Abstract

Background

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation for prevention of sudden cardiac death is typically deferred for 90 days after coronary revascularization, but mortality may be highest early after cardiac procedures in patients with ventricular dysfunction. We determined mortality risk in post-revascularization patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35% and compared survival to those discharged with a wearable cardioverter defibrillator (WCD).

Methods and Results

Hospital survivors after surgical (CABG) or percutaneous (PCI) revascularization with LVEF≤35% were included from Cleveland Clinic and national WCD registries. Kaplan-Meier, Cox proportional hazards, propensity score-matched survival and hazard function analyses were performed. Early mortality hazard was higher among 4149 patients discharged without a defibrillator compared to 809 with WCDs (90-day mortality post-CABG 7% vs. 3%, p=0.03; post-PCI 10% vs. 2%, p<0.0001). WCD use was associated with adjusted lower risks of long-term mortality in the total cohort (39%, p<0.0001) and both post-CABG (38%, p=0.048) and post-PCI (57%, p<0.0001) cohorts (mean follow-up 3.2 years). In propensity-matched analyses, WCD use remained associated with lower mortality (58% post-CABG, p=0.002; 67% post-PCI, p<0.0001). Mortality differences were not attributable solely to therapies for ventricular arrhythmia. Only 1.3% of the WCD group had a documented appropriate therapy.

Conclusions

Patients with LVEF≤35% have higher early compared to late mortality after coronary revascularization, particularly after PCI. As early hazard appeared less marked in WCD users, prospective studies in this high risk population are indicated to confirm whether WCD use as a bridge to LVEF improvement or ICD implantation can improve outcomes after coronary revascularization.

Keywords: survival, coronary revascularization, left ventricular dysfunction, percutaneous coronary intervention, wearable defibrillator

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) is typically deferred for three months after revascularization and 40 days after myocardial infarction (MI) based on primary prevention randomized studies that typically excluded such patients from randomization,1-3 randomized ICD trials that failed to show a total mortality benefit early after MI,4, 5 and Medicare reimbursement restrictions. Nevertheless, SCD risk is typically higher early after major cardiac events.6 The VALIANT study7 showed that patients with reduced systolic function were at highest risk for SCD in the first 30 days after MI. In preliminary data from our institution, we similarly observed higher early mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).

Despite this risk, ICDs do not improve overall survival early after MI; lower rates of arrhythmic deaths appear counterbalanced by more non-arrhythmic deaths, as in the DINAMIT and IRIS trials.4, 5 Similar phenomena could be operative after coronary revascularization. The only trial of ICD placement at time of CABG showed no survival benefit, although this early study (CABG-PATCH) utilized now obsolete epicardial abdominal ICD systems.8 However, as our preliminary data showed substantial early mortality, we sought to determine if a non-invasive strategy that could ameliorate early SCD risk might improve overall survival.

The wearable cardioverter-defibrillator (WCD) is an external device capable of automatic ventricular tachyarrhythmia detection and defibrillation. The device can improve sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) survival over reliance on emergency medical services.9 Survival is comparable to that of patients with ICDs.10 The WCD is often used during transition periods as a bridge to LV improvement or ICD implantation.11

We aimed to determine in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%: 1) whether mortality risk is different early compared to late after discharge from CABG or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); and 2) if survival is different in patients discharged with or without a WCD after CABG or PCI.

Methods

Patients for this retrospective observational parallel cohort study were obtained from prospectively collected registries of all patients who undergo cardiac surgery and PCI at the Cleveland Clinic and from a national database of all patients issued a WCD post-market release in the United States. The study period for inclusion was 8/1/2002 to 12/31/2009.

Study Population

No WCD Revascularization Subjects

Patients were included if they underwent CABG or PCI at the Cleveland Clinic during the study period, had LVEF≤35%, and survived to hospital discharge. Exclusion criteria included presence of a preexisting ICD, ICD implantation before discharge after CABG or PCI, WCD issued at discharge, or absence of a Social Security number to determine Social Security Death Index (SSDI) mortality status. Patients were not excluded for concomitant procedures at the time of CABG. Subjects were divided into specified CABG and PCI subgroups. Subjects were studied under PCI and cardiac surgery registries approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

WCD Revascularization Subjects

All patients issued a WCD (LifeVest®, ZOLL, Pittsburgh, PA) post-market release in the U.S. are entered into a database maintained by the manufacturer for regulatory, reimbursement, and tracking purposes. The database includes indications, demographics, and events. All patients signed consent to use their data for quality monitoring, health care operation activities, and/or research. The study included patients who wore the WCD for any time during the study period with the indication being post-CABG or PCI with LVEF≤35%.

Outcomes Follow-Up

Mortality

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, determined from the SSDI. A 6-month censor period was incorporated to adjust for lags in death reporting. Date of censoring for all observations was 3/8/2010. SSDI information was provided for WCD cohorts by ZOLL. The national WCD database also collected deaths during WCD use. ZOLL data was available for only 3 years, so cut-offs for graphical presentation are 3 years.

Events during WCD Use

WCD function, arrhythmia criteria, and event and outcome determination have been described previously.10 All potentially lethal arrhythmias (sustained VT/VF or asystole) occurring within 24 hours were considered a single SCA event. Two-lead electrocardiograms from all shocks and asystole events were reviewed by 2 authors (SJS, ETZ) and differences adjudicated by consensus with the senior author (MKC). There was 100% concordance to logged events.

Statistical Analyses

Data were stratified by procedure (CABG, PCI) and WCD use. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (15th, 85th percentile) unless otherwise indicated. These percentiles were used as they are similar to ±1SD and encompassed 70% of the data. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used for continuous data. Categorical data are displayed as frequencies and percentages and analyzed with Chi-square or Fisher exact tests. All analyses used SAS statistical software (SAS v9.1; SAS, Inc., Cary, NC). Results were considered statistically significant for two-sided p values<0.05.

Survival analyses

Survival was assessed non-parametrically by the Kaplan-Meier method and parametrically by a multiphase hazard model. The parametric model was used to resolve a number of phases of instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) and to estimate shaping parameters.12 Cox proportional hazard models were used to adjust for covariates. Available baseline covariates common to the WCD and Cleveland Clinic databases included age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and LVEF. To adjust for potential improvement in survival related to improved procedural techniques, we adjusted for the time interval since 1/1/2002 and index revascularization procedure. To better understand the differences in early versus late mortality, we further performed survival analysis with all outcomes censored at 90 days and another analysis where all events occurring within 90 days of revascularization were excluded and time zero was reset to 90 days after revascularization.

Propensity score matched analyses

To further reduce influences of potential selection bias on the outcome, we performed propensity score matched survival analysis and comparison of the WCD and No WCD groups. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation technique13 was employed to impute missing values with 5-fold multiple imputation using PROC MI (SAS v9.1). Based on each imputed complete dataset, propensity scores were estimated for each patient. The average of the propensity scores over the 5 imputed complete data sets yielded the final estimate of the propensity scores. Variables were excluded from analysis if over 15-20% was missing.

Preoperative variables and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify factors associated with WCD use in the comparisons. As few variables were common to both databases, propensity models included all common variables (age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, LVEF, and procedure date years since 1/12002). A propensity score was calculated for each patient by solving the propensity model for probability of receiving a WCD. The C-statistic was calculated to assess the goodness of fit measurement of the logistic model. Ranging from 0.5-1.0, the C-statistic describes how well the model discriminates between dichotomous observations (WCD use vs. no WCD use) with higher values indicating a better predictive model. Using only the propensity score, WCD cases were matched to No WCD cases using a greedy matching strategy.12, 14, 15 For the greedy matching algorithm, one at a time, propensity scores of the WCD are matched with the closest non-WCD propensity score within a distance of 0.1. After a match has been found, then that pair is removed from the patient list. This is continued until all cases are matched or there are no longer any candidate non-WCD scores that fall within the 0.1 distance parameter. WCD cases whose propensity scores deviated by more than 0.1 from those of non-WCD cases were considered unmatched. Separate propensity score matched analyses were performed for CABG and PCI patients. The decomposition of time-varying hazard phase analyses has been previously published.12

Results

At the Cleveland Clinic 4149 patients who underwent CABG (N=2198) or PCI (N=1951) met entry criteria and were included into the No WCD group. In the national registry, 809 patients met criteria and were included into the WCD group. Of these, 514 patients had revascularization type recorded (226 CABG, 288 PCI). Patients without a record of method of revascularization were excluded from sub-group analyses.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

In the total cohort (N=4958) and in the CABG cohort (N=2424), WCD patients were younger with more males, diabetes mellitus and lower LVEF than in No WCD patients (Table 1). Median and mean durations of WCD use after CABG were 72 (22, 113) and 79±69 days. In the PCI cohort (N=2239), WCD users were younger with lower LVEF but less diabetes mellitus. Median and mean durations of WCD use after PCI were 61 (2, 111) and 81±183 days. Across all cohorts, times since 1/1/2002 to index revascularization procedures were longer in WCD groups. Supplemental Table 1 shows targeted vessels and MI status for the No WCD PCI group, and Supplemental Table 2 reports concomitant procedures in the No WCD CABG group. These data were not available for the WCD cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Continuous variables reported as mean±standard deviation and median (15th, 85th percentiles).

| Total Cohort, N=4958 | CABG, N=2424 | PCI, N=2239 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All N (%) | WCD N=809(%) | No WCD N=4149(%) | P value | WCD N=226(%) | No WCD N=2198(%) | P value | WCD N=288(%) | No WCD N=1951(%) | P value | |

| Age, years | 66.6±11.6 | 63.6±11.9 | 67.2±11.4 | <0.0001 | 63.7±11.1 | 67.5±10.7 | <0.0001 | 63.2±12.8 | 66.9±12.3 | <0.0001 |

| 67.6 (54,78.5) | 64 (51.2,76.6) | 68.3 (55,79) | 63.8 (51.4,76.8) | 68.4 (55.9,78.5) | 63.6 (50,77.1) | 68 (54,79) | ||||

| Gender, female | 1234/4958(25) | 156/809(19) | 1078/4149(26) | <0.0001 | 30/226(13) | 527/2198(24) | 0.0003 | 67/288(23) | 551/1951(28) | 0.078 |

| Hypertension | 3761/4684 (80) | 431/536(80) | 3330/4148(80) | 0.94 | 125/156 (80) | 1762/2198(80) | 0.99 | 162/212(76) | 1568/1950(80) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2089/4622 (45) | 246/492(50) | 1843/4130(45) | 0.024 | 87/150(58) | 944/2179(43) | 0.0005 | 74/192(39) | 899/1951(46) | 0.045 |

| LVEF,% | 26.8±7.6 | 24.7±8.3 | 27.2±7.4 | <0.0001 | 23.5±7.7 | 27.2±8.0 | <0.0001 | 26.3±8.1 | 27.3±6.8 | 0.0044 |

| 27 (20,35) | 25 (15,33) | 30 (20,35) | 23 (15,32.7) | 25 (20,35) | 26.5 (17.5,35) | 30 (20,35) | ||||

| N=217 | N=1871 | |||||||||

| Interval from 1/1/2002 to index revascularization, years | 4.2±2.3 | 6.7±1.5 | 3.7±2.1 | <0.0001 | 6.7±1.5 | 3.6±2.2 | <0.0001 | 6.6±1.5 | 3.9±2.1 | <0.0001 |

| 4.1 (1.4,7.1) | 6.9 (5.7,7.9) | 3.5 (1.3,6.4) | 7.0 (5.7,8.0) | 3.2 (1.2,6.4) | 6.7 (5.6,7.9) | 3.8 (1.5,6.5) | ||||

Survival analyses

In the entire cohort, 1480/4958 subjects (30%) died (follow-up 3.2±2.3 years, median 2.8 years). In the No WCD group, 1399/4149 subjects (34%) died; 81/809 (10%) died in the WCD group. In the PCI cohorts, 763/1951 (39%) No WCD and 31/288 (11%) WCD patients died. In the CABG cohorts, 636/2198 (29%) No WCD and 19/226 (8.4%) WCD patients died.

Ninety-day mortality was 324/4149 (7.8%) in No WCD and 18/809 (2.2%) in WCD patients, p<0.0001. In the PCI cohorts, 90-day mortality was 189/1951 (9.7%) in No WCD and 5/288 (1.7%) in WCD patients, p<0.0001. In the CABG cohorts, 90-day mortality was 135/2198 (6.1%) in No WCD and 7/226 (3.1%) in WCD patients, p=0.064.

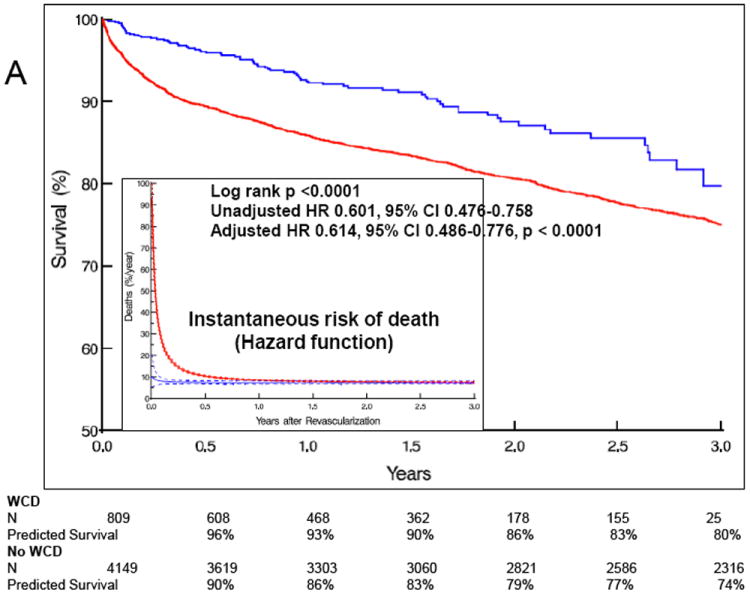

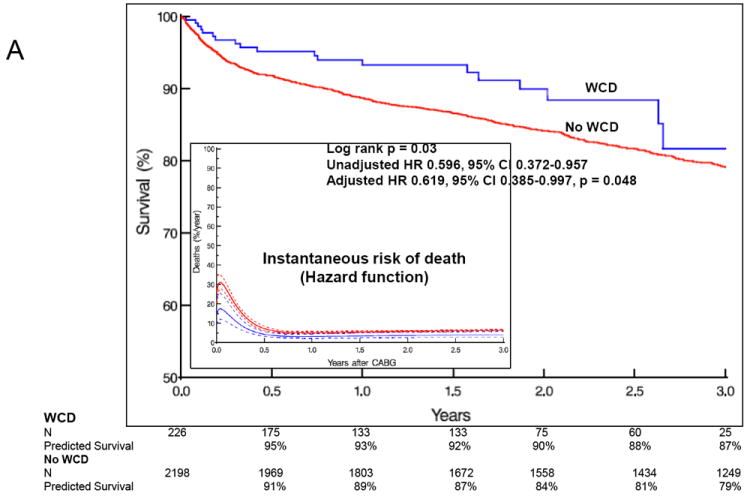

Total Cohort

In the total cohort, Kaplan-Meier survival analyses stratified by WCD use (Figure 1A) demonstrated significantly better survival in the WCD group with univariate hazard ratio (HR) 0.601, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.476-0.957, p<0.0001. Cox proportional hazards analyses (Table 2), adjusting for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes and LVEF, showed WCD use was associated with a 38.6% lower risk of long-term mortality (p<0.0001). Other predictors of long-term mortality included age, diabetes mellitus, female gender, and lower LVEF.

Figure 1.

Total cohort by WCD group. N=4958. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red = No WCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards analyses in All Patients and CABG and PCI subgroups.

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ALL PATIENTS | |||

| WCD use | 0.614 | 0.486-0.776 | <0.0001 |

| Age, year | 1.033 | 1.028-1.038 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.130 | 0.983-1.298 | 0.085 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.427 | 1.285-1.585 | <0.0001 |

| Female gender | 1.168 | 1.043-1.309 | 0.0073 |

| LVEF,% | 0.974 | 0.967-0.981 | <0.0001 |

| POST-CABG | |||

| WCD use | 0.619 | 0.385-0.997 | 0.048 |

| Age, year | 1.029 | 1.021-1.037 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.085 | 0.886-1.328 | 0.43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.264 | 1.080-1.480 | 0.0035 |

| Female gender | 1.287 | 1.081-1.533 | 0.0046 |

| LVEF,% | 0.982 | 0.971-0.993 | 0.0011 |

| POST-PCI | |||

| WCD use | 0.430 | 0.290-0.638 | <0.0001 |

| Age, year | 1.036 | 1.029-1.042 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.163 | 0.961-1.409 | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.556 | 1.351-1.793 | <0.0001 |

| Female gender | 1.059 | 0.910-1.234 | 0.46 |

| LVEF,% | 0.960 | 0.950-0.969 | <0.0001 |

Survival curves indicated higher early compared to later risk in the No WCD group that was not evident in the WCD group, a finding confirmed in hazard function (instantaneous risk of death) curves stratified by WCD (Figure 1A inset). Survival analysis of the first 90 days showed better survival in the WCD group compared to the No WCD group (HR 0.54, 95%CI 0.43-0.68, p<0.0001). Mortality at 90 days was 2% in the WCD and 7% in the No WCD group. Further analysis restricted to survival outcomes after the first three months showed a continued survival advantage in the WCD group (HR 0.74, 95%CI 0.57-0.97, p=0.027).

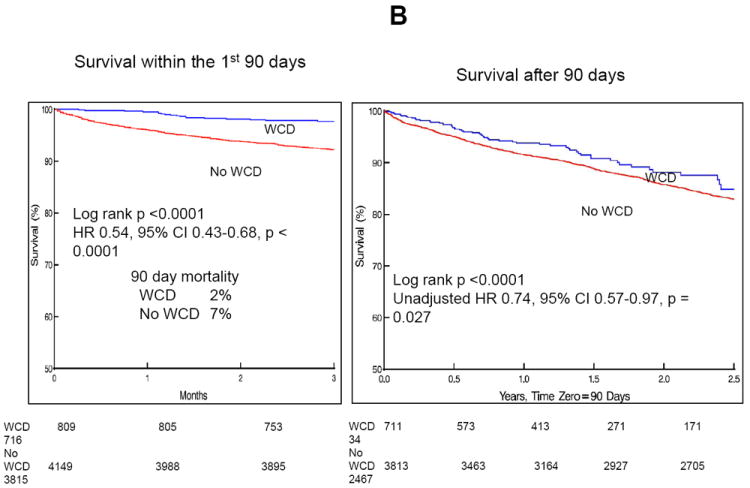

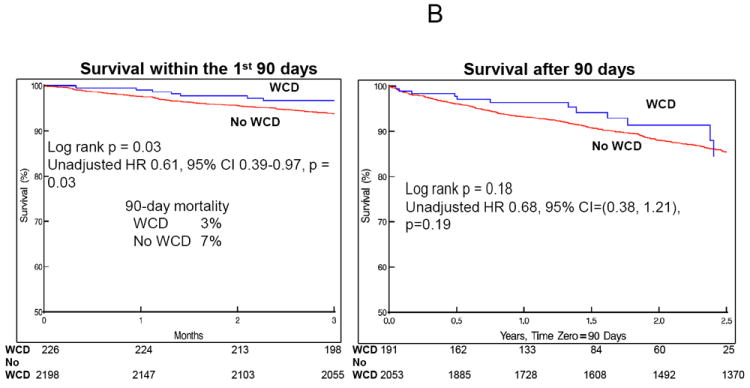

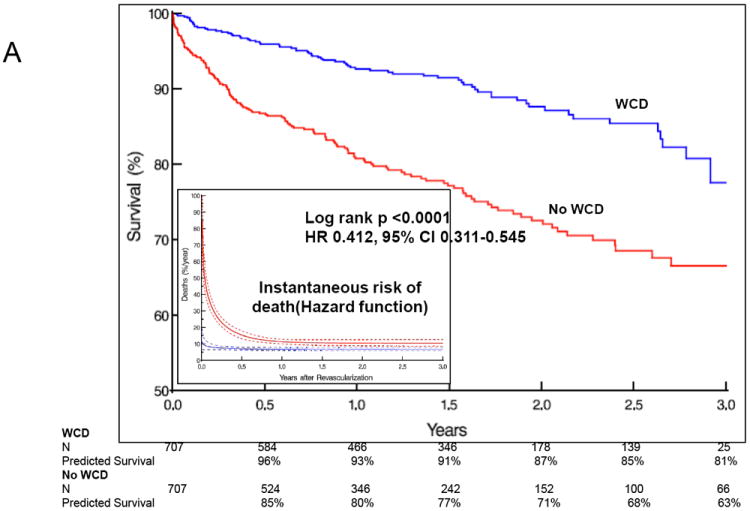

CABG Cohort

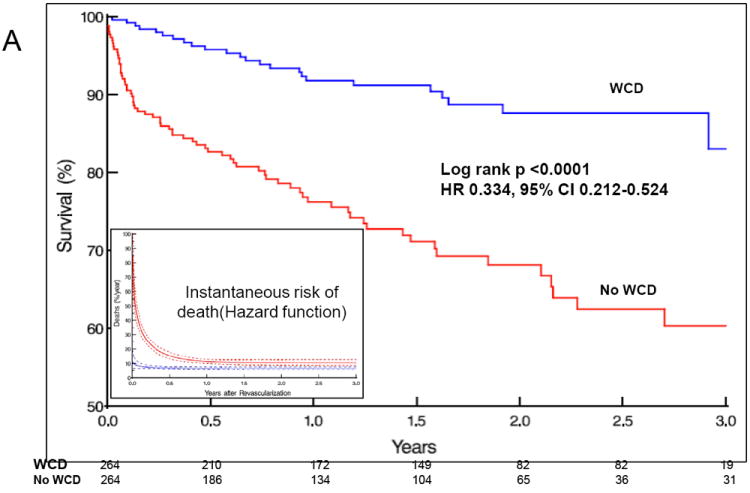

In the CABG cohort (follow-up 3.2±2.5 years, median 2.9 years), Kaplan-Meier survival analyses stratified by WCD use (Figure 2A) showed significantly better survival in the WCD compared to the No WCD group with univariate HR 0.596, 95%CI 0.372-0.957, p=0.03. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses (Table 2), demonstrated that WCD use was associated with a 38% lower risk of death (HR 0.619, 95%CI 0.385-0.997, adjusted p=0.048). Other predictors of long term mortality included older age, diabetes mellitus, female gender, and lower LVEF.

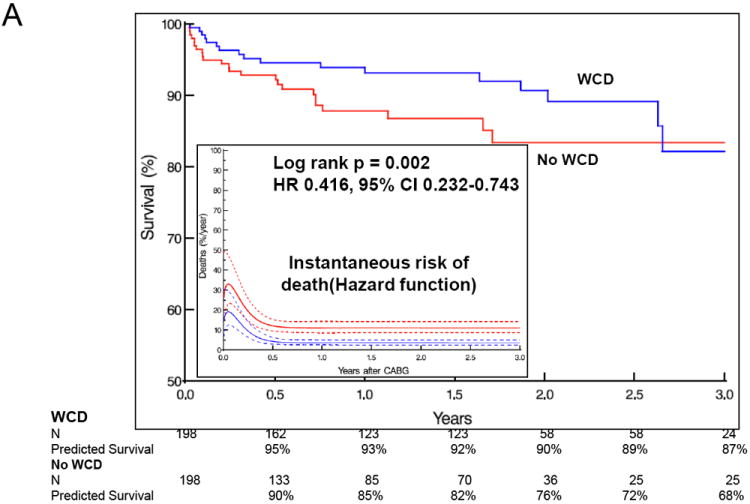

Figure 2.

CABG cohort by WCD group. N=2,424. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red=NoWCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Hazard function curves in the CABG cohort stratified by WCD (Figure 2A inset) demonstrated higher risk of death in the early phase of the study for both WCD and No WCD groups, although the early risk appeared higher in the No WCD group. Survival analysis restricted to the first 90 days after CABG (Figure 2B left) showed better survival in the WCD group compared to the No WCD group (HR 0.61, 95%CI 0.39-0.97, p=0.03). Mortality in the WCD vs. No WCD cohorts was 1% vs. 3% at 1 month, 3% vs. 7% at 3 months, 5% vs. 9% at 6 months, and 7% vs. 12% at 1 year, respectively. Analysis of survival after the first 90 days (Figure 2B right) showed no significant difference between WCD and No WCD groups (HR 0.68, 95%CI 0.38-1.21, p=0.19), suggesting the observed mortality difference was accrued within the first 90 days.

PCI Cohort

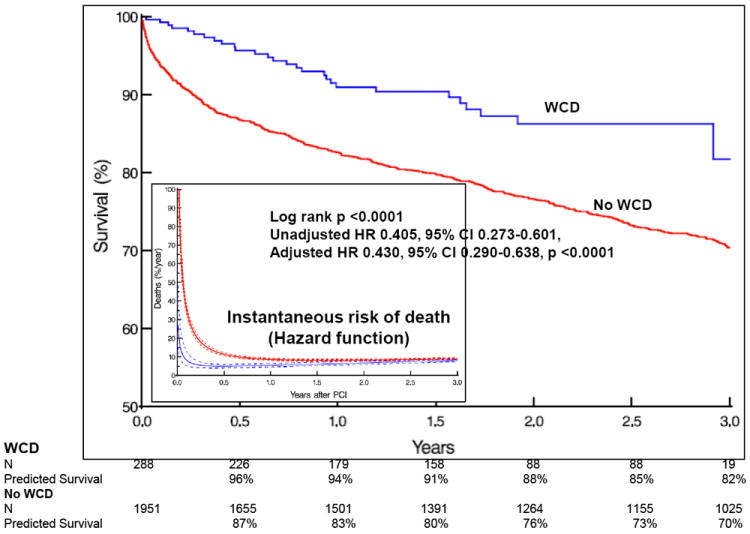

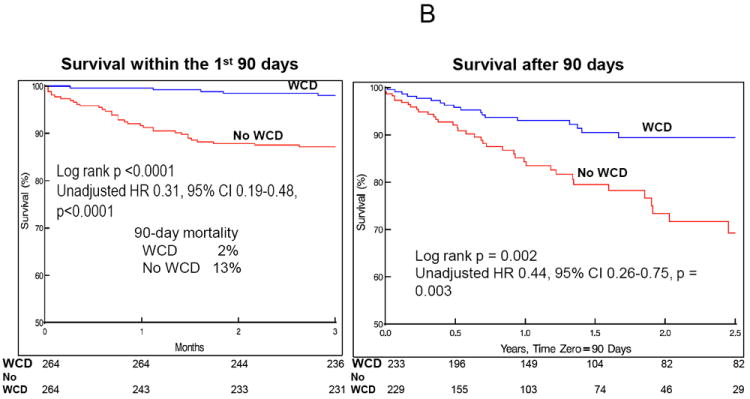

In the PCI cohort (follow-up 3.1±2.3 years, median 2.8 years), Kaplan-Meier survival analyses stratified by WCD use (Figure 3A) demonstrated better survival in the WCD compared to the No WCD group with univariate HR 0.405, 95%CI 0.273-0.601, p<0.0001. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses (Table 2) showed that after PCI WCD use was associated with a 57% lower risk of death (HR 0.430, 95%CI 0.290-0.638, p<0.0001). Other predictors of long term mortality included age, diabetes mellitus, and lower LVEF.

Figure 3.

PCI cohort by WCD group. N=2,239. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red = No WCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Hazard function analysis stratified by WCD (Figure 3A inset) demonstrated higher risk of death in the early phase after PCI in both WCD and No WCD users, but early risk appeared less marked in the WCD group. Survival analysis restricted to the first 90 days after PCI (Figure 3B left) showed significantly better survival in the WCD compared to the No WCD group (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.31-0.66, p<0.0001). Mortality in the WCD vs. No WCD PCI cohorts was 1% vs. 6% at 1 month, 2% vs. 10% at 3 months, 4% vs. 13% at 6 months, and 6% vs. 17% at 1 year, respectively. Analysis of survival after 90 days showed a persistent significant difference between the two groups (HR 0.66, 95%CI 0.44-0.99, p=0.043), suggesting that observed mortality differences continued to accrue beyond the first 90 days (Figure 3B right).

Propensity score matched groups from the total cohort

The C-statistic of the saturated propensity model for combined PCI and CABG cohorts was 0.89. Greedy matching using propensity scores yielded 707 (87% of WCD patients) well matched pairs (Supplemental Figure 1). Propensity matched groups showed no significant patient characteristic differences between WCD and No WCD groups after matching, except for younger age in the WCD group (Supplemental Table 3).

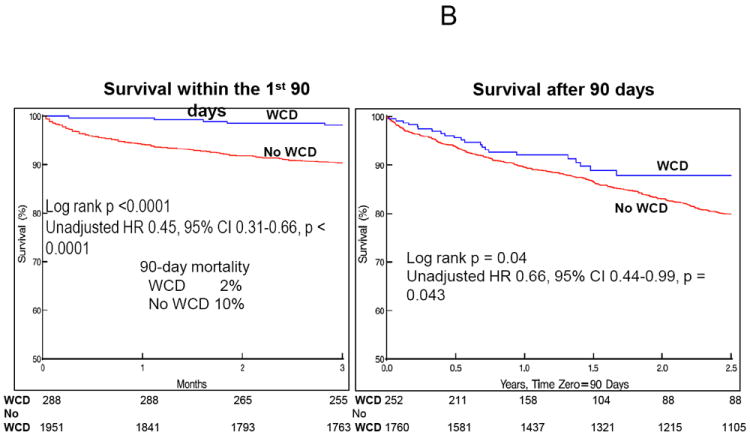

Between matched groups from the total cohort (Figure 4A), there remained a significant difference in survival with better survival in the WCD group (HR 0.412, 95%CI 0.311-0.545, p<0.0001). Hazard function curves (Figure 4A inset) again showed higher early risk of death in the No WCDgroup that was much less marked in the WCD group. Survival analysis of the first 90 days after revascularization (Figure 4B left) showed better survival in the WCD group compared to the No WCD group (HR 0.41, 95%CI 0.31-0.55, p<0.0001). Survival analyses after 90 days (Figure 4B right) showed continued survival differences with better survival in the WCD group (HR 0.52, 95%CI 0.37-0.72, p=0.0001), suggesting continued survival differences extending beyond the first three months.

Figure 4.

Propensity score matched groups from the total cohort by WCD group. N=707, each group. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red = No WCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

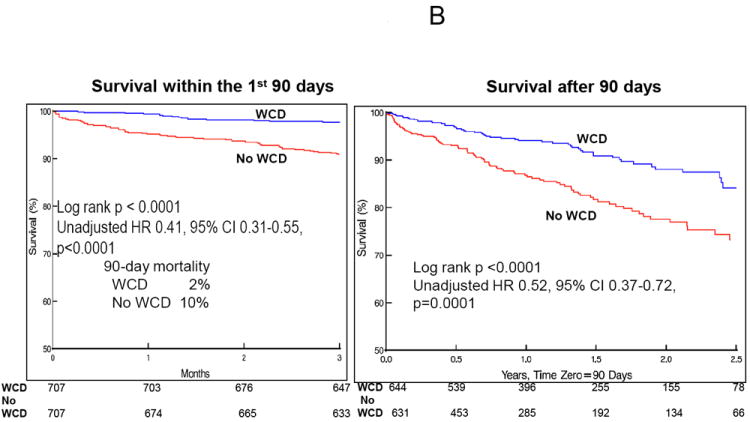

Propensity score matched CABG cohort

The C-statistic of the saturated propensity model for CABG was 0.89. Greedy matching using propensity scores yielded 198 (88% of CABG WCD patients) well matched pairs (Supplemental Figure 2) with no significant differences in patient characteristics between WCD and No WCD groups after propensity matching (Supplemental Table 3).

Between the matched CABG cohorts (Figure 5A), a significant difference in survival remained with better survival in the WCD group (HR 0.416, 95%CI 0.232-0.743, p=0.002). Survival analysis of the first 90 days after CABG in the matched groups (Figure 5B left) showed better survival in the WCD compared to the No WCD group (p=0.002), but on univariate Cox proportional hazards modeling, differences were not significant (HR 0.59, 95%CI 0.32-1.103, p=0.42). Analyses after the first 90 days (Figure 5B right) also showed no significant differences between WCD and No WCD groups (HR 0.65, 95%CI 0.28-1.48, p=0.3). Thus in this analysis, WCD use was associated with significantly better overall long term survival, but early and late mortality differences were not demonstrated.

Figure 5.

Propensity score matched groups from the CABG cohort by WCD group. N=198, each group. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red = No WCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Propensity score matched PCI cohort

The C-statistic of the saturated propensity model for PCI was 0.87. Greedy matching using propensity scores yielded 264 (92% of PCI WCD patients) well-matched pairs with no significant differences in patient characteristics between WCD and No WCD groups after matching (Supplemental Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 3).

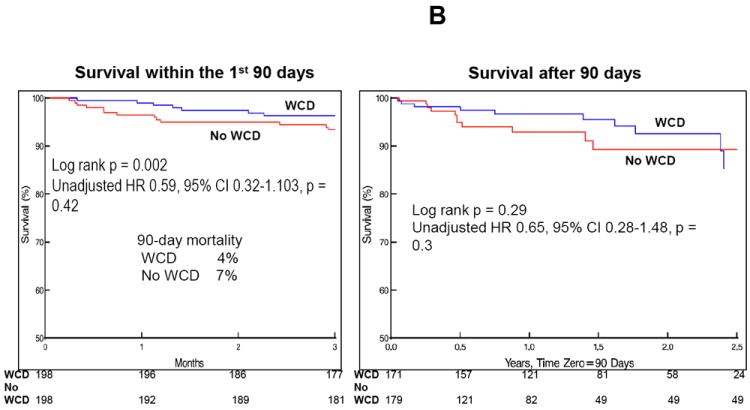

Between the matched PCI cohorts (Figure 6A) a significant difference in survival was evident with better survival in the WCD group (HR 0.334, 95%CI 0.212-0.524, p<0.0001). Survival analysis of the first 90 days after PCI showed significantly better survival in the WCD compared to the No WCD group (HR 0.31, 95%CI 0.19-0.48, p<0.0001). Survival analysis after 90 days showed a persistent significant difference between groups (HR 0.44, 95%CI 0.26-0.75, p=0.003), suggesting continued survival differences beyond the first three months.

Figure 6.

Propensity score matched groups from the PCI cohort by WCD group. N=264, each group. A. Long-term Kaplan-Meier survival. Inset: Hazard function curves - instantaneous risk of death (hazard function) stratified by WCD use. Solid lines are parametric hazard estimates enclosed within dashed 68% confidence bands equivalent to 1 standard deviation. B. Survival in the first 90 days (left) and after 90 days (right). Blue = WCD patients. Red = No WCD patients. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Arrhythmia events during WCD use and subsequent ICD implantation

Over the entire period of WCD use 18 appropriate defibrillations occurred in 11 patients (1.3% of the WCD group) for VT/VF. Defibrillations were successful in 12/18 shocks. One patient required 8 shocks for 2 separate VT episodes. Inappropriate shocks numbered 13 (42% of total therapies), 3 for atrial fibrillation/flutter, one for sinus tachycardia at 180 bpm and 9 for sensing channel noise. Of 3 asystolic events, 2 were fatal. The surviving patient had a transient self-terminating 10-second episode. The first patient who died had VT at 150-170 bpm, under the VT detection criterion programmed at 180 bpm, which degenerated into slow VF, still under the rate criterion, with eventual asystole. The second patient who died had an idioventricular rhythm at 55 bpm that gradually slowed to asystole; he was found dead wearing the WCD.

In the WCD database, 32% of the CABG cohort and 30% of the PCI cohort subsequently underwent ICD implantation. These data were not available for the No WCD group.

Early hazard in propensity score matched groups

Early period hazard function curves demonstrating instantaneous risk of death for the two pairs of matched CABG and PCI cohorts are shown in Supplemental Figure 4 for the first year and first 3 months after revascularization. Curves demonstrate that the early risk appears most marked within the first 3 months with lower early phase risk in the WCD groups.

Discussion

This study of survival after CABG and PCI demonstrated significant risk of death early after coronary revascularization procedures in patients with LV dysfunction, consistent with prior studies16 that suggested higher mortality risks early after cardiac events. This period likely carries risk of arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic death. Thus, a critical question is whether arrhythmic protection might improve early survival in high risk groups. Early ICD implantation after MI for primary prevention of SCD has failed to show significant survival benefits;4, 5 reductions in arrhythmic death were counterbalanced by non-arrhythmic mortality. Analogous situations may pertain to post-revascularization periods. We sought to determine if a non-invasive method of arrhythmia protection might yield demonstrable survival benefits in this early period, as such a method might minimize device-related non-arrhythmic complications.

In both unmatched and propensity score matched total, CABG, and PCI cohorts, findings were remarkably consistent with significantly better survival in WCD users. Although the study was a comparison of data from a single high-volume, high patient acuity center to national registry WCD data, we attempted to adjust for potential confounders using multivariable Cox proportional hazards modeling and propensity score matched populations. Consistent significant differences in survival between WCD and non-WCD users remained demonstrable. Due to limitations in available patient characteristics in the national database, these methods could not fully account for all comorbid factors. However, although the WCD group was younger, this group had significantly lower LVEF than the No WCD group, and the propensity-matched CABG and PCI analyses were well balanced in all covariates used in matching, including age and LVEF.

Despite these limitations, a major outcome of this study should be a highlighting of the high early mortality hazard after coronary revascularization in patients with LVEF≤35% who do not have an ICD (or WCD). Review of survival curves from prior studies of patients with risk markers, such as ventricular dysfunction, after CABG and PCI confirm similar higher early mortality as observed in our cohorts.17-20 Moreover, in two recent large national databases of survival after CABG and PCI, similar early mortality hazards were evident in patients with reduced LV function. In 348,341 isolated CABG patients ≥65 years old from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database linked to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) databases, mortality was 7.6% at 30 days and 18.5% at 1 year after CABG in patients with LVEF<30% and 4.4% and 11.6% in patients with LVEF 30-45%, respectively.21 Survival curves from this study showed early mortality hazard similar to the current study (Supplemental Figure 5). We report here comparable, if not better, 3% 1-month and 12% 1-year mortality in our No WCD CABG cohort, despite inclusion of concomitant procedures and mean LVEF of 23.2%. A recent large analysis of mortality after PCI in 343,466 patients from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) linked to CMS databases reported 3% overall mortality at 30 days and 6% at 6 months. Survival curves also demonstrated early mortality hazard, similar to our current study, that was most marked in patients with LVEF<30%, where mortality appeared comparable to or exceeded the early mortality reported in our No WCD cohort with mean LVEF of 27.3% and in the WCD cohort with mean LVEF of 26.3% (Supplemental Figure 6).22

The differences in early mortality hazard and long term survival with early WCD use were most marked after PCI and less marked after CABG. Thus, early benefits of WCD use after revascularization may be potentially highest after PCI. The PCI cohort contained a proportion of patients that had recent MI. Whether the defibrillation testing typically performed with ICD implants, inflammatory reactions or infectious complications associated with ICDs contribute to non-arrhythmic deaths or overall mortality early after MI or revascularization is unknown, but these would theoretically be avoided using a noninvasive bridging strategy.

Arrhythmic event analyses demonstrated the observed mortality differences were not entirely due to defibrillation from the WCD, as only 1.3% of the WCD group were documented to have received appropriate defibrillation therapy during the period of WCD use. Inappropriate WCD therapies represented 41% of total therapies, but incidence remained low (1.6%/patient, or 0.6%/month).

The low incidence of asystole (0.4%) but high associated mortality was comparable to that previously reported in WCD users.10

Mean WCD use was under 90 days, yet in total and PCI unmatched and matched cohorts, continued survival advantages appeared beyond 90 days, again suggesting that additional factors beyond actual WCD use may be important. WCD users may be more likely to maintain medical contact and follow-up, including earlier follow-up for symptoms short of arrhythmic events triggering shocks, and/or more consistent reassessment of their LVEF for subsequent ICD decisions after the 3-month period. The more marked long term differences in survival benefit seen in the PCI cohorts compared to the CABG cohorts may be related to closer follow-up after CABG compared to the less invasive PCI procedures.

The early risk period with high mortality during the first three months after revascularization in patients with LVEF≤35% indicates a need for further studies to assess methods to improve survival outcomes in this high risk group after CABG or PCI. At minimum, concerted efforts to assure follow-up and assessment for long-term SCD risk and ICD implantation for continued low LVEF after 3 months appear well indicated.

Limitations

The national WCD database was limited in the variables collected, including concomitant surgeries and other potential confounding variables,17-19, 23 and revascularization mode was missing from 288 subjects, excluding these subjects from the propensity-matched analyses. The Cleveland Clinic No WCD group also lacked specific post-discharge tracking of ICD implantation, and we had no hospital length of stay data for the WCD group. The study is retrospective and despite use of multivariable Cox regression and propensity score matched analyses, which have been shown to reduce potential bias and confounding in epidemiological association studies,14, 24, 25 unmeasured confounding variables could have accounted for observed differences. The Cox proportional hazards model was also limited by non-proportional hazards. Therefore, instantaneous hazard functions were calculated and presented. The comparison No WCD group was derived from a high volume center that performs complex procedures in patients with multiple comorbidites and high acuity and might have biased toward better survival in a national WCD registry. Nevertheless, using two methods of analysis, consistent differences in survival were observed. Moreover, large national databases of PCI or CABG in patients with LV dysfunction show similar, and perhaps even worse, early hazard and overall mortality compared to our No WCD cohorts (Supplemental Figures 5,6).21, 22 The findings of this study should be limited to hypothesis generation without attribution of causality to survival differences associated with WCD use, but rationalize further studies to evaluate the efficacy of the WCD and other therapies on reducing early and late phase mortality in post-revascularization patients with reduced LV function.

Conclusions

Patients with LVEF≤35% have higher early compared to late mortality after coronary revascularization, particularly after PCI. Early hazard appeared less marked in WCD users, although differences in mortality were not attributable solely to therapies for ventricular arrhythmia. This study highlights the need for targeting measures to reduce early mortality in the first 3 months after coronary revascularization, including PCI, and the need for further studies to ascertain if WCD use as a bridge to LVEF improvement or ICD implantation can improve survival outcomes after coronary revascularization. Until prospective randomized data becomes available, it is our opinion that it remains reasonable to risk stratify and identify highest risk groups so that there can be consideration of rational prescription of the WCD as a bridge to LV improvement or ICD implantation, or at least planning for closer follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular dysfunction with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, but ICD implantation is typically deferred for 3 months after coronary revascularization procedures, as ICD trials typically excluded this time period from study. This study shows that patients with LVEF ≤35% are at particularly high risk for mortality early after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), a finding that was most marked after PCI. In contrast, this high early mortality was not observed in survival curves from a national database of patients with LV dysfunction, although this apparent difference cannot be wholly attributed to successful appropriate therapy for ventricular arrhythmias. In this non-randomized comparison, wearable cardioverter defibrillator (WCD) use may have been associated with other confounding factors, including potential triggering of closer follow-up and reassessment for ICD implantation at subsequent follow-up. These findings emphasize the need to address the early mortality risk after coronary revascularization. Although results suggest consideration for use of a WCD in particularly high risk patients during the period of recovery after PCI or CABG prior to reassessment of LV function and indications for ICD implantation, whether WCD use would result in mortality reduction during this early period should be tested in a randomized clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: ZOLL provided WCD data, but no study funding. Study was designed at Cleveland Clinic and statistical analysis performed independently by Cleveland Clinic statisticians. All members of the Cleveland Clinic Section of Cardiac Electrophysiology and Pacing (EMC, PJT, MKC) participate in industry-funded research with Boston Scientific, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and Biotronik. EER =consults for Medtronic. AMG performs research with St. Jude Medical. JAG and SJS are employees of ZOLL. MKC performs research funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL090620), and ZOLL ($0), and has been a speaker ($0 compensation) for Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, and ZOLL.

References

- 1.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Klein H, Levine JH, Saksena S, Waldo AL, Wilber D, Brown MW, Heo M. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Dorian P, Roberts RS, Hampton JR, Hatala R, Fain E, Gent M, Connolly SJ. Prophylactic use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2481–2488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbeck G, Andresen D, Seidl K, Brachmann J, Hoffmann E, Wojciechowski D, Kornacewicz-Jach Z, Sredniawa B, Lupkovics G, Hofgartner F, Lubinski A, Rosenqvist M, Habets A, Wegscheider K, Senges J. Defibrillator implantation early after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1427–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilber DJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, Lin AC, Andrews ML, Burke M, Moss AJ. Time dependence of mortality risk and defibrillator benefit after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:1082–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121328.12536.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon SD, Zelenkofske S, McMurray JJ, Finn PV, Velazquez E, Ertl G, Harsanyi A, Rouleau JL, Maggioni A, Kober L, White H, Van de Werf F, Pieper K, Califf RM, Pfeffer MA. Sudden death in patients with myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or both. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2581–2588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigger JT., Jr Prophylactic use of implanted cardiac defibrillators in patients at high risk for ventricular arrhythmias after coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. Coronary artery bypass graft (cabg) patch trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1569–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman AM, Klein H, Tchou P, Murali S, Hall WJ, Mancini D, Boehmer J, Harvey M, Heilman MS, Szymkiewicz SJ, Moss AJ. Use of a wearable defibrillator in terminating tachyarrhythmias in patients at high risk for sudden death: Results of the wearit/biroad. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung MK, Szymkiewicz SJ, Shao M, Zishiri E, Niebauer MJ, Lindsay BD, Tchou PJ. Aggregate national experience with the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator: Event rates, compliance, and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee BK, Olgin JE. Role of wearable and automatic external defibrillators in improving survival in patients at risk for sudden cardiac death. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2009;11:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s11936-009-0036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackstone EH, Naftel DC, Turner ME. The decomposition of time-varying hazard into phases, each incorporating a separate stream of concomitant information. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:615–624. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackstone EH. Comparing apples and oranges. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:8–15. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.120329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergstralh EJ, Konsanke JL. Computerized matching of cases to controls. Technical Report #56, Mayo Foundation. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Sudden cardiac death. Structure, function, and time-dependence of risk. Circulation. 1992;85:I2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alderman EL, Fisher LD, Litwin P, Kaiser GC, Myers WO, Maynard C, Levine F, Schloss M. Results of coronary artery surgery in patients with poor left ventricular function (cass) Circulation. 1983;68:785–795. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brener SJ, Lytle BW, Casserly IP, Schneider JP, Topol EJ, Lauer MS. Propensity analysis of long-term survival after surgical or percutaneous revascularization in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease and high-risk features. Circulation. 2004;109:2290–2295. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126826.58526.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillis GS, Zehr KJ, Williams AW, Schaff HV, Orzulak TA, Daly RC, Mullany CJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Oh JK. Outcome of patients with low ejection fraction undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: Renal function and mortality after 3.8 years. Circulation. 2006;114:I414–419. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hlatky MA, Boothroyd DB, Bravata DM, Boersma E, Booth J, Brooks MM, Carrie D, Clayton TC, Danchin N, Flather M, Hamm CW, Hueb WA, Kahler J, Kelsey SF, King SB, Kosinski AS, Lopes N, McDonald KM, Rodriguez A, Serruys P, Sigwart U, Stables RH, Owens DK, Pocock SJ. Coronary artery bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary interventions for multivessel disease: A collaborative analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1190–1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Sheng S, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Jacobs JP, Weiss JM, Delong ER, Peterson ED, Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Klein LW, Shaw RE, Garratt K, Moussa I, Shewan CM, Dangas GD, Edwards FH. Predictors of long-term survival following coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: Results from the society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery database (the ascert study) Circulation. 2012;125:1491–1500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Weiss JM, Delong ER, Peterson ED, O’Brien SM, Kolm P, Klein LW, Shaw RE, McKay C, Ritzenthaler LL, Popma JJ, Messenger J, Shahian DM, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Garratt K, Moussa I, Edwards FH, Dangas GD. Prediction of long term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention in older adults: Results from the national cardiovascular data registry. Circulation. 2012;125:1501–1510. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Topkara VK, Cheema FH, Kesavaramanujam S, Mercando ML, Cheema AF, Namerow PB, Argenziano M, Naka Y, Oz MC, Esrig BC. Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with low ejection fraction. Circulation. 2005;112:I344–350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Combining propensity score matching with additional adjustments for prognostic covariates. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:573–585. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.