Abstract

Rationale

Understanding the neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying dysregulated cocaine intake is important for the development of new cocaine-abuse therapies.

Objectives

The current study determined if cocaine escalation under extended access conditions (6-hr access) is regulated by discrimination learning processes.

Methods

Rats were initially trained on cocaine self-administration (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) using a fixed ratio 1 (FR 1) schedule under 1-hr access for 12 sessions. Some rats were then trained to self-administer cocaine under 1-hr or 6-hr access conditions exclusively for an additional 14 sessions, while other rats were trained under both 1- and 6-hr access conditions that were cued or noncued for an additional 28 sessions (14 sessions for 1- and 6-hr access). Two additional groups of rats were initially trained to self-administer cocaine using an FR 1 schedule under 10-min access for 12 sessions; half of the animals were then switched to 60-min access conditions for an additional 14 sessions.

Results

When access conditions were differentially cued, escalation of cocaine intake was evident in animals with both 1- and 6-hr access during the escalation phase. Escalation also was evident in animals initially trained with 10-min access and then switched to 60-min access.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that dysregulated and regulated intake can be expressed within the same animal, indicating that escalation is context-dependent. Furthermore, escalated cocaine intake can be expressed under 1-hr access conditions. Overall, these results suggest that escalated cocaine intake may be representative of a discrimination-dependent regulated intake process, rather than addiction-like, compulsive intake.

Keywords: Escalation, addiction, cocaine, acquisition, discrimination, context

The neuroadaptations that accompany escalated drug intake with continued use are thought to be the genesis of addiction (American Psychiatric Association [DSM-IV-TR], 2000); however, preclinical study of drug abuse typically has used limited access self-administration conditions that lead to steady regulated intake across time. These short, intermittent access conditions have served well in modeling the onset and maintenance of drug abuse, but they have not served as well in modeling the switch from recreational use to the dysregulated, compulsive use that characterizes the process of addiction (Everitt and Robbins 2005).

To understand the neuroadaptations that accompany addiction, there has been a push to design experiments in laboratory animals that model more closely dysregulated drug-taking behavior (Roberts, Morgan and Liu 2007). One key component of these designs has been the use of extended drug access conditions (Ahmed 2009). Although not the only method available (e.g., discrete-trial ‘binge’; Fitch and Roberts 1993; Roberts et al. 2002; Tornatzky and Miczek 2000), designs that incorporate extended access conditions have become used widely to model dysregulated intake. For example, Ahmed and Koob (1998; 1999) trained rats to self-administer cocaine initially on a fixed ratio 1 (FR 1) schedule of reinforcement across daily 1-hr sessions until stable responding was reached. Animals were then shifted to 6-hr sessions or were maintained on 1-hr sessions for an additional 21 training sessions. The 6-hr access group exhibited an increase in total cocaine intake over the 21-session training period, while the 1-hr access group maintained stable intake (Ahmed and Koob 1998; 1999). It was hypothesized that the escalation of cocaine intake in the 6-hr access group models the progressive increase in drug taking displayed by humans with substance use disorders and represents dysfunctional, compulsive drug intake.

Intake escalation during 6-hr sessions has been replicated many times with cocaine (e.g., Ahmed and Koob 1999; Ahmed et al. 2003; Ahmed and Koob 2004; Ahmed and Cador 2006). It has also been demonstrated with other drugs of abuse, including heroin (Ahmed et al., 2000), methamphetamine (Kitamura et al. 2006), amphetamine (Gipson and Bardo 2009), methylphenidate (Marusich et al. 2010), and phencyclidine (Carroll et al. 2005). While escalated intake with extended access is a robust and general phenomenon that occurs across multiple drug classes, there is debate about the underlying mechanisms responsible for intake escalation (Zernig et al. 2007). A number of neurobehavioral mechanisms have been suggested, including reward allostasis (Ahmed and Koob 2005), tolerance (Oleson and Roberts 2009), incentive sensitization (Berridge 2007), or habit formation (Everitt and Robbins 2005). In addition, neuroadaptations in the mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) and glutamate systems have been suggested as possible neurobiological components underlying these behavioral changes (e.g., Koob et al. 2004; Madayag et al. 2010). These neuroadaptations have been posited as relatively permanent changes that may account for the persistence of drug addiction and relapse (Kalivas and O’Brien 2008).

Recent evidence by Goeders et al. (2009) suggests that escalation under extended access conditions may be more representative of a general learning process than a process indicative of drug addiction. Using a liquid reinforcer with mice, Goeders et al (2009) demonstrated that escalation occurs when animals are given extended access to a non-drug reinforcer. Importantly, the authors demonstrated that post-escalation behavior with a non-drug reinforcer is comparable to that following escalation using a drug reinforcer. Like cocaine-reinforced behavior (Ferrario et al. 2005; Paterson and Markou 2003), breakpoints on a progressive ratio schedule for the sucrose reinforcer were elevated following escalation. In addition, like escalation using a cocaine reinforcer (Ferrario et al. 2005), animals that escalated sucrose intake were more sensitive to the psychomotor effects of cocaine. Although these results could be interpreted as a model of dysregulated food intake, they also raise the possibility that escalation may be a more general process related to normal learning and not, on its own, necessarily representative of dysfunctional, compulsive intake.

In the current study, we investigated the extent to which escalated cocaine intake is governed by regular processes of learning, as opposed to dysregulated behavior. First, we tested the context-dependence of escalated cocaine intake by differentially cueing short- and long-access conditions within individual animals. The hypothesized role of drug-associated cues in the development of addiction is highlighted by some theories of addiction (e.g., incentive sensitization; Robinson and Berridge 2008), and there is evidence of neuroadaptations that are specific to environments associated with cocaine self-administration (Edwards et al. 2011). However, the role of cocaine-associated context in differential access to cocaine self-administration is unknown. We hypothesized that, just as learned tolerance is context-dependent (Siegel 1976), animals would discriminate short from long access conditions and would express escalated intake only during the cued long-access conditions. Second, we investigated if escalated cocaine intake requires long access conditions per se or whether it simply reflects a normal adjustment in responding due to a change in the temporal context from acquisition session to escalation session (i.e., from 1- to 6-hr duration). We hypothesized that if escalated cocaine intake from 1- to 6-hr access reflects a change in temporal context, then animals trained initially on 10-min cocaine access should also show escalated intake when switched to 1-hr access, as the proportional change in temporal context is equivalent (6:1).

METHOD

Animals

Thirty-three adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Inc.; Indianapolis, IN, USA), weighing approximately 250–275 g at the beginning of experimentation, were used. Rats were housed individually in a temperature-controlled environment with a 14:10 hr light:dark cycle, with lights on at 0600 h. All experimentation was conducted during the light phase. Following acclimation, rats were food deprived to 85% of their free-feeding body weight and sufficient food was given daily to maintain this weight throughout experimentation. All rats had unrestricted access to water in their home cage. All experimental protocols were conducted according to the 1996 NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky.

Apparatus

All experiments were conducted using operant conditioning chambers (ENV-001; MED Associates, St. Albans, VT) housed within sound-attenuating compartments (ENV-018M, MED Associates). Each chamber was connected to a PC interface (SG-6080D, MED Associates) and were operated using MED-PC™ software. All chambers were equipped with a 5 cm × 4.2 cm recessed food receptacle, two retractable response levers that were mounted 7.3 cm above a metal rod floor on either side of the food receptacle, a house-light mounted on the opposite wall from the food receptacle, and two 28 v, 3-cm diameter, white cue lights mounted 6 cm above each response lever. Food pellets (45-mg Noyes Precision Pellets; Research Diets, Inc.; New Brunswick, NJ) were delivered with a pellet dispenser (ENV-203, MED Associates) mounted outside of the chamber. Cocaine infusions (0.1 ml over 5.9 s) were delivered through a watertight swivel (MED Associates) attached to a syringe pump (PHM-100, MED Associates) mounted outside the sound-attenuating compartment via tygon tubing that was attached to a head-mounted cannula.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl was a gift from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD, USA) and mixed in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl).

Surgery

Chronic indwelling silastic catheters were implanted into the jugular vein while under anesthesia (100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg diazepam, i.p.). The catheter was attached to a metal cannula affixed to the skull via 4 jeweler screws and dental acrylic.

Cocaine self-administration: Acquisition phase

Methods were similar to those published previously (Ahmed and Koob 1999), with minor changes. All animals were trained initially to lever press for food on a fixed ratio 1 (FR 1) schedule of reinforcement, where a food pellet was delivered following each press on the active lever (counterbalanced for side of the experimental chamber) and presses on the inactive lever had no consequence. Training consisted of 5 consecutive 1-hr sessions over 5 days. Immediately following food training, all animals were trained to self-administer cocaine on an FR 1 schedule using the same active/inactive lever assignment from food training, with a 20-s signaled time out (both cue lights were illuminated). Acquisition of cocaine self-administration continued for 12 consecutive sessions using a unit dose of 0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion and session duration of either 10 or 60 min, as described below.

Cocaine self-administration: Escalation phase

Between-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation

Immediately following the acquisition phase, animals were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Animals assigned to one group continued to self-administer cocaine under the 1-hr access conditions from acquisition for an additional 14 sessions. Animals assigned to the other group were switched to 6-hr access for an additional 14 sessions.

Within-subject cocaine (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) escalation, with cued session duration in escalation phase

Immediately following the 12 consecutive 1-hr sessions of cocaine self-administration (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) during acquisition, animals were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) under both 1-hr access and 6-hr access conditions for an additional 28 sessions (14 sessions of 1-hr access and 14 sessions of 6-hr access). Access conditions were differentially cued by illumination of the house-light (counterbalanced across animals). The first session of escalation training was counterbalanced for 1-hr or 6-hr access. The remaining training sessions alternated each day between 1-hr and 6-hr sessions.

Within-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation, without cued session duration in escalation phase

These methods were identical to those used above, except the alternating 1- and 6-hr session durations were not differentially cued; the houselight was either on or off for both access conditions (counterbalanced across animals).

Between-subject cocaine (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) escalation using 10-min training and 60-min escalation access conditions

During acquisition, animals were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) over 12 consecutive sessions as described previously, except the session duration was 10 min. Immediately following acquisition, animals were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Animals assigned to one group continued to self-administer cocaine under 10-min access conditions for an additional 14 sessions. Animals assigned to the other group were switched to 60-min access for an additional 14 sessions.

Analysis

For the experiments that manipulated access within subject, two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs, with session and access condition as within-subject factors, were used. For the experiments that manipulated access between subjects, two-way mixed-factor ANOVAs, with session as a within-subject factor and access condition as a between-subject factor, were used. Additionally, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to test for a main effect of escalation session within each access group or condition for all escalation data, including total responses, total responses from the 1st hour, and total responses from the 1st 10 min. Finally, due to the unusual 10-min access parameters used during initial 12-session cocaine self-administration acquisition training for the 10- vs. 60-min experiments, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, with session and lever (active vs. inactive) as within-subject variables, was used to test for acquisition. An additional one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used on the data from the last three 10-min acquisition sessions to determine stability of self-administration. All contrasts were carried out using Tukey HSD.

RESULTS

Between-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation

Unlike animals that self-administered cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) under 1-hr access for the entire experiment (i.e., acquisition and escalation phase), animals switched to 6-hr access increased the number of infusions earned over the 14-session escalation-training period (Fig. 1A). ANOVA revealed main effects of access duration [F(1,13) = 26.88, p < 0.05] and session [F(13,169) = 6.93, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access duration x session interaction [F(13,169) = 6.79, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of session on infusions for the 6-hr access group [F(13,91) = 8.07, p < 0.05], but not for the 1-hr access group. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to day 1 for the 6-hr group, infusions were significantly higher on sessions 9–14.

Fig 1.

(A) Between-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose for 1-hr (n = 7) and 6-hr (n = 8) access groups. Asterisk (*) represents significant difference in session infusions, relative to session 1 (p < 0.05). (B) First-hour total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for 1-hr and 6-hr access groups. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions (p < 0.05). (C) Time course (5-min bins) for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the 1-hr access group. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05). (D) Time course for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the 6-hr access group. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05).

Total infusions during the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 increased as a function of session for the 6-hr group, but not for the 1-hr group (Fig. 1B). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of access duration [F(1,13) = 7.25, p < 0.05] and session [F(1,13) = 10.56, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access duration x session interaction [F(1,13) = 10.30, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a main effect of session on infusions for the 6-hr access group [F(1,7) = 33.93, p < 0.05], but not for the 1-hr access group. Additionally, time course results during the first hour in the escalation phase showed that cocaine infusions were higher on session 14 relative to session 1 only for the 6-hr access group (Fig. 1C and 1D). ANOVA on infusions during the first hour from the 6-hr access group on sessions 1 and 14 revealed only a significant main effect of session [F(1,7) = 33.93, p < 0.05]. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA on infusions during the first hour from the 1-hr group revealed no significant effects.

Within-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation, with cued session duration in escalation phase

When animals were given alternating exposure to 1- and 6-hr access conditions using differential cues in the escalation phase, cocaine infusions (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) increased only during 6-hr access sessions (Fig. 2A). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of access duration [F(1,6) = 66.35, p < 0.05] and session [F(13,78) = 3.67, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access duration x session interaction [F(13,78) = 3.84, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session on infusions for the 6-hr access condition [F(13,78) = 3.74, p < 0.05], but not for the 1-hr access condition. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that infusions were significantly higher on sessions 6, 8, and 10–14 relative to session 1 in the 6-hr condition.

Fig 2.

(A) Within-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose with differential stimulus cues for 1- and 6-hr access conditions. Asterisk (*) represents significant difference in session infusions, relative to session 1 (p < 0.05). (B) First-hour total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for differentially cued 1-hr and 6-hr access conditions. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions (p < 0.05). (C) Time course (5-min bins) for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the cued 1-hr access condition. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05). (D) Time course for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the cued 6-hr access condition. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05). n = 7

Total infusions from the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 increased as a function of session for 6-hr condition, but not the 1-hr condition (Fig. 2B). ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session [F(1,6) = 7.18, p < 0.05] and a significant access duration x session interaction [F(1,6) = 7.0993, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of session for the 6-hr condition [F(1,6) = 8.32, p < 0.05), but not for the 1-hr condition. Furthermore, time course results during the first hour in the escalation phase showed that cocaine infusions were higher on session 14 relative to session 1 in the 6-hr condition, but not the 1-hr condition (Fig. 2C and 2D). ANOVA on data from the 6-hr condition revealed only a main effect of session [F(1,6) = 8.32, p < 0.05] on cocaine infusions within the first hour of 6-hr access conditions. ANOVA on time course data from the 1-hr access condition revealed no significant main effects or interaction.

Within-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation, without cued session duration in escalation phase

When animals had alternating access between 1-hr and 6-hr sessions without differential cues for each access condition, cocaine infusions (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) did not change across either the 1-hr or 6-hr access conditions (Fig. 3A). ANOVA revealed only a main effect of access condition [F(1,5) = 47.46, p < 0.05]. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of session for either the 6-hr or the 1-hr condition.

Fig 3.

(A) Within-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose without differential stimulus cues for 1- and 6-hr access conditions. (B) First-hour total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for non-differentially cued 1-hr and 6-hr access conditions. (C) Time course (5-min bins) for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the non-differentially cued 1-hr access condition. (D) Time course for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the non-differentially cued 6-hr access condition. n = 6.

Total infusions within the first hour did not change as a function of session (Fig. 3B). ANOVA revealed no main effects or interaction. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of session for either the 6-hr or the 1-hr condition. Furthermore, time course results during the first hour in the escalation phase showed that cocaine infusions did not change from session 1 to 14 for either access condition (Fig. 3C and 3D). ANOVA revealed no significant main effect or interaction with either 1-hr or 6-hr conditions.

Within-subject cocaine escalation using higher unit dose (0.25 mg/kg/infusion), with cued session duration in escalation phase

Similar to the results obtained with the lower unit dose of cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion), when animals were given alternating exposure to 1- and 6-hr access conditions using differential cues in the escalation phase, cocaine infusions (0.25 mg/kg/infusion) increased only during 6-hr sessions (Fig. 4A). ANOVA indicated significant main effects of access duration [F(1,5) = 221.25, p < 0.05] and session [F(13,65) = 3.46, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access duration x session interaction [F(13,65) = 3.67, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session for the 6-hr condition [F(13,65) = 3.70, p < 0.05], but not for the 1-hr condition. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that, relative to session 1, infusions were significantly higher on sessions 5–14 in the 6-hr condition.

Fig 4.

(A) Within-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at a 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose with differential stimulus cues for 1- and 6-hr access conditions. Asterisk (*) represents significant difference in session infusions, relative to session 1 (p < 0.05). (B) First-hour total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for differentially cued 1-hr and 6-hr access conditions at the 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions (p < 0.05). (C) Time course (5-min bins) for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the cued 1-hr access condition at the 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05). (D) Time course for cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) across the first hour on sessions 1 and 14 for the cued 6-hr access condition at the 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose. Asterisk (*) represents significant differences in total infusions between session 1 and 14 (p < 0.05). n = 6.

Total infusions within the first hour increased as a function of session for the 6-hr group only (Fig. 4B). ANOVA revealed only a significant access duration x session interaction [F(1,5) = 24.53, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session for the 6-hr condition [F(1,5) = 7.71), p < 0.05], but not for the 1-hr condition. Furthermore, time course results during the first hr in the escalation phase showed that cocaine infusions were higher on session 14 relative to session 1 only across 6-hr sessions (Fig. 4C and 4D). ANOVA on data from the 6-hr access condition revealed a main effect of session [F(1,5) = 7.71, p < 0.05] and a significant session x time interaction [F(11,55) = 3.67, p < 0.05]. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to session 1, cocaine infusions were higher during session 14 at time points 35 – 60 min, except at time point 40 min. ANOVA on data from the 1-hr access condition revealed only a significant main effect of time [F(11,55) = 3.06, p < 0.05].

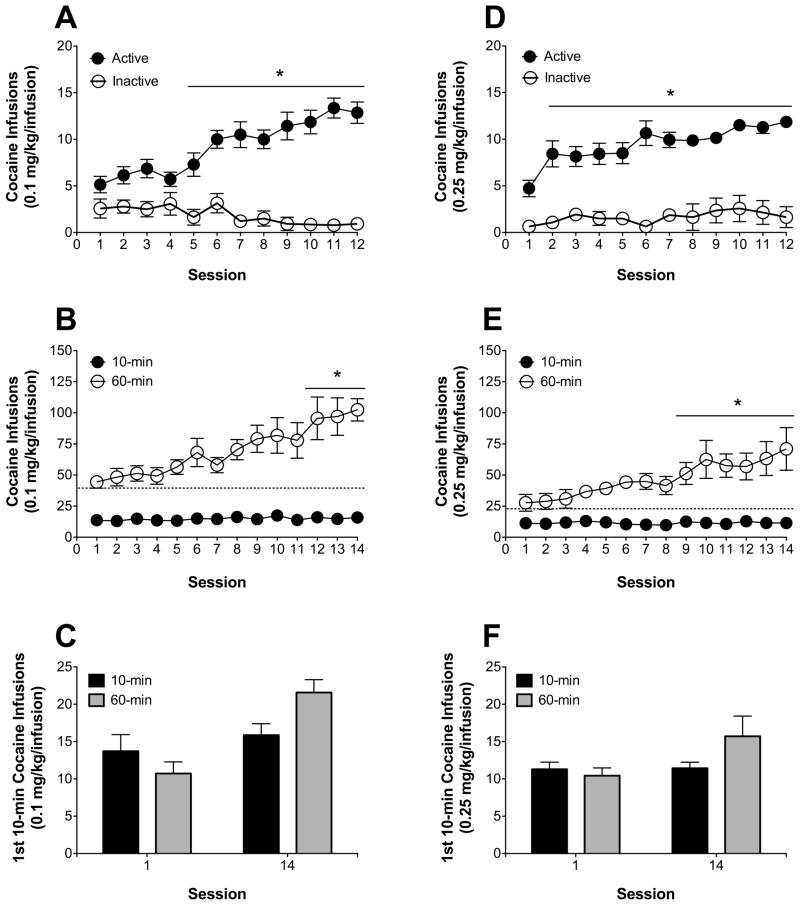

Between-subject cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) escalation using 10-min training and 60-min escalation access conditions

Over the initial 10-min acquisition sessions using the 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose of cocaine, responding increased on the active lever, but not on the inactive lever (Fig. 5A). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of session [F(11, 143) = 4.87, p < 0.05] and lever [F(1,13) = 126.13, p < 0.05], as well as a significant session x lever interaction [F(11,143) = 12.01, p < 0.05]. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to inactive lever presses, active lever presses were higher on sessions 5–12. One-way repeated measures ANOVA on the last three 10-min sessions revealed no significant main effect of session, indicating that active lever pressing was stable by the end of the 12-session acquisition phase.

Fig 5.

(A) Acquisition of cocaine self-administration for 10-min training sessions at a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose (n = 14). Asterisk (*) represents significant differences between active and inactive lever presses (p < 0.05). (B) Between-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose for 10-min (n = 7) and 60-min (n = 7) access groups. Asterisk (*) represents significant difference in session infusions, relative to session 1 (p < 0.05). (C) First-10 min total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for 110-min and 60-min access groups at the 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose. (D) Acquisition of cocaine self-administration for 10-min training sessions at a 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose (n = 14). Asterisk (*) represents significant differences between active and inactive lever presses (p < 0.05). (E) Between-subject escalation of total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) at 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose for the 10-min (n = 7) and 60-min (n = 7) access groups. Asterisk (*) represents significant difference in session infusions, relative to session 1 (p < 0.05) (F) First-10 min total cocaine infusions (Mean ± SEM) from sessions 1 and 14 for 110-min and 60-min access groups at the 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose.

When animals were initially trained to self-administer cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) under 10-min access conditions, escalated intake was demonstrated in animals switched to the 60-min access, but not in animals maintained on 10-min access (Fig. 5B). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of access group [F(1,12) = 63.99, p < 0.05] and session [F(13,156) = 5.79, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access group x session interaction [F(13,156) = 4.93, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session for the 1-hr group [F(13,78) = 5.47, p < 0.05], but not for the 10-min group. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to session 1 for the 1-hr group, infusions were higher on sessions 12–14. Furthermore, cocaine infusions during the first 10 min of the 10-min access group did not change over the escalation phase, while cocaine infusions escalated during the first 10 min of the 60-min access group (Fig. 5C). ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session [F(1,12) = 31.17, p < 0.05] and a significant access duration x session interaction [F(1,12) = 14.01, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session on the first 10-min infusion totals for the 1-hour group [F(1,6) = 27.37, p < 0.05], but not for the 10-min group.

Between-subject cocaine escalation at higher unit dose (0.25 mg/kg/infusion), using 10-min training and 60-min escalation access conditions

Like animals trained with the 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose, over the initial 10-min acquisition sessions using the 0.25 mg/kg/infusion unit dose of cocaine, responding increased on the active lever only (Fig. 5D). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of session [F(11, 143) = 5.28, p < 0.05] and lever [F(1,13) = 84.27, p < 0.05], as well as a significant session x lever interaction [F(11,143) = 2.50, p < 0.05]. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to inactive lever presses, active lever presses were higher on sessions 2–12. One-way repeated measures ANOVA on the last three 10-min sessions revealed no significant main effect of session, indicating that active lever pressing was stable by the end of the 12-session acquisition phase.

Similar to the lower unit dose (0.1 mg/kg/infusion), animals that were initially trained to self-administer cocaine at a higher unit dose (0.25 mg/kg/infusion) under 10-min access conditions and switched to 60-min access, escalated intake over sessions, relative to animals maintained on 10-min access throughout training (Fig. 5E). ANOVA revealed significant main effects of access group [F(1,12) = 44.80, p < 0.05] and session [F(13,156) = 2.86, p < 0.05], as well as a significant access group x session interaction [F(13,156) = 2.80, p < 0.05]. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session for the 1-hr group [F(13,78) = 2.84, p < 0.05], but not for the 10-min group. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, relative to session 1 for the 1-hr group, infusions were higher on sessions 9–14. Furthermore, cocaine infusions during the first 10 min of the 10-min access group did not change over the escalation phase, while cocaine infusions escalated during the first 10 min of the 60-min access group (Fig. 5F). ANOVA revealed a trend toward significant main effect of session [F(1,12) = 4.14, p = 0.06] and access duration x session interaction [F(1,12) = 3.72, p = 0.07]. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session on the first 10-min infusion totals for the 1-hour group [F(1,6) = 6.20, p < 0.05], but not for the 10-min group.

DISCUSSION

The present experiments provide at least two important details regarding escalated cocaine intake when rats are switched from short- to long-access sessions. First, assuming that escalation is a measure of uncontrolled, dysregulated intake, these experiments demonstrate that regulated and dysregulated cocaine intake can be demonstrated in the same animal. When an animal is given access to cocaine under both limited (1-hr) and extended (6-hr) access conditions on alternating occasions, escalated intake is present only when these access conditions are differentially signaled, suggesting that the neuroadaptations that underlie addiction are dynamic and environment-dependent (cf. Edwards et al. 2011). Like previous research (Wee et al. 2007), this cue-dependent escalation was dose-sensitive, with greater magnitude of escalation at a lower dose. Second, these experiments demonstrate that escalated intake can be observed during 1-hr access sessions, if animals are initially trained under a 10-min access session. The escalation observed during 60-min sessions does not likely reflect a failure of animals to acquire self-administration during the 10-min acquisition phase, as all animals trained with this duration demonstrated stable responding and lever discrimination (active vs inactive) by the end of the training phase (see Fig. 5A and 5D). Instead, these latter results suggest that escalation may reflect an intake acquisition process that depends on discriminating a change in temporal context when switching from a short access to long access session. Collectively, these results indicate that escalation of cocaine self-administration under the current procedures may represent normal discrimination learning, rather than dysregulated, addiction-like behavior.

During 6-hr sessions with the lower unit dose of cocaine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion), there was no evidence of a ‘loading’ effect, where intake is higher early in the session and gradually decreases to an asymptote over the rest of the session. To the contrary, animals demonstrated steady responding throughout the session when trained with this unit dose, regardless of whether extended access was manipulated between- or within-subject. The only published study reporting the use of a 0.1 mg/kg/infusion unit dose of cocaine during escalation training is Gipson et al. (2011). The within-session intake pattern from that study also found that intake was relatively constant throughout the session. In general, it appears that a unit dose of 0.1 mg/kg/infusion does not result in the same within-session intake pattern as higher unit doses (e.g., 0.25 mg/kg/infusion). This result is consistent with the idea of titration around a satiety threshold (Tsibulsky and Norman 1999), where it would be expected that animals with access to lower cocaine doses would need to self-infuse cocaine more often to maintain a satiety point, resulting in steady rates across the self-administration session.

The present results are in general agreement with those of Goeders et al. (2009), who found that escalated intake could be obtained with a liquid sucrose reinforcer. Although this previous finding could be interpreted as potential evidence of dysregulated sucrose intake, it also raises the possibility that escalation is indicative of a general learning process. The present results extend this conclusion to a cocaine reinforcer and suggest that escalation may be a type of normal acquisition present during transitions from initial acquisition to escalation contexts that are temporally distinct. Goeders et al. (2009) also demonstrated that post-escalation responding on a PR schedule and sensitivity to cocaine-induced hyperactivity was comparable to that seen following escalation using a cocaine reinforcer (Paterson and Markou 2003; Ferrario et al. 2005). In light of these results, one might expect that following escalation with differentially cued access conditions, increases in breakpoint for cocaine should only be present when long-access cues are present. Furthermore, following escalation using the 10- and 60-min parameters, increases in breakpoints for cocaine should only be present in animals allowed 60-min access during the escalation phase. Future experiments are necessary to determine whether or not these predictions are correct. In addition, future research is necessary to determine if the neuroadaptive changes that are present in animals that exhibit escalated intake during 6-hr cocaine access (Koob et al. 2004) also are present in animals that exhibit escalation with a non-drug reinforcer or in animals that exhibit escalation when switched from 10- to 60-min cocaine access sessions. Finally, given that escalated intake is expressed only under extended access conditions that are cued, future research is necessary to determine if the neuroadaptive changes that accompany escalated cocaine intake are differentially expressed using discrete cues to signal short- vs. long-access conditions, similar to the effects found on extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity within cocaine-associated contexts (Edwards et al. 2011).

In addition to the context dependency provided by a discrete cue, escalation of drug infusions by animals switched from 10- to 60-min or from 1- to 6-hr access suggests that escalation may result from the discrimination of a change in temporal context (i.e., change in session length from the initial training phase to the escalation phase). The increase in intake upon the change in temporal context during escalation resembles the increase in intake during the initial acquisition phase. For example, when animals are first switched to the initial 1-hr cocaine self-administration sessions, intake starts out low, but with repeated training it increases to a stable asymptotic level. Likewise, when animals are switched from initial 1-hr cocaine self-administration sessions to 6-hr access sessions, cocaine intake during the first few sessions starts out low, but with repeated training under 6-hr conditions intake increases to stable asymptotic levels, even beyond 50 sessions of training (Ahmed and Koob 1999). If intake escalation within extended access is indicative of a dysregulated process that leads toward a downward spiral of addiction (Koob et al. 2004), it might be expected that escalation would continue with extended training, rather than reaching a stable asymptote. Asymptotic intake implies regulation, not dysregulation. Thus, given that initial acquisition and escalation produce stable asymptotic intake levels, these stages may be representative of a similar process. Specifically, escalation may be a form of intake acquisition, expressed during the discrimination of changes in temporal context from initial acquisition (10-min or 1-hr sessions) to escalation (1- or 6-hr sessions).

Finally, it is well known that discrimination of changes in time obey Weber’s law (Gibbon et al. 1984), where a perceived change in duration is proportional to the value of the original duration. For example, the proportional change in temporal context from 1- to 6-hr is the same as from 10- to 60-min (6-to-1). Thus, the perceived change in temporal context between these conditions should be equivalent. Given that cocaine escalation was observed under both of these conditions suggests that escalated intake is a function of perceivable changes in temporal context. Wee et al. (2007) demonstrated that rats initially trained on 1-hr cocaine self-administration sessions and then switched to 3-hr sessions did not demonstrate escalation of cocaine intake, while rats that were switched to either 6-hr or 12-hr sessions exhibited cocaine intake escalation. Thus, a 3-to-1 change in time was not sufficient to promote escalation, but a 6-to-1 or 12-to-1 change was. This is consistent with the findings of the current report in which animals initially trained on 10-min access and then switched to 60-min access demonstrated escalated intake, as the access difference ratio is maintained at 6-to-1. According to this hypothesis, if animals were initially trained with 10-min access and then switched to 30-min access, escalation should not be observed (a 3-to-1 access ratio); likewise, if animals were initially trained on 6-hr access and then switched to 12-hr access, escalation should not be observed (a 2-to-1 access ratio). Further research is needed to determine if these predictions based on temporal discrimination are correct.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse [P50 DA05312 and T32 DA01617]

References

- Ahmed SH. Escalation of drug use. In: Olmstead MC, editor. Neuromethods: Animal models of drug addiction. The Humana Press Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Cador M. Dissociation of psychomotor sensitization from compulsive cocaine consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):563–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science. 1998;282 (5387):298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Long-lasting increase in the set point for cocaine self administration after escalation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146(3):303–312. doi: 10.1007/s002130051121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Changes in response to dopamine receptor antagonists in rats with escalating cocaine intake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172(4):450–454. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition to drug addiction: a negative reinforcement model based on an allostatic decrease in reward function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180(3):473–490. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Lin D, Koob GF, Parsons LH. Escalation of cocaine self-administration does not depend on altered cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens dopamine levels. J Neurochem. 2003;86(1):102–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H, Walker JR, Koob GF. Persistent increase in the motivation to take heroin in rats with a history of drug escalation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(4):413–421. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191(3):391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Batulis DK, Landry KL, Morgan AD. Sex differences in the escalation of oral phencyclidine (PCP) self-administration under FR and PR schedules in rhesus monkeys. 2005;180(3):414–426. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):384–396. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Bachtell RK, Guzman D, Whistler KN, Self DW. Emergence of context-associated GluR(1) and ERK phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens core during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration. Addict Biol. 2011;16(3):450–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario CR, Gorny G, Crombag HS, Li Y, Kolb, Robinson TE. Neural and behavioral plasticity associated with the transition from controlled to escalated cocaine use. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(9):751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch TE, Roberts DC. The effects of dose and access restrictions on periodicity of cocaine self-administration in the rat. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90053-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH. Scalar timing in memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;423:52–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson CD, Bardo MT. Extended access to d-amphetamine self-administration increases impulsive choice in a delay discounting task in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;207(3):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1667-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson CD, Beckmann JS, El-Maraghi S, Marusich JA, Bardo MT. Effect of environmental enrichment on escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214(2):557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders JE, Murnane KS, Banks ML, Fantegrossi WE. Escalation of food-maintained responding and sensitivity to the locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, O’brien C. Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(1):166–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura O, Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF, Pulvirenti L. Escalation of methamphetamine self administration in rats: a dose effect function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186(1):48–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, Boutrel B, Chen SA, Kenny PJ, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27(8):739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24(2):97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madayag A, Kau KS, Lobner D, Mantsch JR, Wisniewski S, Baker DA. Drug-induced plasticity contributing to heightened relapse susceptibility: neurochemical changes and augmented reinstatement in high-intake rats. J Neurosci. 2010;30(1):210–217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1342-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Beckmann JS, Gipson CD, Bardo MT. Methylphenidate as a reinforcer for rats: contingent delivery and intake escalation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(3):257–266. doi: 10.1037/a0019814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson EB, Roberts DC. Behavioral economic assessment of price and cocaine consumption following self-administration histories that produce escalation of either final ratios or intake. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):796–804. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Markou A. Increased motivation for self-administered cocaine after escalated cocaine intake. Neuroreport. 2003;14(17):2229–2232. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312020-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Brebner K, Vincler M, Lynch WJ. Patterns of cocaine self-administration in rats produced by various access conditions under a discrete trials procedure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67(3):291–299. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Morgan D, Liu Y. How to make a rat addicted to cocaine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(8):1614–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S. Morphine analgesic tolerance: its situation specificity supports a Pavlovian conditioning model. Science. 1976;194(4250):323–325. doi: 10.1126/science.935870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Cocaine self-administration “binges”: transition from behavioral and autonomic regulation toward homeostatic dysregulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;148(3):289–298. doi: 10.1007/s002130050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibulsky VL, Norman AB. Satiety threshold: a quantitative model of maintained cocaine self-administration. Brain Res. 1999;839(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee S, Specio SE, Koob GF. Effects of dose and session duration on cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320(3):1134–1143. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernig G, Ahmed SH, Cardinal RN, Morgan D, Acquas E, Foltin RW, Vezina P, et al. Explaining the escalation of drug use in substance dependence: models and appropriate animal laboratory tests. Pharmacology. 2007;80(2–3):65–119. doi: 10.1159/000103923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]