Abstract

Divalent metal ions are crucial as cofactors for a variety of intracellular enzymatic activities. Mg2+, as an example, mediates binding of deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates followed by their hydrolysis in the active site of DNA polymerase. It is difficult to study the binding of Mg2+ to an active site because Mg2+ is spectroscopically silent and Mg2+ binds with low affinity to the active site of an enzyme. Therefore, we substituted Mg2+ with Mn2+:Mn2+ that is not only visible spectroscopically but also provides full activity of the DNA polymerase of bacteriophage T7. In order to demonstrate that the majority of Mn2+ is bound to the enzyme, we have applied site-directed titration analysis of T7 DNA polymerase using X-ray near edge spectroscopy. Here we show how X-ray near edge spectroscopy can be used to distinguish between signal originating from Mn2+ that is free in solution and Mn2+ bound to the active site of T7 DNA polymerase. This method can be applied to other enzymes that use divalent metal ions as a cofactor.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, manganese, XAFS, metal cofactor, metalloenzyme

I. INTRODUCTION

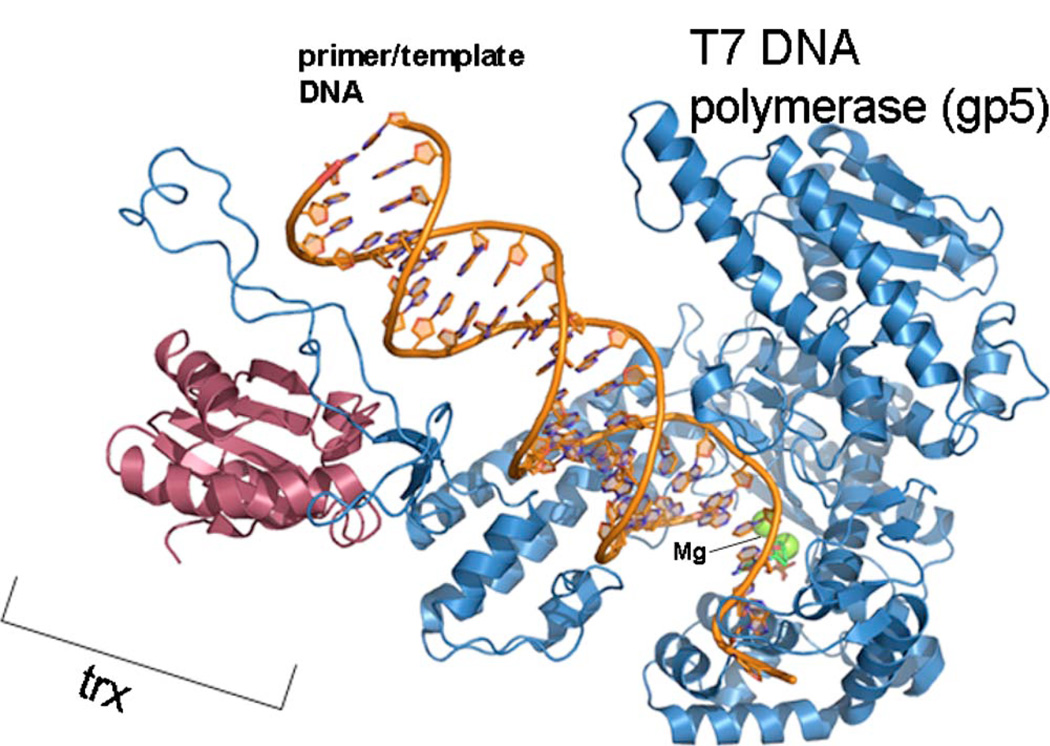

The product of gene 5 of bacteriophage T7 is a DNA polymerase (gp5) that dissociates from the DNA after catalysis of only a few cycles of polymerization of nucleotides. Hence it is designated as a polymerase with low processivity. The processivity factor, Escherichia coli thioredoxin (trx), binds tightly (5 nM) (Huber et al., 1986) in a one-to-one stoichiometry to a unique polypeptide loop (trx-binding domain ) located in the thumb subdomain of gp5 (Bedford, Tabor and Richardson, 1997). The binding of trx converts gp5 to a highly processive polymerase that polymerizes hundreds of nucleotides before dissociating from the DNA template (Hamdan et al., 2007; Tabor et al., 1987). The utilization of nucleotides in the polymerization process is mediated by divalent metal ions. Mg2+ is abundant in the cell and is usually the divalent metal ion of choice in processes involving hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates. The crystal structure of gp5 in complex with trx, a primer-template, and a nucleoside 5′-triphosphate trapped in a polymerization mode is available (Figure 1). The active site of DNA polymerase binds two metal ions. One Mg2+ stabilizes the reactive state of the bound dNTP, and a second Mg2+ takes an active role in catalysis as postulated in the two metal ion mechanism (Steitz, 1998).

Figure 1.

(Color online) Crystal structure of the bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase (PDB entry 1t8e). The DNA polymerase (gp5) and the host encoded processivity factor trx are indicated. The figure was created using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

Mg2+ shields the negatively charged phosphate groups of the nucleotide triphosphate to avoid repulsion of the nucleophile during catalysis (Jencks, 1987). Mg2+ may also be involved in increasing the reactivity of the attacked phosphor by withdrawing electrons and stabilizing the leaving phosphate. Mg2+ also forms a bridge between the nucleophile (water) and the nucleoside triphosphate. Mg2+ may also induce structural rearrangements in the active site required for precise positioning of the substrate. Probing Mg2+ using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAFS) is technically difficult (for review see Akabayov et al., 2005). Therefore, since Mg2+ is spectroscopically silent, one approach to obtain information about the active site metal is its substitution by spectroscopically “visible” metal ions (Akabayov et al., 2005). However, it is a challenge to study metal binding sites when the metal cofactors are weakly bound.

XAFS serves as a tool for directly monitoring the binding of Mn2+ to the active site of T7 DNA polymerase. XAFS provides high resolution structural and electronic information about a metal site by measuring the transition from core electronic states of the metal to excited electronic or continuum states. X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES), spectral analysis near the electronic transition, is used to obtain information about the charge and the geometry of the metal ion (Scott et al., 1985). Previous studies on model compounds linked intensity patterns and shapes of XANES spectra to structural information on the metal binding site such as coordination number and geometry (Blumberg et al., 1976; Shulman et al., 1976; Westre et al., 1997). Thus, XANES allows the study of the binding properties of a nucleoside triphosphate when Mn2+ is in the active site of T7 DNA polymerase. However, since binding of Mn to the polymerase active site is weak (approximately 20 µM), the challenge was to verify that the signal originates from bound Mn2+ rather than from Mn2+ that is free in solution. Here we show that titration of T7 DNA polymerase to Mn-ddATP can be used as a fingerprint of the metal cofactor binding and allows the determination of the best conditions for probing the metal binding site by XAFS.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

A. Materials and reagents

Oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technology. All chemical reagents were of molecular biology grade (Sigma). Nucleotides were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Radioactive materials were purchased from Perkin-Elmer. Wild-type and genetically modified gp5 were overproduced and purified using metal free buffers as described (Tabor and Richardson, 1989).

DNA polymerase activity was measured in a reaction containing 20 nM M13 ssDNA annealed to a 24-mer primer, 40 mM tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2.75 mM MgCl2 or MnCl2, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 0.25 mM dTTP, dGTP, dCTP, and [α-32P]-dTTP (5 cpm/pmol), and 10 nM of T7 gp5/trx. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and terminated by the addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM. Aliquots of the reaction were spotted on DE-81 filters (Whatman), washed with ammonium formate, and radioactivity retained on the filters was measured.

B. Sample preparation for XAFS

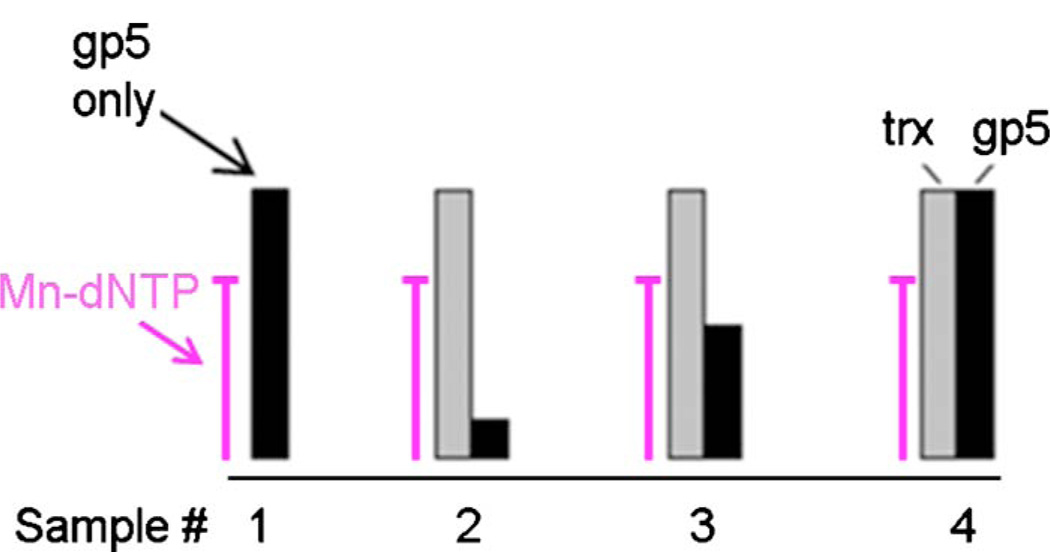

The proteins were concentrated by centrifugation using Millipore Centricons (Bedford, MA) to yield a final concentration in the sub-mM range. The DNA used in each sample contained 21-mer primer 5′-CGAAACGACGGCCAGTGCCA-3′ annealed to 26-mer template 5′-CCCCTTGGCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTCG-3′. Each sample contained 300 µM MnCl2 and dideoxy-ATP (ddATP) in a buffer of 40 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM DTT, 30% glycerol, and increasing amounts of T7 gp5 (32, 170, and 450 µM) mixed with trx (450 µM) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(Color online) Schematic representation of sample preparation. Bound nucleotide obtained upon titration of T7 DNA polymerase (gp5) above and below its binding constant to dATP (20 µM) using the binding equation (1). The four samples are depicted schematically in columns where black is the amount of DNA polymerase used, gray is the amount of trx, and the amount of Mn-ddATP is fixed as indicated (300 µM).

Binding of Mn-dNTP to T7 DNA polymerase is a single step reaction of the type A+B⇄AB. The dissociation constant is given by

where [A] and [B] are the concentrations of T7 DNA polymerase (B) and Mn-dNTP (A) and [AB] the concentration of the complex in equilibrium.

Expressing the equilibrium concentrations of the separate components in terms of initial concentrations (indicated by a subscript “0”) and the concentration of the complex

We obtain

If we wish to have×fraction of A0 in the complex AB:

then the following amount of B is required to have AB complex:

| (1) |

A0, the concentration of Mn-ddATP, was kept constant at 300 µM for all samples. KD, the dissociation constant, is 20 µM according to Patel et al., 1991. Therefore, to obtain 90% binding of Mn(x=0.9), 300 µM Mn-ddATP (A0) was mixed with 450-µM T7 DNA polymerase (B).

The components were mixed at 0 °C and immediately frozen in copper sample holders (10×5×0.5 mm3) covered with Mylar using liquid nitrogen.

C. XAFS data collection

XAFS data collection was performed at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, beam line X3B. The spectra were recorded as previously described (Akabayov et al., 2009). Specifically, the Mn K-edge was measured in a fluorescence mode at cryogenic temperature (20 K). The beam energy was selected using a flat Si (III) crystal monochromator with an energy resolution (dE/E) :~2×10−4. The incident beam intensity was recorded using a transmission ion chamber and the fluorescence signal from the sample was measured using a 13- element germanium detector. For the calibration of the X-ray energy, the transmission signal of a Mn foil reference was measured simultaneously with the sample fluorescence. For each sample, several scans were collected to obtain a total of 1×106 counts. The beam position was varied for each scan to minimize radiation damage and samples were checked for visual signs of photoreduction (burn marks) after each scan (30 min). Further protection of the sample from radiation damage was obtained by addition of DTT to the sample buffer serving as a free radical scavenger. In addition, the protein sample was exposed to X-ray under cryogenic temperature. Examination of the samples on SDS page after the exposure to the X-ray beam revealed no evidence of protein degradation caused by radiation damage (not shown).

D. XAFS data processing and analysis

The average Mn K-edge adsorption coefficient µ(E) was obtained after 4–5 independent XAFS measurements for each sample. To calibrate the X-ray energy, all spectra for each sample were aligned using the first inflection point of a reference Mn foil X-ray absorption spectrum (6539 eV). The measured intensities were converted to µ(E) and the smooth pre-edge function was subtracted from the spectra to get rid of any instrumental background and absorption from other atomic edges. The data [µ(E)] were normalized and a smooth postedge background function was removed to approximate µ(E) in order to align all spectra. All XAFS data processing steps were performed using athena software embedded in the ifeffit analysis package (Newville, 2001).

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

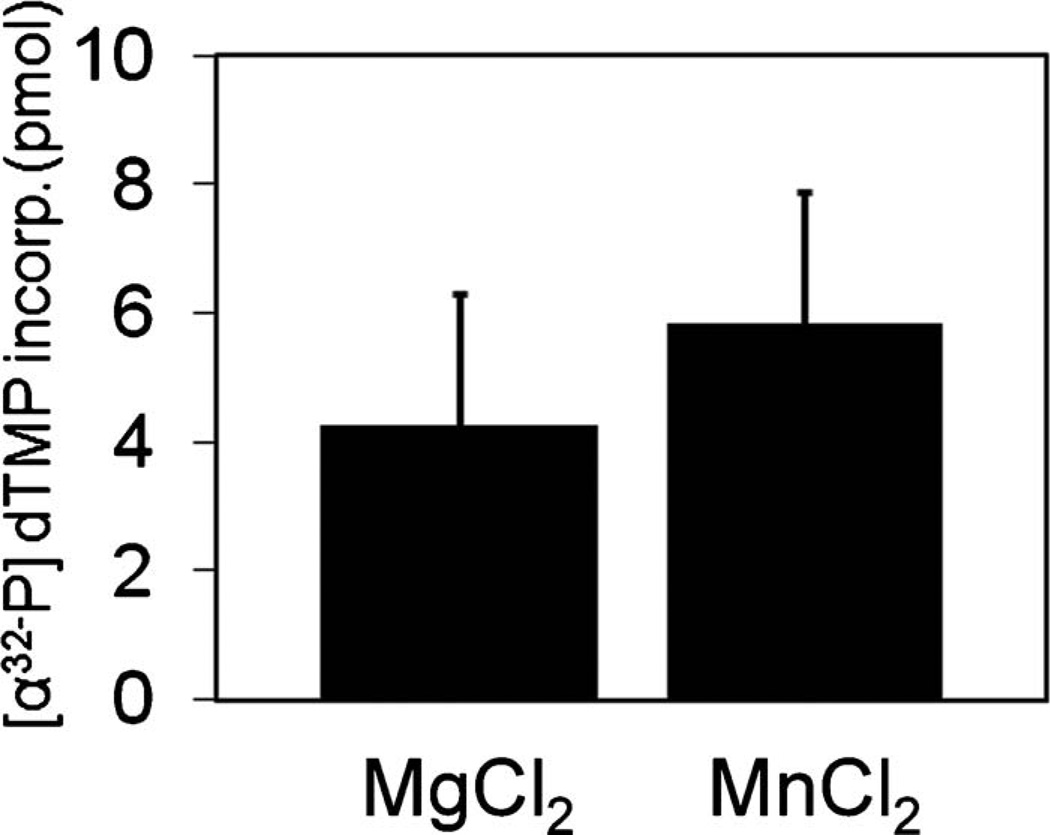

Metal ions that serve as cofactors for enzymatic activities have a lower binding affinity compared to structurally bound metal ions. With a metal ion concentration of >300 µM, which is necessary to obtain XAFS signal, a relatively high concentration of protein is required to ensure that majority of Mn2+ ions are bound and protein solubility is a limiting factor. Consequently, it is important to have a method that distinguishes bound metal ions from those that are free in solution. To study the binding properties of the active site of T7 DNA polymerase, we have substituted Mg2+ with Mn2+. Mn2+ is not only spectroscopically “visible” but Mn2+ can also bind to T7 DNA polymerase to yield a fully active enzyme (Figure 3). We used a site-directed titration analysis with XAFS to demonstrate that the majority of the Mn2+ ions are bound to dNTP to form a stable protein-dNTP complex.

Figure 3.

Effect of substitution of Mg with Mn on T7 DNA polymerase activity. DNA polymerase activity was measured in a reaction containing 40 mM tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2.75 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 0.25 mM dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, and [α-32P] dTTP, 20 nM primed M13 DNA, and 10 nM T7 gp5/trx. After incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, the amount of [α32-P] dTMP incorporated into DNA was measured.

Binding of a chain terminating nucleotide dideoxy-ATP (ddATP) to the active site of gp5 was achieved by titration of gp5/trx above and below its binding constant to dNTP, Kd =20 µM (Patel et al., 1991). The protein/nucleotide ratios were calculated based on the desired complex concentration and the equilibrium dissociation constant for the proteinligand binding equilibria of the type: A+B⇄AB (see Sec. II).

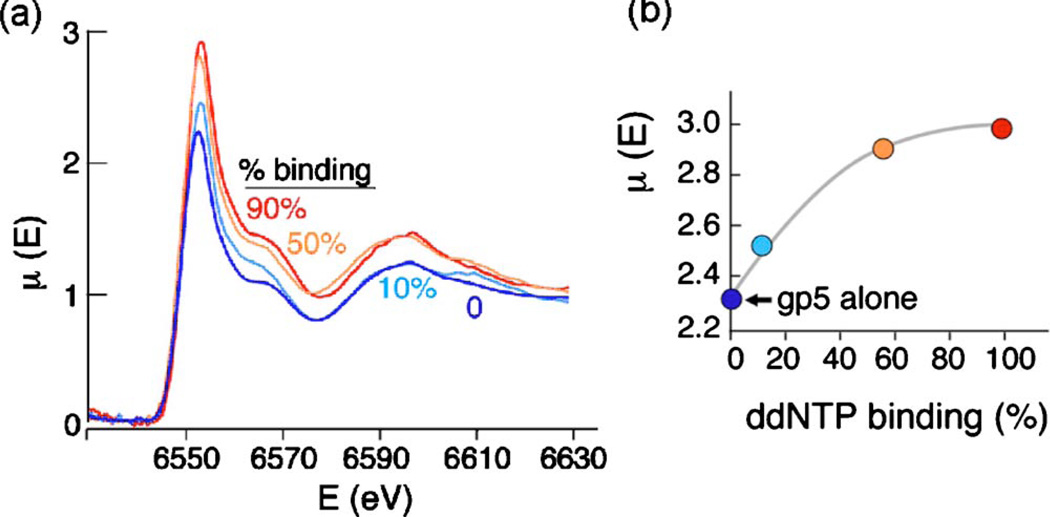

The XANES analysis enabled us to probe the coordination of the Mn-ddATP in the active site of gp5. The evolution of the amplitude of the X-ray absorption coefficient upon Mn-ddATP binding to T7 DNA polymerase as a function of the enzyme concentration shows that in the absence of trx (and with higher amounts of gp5), there is a low µ(E) of the near edge spectrum (Figure 4, blue, gp5 alone). The signal of ddATP binding to the active site of gp5 evolved when increasing amounts of gp5 were added to a fixed amount of trx (Figure 4, cyan, orange, and red circles, respectively).

Figure 4.

(Color online) (a) Site directed titration XANES analysis of T7 DNA polymerase above and below its binding constant to Mn-dNTP [according to Eq. (1), experimental]. Each sample contained the same concentration of Mn-dNTP (300 µM) and increasing concentrations of T7 DNA polymerase (blue: 0 µM; light blue: 32-µM; orange; 170-µM; red: 450-µM) mixed with E. coli thioredoxin (450-µM) (see Figure 2). (b) A typical binding curve when each point in this curve represents the maximum amplitude value of each XANES spectrum vs. dNTP binding [color coding as in (a)].

Probing metal binding sites of enzymes by XAFS is one approach to explain the changes that occur in critical metal centers during catalysis. In XAFS, the metal is the probe for the detection of sensitive changes in its local structure as well as its intrinsic chemical properties. Spectral analysis near the electronic transition, XANES, provides information on the charge state and the geometry of the metal (Scott et al., 1985). Studies on model compounds showed that preedge shapes and intensity patterns can be correlated with coordination number and geometry (Blumberg et al., 1976; Shulman et al., 1976; Westre et al., 1997). We titrated T7 DNA polymerase at concentrations above and below the binding constant to Mn-ddATP. Binding of Mn-ddATP to T7 DNA polymerase results in an increase of the amplitude of the corresponding XANES signal as presented in Figure 4(a). The change in amplitude of the XANES highest peak with increasing protein concentration closely resembles a typical binding curve [Figure 4(b)]. This titration analysis allowed us to probe the conditions necessary for retaining the complex ddATP bound to the active site of T7 DNA polymerase through Mn2+. This method should be applicable to any protein binding metal ions in the high µM range. Such analysis is crucial when measuring the binding properties of the active site of an enzyme with low binding affinity to metal ions.

IV. CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrate a unique application of XAFS for characterizing the binding properties of metal ions to proteins especially when the binding affinity of the protein to the metal ion is low. The titration analysis presented here allows the differentiation of signal originating from bound or free metal ions and, subsequently, determination of the best sample conditions for the study of metal ions in the binding site. This application simplifies data analysis and eliminates the need for data manipulations such as principal component analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Sullivan, Jennifer Bohon, Donald Abel (Beamline X-3B, National Synchrotron Light Source, Upton, NY) for technical support. This publication was made possible by the Center for Synchrotron Biosciences grant, P30-EB-009998, from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Biogineering (NIBIB). This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. GM54397.

References

- Akabayov B, Doonan CJ, Pickering IJ, George GN, Sagi I. Using softer X-ray absorption spectroscopy to probe biological systems. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:392–401. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505010150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akabayov B, Lee SJ, Akabayov SR, Rekhi S, Zhu B, Richardson CC. DNA recognition by the DNA primase of bacteriophage T7: A structure-function study of the zinc-binding domain. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1763–1773. doi: 10.1021/bi802123t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford E, Tabor S, Richardson CC. The thioredoxin binding domain of bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase confers processivity on Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:479–484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg WE, Eisenberger P, Peisach J, Shulman RG. X-ray absorption spectroscopy: Probing the chemical and electronic structure of metalloproteins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1976;74:389–399. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3270-1_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan SM, Johnson DE, Tanner NA, Lee JB, Qimron U, Tabor S, van Oijen AM, Richardson CC. Dynamic DNA helicase-DNA polymerase interactions assure processive replication fork movement. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber HE, Russel M, Model P, Richardson CC. Interaction of mutant thioredoxins of Escherichia coli with the gene 5 protein of phage T7. The redox capacity of thioredoxin is not required for stimulation of DNA polymerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15006–15012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. New York: Dover; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Newville M. IFEFFIT: interactive XAFS analysis and FEFF fitting. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2001;8:322–324. doi: 10.1107/s0909049500016964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Wong I, Johnson KA. Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of processive DNA replication including complete characterization of an exonuclease-deficient mutant. Biochemistry. 1991;30:511–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RA, Schwartz JR, Cramer SP. Effect of cyanide binding on the copper sites of cytochrome c oxidase: An X-ray absorption spectroscopic study. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1985;23:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(85)85026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman GR, Yafet Y, Eisenberger P, Blumberg WE. Observations and interpretation of X-ray absorption edges in iron compounds and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1976;73:1384–1388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.5.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz TA. A mechanism for all polymerases. Nature (London) 1998;391:231–232. doi: 10.1038/34542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor S, Huber HE, Richardson CC. Escherichia coli thioredoxin confers processivity on the DNA polymerase activity of the gene 5 protein of bacteriophage T7. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:16212–16223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor S, Richardson CC. Effect of manganese ions on the incorporation of dideoxynucleotides by bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase and Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:4076–4080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westre TE, Kennepohl P, DeWitt JG, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. A multiplet analysis of Fe K-Edge 1s f 3d pre-edge features of iron complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6297–6314. [Google Scholar]