Transcription factor NF-κB and its activating kinase IKKβ are associated with inflammation and believed to be critical for innate immunity. Despite likelihood of immune suppression, pharmacological blockade of IKKβ–NF-κB has been considered as a therapeutic strategy. However, we found neutrophilia was seen in mice with inducible deletion of Ikkβ (IkkβΔ mice). These mice had hyperproliferative granulocyte-macrophage progenitors and pregranulocytes and a prolonged lifespan of mature neutrophils that correlated with the induction of genes encoding prosurvival molecules. Deletion of interleukin 1 receptor 1 (IL-1R1) in IkkβΔ mice normalized blood cellularity and prevented neutrophil-driven inflammation. However, IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice, unlike IkkβΔ mice, were highly susceptible to bacterial infection, which indicated that signaling via IKKβ–NF-κB or IL-1R can maintain antimicrobial defenses in each other’s absence, whereas inactivation of both pathways severely compromises innate immunity.

Neutrophils are phagocytic cells that provide a critical first line of innate immune defense against bacterial and fungal infection1. Nonactivated neutrophils circulate in the blood with an average half-life of 6–7 h (ref. 2). Peripheral neutrophil counts are tightly maintained by ‘steady-state’ granulopoiesis, but acute infection or inflammation trigger the rapid mobilization of neutrophil stores and accelerate bone marrow granulopoiesis3,4. Circulating neutrophils are then activated and migrate toward the lesion, where they kill microbes through phagocytosis, the release of soluble antimicrobials and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps1,5,6. During microbial killing, neutrophils undergo accelerated apoptosis due to oxidative stress caused by intracellular H2O2 production7. Neutrophils also have a major role in wound healing, and overexuberant neutrophil responses contribute to pathologic, often destructive, inflammatory processes8. Like other blood cells, neutrophils originate from self-renewing long-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)4,9,10. By asymmetric division, these cells give rise to short-term hematopoietic stem cells that have limited self-renewal capacity and give rise to multipotent progenitors (MPPs)9–11. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor (CMP) produced by multipotent progenitors gives rise to progenitors restricted to either the megakaryocyte-erythrocyte (MEP) or granulocyte-macrophage (GMP) lineage10. The proliferation of such progenitors is controlled by several hematopoietic growth factors, including G-CSF, M-CSF, GM-CSF, interleukin 3 (IL-3), IL-6 and SCF12.

A key role in inflammation is served by the transcription factor NF-κB (A001645); this has given rise to the idea that inhibitors of activation of NF-κB can be used for the prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory conditons13. NF-κB is also upregulated in cancer, in which it is responsible for inhibition of cell death and expression of tumor promoting cytokines14. However, activation of NF-κB is also known to be critical for innate and adaptive immunity15,16. Activation of NF-κB depends on the inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) complex, especially its Ikkβ catalytic subunit (A001172)17. Despite the potential risk of inducing immunodeficiency, much effort has been placed on the development of Ikkβ inhibitors as potential anti-inflammatory or anticancer drugs18,19. It was therefore unexpected that such inhibitors (for example, ML120B20) were found to increase inflammation in mice21. Similar observations have been obtained with mice in which Ikkβ is deleted in myeloid cells or mice are subjected to prolonged treatment with another Ikkβ inhibitor21,22, but the molecular mechanism of spontaneous neutrophilia in the absence of IKKβ–NF-κB has remained unknown. Here we have investigated the basis of this neutrophilia and found it was dependent on IL-1β (A003663), which acted as a growth factor for neutrophil progenitors and as a survival factor for mature neutrophils. Although inhibition of IL-1 signaling prevented neutrophilia and restored neutrophil homeostasis, it rendered IKKβ-deficient mice highly susceptible to bacterial infection, which suggests that enhanced IL-1β production represents a compensatory mechanism for maintaining antibacterial defense when NF-κB is inhibited.

RESULTS

Severe neutrophilia and inflammation after IKKβ deletion

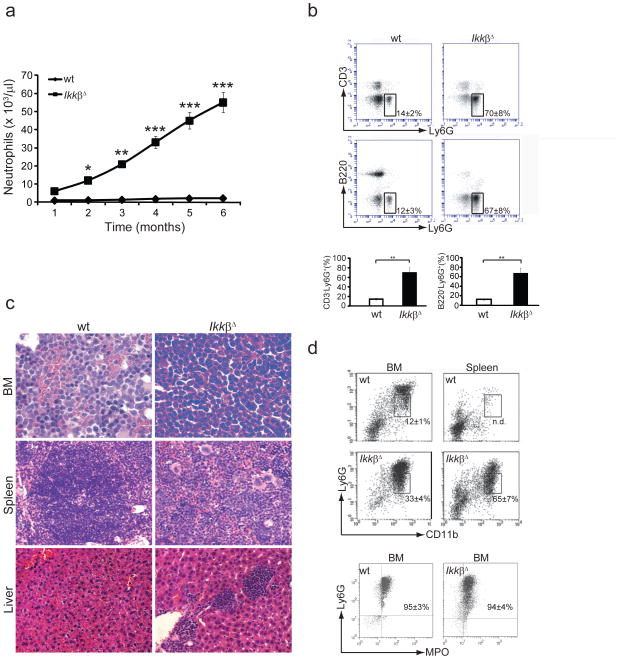

We deleted the gene encoding Ikkβ (Ikbkb) in cells responsive to type I interferon by administering polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) to mice with conditional deletion of loxP-flanked Ikbkb alleles by Cre recombinase expressed from the Mx1 promoter23 (called ‘IkkβΔ mice’ here). Ikbkb deletion occurred in cells of the myeloid lineage, causing greater neutrophilia in the absence of any overt stimulus than in mice with loxP-flanked Ikbkb alleles without Cre-mediated deletion (called ‘wild-type mice’ here)21,24(Fig. 1a). Neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice occurred as early as 2 weeks after poly(I:C) administration and progressed rapidly (Fig. 1a). Peripheral neutrophil counts increased up to 6 ×104 cells per μl by 6 months after poly(I:C) injection. The expanded neutrophils were Ly6G+ (Fig. 1b) and seemed mature, with normal shape and segmentation (Supplementary Fig. 1a). IkkβΔ mice also had more circulating eosinophils, monocytes and platelets (Supplementary Fig. 1b), whereas B cell and T cell counts remained within the normal range (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Most IkkβΔ mice died approximately 6 months after poly(I:C) administration, apparently succumbing to overwhelming generalized inflammation. Examination of mice killed 2 months after poly(I:C) injection showed that the bone marrow of IkkβΔ mice was packed with neutrophils and neutrophil progenitors (Fig. 1c). IkkβΔ mice also had massive neutrophil infiltrates in spleen and liver (Fig. 1c) and considerable splenomegaly. Flow cytometry showed a higher percentage of CD11b+Ly6Glo immature neutrophils25 than CD11b+Ly6G+ mature neutrophils, not only in bone marrow, but also in spleens of IkkβΔ mice relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 1d). Most of these cells also expressed the neutrophil marker myeloperoxidase25 (Fig. 1d). These results suggested substantial extramedullar production of neutrophils in IkkβΔ mice.

Figure 1.

IkkβΔ mice develop neutrophilia. (a) Neutrophil counts in the blood of wild-type (wt) and IkkβΔ mice collected retro-orbitally at various time points (horizontal axis) after injection of poly(I:C). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.02 and ***P < 0.01 (Student’s t test) Data were obtained from 12 mice per genotype (average ± s.d.). (b) Flow cytometry of peripheral blood cells collected from wild-type and IkkβΔ mice and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated antibody to CD3 (anti-CD3) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Ly6G (top) or with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-B220 and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Ly6G (middle). Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent (± s.d.) CD3−Ly6G+ cells (top) or B220−Ly6G+ cells (middle). Below, quantification of the results above. *P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). Data are representative of 2 experiments with three separate measurements per genotype (error bars, s.d.). (c) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained wild-type and IkkβΔ bone marrow (BM), spleen and liver sections. Original magnification, ×40 (spleen and liver) or ×100 (bone marrow). Data are representative of 2 experiments with three mice per genotype. (d) Flow cytometry of wild-type and IkkβΔ bone marrow and spleen cells stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Ly6G and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-CD11b, assessing gated Ly6GloCD11b+ immature granulocytes (top). Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate the frequency of Ly6GloCD11b+ cells relative to total Ly6G+CD11b+ cells (± s.d.). Below, flow cytometry of bone marrow cells stained with anti-Ly6G and intracellular anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO). Numbers in plots indicate percent Ly6G+MPO+ cells (± s.d.). Data are representative of three experiments.

Neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice is transplantable

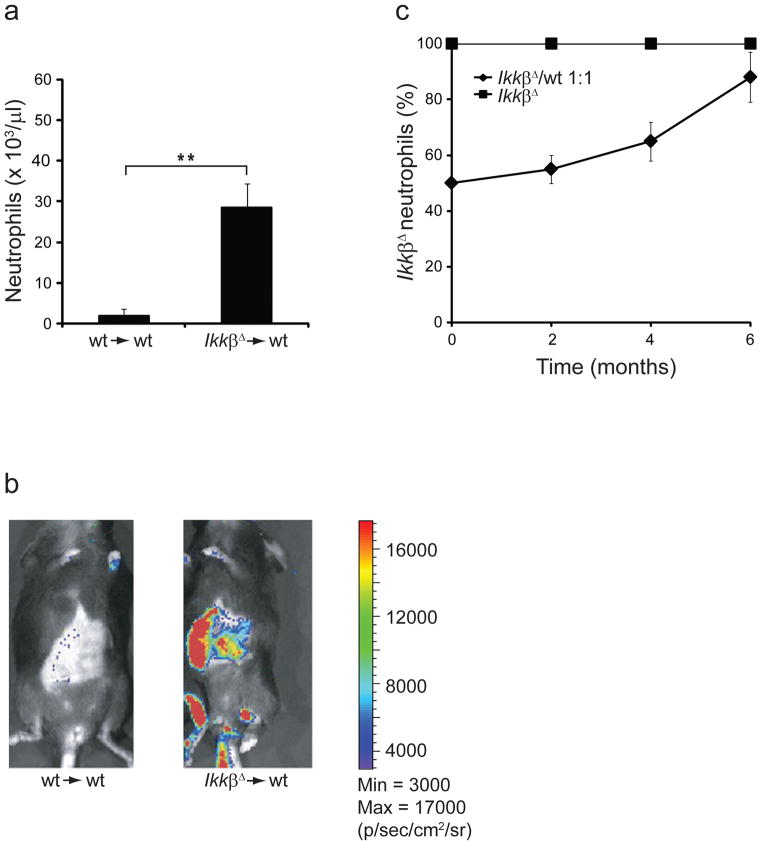

To determine whether the neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice was transplantable, we injected IkkβΔ and wild-type bone marrow into lethally irradiated wild-type mice and counted peripheral neutrophils 3 months later. We also did reciprocal transplantation by injecting wild-type bone marrow into lethally irradiated IkkβΔ mice (n = 3; data not shown). The neutrophil counts of wild-type mice reconstituted with IkkβΔ bone marrow cells were very high, but those of mice that received wild-type bone marrow cells and of IkkβΔ mice that received wild-type bone marrow cells remained in the normal range (Fig. 2a and data not shown). To monitor the fate of transplanted cells in wild-type recipients, we transduced IkkβΔ and wild-type bone marrow cells with a luciferase reporter before transplantation. Bioluminescence-based imaging at 30 d after bone marrow transfer showed that luciferase-expressing cells from IkkβΔ donors had accumulated mainly in the spleen, liver and long bones of wild-type recipients (Fig. 2b), the same organs that had higher neutrophil counts in IkkβΔ mice. We detected almost no signal in mice transplanted with wild-type bone marrow cells, which suggested that IkkβΔ bone marrow cells had a much greater proliferative capacity than wild-type bone marrow cells had. To confirm that observation, we transplanted a 1:1 mixture of CD45.1+ C57BL/6 wild-type bone marrow and IkkβΔ CD45.2+ bone marrow into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ C57BL/6 wild-type mice. This experiment confirmed that IkkβΔ bone marrow cell populations expanded much faster than wild-type bone marrow cells did (Fig. 2c). We also observed a slightly more IkkβΔB cells and T cells (nonsignificant difference; Supplementary Fig. 2a, b), as well as substantially more eosinophils, monocytes and platelets (data not shown). Together our experiments showed that neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice was transplantable and that the neutrophilia was driven solely by factors intrinsic to hematopoietic cells, causing accelerated proliferation and/or enhanced survival of neutrophil progenitors or mature neutrophils.

Figure 2.

Neutrophilia in IKKβ-deficient mice is transplantable. (a) Neutrophil counts in the peripheral blood of lethally irradiated wild-type mice 3 months after transplantation with wild-type (wt→wt) or IkkβΔ (IkkβΔ→wt) bone marrow cells. *P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). Data were collected from six mice per genotype (error bars, s.d.). (b) Bioluminescence-based imaging of irradiated wild-type mice 30 d after adoptive transfer of wild-type or IkkβΔ bone marrow cells transduced with a luciferase reporter. Heat map at left indicates bioluminescence in photons per second per cm2 per steradian (p/s/cm2/sr): minimum, 3 × 103; maximum, 17 × 103. Data are representative of three experiments per group. (c) Peripheral IkkβΔ neutrophils in lethally irradiated CD45.1+ C57BL/6 wild-type mice given transplantation of 5 × 106 bone marrow cells from CD45.2+ IkkβΔ mice plus 5 × 106 bone marrow cells from CD45.1+ C57BL/6 wild-type mice, or 1 × 107 CD45.2+ IkkβΔ bone marrow cells alone (positive control); results were calculated on the basis of differential blood counts and on flow cytometry with labeled anti-CD45.1 (wild-type cells) or anti-CD45.2 (IkkβΔ cells) and anti-Ly6G. Data were collected from three mice per group (mean ± s.d.).

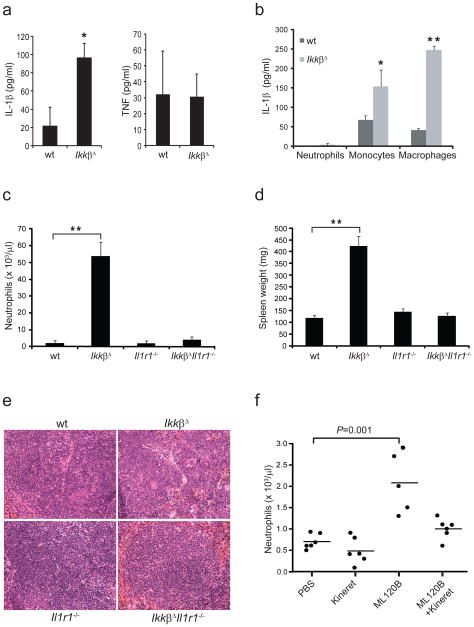

IL-1β signaling is responsible for neutrophilia

IkkβΔ mice produce more IL-1β than wild-type mice after challenge with lipopolysaccharide or bacterial infection21. Here we found that even without any exogenous stimulus, IkkβΔ mice produced more circulating IL-1β than did age-matched wild-type mice, whereas circulating tumor necrosis factor did not differ in the two groups (Fig. 3a). Isolated IkkβΔ monocytes and macrophages secreted considerable amounts of IL-1β even without stimulation, but neutrophils did not (Fig. 3b). This finding is in line with published observations describing monocytes and macrophages as the main sources of IL-1β26. Notably, IkkβΔ mice also deficient in IL-1 receptor 1 (IL-1R1; IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice) maintained almost normal neutrophil counts and did not develop splenomegaly or neutrophilic organ infiltration (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Eosinophil, monocyte, and platelet counts were also normal in IkkβΔIl1r1−/− double mutants (data not shown). IkkβΔ mice rendered deficient in caspase-1 (IkkβΔCasp1−/− mice) still had higher neutrophil counts, but these counts were nowhere near the magnitude in IkkβΔ mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Whereas IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice maintained much higher serum concentrations of IL-1β (Supplementary Fig. 4b), IkkβΔCasp1−/− mice had lower circulating IL-1β (Supplementary Fig. 4c), which supported published findings showing that caspase-1 is involved in macrophage- and monocyte-derived production of IL-1β in IkkβΔ mice21. Nonetheless, circulating concentrations of IL-1β were higher in IkkβΔ Casp1−/− mice than in wild-type mice, which indicated that some of the IL-1β in IkkβΔ mice was derived from a caspase-1-independent source. Histological analysis of IkkβΔ Il1r1−/− spleens showed a nearly complete reversal of the disrupted splenic architecture caused by massive neutrophil infiltration and extramedullar hematopoiesis in IkkβΔ mice (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 5). Pharmacological mimicry of the Ikkβ deficiency via treatment of wild-type mice with the Ikkβ inhibitor ML120B20 also led to much higher neutrophil counts within 8 d of treatment (Fig. 3f). This neutrophilia was preventable by the combination of ML120B and the IL-1R antagonist anakinra. Together these results indicate that excessive IL-1β signaling is responsible for uncontrolled neutrophilia and inflammation in IKKβ-deficient mice.

Figure 3.

Ablation of IL-1R1 prevents neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice. (a) Serum concentrations of IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in wild-type and IkkβΔ mice 6 months after injection of poly(I:C). (b) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of IL-1β in supernatants of neutrophils (Neut), monocytes (Mono) and macrophages (Mac) from wild-type and IkkβΔ mice given intraperitoneal injection of thioglycollate, followed by collection of peritoneal and peripheral blood cells, purification with magnetic beads and culture for 24 h at a density of 1 × 105 cells per 100 μl. (c) Peripheral neutrophil counts in mice of various genotypes (horizontal axis) 6 months after injection of poly(I:C). (d) Spleen weights 2 months after injection of poly(I:C) collected from 3 mice per genotype. (e) Hematoxyiln and eosin–stained spleen sections from mice in d. Original magnification, ×40. (f) Peripheral neutrophil counts of wild-type mice treated with PBS, anakinra or ML120B alone or anakinra plus ML120B. Each symbol represents an individual count; small horizontal bars indicate the median. (Student’s t test). Data are representative of 2 (a), 2 (b), or 2 (c), experiments with three mice per genotype (mean and s.d. in a–d) or 2 experiments with six mice per group (f).

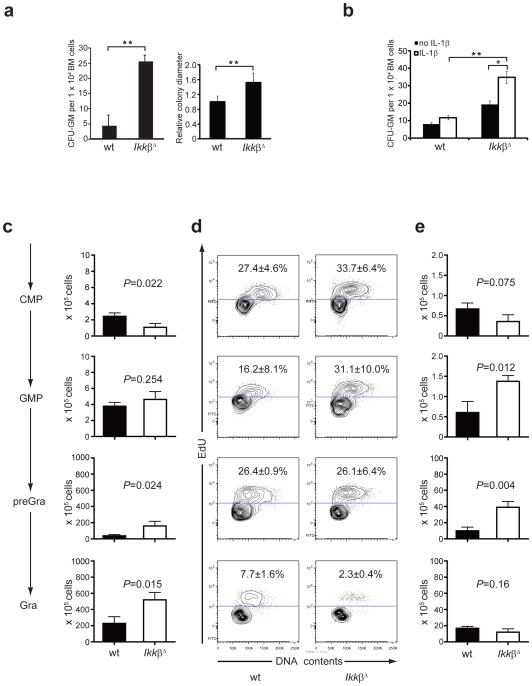

Hyperproliferation of IkkβΔ granulocyte progenitors

We examined whether the neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice was due to enhanced proliferation of granulocyte progenitors. We plated equal numbers of wild-type, IkkβΔ, Il1r1−/− and IkkβΔIl1r1−/− bone marrow cells in stem cell medium and analyzed colonies 10 d later. IkkβΔ bone marrow cells gave rise to many more and larger granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GM) than did wild-type bone marrow cells (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6) and IL-1R1 deletion in the context of Ikkβ deficiency restored CFU-GM numbers to the normal range (IkkβΔIl1r1−/− bone marrow mean colony number: 5±3, data not shown). Absence of IL-1R1 signaling also normalized colony sizes (data not shown). Microscopic examination of colonies from IkkβΔ bone marrow and wild-type bone marrow cells showed that the majority of the cells were neutrophilic granulocytes or their progenitors (Supplementary Fig. 6). To determine whether exogenous IL-1β was sufficient to enhance CFU-GM, we incubated wild-type and IkkβΔ bone marrow cells with or without recombinant IL-1β. Although recombinant IL-1β had only a small effect on the CFU-GM of wild-type bone marrow cells, it resulted in considerably enhanced CFU-GM of IkkβΔ bone marrow cells (Fig. 4b). These results are consistent with the results of the bone marrow–mixture experiments described above and indicate a cell-intrinsic defect that enhances IL-1β responsiveness in the absence of IKKβ. To pinpoint the progenitor cell type that gives rise to more neutrophils in IkkβΔ mice, we determined the frequency of CMPs, GMPs, pre-granulocytes and granulocytes by flow cytometry assessing size and cell-cycle status10. We found that IkkβΔ bone marrow had a slightly smaller CMP population than did wild-type bone marrow, which could have reflected a negative feedback mechanism driven by the much larger pre-granulocyte or granulocyte population in IkkβΔ bone marrow (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the GMP population was not very different in bone marrow of the two genotypes. We next checked the proliferation status of the various progenitor cell populations by injecting mice with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) 3 h before collecting bone marrow. The incorporation of EdU was much greater in the GMP population, but not in the CMP, pre-granulocyte or granulocyte population, of IkkβΔ bone marrow than that of wild-type bone marrow (Fig. 4d). However, when we compared the number of cells in the S-G2-M portion of the cell cycle, we found significantly more cycling GMPs and pre-granulocytes in IkkβΔ bone marrow than in wild-type bone marrow (Fig. 4e). These results suggest that at least some of the neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice is due to enhanced proliferation of GMPs and pre-granulocyte progenitors.

Figure 4.

Larger granulocyte progenitor populations in IkkβΔ mice. (a) Colony counts (left) and diameters (right; y- axis is relative colony diameters compared to wild-type (wild-type mean is 1).) of wild-type and IkkβΔ bone marrow cells grown for 10 d in Methocult progenitor cell medium at a density of 3.3 × 103 cells per ml. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). Data are representative of 3 experiments with three plates per mouse and three mice per genotype (left) or 27 colonies per genotype (right; mean and s.d.). (b) Colony counts of wild-type and IkkβΔ bone marrow cells cultured as in a with or without recombinant IL-1β (100 ng/ml). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). Data are representative of 2 experiments (mean ± s.d.). (c) Sizes of CMP, GMP, pre-granulocyte (pre-Gra) and granulocyte (Gra) populations from the bone marrow of wild-type and IkkβΔ mice, assessed by flow cytometry and presented as absolute number per bilateral hind limb. Data are representative of 2 experiments with three mice per genotype (mean and s.d.). (d) Incorporation of EdU and DNA content of progenitor cell populations from the bone marrow collected from mice 3 h after injection of EdU (200 μg). Numbers in plots indicate percent EdU+ cells (mean ± s.d.). Data are from one representative of three independent experiments. (e) Actual number of cells in the S+G2+M portion of the cell cycle in d. P values, Student’s t test. Data are one representative of three independent experiments (error bars, s.d.).

Longer lifespan of IKKβ-deficient neutrophils

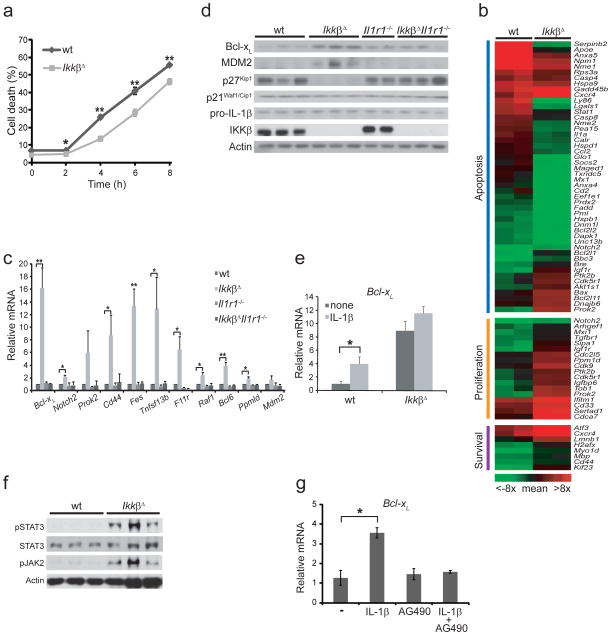

Another factor that could have contributed to the neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice was a longer neutrophil lifespan. To examine this possibility, we purified thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal neutrophils from wild-type and IkkβΔ mice with anti-Ly6G magnetic beads and cultured the cells. We stained the cells with propidium iodide at various time points and assessed by flow cytometry the frequency of propidium iodide–positive cells, considered nonviable. Wild-type neutrophils died faster than IkkβΔ neutrophils did (Fig. 5a). Of note, neutrophil proliferation was negligible during this period of observation (Supplementary Fig. 7). Similarly, we observed that purified IkkβΔ Ly6G+ peripheral blood neutrophils had a longer lifespan than their wild-type counterparts did (data not shown). Microarray analysis of thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal neutrophils identified several genes involved in cell proliferation and survival that were upregulated in IkkβΔ neutrophils relative to their expression in wild-type neutrophils (Fig. 5b). One such gene was Cd33, which encodes a sialoadhesin family member thought to be associated with the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells27. Conversely, proapoptotic genes were downregulated in IkkβΔ neutrophils and antiapoptotic genes were upregulated. We confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis the microarray data for key genes shown to be involved in hematopoiesis; this also included Il1r1−/− and IkkβΔIl1r1−/− neutrophils (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 8). Unexpectedly, genes typically activated by NF-κB in other cell types, such as those encoding the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL (refs. 28,29) and B cell–activation factor BAFF30, were upregulated in IkkβΔ neutrophils. We confirmed by immunoblot analysis higher expression of Bcl-xL in IkkβΔ neutrophils (Fig. 5d). Immunoblot analysis also showed that the cell cycle inhibitor p27 (ref. 31) was downregulated in IkkβΔ neutrophils. Expression of Bcl-xL mRNA was induced by IL-1β in wild-type neutrophils, but there was little Bcl-xL induction in neutrophils from IkkβΔ mice because they had higher basal Bcl-xL expression (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5.

Effects of Ikkβ ablation on neutrophil lifespan and gene expression. (a) Flow cytometry of cultured Ly6G+ peritoneal neutrophils stained with propidium iodide. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, compared with wild-type (Student’s t test).(b) Microarray analysis of gene expression in neutrophils isolated as in a; genes are grouped as encoding molecules relevant for apoptosis, proliferation or survival, and survival (one mouse per ‘lane’): red indicates genes with an intensity greater than the mean intensity of the genes presented here; green indicates genes with an intensity lower than that mean intensity. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression in peritoneal neutrophils. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).(d) Immunoblot analysis of proteins involved in cell survival and proliferation in lysates of peritoneal Ly6G+ neutrophils (genotype, above blot). (e) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Bcl-xL mRNA expression among total RNA from wild-type or IkkβΔ Ly6G+ peritoneal neutrophils incubated for 4 h with or without recombinant IL-1β (100 ng/ml), presented relative to. *P < 0.05 relative to none treatment. (Student’s t test). (f) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated (p-) STAT3 and Jak2 in lysates of wild-type or IkkβΔ Ly6G+ peritoneal neutrophils. (g) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Bcl-xL mRNA expression in wild-type Ly6G+ peritoneal neutrophils incubated for 4 h in the presence or absence of AG490 (30 μM) or recombinant IL-1β (100 ng/ml). *P < 0.05 relative to none treatment (Student’s t test). Data are representative of two (e, g) or three (a, c) independent experiments done in triplicate (error bars, s.d.). Each lane represents samples isolated from an indidual mouse (b, d, f).

STAT3 is another transcription factor that controls Bcl-xL expression32; STAT3 activity is enhanced in IKKβ-deficient hepatocytes33. Phosphorylation of STAT3 and its activating kinase Jak2 was enhanced in IkkβΔ neutrophils (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, inhibition of Jak2 activity suppressed the IL-1β-mediated induction of Bcl-xL in mature neutrophils (Fig. 5g). These data suggest that the higher Bcl-xL expression in IKKβ-deficient neutrophils was due to activation of Jak2 and STAT3. Together these results show that the absence of Ikkβ renders neutrophils and their progenitors more susceptible to the prosurvival and pro-proliferative effects of IL-1β.

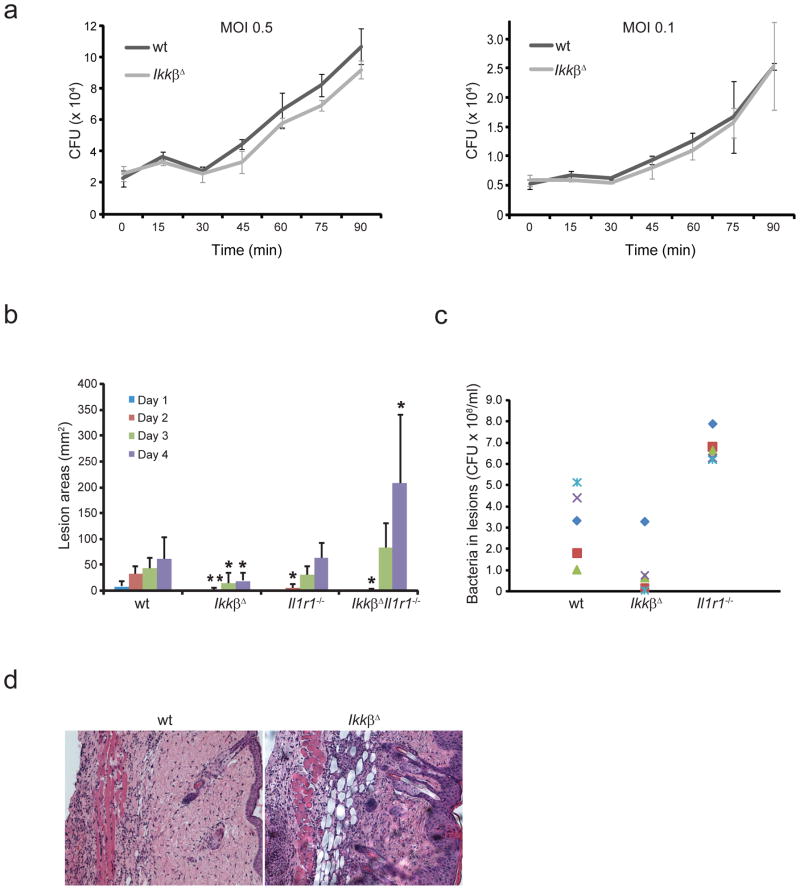

IKKβ-deficient neutrophils retain bactericidal activity

We determined whether IkkβΔ neutrophils retained normal bactericidal activity. We isolated peritoneal neutrophils after thioglycollate injection and assessed their ability to kill the bacterial pathogen group A Streptococcus (GAS). Unexpectedly, we observed no significant difference between wild-type and IkkβΔ neutrophils in their bacterial killing (Fig. 6a). We also injected GAS subcutaneously into wild-type, IkkβΔ, Il1r1−/− and IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice and monitored the development of necrotic skin lesions. Unexpectedly, IkkβΔ mice developed the smallest lesions with the fewest surviving bacteria, whereas IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice had the largest lesions (Fig. 6b, c and Supplementary Fig. 9). Whereas containment of the infectious challenge was better in IkkβΔ mice, probably reflective of the greater neutrophilic infiltration in the infected skin area (Fig. 6d), host defense was severely compromised in IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice (Fig. 6b). In contrast to IkkβΔ and Il1r1−/− mice, none of the IkkβΔIl1r1−/− mice survived longer than 4 d after infection (data not shown). Moreover, neutrophils from IkkβΔIl1r1−/− and Il1r1−/− mice showed impaired bactericidal function in vitro compared with that of wild-type neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 10). In summary, IKKβ-activated NF-κB was not critical for maintenance of antibacterial immunity, as its absence was compensated for by elevated IL-1β signaling. Reciprocally, IL-1β signaling is not essential for bacterial containment in IKKβ–NF-κB-competent mice.

Figure 6.

Inactivation of signaling via IL-1–IL-1R1 and IKKβ–NF-κB compromises antimicrobial immunity. (a) Killing of bacteria by peritoneal neutrophils collected from wild-type and IkkβΔ mice 4 h after thioglycollate injection, then incubated with GAS at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 or 0.1; results are presented as colony-forming units (CFU) of live bacteria. Data are representative of three independent experiments done in triplicate (mean ± s.d.). (b) Lesion size in mice given subcutaneous (back) injection of 1 × 108 GAS. (c) Live bacteria in lesions of mice in b that remained alive 4 d after infection. Each symbol indicates an individual mouse. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of skin lesions collected from the mice in b 4 d after infection. Original magnification, ×10. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, compared with wild-type (Student’s t test).

DISCUSSION

Being activated by most if not all pattern-recognition receptors, IKKβ-dependent NF-κB signaling is considered the key regulator of innate immune responses15,16. Thus, the main undesired side effect of inhibition of IKKβ–NF-κB as a therapeutic strategy was expected to be greater susceptibility to infections19. Unexpectedly, however, we found that mice in which Ikkβ was deleted from cells of the myeloid cell lineage as well as in other interferon-responsive cells (IkkβΔ mice) were no less able to fight GAS infection than were control wild-type mice. In contrast, IkkβΔ mice showed greater GAS clearance than that of their wild-type counterparts, most probably due to their much greater neutrophil count, driven by the enhanced IL-1β production that accompanies inhibition of IKKβ–NF-κB21,34,35. Inhibition of IL-1R1 signaling rendered IkkβΔ mice immunocompromised and unable to control GAS infection but did not compromise anti-GAS immunity in IKKβ–NF-κB–competent mice. These findings support the published hypothesis that signaling via IKKβ–NF-κB and IL-1β–IL-1R1 provides alternative pathways toward the activation of antibacterial defenses and that upregulation of IL-1β in response to IKKβ–NF-κB deficiency provides a safety net that compensates for loss of NF-κB-dependent antibacterial immunity21. However, the upregulation of IL-1β production in IKKβ–NF-κB-deficient mice ultimately comes at a price: severe and destructive inflammation due to sustained massive neutrophilia.

Neutrophilia caused by inhibition of NF-κB has been seen in lethally irradiated mice reconstituted with fetal liver cells from mice deficient in the NF-kB subunit RelA34,35 and Ikbkb−/− mice36 and in mice treated with various Ikkβ inhibitors20,22. However, until now, the exact cause of the neutrophilia triggered by IKKβ–NF-κB inhibition and ways to prevent it have not been identified, to our knowledge. Our results have indicated that the spontaneous neutrophilia is caused by a combination of two factors. First, suppression of the basal IKKβ–NF-κB activity in myeloid cells without any stimulation induces production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Second, inhibition of NF-κB in neutrophils and their progenitors results in the upregulation of signaling pathways (Jak2-STAT3) and genes important for cell proliferation and survival and the downregulation of proapoptotic and antiproliferative genes. These changes render IKKβ–NF-κB–deficient neutrophils and their progenitors responsive to the pro-proliferative and prosurvival effects of IL-1β. That conclusion was supported by the mixed–bone marrow transplantation experiment and the in vitro incubation of IkkβΔ and wild-type bone marrow cells with IL-1β. Despite being exposed to the same higher IL-1β concentrations, the IKKβ-expressing neutrophil population did not expand nearly as much as the IKKβ-deficient population did. Although IL-1β alone is unlikely to be the only cause of severe neutrophilia, its inhibition or ablation of its receptor completely prevented neutrophilia and the resulting destructive inflammatory condition in IkkβΔ mice.

The ability of IL-1β to stimulate the proliferation of neutrophil progenitors is consistent with a published report showing that IL-1β (called hemopoietin-1 at that time) acts synergistically with IL-3 to increase the number of colonies formed by primitive hematopoietic progenitors37. Subsequently, IL-1R1 signaling has been found to be essential for the proliferation of granulocyte progenitor cells in response to stimuli such as aluminum hydroxide38. Our findings suggest that the progenitor cell population mostly responsive to IL-1β, at least in IkkβΔ mice, is not the CMP population, which gives rise to all myeloid cells10, but is instead the GMP and pre-granulocyte populations. The slightly lower number of proliferative cycling CMPs in IkkβΔ mice could suggest the presence of a negative feedback mechanism, given the extremely high neutrophil count in these mice. Enhanced proliferation of the GMP population can explain why monocytes and eosinophils are also more abundant in IkkβΔ mice10.

Mature IkkβΔ neutrophils had a longer lifespan in vitro than did wild-type neutrophils, even without incubation with IL-1β. Unexpectedly, Ikkβ deficiency resulted in upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL, whose expression is transcriptionally stimulated by NF-κB in other cell types39. The basis for the upregulation of Bcl-xL in IKKβ-deficient neutrophils seemed to be their much greater Jak2-dependent STAT3 activity, found before to occur in response to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in IKKβ-deficient hepatocytes33. In contrast to antiapoptotic genes, proapoptotic genes were downregulated in IkkβΔ neutrophils, including the gene encoding PML, a known regulator of neutrophil apoptosis40. Given the profound effect of Ikkβ deletion in neutrophils and their progenitors on genes that control cell proliferation and survival, we speculate that the Ikkβ signaling pathway may be inactivated in malignancies derived from GMP and their progeny, such as blast-crisis chronic myeloid leukemia41.

Although our results indicate that inhibition of IL-1β signaling can be used to prevent the destructive neutrophilia associated with prolonged inhibition of IKKβ–NF-κB, this is an impractical solution for use in the clinic, as combined loss of signaling via IKKβ–NF-κB and IL-1β–IL-1R1 results in severe impairment of antibacterial defenses. These findings are consistent with the clinical observation that treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor, a strong activator and effector of IKKβ–NF-κB signaling, together with anakinra greatly enhances the risk of infection42. However, partial or temporary inhibition of IKKβ–NF-κB signaling, which is unlikely to trigger massive neutrophilia, could still find utility in the treatment of cancers in which NF-κB is persistently activated.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

Casp1−/− mice, mice with loxP-flanked Ikbkb alleles (wild-type), and mice with deletion of loxP-flanked Ikbk alleles by Cre recombinase expressed from the Mx1 promoter have been described21,24,43. For deletion of Ikbkb in those mice, 200 μg poly(I:C) (Amersham Biosciences) was injected intraperitoneally into 3- to 4-week-old mice three times every other day. Il1r1−/− and CD45.1+ wild-type mice were from the Jackson Laboratory. All mouse strains were crossed for at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6 background and were housed under conventional barrier protection in accordance with guidelines of the University of California, San Diego and National Institutes of Health. Mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of University of California, San Diego.

Peripheral blood counts

Retro-orbital blood was collected in capillary tubes (Science Lab). Peripheral blood (50 μl) was collected in microtainer tubes with EDTA (Beckton Dickinson) and analyzed with a Blood Analyzer (Becton Dickinson).

Quantitative PCR analysis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Total cellular RNA isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen) was used for synthesis of cDNA with a Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen), followed by quantification of cDNA by quantitative RT-PCR (primer sequences, Supplementary Table 1)44. All values were normalized to the abundance of cyclophilin mRNA, then normalized values were divided by the wild-type value to obtain the relative value. The concentration of IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor in serum and culture supernatants was measured with a DuoSet ELISA Development system (R&D Systems).

Progenitor cell cultures

Bone marrow was isolated and single cells were collected by grinding of bone marrow through 45-μm filters (Millipore), followed by resuspension in Methocult 03534 medium (StemCell Technologies). Cells were plated onto 35 × 10mm CELLSTAR tissue culture dishes, and assessed for GM-CFU after 10 d at 37 °C according to the morphologic criteria described in the manufacturer’s manual (Methocult). Single colonies (GM-CFU) were photographed with a Leica DM IRB microscope equipped with a Leica DFC 290 camera and then colonies viewed with a Zeiss Stemi SV11 microscope were picked up with a pipet tip, followed by cytospins with Cytospin equipment. Cells were stained with Giemsa and photographed with an Olympus BX 41 microscope equipped with a Olympus Color View camera.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA from Ly6G+ neutrophils was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and purified with an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). Biotinylated cRNA was synthesized with an RNA Amplification kit according to the manufacturer’s directions (Ambion). Biotin-labeled cRNA was hybridized to a MouseRef-8 Expression BeadChip (Illumina) and results were analyzed with BeadStudio v3.1 software. Partek software was used for data analysis and quality control. Readings were adjusted by quantile normalization and the intensity of genes of interest, chosen by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, was normalized to the mean of selected genes. Genes with an intensity greater than the mean intensity of the selected genes are in red; genes with an intensity lower than the mean intensity are in green.

In vitro viability assay

Purified Ly6G+ peritoneal neutrophils obtained after thioglycollate injection were cultured at a density of 1 × 106 cells per ml in RPMI medium plus 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Samples (100 μl) were collected at various time points and propidium iodide exclusion was used for measurement of cell death as described45. For the proliferation of mature neutrophils, peritoneal neutrophils were collected at various time points and fixed overnight at −20 °C in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry for subdiploid DNA content.

Neutrophil killing assay

Peritoneal neutrophils were collected and resuspended at a density of 3.3 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI medium plus 2% (vol/vol) FBS. GAS bacteria were grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco), then were diluted and grown to mid-log phase. Bacteria were resuspended in RPMI medium plus 2% (vol/vol) FBS and then were added to siliconized tubes containing 1 × 106 suspended neutrophils at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 or 0.1 bacteria per cell. An aliquot of each tube (25 μl) was diluted and immediately plated on Todd-Hewitt agar (THA; Difco) for counting (time = 0). Tubes were placed under rotation at 37 °C and 25-μl aliquots were diluted and plated at each time point. In control assays examining the inhibition of GAS growth by wild-type neutrophils, bacteria proliferated to 50–75% greater numbers in medium with heat-killed neutrophils than in medium containing live neutrophils.

Mouse skin infection

Overnight cultures of GAS bacteria were diluted and grown to mid-log phase in Todd-Hewitt broth. Bacteria were concentrated and mixed 1:1 with sterile Cytodex beads (Sigma). An inoculum of 1 × 108 colony-forming units was injected subcutaneously into the shaved backs of mice. Lesions were measured daily and mice were killed on day 4. Lesions were excised, homogenized, diluted and plated for counting of surviving bacteria46.

Transduction of bone marrow cells

Equal numbers of bone marrow cells were transduced according to established methods through the use of a lentivirus containing a luciferase reporter controlled by the cytomegalovirus promoter47,48. Bioluminescence was measured with an in vivo imaging system (IVIS 200; Caliper).

Cell cycle analysis of progenitor populations

The cell-cycle status of each cell population was assessed with a Click-iT EdU Flow Cytometry Assay kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes–Invitrogen). EdU (200 μg in saline) was administrated to each mouse by intraperitoneal injection 3 h before mice were killed. Bone marrow was collected as described above and was kept at 4 °C until fixation. After being counted, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-CD34 (RAM34; eBioscience); phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD115 (antibody to macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor; AFS98; eBioscience); phycoerythrin-indodicarbocyanine–conjugated lineage (Lin) antibodies (anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-Ter119 (TER-119) and anti-CD127 (A7R34); all from eBioscience); phycoerythrin-indotricarbocyanine–conjugated anti-Gr-1 (8C5; eBioscience); allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD27 (LG.7F9; eBioscience); Alexa Fluor 680–conjugated anti-FcγRII/III (93; made in-house (I.L.W. laboratory)); allophycocyanin–Alexa Fluor 750–conjugated anti-c-Kit (2B8; eBioscience); Pacific blue–conjugated anti-Sca-1 (E13-161.7; made in-house (I.L.W. laboratory)); and Pacific orange–conjugated anti-Mac-1 (M1/70; made in-house (I.L.W. laboratory)). Cells (5 ×104 from each population) were sorted with a FACSAria (Beckton Dickinson) on the basis of a combination of cell-surface-marker expression as follows: CMP, Lin−CD27+c-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/IIIlo–neg; GMP. Lin−CD27+c-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/IIIhi; pre-granulocytes, Lin−CD27−c-Kit−CD115−Mac-1+Gr-1−; and granulocytes, Lin−CD27−c-Kit−CD115−Mac-1+Gr-1+. Sorted cells were processed for detection of the incorporation of EdU. Cells were fixed and made permeable and were allowed to react with Click-iT Alexa Fluor 488. DNA was stained with CellCycle 633-red. Processed cells were analyzed with a FACSAria. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo 8.8.6 software (TreeStar). An unpaired Student-t test after variance validation by F-test on Prism 5 software (GraphPad) was used for all statistical comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as averages ± s.d.. Differences between averages were analyzed by Student’s t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Kaushansky, G. Wulf and N. Zatula for advice and support; L. Jerabek and A. Mosley for laboratory and animal management, C. Richter and N. Teja for antibody production; and the National Clinical Trial & Research Center at National Taiwan University Hospital, and the Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Core, Research Center for Medical Excellence at National Taiwan University, Taiwan, ROC for microarray services and assistance in data analysis. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI043477 to M.K., AI77780 to V.N. and U01HL099999-02 to I.L.W.), National Taiwan University (L.-C.H.), National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan (NHRI-EX99-9825SC to L.-C.H.). Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America (T.E.), California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (J.S.) and American Cancer Society (M.K. and I.L.W.).

Footnotes

Accession codes. UCSD-Nature Signaling Gateway (http://www.signaling-gateway.org): A001645, A001172 and A003663; GEO: microarray data, GSE25211.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.S. and A.M.T. contributed equally to this work. L.-C.H. and T.E. designed and did most of the experiments; M.K. helped in designing experiments; M.K., T.E., and L.-C.H. wrote the paper; J.S. and I.L.W. planned and did most of the progenitor cell analyses; A.M.T. and V.N. planned and did the bacterial killing experiments; and C.-Y.L., T.-Y.L, G.-Y.Y., L.-C.L., V.T., U.S. and T.A. helped with some of the experiments.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/natureimmunology/.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/.

References

- 1.Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klebanoff SJ, Clark RA. The Neutrophil: Function and Clinical Disorders. Elsevier/North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1978. pp. 5–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quie PG. The phagocytic system in host defense. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1980;24:30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burg ND, Pillinger MH. The neutrophil: function and regulation in innate and humoral immunity. Clin Immunol. 2001;99:7–17. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann V, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Kockritz-Blickwede M, Nizet V. Innate immunity turned inside-out: antimicrobial defense by phagocyte extracellular traps. J Mol Med. 2009;87:775–783. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundqvist-Gustafsson H, Bengtsson T. Activation of the granule pool of the NADPH oxidase accelerates apoptosis in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:196–204. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metcalf D. Stem cells, pre-progenitor cells and lineage-committed cells: are our dogmas correct? Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;872:289–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, et al. Identification of Lin−Sca1+kit+CD34+Flt3− short-term hematopoietic stem cells capable of rapidly reconstituting and rescuing myeloablated transplant recipients. Blood. 2005:105–2723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalf D, Nicola NA. The Hemopoietic Colony Stimulating Factors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1995. pp. 109–165. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greten FR, Karin M. The IKK/NF-κB activation pathway-a target for prevention and treatment of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacker H, Karin M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re13. doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straus DS. Design of small molecules targeting transcriptional activation by NF-κB: overview of recent advances. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2009;4:823–836. doi: 10.1517/17460440903143739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baud V, Karin M. Is NF-κB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagashima K, et al. Rapid TNFR1-dependent lymphocyte depletion in vivo with a selective chemical inhibitor of IKKβ. Blood. 2006;107:4266–4273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greten FR, et al. NF-κB is a negative regulator of IL-1β secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKβ. Cell. 2007;130:918–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbalaviele G, et al. A novel, highly selective, tight binding IκB kinase-2 (IKK-2) inhibitor: a tool to correlate IKK-2 activity to the fate and functions of the components of the nuclear factor-κB pathway in arthritis-relevant cells and animal models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:14–25. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruocco MG, et al. IκB kinase (IKK) β, but not IKKα, is a critical mediator of osteoclast survival and is required for inflammation-induced bone loss. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1677–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hestdal K, et al. Characterization and regulation of RB6–8C5 antigen expression on murine bone marrow cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitale C, et al. Engagement of p75/AIRM1 or CD33 inhibits the proliferation of normal or leukemic myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15091–15096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Edelstein LC, Gelinas C. The Rel/NF-κB family directly activates expression of the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-xL. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2687–2695. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2687-2695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boise LH, et al. Bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu L, et al. Constitutive NF-κB and NFAT activation leads to stimulation of the BLyS survival pathway in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2006;107:4540–4548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resnitzky D, Hengst L, Reed SI. Cyclin A-associated kinase activity is rate limiting for entrance into S phase and is negatively regulated in G1 by p27Kip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4347–4352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catlett-Falcone R, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling confers resistance to apoptosis in human U266 myeloma cells. Immunity. 1999;10:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He G, et al. Hepatocyte IKKβ/NF-κB inhibits tumor promotion and progression by preventing oxidative stress-driven STAT3 activation. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horwitz BH, Scott ML, Cherry SR, Bronson RT, Baltimore D. Failure of lymphopoiesis after adoptive transfer of NF-κB-deficient fetal liver cells. Immunity. 1997;6:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossmann M, et al. The combined absence of the transcription factors Rel and RelA leads to multiple hemopoietic cell defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11848–11853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senftleben U, Li ZW, Baud V, Karin M. Ikkβ is essential for protecting T cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 2001;14:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanley ER, Bartocci A, Patinkin D, Rosendaal M, Bradley TR. Regulation of very primitive, multipotent, hemopoietic cells by hemopoietin-1. Cell. 1986;45:667–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueda Y, Cain DW, Kuraoka M, Kondo M, Kelsoe G. IL-1R type I-dependent hemopoietic stem cell proliferation is necessary for inflammatory granulopoiesis and reactive neutrophilia. J Immunol. 2009;182:6477–6484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greten FR, et al. Ikkβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane AA, Ley TJ. Neutrophil elastase is important for PML-retinoic acid receptor α activities in early myeloid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:23–33. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.23-33.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jamieson CH, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:657–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genovese MC, et al. Combination therapy with etanercept and anakinra in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have been treated unsuccessfully with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1412–1419. doi: 10.1002/art.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuida K, et al. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 β converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu LC, et al. A NOD2-NALP1 complex mediates caspase-1-dependent IL-1β secretion in response to Bacillus anthracis infection and muramyl dipeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7803–7808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802726105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Temkin V, Huang Q, Liu H, Osada H, Pope RM. Inhibition of ADP/ATP exchange in receptor-interacting protein-mediated necrosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2215–2225. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2215-2225.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kranich J, et al. Follicular dendritic cells control engulfment of apoptotic bodies by secreting Mfge8. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1293–1302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrahamsson AE, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β missplicing contributes to leukemia stem cell generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3925–3929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900189106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breckpot K, et al. Lentivirally transduced dendritic cells as a tool for cancer immunotherapy. J Gene Med. 2003;5:654–667. doi: 10.1002/jgm.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.