Abstract

Background

Alcohol abuse and/or dependence (Alcohol Use Disorders, AUDs) and problem and/or pathological gambling (PPG) frequently co-occur with each other and other psychiatric disorders. However, prior studies have not investigated the relative influence of AUD on the associations between PPG and other psychiatric disorders.

Objectives

To use nationally representative data (the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, NESARC, n = 43,093 U.S. Residents ages 18 years and older) to examine the influence of DSM-IV AUD on the associations between gambling and other psychiatric disorders and behaviors.

Main Outcome Measures

Co-occurrence of past-year AUD and Axis I and II disorders and severity of gambling based on the ten inclusionary diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling.

Results

Among non-AUD respondents, increasing gambling severity was associated with increasingly elevated odds for the majority of Axis I and II disorders. Among AUD respondents, this pattern was typically not observed. Alcohol-by-gambling-group interactions for PPG were also found and the odds of these disorders was significantly increased in non-AUD respondents with PPG, but either unchanged or significantly lower in AUD respondents with PPG.

Conclusions

Gambling-related associations exist with multiple psychiatric disorders, but particularly in those without AUD. These associations have important implications with respect to conceptualization, prevention and treatment of psychiatric disorders in individuals with gambling and/or alcohol use disorders.

Keywords: gambling, co-occurring disorders, alcohol dependence, impulse control disorders, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Problem and pathological gambling (PPG) is estimated to cost the US $5 billion annually1. PPG is associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts2, 3, and the association appears influenced by co-occurring psychiatric disorders4. PPG co-occurs with multiple Axis I and II psychiatric disorders5–9 both in community as well as treatment samples10. However, rates of PPG in the community have been estimated at about 5% or less11. Therefore, the majority of people who gamble do so with either no, or few, related problems.

Recreational gambling and sub-syndromal PPG have been associated with multiple functional and clinical measures including physical illness, depression, substance abuse/dependence, alcohol abuse/dependence, bankruptcy and incarceration. Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) have indicated that gamblers, particularly women, with some gambling-related problems, but who do not meet criteria for PPG, are at increased odds of a wide variety of Axis I and Axis II co-occurring disorders10, 12–17 As a majority of adults gamble at a recreational or non-problematic level, an improved understanding of the relationship between subsyndromal as well as syndromal levels of gambling behaviors is of public health importance15, 16, 18, 19.

Although multiple studies have linked PPG and AUD, few have investigated their relative associations with other psychiatric disorders or considered their relative contributions or interactions. Given that PPG and to a lesser extent subsyndromal gambling behaviors are associated with a broad array of psychiatric disorders, investigating the relative contributions of gambling to the risk for other psychopathology among individuals with psychiatric disorders is important for theoretical, societal and clinical purposes.

The current study utilizes data from a community sample of adults to investigate whether the associations between gambling severity, as measured on a dimensional scale, and both Axis I and Axis II psychopathology differ significantly between those who do, and do not, meet criteria for AUD. Findings from such an investigation have implications for characterizing the relative contributions of alcohol use and gambling behaviors and disorders to other psychiatric disorders. Given the high rates of co-occurrence of alcohol use and gambling disorders with other mental health conditions in both community and clinical samples, results could provide important information for targeting and honing prevention and treatment strategies.

Given previous research, we hypothesized that greater gambling severity would be associated with increased odds of multiple psychiatric disorders in both AUD and non-AUD populations. Additionally, we hypothesized that the association between gambling and other psychiatric disorders would be significantly stronger in AUD compared to non-AUD populations.

METHODS

SAMPLE

Data from the 2001–2002 NESARC, described elsewhere8, 20, were analyzed. The NESARC, conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the Bureau of the Census, surveyed a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized U.S. residents (citizens and non-citizens) aged 18 years and over. Respondents were identified using a multi-stage cluster sampling technique, and the sample was enhanced with members of group-living environments, such as dormitories, group homes, shelters, and facilities for housing workers. Jails, prisons, and hospitals were not included. The study over-sampled black and Hispanic households, as well as young adults aged 18 to 24 years. Weights have been calculated to adjust standard errors for these over-samples, the cluster sampling technique, and non-response20. The final sample consisted of 43,093 respondents, representing an 81% response rate. All respondents gave consent to participate, and the current investigation utilizes the publicly-accessible, de-identified data set, and is thus exempt from institutional review board approval.

MEASURES

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM IV version (AUDADIS-IV)21, a structured diagnostic assessment tool, was administered by trained lay interviewers in the NESARC study. The instrument was tested for reliability and validity and found to be a good measure for detecting psychiatric disorders in a community sample20. The publicly-accessible NESARC data set contains diagnostic variables derived from AUDADIS-IV algorithms and based on DSM-IV criteria22. The data contain diagnostic variables for major depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, panic disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, drug dependence, nicotine dependence and pathological gambling, as well as avoidant, dependent, antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and histrionic personality disorders20. The instrument provides the ability to distinguish past-year and lifetime diagnoses. For example, the diagnosis for pathological gambling was determined through this structured clinical instrument that assessed each of the ten symptoms of pathological gambling and then determined whether these symptoms occurred together within the previous twelve months, or prior to the previous year. It also includes exclusions for medical illnesses and substance-induced symptoms. As reported previously, we utilized past year diagnoses with illness and substance exclusions, thus making the diagnoses `primary' or independent as defined by the DSM12, 15.

The primary independent variable of interest was based on ten diagnostic inclusionary criteria for pathological gambling, five of which are required for a DSM-IV diagnosis of pathological gambling22. As previous data suggest that gambling severity as defined by DSM-IV criteria lies along a spectrum6, 9, 23, we divided the sample into four groups: non- and low-frequency gamblers (reporting fewer than five episodes of gambling in a single year in their lifetime); low-risk gamblers (reporting more than five episodes of gambling in a single year and no symptoms of pathological gambling in the past year); at risk gamblers (reporting one or two symptoms of pathological gambling in the previous year); and problem/pathological gamblers (PPG, reporting three or more symptoms of pathological gambling in the previous year. We have utilized this grouping in other analyses of gambling data10, 12, 15. The low frequency of pathological gambling (less than 1% of the sample reported ≥5 symptoms) necessitated the combination of the problem and pathological groups, a strategy employed in prior gambling studies6, 18.

Alcohol dependence was defined as one or more symptoms of at least three of the following criteria occurring within the previous 12 months: (1) tolerance, (2) withdrawal (2 + symptoms or drinking to relieve or avoid withdrawal), (3) persistent desire or attempts to reduce or stop drinking, (4) much time spent drinking or recovering from drinking, (5) reduction/cessation of important activities in favor of drinking, (6) impaired control over drinking and (7) continued use despite physical or psychological problems caused by drinking. Alcohol abuse was defined as the occurrence of at least one symptom of any of the four abuse criteria: (1) continued use despite interpersonal problems caused by drinking, (2) recurrent hazardous use, (3) recurrent alcohol-related legal problems and (4) inability to fulfill major role obligations because of drinking. For the purposes of these analyses, alcohol abuse and dependence groups were combined so that individuals in this group could have abuse and/or dependence. Other variables utilized in the analysis include self-reported gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, current employment, marital status and income.

DATA ANALYSIS

In a manner similar to previous NESARC analyses8, we first examined the associations between gambling and demographic characteristics and four alcohol use groups: those with abuse plus dependence, those with dependence alone, those with abuse alone, and those with neither abuse nor dependence. We did this by fitting a multinomial logistic regression with the four alcohol use groups as the dependent variable. Subsequent to this analysis, we combined the three alcohol use groups into AUD versus non-AUD, to simplify presentation of results and to preserve the statistical power to examine comorbidity with other disorders.

We next examined the association between gender, gambling and other socio-demographic variables stratified by AUD in order to identify potential confounders for multivariable models. Subsequently, we calculated unadjusted weighted rates of psychiatric disorders, stratified by both AUD and gambling severity. Finally, we fit a series of logistic regression models where Axis I and II psychiatric disorders were the dependent variables of interest and the four-level gambling variable, AUD and an interaction between AUD and gambling were the independent variables of interest, adjusting for previously identified confounders. We analyzed data using SUDAAN (Research triangle) software and the NESARC-calculated weights to account for sampling design and non-response.

RESULTS

The survey sample consisted of 38796 subjects (90.0%) without and 3231 subjects (7.5%) with AUD. 1066 subjects provided inadequate information for diagnostic categorization. Chi-square analyses identified a number of sociodemographic variables that varied by gambling severity when stratified by individuals with and without AUD. Amongst individuals without AUD, associations with gambling severity were significant at p<0.05 for all sociodemographic variables (Table 1). Among individuals with AUD, differences were noted across gambling severity in gender, ethnicity, education and marital status but not employment or annual household income. Due to the strong associations of these variables to gambling severity, all demographic variables were included in future multivariable models.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the NESARC sample, by alcohol abuse/dependence and severity of gambling problem

| No alcohol abuse/dependence (N=38,796) | Alcohol abuse/dependence (N=3231)* | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-gamblers (N=28,991) |

Low-risk gamblers (N=8,894) |

At-risk Gamblers (N=748) |

Problem/pathological qamblers (N=163) |

Non-gamblers (N=1,894) |

Low-risk gamblers (N=1,070) |

At-risk Gamblers (N=197) |

Problem/pathological gamblers (N=70) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | N | % | X2 (df) | p | N | % | N | % | N | % | X2 (df) | p | ||||

| Gender | 111.69 | <0.0001 | 31.18 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 10,847 | 42.1 | 4,543 | 55.6 | 388 | 59.1 | 84 | 59.3 | 1,155 | 64.4 | 788.0 | 76.8 | 148 | 76.5 | 49 | 77.5 | ||||

| Female | 18,144 | 57.9 | 4,351 | 44.4 | 360 | 40.9 | 79 | 40.7 | 739 | 35.6 | 282.0 | 23.2 | 49 | 23.5 | 21 | 22.5 | ||||

| Black race | 5,838 | 11.8 | 1,780 | 11.0 | 181.0 | 13.6 | 59 | 23.7 | 16.83 | 0.0018 | 266 | 9.1 | 160.0 | 8.8 | 40 | 14.0 | 20 | 18.1 | 7.09 | 0.0793 |

| White race | 21,909 | 82.4 | 6,846 | 84.9 | 540.0 | 82.0 | 91 | 63.0 | 34.03 | <0.0001 | 1,562 | 87.6 | 874.0 | 86.8 | 151 | 83.0 | 49 | 76.4 | 4.89 | 0.191 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6,173 | 13.0 | 1,242 | 7.9 | 114.0 | 8.1 | 20 | 6.3 | 28.26 | <0.0001 | 375 | 12.3 | 164.0 | 8.9 | 30 | 7.3 | 11 | 7.5 | 12.14 | 0.01 |

| Education | 47.71 | <0.0001 | 21.56 | 0.0207 | ||||||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 5,640 | 16.5 | 1,361 | 13.5 | 145.0 | 16.3 | 35 | 19.5 | 278 | 14.1 | 116.0 | 9.9 | 36 | 16.2 | 13 | 19.4 | ||||

| HS or GED | 8,287 | 28.7 | 2,707 | 30.9 | 241.0 | 33.2 | 53 | 36.6 | 525 | 27.2 | 332.0 | 30.0 | 55 | 30.4 | 27 | 39.3 | ||||

| Some college | 8,134 | 28.9 | 2,793 | 31.5 | 238.0 | 32.0 | 49 | 27.7 | 643 | 35.7 | 412.0 | 40.5 | 72 | 36.2 | 22 | 28.0 | ||||

| College degree or higher | 6,930 | 25.9 | 2,033 | 24.1 | 124.0 | 18.5 | 26 | 16.2 | 448 | 23.0 | 210.0 | 19.6 | 34 | 17.2 | 8 | 13.3 | ||||

| Marital status | 77.81 | <0.0001 | 25.41 | 0.0012 | ||||||||||||||||

| Married | 15,053 | 62.5 | 4,984 | 67.6 | 353.0 | 58.4 | 71 | 51.8 | 674 | 41.5 | 428.0 | 48.4 | 83 | 46.9 | 21 | 36.5 | ||||

| Previously married | 7,439 | 17.1 | 2,402 | 18.0 | 210.0 | 20.1 | 42 | 20.4 | 392 | 15.8 | 268.0 | 18.7 | 30 | 10.5 | 18 | 18.0 | ||||

| Never married | 6,499 | 20.4 | 1,508 | 14.5 | 185.0 | 21.6 | 50 | 27.8 | 828 | 42.7 | 374.0 | 32.9 | 84 | 42.6 | 31 | 45.5 | ||||

| Employment status | 24.25 | 0.0017 | 7.21 | 0.3166 | ||||||||||||||||

| Full-time | 14,427 | 51.4 | 4,676 | 55.1 | 396.0 | 54.7 | 89 | 53.4 | 1,218 | 63.4 | 712.0 | 66.7 | 133 | 70.8 | 42 | 61.0 | ||||

| Part-time | 2,916 | 10.7 | 784 | 9.3 | 78.0 | 10.0 | 20 | 14.1 | 233 | 12.6 | 114.0 | 12.1 | 15 | 8.8 | 5 | 8.9 | ||||

| Not working | 11,648 | 37.9 | 3,434 | 35.6 | 274.0 | 35.3 | 54 | 32.5 | 443 | 24.0 | 244.0 | 21.1 | 49 | 20.4 | 23 | 30.1 | ||||

| Age in years, Mean and SE | 45.3 | 0.2 | 48.8 | 0.2 | 46.0 | 0.8 | 43.9 | 2.0 | 53.98 | <0.0001 | 33.2 | 0.4 | 37.4 | 0.5 | 34.0 | 1.1 | 34.2 | 1.8 | 16.64 | <0.0001 |

| Annual household income ($), Mean and SE | 52935 | 945 | 56434 | 1119 | 60278 | 4789 | 44989 | 3195 | 5.06 | 0.0103 | 54,441 | 2,221 | 59,314 | 3,976 | 58,044 | 4,512 | 43,982 | 5,381 | 1.23 | 0.2944 |

note: 96 of 3327 individuals indicated in table 1 did not provide sufficient gambling information and were not included in subsequent anaylses.

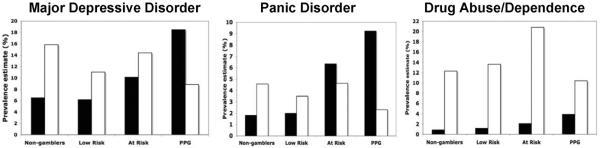

With the hypothesis that gambling severity would be more strongly associated with psychiatric disorders in individuals with AUD compared to those without, we next analyzed unadjusted rates of psychiatric disorders across gambling severity levels, stratified by individuals with and without AUD (Table 2). We note several important patterns. First, there were significant associations between gambling severity and seven (79%) of the Axis I disorders assessed in individuals without AUD; however, such associations were present for only two (22%) of the disorders assessed in those with AUD (Table 2). Second, a similar number of Axis II disorders showed significant associations with gambling severity in individuals with (n=5) and without AUD (n=6). Third, among gamblers the rates of psychiatric disorders followed consistent patterns with respect to gambling severity, with increased rates associated with increasing gambling severity. For example, rates of major depression increased from 6.5% in non-gamblers to 10.1% in at-risk gamblers to 18.5% in problem-pathological gamblers (Table 2, Figure 1). However, rates of some disorders were higher in non-gamblers than in low-risk gamblers, especially in the group with AUD. Among people with AUD, rates of major depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, panic disorder, simple phobia, and every personality disorder except antisocial were higher in non-gamblers than in low-risk gamblers.

Table 2.

Prevalence estimates of psychiatric disorders in the NESARC data, by AAD and gambling problem severity

| No alcohol abuse/dependence |

Alcohol abuse/dependence |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Non-gamblers2 | Low-risk gamblers | At-risk gamblers | Problem/pathological gamblers |

X2 | p | Non-gamblers | Low-risk gamblers | At-risk gamblers | Problem/pathological gamblers |

X2 | p |

| Major Depression | 6.52 | 6.17 | 10.12 | 18.48 | 18.18 | 0.0011 | 15.85 | 11.03 | 14.43 | 8.83 | 10.62 | 0.0193 |

| Dysthymia | 1.7 | 1.74 | 2.39 | 6.63 | 5.46 | 0.1521 | 2.95 | 2.52 | 5.06 | 3.96 | 2.19 | 0.5376 |

| Mania | 1.24 | 1.73 | 2.06 | 9.14 | 16.39 | 0.0021 | 4.64 | 4.16 | 8.02 | 7.06 | 3.56 | 0.3223 |

| Hypomania | 0.84 | 1.24 | 2.69 | 1.73 | 11.81 | 0.0121 | 3.8 | 1.78 | 8.05 | 4.28 | 12.7 | 0.0085 |

| Panic Disorder1 | 1.82 | 1.99 | 6.36 | 9.24 | 17.2 | 0.0015 | 4.56 | 3.5 | 4.63 | 2.31 | 3.24 | 0.3639 |

| Social phobia | 2.52 | 2.93 | 3.84 | 10.91 | 9.06 | 0.0359 | 4.04 | 4.29 | 6.91 | 6.62 | 2.83 | 0.4255 |

| Simple phobia | 6.35 | 8.3 | 12.4 | 18.76 | 37.2 | <0.0001 | 10.36 | 9.54 | 14.56 | 27.17 | 6.91 | 0.0853 |

| Generalized anxiety | 1.85 | 2.20 | 1.93 | 9.19 | 6.97 | 0.0832 | 3.29 | 3.89 | 6.18 | 4.21 | 2.58 | 0.467 |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 0.87 | 1.16 | 2.07 | 3.91 | 9.89 | 0.0258 | 12.3 | 13.63 | 20.81 | 10.43 | 5.69 | 0.1391 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Personality Disorders: | ||||||||||||

| Avoidant | 2.2 | 2.03 | 3.15 | 8.75 | 6.43 | 0.1033 | 5.21 | 2.31 | 9.88 | 11.72 | 25.89 | 0.0001 |

| Dependent | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 2.05 | 6.56 | 0.098 | 1.34 | 0.86 | 2.05 | 4.72 | 3.77 | 0.2969 |

| Antisocial | 2.18 | 4.38 | 8.04 | 17.56 | 61.27 | <0.0001 | 11.89 | 11.99 | 18.12 | 27.72 | 8.56 | 0.0439 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 6.75 | 9.57 | 15.1 | 25.72 | 64.22 | <0.0001 | 12.84 | 9.67 | 19.18 | 22.03 | 12.07 | 0.0109 |

| Paranoid | 3.57 | 4.46 | 8.4 | 24.77 | 39.3 | <0.0001 | 10.92 | 7.54 | 15.74 | 28.38 | 18.24 | 0.001 |

| Schizoid | 2.67 | 3.69 | 5.06 | 15.09 | 30.2 | <0.0001 | 5.48 | 3.32 | 8.79 | 17.28 | 14.12 | 0.0049 |

| Histrionic | 1.33 | 1.59 | 3.37 | 8.15 | 14.2 | 0.0048 | 6.2 | 4.79 | 15.57 | 25.09 | 15.11 | 0.0034 |

With or without agoraphobia

Numbers in cells represent prevalence rates of disorders within gambling group

Figure 1.

Gambling severity is associated with increased rates of psychiatric disorders in non-alcohol abusing and/or dependent individuals

Prevalence estimates for psychiatric disorders in the NESARC data. PPG = problem and/or pathological gambling. Black bars = no Alcohol Abuse and/or Dependence, White bars = Alcohol Abuse and/or Dependence

Using non-gamblers as the reference group, we next calculated odds ratios of psychiatric disorders from multivariable models adjusted for age, race, marital status, education, employment and income (Table 3). Results can be divided into findings for those without AUD, findings for those with AUD, and the comparison between those without and with AUD.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios for psychiatric disorders in the NESARC data

| No alcohol abuse/dependence | Alcohol abuse/dependence | Alcohol by gambling interaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Recreational | At risk | PPG | Recreational | At risk | PPG | Recreational | At risk | PPG |

| Major Depression | 1.14 | 1.81† | 3.6† | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.08** | 0.7* | 0.61 | 0.15† |

| Dysthymia | 1.19 | 1.51 | 4.38† | 0.85 | 3.09 | 0.35 | 0.84 | 1.43 | 0.28 |

| Mania | 1.72† | 1.75 | 7.89† | 0.7 | 2.66 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 1.23 | 0.19** |

| Hypomania | 1.87† | 3.45† | 1.88 | 0.17** | 1.66 | 0.68 | 0.3 | 0.69 | 0.60 |

| Panic Disorder | 1.31* | 4.32† | 6.57† | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.04* | 0.7 | 0.29* | 0.08* |

| Social phobia | 1.29* | 1.64* | 5.16† | 1.13 | 2.24 | 0.61 | 0.94 | 1.17 | 0.34 |

| Simple phobia | 1.55† | 2.43† | 3.94† | 0.73 | 1.2 | 3.68 | 0.69* | 0.70 | 0.97 |

| Generalized anxiety | 1.40** | 1.16 | 6.01† | 1.44 | 5.03* | 0.31 | 1.01 | 2.08 | 0.23* |

| Nicotine dep | 1.88† | 2.81† | 5.28† | 0.67 | 1.38 | 1.78 | 0.60† | 0.70 | 0.58 |

| Drug ab/dep | 1.66** | 2.25* | 3.71** | 1.17 | 1.82 | 0.13* | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.19** |

| Personality Disorders: | |||||||||

| Avoidant | 1.08 | 1.52 | 4.26† | 0.25** | 3.51 | 1.32 | 0.48** | 1.52 | 0.56 |

| Dependent | 1.06 | 0.35 | 4.83** | 0.76 | 11.24 | 1.94 | 0.84 | 5.64 | 0.63 |

| Antisocial | 2.14† | 3.55† | 7.99† | 0.53* | 0.65 | --- | 0.5† | 0.43** | -- |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 1.50† | 2.51† | 4.89† | 0.36** | 1.09 | 0.82 | 0.49† | 0.66 | 0.41* |

| Paranoid | 1.54† | 2.60† | 8.68† | 0.41* | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.51† | 0.65 | 0.35* |

| Schizoid | 1.54† | 1.93† | 5.91† | 0.27** | 1.53 | 1.84 | 0.42† | 0.89 | 0.56 |

| Histrionic | 1.43** | 2.62† | 5.91† | 0.56 | 2.27 | 4.2 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.84 |

Odds ratios (OR) are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education,employment, and income

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Among those without AUD, significant associations were noted between gambling severity and nearly all of the Axis I and Axis II disorders. In general, odds ratios indicated increasing odds of disorders as gambling severity increased, compared to non-gamblers. Exceptions to this pattern included major depression, dysthymia, avoidant and dependent personality disorder, where significantly elevated odds were not observed until the at-risk gambling group (for depression) or the problem/pathological gambling group (all others). Significantly elevated rates seen in bivariate analyses of non-gamblers versus low-risk gamblers (Table 2) were not observed here, indicating that these patterns were likely explained by variation in demographic variables used to adjust multivariable models.

Among respondents with AUD, there were few significant associations between gambling severity and Axis I disorders. In addition, in all cases where there were associations, relationships were in the negative direction, indicating lower odds of psychopathology in gamblers than in non-gamblers. Those with PPG and AUD were 92% less likely to have major depression, 96% less likely to have panic disorder, and 87% less likely to have drug abuse/dependence as non-gamblers, while recreational gamblers with AUD were 83% less likely to have hypomania as non-gamblers. For Axis II disorders among those with AUD, significant associations were found exclusively among recreational gamblers compared to non-gamblers. However, a similar pattern was observed, where odds of disorders were significantly lower among gamblers than non-gamblers.

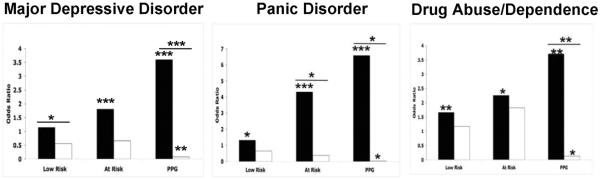

The interaction analyses statistically tested whether associations between gambling and psychopathology were significantly different in those with and without AUD. We found significant interactions for multiple Axis I disorders including major depression, mania, panic disorder, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence and drug abuse/dependence (Table 3, Figure 2). In all cases, interaction terms indicated a lower odds ratio between gambling and the specified disorder in the AUD group as compared to the non-AUD one (Table 3). Similarly, significant gambling-by-alcohol group interactions were noted for all Axis II disorders except dependent and histrionic PD. Again, all significant interaction terms indicated lower odds of disorders in the AUD group as compared to the non-AUD one.

Figure 2.

Gambling Severity is associated with increased odds ratio of psychiatric disorders in non-alcohol abusing and/or dependent individuals

Adjusted odds ratios for psychiatric disorders in the NESARC data. Black bars = no Alcohol Abuse and/or Dependence, White bars = Alcohol Abuse and/or Dependence. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, (—) denotes statistical significance in gambling by alcohol interactions between groups.

DISCUSSION

The present study represents, to our knowledge, the first to investigate in a nationally representative sample the associations between multiple-threshold levels of gambling and Axis I and II psychiatric disorders in individuals with and without AUD. The findings support our a priori hypothesis that greater gambling severity would be associated with multiple psychiatric disorders in non-AUD respondents. In contrast to our hypotheses, however, the odds of a number of disorders in the AUD group were significantly higher in non-gamblers than in gamblers.

Rates of gambling with alcohol abuse/dependence

We found rates of at-risk or problem/pathological gambling of 2.3% among those without AUD and 8.3% among those with AUD. These estimates highlight the important association between alcohol and problem gambling. For example, shared genetic and environmental contributions to the disorders have been reported24, 25, and similar treatment strategies have been found to be effective26, 27. Prior studies indicate strong relationships in community samples with an odds ratio of 3.3 between problem/pathological gambling and AUD in the St. Louis ECA study6 and an odds ratio of 23 between the disorders in a random digit dialing survey28.

Gambling, alcohol and Axis I psychopathology

Our findings of significant associations between gambling behavior and a large number of Axis I disorders in people without AUD supports previous reports of high rates of comorbidity between Axis I disorders and PPG6, 7, 9, 12. We also found high rates of psychopathology among gamblers with AUD. However, while we observed that rates of psychopathology often increased with gambling severity in individuals without AUD, in individuals with AUD non-gamblers often had higher rates of psychopathology than low-risk gamblers. In addition, due to high rates of psychopathology in non-gamblers with AUD, relative odds among gamblers with AUD were significantly reduced or in the opposite direction to our hypotheses. These findings are in part attributable to the comparison groups forming the basis of the odds ratio calculations. That is, relatively low rates of psychopathology were observed in non-gamblers without AUD, rates that would largely reflect the population prevalence of various psychiatric disorders. In this group, increased severity of gambling was typically associated with a broad range of Axis I and II psychopathology, a result consistent with several other studies of gambling and psychopathology. In contrast, rates of psychopathology among non-gamblers with AUD were much higher than rates among non-gamblers without AUD, in part reflecting population-level comorbidity between AUD and a wide range of other disorders. Since this was the comparison group for all gambling groups with AUD, however, relative odds as gambling severity increased were quite variable and reflect a much weaker association between gambling and psychopathology among people with AUD. Thus, the findings do not suggest a synergistic influence between alcohol and gambling severities and co-occurring psychopathology, but rather a more complex relationship.

This is an important finding for several reasons. First, although previous research has demonstrated a high comorbidity between gambling and AUD, no stratification has been done to determine their interaction with other psychiatric disorders in adults. These data are consistent with previous findings in adolescents in which a gambling-by-alcohol interaction was noted in low-frequency drinkers in rates of drug abuse but not in those who drink with moderate to high frequency29. Thus, our data further this observation by extending a possible trend into the adult population, while suggesting that this may also be the case with other Axis I disorders, thus providing a testable hypothesis that other gambling by psychiatric disorder interactions may be found as early as adolescence in individuals with low-frequency drinking patterns.

Second, our findings further refine the relative contribution of alcohol disorders to associations between gambling behavior and psychiatric disorders. As noted above, amongst the strongest relationships between PPG and other psychopathology is that of AUD. However, our data suggest that though these associations occur, as gambling behavior increases in subjects with AUD, psychopathological associations with disorders such as major depression and panic actually decrease. This is an important finding, as it may help to inform and refine our understanding of pathophysiological underpinnings of these disorders, possible common neural substrates, and their treatments.

Third, and related to the second point, strong associations emerged between gambling and Axis I disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), panic disorder (PD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in individuals without AUD. One hypothesis as to why these patterns would not be observed in AUD respondents is that these diagnoses are characterized by a common “internalizing pattern” of behavior, as conceived by Krueger30, where maladjustment is expressed primarily inwardly as anxiety/misery/fear as compared to “externalizing” patterns of behavior which manifest through alcohol consumption and other outwardly directed expressions. Though studies have shown genetic associations between PPG and externalizing disorders31, an internalizing pattern may also exist in PPG--individuals with PPG have reported uncomfortable mood states or anxiety relieved only by gambling, as well as similar feelings as losses mount. Consistently, a substantial correlation has been shown between genetic components of pathological gambling and internalizing disorders such as MDD32. If PPG can be characterized by internalizing characteristics, this may explain why fewer associations are seen between these Axis I disorders and gambling in individuals who have AUD, who may exhibit more “externalizing” behavior patterns in general. These data suggest the possibility of two distinct groups. A predominant group of individuals suffers from a consistent internalizing pattern of co-morbid disorders, such as PPG and MDD, while a second group of individuals predominantly suffers from an externalizing disorder such as AUD, which then contributes to the initiation or exacerbation of PPG through shared genetic influences and manifests behaviorally (e.g. as lack of constraint)24, 31. Future longitudinal studies will help to test this hypothesis.

It should be noted that the results from multivariable models are often governed by either particularly high rates among non-gambling ADD respondents, or particularly low rates among ADD recreational gamblers. For MDD and PD, while individuals with AUD and PPG have the lowest rates of these disorders compared to those without AUD, the prevalence rates are also highest in the non-gambling and lower-risk gambling AUD groups. For drug abuse/dependence, while the rates are uniformly higher in the AUD group, within that group they are also lowest in those with PPG. Several possible explanations exist regarding these findings. First, individuals with AUD may be using gambling to target internalizing psychopathology and thus a decrease in these symptoms is reported in PPG groups, affecting rates of depression and anxiety. Second, it may be that the stimulating effects of excessive gambling somehow `counteract' the depressant effects of excessive alcohol use, thereby lowering the likelihood of having an internalizing disorder such as depression or anxiety. Finally, there is a possibility that the presence of concurrent gambling and alcohol use problems mask the symptoms of other disorders that either share similar traits (e.g. anxiety symptoms related to withdrawal), or that cause symptoms to be discounted in the diagnostic algorithm as being the result of intoxication, thus making prevalence rates appear artificially low. With respect to drug abuse/dependence, it may be that those respondents spending significant amounts of time and money engaging in alcohol use and gambling do not have resources left to abuse drugs. In addition, it is easier to engage in alcohol use and gambling simultaneously, while presumably this is not the case for drug use.

The relationship between Axis II disorders follow the same general pattern as Axis I disorders in the patterns of their co-occurrence with AUD and gambling. Alcohol-by-gambling groups interactions were significant only in cases where a stronger association was observed between Axis II disorders and increasing gambling severity in the group without AUD. These findings suggest that personality patterns that are associated with propensities for increased gambling (e.g., antisocial personality disorder) do not have the same influence on gambling engagement in those with AUD, perhaps because motivational behaviors are preferentially directed towards alcohol consumption rather than gambling in individuals with AUD.

Replicating other studies that utilized the NESARC dataset, we found robust demographic differences between groups in this study10. Uniformly, these differences were less strong before adjusting for socio-demographic variables for our main analysis (data not shown). This may be due to additive effects of other demographic variables that significantly predict outcomes (e.g. gender and depression), that also differ across gambling groups, that when corrected for, lead to the stronger associations that we found.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our data provide several important insights. Gambling severity in adults without AUD was associated with a range of psychopathology, spanning mood, anxiety and substance disorders. Given the increased popularity and frequency of gambling in the US population, concern has been raised about the significant threat potentially posed by subsyndromal levels of gambling19. Additionally, there is a relative paucity of studies examining “low-risk” gambling patterns15. Our findings suggest significant associations between psychopathology and even low-risk gambling patterns, which have important implications for the medical community, where screening for gambling and other psychopathologies could be a standard part of clinical care. Additionally, these results could have public policy implications regarding the expansion of available gambling venues, particularly the availability of gambling to potentially vulnerable sub-populations such as adolescents, college students, those with mental illness, and the elderly.

Several limitations of these data should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to identify specific factors that might establish temporal relationships between disorders or mediate the above identified associations. Data collected in a longitudinal manner would help to address these issues. Additionally, as low rates of pathological gambling were reported, problem and pathological gambling needed to be combined into a single category. Though this has been done successfully in previous reports12, 33, it limits our ability to examine and distinguish those with the most severe spectrum of gambling-related problems. There were also low rates of some other psychiatric disorders, such as dependent personality disorder, precluding the ability to make clinically meaningful comparisons, whereas assessment measures of some other relevant Axis I and II disorders (other impulse control disorders, borderline personality disorder) were altogether lacking. Finally, though research is beginning to address this issue, no standards for categorization of gambling behavior across a continuum have been established. For example, we divided gambling groups into those without symptoms, 1–2 symptoms or 3+ symptoms which, though utilized in previous studies, are not based on empirically derived thresholds.

CONCLUSIONS

While prevalence rates of psychopathology are generally higher in respondents with AUD than in those without AUD, the relative associations among gambling groups are stronger in those without AUD. The reasons for this remain unclear. However, these results suggest that further work is needed on the etiology and course of these disorders, as well as how they inter-relate to each other in their presentation and effects on functional impairment. These data will help to inform conceptualization and treatment of these comorbid conditions in not only screening of gambling in particular patient populations, but in furthering our understanding of common neurological mechanisms of these disorders as well.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the following grants: T32-DA007238 (JAB), R01 DA019039 (MNP), R01 AA017539 (MNP), VA VISN1 MIRECC (MNP), and Women's Health Research at Yale (MNP and RAD).

Dr. Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr. Potenza consults for and is an advisor to Boehringer Ingelheim; has consulted for and has financial interests in Somaxon; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Veteran's Administration, Mohegan Sun, and Glaxo-SmithKline, Forest Laboratories, Ortho-McNeil and Oy-Control/Biotie pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for law offices and the federal public defender's office in issues related to impulse control disorders; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts; and provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures Drs. Brewer, Potenza and Desai have no competing interests to disclose with respect to the content of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Commission NGIS National Gambling Impact Study Commission Final Report. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petry NM, Kiluk BD. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002 Jul;190(7):462–469. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000022447.27689.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muelleman RL, DenOtter T, Wadman MC, Tran TP, Anderson J. Problem gambling in the partner of the emergency department patient as a risk factor for intimate partner violence. J Emerg Med. 2002 Oct;23(3):307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman SC, Thompson AH. A population-based study of the association between pathological gambling and attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2003 Spring;33(1):80–87. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.1.80.22785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB. The epidemiology of pathological gambling. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2001 Jul;6(3):155–166. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2001.22919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, 3rd, Spitznagel EL. Taking chances: problem gamblers and mental health disorders--results from the St. Louis Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Am J Public Health. 1998 Jul;88(7):1093–1096. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 May;66(5):564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and Co-occurrence of Substance Use Disorders and Independent Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Aug 1;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crockford DN, el-Guebaly N. Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: a critical review. Can J Psychiatry. 1998 Feb;43(1):43–50. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gender differences in the associations between past-year gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008 Mar;43(3):173–183. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petry N, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Co-morbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gender differences in the associations between gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0283-z. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai RA, Desai MM, Potenza MN. Gambling, health and age: Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007 Dec;21(4):431–440. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potenza MN, Maciejewski PK, Mazure CM. A Gender-based Examination of Past-year Recreational Gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 2005 Dec 22;:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-9002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Dausey DJ, Caldarone BJ, Potenza MN. Health correlates of recreational gambling in older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Sep;161(9):1672–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer HJ, Korn DA. Gambling and related mental disorders: a public health analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:171–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welte J, Barnes GM, Wieczorek WF, Tidwell MC, Parker J. Gambling participation in the U.S. -Results from a national survey. J Gambl Stud. 2002;18:313–338. doi: 10.1023/a:1021019915591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN. Updating and refining prevalence estimates of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada. Can J Public Health. 2001;92:168–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03404298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: A research synthesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1369–1376. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and Acuracy Statement for Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologuc Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, S.Chou P, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDASIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th, text revised ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Research Council . Pathological Gambling: A Critical Review. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slutske WS, Eisen S, True WR, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang M. Common genetic vulnerability for pathological gambling and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 Jul;57(7):666–673. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah KR, Eisen SA, Xian H, Potenza MN. Genetic studies of pathological gambling: a review of methodology and analyses of data from the Vietnam era twin registry. J Gambl Stud. 2005 Summer;21(2):179–203. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-3031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant JE, Potenza MN, Hollander E, et al. Multicenter investigation of the opioid antagonist nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):303–312. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamminga CA, Nestler EJ. Pathological gambling: focusing on the addiction, not the activity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):180–181. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welte J, Barnes G, Wieczorek W, Tidwell MC, Parker J. Alcohol and gambling pathology among U.S. adults: prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. J Stud Alcohol. 2001 Sep;62(5):706–712. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duhig AM, Maciejewski PK, Desai RA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Potenza MN. Characteristics of adolescent past-year gamblers and non-gamblers in relation to alcohol drinking. Addict Behav. 2007 Jan;32(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;56(10):921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potenza MN, Xian H, Shah K, Scherrer JF, Eisen SA. Shared genetic contributions to pathological gambling and major depression in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;62(9):1015–1021. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potenza MN, Desai RA, Grant JE. Influence of nicotine dependence on the associations between gambling and psychiatric disorders. Presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 12th annual meeting.2006. [Google Scholar]