Summary

African-Americans and Hispanics are disproportionally affected by disasters. We evaluated differences in the use and completion of a web-based mental health intervention, Disaster Recovery Web (DRW), by White, African-American and Hispanic adults in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike. Approximately one year after the hurricane, a telephone survey was carried out with adults from Galveston and Chambers counties. A total of 1249 adults participated in the survey (80% White, 14% African-American and 6% Hispanic). Mental health and mental health service utilization were assessed. Whites were more likely to have previously used the Internet to obtain general health information than African-Americans or Hispanics (P < 0.001). A logistic regression was used to identify differences in the use of the Internet intervention after controlling for covariates. There were no differences in rates of non-use and dropout attrition between Whites, African-Americans and Hispanics. Thus the findings suggest that web-based mental health interventions can be used to reach African-American, Hispanic and White adults at similar rates after a disaster.

Introduction

African-Americans and Hispanics are disproportionally affected by natural disasters and have been shown in some studies to experience greater levels of post-disaster mental health distress.1,2. However, access to high quality care is often limited in the aftermath of a disaster.3 Web-based interventions have the potential to overcome significant barriers.4,5 Internet based, or web delivered, interventions can provide education in an easily accessible, non-threatening format that patients can review at a time that is most relevant to their needs.4 However, Internet use and home broadband access is lower amongst African-Americans and Hispanics when compared to Whites.6 Despite the majority of African-Americans (77%) and Hispanics (75%) having access to the Internet, these groups are less likely to use the web to obtain health related information.7 It is unclear whether African-Americans and Hispanics are likely to use and complete brief mental health oriented web-based interventions.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate differences in the use and completion of a web based mental health intervention, Disaster Recovery Web (DRW), by White, African-American and Hispanic adults in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike. Hurricane Ike was a strong Category 2 cyclone that hit Galveston, Texas in 2008 and resulted in 84 deaths.8 We hypothesized that African-Americans and Hispanics would be less likely to begin and complete the intervention.

Methods

Approximately one year after Hurricane Ike, a telephone survey was carried out of adults from Galveston and Chambers counties using random-digit-dialling. Data were weighted by age to be consistent with the estimated populations in these counties. Eligible participants were 18 years or older, had a landline telephone, lived in the area during the hurricane, and reported having Internet access at home. After an eligible household was contacted, interviewers used the most recent birthday method to select a participant. This method is technically equivalent or superior to other respondent selection techniques and places less burden on the participant.9 The interviewer asks to speak to the person with the most recent birthday, thus avoiding the need to obtain a list of all potential respondents in the house and make a random selection. Informed consent was obtained by telephone. The gender balance in the sample was monitored during recruitment. On evenings where the gender distribution was unbalanced, interviewers asked to speak to members of the opposite gender in the household with the most recent birthday. The overall cooperation rate calculated according to American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) industry standards (i.e. [completed interviews + screen outs] divided by [completed interviews + screen outs + refusals]), was 50%. The study was approved by the appropriate ethics committees.

Participants

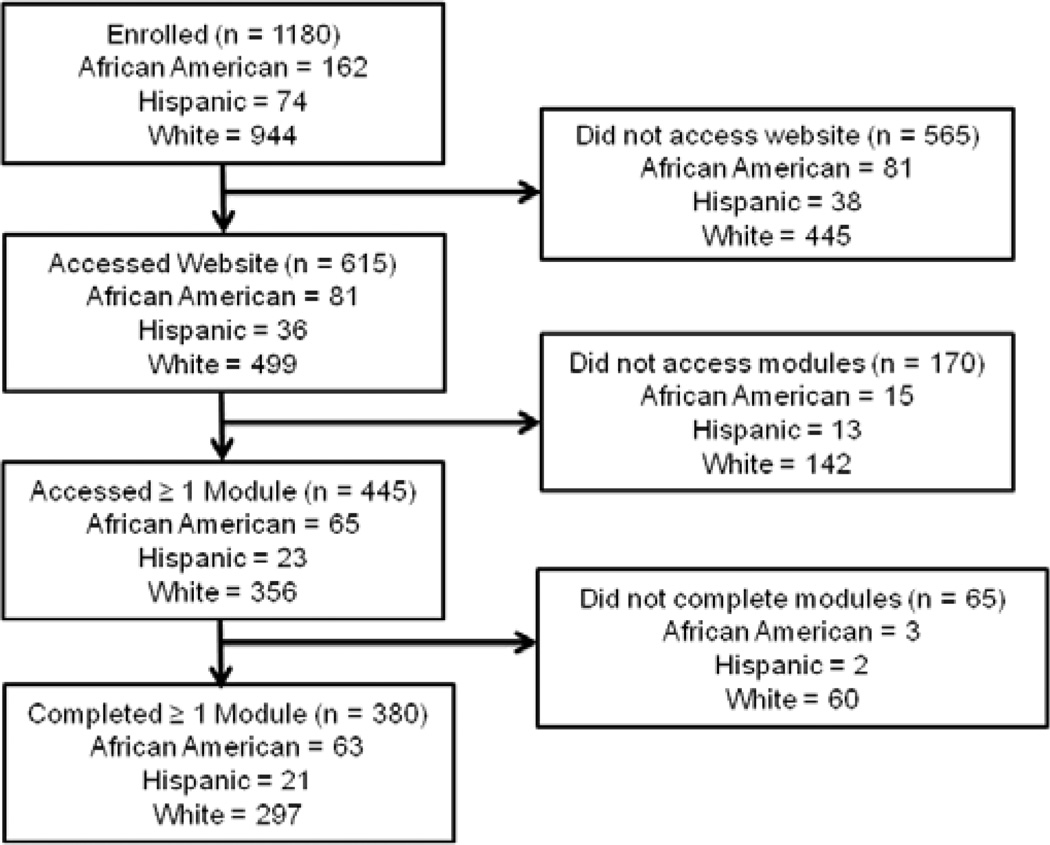

A total of 1249 adults participated in the survey. Only participants who self-identified as White (n = 944, 80%), African-American (n = 162, 14%) or Hispanic (n = 74, 6%) were included in the study. Participants who self-identified as bi-racial (n = 22) were excluded. The sample was representative of the broader area with regard to income and ethnic background, with the exception of those of Hispanic origin. The reduced proportion of the latter was probably due to the interview and website only being available in English.

The mean age of the sample was greater than that of the area and so all analyses were weighted for age. The average age for the sample was 46 years (SD = 17) and subjects were equally distributed across genders. All participants reported having good Internet access from their home. They had slightly higher than average education, with 79% having received some college education. The majority of participants reported an annual household income of $60,000–80,000.

Measures

A structured telephone interview was used to assess demographics (age, gender and income), impact of exposure to Hurricane Ike, mental health symptoms and service utilization.

Mental health symptoms were assessed with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version10 and the Depressed Mood Scale-10 (CES-D). The PSTD checklist is a 17-item instrument that assesses DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. Each item consists of five response options (possible scores 17–85). Internal consistency for the present sample was excellent (α = 0.92). The CESD-10 was developed from the original 20-item CES-D measure, which has been validated in various populations. Internal consistency for the present sample was good (α = 0.85).

Mental health service utilization was assessed in two ways. First, participants were asked about their help-seeking behaviour and their use of the Internet for obtaining health related information unrelated to their experience with Hurricane Ike. They were asked if they had considered using mental health services in the past, whether they had used the Internet to obtain information about health matters, and whether they had used the Internet to obtain information about mental health issues specifically. They were also asked if they had ever received care for an emotional problem from a doctor or mental health professional.

Procedures

Computer-assisted structured telephone interviews were conducted by a survey research company. Supervisors conducted random checks of data entry accuracy and interviewers’ adherence to the assessment procedures. The average interview lasted 21 min and respondents were compensated for their participation in the study. At the end of the baseline interview, participants were introduced to the web phase of the study and invited to access the DRW website. They were told, “The website was designed specifically for people who have experienced a disaster and you might find it to be useful.” They were provided with the website address and a password for access for the four-month period between the baseline and follow-up telephone interviews.

The structure of the web-based intervention has been described in detail elsewhere.11 Briefly, participants completed a brief mental health screen to determine which treatment modules, if any, would be most relevant. The screening was designed to be inclusive so that participants with sub-clinical symptom levels would be directed to the intervention modules. Such participants were then provided with access to the relevant modules. Modules were designed to address symptoms of depression, PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, alcohol abuse, marijuana abuse and cigarette smoking.

Attrition was divided into three categories. Non-use attrition was defined as participants who completed the baseline telephone interview but did not access the website. Dropout attrition was divided into two categories: access attrition and completion attrition. Access attrition was classified as not having accessed a module after completing the website screens. Completion attrition was defined as failing to complete a module after having accessed a module.

Results

A total of 5536 households were contacted for the interview. A total of 2403 failed to meet the inclusion criteria, 1768 refused to complete the interview, and 116 were not interviewed because the quota for their area had been met. The demographic information of the participants is summarised in Table 1. Those in the White sample were significantly older than those in the African-American and the Hispanic samples (P < 0.001), although this pattern is consistent with that of the US Census. African-Americans reported greater levels of PTSD symptoms (P < 0.001) and depression symptoms (P < 0.001) than Whites and Hispanics. There were also differences in prior help-seeking behaviour. Whites were more likely to have used the Internet to obtain general health information than African-Americans or Hispanics (P < 0.001). There were non-significant differences amongst reported rates of using the Internet to obtain mental health information. Whites were more likely than African-Americans and Hispanics to have considered mental health services (P = 0.01), received mental health services from a mental health provider (P < 0.001), or received mental health services from a non-psychiatric physician (P = 0.001). These variables were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic information for participants. Values in parentheses are percentages, except where indicated

| White (n=944) | African-American (n = 162) |

Hispanic (n = 74) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD)* | 48 (17) | 40 (18) | 38 (15) |

| Male | 484 (51) | 79 (49) | 36 (49) |

| Education | |||

| Completed high school | 164 (17) | 63 (38) | 26 (35) |

| Some college | 344 (37) | 52 (32) | 30 (41) |

| Completed college | 274 (29) | 25 (15) | 13 (18) |

| Graduate work | 162 (17) | 24 (15) | 5 (7) |

| Income, $ per year | |||

| <40,000 | 168 (18) | 69 (42) | 15 (20) |

| 40,000–80,000 | 251 (27) | 36 (22) | 27 (37) |

| >80,000 | 396 (42) | 34 (21) | 19 (10) |

| Missing | 128 (14) | 23 (14) | 12 (17) |

| Prior health service use | |||

| Considered mental health services* | 348 (37) | 42 (26) | 21 (29) |

| Searched online for general health information* | 650 (69) | 67 (42) | 32 (43) |

| Searched online for mental health information | 277 (29) | 45 (28) | 12 (17) |

| Received help from a mental health professional for emotional distress* | 236 (25) | 20 (13) | 13 (17) |

| Received help from a doctor for emotional distress* | 228 (24) | 19 (12) | 13 (17) |

| Mental health symptoms | |||

| PCL-C score (SD)* | 21.9 (4.1) | 27.5 (7.1) | 22.6 (4.3) |

| CES-D 10 score (SD)* | 4.10 (5.35) | 7.05 (6.55) | 4.28 (5.38) |

P = 0.01

A logistic regression was used to identify differences in non-use attrition of the Internet intervention amongst Whites, African-Americans and Hispanics after controlling for covariates (Tables 2 and 3). There were no differences in rates of non-use attrition between Whites and African-Americans (OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.64–1.43) and Whites and Hispanics (OR = 1.31, 95% CI 0.76–2.29). There were no differences in rates of dropout attrition for access of modules among Whites and African-Americans (OR = 1.45, 95% CI 0.63–3.29) and Whites and Hispanics (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.32–1.74). Finally, there were no differences in the number of modules completed for Whites and African-Americans (OR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.89–1.36) and Whites and Hispanics (OR = 1.22, 95% CI 0.86–1.67). These findings suggest that there were no differences in rates of non-use and dropout attrition between Whites, African-Americans and Hispanics. A power analysis suggested that the sample sizes of the present study (Non-use/use = 1180 to Completer/non-completer = 380) were sufficient to detect a medium OR (OR = 1.80) at power from 0.99 to 0.88 and a small OR (OR = 1.50) at power from 0.96 to 0.62, respectively.

Table 2.

Results of a logistic regression examining the differences in rates of non-use attrition between Whites, African-Americans and Hispanics

| Odds ratio |

95% confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|

| African-Americans | 0.96 | 0.64–1.43 |

| Hispanics | 1.31 | 0.76–2.29 |

| Male gender | 0.93 | 0.71–1.21 |

| Income | 1.05 | 0.97–1.13 |

| Education | 1.05 | 0.934–1.18 |

| Age | 0.99* | 0.98–0.99 |

| PCL-C | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 |

| CES-D 10 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 |

| Considered mental health services | 1.5 | 0.96–2.36 |

| Searched online for general health information | 1.51* | 1.12–2.04 |

| Searched online for mental health information | 1.07 | 0.77–1.49 |

| Received help from a mental health professional for emotional distress | 1.21 | 0.73–2.03 |

| Received help from a doctor for emotional distress | 0.58* | 0.35–0.96 |

P = 0.01

Table 3.

Results of a logistic regression assessing dropout attrition and completion

| Accessed ≥1 module | Module completion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |

| African-Americans | 1.45 | 0.63 | 3.29 | 1.10 | 0.89 | 1.36 |

| Hispanics | 0.74 | 0.32 | 1.74 | 1.22 | 0.86 | 1.67 |

| Male gender | 0.45** | 0.29 | 0.70 | 0.86* | 0.75 | 0.98 |

| Income | 0.96 | 0.83 | 1.11 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 1.01 |

| Education | 1.04 | 0.85 | 1.27 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.11 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99** | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| PCL-C | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 |

| CES-D 10 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| Considered mental health services | 0.82 | 0.41 | 1.62 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 1.10 |

| Searched online for general health information | 1.69** | 1.03 | 2.78 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.40 |

| Searched online for mental health information | 1.13 | 0.66 | 1.95 | 1.18* | 1.01 | 1.37 |

| Received help from a mental health professional for emotional distress | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.57 | 1.30* | 1.01 | 1.70 |

| Received help from a doctor for emotional distress | 2.17 | 0.86 | 5.43 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 1.14 |

| Number of positive screens | 3.18** | 2.36 | 4.29 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.06 |

P = 0.05

P = 0.01

Discussion

The present findings suggested that rates of non-use attrition, access attrition and completion attrition did not differ between African-Americans, Hispanics and Whites. These findings were obtained in a sample that had similar demographic characteristics and mental health symptoms to other disaster samples.1 Consistent with previous research, fewer African-Americans and Hispanics reported having previously used the Internet to search for general health information, had previously considered using mental health services, had received help from a mental health professional, or had received help from a doctor for emotional distress. Nevertheless, the present findings suggested that Whites, African-Americans and Hispanics were equally likely to access, use, and complete the disaster mental health web-based intervention of the present study. These findings provide preliminary support for the potential for web-based interventions to reduce mental health disparities in disaster-affected populations.

There are several proposed mechanisms to explain the similar rates of engagement and completion between African-Americans, Hispanics and Whites. Web-based approaches address several of the predisposing factors that prevent participation, including reducing stigma and allowing participants greater autonomy in their progression through the intervention. However, the present study did not assess mechanisms of use that are relevant across cultures (e.g. stigma, stereotype fears). Future research focusing on the identification of these mechanisms in the use of web-based approaches would greatly inform recruitment and retention efforts of multicultural groups for clinical and technology-focused research.

Web based approaches can also facilitate the enabling factors of availability and accessibility, which have limited African-American and Hispanic participation in mental health research and treatment previously.12 Future work should examine rates of use in disaster-affected samples through the use of portable Internet devices such as smartphones or tablet computers. Portable devices have the added benefit of being more widely available and are more commonly used to access the Internet by African-Americans and Hispanics.13

The present study had several limitations. First, although participants were recruited via random-digit dialling, interviews were only conducted with people living in homes with landline telephones and home Internet access. Although, approximately three-quarters of US households have Internet access and a landline telephone,14 participants in the study may not have been representative of people living below the national poverty level. Indeed, the sample had a higher average income than other samples used in disaster research. Although this is consistent with the location from which they were sampled, in conjunction with the household Internet access inclusion criterion for the study, it reduces the generalizability of the findings to low income groups with limited Internet access. Second, interviews were conducted only in English and the results may not be relevant to non-English speaking people affected by disaster. However, over 95% of Hispanic adults in Galveston and Chambers counties reported speaking English very well at the time of the interview.

In addition, participants received email reminders to complete the intervention content, which may have influenced their completion rates. Information about the frequency of these reminders was not available for analysis. Participants were also compensated for their access to the website, which may have increased access rates.15 However, it should be noted that all participants were offered the same amount of compensation for use of the website and previous work has suggested that financial incentives are insufficient to overcome the attitudinal barriers that multicultural groups face when considering participation in research.16 Therefore, it is unclear whether compensation had a differential effect on access and use in different ethnic groups. Finally, the intervention was administered to participants one year after the disaster. The effects of a disaster have been shown to decrease in the following year.17 The rates of access and use of the website may therefore have been less because many of the participants had recovered naturally.

Overall, the findings of the present study suggest that web-based mental health interventions can be used to reach African-American, Hispanic and White adults at similar rates.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R34 MH77149. Dr Price was supported by T32 MH018869. Dr Davidson was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH081056–03S2. Dr Ruggiero was supported by P60 MH082598. Dr Andrews was supported by the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (NCRR/NIH UL1 RR029882).

References

- 1.Perilla JL, Norris FH, Lavizzo EA. Ethnicity, culture, and disaster response: identifying and explaining ethnic differences in PTSD six months after Hurricane Andrew. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2002;21:20–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins AO, Zinzow HM, Amstadter AB, Danielson CK, Ruggiero KJ. Marginalized populations. Mental health consquences of disasters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amstadter AB, Broman-Fulks J, Zinzow H, Ruggiero KJ, Cercone J. Internet-based interventions for traumatic stress-related mental health problems: a review and suggestion for future research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christopher Gibbons M. Use of health information technology among racial and ethnic underserved communities. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2011;8:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pew Internet and American Life Project. Demographics of Internet Users. [last checked 26 August 2012]; See http://pewinternet.org/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Whos-Online.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohall AT, Nye A, Moon-Howard J, et al. Computer use, internet access, and online health searching among Harlem adults. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25:325–333. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090325-QUAN-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hurricane Ike rapid needs assessment - Houston, Texas, September 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1066–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaziano C. Comparative analysis of within-household respondent selection techniques. Public Opin Q. 2005;69:124–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weathers F, Litz B, Huska J, Keane T. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-C) for DSM-IV. Boston: National Center for PTSD; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Paul LA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention using random-digit-dial recruitment: the Disaster Recovery Web project. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox S. Mobile Health 2010. [last checked 26 August 2012]; See http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Mobile-Health-2010.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2010. [last checked 26 August 2012];Center for Disease Control. 2010 See http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless201012.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins GD, Mitra A, Gupta N, Shaw JD. Are financial incentives related to performance? A meta-analytic review of empirical research. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83:777–787. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loftin WA, Barnett SK, Bunn PS, Sullivan P. Recruitment and retention of rural African Americans in diabetes research: lessons learned. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:251–259. doi: 10.1177/0145721705275517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pietrzak RH, Tracy M, Galea S, et al. Resilience in the face of disaster: prevalence and longitudinal course of mental disorders following Hurricane Ike. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]