Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To establish the value of MRI in targeting re-biopsy for undiagnosed prostate cancer despite multiple negative biopsies, and determine clinical relevance of detected tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

38 patients who underwent MRI after 2 or more negative biopsies due to continued clinical suspicion, and later underwent TRUS-guided biopsy supplemented by biopsy of suspicious areas depicted by MRI were identified. Diagnostic performance of endorectal 3T MRI in diagnosing missed cancer foci was assessed using biopsy results as the standard of reference. Ratio of positive biopsies using systematic versus MRI-prompted approaches was compared. Gleason scores of detected cancers were used as surrogate for clinical relevance.

RESULTS

34% of patients who underwent MRI before re-biopsy had prostate cancer on subsequent biopsy. The positive biopsy yield with systematic sampling was 23% versus 92% with MRI-prompted biopsies(p<0.0001). 77% of tumors were detected exclusively in the MRI-prompted zones. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of MRI to provide a positive biopsy were 92%, 60%, 55%, 94% and 71%, respectively. The anterior gland and apical regions contained most tumors; 75% of cancers detected by MRI-prompted biopsy had Gleason score≥7.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinically relevant tumors missed by multiple TRUS-guided biopsies can be detected by a MRI-prompted approach.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate biopsy is indicated in the evaluation of men with an increased prostatespecific antigen (PSA) or abnormal digital rectal exam (DRE). A systematic prostate sampling with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided needle biopsy is the standard of care for these men . Following a negative biopsy, patients with a persistently elevated PSA, low free PSA, high PSA velocity or a histologic finding with increased suspicion (e.g. atypia) may undergo a repeat prostate biopsy[1].

Cancer detection rates on repeat prostate biopsy are low. Once a patient has had 2 negative biopsy sessions, the positivity rate of subsequent biopsies continues to decline[2]. Although the issue of whether obtaining more biopsy cores detects more tumors with lower-risk characteristic remains controversial[3], repeat biopsies usually comprise a greater number of cores. This approach is associated with increased cost and patient morbidity[4], and significant cancers are still missed[3].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may facilitate identification of a suspicious area to determine which subjects with prior negative biopsy should be re-biopsied[5, 6]. More recently, investigators have also shown the value of MRI before initial TRUS-guided prostate biopsy[7, 8]. Biopsies based on MRI findings have been approached with several strategies: (a)MRI-prompted biopsies, in which the MRI data is used by the operator to target a designated area during a subsequent TRUS-guided biopsy; (b)MRI data fused to ultrasound images during TRUS-guided biopsy, to further assist in the targeting, and (c)direct MRI guidance with a specialized MRI-compatible prostate biopsy device.

The goals of this study are (a)to determine the value of endorectal 3T MRI in defining areas to be targeted during TRUS-guided prostate re-biopsy of patients with clinical suspicion for undiagnosed cancer, and (b)to establish if such detected tumors are clinically relevant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This IRB-approved and HIPAA compliant study consisted of a retrospective analysis of a single institution prostate MRI cohort. Patients who underwent 3T MRI with endorectal coil for unidentified prostate cancer despite multiple (2 or more) prior negative biopsies were included in this study. To meet eligibility criteria, TRUS-guided prostate biopsy complemented with concurrent biopsy of concerning areas depicted by pre-biopsy MRI was required. All men were referred for MRI because of PSA>4 ng/mL, PSA velocity>0.75 ng/mL/year or equivocal histopathology from previous biopsy. Patient demographics, gland size as measured by MRI, PSA values (PSA at the time of the MRI, PSA density, PSA velocity and percentage of free PSA), biopsy details (number of prior negative biopsies, number of cores on prior and latest biopsy, number of MRI-prompted biopsy cores), and pathology findings (biopsy results, including tumor presence, location and Gleason score) were collected from medical records.

MRI protocol and interpretation

MRI protocol consisted of T2-weighted and T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) images using endorectal coil (MR Innervu, Medrad, Pittsburg, PA) in a 3T scanner (Genesis Signa LX Excite, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with a gradient strength of 30 mT/m and a slew rate of 120 mT/m/ms.

T2-weighted imaging consisted of transverse and coronal fast spin-echo images obtained from below the prostatic apex to above the seminal vesicles with the following parameters: repetition time/echo time (effective) of 4,500–7600/165 ms, 2.0–2.8 mm section thickness and no intersection gap, 3 averages, 14-cm field of view, 256×192 matrix, and no phase wrap. Axial images were oriented at a slight obliquity to be perpendicular to the posterior surface of the gland. On these images, areas of low signal intensity within the high signal intensity of a normal peripheral zone were considered suspicious for prostate cancer [9]. Due to the presence of benign hyperplastic nodules, this evaluation was more challenging in the transition and central zones.

DCE imaging relied on 3D T1-weighted spoiled gradient-echo images of the prostate in the axial plane obtained with coverage area and orientation similar to the axial T2-weighted images, repetition time/echo time of 7.1/2.1 ms, flip angle of 18°, 14-cm field of view, 256 × 224 matrix, 2.6–3.0 mm section thickness, no phase wrap, yielding a temporal resolution of 95 seconds (within which 6 identical and consecutive series are acquired). Images were acquired prior to, during, and after a bolus injection of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ) at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg of body weight followed by 20 mL saline flush administered with a mechanical injection system (Spectris, Medrad, Pittsburgh, PA) at a flow rate of 4 mL/s. Images were processed with a non-commercial software using a 3-time point pharmacokinetic model to analyze the time evolution of contrast enhancement at pixel resolution. This analysis reflects kinetic parameters. A model-based calibration map related color hue/intensity in each pixel to microvascular permeability and extracellular volume fraction. The color red indicates high microvascular permeability and low to medium extracellular volume fraction, parameters suspicious for malignancy[10]. The processed DCE images were overlaid on the anatomic T2-weighted images. Clusters of bright red pixels with more than 3 mm in maximal diameter in the peripheral zone were noted as probable or definite cancer, depending on the shape and border (ill- or well-defined). In the central and anterior portion of the gland, clusters of bright red pixels more than 5 mm which also showed an asymmetric distribution compared to the contralateral side, were ill-defined or in contact with a suspicious area in the peripheral zone, were ranked as cancer (Figure 1). Benign hyperplastic nodules were designated as well-defined nodulariform lesions in the central gland, symmetrically distributed.

Figure 1. Example of suspicious MRI findings in a patient with a large anterior tumor missed by systematic sampling but detected on the MRI-prompted biopsy.

A, Axial T2-weighted fast spin echo image of the mid-third of the prostate. Tumor is not clearly demonstrated with this sequence. B, Corresponding color-coded DCE 3D T1-weighted gradient-echo image. The large anterior tumor is easily seen as a cluster of bright red pixels (arrows) with an asymmetric distribution compared to the contralateral side. C, Whole-mount histopathology proven Gleason 4+3 cancer (area delineated by the dotted line). Note that whole-mounts were available in selected patients as part of a large clinical trial, but were not used as the gold-standard.

Each MRI study was independently interpreted by 1 of 5 dedicated fellowship-trained body MRI radiologists, during their routine clinical interpretation sessions. MRI was considered positive for cancer when suspicious findings were present on either T2-weighted or DCE imaging. MRI reports were categorized by a clinical urologist blinded to the pathology findings into 5 groups: (a)negative for cancer, (b)probably negative for cancer, (c)equivocal for cancer, (d)probably cancer, and (e)definitely cancer. These results were dichotomized into 2 groups representing a negative prediction (predicting cancer absent, groups a-c) or a positive prediction (predicting cancer present, groups d and e) for the analyses. The suspicious areas on MRI were described by anatomic location: right or left; anterior or posterior; peripheral zone or central gland; base, mid or apex. The anterior region of the prostate was defined as the area anterior to the urethra. MRI and biopsy results were then compared by location to assess for site concordance.

Biopsy procedure and evaluation

Prediction and localization of cancer by MRI were assessed by an extended post-MRI, TRUS-guided biopsy that included routine systematic sampling followed by biopsy of the suspicious areas revealed by the MRI study, during the same session. TRUS-guided biopsies were performed by 1 of 3 urologists with more than 6 years of experience in the care of prostate cancer patients, under local anesthesia (transrectal periprostatic injection of 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine). Ultrasound probe setting ranged from 5.5–8 MHz to optimize visualization based on body habitus. Core biopsies were obtained with an 18 gauge needle and biopsy gun (CR Barda Inc., Covington, GA). The number of cores obtained in both systematic sampling and in the suspicious areas detected by MRI, as well as the order in which each step was performed, varied according to the judgement of the urologist performing the procedure. Each biopsy specimen was identified according to prostate anatomic location according to sextant and anterior or posterior, the latter using a transverse line bisecting the urethra[11]. Biopsies specifically targeted by MRI findings were labeled accordingly by the urologist in the TRUS-guided biopsy procedural report. A dedicated genitourinary pathologist blinded to MRI results and with 12 years of experience in prostate studies performed the histological interpretation, determining the presence or absence of cancer, and the Gleason score for positive cases.

Statistical Analysis

The ratio of positive biopsies between systematic and MRI-prompted biopsies was assessed with z-approximation. The ratios of positive cores to total sample cores between systematic and MRI-prompted biopsies were analyzed with nonparametric signed rank test. To compare the distributions of age, number of cores before and after MRI, PSA (by the time MRI was performed), PSA density, and PSA velocity, nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used. Type-I error of 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance. Post-hoc analysis was used to assess if PSA metrics increased the accuracy of MRI to detect prostate cancer. The diagnostic performance of MRI in the detection of cancer foci missed on 2 or more previous biopsies was assessed with 5 measures: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy; along with 95% confidence interval for each measure. In addition, the assessment of potential effect modification of PSA data on MRI diagnostic accuracy was completed on 4 different PSA metrics: PSA, percentage of free PSA, PSA velocity, and PSA density. For each PSA metric, the data was divided into quartiles and the 5 diagnostic accuracy estimates of MRI and their confidence intervals were calculated. The SAS software was used to carry out all data management and statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Among 1053 patients who had MRI of the prostate in our institution between August 2003 and August 2008, 38 patients were identified with a history of 2 or more previous negative biopsy sessions (range 2–5) who underwent this prostate MRI protocol and subsequent TRUS-guided biopsy with systematic sampling complemented with cores from suspicious areas on MRI. Mean age was 64 years (range 48–77), mean PSA was 14.4 ng/mL(1.8–33.1) and the mean number of cores on the latest pre-MRI biopsy was 15(6–24). The median time lapse between the negative biopsy immediately preceding imaging and MRI was 16 months (range: 1–56 months). The median time lapse between the MRI and subsequent biopsy was 1 month (range: 1 day-22 months). Of the 38 patients, 22 had MRI findings suggestive of cancer (positive MRI) and 16 had no concerning MRI findings. All 38 patients underwent prostate biopsy despite the MRI findings.

Thirteen of the 38(34%) patients had positive biopsies, identified accordingly: 1(8%) by systematic biopsy only, 2(15%) by both systematic and MRI-prompted biopsies, and 10(77%) exclusively on MRI-prompted cores. Twelve of the 22(55%) patients with positive MRI results had site concordant cancer detected on subsequent biopsy, while 1(6%) cancer was detected in the 16 patients with ‘negative’ MRI results. In the latter case, MRI suggested cancer in the left apex; however, the only positive core was obtained in the right apex by systematic sampling. That case was considered a false negative for MRI, based on its site discordance.

Among the 13 patients with proven cancer, the number of cancers detected by MRI-prompted biopsy (12/13, 92%) exceeded the number detected by systematic biopsy (3/13, 23%; p < 0.0001). Including patients with negative biopsy results in the denominator did not alter statistical significance in the observed difference: MRI-prompted (12/38, 32%) compared to systematic biopsy (3/38, 8%; p=0.0065). The number of cases detected exclusively by MRI-prompted biopsy (10/13, 77%) was also greater than the number of cases detected exclusively by systematic biopsy (1/13, 8%) (p<0.0001).

The number of biopsy cores collected in the systematic plus MRI-prompted approach varied according to the judgement of the urologist performing the procedure (median 19, range 8–28). The proportion of biopsy cores found to have cancer was higher for cores prompted by MRI findings compared to the proportion of systematic biopsy cores found to have cancer (29/67=43.3% versus 3/177=1.7%; p=0.0034) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison between core positivity in MRI-prompted biopsied areas versus systematic sampling

| Number of positive biopsy cores |

Number of negative biopsy cores |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI-prompted | 29 | 38 | 67 |

| Systematic sampling |

3 | 174 | 177 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy results of MRI to provide a positive biopsy were 92%, 60%, 55%, 94% and 71%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of the MRI findings in comparison with the site-concordant TRUS-guided biopsy results on a per-patient basis

| Patients with a positive biopsy |

Patients with a negative biopsy |

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive MRI | 12 | 10 |

| Negative MRI | 1 | 15 |

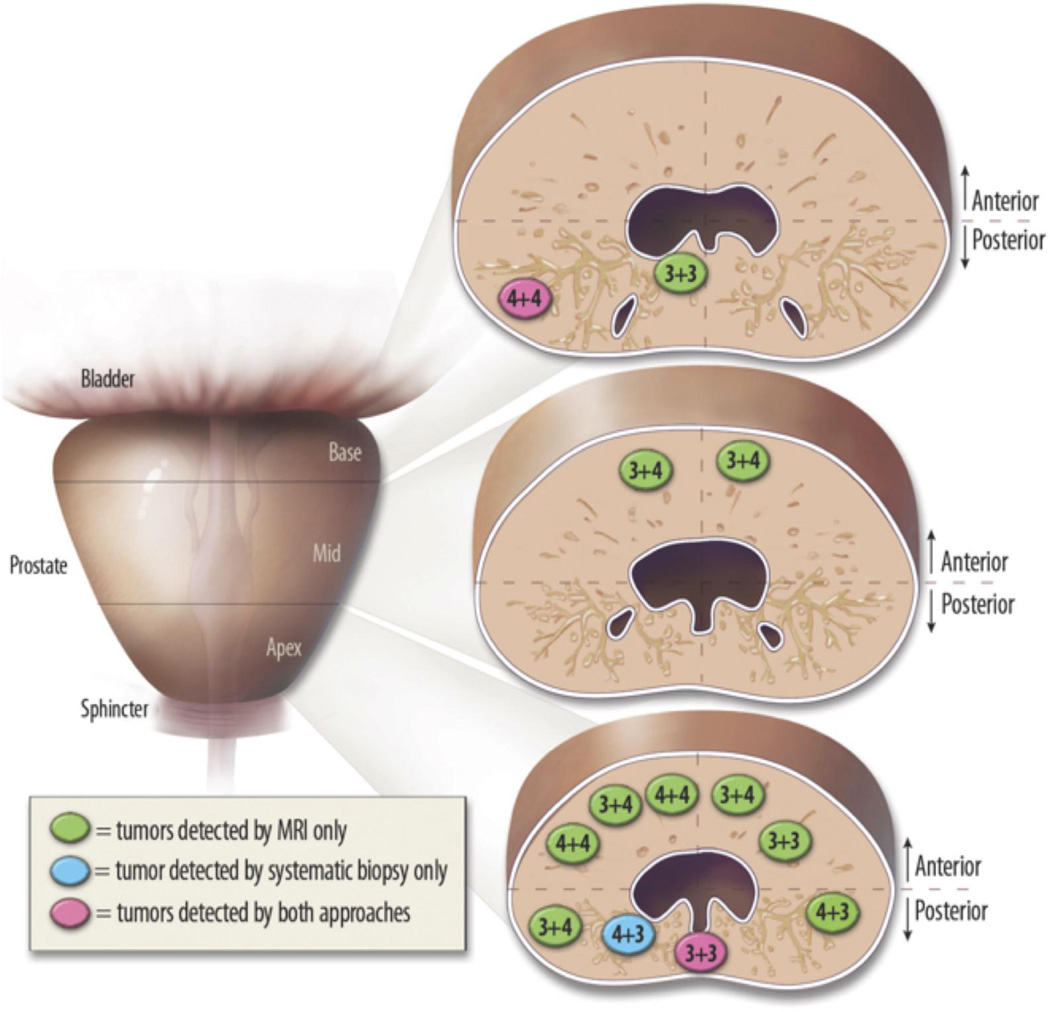

The majority of cancers detected in our series were clinically relevant. Ten of the 12 (83%) cancers detected by MRI had a Gleason 4 component, and 3 of those (25%) had a dominant 4 pattern indicating a high rate of histopathological aggressiveness[12]. Most tumors were noted in the anterior gland and in the apical region of the gland (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location and Gleason score of the detected tumors.

The vertical line separates right from left and the horizontal lines separate the anterior from posterior portions of the prostate at the base, mid-gland and apex. Green, tumors detected by MRI only; blue, tumor exclusively detected by systematic biopsy; pink, tumors detected by both approaches. While 4/13 (31%) were located in the posterior peripheral zone, there were 9/13 (69%) in the anterior gland, 9/13 (69%) in the apex, 2/13 (15%) in the mid-third of the gland and 2/13 (15%) in the base. The majority of the cancers detected (10/13, 77%) had a Gleason score ≥7.

Gland size and PSA metrics were stratified by biopsy results. Patients with positive versus negative biopsies had, respectively, smaller glands (mean volumes of 33 versus 64 cc, p=0.0053), higher PSA (mean values of 21.0 versus 12.0 ng/mL, p=0.0.0215), higher PSA density (mean values of 0.6 versus 0.2 ng/mL/cc, p=0.0006) and more rapid PSA velocity (mean values of 2.7 versus 1.2 ng/mL/year, p=0.0446) compared to patients with negative biopsies. There were no differences between patients with positive or negative biopsies in PSA doubling time or free PSA. No PSA metric improved MRI diagnostic accuracy.

DISCUSSION

The clinical challenge presented by patients with a strong suspicion of having prostate cancer yet repeatedly negative biopsies is an increasingly encountered consequence of PSA screening. The impact of the pre-released recommendations against this screening by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force[13] remains unclear. To address that challenge, a variety of biopsy strategies are available, such as the extraction of an increased number of core samples, the use of transperineal technique, or other attempts to target less commonly sampled areas[5, 14, 15]. There is still no consensus on how to address this growing patient population.

Targeted biopsies based on imaging data have been pursued as a means to improve the chances of detecting a significant cancer. Due to the optimal soft tissue contrast further augmented by the use of intravenous contrast media [16, 17], MRI has been the most successful method to date[5, 7, 18], but with variable positive biopsy yields reported[5, 19–25].

The overall cancer detection rate (34%) in this study was at the high end of the range reported by contemporary series using MRI to target biopsy sites[6], with the highest yield to our knowledge being 40%[25]. Tumors identified exclusively by MRI-prompted cores in our population outperformed other studies, 92% versus 7–54%[5]. An important consideration is that our MRI-prompted biopsy technique does not require concurrent MRI-guidance. While biopses performed under direct MR guidance are feasible and may decrease the chances of a false-negative sampling, that approach requires highly specialized equipment that is not widely available and can challenge patient throughput due to the procedural time typically being longer than most imaging studies[26]. In keeping with a more broadly applicable strategy, we also did not use specialized image fusion software to facilitate MRI-TRUS co-registration. Such software is improving and holds promise for future gains in positive biopsy yield.

Twenty-two patients with MRI findings suggestive of tumor underwent both MRI-prompted and systematic biopsies. Each patient served as his own control to assess comparative efficacy. To minimize previously reported limitations in site specificity[23], location concordance (i.e., agreement with anatomic location as follows: right or left; anterior or posterior; peripheral zone or central gland; base, mid or apex) was required for MRI-prompted biopsy positive yield. The criterion for at least 2 prior negative biopsy sessions and the large number of cores sampled prior to the MRI-prompted procedures resulted in negative enrichment of this study population and differentiates our study from others[27, 28]. Furthermore, all positive cases were DRE negative. Thus, the positive biopsy yield of this study, 34% across the entire cohort, 55% across the cohort with suggestive MRI findings, and the 77% rate of positive cancer cases uniquely detected with MRI, are strong indicators of the utility of the approach described herein.

To our knowledge, this is the first cohort of patients with at least 2 prior negative biopsies who also underwent both TRUS-guided biopsy approaches: MRI-prompted and systematic sampling. In our series, the majority of cancers detected were clinically relevant. This might represent a selection bias derived from the questionable diagnostic performance of MRI in low grade and/or small volume tumors[29]. If MRI has such a bias an assessment of the associated merits and limitations for patient care will be needed. Additionally, tumors were predominantly located in the anterior gland and, of those, more were in the apical region of the gland (Figure 2). These regions are typically undersampled with traditional biopsy approaches. The high percentage of anterior and apical cancers in our series of patients with 2 or more negative biopsies is concordant with the findings of others[5, 28, 30].

Among this selected population of patients with high PSA and multiple negative biopsies, smaller glands were associated with increased risk of positive biopsy on subsequent biopsy. This supports evidence for elevated PSA density as a risk factor for prostate cancer in men with PSA 4–20 ng/mL[31]. However, no PSA metric including PSA density, improved MRI diagnostic accuracy. This possibly results from an underpowered study for that assessment when the cohort is separated into quartiles.

Limitations of this study are the small number of patients and the use of biopsy instead of prostatectomy as the standard of reference. While it has been suggested that biopsies performed by individuals with knowledge of the MRI results could bias the operator away from the MR suggestive regions during the systematic sampling[5], it is noteworthy that the majority of the MRI detected cancers encountered in our series occurred in those areas that are typically undersampled with standard biopsy procedures. Since the MRI-prompted biopsies are based on positive MRI findings, complete data on false-positives is available. However, if MRI does not detect a suspicious region, that cancer may not get sampled during the random or targeted biopsies, limiting our ability to determine the true rate of false-negatives without prostatectomy specimens as the gold-standard. Therefore, this may result in a falsely inflated overall accuracy.

Also of note, our study relied on MRI interpretation by dedicated fellowship-trained body MRI radiologists and the use of a low temporal, high spatial resoultion protocol coupled with specialized software to facilitate the interpretation of DCE data sets. The extent of which this impacts diagnostic performance is unknown and while high temporal resolution approaches seem to be in vogue at present the issue is not without controversy[32]. Although subspecialized radiologists and post-processing software are becoming more widely available, these results may have limited applicability to other scenarios. However, one differential in our study was that MRI interpretation took place in the prospective clinical routine setting, instead of the typical “ad hoc” retrospective consensual analysis by multiple readers. The latter has some appeal as being scientifically rigorous but is less applicable to clinical reality.

In an attempt to maintain the MRI protocol concise and reproducible, our investigation did not include spectroscopic imaging[33]. Furthermore, this study was performed as part of a large clinical imaging trial in which the protocol was fixed prior to the more widespread use of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and therefore this sequence – that may offer additional information [34–36] – was not included.

Another limitation of our study is the lack of standardization regarding the number of cores obtained during the standard TRUS-guided and the MRI-prompted biopsies. Although less rigorous from a methodological perspective, this reflects the diverse clinical practices of different physicians performing prostate biopsies. By classifying the MRI findings into 5 different categories and subsequently grouping these in a dichotomized fashion, we reasonably, but arguably, somewhat arbitrarily divided the level of suspicion arising from the MRI findings. This can have an impact on the diagnostic performance measured for MRI-prompted biopsies. Furthermore, we chose one among different definitions of clinically significant tumors, and other interpretations of this term could lead to different results.

Our description of site concordance is somewhat qualitative and newer techniques such as fusion of MRI data to US data[37] as well as biopsy performed under direct MR guidance can improve the confidence of site concordance[26]. An alternative approach to this patient population could involve an attempt to routinely sample the apex and anterior gland more intensively but this would occur at the risk of increased morbidity and cost and a lack of evidence for its merit.

To improve further studies a larger cohort of patients can be evaluated, additional MR pulse sequences (e.g. diffusion-weighted imaging) can be assessed, a standardized biopsy protocol with operators blinded to the MRI findings could be employed and a cost-effectiveness analysis could be included. While such improvements should precede a widespread recommendation for MRI before re-biopsy in patients with clinical suspicion for undiagnosed prostate cancer, our results suggest clear benefits for patient care.

In conclusion, clinically relevant tumors missed by multiple TRUS-guided prostate biopsies can be detected by a MRI-prompted approach with a significant increased yield compared to repeat systematic sampling alone.

ACKNOWLDEGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, RO1CA116465 (NMR) and U01CA11391 (MGS). The authors also thank Glenn Katz and Pam Curry (UT Southwestern Medical Center, Illustration Services) for helping with illustrations.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- 3T

3 tesla

- DCE

dynamic contrast-enhanced

- DRE

digital rectal exam

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- TRUS

transrectal ultrasound

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Durkan GC, Greene DR. Elevated serum prostate specific antigen levels in conjunction with an initial prostatic biopsy negative for carcinoma :who should undergo a repeat biopsy? BJU Int. 1999;83(1):34–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Djavan B, et al. Repeat prostate biopsy: who how and when? A review. Eur Urol. 2002;42(2):93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scattoni V, et al. Extended and saturation prostatic biopsy in the diagnosis and characterisation of prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. European urology. 2007;52(5):1309–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashley RA, et al. Reassessing the diagnostic yield of saturation biopsy of the prostate. European urology. 2008;53(5):976–981. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrentschuk N, et al. 'Prostatic evasive anterior tumours': the role of magnetic resonance imaging. BJU Int. 2009;105(9):1231–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrentschuk N, Fleshner N. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in targeting prostate cancer in patients with previous negative biopsies and elevated prostate-specific antigen levels. BJU Int. 2009;103(6):730–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park BK, et al. Prospective evaluation of 3-T MRI performed before initial transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy in patients with high prostate-specific antigen and no previous biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(5):W876–W881. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labanaris AP, et al. Prostate cancer detection using an extended prostate biopsy schema in combination with additional targeted cores from suspicious images in conventional and functional endorectal magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2010;13(1):65–70. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claus FG, Hricak H, Hattery RR. Pretreatment evaluation of prostate cancer: role of MR imaging and 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiographics. 2004;24(Suppl 1):S167–S180. doi: 10.1148/24si045516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degani H, et al. Mapping pathophysiological features of breast tumors by MRI at high spatial resolution. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):780–782. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppie TM, et al. The clinical features of anterior prostate cancers. BJU Int. 2006;98(6):1167–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Brendler CB. Radical prostatectomy for impalpable prostate cancer: the Johns Hopkins experience with tumors found on transurethral resection (stages T1A and T1B) and on needle biopsy (stage T1C). J Urol. 1994;152(5 Pt 2):1721–1729. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou R, et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: A Review of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):762–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krongrad A, Lai H, Lai S. Variation in prostate cancer survival explained by significant prognostic factors. J Urol. 1997;158(4):1487–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borboroglu PG, et al. Extensive repeat transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy in patients with previous benign sextant biopsies. J Urol. 2000;163(1):158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sella T, et al. Suspected local recurrence after radical prostatectomy: endorectal coil MR imaging. Radiology. 2004;231(2):379–385. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloch BN, et al. Prostate cancer: accurate determination of extracapsular extension with high-spatial-resolution dynamic contrast-enhanced and T2-weighted MR imaging-initial results. Radiology. 2007;245(1):176–185. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilanova JC, et al. Usefulness of prebiopsy multifunctional and morphologic MRI combined with free-to-total prostate-specific antigen ratio in the detection of prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(6):W715–W722. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrotti M, et al. Prospective evaluation of endorectal magnetic resonance imaging to detect tumor foci in men with prior negative prostastic biopsy: a pilot study. J Urol. 1999;162(4):1314–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar V, et al. Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of prostate voxels identified as suspicious of malignancy on three-dimensional (1)H MR spectroscopic imaging in patients with abnormal digital rectal examination or raised prostate specific antigen level of 4–10 ng/ml. NMR Biomed. 2007;20(1):11–20. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pondman KM, et al. MR-guided biopsy of the prostate: an overview of techniques and a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2008;54(3):517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh AK, et al. Patient selection determines the prostate cancer yield of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging-guided transrectal biopsies in a closed 3-Tesla scanner. BJU Int. 2008;101(2):181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyersdorff D, et al. Patients with a history of elevated prostate-specific antigen levels and negative transrectal US-guided quadrant or sextant biopsy results: value of MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;224(3):701–706. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amsellem-Ouazana D, et al. Negative prostatic biopsies in patients with a high risk of prostate cancer. Is the combination of endorectal MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging (MRSI) a useful tool? A preliminary study. Eur Urol. 2005;47(5):582–586. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prando A, et al. Prostatic biopsy directed with endorectal MR spectroscopic imaging findings in patients with elevated prostate specific antigen levels and prior negative biopsy findings: early experience. Radiology. 2005;236(3):903–910. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2363040615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zangos S, et al. MR-compatible assistance system for biopsy in a high-field-strength system: initial results in patients with suspicious prostate lesions. Radiology. 2011;259(3):903–910. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roethke M, et al. MRI-guided prostate biopsy detects clinically significant cancer: analysis of a cohort of 100 patients after previous negative TRUS biopsy. World J Urol. 2011;30(2):213–218. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0675-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging targeted biopsy in men with previously negative prostate biopsy results. Journal of endourology / Endourological Society. 2012;26(7):787–791. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkham AP, Emberton M, Allen C. How good is MRI at detecting and characterising cancer within the prostate? European urology. 2006;50(6):1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.025. discussion 1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JL, Ellis WJ. Improved prostate cancer detection with anterior apical prostate biopsies. Urol Oncol. 2006;24(6):492–495. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presti JC, Jr, et al. Prospective evaluation of prostate specific antigen and prostate specific antigen density in the detection of nonpalpable and stage T1C carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1996;156(5):1685–1690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon CJ, et al. Dynamic contrast -enhanced MR imaging in the evaluation of patients with prostate cancer. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2009;17(2):363–383. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinreb JC, et al. Prostate cancer: sextant localization at MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging before prostatectomy--results of ACRIN prospective multi-institutional clinicopathologic study. Radiology. 2009;251(1):122–133. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511080409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vargas HA, et al. Diffusion-weighted endorectal MR imaging at 3T for prostate cancer: tumor detection and assessment of aggressiveness. Radiology. 2011;259(3):775–784. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CK, Park BK, Kim B. Diffusion-weighted MRI at 3T for the evaluation of prostate cancer. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2010;194(6):1461–1469. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim HK, et al. Prostate cancer: apparent diffusion coefficient map with T2-weighted images for detection--a multireader study. Radiology. 2009;250(1):145–151. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2501080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marks L, Young S, Natarajan S. MRI-ultrasound fusion for guidance of targeted prostate biopsy. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23(1):43–50. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32835ad3ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]