Abstract

The genomic era is changing the understanding of cancer, although translation of the vast amount of data available into decision-making algorithms is far from reality. Molecular profiling of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the first cause of death among cirrhotic patients and a fast growing malignancy in Western countries, is enabling to propose novel approaches to disease diagnosis and management. Most HCC arise on a cirrhotic liver, and predictably, an accurate genomic characterization will allow the identification of pro-carcinogenic signals amenable for selective target within chemopreventive strategies. Molecular diagnosis is currently feasible for small tumors, but it has not yet been adopted by scientific guidelines. Molecular treatment is a reality after the unprecedented survival benefits obtained by sorafenib in patients at advanced stages. Genomic information from tumor and non-tumoral tissue will aid prognosis prediction, and facilitate the identification of oncogene addiction loops, providing the opportunity to a more personalized medicine.

Keywords: Liver cancer, genomics, personalized medicine, targeted therapy, genomics

OVERVIEW

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of death among cirrhotic patients, and with 600,000 deaths per year, it is the 3rd cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide1, 2. HCC ranks 6th in terms of global incidence, showing a steady increase in Western countries, mainly due to an increment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the last decades3. Currently, only one third of newly diagnosed HCC patients will be eligible for potential curative therapies4.

Unlike other cancers, HCC usually arises on a previously damaged organ, being liver cirrhosis the underlying disease in more than 80% of cases. This fact, added to the number of different etiologies responsible for liver damage (e.g. viral hepatitis, alcohol, iron overload and other causes of cirrhosis, etc.), warrants high molecular variability. Surveillance programs in cirrhotic patients have facilitated HCC diagnosis at earlier stages5. However, the development of effective chemopreventive strategies in this population is hindered by the lack of a reliable understanding of the genomic sequence of events occurring in this premalignant milieu.

The unprecedented results of a recently published phase III clinical trial show that sorafenib, a BRAF/VEGFR/PDGFR kinase inhibitor, significantly improves survival and time to progression in patients with advanced HCC6. This trial demonstrates the benefit of targeted therapies in HCC, highlighting the importance of oncogene addiction discovery in this malignancy. Molecular combination therapies are currently tested blocking the main pathways involved in HCC pathogenesis, such as mTOR signaling, c-MET signaling, IGF signaling and FGF signaling, among others. Current genomic research, however, has underscored the implication of additional pathways, particularly Wnt signaling, as drivers of proliferation. This review will focus on the diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic impact of genomics in HCC, and will provide some insight into future challenges of molecular medicine applied to this malignancy.

GENOMIC ASSESSMENT OF RISK: MOLECULAR EPIDEMIOLOGY

The current understanding of the epidemiology of HCC defines chronic infection due to HCV or HBV, cirrhosis, male gender and some mutants or genotype variants of HCV and HBV as the main predisposing factors for development of this cancer. HBV-related factors such as HBeAg positivity, high viral load, genotype C and HBV mutants have shown to be independent predictors of HCC development7, 8. Similarly, HCV genotype 1b is claimed to increase the risk of HCC development in a recent meta-analysis9. Aside of these clinical and virological variables, recent molecular data is emerging pointing germ-line DNA alterations and specific molecular traits in the pre-neoplastic cirrhotic tissue as important factors in the identification of at-risk populations.

The rapid advancement of cancer genomics has enabled the identification of mutations in germ-line DNA that define patients at high risk of developing cancer. This is the case for mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and increased risk of breast or ovarian cancer10, or in genes involved in DNA mismatch repair and hereditary colon cancer11. Recent genome-wide association studies and meta-analysis leaded by an International Consortium including thousands of patients provided robust genomic data supporting the role of genetic variants of BMP4, CDH1, RHPN2 and EIF3H contributing to the risk of colon cancer12, 13.

Data currently available to define at-risk populations of HCC on the basis of molecular analysis of polymorphisms lacks of the standards required in high quality investigations, such as large sample size, biological plausibility and independent validation14. For instance, SNPs and haplotypes located in the SCBY14, CRHR2, and GFRA1 genes were identified in a case-control study in patients with chronic HCV infection, but thorough external validation is required15. In order to overcome heterogeneity between studies and other methodological limitations, meta-analytic approaches and multivariate analysis including key clinical variables should be considered instrumental to provide reliable conclusions16. In HCC, a recent meta-analysis evaluated the effect of polymorphisms in genes encoding isoenzymes involved in cellular detoxification and risk of HCC. Among 15 studies identified, the authors concluded that carriers of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotype might have a small excess of HCC17, but again further studies are needed to confirm these results.

More revealing data was reported in a recent case-control study that found a significant association between an epidermal growth factor (EGF) gene polymorphism and the risk of HCC18. In this study, authors found a 4-fold odd of developing this cancer in cirrhotic patients with the G/G genotype for the EGF gene. These data were further validated in an independent cohort obtaining similar results. Interestingly, the G/G genotype was strikingly correlated with higher levels of EGF messenger both in vitro and in patient’s serum, increasing the biological plausibility of the hypothesis that links EGF to risk of HCC development. This hypothesis is supported by other confirmatory data. First, a recent study identified a gene signature from the cirrhotic tissue able to predict survival and late recurrence (> 2 years) in patients with HCC treated with surgical resection19. Notably, EGF was ranked among the top up-regulated genes in the poor-survival signature. Second, there is evidence correlating EGF over-expression in overt HCC, and identifying signals of anti-neoplastic effect of selective EGF receptor blockade in experimental models as well as in early phase clinical trials20, 21. Finally, using a carcinogen-induced rat model of HCC, gefintinib (an EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor) was able to decrease tumor incidence when compared to placebo22. All these data points EGF signaling as a potential target for chemoprevention in human HCC.

Further genome-wide association studies would be required for the identification of germ-line DNA alterations related with HCC development. In addition, specific gene signatures defining high risk of HCC development in cirrhotic patients are currently developed and tested. All this information would clarify the scenario for modern definition of at-risk populations, which will represent the main targets for chemopreventive drug assessment.

MOLECULAR DIAGNOSIS

In the past, HCC was considered a neoplasm with dismal outcome because almost all cases were diagnosed at terminal stages. During the last two decades there has been a switch in the detection and characterization of early HCC, as a result of the wide implementation of surveillance programs in Japan and the West and the application of cutting-edge imaging techniques5. The diagnostic algorithm proposed by the American Association for the Study of the Liver, which has been externally validated23, allows a confidential non-invasive diagnosis of most HCCs above 2 cm, and of one third of tumors less than 2 cm in size in cirrhotic patients5. If imaging-based diagnosis is not feasible, biopsy should be obtained, although the diagnostic accuracy of biopsy in small tumors is flawed by a false negative rate of 30–50%. The pathological resemblance between dysplastic nodules and well-differentiated HCC makes pathological confirmation difficult, even among expert hepatopathologists24. From a cost-benefit perspective the accurate diagnosis of small tumors < 2cm is critical because aggressive treatments, such as surgical resection or local ablation25 need to be applied in cancer, as opposed to the strategy of tight ultrasound-based follow-up recommended for dysplastic nodules, since only one third of them will acquire the malignant phenotype. Regrettably, the main serum tumor markers, such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP (AFP-L3), des-gamma carboxyprothrombin (DCP) and glypican-3 (GPC3)26, showed suboptimal results when tested in the surveillance and early detection mode.

Genome-wide gene expression microarray and quantitative real time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) studies have attempted to identify a molecular diagnosis of HCC. An extensive review of different genomic strategies leading to gene discovery is reviewed elsewhere27. Initially, using high-throughput qRT-PCR in a training-validation scheme, a study conducted in 128 human samples described a 13-gene signature able to confidently identify HCC lesions with high diagnostic accuracy28. Soon after, the application of microarray technologies allowed the detection of 120 genes able to discriminate dysplastic nodules and HCC in HBV patients29. Similarly, but restricted to HCV-related HCC, a 3-gene signature, including GPC3, LYVE1 and survivin, has been proposed as an accurate molecular tool (>80% accuracy) to discriminate dysplatic nodules and small HCC < 2cm in size30. The performance of this signature was externally validated in a different set of samples, and internally validated using a different genomic platform (i.e. oligonucleotide microarray31).

The diagnostic performance of some markers of early HCC identified by genomic studies has been prospectively assessed by immunohistochemistry. A promising marker is GPC3, that shows a sensitivity ranging 68–72% and a specificity superior to 92%37, 39, 40. Similarly, combination of different protein markers -HSP70, GPC3 and GS- in 105 hepatocellular nodules revealed appealing performance (sensitivity and specificity of 72% and 100%, respectively)40, which was afterwards validated in a larger series41. Despite all these advances in molecular diagnosis of HCC, not a single biomarker has been adopted in the standard diagnostic algorithms. Albeit their complex design requirements (i.e. large amount of small HCC, external validation, easy detection in clinical routine), the inclusion of a molecular diagnosis in guidelines of management is expected in the medium term.

GENOME-WIDE PROGNOSIS PREDICTION: INTEGRATION WITH CLINICAL SYSTEMS

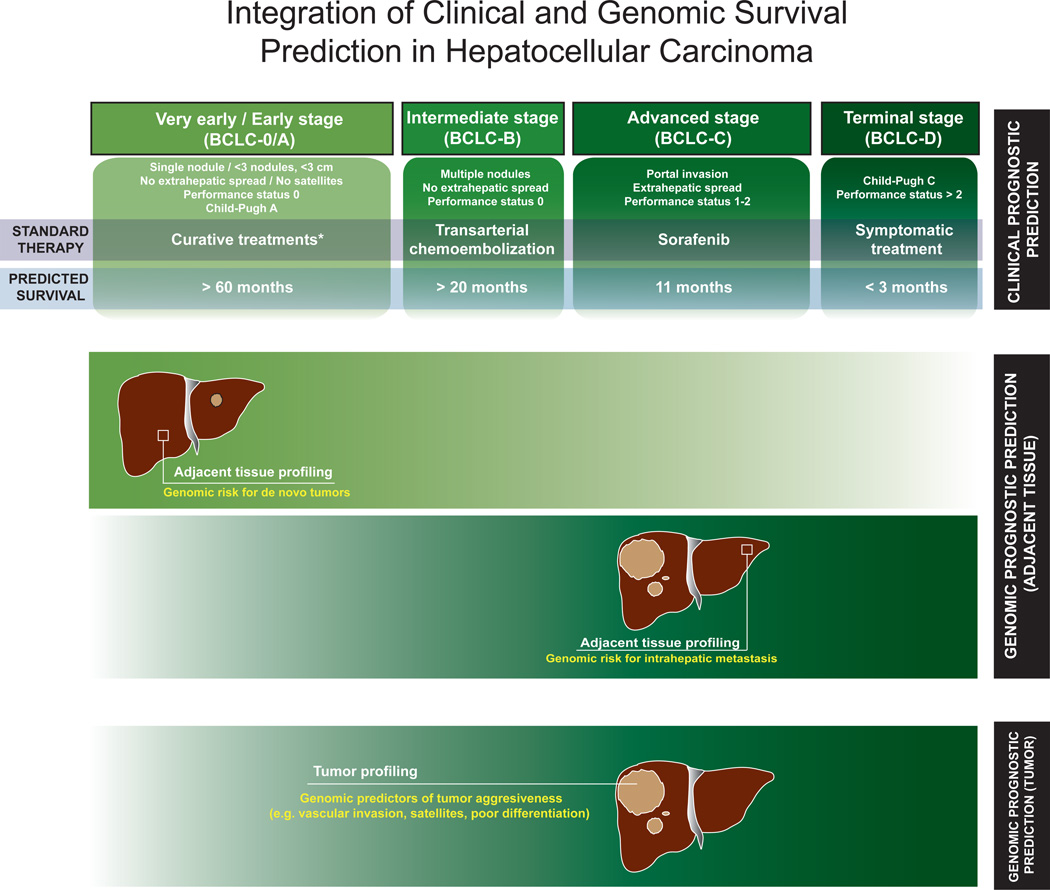

Cancer classification is aimed to establish prognosis, select the adequate treatment for the best candidates, and aid researchers to design clinical trials with comparable criteria. Staging systems are currently available in HCC, but no molecular data has been incorporated so far. In principle, these systems should incorporate variables related to tumor burden, liver function and symptoms. The Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging and treatment algorithm has been widely endorsed by guidelines of design of trials and clinical management4, 5, 32 (Figure 1). Briefly, patients are allocated for a specific therapy based on tumor burden (i.e. size and number of nodules, presence of satellites or extrahepatic spread), liver function (i.e. bilirubin, portal hypertension, Child-Pugh classification) and symptoms (i.e. ECOG-Performance status test). Patients at early stages (Stage 0-A) can achieve long median survival rates (> 60 months) if treated with potentially curative therapies as surgical resection, liver transplantation or percutaneous ablation. Patients at intermediate stage (Stage B) can improve survival from median 16 months of natural history to 20 months following chemoembolization. Patients at advanced stage (Stage C) can improve survival with sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that expanded median survival from 7.9 months to 10.7 months, establishing a new standard of care6. Among other systems, TNM is hampered by the need of information on microscopic vascular invasion33, only available in 20% of tumors undergoing surgical treatment. Other scores need to be further validated and do not provide a therapeutic algorithm (e.g. Japan Integrated Staging34, CLIP score35).

Figure 1.

Prognosis prediction in HCC will likely depend on 2 factors: 1. Clinical staging systems capturing tumor status, liver functional status and health condition). 2. Genomic data capturing gene profiles from tumor and non-tumoral cirrhotic tissue. Clinical systems (e.g. BCLC) offer a reliable framework to accurately predict prognosis in most patients. In addition, genomic profiling of the tumor and the surrounding tissue will complement clinical data to decrease misclassification rates. However, the relative importance of each component will depend on the stage of the disease. The top panel summarizes the different stages, therapy, and predicted survival in HCC according to BCLC staging system. The lower panels show the relative weight for survival prediction of genomic data from adjacent and tumoral tissue. Basically, in patients with very early HCC treated with surgical resection, survival is determined by risk of developing a de novo HCC, and this is genetically encoded in the surrounding tissue19. As cancer progresses, genomic data from de tumor becomes more informative in terms of survival prediction. This is due to the fact that several pathological features related to patient survival (e.g. vascular invasion, satellites, poor differentiation) are encoded in the tumor47. In these stages, patient survival will no longer depend so stringently on the risk for developing a de novo HCC, since the risk of death is more related to local disease and distant progression. Interestingly, local progression of the disease (i.e. intrahepatic metastasis51) in advanced stages is genetically encoded in the adjacent tissue.

Molecular biomarkers can have outcome implications, either as prognostic variables or as predictors of treatment response. Few cancer classifications involve these parameters. Such is the case of breast cancer, where Her2/nu status discriminates subgroups of patients with different outcome and treatment response to trastuzumab36. Similarly, EGFR mutational status in non-small cell lung cancer identifies responders to erlotinib37, and wild-type KRAS in colon cancer recognizes responders to cetuximab38. To some extent, patient’s molecular prognosis is determined by the identification of oncogenic loops and their susceptibility to ad hoc blockade therapy. Albeit clinically relevant, no clear oncogenic addiction loops reporting response to targeted therapies have been described in HCC, and the attempts to molecularly classify HCC patients have been based upon unbiased whole-genome approaches39.

The unprecedented high-throughput capacity of newly developed genomic platforms favors the assumption that genome-wide approaches could help in the identification of the molecular determinants of this disease. Initial experiences in leukemias and breast cancer clearly demonstrated the predictive power of applying microarray technologies40, but the molecular complexity of HCC was beyond the initial predictions. Unsupervised clustering of microarray data obtained from human HCC samples identified diverse groups of patients according to their similarities in gene expression. Integrative analysis with other genomic parameters (i.e. DNA copy number changes, point mutations, activation of signaling pathways) outlined at least two clear-cut groups of HCC characterized by either activation of the WNT signaling pathway or by over-expression of genes implicated in cell cycling and proliferation39. The fact that different research teams identified both classes, using different genomic platforms after studying a wide clinical range of human HCC guaranteed their robustness41–43.

Subsequent analysis suggested that the molecular cluster characterized by proliferation signals was rather polymorphic. Within this class, other signatures were obtained after supervised analysis of different signaling cascades such as MET44 and TGFB45. In addition, genomic data mining integrating information from tumors and cells from other species (i.e. Comparative Functional Genomics46), identified a group of HCC with significant similarities with a expression pattern found in rat fetal hepatoblasts47, suggesting that tumors holding this hepatoblast signature could be derived from progenitor cells. Consequently, microarray data could not only be used for patient classification, but also to determine cellular lineages within tumors. Upon reemergence of the cancer stem cell theory48, another study also addressed the cell of origin issue in HCC by means of gene expression data analysis. In this case, authors identify a gene signature enriched in genes functionally linked to organ development (i.e. EpCAM signature49, 50).

Apart from obtaining new biological and lineage insights in HCC, all these studies also aimed to correlate molecular signatures with patient outcome. Basically, those signatures included in the proliferation class were significantly correlated with patient worse prognosis (Table 1). However, the lack of external replication of any of these prognostic signatures is a major drawback for its clinical translation. Also, there are some concerns regarding the low prognostic relevance of some of the clinical variables included in the multivariate analysis reported in most of these studies.

Table 1.

Relevant studies predicting outcome based on whole-genome expression data.

| Patients | Predominant etiology of cirrhosis |

Endpoint | Signature associated with poor clinical outcome |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic information from tumor | ||||

| Ye et al.53, Yamashita T et al.49, 50 | 278 | HBV (100%) | Intrahepatic metastasis, overall survival | EpCAM+ |

| Lee JS et al.43, 47, Kaposi-Novak P et al.44, Coulouarn C et al.45 | 138 | HBV (57%) | Overall survival | Class A43 / Hepatoblast47 / Met+44 / TGFB-Late45 |

| Chiang et al.42, Villanueva et al.52 | 232 | HCV (61%) | Tumor recurrence | Proliferation |

| Genomic information from cirrhosis | ||||

| Budhu A et al.51 | 210 | HBV (96%) | Intrahepatic metastasis | Metastasis inclined microenvironment |

| Hoshida Y et al.19 | 307 | HCV (53%) | Overall survival, tumor late recurrence (>2 years) | Poor prognosis signature |

Gene expression data obtained from adjacent non-tumoral liver tissue has also proved extremely useful for patient classification. Indeed, two seminal studies have clearly demonstrated the importance of the microenvironment for accurate prognosis prediction in HCC. The first study focused on HBV patients with advanced tumors treated with surgical resection, and defined a signature to develop early recurrence51. The second study analyzed mostly HCV-related early HCC patients treated with surgical resection, and identified a gene signature able to predict overall survival19. Essentially, the signature was capturing biological signals related to high risk of developing a late recurrence (i.e. de novo tumors in a cirrhotic liver). Notably, both signatures are complementary and reflect different dimensions of the so-called “field effect”: the first is a genomic portrait of a metastatic-favoring milieu, while the second is more related to high risk for HCC development. (Table 142–45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 53).

We speculate that prognosis prediction in HCC pivots in 3 pillars: (1) clinical parameters, as those described in the BCLC algorithm, (2) genomic data obtained from the tumor, and (3) genomic data from the adjacent non-tumoral tissue. More importantly, the strength of each prognostic component must be weighted according to the clinical stage of the disease, as illustrated in Figure 1. We estimate that gene alterations of adjacent non-tumoral tissue are more relevant in early cases, whereas those of the tumor are more important in advanced cases. Outcome of early HCC properly treated by resection or local ablation would rather be determined by late events, particularly risk of late recurrence (de novo tumors), which might outweigh the risk of true metastases. Genomic predictors of de novo HCC are coded within cirrhotic tissue, the preneoplastic milieu responsible for HCC development in the first place19

MOLECULAR THERAPIES: BEYOND SORAFENIB

Molecular targeted therapies represent the dawn of a new era in the management of cancer patients. More than ten molecular therapies have been approved in oncology as a result of survival improvements in patients with breast, colorectal, non-small cell lung, renal and head and neck cancer. This is now also the case for HCC. The recent positive results of sorafenib, a multi-target therapy with blockade activity against RAS, VEGFR and PDGFR, represent a breakthrough in the management of patients with HCC6. The unquestionable survival benefits obtained in a phase III clinical trial had several remarkable consequences. First, sorafenib represents the first systemic therapy effective in advanced cases ever, after 30 years of research. Second, it is the proof of concept that a molecular therapy is effective in this otherwise chemo-resistant cancer. Third, the magnitude of survival benefit measured by the hazard ratio (i.e. hazard ratio of 0.69) is similar to that obtained with other consolidated molecular therapies in oncology. As a consequence, this therapy has been adopted in clinical guidelines as the standard of care in patients with advanced and disseminated disease32. The advent of sorafenib constitutes a first step in the complex management of this disease, which should be complemented with other molecular approaches. Even thought our understanding of HCC genomics is still elementary, there is certain evidence that suggests the implication of several signaling cascades in the molecular pathogenesis of HCC, including EGFR-RAS-MAPKK pathway, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), mTOR, MET, FGF, Wnt-βCatenin, and angiogenesis (VEGF, PDGFR)54. Other pathways involved in hepatocarcinogenesis such as Jak-STAT, TGF-β and Hedgehog need further attention to define their relevance and potential therapeutic interest.

A plethora of targeted therapies have been tested in preclinical models of HCC aiming to establish the proof-of-principal for testing novel agents in humans. A comprehensive analysis of the current targeted therapies tested within clinical trials and their mechanism of action has been reviewed elsewhere (see review Llovet et al55). Preliminary results in early trials provide some insights on the anti-tumoral effect of drugs blocking EGFR, VEGF/PDGFR and mTOR signaling or combinations thereof (Table 26, 20, 21, 56–62). Interpretations of most of these trials, however, is hampered by the lack of a common selection of the study population, for instance including patients with so called unresectable HCC, as opposed to the well-characterized subclasses BCLC stage B and C63. Current research is now aiming to combine molecular therapies, mainly sorafenib with EGFR inhibitors (erlotinib), mTOR inhibitors (everolimus), c-MET inhibitors or IGF inhibitors. The toxicity profile will represent the main challenge of such combinations. In addition, alterantive anti-angiogenic therapies are heavily tested (bevacizumab, sunitinib and brivanib). Future research is expected to identify new compounds to block important undruggable pathways, such as Wnt signaling, and to identify new oncogenes as targets for therapies through novel high-throughput technologies.

Table 2.

Phase II and III trials published suing molecular targeted therapies in HCC.

| Patients | Treatment | Target | Response rate |

Survival in the treatment arm (months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase III | |||||

| Llovet JM6 | 602 | Sorafenib | BRAF/MEK/ERK, VEGFR, PDGFR | 2.3% | 10.7 |

| Cheng AL58 | 271 | Sorafenib | BRAF/MEK/ERK, VEGFR, PDGFR | 3.30% | 6.5 |

| Phase II | |||||

| Abou-Alfa GK56 | 137 | Sorafenib | BRAF/MEK/ERK, VEGFR, PDGFR | 8% | 9.2 |

| Yau T62 | 51 | Sorafenib | BRAF/MEK/ERK, VEGFR, PDGFR | 8% | 5 |

| Siegel AB60 | 46 | Bevacizumab | VEGFR | 13% | 12.4 |

| Thomas MB21 | 40 | Erlotinib + bevacizumab | EGFR, VEGF | 25% | 15.75 |

| Thomas MB61 | 40 | Erlotinib | EGFR | 0% | 10.75 |

| Philip PA20 | 38 | Erlotinib | EGFR | 9% | 13 |

| Ramanathan RK59 | 57 | Lapatinib | EGFR, Her2/neu | 5% | 6.2 |

| Asnacios A57 | 45 | GEMOX + Cetuximab | EGFR | 20% | 9.5 |

Trial design has also changed due to the results of the sorafenib phase III study. Recent guidelines have established a new frame for the design of clinical trials in HCC32. Survival remains the main endpoint to measure effectiveness in phase III studies, but randomized phase II trials with a time to progression endpoint are proposed as pivotal for capturing benefits from novel drugs. Due to the heterogeneity of target populations, it was estimated that an internal control arm within randomized phase II studies would guarantee a more accurate identification of signals of efficacy. In addition, the recent survival benefits of sorafenib were not followed by a parallel impact in tumor shrinkage (objective responses <3%), a phenomena also observed with other molecular therapies (e.g. termsirolimus in renal cancer, bevacizumab in liver metastases of colorectal cancer). These drugs are capable to delay tumor progression in such a manner that impact survival outcomes. Thus, a time-to-event end point as time to progression was proposed as more appropriated.

HCC is highly heterogenic from a genomic perspective, and therefore, it is assumable that several drivers (i.e. oncogene addiction loops) will be responsible of proliferation of different tumor subclasses. The proper identification and characterization of new targets in experimental models of HCC will facilitate generation of mechanistic hypothesis and description of potential biomarkers of response to novel drugs. Ultimately, the translation of these results to clinical trials will allow tailoring therapies based on the molecular background of the tumor itself, and the adjacent non-tumoral tissue, in a more personalized approach.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Augusto Villanueva is a recipient of a Sheila Sherlock (European Association for the Study of the Liver) fellowship. Beatriz Mínguez is the recipient of a grant from Programa de Estancias de Movilidad Postdoctoral en el Extranjero incluidas las ayudas MICINN/Fulbright (EX 2008-0632). Alejandro Forner is partially supported by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI 05/645). Maria Reig is funded by a grant of the BBVA foundation. Josep M. Llovet has grants from National Institute of Health - NIDDK 1R01DK076986-01, National Institute of Health (Spain) grant I+D Program (SAF-2007-61898) and Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation.

Contributor Information

Augusto Villanueva, Email: augusto.villanueva@ciberehd.org.

Beatriz Minguez, Email: beatriz.minguez@mssm.edu.

Alejandro Forner, Email: aforner@clinic.ub.es.

Maria Reig, Email: mreig1@clinic.ub.es.

Josep M. Llovet, Email: josep.llovet@mssm.edu.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus genotype and mutants: risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1121–1123. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang HI, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, et al. Associations between hepatitis B virus genotype and mutants and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1134–1143. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raimondi S, Bruno S, Mondelli MU, Maisonneuve P. Hepatitis C virus genotype 1b as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma development: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1142–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marra G, Boland CR. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: the syndrome, the genes, and historical perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1114–1125. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.15.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houlston RS, Webb E, Broderick P, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies four new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1426–1435. doi: 10.1038/ng.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlinson IP, Webb E, Carvajal-Carmona L, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies colorectal cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 10p14 and 8q23.3. Nat Genet. 2008;40:623–630. doi: 10.1038/ng.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlman I, Eaves IA, Kosoy R, et al. Parameters for reliable results in genetic association studies in common disease. Nat Genet. 2002;30:149–150. doi: 10.1038/ng825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato N, Ji G, Wang Y, et al. Large-scale search of single nucleotide polymorphisms for hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility genes in patients with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;42:846–853. doi: 10.1002/hep.20860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White DL, Li D, Nurgalieva Z, El-Serag HB. Genetic variants of glutathione S-transferase as possible risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: a HuGE systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:377–389. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanabe KK, Lemoine A, Finkelstein DM, et al. Epidermal growth factor gene functional polymorphism and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Jama. 2008;299:53–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, et al. Phase II study of Erlotinib (OSI-774) in patients with advanced hepatocellular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6657–6663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas MB, Chadha R, Glover K, et al. Phase 2 study of erlotinib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:1059–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffer E, Housset C, Cacheux W, et al. Gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor, prevents hepatocellular carcinoma development in the rat liver with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:307–314. doi: 10.1002/hep.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forner A, Vilana R, Ayuso C, et al. Diagnosis of hepatic nodules 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis: Prospective validation of the noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:97–104. doi: 10.1002/hep.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojiro M, Roskams T. Early hepatocellular carcinoma and dysplastic nodules. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:133–142. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sala M, Llovet JM, Vilana R, et al. Initial response to percutaneous ablation predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2004;40:1352–1360. doi: 10.1002/hep.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marrero JA, Feng Z, Wang Y, et al. alpha-Fetoprotein, Des-gamma Carboxyprothrombin, and Lectin-Bound alpha-Fetoprotein in Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemmer E, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Molecular diagnosis of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: the potential of gene expression profiling. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:373–384. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paradis V, Bieche I, Dargere D, et al. Molecular profiling of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) using a large-scale real-time RT-PCR approach: determination of a molecular diagnostic index. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:733–741. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63700-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam SW, Park JY, Ramasamy A, et al. Molecular changes from dysplastic nodule to hepatocellular carcinoma through gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2005;42:809–818. doi: 10.1002/hep.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llovet JM, Chen Y, Wurmbach E, et al. A molecular signature to discriminate dysplastic nodules from early hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1758–1767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698–711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liver (including intrahepatic bile ducts) 6 ed. New York: Springler; [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudo M, Chung H, Haji S, et al. Validation of a new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: the JIS score compared with the CLIP score. Hepatology. 2004;40:1396–1405. doi: 10.1002/hep.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prospective validation of the CLIP score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators. Hepatology. 2000;31:840–845. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villanueva A, Toffanin S, Llovet JM. Linking molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma and personalized medicine: preliminary steps. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:444–453. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328302c9e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reynies A, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6779–6788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JS, Chu IS, Heo J, et al. Classification and prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2004;40:667–676. doi: 10.1002/hep.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaposi-Novak P, Lee JS, Gomez-Quiroz L, Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Met-regulated expression signature defines a subset of human hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1582–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI27236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Transforming growth factor-beta gene expression signature in mouse hepatocytes predicts clinical outcome in human cancer. Hepatology. 2008;47:2059–2067. doi: 10.1002/hep.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, et al. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, et al. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1451–1461. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, et al. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang D, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma with progenitor cell markers. Hepatology. 2008;48:361A–362A. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, et al. Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2003;9:416–423. doi: 10.1038/nm843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312–1327. doi: 10.1002/hep.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293–4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asnacios A, Fartoux L, Romano O, et al. Gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (GEMOX) combined with cetuximab in patients with progressive advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a multicenter phase 2 study. Cancer. 2008;112:2733–2739. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramanathan RK, Belani CP, Singh DA, et al. A phase II study of lapatinib in patients with advanced biliary tree and hepatocellular cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0927-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siegel AB, Cohen EI, Ocean A, et al. Phase II trial evaluating the clinical and biologic effects of bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2992–2998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas MB, Morris JS, Chadha R, et al. Phase II trial of the combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib in patients who have advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:843–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yau T, Chan P, Ng KK, et al. Phase 2 open-label study of single-agent sorafenib in treating advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatitis B-endemic Asian population: presence of lung metastasis predicts poor response. Cancer. 2009;115:428–436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, et al. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]