Now the entire acetabulum is exposed. Soft tissues are resected off the acetabular rim (labrum, hypertrophic synovial tissue) and the acetabular fossa (pulvinar). Any central osteophyte (double fond) should be removed to identify the true acetabular floor. We now replace the retractor in the acetabular notch by a short curved easy-rider hook placed on the proximal part of the anterior wall close to the ASIS (Fig. 13). This probably is the most dangerous surgical step. The retractor should be placed from the inside of the joint underneath the capsule. Perforating the rectus femoris will endanger the neurovascular structures medially. The acetabulum can now be prepared and reamed as usual down to the true acetabular floor (Fig. 14). Similar to the femoral preparation, the use of offset reamers is recommended to avoid soft tissue stress. After insertion of trial components, the femur first technique allows for control of acetabular version and abduction, best when a 135° femoral component is used. Moreover, soft tissue tension, hip stability in extension and flexion, and leg length can be controlled. Thereafter, first the definite acetabular component and then the femoral component are inserted. Again, a physical assessment for length and stability can be performed. For closure, we use running sutures for the TFL fascia, interrupted sutures for the subcutaneous tissue, and a resorbable intracutaneous suture for the skin. Patients are mobilized on the first postoperative day with weightbearing as tolerated. We recommend the use of crutches for approximately 2 weeks.

Fig. 13.

Placement of a Müller retractor around the inferior horn of the posterior acetabular wall, a Hohmann retractor around the posterior wall, and a short curved easy-rider hook on the proximal part of the anterior wall close to the ASIS allows complete observation of the acetabulum.

Fig. 14.

With offset reamers the acetabular preparation is performed oriented medially towards the acetabular floor.

Patients and Methods

Between January and April 2010, 59 patients with end-stage hip osteoarthritis were enrolled for THA with DAA using either the classic incision (n = 33) or the novel oblique skin crease incision (n = 26). Because we conducted this study early after introducing the novel approach, we did not perform randomization. Therefore, the two cohorts differed in terms of gender and BMI; we tended to enroll slimmer females in the novel approach group (Table 1). During the study period, the first author (ML) performed all THAs via the DAA except for four hip resurfacing arthroplasties and three revision arthroplasties in which a posterior approach was used. All patients were followed for 6 months after surgery and no patient was lost to followup. At 6 months, the patients completed a questionnaire related to satisfaction with the scar using a numeric rating scale (from 0 = very dissatisfied to 10 = very satisfied). Lengths and widths of scars were measured by a clinician (MF) not involved in the surgery. Functional and pain outcomes were determined by the WOMAC what is best and worst for all of the scores, Oxford Hip Score, and the UCLA activity scale [12, 13, 18]. To determine the safety of the new incision technique, all intraoperative and postoperative complications were assessed and the operating time (skin incision to skin closure), blood loss, and cup inclination were compared between both groups. The presence and area size of any hypoesthesia in the distribution of the LFCN was assessed by a needle test (MF).

Table 1.

Demographic variables of the study cohorts

| Demographics | Classic incision | New incision | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) | 30 | 77 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 66 | 70 | 0.263 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 | 25 | 0.078 |

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 15; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were compared using unpaired t-tests. Unless otherwise stated, all results are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

At 6 months, subjective ratings related to the scar were excellent in both groups. The novel oblique incision (Fig. 15) achieved better ratings for overall aesthetic appearance and width (Table 2). Objectively, the new incision resulted in narrower and shorter scars (Table 2).

Fig. 15.

A photograph of a narrow scar in the skin crease of the groin 6 months after a bikini incision THA is shown.

Table 2.

Outcome variables of the study cohorts

| Parameter | Classic incision | New incision | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | |||

| Duration (minutes) | 73 | 75 | 0.444 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 413 | 316 | 0.105 |

| Cup inclination | 43° | 44° | 0.682 |

| Scar subjective | |||

| Aesthetic appearance | 7.6 | 9.4 | 0.007 |

| Length (cm) | 9.1 | 9.4 | 0.536 |

| Width (mm) | 8.9 | 9.8 | 0.041 |

| Dysesthesia (%) | 23 | 16 | 0.250 |

| Scar objective | |||

| Length (cm) | 9.8 | 8.7 | 0.009 |

| Width (mm) | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.002 |

| Hypesthesia (%) | 60.6 | 61.5 | 0.942 |

| Area size (mm2) | 71.6 | 79.6 | 0.663 |

| Functional scores | |||

| WOMAC pain | 13.0 | 6.3 | 0.124 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 14.8 | 14.9 | 0.976 |

| WOMAC function | 9.1 | 11.0 | 0.567 |

| Oxford Hip Score | 19.4 | 16.9 | 0.240 |

| UCLA activity scale | 6.5 | 6.2 | 0.516 |

The WOMAC, Oxford Hip, and UCLA activity scale scores were similar between the two approaches (Table 2).

There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications in either group. The operating time, blood loss, and cup inclination did not differ between both groups (Table 2). With the numbers available, there was no difference between the groups in terms of dysesthesia around the scars (23% in the longitudinal incision group, 16% in the bikini incision group; p = 0.25). Some objective hypoesthesia in the distribution of the LCFN was present in approximately 60% of both groups with the objective needle test (Table 2). There was no classic meralgia paresthetica. Neither functional nor pain-related scores differed between patients with or without LCFN hypoesthesia or dysesthesia.

Discussion

The DAA for THA has been used with increasing frequency during the last decade. Nevertheless, the LCFN is at risk in a DAA THA regardless of the skin incision chosen, and the classic longitudinal skin incision does not follow the anatomic cleavage lines, which can be associated with scar widening. This study evaluated a modified skin incision for a DAA THA, which follows the oblique skin crease in the groin cleavage line; we determined that through this approach cosmetic results improved, components can be positioned accurately, and the surgery performed safely.

Before interpreting the current results, several limitations have to be considered. The comparison between both incision techniques was conducted at a very early time after starting the new technique, and the patients therefore were not randomized. When beginning with this new incision, we tended to select slimmer patients and more females (Table 1), because we considered observation to be easier in such cases. We recommend that surgeons learning the approach begin by selecting slimmer patients or females until the familiarity with this new technique has been established. Although there clearly was selection bias during the period of this study, we now are able to treat most patients undergoing DAA THA with this bikini incision. Other limitations are related to the small sample size and the short followup, as are typical in surgical technique articles; what we present here, in essence, is a feasibility study with preliminary results.

The present data confirm our hypothesis that the new bikini incision led to improved cosmesis of the incision, subjectively and objectively. The width of the scar was decreased by more than half with the new approach, suggesting that the oblique incision better respects the anatomic creases of the skin.

Clinically, the results at 6 months were excellent in both groups and we found no differences in functional and pain scores. Furthermore, no intraoperative or postoperative complications occurred in either group, and with both incision techniques, similarly good component placement were achieved; there were no differences in cup inclination angles between the groups. However, concerns regarding increased complication rates with the DAA for THA have been raised [8]. There is an obvious learning curve when beginning with the anterior approach, which seems to involve the first 40 to 100 cases [9, 17]. The absence of complications in our patients therefore might be attributed to the surgeon’s experience (ML); he was beyond his learning curve when this study was conducted. We also acknowledge that the number of complications might increase with inclusion of larger cohorts and longer followup. We thus do not recommend the use of the presented oblique incision until the surgeon is familiar with the classic DAA. Regarding the potential risk of calcar or trochanteric femoral fractures [8], we consider sufficient release and mobilization of the proximal femur as key to avoiding these complications. However, if they occur, cerclage wires can be put around the greater trochanter and around the femur down to the level of the lesser trochanter or slightly below when using the oblique incision. Any fractures passing beyond this level should be addressed using a separate approach. Although we have no defined cutoff BMI value, we recommend the longitudinal incision for morbidly obese patients in which soft tissues largely overhang the groin. We also have no strict contraindications for the DAA in general. Very stiff and contracted hips or posttraumatic cases in which posterior hardware has to be removed might be better treated using different approaches.

Another issue with the DAA is direct or indirect injury to the LCFN. We found an incidence of subjective LCFN dysesthesia in approximately 20% and objective hypoesthesia in approximately 60% of the patients. These values compare favorably with those reported previously [1, 6], and according to Bhargava et al. [1], symptoms in many of these patients improve with time. We believe that LCFN problems mainly are related to a reversible neurapraxia of the LCFN as a result of traction caused by the retractors rather than to an irreversible dissection injury. LCFN injuries also occur frequently after periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) when an anterior Smith-Petersen approach is used; dysesthesia has been reported in as much as 30% of these cases [2]. Biedermann et al. [2] considered LCFN dysesthesia a minor complication after PAO, but they found patients with LCFN dysesthesia to have worse WOMAC scores than those without. In contrast, pain levels and functional outcomes (WOMAC, Oxford Hip Score, UCLA score) at 6 months were similar in patients with or without LCFN hypoesthesia in our series. Therefore, LCFN injuries seem to occur frequently after THA using the DAA regardless of whether a longitudinal or bikini incision is used. Although some considered found LFCN injuries to be a major complication, in our series, they were not severe.

Our modified bikini incision technique for the DAA for THA leads to improved objective and subjective results related to cosmesis of the scar, is safe in terms of complications and appropriate component placement, and does not increase the risk for the LFCN. A larger randomized trial comparing the bikini incision with the classic DAA or other approaches would be a desirable future investigation.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Schulthess Clinic, Zurich, Switzerland.

Contributor Information

Michael Leunig, Email: michael.leunig@kws.ch.

Florian D. Naal, Email: florian.naal@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bhargava T, Goytia RN, Jones LC, Hungerford MW. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve impairment after direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2010;33:472. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100526-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32:611–617. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0372-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bremer AK, Kalberer F, Pfirrmann CW, Dora C. Soft-tissue changes in hip abductor muscles and tendons after total hip replacement: comparison between the direct anterior and the transgluteal approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:886–889. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.25058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark BC. In vivo alterations in skeletal muscle form and function after disuse atrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1869–1875. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a645a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goebel S, Steinert AF, Schillinger J, Eulert J, Broscheit J, Rudert M, Nöth U. Reduced postoperative pain in total hip arthroplasty after minimal-invasive anterior approach. Int Orthop. 2012;36:491–498. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulding K, Beaulé PE, Kim PR, Fazekas A. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neurapraxia after anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2397–2404. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito Y, Matsushita I, Watanabe H, Kimura T. Anatomic mapping of short external rotators shows the limit of their preservation during total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1690–1695. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2266-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jewett BA, Collis DK. High complication rate with anterior total hip arthroplasties on a fracture table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:503–507. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masonis J, Thompson C, Odum S. Safe and accurate: learning the direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2008;31:pii:orthosupersite.com/view.asp?rID=37187. [PubMed]

- 10.Mast NH, Muñoz M, Matta J. Simultaneous bilateral supine anterior approach total hip arthroplasty: evaluation of early complications and short-term rehabilitation. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:115–124. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194309.70518.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Leunig M. Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:958–965. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naal FD, Sieverding M, Impellizzeri FM, von Knoch F, Mannion AF, Leunig M. Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted German Oxford hip score. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:952–957. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0457-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakata K, Nishikawa M, Yamamoto K, Hirota S, Yoshikawa H. A clinical comparative study of the direct anterior with mini-posterior approach: two consecutive series. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachbauer F. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: anterior approach. Orthopade. 2006;35:723–724, 726–729. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Rachbauer F, Kain MS, Leunig M. The history of the anterior approach to the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seng BE, Berend KR, Ajluni AF, Lombardi AV., Jr Anterior-supine minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: defining the learning curve. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stucki G, Meier D, Stucki S, Michel BA, Tyndall AG, Dick W, Theiler R. [Evaluation of a German version of WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities) Arthrosis Index][in German] Z Rheumatol. 1996;55:40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakovlev AE, Resch BE, Karasev SA. Treatment of intractable hip pain after THA and GTB using peripheral nerve field stimulation: a case series. WMJ. 2010;109:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]