Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between hyperglycemia and outcome in infants and children after severe traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Design

Retrospective review of a prospectively-collected Pediatric Neurotrauma Registry

Setting and Patients

Children admitted after severe TBI (post-resuscitation GCS ≤ 8) were studied (1999 – 2004). A subset of children (n = 28) were concurrently enrolled in a randomized, controlled clinical trial of early hypothermia for neuroprotection

Interventions

Demographic data, serum glucose concentrations and outcome assessments were collected

Methods and Main Results

Children (n = 57) were treated with a standard TBI protocol. Exogenous glucose was withheld for 48 h after injury unless hypoglycemia was observed (blood glucose < 70 mg/dl). Early (first 48 h) and Late (49 - 168 h) time periods were defined and mean blood glucose concentrations were calculated. Additionally, children were categorized based on peak blood glucose concentrations during each time period (normal (NG) – blood glucose < 150 mg/dl; mild hyperglycemia (MHG) – blood glucose ≤ 200 mg/dl; severe hyperglycemia (SHG) – blood glucose > 200 mg/dl). In the Late period, an association between elevated mean serum glucose concentration and outcome was observed (133.5 ± 5.6 mg/dl in the unfavorable group vs. 115.4 ± 4.1 mg/dl in favorable group, p = 0.02). This association continued to be significant after correcting for injury severity, age, and exposure to insulin (p = 0.03). Similarly, in the Late period, children within the SHG had decreased incidence of good outcome compared to children within the other glycemic groups (% good outcome: NG – 61.9%, MHG – 73.7%, SHG – 33.3%; p = 0.05). However, when adjusted for exposure to insulin, this relationship was no longer statistically significant.

Conclusions

In children with severe TBI, hyperglycemia beyond the initial 48 hours is associated with poor outcome. This relationship was observed in both our analysis of mean blood glucose concentrations as well as amongst the patients with episodic severe hyperglycemia. This observation suggests a relationship between hyperglycemia and outcome from TBI. However, only a prospective study can answer the important question, whether manipulating serum glucose concentration can improve outcome after TBI in children

Introduction

Study of the impact of hyperglycemia and optimal approaches to glucose control in pediatric critical care medicine as a whole has been the subject of considerable recent investigation and controversy (1-6). Despite the morbidity and mortality associated with TBI in infants and children, the relationship between hyperglycemia and outcome - and the optimal approach to glucose administration - has been the subject of only limited investigations in TBI (7-12).

In general, critical illness-induced hyperglycemia has been suggested to produce deleterious effects via alterations in immune function and increased incidence of infections (13-15), changes in inflammation (16), alterations in endothelium integrity (17), and compromising mitochondrial function (18). After TBI, however, CNS and systemic metabolic demands are interrelated and complex, while optimal glycemic control and/or nutritional support are extremely controversial. Many studies in experimental models of ischemic brain injury have shown that hyperglycemia is deleterious at or early after the time of injury, with serum glucose concentrations greater than ∼180 mg/dL demonstrating markedly exacerbated brain injury from various mechanisms including lactate accumulation, edema, and oxidative stress (19). In experimental TBI, fasting for 48 h – thereby minimizing the development of post-TBI hyperglycemia – is associated with favorable outcome (20). This effect is also reproduced by the administration of ketones, suggesting alternative fuel sources may be available and useful. On the other hand, early after TBI, glucose utilization is markedly altered related to a number of mechanisms including mitochondrial failure (21), hyperglycolysis related to glutamate uptake (22), hypoperfusion and/or ischemia related increases in glycolysis (23), and increases in brain tissue levels of lactate have been shown to persist for days after TBI in infants and children (24).

The majority of clinical investigations attempting to link glucose metabolism with neurological outcome after TBI have used serum/blood glucose concentrations as a surrogate marker. For adult TBI victims, admission hyperglycemia (variously defined) has been associated with poor outcome (25-28), with the stress-response and catecholamine release postulated as the root cause of this association (26). Prevention of hyperglycemia with either withholding of glucose and/or tight glucose control with intensive insulin therapy in adults after TBI has been suggested to confer substantial benefits including reduced vasopressor need to maintain CPP, reduced seizure frequency and prevention of diabetes insipidus (29). In contrast, Vespa et al demonstrated that tight glucose control in adults with severe TBI was associated with metabolic crisis in the brain as assessed by intracerebral microdialysis, including increases in lactate/pyruvate levels and decreases in brain interstitial glucose levels (30). Data in children with severe TBI on the relationship between hyperglycemia and outcome are limited. Parish reported that admission hyperglycemia (blood glucose concentration ≥ 270 mg/dL) was not associated with poor outcome in a small series of children (n = 36)(31). Still others have demonstrated some correlation between early hyperglycemia, severity of injury, and outcome (7-10). In addition, two key limitations of these studies is the lack of protocolized administration of glucose and limited information regarding the timing of the hyperglycemic episodes.

Our goal was to determine the relationship between serum glucose levels and neurological outcome after severe TBI in infants and children. Given that we have led several clinical trials in severe TBI that required a protocolized approach to care, we adopted a standard approach to caring for all children which includes frequent assessments of blood glucose concentrations and delayed administration of glucose until 48 hours after TBI to avoid early hyperglycemia. In our institution, we have adopted the practice of limiting glucose administration early after TBI – a common practice in institutions caring for adult TBI victims – which may be less common in other pediatric centers. Using this approach, we explored the relationship between either average glucose concentrations or a priori defined levels of hyperglycemia and outcome after severe TBI in infants and children.

Methods

Patient Selection and Treatment Protocol

Children admitted to Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh with severe TBI (GCS ≤ 8) were eligible for this study from 1999 - 2004. All children were enrolled in a prospectively collected Pediatric Neurotrauma Registry, in which demographic, physiological and other data were extracted from the medical record. A subset of children was concurrently enrolled in a Phase II trial of early hypothermia as neuroprotectant (32). Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh and all children had informed consent obtained in accordance with University policy.

All children were treated with a comprehensive protocol for management of severe TBI intended to minimize secondary injuries(32). As a part of this protocol, glucose administration was avoided for the 48 hours after TBI unless serum glucose < 70 gm/dl was observed. Serum glucose determinations were obtained frequently as part of our normal practice, but precise timing of glucose testing was done at the discretion of the clinical team. At 48 hours after injury, intravenous fluids with 5% dextrose were started. The route of nutritional support, parenteral or enteral, was determined by the clinical team and generally initiated on day 3. Protocolized insulin therapy was not utilized during the study period and insulin was administered at the discretion of the clinical team. For management of intracranial hypertension and general clinical care, a protocol based on the Guidelines for Medical Management of Severe TBI in Children. In general, a tiered approach to treatment of intracranial hypertension was utilized including positional maneuvers (head of bed to 30°, neck in midline), continuous CSF diversion, sedation, neuromuscular blockade, osmolar therapies (mannitol and/or hypertonic (3%) saline) and pentobarbital. Additional maneuvers, including rescue therapy with hypothermia and decompressive craniectomy, were performed in select cases of intractable intracranial hypertension.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Both bedside and laboratory determinations of serum glucose measurements were extracted from the medical record and included in the analysis. Serum glucose was collected via arterial lines and both point-of-care bedside and laboratory glucose determinations were collected for analysis. Medical records (both standard hospital records and an electronic database maintained by the Pharmacy Department) were interrogated to determine if insulin was administered during the study period. Using this methodology in our retrospective review, timing of insulin administration was not possible. Therefore, for all of the analyses of insulin within this paper, exposure to insulin during the study period was treated as a categorical variable. Glasgow outcome scale scores were determined at 6 months and dichotomized into favorable (GOS = 1 - 2) and unfavourable (GOS = 3 – 5).

For statistical analysis, two time periods were defined a priori - Early (first 48 hours after injury) and Late (49 - 168 hours after injury). This stratification was made because (i) temporal derangements in glucose concentrations may reflect different pathophysiological processes and (ii) exposure to exogenous glucose was different during these two time periods. Two separate analyses of serum glucose concentrations were performed. In Analysis 1, mean blood glucose concentrations were calculated for each patient during each period, as has been reported by others (8, 10). In Analysis 2, peak serum glucose concentrations were determined for each child during the two time periods and children were categorized into 3 glycemic groups based upon their peak blood glucose [normal (NG) – peak glucose < 150 mg/dL; mild hyperglycemia (MHG) – peak glucose ≤ 200 mg/dL; severe hyperglycemia (SHG) – peak glucose > 200 mg/dL], consistent with prior studies (7, 11-12). In separate analyses, (i) the relationship between hypoglycemia and outcomes (defined as a single glucose determination less than 50 mg/dl (11)), (ii) data regarding glucose values after abusive head trauma (AHT) within the study period and (iii) the glucose data regarding children who died was described.

Descriptive statistics (means ± SEM for parametric data, medians [ranges] for non-parametric data) were determined using commercially-available software (Sigma Stat; Systat Software, Inc; San Jose CA) for data within both analysis 1 and 2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted and all serum glucose concentrations are expressed in mg/dl. For both analysis 1 and 2, potential confounding factors were evaluated to determine if they (sex, race, hypo/normothermia, age, exposure to insulin, Injury Severity Score (ISS) or Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score) affected the relationship between glucose and outcome. Any potential confounding variable with a p < 0.1 was further interrogated in a multivariable regression analysis. All regression analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). Statistical significant was defined by a p value of less than 0.05.

Results

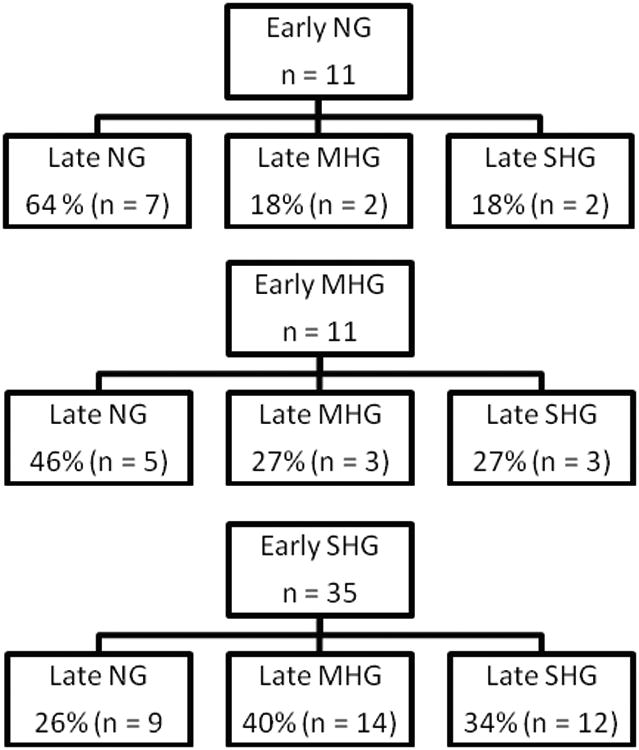

Fifty seven children were enrolled with a total of 2746 blood glucose measurements obtained (48.2 ± 3.3 measurement per child) during the study period. A majority of children were male (62%), the average length of stay was 22.5 ± 1.8 days and 91.6% survived to hospital discharge (Table 1). The relationship between the glycemic groups in the Early and Late period is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

| Demographic Information | N=57 |

|---|---|

| Age (in mo), (mean ± SEM) | 81 ± 7 |

| Male (%) | 62.1 |

| Caucasian (%) | 84.5 |

| Admission GCS, median (range) | 6 (3, 10) |

| Admission ISS, median (range) | 26 (10, 43) |

| Hypothermia (%) | 48.3 |

| Length of Stay (d), mean ± SEM) | 22.5 ± 1.8 |

| GOS | 2.31 |

| Mortality (%) | 8.6 % |

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing the relationship between glycemic stratification in the Early and Late time periods [definitions of glycemic strata: normal (NG) – peak glucose < 150 mg/dL; mild hyperglycemia (MHG) – peak glucose ≤ 200 mg/dL; severe hyperglycemia (SHG) – peak glucose > 200 mg/dL].

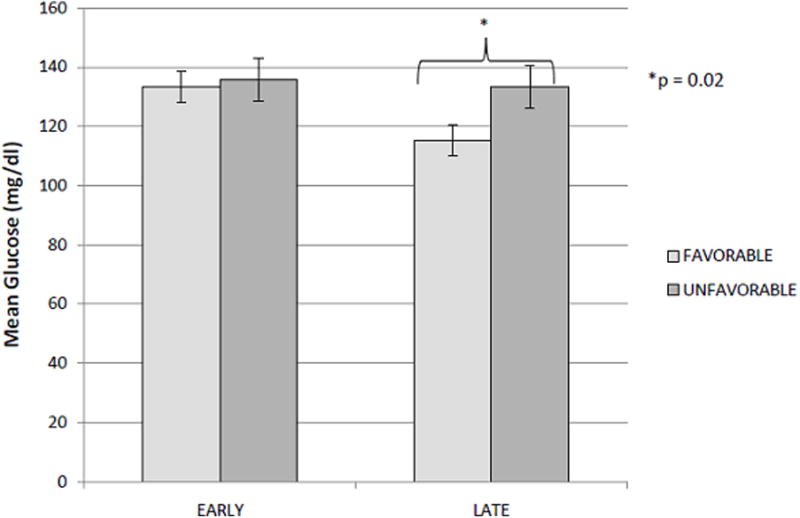

For Analysis 1, mean serum glucose concentrations in the Early period were similar in children with favorable and unfavorable outcomes (133.3 ± 5.2 vs. 135.7 ± 7.3, respectively, p = 0.72, Figure 2). However, in the Late period, an association between elevated mean serum glucose concentrations and poor outcome was observed (133.5 ± 5.6 vs. 115.4 ± 4.1, p = 0.02, Figure 2). In the Early period, univariate analyses identified age, ISS and exposure to insulin as potential confounders (Table 2). After adjustments for these factors, there remained no differences between glucose values in outcome groups (p = 0.72). Similarly, in the Late period, univariate analyses demonstrated that exposure to insulin was a potential confounder (Table 2). After adjustments for this factor, mean glucose values between the groups remained statistically different (p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Mean serum glucose concentrations in the Early period were similar in children with favorable (light grey bar) and unfavorable outcomes (dark grey bar)(133.3 ± 5.2 vs. 135.7 ± 7.3, respectively, p = 0.72) at 6 months. In the Late period, an association between elevated mean serum glucose concentrations and poor outcome was observed (133.5 ± 5.6 vs. 115.4 ± 4.1, p = 0.02, Figure 2). Neither relationship was altered after correction for multiple covariates.

Table 2.

Potential confounding variables between glucose and outcome when analyzed for mean concentrations in both time periods (Early – first 48 h; Late 49 – 168 h).

| EARLY PERIOD | Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | r value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.32 | ||

| Female | 139.8 ± 39.1 | ||

| Male | 131.0 ± 27.6 | ||

| Race | 0.41 | ||

| White | 132.8 ± 31.1 | ||

| Non-white | 142.7 ± 39.7 | ||

| Treatment | 0.14 | ||

| Hypothermia | 141.0 ± 39.2 | ||

| Normothermia | 128.1 ± 23.4 | ||

| Insulin | 0.07 | ||

| Yes | 143.4 ± 31.7 | ||

| No | 128.0 ± 31.8 | ||

| Age | 0.33 | 0.01 | |

| ISS | 0.25 | 0.07 | |

| GCS | 0.001 | 0.98 | |

| LATE PERIOD | Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | r value | p value |

| Gender | 0.92 | ||

| Female | 123.8 ± 32.9 | ||

| Male | 123.1 ± 22.9 | ||

| Race | 0.61 | ||

| White | 122.6 ± 27.9 | ||

| Non-white | 127.6 ± 20.2 | ||

| Treatment | 0.26 | ||

| Hypothermia | 127.5 ± 33.7 | ||

| Normothermia | 119.3 ± 17.3 | ||

| Insulin | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 135.7 ± 32.6 | ||

| No | 114.4 ± 17.0 | ||

| Age | 0.19 | 0.15 | |

| ISS | 0.21 | 0.12 | |

| GCS | −0.14 | 0.30 |

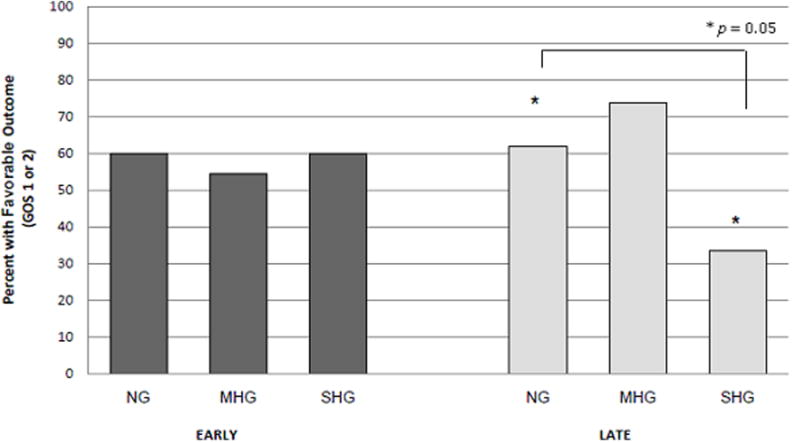

For Analysis 2, no association between outcome and peak serum concentrations in the Early period was observed (% favorable outcome: NG – 60%, MHG – 54.5%, SHG – 60%, p = 0.80, Figure 3). However, in the Late period, children within the SHG had decreased incidence of good outcome compared to children within the other glycemic groups (% good outcome: NG – 61.9%, MHG – 73.7%, SHG – 33.3%; p = 0.05, Figure 3). For Analysis 2, only exposure to insulin was significantly different between the glycemic groups during the Late period (p = 0.003, Table 3). None of the confounding variables differed among glycemic groups during the Early period (Table 3). After controlling for insulin use, the effects of MHG and SHG on outcome were no longer statistically significant when compared to NG (p = 0.323 and 0.272, respectively).

Figure 3.

No association between outcome and peak serum concentrations in the Early period (dark grey bars) was observed (% favorable outcome: NG – 60%, MHG – 54.5%, SHG – 60%, p = 0.80). In the Late period (light grey bars), children within the SHG had decreased incidence of good outcome compared to children within the other glycemic groups (% good outcome: NG – 61.9%, MHG – 73.7%, SHG – 33.3%; p = 0.05, *denotes statistical significance between the NG and SHG groups [p = 0.05]). After controlling for insulin use, the effects of MHG and SHG on outcome were relatively strong but not statistically significant compared to NG (p = 0.323 and 0.272, respectively).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of potential confounding variables between glucose and outcome (% with favorable outcome) when children were categorized into glycemic groups (Early – first 48 h; Late 49 – 168 h; normal (NG) – peak glucose < 150 mg/dl; mild hyperglycemia (MHG) – peak glucose ≤ 200 mg/dl; severe hyperglycemia (SHG) – peak glucose > 200 mg/dl).

| EARLY | NG | MHG | SHG | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=11 | n=11 | n=35 | ||

| Female (%) | 3.64 | 36.36 | 30.56 | 0.140 |

| White (%) | 90.91 | 100.00 | 77.78 | 0.165 |

| Hypothermia (%) | 27.27 | 63.64 | 50.00 | 0.220 |

| Age (mean months) | 76.37 | 99.90 | 77.30 | 0.158 |

| ISS (mean) | 22.10 | 27.45 | 25.71 | 0.151 |

| GCS (mean) | 6.27 | 5.82 | 6.14 | 0.748 |

| Insulin (%) | 18.18 | 36.36 | 48.57 | 0.296 |

| LATE | NG | MHG | SHG | p value |

| n=21 | n=19 | n=17 | ||

| Female (%) | 42.86 | 26.32 | 41.18 | 0.505 |

| White (%) | 85.71 | 89.47 | 76.47 | 0.550 |

| Hypothermia (%) | 42.86 | 42.11 | 64.71 | 0.308 |

| Age (mean months) | 66.84 | 87.85 | 95.52 | 0.232 |

| ISS (mean) | 24.71 | 26.38 | 26.19 | 0.660 |

| GCS (mean) | 6.52 | 5.94 | 5.71 | 0.201 |

| Insulin (%) | 14.29 | 47.37 | 68.75 | 0.003 |

Five children developed hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 50, 5/57, 8.6% incidence) and data regarding timing, blood glucose concentration and GOS are summarized in Table 4. Hypoglycemia was not associated with poor outcome or with exposure to insulin (p = 0.349 and 0.384, respectively, Fisher exact). For children with AHT (n = 10), mean serum glucose values in both Early and Late periods was not different than children who suffered accidental injury (127.7 ± 12.8 vs. 135.6 ± 4.5, p = 0.40; 125.8 ± 9.2 vs. 122.9 ± 3.9, p = 0.87, respectively). There was also no difference in peak serum glucose concentrations between AHT and children who suffered accidental injury in Early or Late periods (p = 0.66 and 0.62, respectively). Data regarding children who died is presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Demographic and outcomes of children who developed severe hypoglycemia (Early – first 48 h; Late 49 – 168 h).

| Age (mos) | Initial GCS | Early Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | Late Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | Lowest Blood Glucose (mg/dl) | Time when hypoglycemia was observed | Insulin Exposure During Study Period* | GOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91.4 | 4 | 178.4 | 113.0 | 48 | Early | Y | 5 |

| 159.2 | 7 | 120.1 | 103.6 | 28 | Late | N | 3 |

| 1.8 | 3 | 86.7 | 84.6 | 49 | Early | N | 1 |

| 40.7 | 6 | 121.9 | 109.7 | 39 | Late | Y | 1 |

| 47.7 | 3 | 106.4 | 158.8 | 42 | Early | Y | 3 |

Note: Timing of insulin exposure in relation to hypoglycemia could not be determined by our data collection system.

Table 5.

Demographics and glucose levels of children who died.

| Age (mos) | Initial GCS | Initial Glucose | Early Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | Early Group | Late Mean Glucose (mg/dl) | Late Group | Insulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.7 | 7 | 265 | 112.9 | SHG | 121.9 | NG | Y |

| 28 | 6 | 183 | 222.7 | SHG | 151.3 | SHG | Y |

| 91.4 | 4 | 357 | 178.5 | SHG | 113.1 | MHG | Y |

| 181.3 | 6 | 148 | 220.7 | SHG | 169.0 | SHG | Y |

| 164.9 | 4 | 111 | 113.3 | NG | 133.8 | SHG | Y |

Discussion

We have found that hyperglycemia beyond 48 hours after severe TBI in children is associated with poor outcome. This relationship was observed in our analysis of mean blood glucose concentrations and a trend was observed when episodic hyperglycemia was analyzed. This suggests a relationship between hyperglycemia and outcome from TBI. However, only a prospective study can answer the important question, whether manipulating serum glucose concentration can improve outcome after TBI in children.

Early Hyperglycemia after TBI

Serum glucose has long been studied as a marker that might have prognostic value early after TBI. Several retrospective studies have demonstrated that admission serum glucose concentrations were associated with adverse outcome (25-28, 33-34). Young and colleagues demonstrated an association between increases of admission glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl and poor outcome at 18 day, 3 month and 1 year follow up of 59 adults after TBI (25). Similarly, Lam and colleagues demonstrated an association between admission glucose and both outcome and initial GCS in 169 adults with severe TBI (33). Yang described an association between early hyperglycemia and poor outcome, but also linked increases of serum glucose to increased catecholamine concentrations and lower GCS score (26). In children, Cochran and colleagues found that fatal TBI was strongly associated with increased admission serum glucose concentrations (267 mg/dl vs. 135 mg/dl, p < 0.001)(10). We, however, were unable to confirm this association between early hyperglycemia and outcome using either mean or peak glucose concentrations. Multiple aspects of our patient population and care potentially could explain this observation. Because of the referral pattern within our region, more than 80% of our children are transported from other facilities prior to stabilization within our trauma system. Because pre-hospital information is not screened for inclusion within our database, we were unable to determine from our retrospective data whether the first glucose concentration recorded represented the admission concentration. In light of this fact and given our rigorous protocol for withholding exogenous glucose, we chose to separate our epochs into early (first 48 h) and late (49 h – 169 h).

Our early finding of no association with outcome is also in conflict with Young and colleagues observation that peak 24 h glucose concentrations are associated with outcome(25). Our analysis incorporated both mean glucose as well as peak concentrations in the early time period, and demonstrated no such association. In children, Marton demonstrated that hyperglycemia within the first 24 h of TBI in infants (< 12 months old) was highly correlative with poor outcome (12). To our knowledge, ours is the first study to evaluate this association with a strategy of limited or no glucose administration during the first 2 days after injury. While it is possible that our strategy for withholding glucose early is responsible for this lack of association between glucose and outcome early after TBI, further study of the optimal glucose management strategy in pediatric TBI is obviously needed.

Delayed Hyperglycemia after TBI

Contrasting our findings in the first 48 hours after TBI, delayed hyperglycemia was associated with poor outcome in children in our study. These findings are consistent with findings in adults (28). Jeremitsky and colleagues showed (i) an association between hyperglycemia on hospital day 3 and mortality and (ii) hyperglycemia on days 3 – 5 and unfavorable outcome in TBI patients (28). Salim and colleagues reported that persistent hyperglycemia (average daily serum glucose > 150 mg/dl) was independently associated with mortality with an OR of 4.91 [2.88 – 8.56](35) in a large series of TBI patients. In children, Chiaretti and colleagues demonstrated an association between hyperglycemia and outcome after TBI of a smaller magnitude (OR = 1.55 [1.01 – 2.33] (7).

Our findings suggest an association between hyperglycemia (both mean and peak concentrations) and outcome with unfavorable outcome after 48 hours which may have several potential clinical implications. First, in contrast to the initial 48 hours, we (and most other studies) have provided less rigorous control of glucose administration after 48 hours. It is possible that a more carefully titrated protocol of glucose (and overall nutrient) administration may lead to improvements in glycemic control and may yield decreases in mortality or morbidity. Van den Berghe and colleagues found that a protocol which achieved serum glucose concentrations within a narrow range (serum glucose ≤ 100 mg/dl) decreased mean and maximal intracranial pressure, decreased seizure frequency, decreased incidence of diabetes insipidus and improved long term functional outcome (29). However, when a similar paradigm of “tight glucose control” was performed by Vespa and colleagues in 14 adult TBI victims and compared with 33 subjects with more liberal glucose goals (serum glucose range of 120-150 mg/dl), those with intensive insulin therapy demonstrated evidence of cellular distress in brain (increases in microdialysis concentrations of glutamate, lactate/pyruvate ratio and increased oxygen extraction) without any outcome benefit (30). Thus, a specific glucose target in patients with TBI, including children, remains controversial. Our retrospective study was not designed to answer the important question of whether tight glucose control can improve the outcome of children after TBI. However, because of aforementioned concerns, it appears that a well-designed trial testing precise administration and control of glucose would be warranted for children with TBI to attempt to maximize neurological outcome while minimizing potentially important secondary injuries.

There are several limitations to our findings. First, despite a prospectively applied glucose regimen in the initial 48 hours and a rigorous treatment protocol for elevations of ICP, we did not use a standard protocol to control glucose or provide insulin after the first 48 hours. Second, despite efforts to collect precise temporal data regarding insulin administration and glucose values on all patients in this study, in this retrospective review we could only determine if exposure to insulin affected outcomes. Since the insulin use at our institution (and others) was rapidly evolving in the years 1999 – 2004, it is impossible for us to discern with certainty whether insulin use played an important role in the outcomes we found. Nevertheless, we believe that prospective trials should be undertaken in the future to answer this question more definitively and these trials should include standard glucose testing procedures discriminating point-of-care testing and other methodologies. Lastly, more than half of our patients were enrolled in studies of therapeutic hypothermia, of which 46% received the therapy. Since hypothermia is necessarily implemented early after TBI, it may have played some confounding effect either in the early period or during re-warming that could not be tested in our study design. We believe that ongoing multicenter studies of hypothermia may answer this question more definitively than this single center report.

In conclusion, we found that hyperglycemia beyond the initial 48 hours – measured as a daily average or during defined episodes – is associated with poor neurological outcome in children with severe TBI. Defining the optimal approach to glucose and nutrient management after severe TBI in children - including whether limiting glucose within the first 48 hours or treating observed hyperglycemia in children - merits additional prospective investigation focusing on real time multimodality monitoring aimed at metabolism and glucose utilization in the brain along with studies of long-term outcome.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Smith was supported for this work by a grant from NIH (T32 HD040686)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yates AR, Dyke PC, 2nd, Taeed R, et al. Hyperglycemia is a marker for poor outcome in the postoperative pediatric cardiac patient. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7(4):351–355. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000227755.96700.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirshberg E, Larsen G, Van Duker H. Alterations in glucose homeostasis in the pediatric intensive care unit: Hyperglycemia and glucose variability are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(4):361–366. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318172d401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yung M, Wilkins B, Norton L, et al. Glucose control, organ failure, and mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(2):147–152. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181668c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulate KP, Lima Falcao GC, Bielefeld MR, et al. Strict glycemic targets need not be so strict: a more permissive glycemic range for critically ill children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e898–904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preissig CM, Rigby MR, Maher KO. Glycemic control for postoperative pediatric cardiac patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30(8):1098–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein GW, Hojsak JM, Schmeidler J, et al. Hyperglycemia and outcome in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2008;153(3):379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiaretti A, Piastra M, Pulitano S, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of children with severe head injury: an 8-year experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18(3-4):129–136. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michaud LJ, Rivara FP, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Elevated initial blood glucose levels and poor outcome following severe brain injuries in children. J Trauma. 1991;31(10):1356–1362. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paret G, Tirosh R, Lotan D, et al. Early prediction of neurological outcome after falls in children: metabolic and clinical markers. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16(3):186–188. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochran A, Scaife ER, Hansen KW, et al. Hyperglycemia and outcomes from pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2003;55(6):1035–1038. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000031175.96507.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma D, Jelacic J, Chennuri R, et al. Incidence and risk factors for perioperative hyperglycemia in children with traumatic brain injury. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(1):81–89. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818a6f32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marton E, Mazzucco M, Nascimben E, et al. Severe head injury in early infancy: analysis of causes and possible predictive factors for outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23(8):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818990d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambiru S, Kato A, Kimura F, et al. Poor postoperative blood glucose control increases surgical site infections after surgery for hepato-biliary-pancreatic cancer: a prospective study in a high-volume institute in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(3):230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vriesendorp TM, Morelis QJ, Devries JH, et al. Early post-operative glucose levels are an independent risk factor for infection after peripheral vascular surgery. A retrospective study Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28(5):520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen TK, Thiel S, Wouters PJ, et al. Intensive insulin therapy exerts antiinflammatory effects in critically ill patients and counteracts the adverse effect of low mannose-binding lectin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(3):1082–1088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langouche L, Vanhorebeek I, Vlasselaers D, et al. Intensive insulin therapy protects the endothelium of critically ill patients. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2277–2286. doi: 10.1172/JCI25385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanhorebeek I, De Vos R, Mesotten D, et al. Protection of hepatocyte mitochondrial ultrastructure and function by strict blood glucose control with insulin in critically ill patients. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):53–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17665-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundgren J, Smith ML, Siesjo BK. Influence of moderate hypothermia on ischemic brain damage incurred under hyperglycemic conditions. Exp Brain Res. 1991;84(1):91–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00231764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis LM, Pauly JR, Readnower RD, et al. Fasting is neuroprotective following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(8):1812–1822. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verweij BH, Muizelaar JP, Vinas FC, et al. Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(5):815–820. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergsneider M, Hovda DA, Shalmon E, et al. Cerebral hyperglycolysis following severe traumatic brain injury in humans: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosurg. 1997;86(2):241–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.2.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hovda DA, Lee SM, Smith ML, et al. The neurochemical and metabolic cascade following brain injury: moving from animal models to man. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12(5):903–906. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashwal S, Holshouser BA, Shu SK, et al. Predictive value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in pediatric closed head injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23(2):114–125. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young B, Ott L, Dempsey R, et al. Relationship between admission hyperglycemia and neurologic outcome of severely brain-injured patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210(4):466–472. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00007. discussion 472-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang SY, Zhang S, Wang ML. Clinical significance of admission hyperglycemia and factors related to it in patients with acute severe head injury. Surg Neurol. 1995;44(4):373–377. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(96)80243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rovlias A, Kotsou S. The influence of hyperglycemia on neurological outcome in patients with severe head injury. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(2):335–342. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200002000-00015. discussion 342-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeremitsky E, Omert LA, Dunham CM, et al. The impact of hyperglycemia on patients with severe brain injury. J Trauma. 2005;58(1):47–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000135158.42242.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Berghe G, Schoonheydt K, Becx P, et al. Insulin therapy protects the central and peripheral nervous system of intensive care patients. Neurology. 2005;64(8):1348–1353. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158442.08857.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vespa P, Boonyaputthikul R, McArthur DL, et al. Intensive insulin therapy reduces microdialysis glucose values without altering glucose utilization or improving the lactate/pyruvate ratio after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):850–856. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201875.12245.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parish RA, Webb KS. Hyperglycemia is not a poor prognostic sign in head-injured children. J Trauma. 1988;28(4):517–519. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198804000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adelson PD, Ragheb J, Kanev P, et al. Phase II clinical trial of moderate hypothermia after severe traumatic brain injury in children. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(4):740–754. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156471.50726.26. discussion 740-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam AM, Winn HR, Cullen BF, et al. Hyperglycemia and neurological outcome in patients with head injury. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(4):545–551. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.4.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walia S, Sutcliffe AJ. The relationship between blood glucose, mean arterial pressure and outcome after severe head injury: an observational study. Injury. 2002;33(4):339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salim A, Hadjizacharia P, Dubose J, et al. Persistent hyperglycemia in severe traumatic brain injury: an independent predictor of outcome. Am Surg. 2009;75(1):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]