Abstract

This study determined whether time-domain P3 amplitude and time-frequency principal component (TF-PC) reductions are present in adulthood (age 29) when participants have largely passed through the age of heaviest substance misuse. Participants were assessed from age 17 through 29 for lifetime externalizing (EXT) disorders. EEG comparisons from three topographic regions were examined for P3 amplitude and TF-PCs at delta and theta frequency ranges. Significant P3 amplitude reductions were found in those with EXT for both regional and site-Pz analyses, with stronger effects observed the greater the EXT comorbidity. Reductions were also observed in all eight TF-PCs extracted, with a delta component yielding frontal effects not apparent in the time-domain. Overall, results suggest that these brain measures continue, at age 29, to provide effective indices of EXT that potentially tap a neural substrate related to behavioral disinhibition.

Keywords: P3 amplitude, time-frequency principal components, disinhibitory behavioral disorders, substance dependence, externalizing psychopathology

Introduction

Research shows that measures associated with the P3 event-related potential provide reliable indices of externalizing (or EXT) psychopathology which is characterized by disorders and actions indicative of behavioral disinhibition that disrupt the ability to inhibit socially-inappropriate or even proscribed behaviors (Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008). Numerous investigations in the time-domain demonstrate that P3 amplitude reduction (P3AR) is associated with disorders marked by behavioral disinhibition (see meta-analysis by Euser, Arends, Evans, Greaves-Lord, Huizink, & Franken, 2011 and review by Iacono et al., 2008). More recent studies have also decomposed the P3 into time-frequency components indicating that they have potential to provide further insight into the nature of the P3-EXT relationship (Gilmore, Malone, Bernat, & Iacono, 2010). Furthermore, results of multivariate modeling demonstrate that both P3 amplitude and a TF component showed significant phenotypic and genetic correlation with a latent EXT factor suggesting that these P3-related measures have potential utility as multivariate endophenotypes for EXT (Gilmore, Malone, & Iacono, 2010). However, much of this important work was assessed using adolescent and emerging adult samples with P3 typically measured from a single posterior site (site-Pz), thus leaving unclear the nature of these associations through the end of early adulthood when the cumulative effects of substance use might be more detectable, and when brain development is more likely complete.

The present study investigated the P3-related response using both time-domain and time-frequency measures in a community sample of 29-year-old men (n = 303) who have been evaluated since age 17 for the presence of lifetime EXT disorders. Brain activity was assessed across the scalp using a high-density electrode array in addition to analyses at the traditional site-Pz electrode.

Numerous studies have linked time-domain P3AR to externalizing disorders such as Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; see review by Barry, Johnstone, & Clarke, 2003; Yoon, Iacono, Malone, Bernat, & McGue, 2008), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD; Baving, Rellum, Laucht, & Schmidt, 2006), Conduct Disorder (CD; Bauer & Hesselbrock, 1999), and Adult Antisocial Behavior (AAB, the symptoms of antisocial personality disorder that onset after age 15; Iacono, Carlson, Malone, & McGue, 2002). Furthermore, P3AR is noted in subjects with substance dependence, including alcohol (Malone, Iacono, & McGue, 2001; Porjesz & Begleiter, 1996, 1998), nicotine (Anokhin et al., 2000), cannabis (Solowij, Michie, & Fox, 1991), and cocaine (Bauer, 2001b; Biggins, MacKay, Clark, & Fein, 1997). Iacono et al. (2002) provided a conceptual nexus for these studies by demonstrating that P3AR may reflect a broader index of EXT that taps a neural substrate underlying behavioral disinhibition. This study of adolescents is particularly relevant to the current investigation because it uses the same visual task and community sample in a broad evaluation of EXT. Other work on this sample demonstrated that the comorbidity among EXT disorders is accounted for by a hierarchical latent EXT factor (Krueger et al., 2002) that is transmissible within families (Hicks, Krueger, Iacono, McGue, & Patrick, 2004), and furthermore that P3 amplitude constitutes a facet on this factor (Patrick et al., 2006), with which it shares genetic influences (Hicks et al., 2007).

However, the association between P3AR and EXT may depend on developmental context. For instance, visual P3 amplitude has been shown to undergo normative decreases over adolescence through early adulthood (Courchesne, 1978; Hill et al., 1999), potentially qualifying the utility of this candidate endophenotype by developmental stage (Hill, Steinhauer, Locke-Wellman, & Ulrich, 2009). Using the same sample of males and ERP task as in the current investigation, Carlson and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that P3 amplitude displays significant linear decreases across ages 17, 20, and 23, thus confirming previous cross-sectional observations with the ERP paradigm used in the present study (Katsanis, Iacono, & McGue, 1996). The topographic expression of P3 may also shift frontally during late adolescence (Bauer & Hesselbrock, 2001, 2003), with frontal P3-AR putatively providing more effective indices for EXT in older subjects with alcohol dependence (Kamarajan et al., 2005), ASPD (Bauer, O’Connor, & Hesselbrock, 1994; Costa et al., 2000), ASPD and comorbid cocaine dependence (Bauer, 2001a), as well as subjects at high familial risk for alcohol dependence (Hada, Porjesz, Chorlian, Begleiter, & Polich, 2001). These frontal P3 findings, however, raise an issue regarding the possible cumulative effects of substance exposure since the frontal cortex may be particularly vulnerable to such effects (Moselhy, Georgiou, & Kahn, 2001; Oscar-Berman & Marinkovic, 2003; Rogers & Robbins, 2001) especially as subjects age (Sullivan, Deshmukh, Desmond, Lim, & Pfefferbaum, 2000).

Advances in analytic methods and data reduction techniques allow for extraction of event-related time-frequency principal components (TF-PCs) from ERP data that potentially captures more relevant EXT-related variance than the time-domain P3 amplitude alone (Gilmore et al., 2010). EXT research has focused predominantly on delta (0–3 Hz) and theta (3–7 Hz) since these frequencies dominate the ERP time course, thus contributing substantially to the composition of the P3 waveform (Basar-Eroglu, Basar, Demiralp, & Schurmann, 1992; Bernat, Malone, Williams, Patrick, & Iacono, 2007; Demiralp, Ademoglu, Istefanopulos, Basar-Eroglu, & Basar, 2001; Jones et al., 2006). Generally, EXT investigations find that these TF-PCs are significantly reduced in EXT cases versus controls. For instance, Kamarajan et al. (2004) found that alcoholics displayed frontal power reductions in the delta and theta frequencies while Jones et al. (2006) found that alcoholics exhibited delta and frontal theta reductions that were topographically more widespread. In another study directly relevant to the current investigation, Gilmore et al. (2010) extended the Iacono et al. (2002) time-domain findings by evaluating associations between various TF-PCs and EXT in the same community sample of 17-year-old males. Decompositions at site-Pz revealed five TF-PCs with one particular delta component discriminating all EXT groups from controls. Collectively, these studies support the notion that P3-related measures offer multiple effective brain markers related to EXT.

The present study reflects an extension of the Iacono et al. (2002) and Gilmore et al. (2010) reports by determining both time-domain and time-frequency associations in the same community sample of adolescents assessed for the current study but at the age of 29. Participants were also evaluated longitudinally for lifetime EXT disorders assessed in those two investigations including ADHD, ODD, CD, AAB, and substance dependence (alcohol, nicotine, illicit street drugs). EEG activity at age 29 was recorded using a high-density, 61-channel electrode array to allow for regional comparisons of P3-related activity beyond that of site-Pz. As in the Gilmore et al. (2010) study, the current investigation decomposed the ERP data using a novel PCA-based time-frequency method (Bernat et al., 2007) but with a 61-channel EEG recording. Finally, to assess the potential influence of substance exposure on the various brain indices, cumulative measures of substance use were derived using self-report data prospectively ascertained since intake assessment at age 17. Based on existing literature, we hypothesized that subjects with lifetime EXT disorders would continue to display P3-AR in the time-domain across all scalp regions. Furthermore, we hypothesized that time-frequency analyses would reveal decreases in delta- and theta-related components coinciding with P3 activity. Finally, we expected to find that these associations would not be accounted for by cumulative substance use.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 578 male participants who were first assessed at age 17 as part of the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), a community-based longitudinal investigation of the development of substance use disorders and related disorders. Subjects were identified through public records of twin births in Minnesota between January 1, 1972 and December 31, 1978. More complete descriptions of the MTFS are available in Iacono & McGue (2002). Overall, the MTFS sample is generally representative of the population of Minnesota with respect to self-reported mental health and socioeconomic background. The vast majority of participants are Caucasian (99%), consistent with the makeup of the state at the time. All participants and their parents provided written informed assent and consent. After subjects were first assessed at approximately 17 years of age, follow-up assessments were scheduled at ages 20–21, 24–25, and 29–30. Participation rates at the follow-up assessments ranged from 83% (the age-20 assessment) to 92% (current, age-29 assessment). Only subjects who were assessed in-person at the age-29 assessment (N=443) were included in the current study.

Interview and Assessment Procedure

Twin participants were each interviewed by a different interviewer. When visiting together (as at the intake assessment, by design), they were interviewed simultaneously, each in a separate room. DSM III-R (American Psychological Association, 1987) was the diagnostic system in place when the study was initiated. Hence, although questions designed for DSM IV (American Psychological Association, 1994) were included in follow-up assessments, DSM III-R diagnoses are used here to maintain continuity. Childhood disruptive disorders (ADHD, ODD, and Conduct Disorder) were only determined during intake evaluation at approximately age 17. Twins reported on symptoms of ADHD and ODD during clinical interviews using the revised version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA-R; Reich, 2000; Welner, Reich, Herjanic, Jung, & Amado, 1987). They reported on symptoms of CD during interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1987). Diagnoses for AAB were also determined by means of the SCID-II at all assessment phases and assigned to participants who met criteria for ASPD except for the CD requirement (cf. Elkins, Iacono, & Doyle, 1997). Twins were further assessed for substance use disorders using the expanded Substance Abuse Module (Robins, Babor, & Cottler, 1987) developed as a supplement to the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins et al., 1988). At the initial assessment the mother or other caregiver of the twins was interviewed with the DICA-R-Parent version regarding the same diagnoses. All questions asked of the twins were also asked of the mother as they pertained to the twins. To establish diagnoses for each childhood disruptive disorder, a “best-estimate” approach was used combining twin- and mother-reports (Kosten & Rounsaville, 1992; Leckman, Scholomskas, Thompson, Belanger, & Weisman, 1982). Substance use diagnostic criteria were assessed for both licit (alcohol, nicotine) and illicit (amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidine, and sedatives) psychoactive substances. Clinical interviews were reviewed by at least two individuals with advanced clinical training who coded, by consensus, every relevant DSM-III-R symptom and diagnostic criterion. We required that all diagnostic criteria be satisfied for all disorders. Cohen kappa reliability coefficients for the disorders assessed in the current study all exceeded 0.71 (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999).

All diagnoses reflected lifetime psychiatric status as of the age-29 assessment. Lifetime diagnoses were first assigned at study intake when participants were age 17. The occurrence of new disorder was assessed at follow-up assessments scheduled at approximately ages 20, 24, and 29. Diagnostic information was aggregated over these time points such that if an individual ever satisfied criteria for a diagnosis by age 29, he was deemed as having a lifetime occurrence of the disorder.

Diagnostic Procedure

For study purposes, seven groups were formed reflecting whether participants met lifetime diagnoses for one of the following EXT disorders: any childhood disruptive disorder (ADHD, ODD, CD), adult antisocial behavior (AAB), or any substance use dependence disorder (alcohol, nicotine, or illicit drug dependence).

Individuals were assigned to these seven diagnostic groups without regard for possible comorbid diagnoses to produce representative samples of individuals with these conditions; they were thus not mutually exclusive.

To simplify secondary analyses and presentation of some of the results, an additional composite group (‘Any-EXT’) was created reflecting those participants who met diagnosis for any of the seven EXT disorders. Finally, a healthy comparison group was formed consisting of subjects who were free of any EXT disorder, including a diagnosis of abuse for any licit or illicit substance.

Psychophysiological Assessment

ERP data were acquired from all twin participants during their third follow-up assessment at approximately age 29. While subjects sat in a high-backed chair, EEG activity was recorded using the ActiveTwo BioSemi electrode system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) from sixty-one scalp electrodes, digitized at 1024 Hz with a pass-band from DC to 205 Hz. In addition, four monopolar leads recorded electrooculographic (EOG) activity used subsequently to derive horizontal and vertical bipolar EOG channels. Referencing and grounding arrangements for the BioSemi system uses a Common Mode Sense active electrode and a Driven Right Leg passive electrode which form a feedback loop driving the average potential of the subject (the Common Mode voltage) as close as possible to the Analog to Digital Converter (ADC) reference voltage in the AD-box. The ADC reference can be considered as the amplifier “zero”. Greater detail regarding this referencing scheme is available online (http://www.biosemi.com/faq/cms&drl.htm). After data acquisition, all data were re-referenced to the average activity at the two ears.

The rotated-heads oddball paradigm (Begleiter, Porjesz, Bihari, & Kissin, 1984) was used to elicit the P3 response. A script written using E-Prime 1.1 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) controlled stimulus delivery and synchronization with EEG acquisition. During recording, subjects were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible by pressing either a left or right button when target stimuli appeared on a computer monitor. Targets consisted of infrequently occurring schematics of heads with a nose pointed vertically up or down on the screen and only one ear represented on either the left or right side. “Easy” targets (n = 40) consisted of heads with noses pointed towards the top of the screen with the left or right ear appearing directly on the side corresponding to the correct response button. In contrast, “hard” targets (n = 40) consisted of heads rotated 180° so that the nose pointed downward and with either left or right ear appearing on the head corresponding to the opposite response button. Subjects were also instructed to ignore frequently-occurring, non-target stimuli which consisted of ovals (n = 160) interspersed between target trials. All stimuli were displayed for 100 ms, with intertrial intervals randomly varying between 1 and 2 s following a 1.5-s response period.

ERP data processing

EEGs from the rotated-heads task were processed offline in Matlab (version 6.5, Mathworks) mostly via functions contained in the EEGLAB toolbox (Delorme & Makeig, 2004). Continuous data were downsampled to 256 Hz and highpass filtered at 0.1 Hz (6 dB down) using a finite impulse response filter with a Kaiser window of order 1286 and 0.0001 dB maximum passband ripple using the firfilt plugin to EEGLAB. Trial-level, averaged, and overall spectral qualities for each subject-electrode were visually inspected and scalp data were replaced through spherical-spline interpolation (Perrin, Pernier, Bertrand, & Echallier, 1989) if deemed not to be EEG. Blink artifacts were identified with a custom routine based on temporal and spatial cross-correlations. For this, Infomax independent components analysis was performed on each dataset, and components (ICs) were classified as blink-related and subtracted from the data if 1) correlations between bipolar vertical EOG and IC time-series exceeded a threshold of r > 0.70, and 2) correlations between IC electrode inverse-weights (scalp maps) and a spatial template exceeded r > 0.75. Epochs for all target conditions were extracted −1000 to 2000 ms pre-stimulus and the mean of a 200-ms baseline period immediately preceding stimulus onset was subtracted from the raw data. Whole epochs with too much contamination from muscle or other ephemeral causes (cap movement, “pops”, etc.) were detected by means of deviant spectral qualities or kurtosis, respectively (Delorme, Sejnowski, & Makeig, 2007) and removed from the dataset. Prior to averaging, epochs were lowpass filtered at 55 Hz and individual electrode-epochs were excluded if values exceeded a ±75 μV threshold within the region of interest (−200 to 1000 ms).

Time-domain P3 amplitude identification

Grand average waveforms were computed for each of the 61-electrodes and for each subject. Amplitude scores for the P3 peak were derived as the maximum amplitude within a window of 280 to 625 ms post-stimulus onset. If corresponding latencies occurred at either boundary of this window, the data were visually reviewed and the algorithm’s selection was manually overridden if necessary in order to capture the true P3 peak.

Time-frequency principal components analysis (PCA)

ERPs were decomposed into their time-frequency (TF) energy distributions (surfaces) according to techniques outlined in Bernat et al. (2005; see also Bernat et al., 2007). TF techniques can offer certain advantages by characterizing ERP activity in terms of joint frequency and energy components as opposed to observing these signals in time or frequency alone. In particular, in the present investigation we computed TF surfaces from averaged TD waveforms. This facilitates the representation of those TF features most consistently phase-locked to the experimental event (i.e., stimulus onset), and ensures that results will correspond directly with conventional P3 measures taken from condition averages, as is used in the majority of P3AR research. It is worth pointing out that that the current study approach is not intended to provide substantive information about the oscillatory nature of the TF activity assessed – i.e. the degree to which the assessed TF components reflect phase-resetting of ongoing oscillatory activity versus transient amplitude increases phase-locked to the onset of the stimulus, as has been debated in the field (e.g. Yeung, Bogacz, Holroyd, and Cohen, 2004). For example, it is most likely that analysis of trial-level data, rather than averages as assessed here, would be needed to make such inferences. Instead, the intention is to reassess the conventional signals used in P3AR work using TF approaches, providing a useful means of disaggregating overlapping processes indexed in common condition averaged ERP activity.

TF surfaces were computed using the Reduced Interference Distribution (or RID) TF transform from Cohen’s class of transforms (Williams, 2001). The RID offers some advantages relative to other time-frequency transforms such as wavelets (for additional review, see Bernat.et al., 2005). For example, the RID provides transforms with time and frequency shift invariance (where activity will have the same TF representation when shifted up or down in frequency or forwards or backwards in time). Additionally, energy in the time signal is exactly preserved in the TF distribution. A particularly useful attribute of the RID for the current application, is uniform TF resolution. This is in contrast, for example, to non-uniform resolution provided by wavelet TF transforms, which smears low-frequency activity in time and high-frequency activity in frequency. The smearing problem is strongest at the lowest and highest frequencies, and thus low-frequency transient signals such as P3 are vulnerable to this problem. As noted above, previous work from our group has demonstrated that the RID can improve sensitivity to P3AR by characterizing such transient activity associated with P3 (Gilmore et al., 2010). To decompose P3, and the overall ERP, into separable TF components, we employed principal components analysis (PCA) of the TF surfaces (i.e.; TF-PCA), following the methods detailed by Bernat and colleagues (Bernat et al., 2005). In addition to the work with P3 already noted, this TF-PCA approach has been successfully applied to characterize delta and theta activity underlying other widely-studied ERP components such as the error-related negativity (ERN; Bernat et al., 2005; Hall et al., 2007), and feedback-related negativity (Bernat et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2011). In the current study, the TF-PCA was applied to a TF surface containing the relevant time (1 to 1000 ms) and frequency ranges (DC to 12 Hz). As detailed in the initial TF-PCA report (Bernat et al., 2005), this process is equivalent to the application of PCA to time-domain ERP signals (e.g. Chapman and McCrary, 1995; Donchin and Heffley, 1978), with the additional step of rearranging the TF surfaces into vectors to make them appropriate for PCA (analogous to the time-domain signals). That is, the TF surfaces were first rearranged into vectors producing a matrix consisting of unique subject-electrode combinations in each row and TF energy points in columns. Next, PCA was applied to the covariance matrix derived from this data matrix followed by a varimax rotation to maximize simple structure. The component vectors were then rearranged back into surfaces representing each TF-PCA component’s matrix of rotated component loadings for each TF point.

Our TF-PCA resulted in an eight component solution which was chosen by scree plot where visual inspection determined a break in singular values that indicated a point at which the amount of explanatory variance became negligible. Scores for analysis were derived by taking the peak energy (i.e. the TF point with the highest energy) from TF-PC weighted surfaces. This method was similarly used by Gilmore et al. (2010) to successfully discriminate various EXT groups from controls and allows for evaluations between the TF (peak energy) and time (peak P3 amplitude) domains. TF decompositions were also derived from site-Pz to facilitate comparison to the Gilmore et al. (2010) report.

Assessment of Recent Substance Use

Participants were instructed not to use alcohol, illicit drugs, or stimulant medications within 24 hours of their assessment. Recent substance use (i.e., 24-hours prior to EEG assessment) was ascertained through breathalyzer analysis and a self-report. No participants in the current study had elevated blood alcohol content (BAC) levels based on breathalyzer analysis. Self-report data were gathered using an abbreviated checklist from the SAM to determine whether participants used any substance that might influence the EEG (i.e., coffee, soda, tobacco/cigarettes, prescription drugs, or any other drugs) within the past 24-hours. A total of 73 participants indicated recent use. To evaluate whether these participants were over-represented in the EXT groups, which could potentially influence EEG results, a dichotomous variable was formed reflecting those who reported using any or none of these substances prior to EEG assessment. This group was then cross-tabulated with the Any-EXT group and controls. The result was non-significant, χ2(1, N = 73) = 0.13, p = 0.71, confirming that those diagnosed with any EXT disorder did not differ overall from controls in the effects of their past 24-hour substance ingestion.

Task performance

Three task performance measures were evaluated: False alarms constituted the number of non-target stimuli (160 ovals) incorrectly identified as targets. Reaction time was defined as the average time subjects took to make a button press to identify target stimuli. Total hits reflected the number of both easy and hard targets correctly identified from the 80 presented.

The effect of the most comprehensive diagnostic grouping variable (i.e., Any-EXT) on the three task performance measures was assessed in an ANOVA with group as the sole fixed effect. These task performance measures were skewed. Thus, prior to analyses, false alarm as well as reaction time data were log transformed whereas the proportion of hits data underwent arcsine transformation. Data were missing for 1 participant.

Participants Available for EEG Analyses

Of the 578 twin participants who were assessed at intake, 443 (77%) returned for in-person assessment at the third follow-up, with the remainder participating by phone because they were unable to travel to our laboratory. Among these 443 visiting participants, 9 did not have dense array EEG data (e.g., completed low density EEG instead), 53 subjects had to be dropped from analyses at the time of this investigation due to technical/equipment problems (e.g., common mode ground electrode out of range, recording of event timing information was corrupted), and 15 subjects were dropped due to excessive artifacts whereby more than 10% of channels were deemed unusable. Three participants were excluded because they had incomplete diagnostic data. Furthermore, due to the nature of our sample criteria, 60 subjects were not assigned to either the diagnostic or control groups. These subjects either met criteria for substance abuse but not dependence (n = 26), or were only one symptom short of meeting DSM criteria for dependence (n = 34), and hence failed to meet our criteria for any of the EXT groups. Given their elevated symptom status, they were excluded from the Control group as well. Thus, 303 (69%) of the 443 available participants with both lifetime diagnostic and EEG data were included for final analysis.

To determine if those with usable data (n = 303) differed from those who were not in the final dataset for any reason (n = 275), comparisons were made on two intake variables: P3 amplitude and EXT diagnosis. P3 amplitude data was obtained for 501 participants at study intake at site-Pz using the same ERP eliciting task described previously (cf. Iacono et al., 2002). Among those with intake P3 data, 264 participants who were included in the current study were compared to the 237 who were not included. Furthermore, to evaluate the possibility that those who were included and excluded in the current study differed in their likelihood of ever having been diagnosed with an EXT disorder at intake, the proportions of subjects who were ever diagnosed in the two groups were compared.

The effect of the grouping variable (participating vs. non-participating subjects) on intake P3, was assessed using an ANOVA with group as the sole fixed effect. A chi-square analysis was performed to determine whether the proportions of EXT diagnoses varied between the two groups.

Statistical Analyses of Time-Domain and Time-Frequency Data

To reduce the number of statistical comparisons, a spatial PCA was performed to derive topographic areas defined by similarity in P3-amplitude for time-domain data. PCA was conducted on P3 peak amplitude scores from each of the 61 electrode sites, followed by Varimax rotation. Each electrode was assigned to a spatial component based on its highest loading. The mean activity of all electrodes within each region constituted our measure of P3 amplitude for that region. These P3 amplitude-defined regions were used in turn to determine corresponding P3 latency and TF components.

A series of 3 (regions as identified by the regional PCA described above) by 2 (group) ANOVAs were conducted using linear mixed models (LMM) as implemented in PROC MIXED in SAS. Regions (the three spatial modes) served as a within-subjects effect and each of the 7 EXT groups as well as the Any-EXT composite group serving as the between-subjects effect in separate analyses. A random effect of region was modeled at the individual subject level, resulting in a 3 × 3 covariance matrix of freely estimated random effects, corresponding to a MANOVA model. In order to correct for correlated observations due to having twins in the sample, the model included a random effect of region at the twin pair level as well. In addition to allowing us to accommodate non-independence represented by twins, the LMM approach uses all available data, unlike standard repeated measures ANOVA, an approach that is appropriate when data are missing at random (Little & Rubin, 2002).

For comparative purposes, P3 amplitude measured from site-Pz was also evaluated for each EXT group through a series of univariate ANOVAs, treated as LMMs, with a random intercept term to account for the correlation between members of a twin pair. This analytical approach was also used for other univariate comparisons including participation analyses, task performance, etc. A significance criterion of alpha < .05 was set for all tests. In order to obtain effect sizes, we converted the mean difference between controls and comparison group for each of the three regions examined in the MANOVAs into statistics analogous to Cohen’s d, using a standard formula for converting t-statistics to d (Rosenthal, 1991).

Results

Task Performance

Consistent with expectations from past reports (cf. Iacono et al., 2002), results revealed that none of the three task performance measures (false alarms, reaction time, total hits) differed significantly between controls and those with any EXT disorder (all Fs < 0.96, all p-values > 0.33).

Participation Effects

ANOVA results revealed that intake P3 amplitude did not significantly differ between participants who were included versus excluded in this study: F(1, 456) = 1.75, p = 0.19. Furthermore, the percentages of participants with any of the seven lifetime EXT diagnoses in each of the two groups were 71.1% and 61.1%, respectively, a non-significant difference, χ2 (1, N = 487) = 0.1, p = 0.73. Overall, these analyses indicate that included participants did not differ from nonparticipants on key measures, and thus the age-29 participating group does not appear to represent a biased subset of the age-17 intake sample.

Regional PCA of EEG data

Based on the scree plot derived using peak P3 amplitude values for all 61 electrodes, three factors were retained accounting for 60.67% of the variance. These factors thus comprised the three topographic regions for analyses: frontal (27 electrodes), central-parietal (14 electrodes including site-Pz), and parietal-occipital (20 electrodes). Figure 1 displays these three regions. The mean values taken from these electrodes constituting each region were derived separately for P3 amplitude (microvolts, μV), P3 latency (ms), and weighted peak energy units for each of the TF components.

Figure 1. Topographic regions derived from principal components analysis (PCA).

Three topographic regions were identified by PCA using P3 peak amplitude scores from each of the 61 electrode sites, followed by Varimax rotation. Each electrode was then assigned to a spatial component based on its highest loading. For group comparisons, mean activity of all electrodes within each region constituted our measure of P3 amplitude for that region. These P3 amplitude-defined regions were then used to determine corresponding P3 latency and TF component values.

Association between Externalizing and Time-Domain P3 Amplitude

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) for site-Pz and regional P3 amplitude peak/latency values. The omnibus F-values and p-values associated with statistical comparisons for the various EXT groups, including the Any-EXT group, are also presented in this table. For summary purposes effect size graphs coinciding with the Any-EXT group are presented in Figure 2. Lastly, the grand average P3 waveforms for the Any-EXT group are displayed in Figure 3(A–D).

Table 1.

Means (SD) for site-Pz and regional time domain P3 peak amplitude (μV), P3 latency (ms), and results of statistical comparisons

| Participant Group | P3 Amplitude & Latency at site-Pz | P3 Amplitude & Latency by Region | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | ANOVA results | ||||||||

| Descriptives | T-test Results | Frontal | Central-Parietal | Posterior-Occipital | Group (G) | Region (R) | G x R | ||

| Mean (SD) | p-values | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-values | ||||

| Controls (N = 84) | Amplitude | 15.77 (4.20) | ______ | 8.65 (3.17) | 13.55 (4.10) | 10.49 (3.51) | ___________ | ___________ | ___________ |

| Latency | 396.33 (40.36) | ______ | 393.31 (50.32) | 395.96 (42.50) | 406.42 (35.18) | ___________ | ___________ | ___________ | |

| ADHD (N = 22) | Amplitude | 12.29 (3.60) | .001 | 8.00 (2.70) | 10.72 (3.52) | 8.55 (2.59) | .043 | <.001 | .005 |

| Latency | 417.11 (52.14) | .118 | 377.02 (39.34) | 395.94 (50.09) | 422.38 (54.04) | .889 | <.001 | .017 | |

| ODD (N = 38) | Amplitude | 12.53 (3.60) | <.001 | 7.78 (2.65) | 10.95 (3.18) | 8.32 (2.93) | .001 | <.001 | .010 |

| Latency | 401.45 (38.09) | .517 | 378.34 (35.92) | 388.66 (37.36) | 414.68 (33.86) | .652 | <.001 | .022 | |

| CD (N = 76) | Amplitude | 13.21 (4.87) | <.001 | 8.09 (3.04) | 11.60 (4.50) | 8.67 (3.73) | .007 | <.001 | .003 |

| Latency | 399.65 (40.60) | .647 | 384.72 (37.01) | 396.05 (42.84) | 411.42 (38.26) | .887 | <.001 | .145 | |

| AAB (N = 53) | Amplitude | 12.90 (3.98) | <.001 | 8.46 (2.61) | 11.64 (3.51) | 8.49 (3.19) | .003 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Latency | 396.04 (39.25) | .968 | 377.08 (35.23) | 390.60 (42.34) | 408.73 (33.96) | .348 | <.001 | .067 | |

| Alcohol (N = 136) | Amplitude | 13.64 (4.00) | <.001 | 7.92 (2.78) | 11.78 (3.49) | 8.81 (3.15) | <.001 | <.001 | .038 |

| Latency | 399.04 (43.13) | .671 | 378.34 (39.42) | 391.80 (39.20) | 409.57 (38.80) | .517 | <.001 | .022 | |

| Nicotine (N = 139) | Amplitude | 13.19 (4.37) | <.001 | 8.18 (2.85) | 11.63 (3.84) | 8.56 (3.38) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Latency | 398.89 (43.97) | .692 | 376.30 (37.71) | 388.34 (37.79) | 410.13 (37.17) | .183 | <.001 | .006 | |

| Illicit (N = 58) | Amplitude | 13.93 (4.89) | .020 | 8.23 (3.07) | 11.98 (3.92) | 9.11 (3.25) | .012 | <.001 | .166 |

| Latency | 396.65 (42.34) | .967 | 376.61 (41.97) | 388.18 (34.64) | 407.94 (34.98) | .449 | <.001 | .079 | |

| Any-EXT (N = 219) | Amplitude | 13.60 (4.53) | <.001 | 8.07 (3.00) | 11.79 (3.99) | 8.23 (3.41) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Latency | 399.52 (43.25) | .600 | 378.69 (39.67) | 391.71 (37.96) | 409.69 (36.42) | .389 | <.001 | .012 | |

Note: “Any-EXT” refers to participants who met lifetime diagnosis for any of the seven EXT disorders in the study by age 29.

Figure 2. Degree to which time-domain P3 amplitude is reduced for those with any externalizing disorder.

Effect sizes corresponding to each of the three topographic regions from the comparisons between the composite Any-EXT group versus healthy controls are displayed. Effect sizes were obtained by converting the mean microvolt (μV) difference between controls and the Any-EXT group for each of the three regions examined in the MANOVAs into statistics analogous to Cohen’s d, using a standard formula for converting t-statistics to d (Rosenthal, 1991). Any-EXT refers to any participant meeting lifetime diagnosis for an externalizing disorder by age-29.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 (A–D). Grand average waveforms for time-domain P3 coinciding with activity at the three topographic regions and site-Pz for the composite Any-EXT group and healthy controls.

Presented schematically are the frontal (Figure 3A), central-parietal (Figure 3B), and parietal-occipital (Figure 3C) topographic regions identified by PCA as well as activity at site-Pz (Figure 3D). The grand average waveform activity associated with the target trials for the Any-EXT (i.e., any participant meeting lifetime diagnosis for an EXT disorder by age-29) and control groups are also displayed corresponding to these topographic sites.

Amplitude

Table 1 shows that the main effect of region was significant for amplitude for all group comparisons, all Fs > 99.67, all p-values < .001, with the largest amplitudes associated with the central-parietal region (see also Figure 3). Table 1 further reveals that significant group differences in P3 amplitude were seen for both site-Pz (all Fs > 5.27, all p-values < 0.02) as well as the topographic (all Fs > 4.21, all p-values < 0.04) analyses. Figure 2 illustrates that the nature of these topographic effects varied by region with the frontal region producing a smaller effect (ES = 0.23) than either of the two posterior regions: central-parietal (ES = 0.44,), parietal-occipital (ES = 0.48). An effect size of 0.46 was observed at site-Pz.

Latency

P3 latency did not significantly differ between the EXT groups from controls for both the topographical (all Fs < 1.78, all p-values > 0.18), and site-Pz analyses (all Fs < 3.58, all p-values > 0.06). Significant main effects for region were detected (all Fs > 16.60, all p-values < .001) across all comparisons, indicating that latencies progressively increased from the frontal to posterior regions.

Time-Frequency PCA Decomposition

Eight principal components accounting for 85.74% of the variance were retained based on the scree plot when decompositions were made using all 61 electrodes. Similar TF components accounting for 88.21% of the variance were also retained from site Pz decompositions. Figure 4 displays both the 61-channel and site-Pz decompositions that were paired based on patterns of TF-PC peak correlations and cross-factor loadings. The patterns of peak correlations associated with the pairings were all significant (at p < .001) and greater than 0.87 (median correlation = 0.96). The absolute values of the associated congruence coefficients (CCs; presented in Figure 4) were similarly large for those pairs (all CCs greater than 0.57; median CC = 0.85). The numbers associated with each TF component (e.g., PC1) reflect the ascending order of the component based on the amount of variance accounted for in the varimax-rotated solution.

Figure 4. Grand average waveforms and time-frequency component alignment from the 61-channel and site-Pz decompositions.

Grand-averaged time-domain and time-frequency (Avg) plots corresponding to the 61-channel (left panel) and site-Pz (right panel) are presented at the top. The eight time-frequency components (PCs 1–8) retained from the principal components analysis decomposition are presented below the grand averages. For all time-frequency plots, x-axis is time from stimulus onset (0 ms) to 1000 ms, and y-axes range from 0 – 5.75 Hz. Time-frequency components on the left panel corresponding to the 61-channel decompositions are numbered (PCs 1–8: highest to lowest) based on the amount of variance for which they account in the varimax-rotated solution. Analogous TF-PCs derived from site-Pz (right panel) were aligned to the components from the 61-channel solution based on patterns of TF-PC peak correlations and cross-factor loadings. Congruence coefficients (CC) associated with the TF-PC pairings are also indicated.

For the 61-electrode solution (and its corresponding site-Pz component), principal component 1 (PC1, or PC6 at site-Pz) reflected late slow-wave offset activity at the delta frequency (“Late slow-wave delta”). PC2 (PC8 at site-Pz) reflected theta activity coinciding with the P2-ERP (“P2 theta”). PC3 (PC4 at site-Pz) constituted high-delta activity that coincided with the rise and peak of P3-ERP (“P3 high-delta”). PC4 (PC5 at site-Pz) spanned the N1-P2-N2 complex in terms of time course at the delta frequency (“N1-P2-N2 delta”). PC5 (PC3 at site-Pz) reflected theta activity that captured the N2-P3 ERP complex (“N2-P3 theta”). PC6 (PC2 at site-Pz) appeared as high-delta activity spanning the P2-N2 ERP complex (“P2-N2 high-delta”). PC7 (also PC7 at site-Pz) constituted delta activity that primarily spanned the P2-N2-P3 complex (“P2-N2-P3 delta”). Finally, PC8 (PC1 at site-Pz) also reflected delta activity that spanned the later aspects of the P3-ERP (“late-P3 delta”).

Association between Externalizing and Time-Frequency Components

With time-domain results revealing broad and significant reductions for P3 amplitude across all EXT groups, time-frequency comparisons were made using the composite Any-EXT group for ease of presentation. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) for the mean weighted energy unit values associated with each topographic region, their corresponding site-Pz TF component values, as well as p-values associated with comparisons between Any-EXT and controls. Effect sizes for the regional comparisons are provided in Figure 5. A significant effect for region was detected across all comparisons for all TF-PCs (all Fs > 112, all p-values < .001). Similar to the time-domain results, the largest signals were generally observed for the central parietal region.

Table 2.

Mean (SD) for weighted energy units for site-Pz and regional time-frequency components, and results of statistical comparisons between Controls (n = 84) and the Any-EXT group (n = 219)

| Principal Components (PC) Derived from 61-Channel Montage | Time-frequency Principal Components by Region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analogous component at site-Pz | Topographic Regions | ANOVA results | |||||||

| Descriptives | T-test Results | Frontal | Central-Parietal | Posterior-Occipital | Group (G) | Region (R) | G x R | ||

| Mean (SD) | p-values | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-values | ||||

| Late slow-wave delta (PC1) | Controls | 15.99 (10.54) | .005 | 3.40 (2.27) | 8.68 (5.56) | 5.78 (4.50) | .043 | <.001 | .022 |

| Any-EXT | 12.22 (9.47) | 3.33 (2.25) | 7.52 (5.26) | 4.58 (3.27) | |||||

| P2-theta (PC2) | Controls | 18.42 (10.28) | <.001 | 3.43 (2.36) | 7.04 (4.42) | 5.68 (2.98) | <.001 | <.001 | .005 |

| Any-EXT | 14.65 (9.35) | 2.86 (2.12) | 5.45 (3.77) | 4.41 (2.94) | |||||

| P3 high-delta (PC3) | Controls | 8.17 (4.75) | <.001 | 5.85 (3.72) | 12.63 (7.77) | 9.79 (5.86) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Any-EXT | 6.21 (4.44) | 4.40 (3.44) | 9.08 (6.67) | 7.45 (4.77) | |||||

| N1-P2-N2 delta (PC4) | Controls | 8.33 (5.62) | .002 | 4.19 (2.84) | 7.03 (4.07) | 5.81 (3.46) | <.001 | <.001 | .022 |

| Any-EXT | 6.92 (5.23) | 3.76 (2.63) | 5.70 (3.76) | 4.86 (2.95) | |||||

| N2-P3 theta (PC5) | Controls | 15.86 (9.14) | .024 | 2.31 (1.56) | 5.45 (3.82) | 5.89 (3.30) | .027 | <.001 | .202 |

| Any-EXT | 11.59 (7.96) | 2.05 (1.55) | 4.73 (3.74) | 5.02 (3.01) | |||||

| P2-N2 high-delta (PC6) | Controls | 8.44 (4.73) | <.001 | 5.63 (4.15) | 11.45 (8.06) | 11.58 (7.32) | .001 | <.001 | .023 |

| Any-EXT | 6.18 (4.36) | 5.05 (3.75) | 9.45 (7.36) | 9.06 (5.92) | |||||

| P2-N2-P3 delta (PC7) | Controls | 22.82 (12.97) | <.001 | 7.07 (4.42) | 15.98 (8.90) | 10.54 (6.72) | <.001 | <.001 | .002 |

| Any-EXT | 16.62 (11.46) | 6.18 (4.27) | 12.44 (8.69) | 7.67 (5.64) | |||||

| Late-P3 delta (PC8) | Controls | 12.60 (8.47) | <.001 | 6.18 (3.46) | 13.97 (7.75) | 10.22 (6.26) | .001 | <.001 | .013 |

| Any-EXT | 9.88 (6.86) | 5.44 (3.58) | 11.38 (7.24) | 8.06 (5.32) | |||||

Note: “Any-EXT” refers to participants who met lifetime diagnosis for any of the seven EXT disorders in the study by age 29.

Figure 5. Degree to which time-frequency components are reduced for those with any externalizing disorder.

Effect sizes corresponding to each of the three topographic regions from the comparisons between the composite Any-EXT group versus controls for each of the eight TF-PCs depicted in Fig. 4 and described in Table 2. Effect sizes were obtained by converting the mean weighted energy unit differences between controls and the Any-EXT group for each of the three regions examined in the MANOVAs into statistics analogous to Cohen’s d, using a standard formula for converting t-statistics to d (Rosenthal, 1991). Any-EXT refers to any participant meeting lifetime diagnosis for an externalizing disorder by age-29.

Also similar to the time-domain findings, group comparisons were consistent, with significant reductions observed for all eight TF-PCs in the Any-EXT group across all three regions (all Fs > 4.11, all p-values < 0.04) as well as for their analogous components at site-Pz (all Fs > 4.23, all p-values < 0.04). The regional effect sizes across the TF-PCs followed the same pattern seen in the time-domain, with increasing effects observed from the frontal to posterior regions: median regional ES: Frontal = 0.22 (range = 0.02 – 0.49); Central-Parietal = 0.34 (range = 0.17 – 0.55); Parietal-Occipital = 0.42 (range = 0.31 – 0.53). This was particularly the case for the late slow-wave delta component where the effect at the parietal-occipital region (ES = 0.31) was more than six times the effect observed frontally (ES = 0.02). The one notable exception to this general trend was seen in the P3 high-delta component. Compared to the other TF-PCs, this component displayed overall larger effects across all topographic regions (median regional ES = 0.53), which included large frontal effects (ES = 0.49) not observed in the time-domain (Frontal ES for Any-EXT = 0.23). For site-Pz, the median effect size across the eight components were comparable to the effect sizes seen topographically in the two posterior regions (Median ES = 0.39, range = 0.26 – 0.51).

How Effects Differ by Topographic Region

The various group comparisons revealed significant Group x Region interactions for P3 amplitude, latency, and time-frequency components (see Tables 1 and 2). These interactions were explored by inspecting group means, effect size graphs, and profile plots, as well as by conducting univariate ANOVAs that compared the groups on the components at each of the three regions. Overall, these interaction analyses coincided with the observations of topographic effect sizes. For instance, time-domain interactions resulted in non-significant frontal discriminations across all seven groups (all Fs < 2.70, all p-values > 0.10), but significant effects at the two posterior regions (all Fs > 4.86, all p-values < 0.03). Figure 6 presents the time-domain profile plots coinciding with the Any-EXT group. These results were generally observed for the Any-EXT analyses in the time-frequency domain. Although significant interactions were not detected for the N2-P3 theta component, the majority of TF-PCs (P2-theta, N1-P2-N2 delta, P2-N2-P3 delta, Late-P3 delta), resulted in univariate regional analyses that produced non-significant frontal discriminations (all Fs < 3.48, all p-values > 0.06), but significant effects at the two posterior regions (all Fs > 4.39, all p-values < 0.04).

Figure 6. Profile plot for time-domain P3 peak amplitude.

Time-domain profile plots coinciding with the Any-EXT and control groups are displayed to illustrate the nature of the significant Group x Region interactions for P3 amplitude comparisons. This pattern was generally observed for the Any-EXT analyses in the time-frequency domain, i.e., non-significant frontal discriminations but significant effects at the two posterior regions (i.e., central-parietal, parietal-occipital).

The Any-EXT group was further used to explore the P3 latency interactions. ANOVAs revealed that P3 latencies did not significantly differ at the two posterior regions (Fs < 0.50, p-values > .48), but differed significantly at the frontal region (F(1, 206) = 5.13, p = 0.02) with those in the Any-EXT group (mean = 378.69) averaging latencies that were 14.62 ms faster versus Controls (mean = 393.31).

EXT Comorbidity and P3 Amplitude

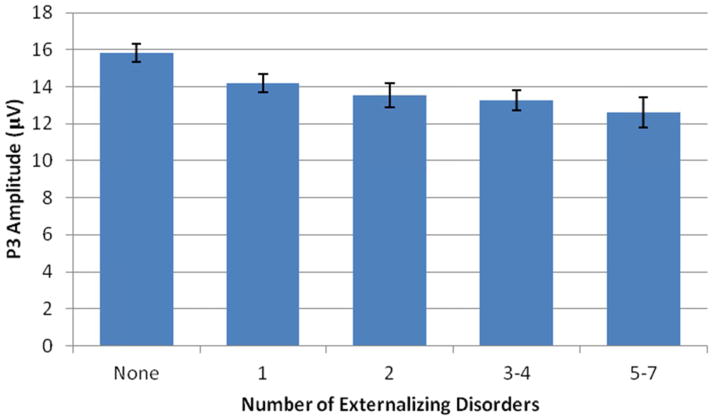

Our conceptual model predicts increases in ERP amplitude with increasing levels of the underlying disinhibitory trait. To address this, we examined associations between the number of comorbid disorders an individual had and ERP amplitude. To avoid very heterogeneous group sizes we created the following groups: no diagnoses (29%), one diagnosis (26%), two diagnoses (14%), three or four diagnoses (22%), and five to all seven diagnoses (9%). For ease of presentation, we present findings for P3 at site-Pz only, although similar results for the grouping variable were observed for the regional P3 and TF analyses (with the exception of PC1). The Spearman correlation between the grouping variable and P3 amplitude at site-Pz was −.243, p < .001. An ANOVA of P3 amplitude, with a random intercept to account for the nonindependence of twins, yielded a significant effect of number of comorbid disorders, F(4, 250) = 4.46, p = .002. The comparison group without any disorders differed significantly from each or the others, t-statistics ranging from 2.42 to 3.52, p- values ranging from .016 to .001. Figure 7 depicts these results graphically and illustrates the approximately linear decrease in P3 amplitude across groups.

Figure 7. Reduction in P3 amplitude in relation to the number of externalizing disorders.

Mean amplitude of the P3 at site-Pz, with error bars representing 1 SE, is given for groups defined on the basis of the number of EXT diagnoses. The pattern indicates that greater comorbidity of lifetime EXT disorders is associated with greater reduction in P3 amplitude. Because the number of subjects with a given number of diagnoses declines with the number of diagnoses, we created groups of relatively comparable size by collapsing some categories.

Effects of Cumulative Substance Use

Although group differences on the brain measures did not appear to be accounted for by recent 24-hour substance ingestion, it remains uncertain whether these differences potentially reflect the neurotoxic effects of prolonged cumulative use. To evaluate this possibility, participant substance use history was ascertained from intake through third follow-up using the SAM. Three cumulative use measures were derived: 1) total number of cigarettes smoked per day during heaviest use, and 2) lifetime number of intoxications (which were both reported from intake through second follow-up), and 3) the number of times using any illicit drugs from intake through third follow-up. For each measure, dichotomous groups were created using 10–90 decile splits from participant responses. These groups were then compared on regional time-domain and TF-PC measures using ANOVAs.

Results revealed no significant group differences on time-domain (all F’s < 1.82, all p-values > 0.18) or time-frequency components (all F’s < 3.67, all p-values > 0.06 across all comparisons), suggesting that group differences on these brain measures were not necessarily due to the cumulative exposure to alcohol, cigarettes, or illicit substances.

Discussion

This investigation presented a comprehensive multi-regional assessment of P3-related brain activity in a male community sample at uniform age to demonstrate the utility of these measures as broad indices of EXT. Furthermore, this study extended both the time-domain (Iacono et al., 2002) and time-frequency (Gilmore et al., 2010) reports of these participants as adolescents by assessing them in adulthood 12 years later. Time-domain P3 analyses clearly showed significant posterior amplitude reductions in subjects with a lifetime history of EXT. Results were also clear for the time-frequency analyses, with all eight TF-PCs showing reductions in the Any-EXT group. In addition, P3 amplitude was inversely correlated with the number of EXT disorders a person possessed. Those with even a single EXT disorder showed P3AR, and P3AR tended to become more pronounced the greater the level of comorbidity. These results indicate that P3 amplitude is sensitive to the degree to which EXT pathology is present. Finally, assessment of substance use history indicated that these effects were not necessarily due to prolonged substance exposure per se, consistent with findings of previous studies (Costa et al., 2000; O’Connor, Hesselbrock, & Tasman, 1986; Iacono et al., 2002; Malone et al., 2001; Pfefferbaum, Ford, White, & Mathalon, 1991) and frontal P3-AR does not appear to be related to substance exposure per se but rather to familial risk for alcoholism.

Despite the observed association of P3AR with EXT, consistent with past reports, the task performance of those with EXT was not abnormal, and as we have shown elsewhere, not due to their failure to attend to the probabilistic nature of the target stimuli (Gilmore et al. 2012). These results thus point to the possibility that P3AR reflects dysfunction in the brain mechanisms responsible for P3 generation and is not secondary to task inattention or poor cooperation. Taken together, these findings lend further support to the notion that these neurophysiological measures are tapping into a neural substrate underlying behavioral disinhibition.

Time-Domain P3 Amplitude and Externalizing

This study demonstrated that P3-AR continues to remain an effective index of lifetime EXT that was apparent especially over the posterior regions (i.e., central-parietal, parietal-occipital). These effects were also comparable at site-Pz, confirming that activity at this site provides enduring utility as a summary index for P3-EXT investigations. Our results extend the findings from Iacono et al. (2002) by showing that P3-AR, first observed at age 17, was present as well at age 29. Thus our results do not support the view that P3-AR is a developmentally-limited indicator or predictor of EXT that shows diminishing utility past late childhood (e.g., Hill et al., 1999, Hill et al., 2009). Instead, time-domain P3-AR appears to index adults with a range of lifetime EXT disorders, including diagnoses made during childhood (i.e., ADHD, ODD, CD).

Our findings are also somewhat discrepant to investigations that show evidence for significant frontal P3-AR in those with substance dependence such as alcohol (Costa et al., 2000; Kamarajan et al., 2005), or cocaine with comorbid disinhibitory behavioral disorders (Bauer, 1997). Although difficult to reconcile based on available information, one possibility is that the visual rotated-heads paradigm used in the current study does not elicit strong frontal responses. Indeed, in this study effect sizes observed at the two posterior regions (central-parietal = 0.44, parietal-occipital = 0.48) effectively doubled the frontal estimate (0.23) across the EXT groups (see Figure 2). Furthermore, to our knowledge, no study finding significant frontal effects in adults with EXT has done so using the rotated-heads paradigm. Another possibility is source of sample recruitment. Many investigations finding frontal effects in subjects with alcohol dependence, for instance, have done so using treatment samples (e.g., Kamarajan et al., 2005), or samples selected to have high familial risk for alcoholism (Costa et al., 2000; Hada et al., 2001; Prabhu et al., 2001). Although important, these samples may include particularly severe cases putatively associated with pre-existing frontal abnormalities (Giancola, Moss, Martin, Kirisci, & Tarter, 1996; Giancola & Tarter, 1999).

Time-Frequency Components and Externalizing

Time-frequency decomposition of the ERP waveform produced a number of effective measures of EXT in both the delta and theta frequency ranges. Such observations support and extend the findings of Gilmore et al. (2010) which assessed the sample from the current study over a decade earlier at age 17 on TF components derived from site-Pz. For instance, we demonstrated that a delta component coinciding with the P2-N2-P3 complex (both regionally and at site-Pz) showed widespread posterior reductions in the Any-EXT group, displaying effect sizes (e.g., at site-Pz = 0.47) that were some of the larger effects observed across all TF-PCs, and comparable to the time-domain peak effects (site-Pz ES = 0.46). In further support of their study, another delta component coinciding with the peak of P3 (P3 high-delta) effectively indexed the Any-EXT group as well. In fact, this component produced the largest effect overall at site-Pz (ES = 0.51). Further noteworthy were the results of the regional analyses which revealed a robust effect across all three topographic sites, with prominent frontal effects (Any-EXT = 0.49, see Figure 5) not apparent in the time-domain analyses (Any-EXT = 0.23, see Figure 2).

In addition, TF-PCs in the theta range provided effective indices of EXT (P2-theta, N2-P3 theta), with both regional and site-Pz comparisons revealing significant reductions on these components and displaying comparable effect sizes to those seen for the delta-related TF-PCs. It should be noted that theta activity has been shown to be influenced by frontal sources (Basar-Eroglu et al., 1992), and frontal cortex is especially susceptible to the effects of substance exposure (e.g., Goldstein & Volkow, 2002; Moselhy et al., 2001; Oscar-Berman, 2000). However, our analyses showed that none of the cumulative substance use measures were significantly related to these theta components (or any of the P3-related measures in this study), suggesting that these components additionally provide utility as biomarkers of EXT. This finding is consistent with those of Jones and colleagues (2006) who found reductions in TF energy in both theta and delta ROIs in alcohol-dependent adults.

Collectively, the TF-PCs at the delta and theta frequencies components canvassed a wide area on the ERP waveform including the N1 through the late P3 indicating that the decomposition techniques offered a comprehensive and detailed assessment of the potential neurophysiological abnormalities associated with EXT. Furthermore, based on the approach we followed to define TF and TD measures, certain TF components offered more effective measures of frontal EXT-related variance than time-domain P3 amplitude.

P3-Related Brain Measures as Candidate Endophenotypes

This study further supports the notion that time-domain P3-AR reflects a candidate endophenotype for disorders characterized by behavioral disinhibition (see reviews by Iacono et al., 2008, and Iacono & Malone, 2011). Other evidence includes the finding that visual P3 amplitude is heritable (see meta-analysis by van Beijsterveldt & van Baal, 2002); a finding which has also been demonstrated for this sample at age 17 (Yoon, Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2006). Molecular genetic investigations have documented significant linkage to various chromosomes with visual P3 (Begleiter et al., 1998; Porjesz et al., 2002), as well as a dopamine receptor A1 allele which was linked to P3-AR in children at high familial risk for alcoholism (Hill et al., 1998). Also, results of a bivariate genome scan indicated that a chromosome region near the ADH3 locus may influence both P3 amplitude and risk for alcoholism (Williams et al., 1999) which is noteworthy since this region was also linked to the maximum number of drinks consumed in a day (Saccone et al., 2000).

Genetic investigations of time-frequency components are also yielding promising results. For example, an association was found between theta power and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the glutamate receptor GRM8 (Chen et al., 2009). In addition, an association between frontal theta TF component and a SNP in the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, CHRM2, has been reported (Jones, Pojesz, Almasy, & al., 2004), which is also linked to performance IQ (Dick et al., 2007), cognition, and memory (Comings, Wu, Rostamkhani, McGue, & Iacono, 2003). Significant associations with SNPs in CHRM2 were also found with comorbid alcohol dependence and major depression (Wang, Hinrichs, Stock, Budde, et al., 2004).

Limitations

Although both time-domain and time-frequency analyses uncovered various regional differences in activity between EXT subjects and controls, this does not allow for inferences regarding the putative intracranial current sources that may be involved since scalp electrical potential data does not reveal unique sets of sources for any given potential field (Michel et al., 2004). More sophisticated analyses using functional brain imaging techniques such as low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (LORETA) would offer the ability to identify these sources (cf. Chen et al., 2007). Also, although assessment of both recent and prolonged substance exposure did not reveal any associations with the group results, this may be due to the limited time window for age in the current study. Also, although we have no evidence that participants were using drugs at the time of testing and we excluded those who admitted doing so or who had positive breathalyzer tests, we did not conduct toxicology screens to confirm that participants were free from the effects of illicit drugs. Future follow-up assessments will be necessary to evaluate such effects. Furthermore, given that this is the first report using the TF-PCA method on higher-density EEG data from our lab, prospective investigations evaluating the stability and replicability of these effects are needed. Finally, although this community-based sample offers unique research opportunities, it is nevertheless comprised of predominantly Caucasian twin participants from Minnesota, potentially limiting generalizability to samples similarly composed.

Conclusion

This study presented a multimethod and multi-regional assessment of stimulus-evoked brain activity in adult participants presenting various lifetime EXT disorders. We demonstrated that EXT was associated with broad topographic reductions in both time- and time-frequency domains related mainly to posterior P3 activity. This study extends and elaborates the age-17 findings by Iacono et al. (2002) and Gilmore et al. (2010) by demonstrating that P3-related measures provide effective brain indices of lifetime EXT from adolescence through adulthood. Collectively, these community-based studies suggest that such measures may provide effective multivariate endophenotypes (Gilmore et al., 2010; Iacono et al., 2000) across development that index the neural processes associated with behavioral disinhibition (Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants R01 DA5147 (Iacono), K01 AA015621 (Malone), and K08 MH 080239 (Bernat), and by the Dean’s Summer Scholarship Award from the Center for Teaching and Learning at Augsburg College (Yoon).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, D.C: Author; 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin AP, Vedeniapin AB, Sirevaag EJ, Bauer LO, O’Connor SJ, Kuperman S, Rohrbaugh JW. The P300 brain potential is reduced in smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2000;149:409–413. doi: 10.1007/s002130000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RJ, Johnstone SJ, Clarke AR. A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. Event-related potentials. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114:184–198. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar-Eroglu C, Basar E, Demiralp T, Schurmann M. P300-response: possible psychophysiological correlates in delta and theta frequency channels. A review. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1992;13:161–179. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(92)90055-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO. Antisocial personality disorder and cocaine dependence: their effects on behavioral and electroencephalographic measures of time estimation. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2001a;63:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO. CNS recovery from cocaine, cocaine and alcohol, or opioid dependence: a P300 study. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001b;112:1508–1515. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. P300 decrements in teenagers with conduct problems: implications for substance abuse risk and brain development. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. CSD/BEM localization of P300 sources in adolescents “at-risk”: evidence of frontal cortex dysfunction in conduct disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:600–608. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. Brain maturation and subtypes of conduct disorder: interactive effects on P300 amplitude and topography in male adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:106–115. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, O’Connor S, Hesselbrock VM. Frontal P300 decrements in antisocial personality disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:1300–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baving L, Rellum T, Laucht M, Schmidt MH. Children with oppositional-defiant disorder display deviant attentional processing independent of ADHD symptoms. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2006;113:685–693. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Bihari B, Kissin B. Event-related brain potentials in boys at risk for alcoholism. Science. 1984;225:1493–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.6474187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Reich T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Blangero J, Bloom FE. Quantitative trait loci analysis of human event-related brain potentials: P3 voltage. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1998;108:244–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(98)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat EM, Malone SM, Williams WJ, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Decomposing delta, theta, and alpha time-frequency ERP activity from a visual oddball task using PCA. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;64:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat EM, Nelson LD, Steele V, Gehring WJ, Patrick CJ. Externalizing Psychopathology and Gain/Loss Feedback in a Simulated Gambling Task: Dissociable Components of Brain Response Revealed by Time-Frequency Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:352–364. doi: 10.1037/a0022124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat EM, Williams WJ, Gehring WJ. Decomposing ERP time-frequency energy using PCA. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:1314–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins CA, MacKay S, Clark W, Fein G. Event-related potential evidence for frontal cortex effects of chronic cocaine dependence. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:472–485. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RM, McCrary JW. EP component identification and measurement by principal components-analysis. Brain and Cognition. 1995;27:288–310. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Tang Y, Rangaswamy M, Wang JC, Almasy L, Foroud T, et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in a glutamate receptor gene (GRM8) with theta power of event-related oscillations and alcohol dependence. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2009;150B:359–368. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Wu S, Rostamkhani M, McGue M, Iacono WG. Role of clolinergic muscarinic 2 receptor (CHRM2) gene in cognition. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:10–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L, Bauer L, Kuperman S, Porjesz B, O’Connor S, Hesselbrock V, Begleiter H. Frontal P300 decrements, alcohol dependence, and antisocial personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;47:1064–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E. Neurophysiological correlates of cognitive development: changes in long-latency event-related potentials from childhood to adulthood. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1978;45:468–482. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(78)90291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Sejnowski T, Makeig S. Enhanced detection of artifacts in EEG data using higher-order statistics and independent component analysis. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiralp T, Ademoglu A, Istefanopulos Y, Basar-Eroglu C, Basar E. Wavelet analysis of oddball P300. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2001;39:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Aliev F, Kramer J, Wang JC, Hinrichs A, Bertelsen S, Bierut L. Association of CHRM2 with IQ: converging evidence for a gene influencing intelligence. Behavior Genetics. 2007;37:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin E, Heffley EF. Multivariate analysis of event-related potential data: A tutorial review. In: Otto D, editor. Multidisciplinary perspectives in event-related brain potential research. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1978. pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Euser AS, Arends LR, Evans BE, Greaves-Lord K, Huizink AC, Franken I. The P300 event-related brain potential as a neurobiological endophenotype for substance use disorders: A meta-analytic investigation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;36:572–603. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, Iacono WG, Doyle AE. Characteristics associated with the persistence of antisocial behavior: Results from recent longitudinal research. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 1997;2:101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Moss HB, Martin CS, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Executive cognitive functioning predicts reactive aggression in boys at high risk for substance abuse: a prospective study. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1996;20:740–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Tarter RE. Executive cognitive functioning and risk for substance abuse. Psychological Science. 1999;10:203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CS, Malone SM, Bernat EM, Iacono WG. Relationship between the P3 event-related potential, its associated time-frequency components, and externalizing psychopathology. Psychophysiology. 2010;47:123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CS, Malone SM, Iacono WG. Brain electrophysiological endophenotypes for externalizing psychopathology: a multivariate approach. Behavior Genetics. 2010;40:186–200. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9343-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CS, Malone SM, Iacono WG. Is the P3 amplitude reduction seen in externalizing psychopathology attributable to stimulus sequence effects? Psychophysiology. 2012;49:248–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada M, Porjesz B, Chorlian DB, Begleiter H, Polich J. Auditory P3a deficits in male subjects at high risk for alcoholism. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:726–738. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RJ, Bernat EM, Patrick CJ. Externalizing psychopathology and the error-related negativity. Psychological Science. 2007;18:326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Bernat E, Malone SM, Iacono WG, Patrick CJ, Krueger RF, McGue M. Genes mediate the association between P3 amplitude and externalizing disorders. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, McGue M, Patrick CJ. Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders: A twin-family study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Locke J, Zezza N, Kaplan B, Neiswanger K, Steinhauer SR, Xu J. Genetic association between reduced P300 amplitude and the DRD2 dopamine receptor A1 allele in children at high risk for alcoholism. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43:40–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Locke J, Steinhauer SR, Konicky C, Lowers L, Connolly J. Developmental delay in P300 production in children at high risk for developing alcohol-related disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:970–981. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Steinhauer SR, Locke-Wellman J, Ulrich R. Childhood risk factors for young adult substance dependence outcome in offspring from multiplex alcohol dependence families: a prospective study. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Malone SM, McGue M. P3 event-related potential amplitude and the risk for disinhibitory disorders in adolescent boys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:750–757. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM. Developmental endophenotypes: Indexing genetic risk for substance abuse with the P300 brain event-related potential. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;4:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota Twin Family Study. Twin Research. 2002;5:482–487. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Pojesz B, Almasy L, et al. Linkage and linkage disequilibrium of evoked EEG oscillations with CHRM2 receptor polymorphisms: Implications for human brain dynamics. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;53:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Porjesz B, Chorlian D, Rangaswamy M, Kamarajan C, Padmanabhapillai A, Begleiter H. S-transform time-frequency analysis of P300 reveals deficits in individuals diagnosed with alcoholism. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117:2128–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarajan C, Porjesz B, Jones KA, Choi K, Chorlian DB, Padmanabhapillai A, Begleiter H. The role of brain oscillations as functional correlates of cognitive systems: a study of frontal inhibitory control in alcoholism. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;51:155–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarajan C, Porjesz B, Jones KA, Choi K, Chorlian DB, Padmanabhapillai A, Begleiter H. Alcoholism is a disinhibitory disorder: neurophysiological evidence from a Go/No-Go task. Biological Psychology. 2005;69:353–373. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsanis J, Iacono WG, McGue MK. The association between P300 and age from preadolescence to early adulthood. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1996;24:213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(96)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Rounsaville BJ. Sensitivity of psychiatric diagnosis based on the best estimate procedure. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1225–1227. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Scholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weisman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodlogical study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]