Abstract

The aim of this study is to demonstrate that in molecular dynamical systems with the underlying bi- or multistability, the type of noise determines the most strongly attracting steady state or stochastic attractor. As an example we consider a simple stochastic model of autoregulatory gene with a nonlinear positive feedback, which in the deterministic approximation has two stable steady state solutions. Three types of noise are considered: transcriptional and translational – due to the small number of gene product molecules and the gene switching noise – due to gene activation and inactivation transitions. We demonstrate that the type of noise in addition to the noise magnitude dictates the allocation of probability mass between the two stable steady states. In particular, we found that when the gene switching noise dominates over the transcriptional and translational noise (which is characteristic of eukaryotes), the gene preferentially activates, while in the opposite case, when the transcriptional noise dominates (which is characteristic of prokaryotes) the gene preferentially remains inactive. Moreover, even in the zero-noise limit, when the probability mass generically concentrates in the vicinity of one of two steady states, the choice of the most strongly attracting steady state is noise type-dependent. Although the epigenetic attractors are defined with the aid of the deterministic approximation of the stochastic regulatory process, their relative attractivity is controlled by the type of noise, in addition to noise magnitude. Since noise characteristics vary during the cell cycle and development, such mode of regulation can be potentially employed by cells to switch between alternative epigenetic attractors.

Keywords: Gene expression, Bistability, Stochastic processes, Epigenetic attractors

1. Introduction

From the mathematical perspective intracellular regulatory processes can be considered as stochastic dynamical systems. Stochasticity arises due to the limited number of reacting molecules such as gene copies, mRNA or proteins. In systems with underlying bistability, even for low noise, the stochastic trajectories exhibit stochastic jumps between basins of attraction and thus diverge qualitatively from the deterministic solutions. The relative stability of steady states depends on the system volume (or noise strength) (Vellela and Qian, 2009). In this study, we analyze the bistable stochastic system with three different types of noise and demonstrate that the dominating type of noise determines the most strongly attracting steady state (global stochastic attractor). That is, two systems with the same deterministic approximation may have qualitatively different stationary probability distributions (SPD) depending on the noise characteristic, even in the zero noise limit.

We consider two models of gene expression with autoregulation. We will assume that the gene is positively regulated by its own product in a cooperative manner, which leads to the nonlinear positive feedback and bistability. Single-cell experiments suggest that gene expression can be described by a three-stage model (Blake et al., 2003; Raser and O'Shea, 2004). The gene promoter can switch between two states (Ko, 1991; Raj et al., 2006; Chubb et al., 2006), one active and one inactive. Such transitions could be associated with binding and unbinding of repressors or transcription factors or with changes in chromatin structure. Transcription can only occur if the promoter is active. The next two stages are mRNA transcription and protein translation. In certain cases when mRNA is very unstable and quickly translated, transcription and translation processes can be lumped together (Kepler and Elston, 2001; Hornos et al., 2005). The resulting model has thus two stages: gene regulation and protein synthesis. Such simplification allows for analytical treatment of the problem, however, lumping of transcription and translation processes may influence the impact of feedback on noise strength (Marquez-Lago and Stelling, 2010). Therefore, in addition to the simplified two-stage model we analyze numerically a more detailed three-stage model in which processes of gene regulation, mRNA transcription and protein translation are explicitly included. The considered models have three types of noise: transcriptional and translational – due to the limited number of product molecules, and gene switching noise – due to gene state transitions.

Transcriptional and translational noises are characteristic for prokaryotes in which the mRNA and protein numbers are very small (McAdams and Arkin, 1997; Kierzek et al., 2001; Ozbudak et al., 2002). Recently, Taniguchi et al. (2010) quantified the mean expression of more than 1000 Escherichia coli genes and found that the most frequent average protein number is of order of 10, while the most frequent average mRNA number is smaller than one. The gene switching in prokaryotes is thought to be very fast and thus gene regulation is frequently considered in the so called adiabatic approximation (Hornos et al., 2005), as a process that includes only mRNA transcription and protein translation (Thattai and Oudenaarden, 2001; Swain et al., 2002; Shahrezaei and Swain, 2008).

Gene switching noise is important in eukaryotes (Blake et al., 2003; Ko, 1991; Chubb et al., 2006; Raj and Oudenaarden, 2009) in which the transitions between the on and off states are much less frequent. Analysis of gene expression in mammalian cells showed that mRNA is synthesized in bursts, during periods of time when the gene is transcriptionally active (Raj et al., 2006). Slow gene switching can result in bimodal mRNA and protein probability distributions even in systems without underlying bistability (Hornos et al., 2005; Shahrezaei and Swain, 2008). Bimodality may arise also without bistability in two-stage cascades in which the regulatory gene produces transcription factors that have a nonlinear effect on the activity of the target gene (Ochab-Marcinek and Tabaka, 2010). In contrast to prokaryotes, in eukaryotes the characteristic mRNA and protein numbers are much larger. Therefore the transcriptional and translational noises in many cases may be neglected (Lipniacki et al., 2006, 2007; Bobrowski et al., 2007) or considered in the diffusion approximation (van Kampen, 2007; Kepler and Elston, 2001). Cell cycle transcriptional regulator gene SWI6 in yeast is an example of a gene with expression noise originating almost only from gene switching noise, while transcriptional noise is negligible (Becksei et al., 2005).

The bistable regulatory elements received a lot of attention in the last decade as they enhance heterogeneity and may allow cells in multicellular organism to specialize and specify their fate. Decisions between cell death, survival, proliferation and senescence are associated with bistability and stochasticity, magnitude of which controls transition rates between the particular attractors (Hasty et al., 2000; Puszynski et al., 2008; Lipniacki et al., 2008). In prokaryotes the bistability is regarded as an optimal strategy for coping with infrequent changes in the environment (Kussell and Leibler, 2005).

The simplest regulatory element exhibiting bistability is the self-regulating gene controlled by a nonlinear positive feedback (Hornos et al., 2005; Walczak et al., 2005; Karmakar and Bose, 2007; Hat et al., 2007; Schultz et al., 2007; Siegal-Gaskins et al., 2009). While not often found as an isolated entity, the self-regulating gene is a common element of biological networks; for example, 40% of E. coli transcription factors negatively regulate their own transcription (Rosenfeld et al., 2002). van Sinderen and Vemnema (1994) demonstrated that transcription factor comK acts as an autoregulatory switch in Bacillus subtilis. The synthetic auto-regulatory eukaryotic gene switch was studied in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Becskei et al., 2001). The other intensively studied regulatory element exhibiting bistability is the toggle switch – a pair of mutual repressors (Lipshtat et al., 2006; Chatterjee et al., 2008). A classical example is the double-negative regulatory circuit governing alternative lysogenic and lytic states of phage lambda (Ptashne, 2004), lactose utilization network (Ozbudak et al., 2004) or Delta–Notch regulation (Sprinzak et al., 2010).

Despite the low copy number of proteins and mRNAs genetic switches may exhibit very low transition rates, resulting in stable epigenetic properties that persist in simplest organisms for many generations (Ptashne, 2004; Acar et al., 2005), reviewed by Chatterjee et al. (2008). The attractors of genetic networks can be associated with distinct cell types achieved during cell differentiation (Acar et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006). In a single cell, in the long time scale the relative occupancy of steady states is determined by their relative stability. The same, however, may not be true for cell population when the two steady states are associated with different growth rates. As demonstrated, by Nevozhay et al. (2012) using synthetic bistable gene circuit, the fraction of cells in the most strongly attracting steady state may be low, if these cells have lower growth rate than cells in the less stable steady state. Thus, in the context of cell population the relative occupancy of a given state is defined by rates of state to state transitions (or memory) and fitness associated with particular steady states.

The paper is organized as follows: in the following section we consider the two-stage gene autoregulation model and its three approximations:

the deterministic approximation,

the continuous approximation with the gene switching noise only,

and the adiabatic approximation with the transcriptional and translational noise only.

Based on two last approximations, we demonstrate that the type of noise determines the global attractor. Then, we numerically calculate the SPD in the case when two types of noise are present and show that the most strongly attracting steady state is determined by the prevalent type of noise. For a relatively large subdomain in the parameter space, the SPD is concentrated either in one or the other stable steady state depending on the dominating type of noise. We supplement our consideration of the two-stage model by the analysis of the SPD following from Langevin equations in which the white noise term is added to the equation obtained in the deterministic approximation.

Finally, to confirm our findings, we consider a more detailed, three-stage model in which processes of gene regulation, mRNA transcription and protein translation are explicitly included, which enables distinguishing of transcriptional and translational noises. Within the latter model we demonstrate that the global attractor is determined by relative magnitudes of the transcriptional and gene switching noises, while the translational noise is the least important. We conclude discussing these two types of noise in the context of gene expression in bacteria and eukaryotes.

2. Results

2.1. Two-stage model and its approximations

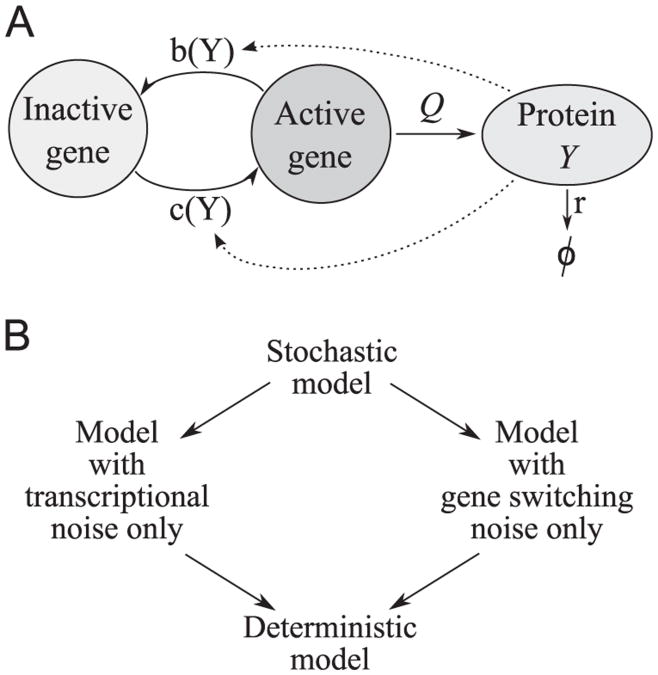

We assume that the gene may be in one of the two states – active or inactive, Fig. 1A. In this model we assume that the protein is synthesized directly from the gene, with the rate constant Q only when the gene is active and is degraded with the rate constant r. We chose time units in which r = 1. The rate constant Q is proportional to the product of transcription and translation rate constants Q1 and Q2. The autoregulation arises when gene activation and/or inactivation rates (c(Y) and b(Y)) depend on the level of synthesized protein Y. The model defines a time continuous Markov process described by two random variables: the gene state G(t) ∊{0,1} and number of protein molecules Y(t) ∊ ℕ. The resulting transition propensities are

Fig. 1.

Two-stage gene expression model. (A) Schematic of the model (B) Stochastic model and its three approximations.

| (1) |

Let gn denote the probability that {G, Y} = {1, n} and hn denote the probability that {G, Y} = {0, n}. Probabilities gn and hn follow a countable set of chemical master equations:

| (2) |

where we set g−1 = 0 to close the first of Eqs. (2).

Here, we focus on such c(n) and b(n) that define the positive nonlinear autoregulation leading to bistability. Thus, we assume

| (3) |

Such type of regulation arises in the case when the gene is switched on by its own product in a cooperative manner or by the other transcription factor present at some constant level. In order to analyze systems with various average numbers of proteins, but having the same deterministic limit, the nonlinear term (c2/Q2)n2 is scaled by Q, which is equivalent to the assumption that the gene switching rates are proportional to the protein concentration rather than to the protein number.

Even in the stationary case, the system (2) can be solved analytically using a moment generating function only in the case when c(n) and b(n) are both constant, or one of them is constant and the other is linear in n (Hornos et al., 2005). In our case (3), due to the second order nonlinearity in c(n), the method proposed by Hornos et al. (2005) leads to the third order ordinary differential equation, we failed to solve. We will thus estimate the marginal SPD fn = gn + hn corresponding to the exact model by Monte Carlo simulations of the system (1). Analytically, we will study three approximations to the exact model: the continuous approximation with the gene switching noise only, the adiabatic approximation with the transcriptional noise only, and the deterministic approximation, Fig. 1B.

2.1.1. Deterministic approximation

This classical approximation (Ackers et al., 1982) is justified when the transition rates c(n) and b(n) are much greater than one, and simultaneously the characteristic number of protein molecules is very large. In such a case one may consider y=Y/Q as a continuous variable. The scaled protein level y(t) is given by a single ordinary differential equation:

| (4) |

In our specific case, c(y) = c0 + c2y2 and b(y) = b0, thus the stationary solutions of Eq. (4) are the real roots of the third order polynomial:

| (5) |

We will focus on the bistable case when W has three real roots such that 0 <y1 < y2 < y3 < 1. Steady states y1 and y3 are stable, while y2 is unstable. Due to the fact that W has the same coefficient at the third and the second power, its roots satisfy y1 + y2 + y3 = 1. The original coefficients b0, c0, c2 may be recovered from the roots by the following relations:

| (6) |

Due to relation y3 = 1−y1−y2, the (y1, y2, y3) parameter space may be reduced to the domain D ∋ {y1,y2} such that y1 < y2 and 1−y1−y2 = y3 > y2.

2.1.2. Continuous approximation

The model with noise resulting only from gene switching was analyzed previously in Karmakar and Bose (2007). When the characteristic number of protein molecules is very large, as in the deterministic case, y = Y/Q may be considered a continuous variable which follows:

| (7) |

Where G, as in the exact model, is given by the process (1). These assumptions define a time continuous piece-wise deterministic Markov process. Probabilities gn(t) and hn(t) are now replaced by the continuous functions g(y,t), h(y,t) that satisfy (Lipniacki et al., 2006; Bobrowski et al., 2007)

| (8) |

| (9) |

The above system has the following stationary solution (Hat et al., 2007)

| (10) |

In our specific case, when c(y) = c0 + c2y2 and b(y) = b0, the marginal SPD f(y) = g(y) + h(y) may be expressed analytically:

| (11) |

where C is such that

Now, we will replace original coefficients b0, c0, c2 by y1, y2 (see Eq. (6)) and introduce σ := 1/b0. Let us notice that for such defined σ all gene switching noise rates b0, c0, c2 are inversely proportional to σ. The coefficient σ is an inverse of the adiabaticity coefficient, introduced in Hornos et al. (2005), and will be referred to as a measure of gene switching noise. Specifically, we will consider the SPD in the limit σ → 0. In this limit the SPD given by Eq. (11) converges either to the Dirac delta in y1 or in y3, i.e. to δ(y1), or to δ(y3) for all {y1,y2} ∊D, except {y1,y2} such that

| (12) |

Eqs. (6), (11) and (12) define (in the implicit form) the separatrix Scontinuous

| (13) |

where

| (14) |

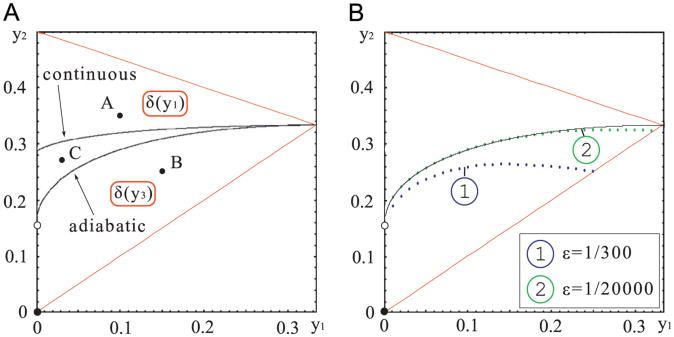

That is, in the continuous approximation, the bistability domain D is split by the separatrix Scontinuous (on which 0 < C1 < ∞) into two subdomains. For {y1, y2} above the separatrix ScontinuousC1 = ∞ and the SPD converges to δ(y1) as σ → 0, while for {y1, y2} below the separatrix ScontinuousC1 = 0 and the SPD converges to δ(y3), see Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

Bistability domain in {y1, y2} space. Panel (A): the two black curves divide the domain into three subdomains: in the subdomain

(containing point A), the SPDs of adiabatic and continuous approximations concentrate in y1; in the subdomain

(containing point A), the SPDs of adiabatic and continuous approximations concentrate in y1; in the subdomain

(containing point B), the SPDs of the two approximations concentrate in y3. In the subdomain

(containing point B), the SPDs of the two approximations concentrate in y3. In the subdomain

(bounded by separatrices Sadiabatic and Scontinuous), the SPD for the continuous approximation (ε = 0) is concentrated in y3 while the SPD for the adiabatic approximation (σ = 0) is concentrated in y1. Panel (B): continuous line – analytically calculated division curve y2(y1) for the adiabatic approximation (σ = 0) in the ε→0 limit; dotted lines are the separation lines for a finite noise parameter ε = 1/300 and ε = 1/20,000.

(bounded by separatrices Sadiabatic and Scontinuous), the SPD for the continuous approximation (ε = 0) is concentrated in y3 while the SPD for the adiabatic approximation (σ = 0) is concentrated in y1. Panel (B): continuous line – analytically calculated division curve y2(y1) for the adiabatic approximation (σ = 0) in the ε→0 limit; dotted lines are the separation lines for a finite noise parameter ε = 1/300 and ε = 1/20,000.

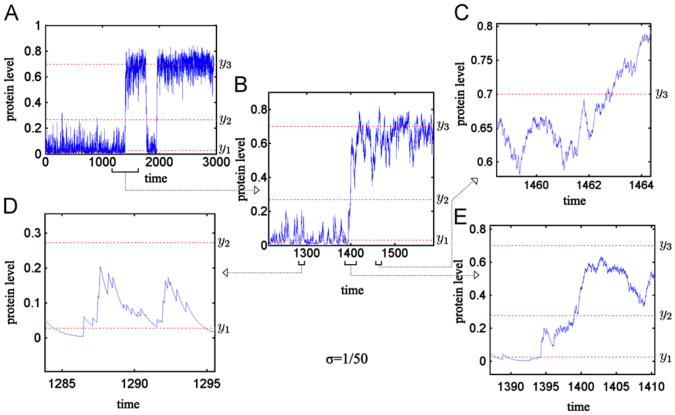

Simulations of the stochastic process in the continuous approximation, i.e. simulation of a piece-wise continuous process given by Eqs. (1) and (7), were performed using the Haseltine and Rawlings (2002) algorithm (Lipniacki et al., 2007). These simulations show significantly different behavior of the protein level y(t) near each of the two stable stationary points (see Fig. 3C and D). When the trajectory is in the vicinity of y1 (Fig. 3D) the characteristic time for which the gene is switched off ∼ 1/c(y1) is much longer than the characteristic time for which the gene is switched on ∼ 1/b0. When the trajectory is in the vicinity of y3 (Fig. 3C) these two times are similar. The characteristic departures from both states y1 and y3 are larger towards y2 than in the opposite direction. For low noise there are relatively few transitions through the unstable state y2. The frequency of these transitions decreases to zero with decreasing noise.

Fig. 3.

Two-stage model: Stochastic simulation trajectory for the continuous approximation, ε = 0. Protein level obtained in the numerical simulation for σ = 1/50. The three steady states y1 = 0:03 (stable), y2 = 0:27 (unstable) and y3 = 0:7 (stable) of the deterministic approximation are shown by the dashed lines. For such y1, y2, y3 (corresponding to point C in Fig. 2A) the SPD of the continuous approximation converges to δ(y3) as σ→0, see Fig. 5C. Time is given in units in which the protein degradation rate constant is equal to 1. Panel (B) shows the zoomed region from Panel (A) around transition from the low to the high protein level, the further detail of this transition is shown in Panel (E); Panel (D) shows trajectory in the vicinity of the steady state y1; Panel (C) shows trajectory in the vicinity of the steady state y3.

2.1.3. Adiabatic approximation

This approximation is justified when transition rates c(n) and b(n) are much larger than the protein degradation rate constant. In such a case, G may be replaced (Hornos et al., 2005; Bobrowski, 2006) by its expected value G = G(n) = c(n)/(c(n) + b(n)). This approximation leads to a birth–death process with birth and death propensities:

| (15) |

As in the case of the continuous approximation, the simulations show that trajectories near each stable stationary point differ significantly, Fig. 4. The birth and death events are less frequent near y1 than near y3.

Fig. 4.

Two-stage model: Stochastic simulation trajectory for adiabatic approximation, σ = 0. Protein level obtained in the numerical simulation for ε = 1/100. The three steady states y1 = 0:03 (stable), y2 = 0.27 (unstable) and y3 = 0.7 (stable) of the deterministic approximation are shown by the dashed lines. For such y1, y2, y3 (corresponding to point C in Fig. 2A) the SPD of the adiabatic approximation converges to δ(y1) as ε→0, see Fig. 5C. Panel (B) shows the zoomed region from Panel (A) around transition from the low to high protein level, the detail of this transition is shown in Panel (E); Panel (D) shows trajectory in the vicinity of steady state y1; Panel (C) shows trajectory in the vicinity of steady state y3.

Let Fn denote the stationary probability that the number of protein molecules is equal to n. In the steady state the net probability current between neighboring states N and N+1 is equal to zero, i.e.

| (16) |

which gives Fn in the form:

| (17) |

Eq. (17) defines the discrete probability density function Fn when , which is satisfied provided that for sufficiently large j, B(i)/D(i + 1) < a < 1 for all i > j. Since B(i)/D(i + 1) < Q/n, the last condition holds. Now, we may choose F0 such that . We analyze the discrete probability density Fn for small ε = 1/Q. In the limit of ε→0, the adiabatic approximation converges to the deterministic approximation, and so the coefficient e will be considered as a measure of transcriptional and translational noise. Let FQ(y) := QFn, where y := n/Q, i.e. , where b(i/Q) := B(i), d(i/Q) := D(i). Now,

| (18) |

In the limit of ε → 0, d(i/Q + 1/Q)→d(i/Q). Next, replacing the sum by the integral, we obtain

| (19) |

thus

| (20) |

Since we get

| (21) |

where

| (22) |

The Laplace's method implies that in the limit of Q→∞, the function FQ(y) converges to the Dirac delta distribution δ(ym) in the unique global maximum ym of φ(y), provided that such global maximum exists. In our case b(y) = Q(c0 + c2y2)/(c0 + c2y2 + b0) and d(y) = Qy. Using Eqs. (6) and (22) we obtain

| (23) |

Since the extrema of FQ(y) coincide with the extrema of φ(y), the global maximum of φ(y) is either in y1 or y3, thus the SPD converges either to δ(y1) or to δ(y3) as Q → ∞. Only in the non-generic case, in which φ(y) has no global maximum, i.e. when

| (24) |

the SPD converges to the sum of two Dirac delta functions A1δ(y1)+A3δ(y3). Eqs. (23) and (24) define the separatrix Sadiabatic. For {y1, y2} above the separatrix Sadiabatic the SPD converges to δ(y1), while for {y1, y2} below the separatrix Sadiabatic the SPD converges to δ(y3) as ε→0, Fig. 2A. The allocation of probability mass depends also on the magnitude of noise. In Fig. 2B we show the separatrices, (defined as lines y2(y1) on which the SPD is equally distributed between the two basins of attraction) obtained from Eq. (17) for two values of ε. The separatrices converge to Sadiabatic as ε→0.

2.2. SPD dependence on the transcriptional and gene switching noise magnitudes

Simulations in the continuous and adiabatic models (see Figs. 3 and 4) were both performed for point C = {y1=0.03, y2 = 0.27} in the parameter space shown in Fig. 2A. For the continuous approximation the characteristic departures from the stable steady states y1 and y3 are of similar magnitude. The case of the adiabatic approximation is different. Here, the fluctuations around point y3 are much larger than around point y1. This suggests that the average time spent in the vicinity of point y1 before the transition to point y3 will be longer than the average time spent in the vicinity of point y3 before the reverse transition. As a result the SPD for the adiabatic approximation will concentrate around point y1, while for the continuous approximation the SPD will concentrate around y3. This effect should be even more pronounced in the low noise limit when the transitions between the two attractors are less frequent. Accordingly, as shown in Fig. 2A the separatrices Sadiabatic and Scontinuous are different, and together they bound domain

, such that in the zero noise limit for {y1,y2} ∊

, such that in the zero noise limit for {y1,y2} ∊

, the SPD of the continuous model converges to δ(y1), while the SPD of the adiabatic model converges to δ(y3). In the further analysis we consider the three sets of roots shown in Fig. 2A, i.e.

, the SPD of the continuous model converges to δ(y1), while the SPD of the adiabatic model converges to δ(y3). In the further analysis we consider the three sets of roots shown in Fig. 2A, i.e.

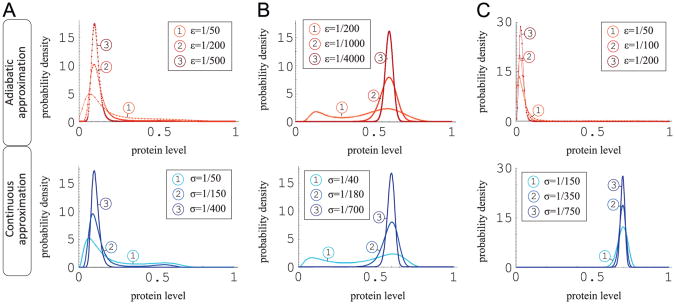

In Fig. 5, we compare the SPD of the adiabatic and of the continuous approximations. For {y1,y2} = A and {y1,y2} = B the SPDs obtained in both approximations are concentrated (in the low noise limit) in the vicinity of the same steady state, y1 and y3, respectively, for A and B. However, for {y1,y2} = C, the SPD of the adiabatic approximation is concentrated in the vicinity of y1, while the SPD of the continuous approximation is concentrated in the vicinity of y3. Let us also note that in case B the magnitude of noise controls the relative allocation of probability mass between basins of attraction of steady states y1 and y3.

Fig. 5.

The SPDs for the adiabatic and continuous approximations. Columns A, B and C correspond to points A, B and C in Fig. 2A. Upper row panels – the adiabatic approximation, lower row panels – the continuous approximation. For y1 = 0.03, y2 = 0.27, in the zero noise limit (column C), the SPDs of the adiabatic and the continuous approximations converge, respectively, to δ(y1), and δ(y3).

In the adiabatic approximation the gene switching noise σ is, by definition, identically 0. Similarly, in the continuous approximation the transcriptional and translational noise ε is identically 0. We thus showed that in the parameter subdomain C the system settles in the inactive state for ε/σ = ∞ (adiabatic approximation) and settles in the active state for ε/σ = 0 (continuous approximation). This suggests that there exist a range of parameters for which noise ratio ε/σ determines which of the two steady states is the most strongly attracting. We now verify this conjecture considering the exact model with different ε and σ values, see Fig. 6. To estimate the SPD we performed long-run Monte Carlo simulations of the system (1) using the Gillespie (1977) algorithm. For the analysis shown in Fig. 6, we chose C ={0.03,0.27} ∈

. Such a choice of {y1,y2} produces the equimodal SPD in the case when magnitudes of transcriptional and gene switching noises are comparable (and sufficiently large), i.e. ε = 1/300 and σ = 1/100. We observe that when magnitude of the transcriptional or gene-switching noise decreases to zero the SPD becomes unimodal. As expected from the analysis shown in Fig. 5, the SPD is concentrated in y1 as σ → 0 (adiabatic approximation limit), and in y3 as ε → 0 (continuous approximation limit). Therefore, we demonstrated that when two types of noise are present, their relative magnitudes determine the global attractor. This effect has an analog in equilibrium selection in evolutionary games (Miekisz, 2005).

. Such a choice of {y1,y2} produces the equimodal SPD in the case when magnitudes of transcriptional and gene switching noises are comparable (and sufficiently large), i.e. ε = 1/300 and σ = 1/100. We observe that when magnitude of the transcriptional or gene-switching noise decreases to zero the SPD becomes unimodal. As expected from the analysis shown in Fig. 5, the SPD is concentrated in y1 as σ → 0 (adiabatic approximation limit), and in y3 as ε → 0 (continuous approximation limit). Therefore, we demonstrated that when two types of noise are present, their relative magnitudes determine the global attractor. This effect has an analog in equilibrium selection in evolutionary games (Miekisz, 2005).

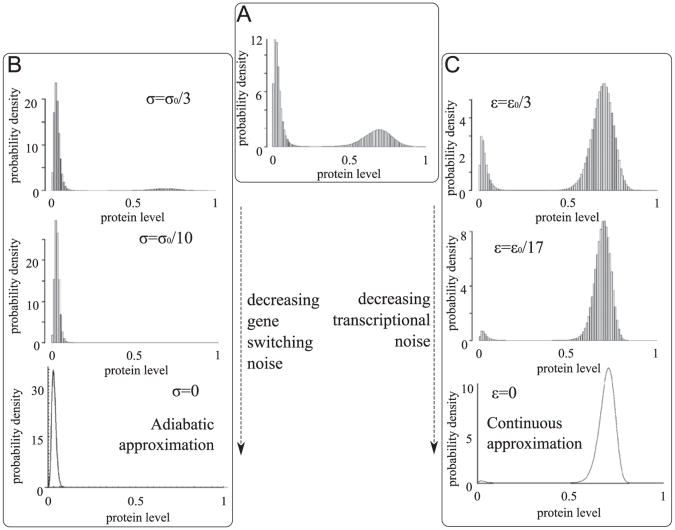

Fig. 6.

The SPD of the two-stage model obtained in Monte Carlo simulations for y1 = 0.03, y2 = 0.27 (point C in Fig. 2A). Panel (A) shows the bimodal SPD in the case when the magnitudes of two types of noise are comparable: ε0 = 1/300, σ0 = 1/100. Panel (B) consisting of three subpanels shows the SPD for the constant transcriptional noise ε0 and decreasing gene switching noise σ. Panel (C) also consisting of three subpanels, shows the SPD for the constant gene switching noise σ0 and decreasing transcriptional noise ε. The lowest subpanels show the analytically calculated SPDs for the adiabatic and continuous approximations.

2.3. Langevin approach

The classical approach to complex stochastic systems involves Langevin equation in which various noise sources are replaced by white noise, which magnitude is either constant (additive noise) or is a function of the solution (multiplicative noise), in the simplest case is proportional to the solution (as in geometric Brownian motion equation). Here, we follow this procedure starting from the deterministic approximation of our model. Langevin-Ito equation extending deterministic equation (4) is

| (25) |

and ξ(t) is a Gaussian white noise, with

| (26) |

In this description √B(y)/V is identified as noise intensity, where V is the volume of the reactor. In the case of additive noise B(y) = const = B0. We consider also the case of multiplicative noise, assuming that its magnitude is proportional to y(t) and set B(y) = y. The other choice of multiplicative noise was made by Frigola et al. (2012), who assumed that magnitude of noise is proportional to the sum of birth and death rates (in our case it would be G(y) +y). One should notice that such a choice is in a sense arbitrary since adding any function f(y) to birth and death rates, leaves deterministic equation unchanged but changes its stochastic counterpart.

The Fokker–Planck equation corresponding to the above Langevin–Ito equation reads (van Kampen, 2007)

| (27) |

In the stationary case (∂F(y,t)/∂t = 0) this equation solves explicitly to

| (28) |

where φ(y)

| (29) |

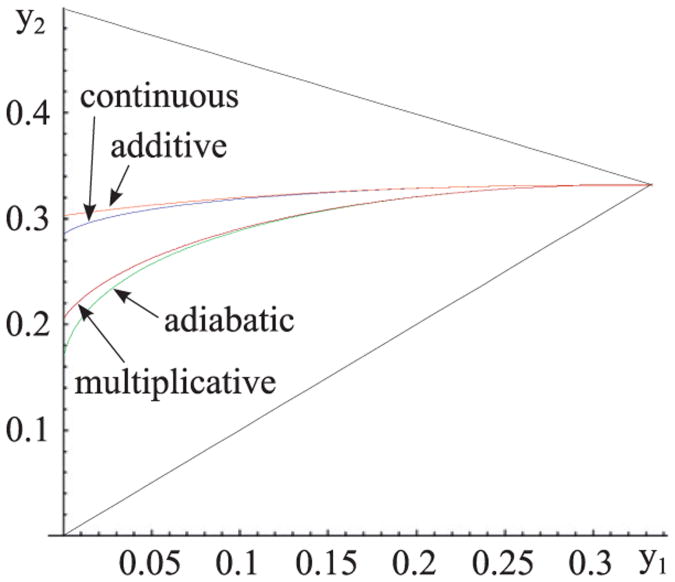

has the meaning of a potential. In the case of additive noise, B(y) = B0, φ(y) is proportional to the deterministic potential . Analogously to the previous section the separatrices Sadditive and Smultiplicative are given in implicit form by φ(y1) = φ(y3). In Fig. 7 we show them together with previously determined separatrices Sadiabatic and Scontinuous in y1,y2 plane. In order to calculate these two new separatrices, we make use of Eqs. (6) giving c0 and c2 as functions of y1,y2 and y3.

Fig. 7.

Separatrices the calculated for the continuous and adiabatic approximations (as in Fig. 2A) compared with those resulting from the Fokker–Plank equation with assumed either additive or multiplicative noise. For each of approximations for y1, y2 above the separatrix, the global attractor is in y1, while for y1, y2 below the separatrix the global attractor is in y3.

The alternative way of calculating separatrices Sadditive and Smultiplicative involves the, so called, Dynkin equation (dual to Fokker–Plank equation) for the first mean passage time (MFPT) Tθ,γ(y) from y to the absorbing boundary at y = θ, with the reflective boundary at y = γ (see the book of Gardiner, 2004 for the MFPT introduction, and Nevozhay et al., 2012; Frigola et al., 2012 for the recent relevant application of this method):

| (30) |

The boundary conditions are Tθ,γ(θ) = 0, and dTθ,γ/dy = 0 at y = γ. In the low noise limit, the probability mass fraction concentrated in the vicinity of the steady state y1 is (T3→1)/(T3→1 + T1→3), where T1→3 is the MFPT from y1 to y3 and T3→1 is the MFPT from y3 to y1. To calculate T1→3 we set θ=y3 and γ = 0, while to calculate T3→1 we set θ=y1 and γ = ∞. Our separatrices are given by equality T3→1 =T1→3 in V→∞ limit. Obviously, MFPTs give more information than just the probability mass allocation as they account for cell memory (Nevozhay et al., 2012). Times T1→3 and T3→1 may be obtained in explicit integral forms from Eq. (30) (Gardiner, 2004).

In summary, using the classical Langevin approach we confirmed that a prediction of the most strongly attracting steady state, strongly depends on assumed noise, here, either additive or multiplicative. As one could expect, the additive noise separatrix closely matches with that of continuous approximation in which noise results solely from gene switching, while the multiplicative noise separatrix closely matches with that of the adiabatic approximation for which the magnitude of noise grows with the number of molecules. As already said, in the original stochastic model the most strongly attracting steady state is determined by the relative magnitude of gene switching, transcriptional and translational noises, and thus in general it may not be predicted basing on the Langevin equation in which all noise sources are lumped together and replaced by white noise. By considering arbitrary noise functions we showed recently, that any steady state can became a global stochastic attractor for particular choice of noise (Zuk et al., 2012).

2.4. Three-stage model

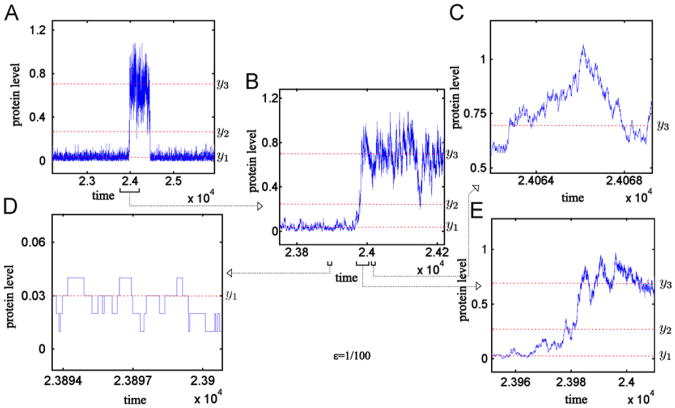

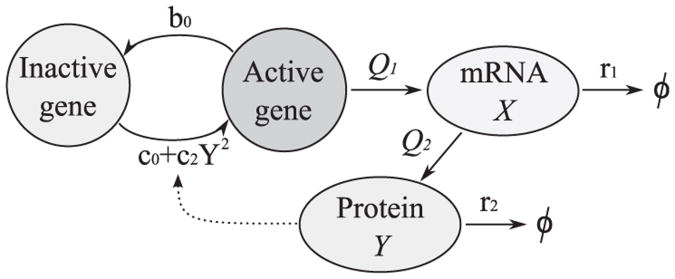

In this section we consider a more detailed model of an autoregulatory gene and demonstrate that the choice of the most strongly attracting steady state is governed by the relative magnitudes of gene switching, transcriptional and translational noises. The following three processes are included in the model: the gene activation/inactivation, mRNA transcription and protein translation, Fig. 8. The mRNA is synthesized with the rate constant Q1 and is degraded with the rate constant r1. The protein is translated on the mRNA template with the rate constant Q2 and is degraded with the rate constant r2. The transcriptional and translational noises are characterized, respectively, by parameters ε1 = r1/Q1 and ε2 = r2/Q2. Thus the characteristic number of proteins (achieved when the gene is turn on for infinitely long time) is equal to N = 1/(ε1ε2). As in the previous model we assume that the gene may be in one of two states: inactive G=0 (no mRNA synthesis) or G=1, active due to binding of its own protein or some transcription factor implicitly present in the model at constant concentration. The transition from state G=0 to G=1 proceeds with rate c0 + (c2/N2)Y2 (where Y is the number of proteins), while the transition from G= 1 to G=0 proceeds with constant rate b0. The coefficient c2 describing cooperative auto-activation scales with N2, which is equivalent to the assumption that protein binding rate is proportional to the concentration rather than to the number of molecules. It is assumed that the cell size is proportional to the characteristic protein number N. As in the previous model the gene switching noise is characterized by the parameter σ = 1/b0. The model defines a time continuous Markov process described by three random variables: the gene state G(t)A {0,1}, number of mRNA molecules X(t) ∈ ℕ and number of proteins Y(t) ∈ ℕ.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of the three-stage model.

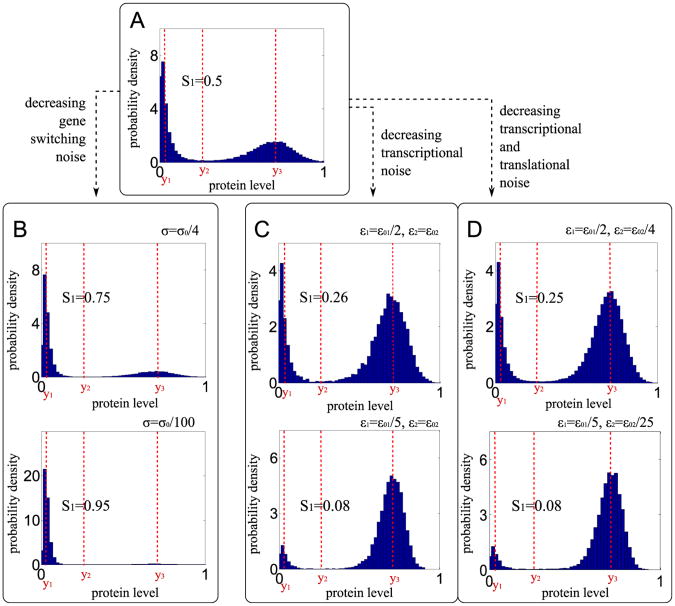

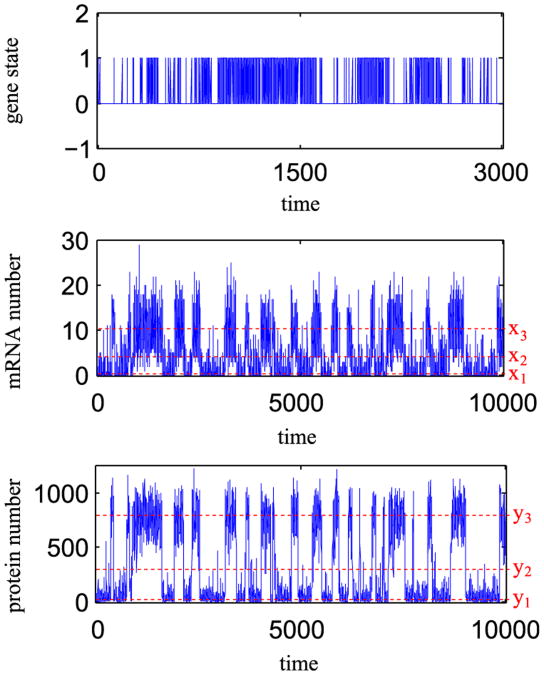

The assumed reaction rate constants are listed in Table 1. For a non-dimensional analysis we chose time units in which r2 = 1 (third column). Parameter values for prokaryotes and eukaryotes are calculated by assuming r2 = 10−4/s. As discussed in the Introduction, prokaryotes are characterized by large transcriptional and translational noise, while eukaryotes have larger gene switching noise. Therefore, in the example shown in Fig. 9, we assume for bacteria ε1 = ε01, ε2 = ε02, σ = σ0/100 and for eukaryotes ε1 = ε01/5, ε2 = ε02/25, σ = σ0, where ε01 = 1/15, ε02 = 1/75 and σ0 = 1/50. Parameters ε01, ε02 and σ0, will be referred to as default parameters. They are so chosen that the SPD corresponding to the Markov process is bimodal, and the probability mass is equally distributed between two basins of attraction, Fig. 9A. Fig. 10 shows stochastic simulation trajectory corresponding to the SPD shown in Fig. 9A.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

| Name | Symbol | Non-dimensional value | Valueforbacteria | Value for eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional noise default value | ε01 | 1/15 | ||

| Translational noise default value | ε02 | 1/75 | ||

| Gene switching noise default value | σ0 | 1/50 | ||

| Transcriptional noise | ε1 | ε01 | ε01/5 | |

| Translational noise | ε2 | ε02 | ε02/25 | |

| Gene switching noise | σ | σ0/100 | σ0 | |

| Protein degradation | r2 | 1 | 10−4/sa | 10−4/sb |

| mRNA degradation | r1 | 10r2 | 10−3/sc | 10−3/sd |

| Inducible gene activation | c2 | 4.8r2(ε1ε2)2/σ | 1.9 × 10−6/se | 1.2 × 10−12/sf |

| Basal gene activation | c0 | 0.027r2/σ | 0.0135/sg | 0.000135/sg |

| Gene inactivation | b0 | r2/σ | 0.5/sg | 0.005/sg |

| mRNA transcription | Q1 | r1/ε1 | 0.015/sh | 0.075/si |

| Protein translation | Q2 | r2/ε2 | 0.0075/sj | 0.1875/sk |

| mRNA number in | 0.03/ε1 | 0.5 | 2.28 | |

| Inactive (active) state | (0.64/ε1) | (10.6)l | (53.2)m | |

| Protein number in inactive (active) state | 0.03/ε1ε2 | 34.3 | 4290.1 | |

| (0.64/ε1ε2) | (798.4)n | (99799.4)o |

Most of bacterial proteins are very stable, with degradation rate constants: 1.4 × 10−5 −5.6 × 10−5/s (Jayapal et al., 2010). Some proteins have much higher degradation rates. E. coli RNase R has degradation rate constant of 10−3/s (in exponential phase) (Chen and Deutscher, 2010), factor σ32 has degradation rate constant of 10−2/s (in steady-state growth phase) (El-Samad et al., 2005).

Mammals: protein degradation rate constants: 1.7 × 10−6 −1.7 × 10−3/s (Hargrove, 1993).

The vast majority of mRNAs in a bacterial cell are very unstable, having a half-life of about 3 min (decay rate constant 3 × 10−3/s) (Alberts et al., 2002). E. coli: mRNA half-lives span between 1 and 18 min (decay rate constants 10−2 − 6 × 10−4/s) (Bernstein et al., 2002).

The eukaryotic mRNAs are more stable than prokaryotic with half-lives exceeding 10 h (decay rate constant 2 × 10−5/s). However, many have half-lives are of order of 30 min (decay rate constant 3 × 10−4/s) or less (Alberts et al., 2002). Mammalian mRNA degradation rate constants: 1.7 × 10−5 −1.7 × 10−3/s (Hargrove, 1993).

For 1 μm3 cell volume (bacterial cell) c2 = 6.9/(μM2 × s).

For 2 × 103 μm3 cell volume (mammalian cell) c2 = 1.7/(μM2 × s).

For prokaryotes gene switching is faster than for eukaryotes (Blake et al., 2003). Slow gene switching in eukaryotes is causing large mRNA bursts (Raj et al., 2006). However, the transcriptional bursting was also observed in E. coli promoter (Golding et al., 2005).

For E. coli the maximal transcription rate constant: 0.84/s (Kennel and Riezman, 1977).

For eukaryotes the maximal transcription rate constant: 0.84/s (Kafatos, 1972).

Translation initiation intervals are specific for each mRNA (Laursen et al., 2005). E. coli: translation initiation rate constant may vary at least 1000-fold (Sampson et al., 1988); examples of translation initiation frequencies; β-galactosidase: 0.31/s (spacing between ribosomes: 110 nucleotides), galactoside acetyltransferase: 0.06/s (spacing between ribosomes: 580 nucleotides) (Kennel and Riezman, 1977); maximal peptide chain elongation rate: 20aa/s (Young and Bremer, 1976; Bremer et al., 1974); average peptide chain elongation rate: 12aa/s (Kennel and Riezman, 1977).

Translation rate constant for eukaryotes: 0.018–1.8/s (Cohen et al., 2009).

E. coli: average mRNA copy number: 10−4–5 molecules/cell (Taniguchi et al., 2010).

Mammals (mice): average mRNA copy number observed in natural transcriptomes: 0.5–5 × 104 molecules/cell (Mortazavi et al., 2008; Galau et al., 1977).

E. coli: average protein copy number: 10−1 −104 molecules/cell (Taniguchi et al., 2010).

Mammals: the maximal protein copy number: 108 molecules/cell (Sims and Allbritton, 2007). Most of yeast genes: 103−5 × 104 molecules/cell (Gygi et al., 1999).

Fig. 9.

The marginal SPD of the three-stage model for parameters from Table 1. S1 – mass fraction in the inactive state basin of attraction. Panel (A) shows almost “equimodal” SPD obtained in the case when ε01 = 1/150, ε02 = 1/75 and σ0 = 1/50. Panel (B) shows the SPD of the constant transcriptional and translational noise ε1 = ε01, and ε2 = ε02 and decreasing gene switching noise σ. Panel (C) shows the SPD for the constant gene switching noise σ = σ0, constant translational noise ε2 = ε02 and decreasing transcriptional noise ε1. Panel (D) shows the SPD for the constant gene switching noise σ = σ0 and decreasing transcriptional and translational noise parameters ε1 and ε2.

Fig. 10.

Three-stage model: Stochastic simulation trajectory for default noise parameters ε1 = ε01 = 1/150, ε2 = ε02 = 1/75 and σ = σ0 = 1/50. The corresponding SPD is shown in Fig. 9A. Time is given in units equal to the mean protein lifetime.

In the σ→0, ε1→0 and ε2→0 limit, the considered Markov process for X(t), Y(t) can by approximated by the system of two ordinary differential equations for scaled variables x(t) = ε1X(t), y(t) = ε1ε2Y(t):

| (31) |

| (32) |

In a relatively broad range of parameters the above system exhibits bistability. The stable steady states with high and low protein concentration will be referred to as active and inactive, respectively. For assumed parameters (Table 1) the three steady states are

Inactive: x1 = 0.03, y1 = 0.03;

Unstable: x2 = 0.26, y2 = 0.26;

Active: x3 = 0.71, y3 = 0.71.

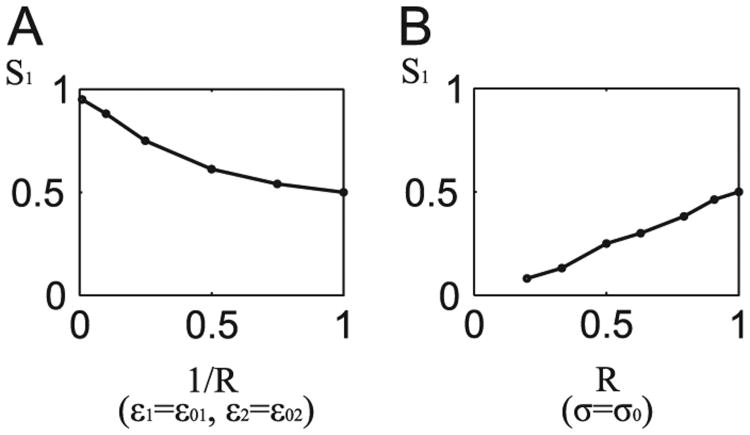

Let us note that stationary solutions of the system (31) and (32) depend only on c0/b0 and c2/b0, i.e. are independent to noise parameters σ, ε1, ε2. Noise parameters, however, influence the SPD. As shown in Fig. 9, the SPD for default noise parameters (Table 1) is bimodal with the probability mass equally distributed between two basins of attraction, Fig. 9A Decrease of the gene switching noise σ (with the transcriptional and translational noises kept constant) causes that the probability mass concentrates in the inactive state, Fig. 9B. In contrast, decrease of the transcriptional noise ε1 (with the gene switching and translational noises kept constant) causes that the probability mass concentrates in the active state, Fig. 9C. Decrease of the translational noise (simultaneously with transcriptional noise) does not significantly influence the SPD, Fig. 9D. Considering this observation, we focus on the normalized transcriptional to gene switching noise ratio, defined as R = (ε1 = ε01)/(σ/σ0). In Fig. 11 we analyze the mass fraction of the SPD in the basin of attraction of the inactive state, S1, as a function of R. Fraction S1 approaches unity as R−1 →0 (for fixed ε1 and ε2) and approaches zero as R→0 (for fixed σ). The results presented in Figs. 9 and 11 demonstrate that the type of dominating noise determines the most strongly attracting steady state. The small R (transcriptional to gene switching noise ratio), characteristic for eukaryotes, promotes gene activation. In turn, large R, characteristic for bacteria, promotes gene inactivation.

Fig. 11.

Mass fraction in the vicinity of the inactive state, S1, as a function of noise parameters ratio R = (ε1/ε01)/(σ/σ0). Panel (A) S1 plotted as a function of R−1 for constant ε1 = ε01 (and ε2 = ε02). Panel (B) S1 as a function of R for constant σ = σ0.

3. Conclusions

We considered two models of a self-regulating gene with underlying bistability. In the simplified two-stage model, the transcription and translation processes were lumped together, which allowed for the analytical approach. Next, we considered the three-stage model with three types of noise; transcriptional and translational – due to the limited number of mRNA and protein molecules, and the gene-switching noise – due to gene activation and inactivation. Analysis of both models demonstrated that the relative magnitudes of transcriptional and translational, and gene switching noise determine how the SPD is allocated between the two basins of attraction. We found that the low ratio of transcription to gene switching noise (R) promotes gene activation, while large R promotes gene inactivation.

Behavior of living cells is inherently associated with noise, which can be either perceived as an obstacle to accurate signal processing, or as a necessary factor introducing heterogeneity in cell populations. Noise enables cells to explore the state space, and allocates the cell population between the local optima – the epigenetic attractors. In this study we demonstrated that in the given epigenetic landscape, defined by the deterministic approximation, the relative occupancy of the attractors is controlled by the type of noise, even in the limit in which noise amplitude converges to zero. The theoretical consequence of our finding is that the prediction of the most strongly attracting steady state or global attractor in the classical Langevin approach, in which all noise sources are replaced by white noise, may not, in general, be correct. Observation that the most strongly attracting steady state, is controlled by relative contributions of the gene switching and transcriptional noise may be exploited in synthetic biology, which enables controlling the magnitudes of different noise sources in designed systems; see eg. Kierzek et al. (2001) and Ozbudak et al. (2002) where transcription and translation rates were independently modulated.

As already said the dominant noise is cell type-specific. The process of gene expression, analyzed in this study, involves at least three types of noise: gene-switching, transcriptional and translational. Eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells differ significantly in their gene expression noise characteristics. In eukaryotes, the most important source of noise are infrequent transitions between the on and off states (Raj et al., 2006; Becksei et al., 2005). In turn due to a large volume and correspondingly a large number of mRNA and proteins, the transcriptional and translational noises are relatively low. In the model the larger number of mRNA and protein was achieved by the increase of mRNA transcription and protein translational rate constants, which reflects the higher number of mRNA polymerases and ribosomes in eukaryotic cells. In prokaryotic cells gene activation and deactivation are thought to be very fast due to small volume, which implies easier contact and more frequent binding of transcription factors to the gene promoters. Thus, the gene switching noise in prokaryotes is typically low. Due to the small number of mRNA molecules and proteins, the gene expression noise in prokaryotic cells originates mostly from the transcription and translation events (Taniguchi et al., 2010). As a result eukaryotes, compared with prokaryotes, have a lower ratio of transcriptional to gene switching noise, which as demonstrated in this study promotes activation of autoregulatory genes.

In our study we concentrate on the gene expression noise, which is the most ubiquitous, but not always dominant source of noise in cell signaling. Earlier, we theoretically then experimentally demonstrated that at low dose TNF α stimulation, noise associated with stochastic receptor activation dominates over gene expression noise in NF-κB system (Lipniacki et al., 2007; Tay et al., 2010). As a result, at low dose stimulation, individual cell responses became highly asynchronous, with fraction of responding cells decreasing with the stimulation dose (Tay et al., 2010; Turner et al., 2010).

Noise characteristics are not only cell type-specific, but may also change during the cell cycle and development. This opens the possibility that relative occupancy of steady states may be actively controlled by noise. For example cell volume growth in G1 phase and DNA replication in S phase asynchronously modify the relative contributions of gene switching, transcriptional and translational noises. Much larger changes in noise magnitude and its characteristics accompany embryogenesis in fruit fly or frog. In the first case nuclear divisions (mitoses) begin following fertilization, but are not accompanied by division of cytoplasm (cytokinesis). Only after thirteen mitotic divisions, the approximately 5000 nuclei are partitioned into separate cells (Campos-Ortega, 1997). In the case of frog embryogenesis the huge egg is converted into a tadpole consisting of millions of much smaller cells containing the same amount of organic matter (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1994). One might speculate that changes in noise magnitude and characteristics add to the formation of morphogen gradients (changing relative stability of predefined steady states) initiating body segmentation and cell differentiation. Such mode of control, would require a more precise tuning of parameters than the simple tilting of the epigenetic landscape. However, it would have the advantage of keeping the epigenetic attractors (potentially the most plausible states) unchanged, with simultaneous modification of their relative occupancy.

Highlights.

We analyze stochastic bistable model of single autoregulatory gene.

Gene switching, transcriptional and translational noises are considered.

We show that the most stable attractor is determined by the type of noise.

The noise characteristics changes during cell cycle and development.

Noise type changes modify the relative occupancy of epigenetic attractors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Marek Kimmel for helpful comments. This study was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science grant TEAM/ 2009-3/6, Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education grant N N501 132936 and NSF/NIH grant No. R01-GM086885.

Contributor Information

Joanna Jaruszewicz, Email: jjarusz@ippt.gov.pl.

Pawel J. Zuk, Email: pzuk@ippt.gov.pl.

Tomasz Lipniacki, Email: tomek@rice.edu, tlipnia@ippt.gov.pl.

References

- Acar M, Becskei A, van Oudenaarden A. Enhancement of cellular memory by reducing stochastic transitions. Nature. 2005;435:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature03524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackers GK, Johnson AD, Shea MA. Quantitative model for gene regulation by lambda phage repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1129–1133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. fourth. Garland Science; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Becksei A, Kaufmann BB, van Oudenaarden A. Contributions of low molecule number and chromosomal positioning to stochastic gene expression. Nat Genet. 2005;37:937–944. doi: 10.1038/ng1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becskei A, Seraphin B, Serrano L. Positive feedback in eucaryotic gene networks: cell differentiation by graded to binary response conversion. EMBO J. 2001;20:2528–2535. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JA, Khodursky AB, Lin PH, Lin-Chao S, Cohen SN. Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coliat single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9697–9702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112318199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake WJ, Kaern M, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003;422:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrowski A. Degenerate convergence of semigroups related to a model of stochastic gene expression. Semigroup Forum. 2006;73:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrowski A, Lipniacki T, Pichór K, Rudnicki R. Asymptotic behavior of distributions of mRNA and protein levels in a model of stochastic gene expression. J Math Anal Appl. 2007;333:753–769. [Google Scholar]

- Bremer H, Hymes J, Dennis PP. Ribosomal RNA chain growth rate and RNA labelling patterns in Escherichia Coli. J Theor Biol. 1974;45:379–403. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(74)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega JA. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila Melanogaster. second. Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chang HH, Oh PY, Ingber DE, Huang S. Multistable and multistep dynamics in neutrophil differentiation. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Kaznessis YN, Hu WS. Tweaking biological switches through a better understanding of bistability behavior. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Deutscher MP. RNase R is a highly unstable protein regulated by growth phase and stress. RNA. 2010;16:667–672. doi: 10.1261/rna.1981010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JR, Trcek T, Shenoy SM, Singer RH. Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AA, Kalisky T, Mayo A, Geva-Zatorsky N, Danon T, Issaeva I, Kopito RB, Perzov N, Milo R, Sigal A, Alon U. Protein dynamics in individual human cells: experiment and theory. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Samad H, Kurata H, Doyle JC, Gross CA, Khammash M. Surviving heat shock: control strategies for robustness and performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2736–2741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigola D, Casanellas L, Sancho JM, Ibanes M. Asymmetric stochastic switching driven by intrinsic molecular noise. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galau GA, Klein WH, Britten RJ, H Davidson E. Significance of rare mRNA sequences in liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;179:584–599. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner CW. Handbook of Stochastic Methods for Physics, Chemistry and the Natural Sciences. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie DT. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J Phys Chem. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- Golding I, Paulsson J, Zawilski SM, Cox EC. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell. 2005;123:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1720–1730. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove JL. Microcomputer-assisted kinetic modeling of mammalian gene expression. FASEB J. 1993;7:1163–1170. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.12.8375615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseltine EL, Rawlings JB. Approximate simulation of coupled fast and slow reactions for stochastic chemical kinetics. J Chem Phys. 2002;117:6959–6969. [Google Scholar]

- Hasty J, Pradines J, Dolnik M, Collins JJ. Noise-based switches and amplifiers for gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2075–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040411297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hat B, Paszek P, Kimmel M, Piechor K, Lipniacki T. How the number of alleles influences gene expression. J Statist Phys. 2007;128:511–533. [Google Scholar]

- Hornos JEM, Schultz D, Innocentini GCP, Wang J, Walczak AM, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Self-regulating gene: an exact solution. Phys Rev E. 2005;72:051907. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayapal KP, Sui S, Philp RJ, Kok YJ, Yap MGS, Griffin TJ, Hu WS. Multitagging proteomic strategy to estimate protein turnover rates in dynamic Systems. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2087–2097. doi: 10.1021/pr9007738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafatos FC. The cocoonase zymogen cells of silk moths: model of terminal cell differentiation for specific protein synthesis. Curr Topics Dev Biol. 1972;7:125–191. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar R, Bose I. Positive feedback, stochasticity and genetic competence. Phys Biol. 2007;4:29–37. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/4/1/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennell D, Riezman H. Transcription and translation initiation frequencies of the Escherichia coli lac operon. J Mol Biol. 1977;114:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler TB, Elston TC. Stochasticity in transcriptional regulation: origins, consequences, and mathematical representations. Biophys J. 2001;81:3116–3136. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75949-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierzek AM, Zaim J, Zielenkiewicz P. The effect of transcription and translation initiation frequencies on the stochastic fluctuations in prokaryotic gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8165–8172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MSH. Stochastic model for gene induction. J Theor Biol. 1991;153:181–194. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussell E, Leibler S. Phenotypic diversity, and information in fluctuating environments. Science. 2005;309:2075–2078. doi: 10.1126/science.1114383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen BS, Soerensen HP, Mortensen KK, Sperling-Petersen HU. Initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:101–123. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.101-123.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipniacki T, Paszek P, Marciniak-Czochra A, Brasier AR, Kimmel M. Transcriptional stochasticity in gene expression. J Theor Biol. 2006;238:348–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipniacki T, Puszynski K, Paszek P, Brasier AR, Kimmel M. Single TNFα trimers mediating NF-κB activation: stochastic robustness of NF-κB signaling. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:376. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipniacki T, Hat B, Faeder JR, Hlavacek WS. Stochastic effects and bistability in T cell receptor signaling. J Theor Biol. 2008;254:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshtat A, Loinger A, Balaban NQ, Biham O. Genetic toggle switch without cooperative binding. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:188101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.188101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Lago TT, Stelling J. Counter-intuitive stochastic behavior of simple gene circuits with negative feedback. Biophys J. 2010;98:1742–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams HH, Arkin A. Stochastic mechanisms in gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miekisz J. Equilibrium selection in evolutionary? games with random matching of players. J Theor Biol. 2005;232:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevozhay D, Adams RM, Van Itallie E, Bennett MR, Balazsi G. Mapping the environmental fitness landscape of a synthetic gene circuit. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) Garland Publishing Inc; New York, London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ochab-Marcinek A, Tabaka M. Bimodal gene expression in noncooperative regulatory systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22096–22101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008965107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, Oudenaarden A. Regulation of noise in the expression of a single gene. Nat Genet. 2002;31:69–73. doi: 10.1038/ng869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Lim HN, Shraiman BI, Oudenaarden A. Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature. 2004;427:737–740. doi: 10.1038/nature02298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. A Genetic Switch: Phage Lambda Revisited. 3rd. Cold Harbor Spring Laboratory Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Puszynski K, Hat B, Lipniacki T. Oscillations and bistability in the stochastic model of p53 regulation. J Theor Biol. 2008;254:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Oudenaarden A. Single-molecule approaches to stochastic gene expression. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:255–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Peskin CS, Tranchina D, Vargas DY, Tyagi S. Stochastic mRNA synthesis in mammalian cells. PloS Biol. 2006;4:1707–1719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raser JM, O'Shea EK. Control of stochasticity in eukaryotic gene expression. Science. 2004;304:1811–1814. doi: 10.1126/science.1098641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld N, Elowitz M, Alon U. Negative autoregulation speeds the response times of transcription networks. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:785–793. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson LL, Hendrix RW, Huang WM, Casjens SR. Translation initiation controls the relative rates of expression of the bacteriophage λ late genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5439–5443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Understanding stochastic simulations of the smallest genetic networks. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:245102. doi: 10.1063/1.2741544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrezaei V, Swain PS. Analytical distributions for stochastic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17256–17261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal-Gaskins D, Grotewold E, Smith GD. The capacity for multistability in small gene regulatory networks. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:96. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims CE, Allbritton NL. Analysis of single mammalian cells on-chip. Lab Chip. 2007;7:423–440. doi: 10.1039/b615235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzak D, Lakhanpal A, Lebon L, Santat LA, Fontes ME, Anderson GA, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Elowitz MB. Cis-interactions between Notch and Delta generate mutually exclusive signalling states. Nature. 2010;465:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain PS, Elowitz MB, Siggia ED. Intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to stochasticity in gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12795–12800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162041399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS. Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science. 2010;329:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1188308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S, Hughey J, Lee T, Lipniacki T, Quake SR, Covert MW. Single-cell NF-κ B dynamics reveal digital activation and analogue information processing. Nature. 2010;466:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature09145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thattai M, Oudenaarden A. Intrinsic noise in gene regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8614–8619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151588598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DA, Paszek P, Woodcock DJ, Nelson DE, Horton CA, Wang Y, Spiller DG, Rand DA, White MRH, Harper CV. Physiological levels of TNF α stimulation induce stochastic dynamics of NF-κ B responses in single living cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2834–2843. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen NG. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. 3rd. Elsevier Science & Technology Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van Sinderen D, Vemnema G. comK acts as an autoregulatory control switch in the signal transduction route to competence in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5762–5770. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5762-5770.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellela M, Qian H. Stochastic dynamics and non-equilibrium thermodynamics of a bistable chemical system: the Schloegl model revisited. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:925–940. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak AM, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Absolute rate theories of epigenetic stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18926–18931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509547102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Bremer H. Polypeptide-chain-elongation rate in Escherichia coli B/r as a function of growth rate. Biochem J. 1976;160:185–194. doi: 10.1042/bj1600185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk PJ, Kochanczyk M, Jaruszewicz J, Bednorz W, Lipniacki T. Dynamics of a stochastic spatially extended system predicted by comparing deterministic and stochastic attractors of the corresponding birth death process. Phys Biol. 2012;9:055002. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/5/055002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]