Abstract

Radiation treatment of head and neck cancers causes irreversible damage of the salivary glands (SG). Here, we introduce a preclinical mouse model for small-interfering RNA (siRNA)-based gene silencing to provide protection of SG from radiation-induced apoptosis. Novel, pH-responsive nanoparticles complexed with siRNAs were introduced into mouse submandibular glands (SMG) by retroductal injection to modulate gene expression in vivo. To validate this approach, we first targeted Nkcc1, an ion transporter that is essential for saliva secretion. Nkcc1 siRNA delivery resulted in efficient knockdown, as quantified at the mRNA and the protein levels, and the functional result of Nkcc1 knockdown phenocopied the severe decrease in saliva secretion, characteristic of the systemic Nkcc1 gene knockout. To establish a strategy to prevent apoptotic cell loss due to radiation damage, siRNAs targeting the proapoptotic Pkcδ gene were administered into SMG before ionizing radiation. Knockdown of Pkcδ not only reduced the number of apoptotic cells during the acute phase of radiation damage, but also markedly improved saliva secretion at 3 months in irradiated animals, indicating that this treatment confers protection from hyposalivation. These results demonstrate that nanoparticle delivery of siRNAs targeting a proapoptotic gene is a localized, nonviral, and effective means of conferring radioprotection to the SGs.

Introduction

A critical issue in the treatment of head and neck tumors is radioprotection of the salivary glands (SG). Therapeutic radiation, the standard treatment for patients with head and neck cancers, causes permanent and irreversible damage to the SGs, due to rapid apoptotic loss of the cells as a consequence of DNA damage. This extensive cell death results in chronic hyposalivation. Although improvements have been made in irradiation techniques, the treatment options for xerostomia are largely palliative and unsatisfactory.1 To develop improved radioprotection strategies for the SGs, we examined the therapeutic potential of small-interfering RNAs (siRNA) for target gene silencing. The application of RNA interference has progressed from preclinical in vivo tests to ongoing clinical trials for cancer, lung disease, and liver damage in humans.2,3

Targeted delivery of therapeutic agents into the SGs can conveniently be achieved through the main excretory duct. Retrograde injection methods provide direct access to the gland parenchyma, and have been utilized in gene therapy experiments.3,4 This approach (retroductal injection) is also routinely utilized as a noninvasive clinical procedure for diagnostic imaging. The SGs are surrounded by an encapsulating tissue layer which limits diffusion of the injected fluid.5 These advantages have led to active investigation into adapting gene therapy strategies to address pathological conditions of the SGs and upper gastrointestinal tract.6

The most critical aspect of gene therapy is the availability of a potent and safe carrier for therapeutic gene delivery. Adenoviral and adeno-associated viral vectors have been used for gene transfer into the SGs to treat disorders, such as Sjögren's syndrome and hyposalivation resulting from radiation damage.7,8 However, the viral vectors elicit strong immune responses in the SGs.7 siRNAs have been introduced into the SG either by conjugation with a receptor ligand of the recipient cell,9 or by increasing the porosity of the target cell membrane with microbubbles.10 However, a major limitation of these two methods is the low efficiency of intracellular siRNA delivery. In this study, we have investigated the therapeutic efficacy of modulating gene expression in irradiated SGs using nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery.

The successful delivery of siRNAs complexed with nanoparticles has been reported in several other tissues and organs, including the trachea, liver, prostate, and skin (reviewed in ref. 11). We have previously established that novel, pH-responsive nanoparticles efficiently delivered functional siRNAs into cultured SG cells.12 The nanoparticles, composed of diblock polymers that form cationic micelles, bind the negatively charged siRNAs electrostatically.13 Following endocytic uptake, the pH-responsive endosomolytic polymer promotes siRNA delivery to the cytoplasm.14 We demonstrated that targeting proapoptotic genes (Pkcδ or Bax) conferred radioprotection to SG cells in vitro.12 Moreover, the siRNA–nanoparticle complexes are degradable and noncytotoxic13,15 due to their amphiphilic properties in cultured cells.

To demonstrate the direct functional consequence of RNA interference knockdown in vivo, we first targeted expression of type 1 Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter (Nkcc1; encoded by the SLC12A2 gene) using nanocomplexed siRNA. Nkcc1 is critical for transepithelial Cl− transport, which drives saliva secretion in the parotid and submandibular glands (SMG).16 In mice homozygous for knockout of Nkcc1, saliva secretion is severely decreased. We demonstrate that nanoparticle delivery of siRNAs targeting Nkcc1 into the SMG effectively mimics the phenotype of Nkcc1−/− mice.

To further establish the therapeutic potential of siRNA–nanoparticle injections, we investigated their efficacy in the protection of SG cells from radiation-induced damage. Protein kinase C (PKC) δ plays a direct role in the apoptosis of acinar cells, both in vitro and in vivo.17,18 In fact, knockout of the Pkcδ gene acts to protect murine SGs against radiation-induced apoptosis.17 Here, we demonstrate that siRNA–nanoparticles targeting the proapoptotic mediator Pkcδ in SGs before radiation treatment protect the glands from radiation-induced damage and concomitant hyposalivation.

Results

In vivo administration of siRNA into mouse SMG

Retrograde injections were unilaterally performed through the main excretory duct of the SMG in BALB/c mice. The intraoral image (Figure 1a) shows retroductal injection of a permanent tissue dye, which was used to determine the optimal volume for injections (18–20 μl) and to confirm dye retention in the gland following injection (Supplementary Figure S1a). To demonstrate in vivo delivery of siRNA and monitor its distribution following retrograde injection, Cy3-labeled siRNA was used. SMG tissue was excised at 3, 6, 8 or 24 hours following siRNA injection. At 3 hours post-injection, Cy3-tagged siRNAs were internalized in the cytoplasm of duct cells via the endosomal pathway, as confirmed by partial colocalization with the early endosomal marker, EEA1 (Figure 1b). Based on the intensity of the fluorescent signal, the Cy3-tagged siRNA was delivered into the SMG most efficiently by the pH-responsive nanoparticles (Figure 1d,g), as compared with naked siRNA (Supplementary Figure S1b) or Lipofectamine-mediated Cy3-siRNA controls (Figure 1c,f). At 6 hours post-injection, the Cy3-fluorescent signal was concentrated in the acinar compartment as well (Figure 1e,h). To confirm cellular uptake, an acinar cell-specific marker, aquaporin 5 (AQP5), was used for colocalization (Supplementary Figure S1d). Cellular uptake of Cy3-siRNA by the SMG cells was also confirmed by flow cytometry after SMG cell isolation (Supplementary Figure S2); 24 hours after Cy3-tagged siRNA–nanoparticle complexes were injected, 38.3 (± 3%) of the total isolated SMG cells were found to be Cy3-positive.

Figure 1.

In vivo administration of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes into mouse submandibular gland. (a) Retroductal injection was performed through an ultra-thin, pre-made polyurethane tube, inserted into the orifice of the Wharton duct draining the left SMG (×30 original magnification). (b) Colocalization of the early endosomal antigen 1, EEA1 (green) with Cy3-tagged siRNA–nanoparticle complexes (red) in duct cells at 3 hours after injection (arrowheads). (c,f) Phase contrast and red fluorescent image of Lipofectamine-mediated transfection of Cy3-siRNA (red) in SMG at 8 hours post-injection. (d,g) Phase contrast and fluorescent images of nanoparticle-complexed Cy3-siRNA injected into SMG, at 8 hours post-injection. (e,h) Cy3-siRNA–nanoparticle complexes are detected in the acinar compartment (ac), as well as in duct cells (du), at 6 hours post-injection. For b, bar = 20 μm; for c,f, bar = 500 μm; for d,g, bar = 100 μm; for e,h, bar = 50 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

siRNAs mediate in vivo knockdown of Nkcc1 in mouse SMG

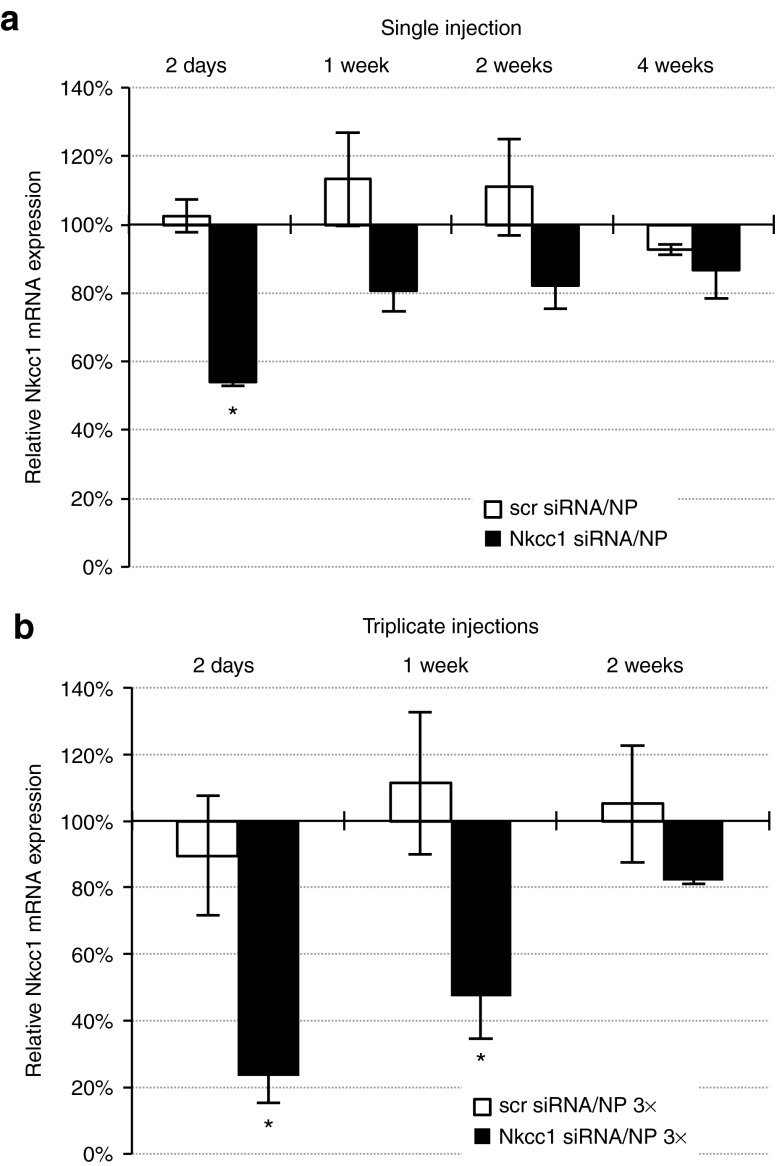

Having established the efficient delivery of siRNAs into the SMG using nanoparticles, we tested the ability of the siRNAs to achieve effective knockdown of Nkcc1 gene expression in vivo. siRNAs (SMARTpool of four functional siRNAs) targeting Nkcc1 were complexed with nanoparticles, and injected retrogradely into the SMG excretory duct of wild-type BALB/c mice. At specified time points after injection, Nkcc1 gene expression in SMG was measured and compared with untreated animals, to animals injected with scrambled (scr), non-targeting siRNAs, and to animals injected with Nkcc1-targeting siRNAs. At 2 days post-injection, a statistically significant (P = 0.007) decrease in Nkcc1 mRNA levels of 48.4 (± 3.7%) was measured in the Nkcc1 siRNA-injected group relative to Nkcc1+/− mice and to BALB/c+/+ (mRNA levels were equivalent in both genotypes and set at 100%) or to scrambled siRNA-injected controls (Figure 2a). After 1 and 2 weeks, Nkcc1 mRNA levels were still suppressed in Nkcc1 siRNA-injected animals, although the difference from controls was not significant (P values ranged from 0.482 to 0.988). However, triplicate injections (single injections on three consecutive days) resulted in robust Nkcc1 knockdown for 1 week (Figure 2b). At day 2 post-injection, following triplicate injections, Nkcc1 mRNA levels were decreased to 23.4 (± 8%) of the untreated controls. At 1 week post-injection, Nkcc1 mRNA expression remained suppressed at 47.2 (± 12.8%) of that in Nkcc1+/− mice. A similar, statistically significant decrease was found at day 2 (by 66%) and at 1 week (by 64%) in comparison to the scrambled siRNA-injected group.

Figure 2.

Retrograde injection of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes mediates in vivo knockdown of Nkcc1 gene expression in mouse SMG. Real-time quantitative PCR measurements of Nkcc1 mRNA expression were conducted at different time points after (a) single or (b) triplicate retrograde injections of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes. Quantification represents data in each sample group relative to mRNA levels determined from Nkcc1+/− littermates, which were set at 100% (all error bars represent SEM; n = 3–5; *P < 0.05) (scr siRNA, scrambled siRNA; NP, nanoparticles). siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

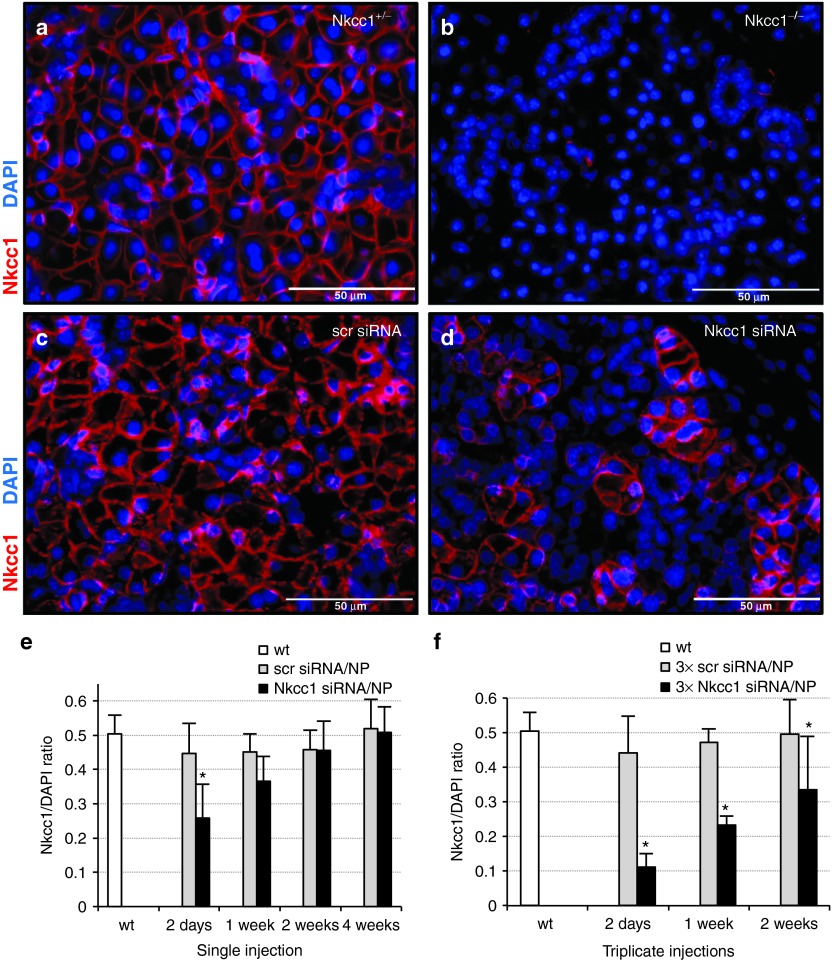

Immunohistochemistry was used to determine the efficiency of Nkcc1 protein knockdown in vivo. Paraffin sections of SMGs isolated at 2, 7, 14, and 28 days following single or triplicate siRNA injections were stained with an Nkcc1-specific antibody. In control sections of both Nkcc1+/− and wild-type BALB/c mice (data not shown), Nkcc1 is localized to the basolateral membranes of acinar cells (Figure 3a). As expected, sections from Nkcc1−/− showed a complete absence of antibody staining (Figure 3b). At day 2 following a single siRNA injection, Nkcc1 protein expression was significantly decreased in SMG sections by 43 (± 19%) (Figure 3d), compared to sections from animals injected with scrambled siRNA (Figure 3c). These results were quantified by selecting 10 random microscopic fields (330 × 430 μm) per section for digital capture using the Metamorph 7.7.10 imaging software (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Within each image, all DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-stained nuclei were counted. The ratio of Nkcc1-positive cells to the total number of DAPI-stained cells was calculated (ImageJ Basics software; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and expressed as a percentage (Figure 3e,f). By 2 weeks post-injection, Nkcc1 protein expression returned to endogenous levels (Figure 3e). In contrast, triplicate injections resulted in a decrease of 73% by day 2 post-injection, and a prolonged Nkcc1 protein knockdown of at least 32% for up to 2 weeks, in comparison to scrambled siRNA controls (Figure 3f).

Figure 3.

In vivo Nkcc1 protein expression is significantly decreased following nanoparticle-mediated delivery of siRNA. (a,b) Sections from control and Nkcc1−/− SMGs stained with antibody to Nkcc1. (c,d) SMG sections isolated at 2 days post-injection from mice following a single injection of (c) scrambled or (d) Nkcc1 siRNA, respectively. (e) Measure of Nkcc1 protein knockdown over time as a result of a single injection of siRNA complexed with nanoparticles, expressed as the ratio of Nkcc1-positive cells to total cell number. (f) Measure of Nkcc1 protein knockdown over time following triplicate nanoparticle siRNA injections, expressed as a ratio of Nkcc1-positive cells to total cell number. Calculations for e and f were determined from 10 randomly selected areas (330 × 430 μm) on sections from three animals per sample group. (Means ± SEM; *P < 0.05) (scr siRNA, scrambled siRNA; NP, nanoparticles; 3×, triplicate). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland; wt, wild-type.

Retrograde injection of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes results in decreased saliva secretion

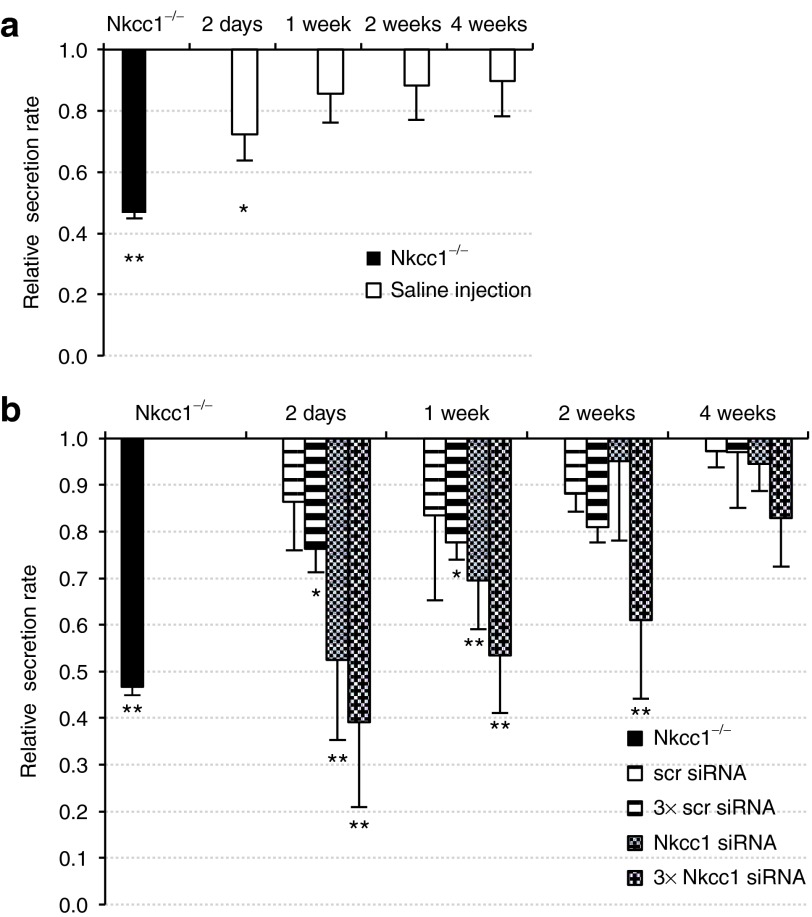

To test the effect of siRNA–nanoparticle injections on SMG function, we analyzed saliva output. Salivary flow was stimulated with pilocarpine and saliva was collected directly from cannulated SMGs. Saliva flow rates were normalized to those of untreated control animals (BALB/c mice). We observed that a single injection of scrambled siRNA–nanoparticle complexes resulted in a general inhibition of saliva secretion by 14 (± 6%) of untreated levels (Figure 4b). In experiments where triplicate injections were administered, the level of secretory impairment increased with the frequency of nanoparticle administration (Figure 4b). Although we cannot rule out an inhibitory effect of the nanoparticles on secretion, a similar decrease in SMG secretion rates occurred following retroductal injection of saline alone (Figure 4a). This data is consistent with the report by Yoshida et al.19 describing general “sialographic damage” caused by retroductal injection.

Figure 4.

Saliva secretion rates decrease following retrograde injection of saline or siRNA–nanoparticle complexes. Secretagogue-stimulated saliva was collected from cannulated SMGs for a 20-minute period. The saliva output is expressed as a ratio of secretion volume per wet gland weight, and values are normalized to those from untreated control Nkcc1+/− littermates. (a) Retroductal injections of saline only were used to establish “background” reduction in saliva secretion presumably resulting from the reverse hydrodynamic pressure generated during retrograde injection. Saliva secretion was stimulated at time points indicated and collected. (b) Changes in saliva secretion rates were measured at the time points indicated after single (striped bars) or triplicate (hatched bars) siRNA–nanoparticle injections, and normalized to the secretion levels measured from non-injected animals (data were corrected for the nonspecific reduction of 15.95 ± 7.95% in saliva output occurring after saline retrograde injection). The secretion rate determined in SMG from Nkcc1−/− mice is shown for comparison (black bar). (Means ± SEM, n = 3–5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001). (scr siRNA, scrambled siRNA; 3× scr siRNA, triple injection of scrambled siRNA; Nkcc1 siRNA, single injection of Nkcc1 siRNA; 3× Nkcc1 siRNA, triple injection of Nkcc1 siRNA). siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of Nkcc1 decreases saliva secretion and phenocopies the systemic Nkcc1 knockout in vivo

Systemic knockout of the Nkcc1 gene decreases stimulated SMG saliva secretion by ~60% compared with wild-type controls.16 To test the functional consequence of siRNA-mediated Nkcc1 knockdown, we measured saliva output as compared with that of Nkcc1−/− mice. Results are summarized in Figure 4b. At 2 days post-injection, saliva output was reduced to 52 (± 17%), comparable with the secretion rate measured in the Nkcc1−/− mice, which is 47 (± 2%) of wild-type animals. At 1 week, stimulated secretion from Nkcc1 siRNA-treated mice remained significantly decreased to 70 (± 11%) of the untreated controls (Figure 4b). Triplicate retroductal injections of siRNA targeting Nkcc1 elicited a more pronounced drop in saliva output. By day 2, the secretion rate decreased to 39 (± 18%) of untreated controls, and at 1 week, remained at only 53 (± 12%) of uninjected controls. These salivary flow rates are in the same range as those recorded in Nkcc1−/− mice (P = 0.983 and P = 0.979, respectively). In other words, retroductal injection of siRNAs targeting Nkcc1 in the SMG can phenocopy the functional consequences of a systemic Nkcc1 gene knockout. Triplicate injections of Nkcc1 siRNA were able to sustain this inhibitory effect on saliva secretion for 2 weeks at 61 (± 17%) of untreated controls.

Administration of siRNA–nanoparticles does not induce off-target gene silencing or apoptosis

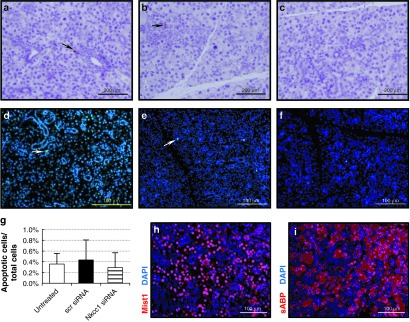

We next investigated whether the nanoparticle delivery of siRNAs caused unexpected off-target or deleterious side effects. Tissue response to the pH-responsive nanoparticle/siRNA complexes was analyzed using markers of apoptosis. Staining for caspase-3 (Figure 5a–c) and TUNEL assays (Figure 5d–f) at 1 week post-injection, demonstrated that apoptosis was not upregulated in comparison to untreated SMG. Evaluation at additional time points also did not reveal increased apoptosis (data not shown). These data were quantified by determining the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells to total DAPI-stained cells per microscopic field, which indicated no significant difference in the level of apoptosis between control and siRNA–nanoparticle-injected groups (Figure 5g).

Figure 5.

Analysis of mouse SMG for off-target effects following siRNA–nanoparticle retroductal injections. (a–c) Apoptosis was measured by staining for caspase-3–positive cells at 1 week post-injection. Sections were prepared from (a) SMG of untreated control, (b) SMG injected with scrambled (scr) siRNA–nanoparticle complexes, and (c) SMG injected with Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticle complexes. Fluorescent microscopic images of TUNEL apoptotic assay on (d) SMG of untreated control (green; arrow), (e) SMG injected with scrambled siRNA–nanoparticle complexes (green; arrow), and (f) SMG injected with Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticle complexes. (g) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells (green in d–f) counted from 10 random microscopic fields per gland. The percentage of apoptotic to total cells (labeled by DAPI; blue) is plotted (means ± SEM). (h) Immunohistochemistry with antibody to Mist1, an acinar cell-specific transcription factor (red), and (i) antibody to sABP, a cytoplasmic marker for acinar cells (red), demonstrates normal acinar cell gene expression in SMGs treated with Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticles at 1 week post-injection. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). For a–c, bar = 200 μm; for d–f,h,l, bar = 100 μm. (scr siRNA, scrambled siRNA). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

Additional histological analysis was performed to evaluate whether retroductal injection of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes triggers nonspecific effects on gene expression in SMG. Hematoxylin/eosin and periodic acid-Schiff staining of SMG sections from untreated controls and injected animals revealed no obvious histological changes (Supplementary Figure S3). Immunohistochemical staining for the secretory acinar cell markers, Mist1 (or Bhlha15; Figure 5h), or salivary androgen-binding protein α-subunit (sABP; Figure 5i) revealed no obvious change in their expression patterns following Nkcc1 siRNA injection, compared with the control sections (Supplementary Figure S4). Thus, we observed no potential off-target effects altering acinar cell-specific expression profiles in the secretory cells. Furthermore, the siRNA–nanoparticle injections did not affect the body weight of experimental animals (data not shown).

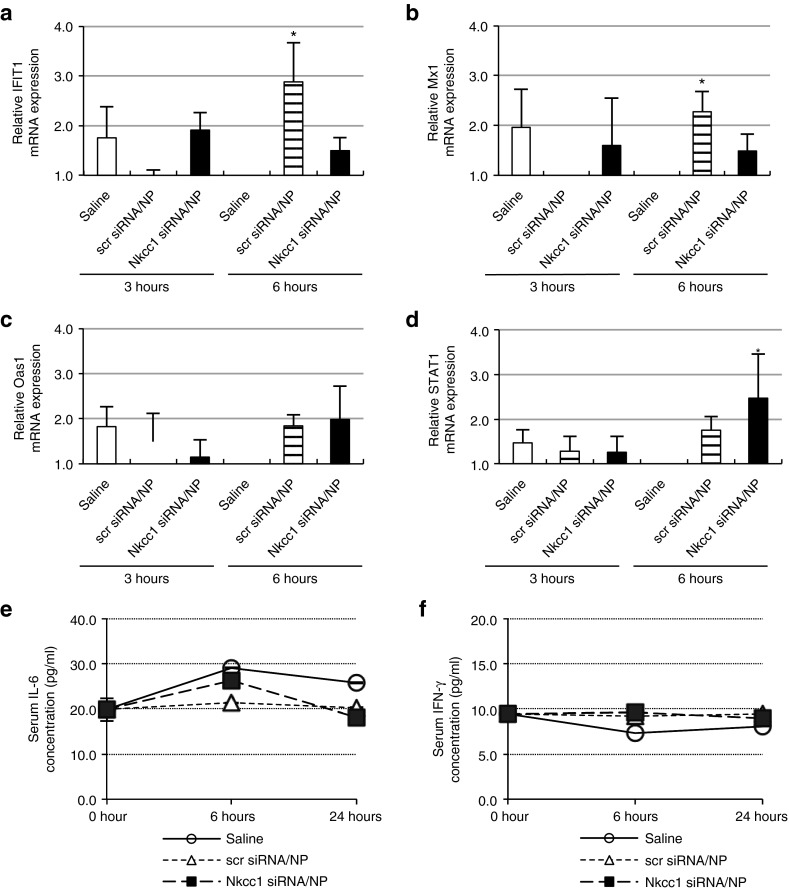

Injection of siRNA–nanoparticles elicits only limited local and systemic immune responses

In some cases, nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery has been linked to potent immune stimulation, in part due to nanoparticle vehicle-related toxicity.20 To establish whether the pH-responsive nanoparticles used in this study might elicit an immunologic response, we monitored the expression of several immune-responsive genes in the cytokine and interferon pathways. Baseline mRNA levels were established using untreated, healthy mice. mRNA expression levels of the Oas1, STAT1, Mx1, and IFIT1 genes21,22 were measured by quantitative PCR at 3 and 6 hours post-injection in SMGs isolated from saline-injected (vehicle only) controls, and from animals injected with siRNA–nanoparticles. An increase of greater than twofold was scored as induced gene expression. Injection of scrambled siRNA–nanoparticles increased expression of IFIT1 (Figure 6a) and Mx1 (Figure 6b) genes by 2.9- and 2.3-fold, respectively, within 6 hours, although these increases were not observed following injection of Nkcc1 siRNAs. Nkcc1 siRNA injection induced STAT1 (Figure 6d) overexpression by 2.5-fold at 6 hours after retrograde injection. No significant difference was recorded in the level of Oas1 expression in either the control or siRNA–nanoparticle-treated SMGs at either time point (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

siRNA–nanoparticle injection elicits only limited local and systemic immune responses. Expression of cytokine or interferon pathway immunoresponse genes, (a) IFIT1, (b) Mx1, (c) Oas1, and (d) STAT1 analyzed at 3 and 6 hours post-injection by quantitative RT-PCR of SMG tissue (Data pooled from three separate quantitative PCR experiments on all samples, and compared with untreated controls; means ± SEM, *P < 0.05). (e) Serum levels of IL-6 were measured using ELISA assay on serum collected at 6 and 24 hours after injection with saline, scrambled siRNA–nanoparticles, or Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticles. Initial measurements at “0” time point were obtained from serum collected before siRNA injection. (f) Serum levels of IFN-γ were measured using ELISA assay on serum collected at 6 and 24 hours after injection with saline, scrambled siRNA–nanoparticles, or Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticles. Initial measurements at “0” time point were obtained from serum collected before siRNA injection. (Means ± SEM; n = 3) (scr siRNA, scrambled siRNA; NP, nanoparticles). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

Systemic innate immune activation was assessed at 6 and 24 hours post-injection in serum using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays23 for interleukin-6 (Figure 6e) and interferon-γ (Figure 6f). We observed no significant increase in serum levels of either protein in mice treated with siRNA–nanoparticle complexes, as compared to those injected with saline alone.

Taken together, no other side effects beyond those expected based on the Nkcc1−/− phenotype were observed. These findings validate the siRNA–nanoparticle approach as a practical and specific method for gene therapy in the SG.

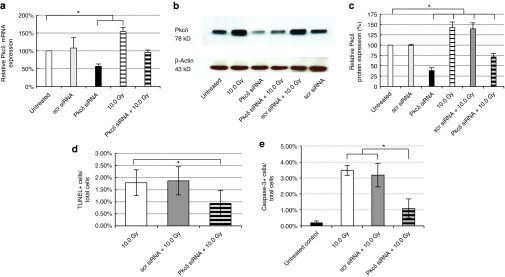

In vivo knockdown of the proapoptotic protein, Pkcδ, in the mouse SMG

The effective knockdown of Nkcc1 expression in the SMG established that siRNA–nanoparticle complexes are effective at targeting SG gene expression in vivo. We next targeted the proapoptotic gene Pkcδ to test whether in vivo knockdown can protect against radiation-induced SG damage. siRNAs targeting Pkcδ (SMARTpool of four functional siRNAs) were complexed with pH-responsive nanoparticles and retroductally injected into the SMG of wild-type BALB/c females. Analysis of the glands was performed to measure both Pkcδ mRNA and protein levels as described earlier for Nkcc1. Quantitative PCR analysis (Figure 7a, black bar) at day 2 post-injection showed that Pkcδ mRNA expression was decreased by 43%, compared with untreated controls, and by 51% compared with scrambled siRNA-injected controls.

Figure 7.

In vivo application of siRNA blocks radiation-induced increase of the proapoptotic protein Pkcδ. Pkcδ knockdown was achieved through a single retrograde injection of siRNAs targeting the Pkcδ gene. All siRNA injections were done in complex with nanoparticles. (a) RNA samples were prepared from five sample groups to compare Pkcδ gene expression changes between control SMG and SMGs receiving scrambled (scr) or Pkcδ siRNAs, with or without radiation exposure (10.0 Gy), as well as those receiving radiation alone. Results are based on quantitative RT-PCR, and the level of Pkcδ mRNA measured in untreated control samples was set at 100% (means ± SEM, n = 3–5, *P < 0.05). (b) Pkcδ protein expression levels in each sample were analyzed on western blots at 48 hours after treatment. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody as control. (c) Pkcδ protein expression was quantified based on protein band intensities measured on western blots (shown in b) using Image J. The level of Pkcδ protein measured in untreated control samples was set at 100% (means ± SEM, n = 3–5, *P < 0.05). (d) The number of apoptotic cells per total cells detected on sections (n = 10) of irradiated SMGs was established using the TUNEL assay, and compared with the numbers detected after pre-administration of scrambled (scr) or siRNAs targeting Pkcδ. (e) The ratio of apoptotic cells to total cells was also determined at 48 hours after irradiation by staining for active caspase-3 in nonirradiated SMG (untreated control), and in irradiated SMG, either non-injected (10.0 Gy), or pretreated with scrambled siRNA (scr) or Pkcδ siRNA (means ± SEM, *P < 0.05). RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

It is well established that radiation treatment induces an increase in Pkcδ gene expression.18 Our data indicates that a local exposure of 10 Gy (anterior neck region only) resulted in upregulation of Pkcδ mRNA by 54%, compared with untreated controls (Figure 7a). However, when siRNAs targeting Pkcδ were retrogradely injected into the SMG before radiation, this upregulation was not observed. The level of Pkcδ mRNA detected was preserved at the level of untreated animals, which demonstrates that siRNA treatment abrogates radiation-induced upregulation of the Pkcδ gene.

Pkcδ protein levels were analyzed at 2 days postirradiation on western blots (Figure 7b) and protein band intensities were quantified using Image J (National Institutes of Health). The protein level measured in untreated control SMGs was set at 100%. Results are summarized in Figure 7c. Injection of siRNA targeting Pkcδ reduced Pkcδ protein expression to 38 (± 7%) of the untreated controls at day 2 post-injection. Radiation treatment induced Pkcδ protein production to 142 (± 14%) compared with the untreated controls. Pre-injection of scrambled siRNA 2 days before radiation treatment had no significant effect on the upregulation of Pkcδ protein (139 ± 14% of untreated control). However, pre-treatment with siRNA targeting Pkcδ significantly blocked the increase in Pkcδ protein level by 71% (P = 0.002) of irradiated controls. This significant difference in Pkcδ protein levels relative to irradiated mice treated with scrambled siRNA (68% higher; P = 0.003) demonstrates that Pkcδ siRNA–nanoparticles can efficiently knockdown Pkcδ expression in vivo.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of Pkcδ in vivo confers radioprotection to mouse SMG

Knockout of the proapoptotic Pkcδ gene suppresses apoptosis in SG cells in response to irradiation.17 We have previously demonstrated that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Pkcδ in cultured SG cells also confers protection against radiation-induced apoptosis.12 To determine whether siRNA-mediated knockdown can protect animals against SMG damage induced by radiation treatment, we analyzed SMGs in which Pkcδ was targeted with Pkcδ siRNA–nanoparticle complexes before irradiation.

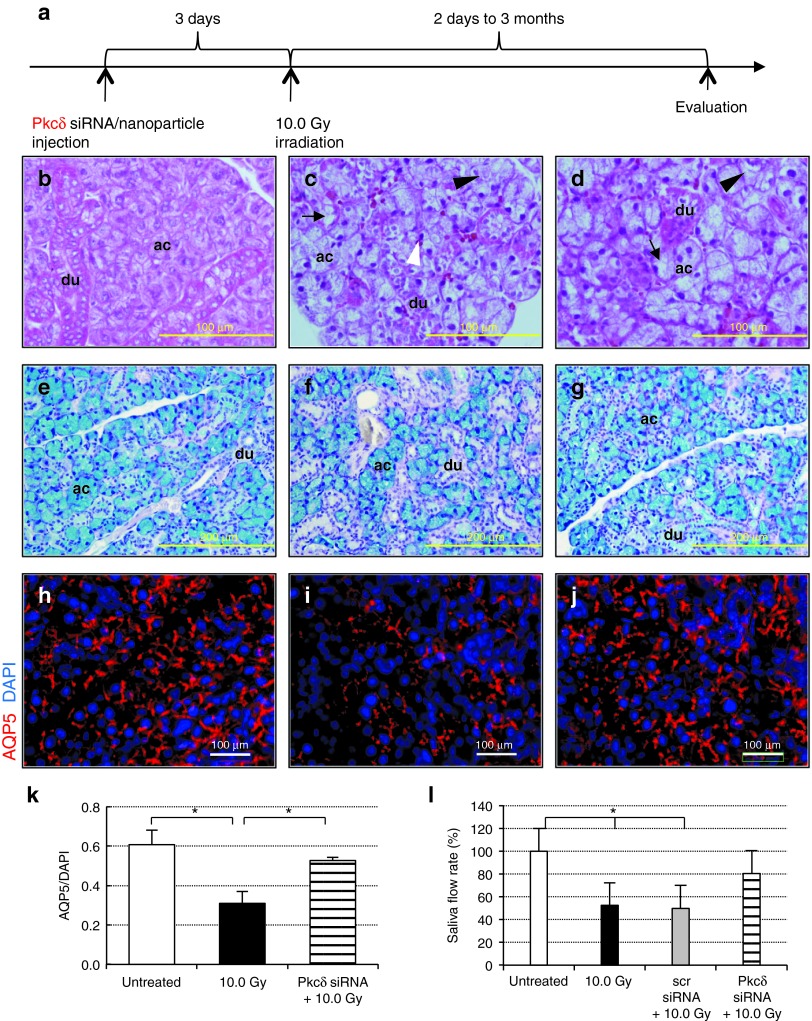

The experimental strategy is illustrated in Figure 8a. Based on the Nkcc1 knockdown efficiency of >45% measured at day 2 post-injection, radiation treatment of 10 Gy was administered on day 3, to ensure that radiation is performed within the effective knockdown window.

Figure 8.

Targeted in vivo delivery of Pkcδ siRNA confers radioprotection to the SMG. (a) Timeline of experimental procedure. Scrambled or Pkcδ siRNA–nanoparticle complexes were administered by retrograde injection into the SMG 3 days before irradiation (10.0 Gy). Phenotypic changes were assessed at various time points using morphological and immunohistochemical methods. H/E staining of (b) untreated, normal gland, (c) 10.0 Gy irradiated gland, and (d) Pkcδ siRNA-treated, irradiated gland at 3 months postirradiation (black arrow: cytoplasm vacuolization; black arrowhead: acinar cell lysis; white arrowhead: pycnotic nucleus). (e–g) Alcian-blue/PAS-stained sections at 3 months postirradiation (acinar cells (ac), blue; ducts (du), pink; nuclei, dark blue) from (e) untreated gland, (f) irradiated gland, and (g) Pkcδ siRNA-treated, irradiated SMG. (h–j) Immunohistochemical detection of AQP5 at 3 months postirradiation. AQP5 expression (red) in (h) untreated, (i) irradiated only, and (j) Pkcδ siRNA-treated, irradiated SMG at 3 months postirradiation. (k) Relative AQP5 protein expression at 3 months postirradiation was calculated by dividing AQP5-positive (red fluorescent) areas by total DAPI-positive (blue) areas in 10 randomly selected SMG regions from three animals per sample group. (l) Changes in the SMG saliva flow rate, 3 months after ionizing radiation. Pilocarpine-stimulated saliva was collected for 20 minutes and normalized to SMG weight (n = 3–5). (All error bars represent SEM; *P < 0.05; for a–c,h–j, bar = 100 μm; for e–g, bar = 200 μm; scr siRNA, single injection of scrambled siRNA–nanoparticles; Pkcδ siRNA, single injection of Pkcδ siRNA–nanoparticles; 10.0 Gy, ionizing radiation dose). AQP5, aquaporin 5; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; H/E, hematoxylin/eosin; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff staining; siRNA, small-interfering RNA; SMG, submandibular gland.

Radiation-induced damage in the mouse SMG remains apparent at 90 days following treatment.24 To confirm the radiation response, we performed histological evaluations comparing untreated, healthy glands (Figure 8b,e) with irradiated glands (Figure 8c,f) 3 months after radiation exposure. Compared with these images, a visible improvement in gland morphology was apparent in sections of SMG treated with Pkcδ siRNA before irradiation (Figure 8d,g). The siRNA-treated SMGs retained noticeably more acinar cells after irradiation than did the controls.

Acinar cell depletion is primarily due to apoptosis in the early phase of radiation damage.25 Medina et al.26 detected the most prominent apoptosis 3 days after irradiation in rat SMG. We therefore determined the level of apoptosis at that time point through detection of TUNEL-positive cells (Supplementary Figure S5a). The number of apoptotic cells (Figure 7d) was approximately fivefold higher in irradiated samples (1.7 ± 0.6%) compared with control samples (0.4 ± 0.2%, see control level in Figure 5g). However, the preventive knockdown of Pkcδ resulted in a statistically significant reduction in apoptotic cell frequency (0.9 ± 0.5%, P = 0.048) (Figure 7d). More robust changes in apoptosis were detected using an antibody to active caspase-3 at 48 hours after irradiation (Supplementary Figure S5b). Radiation treatment increased cellular apoptosis by >15-fold in irradiated or scrambled siRNA-treated and irradiated animals. However, pre-treatment with Pkcδ siRNA markedly reduced the number of caspase-3–positive cells by 70% (Figure 7e).

The expression of AQP5, an acinar cell-specific membrane channel, is significantly downregulated in irradiated rat SGs.27 We therefore examined the acinar cells for AQP5 expression at 3 months postirradiation. As expected, immunostaining of irradiated glands with an antibody to AQP5 demonstrated a significant decrease in AQP5 expression (49 ± 10%; Figure 8i,k) relative to untreated, control tissue (Figure 8h). In contrast, pre-treatment with siRNA targeting Pkcδ contributed to preservation of specific, luminal expression of AQP5 (Figure 8j). Quantification revealed that a single injection of Pkcδ siRNA–nanoparticle complexes attenuated the effect of radiation on AQP5 expression, which decreased by only 13% from untreated controls (Figure 8k). Likewise, immunostaining with antibodies to the acinar cell markers, Mist1 and sABP revealed conserved expression patterns of both proteins in the Pkcδ siRNA-pretreated SMGs compared with irradiated glands (Supplementary Figure S5a).

The most biologically relevant method for evaluating SG function is the measurement of saliva secretion.28 Stimulated saliva production rates were determined in control and experimental groups, at 90 days following radiation exposure. Saliva secretion was stimulated with pilocarpine, and saliva was collected by cannulating the SMG excretory ducts. The data are summarized in Figure 8l. Saliva secretion from irradiated SMGs is decreased to only 53 (± 17%) of untreated control animals. SMGs pretreated with scrambled siRNAs before irradiation were not protected and showed the same low level of secretion (P = 0.998). However, a markedly improved saliva secretion was measured in SMGs pretreated with siRNA targeting Pkcδ. The animals in this group demonstrated only a fractional drop in secretion to 80 (± 26%) of the level measured in untreated control glands. This is an increase in saliva secretion of over 50% above that produced by irradiated control glands. We conclude that pre-emptive knockdown of Pkcδ in the SMG can alleviate radiation-induced hyposalivation, and thereby confer functional radioprotection in vivo.

Discussion

We have demonstrated both the effectiveness and therapeutic potential of siRNA-mediated radioprotection in vivo, using nanoparticles as delivery carriers in the mouse SMG. The use of siRNAs to modulate gene expression in vivo must overcome several challenges, including stability, the ability to cross cell membranes, and the transient nature of gene knockdown.2 We previously validated efficient siRNA delivery in vitro,12 using a novel, pH-responsive nanoparticle formulation.29 In vitro, the nanoparticle carriers mediated intracellular uptake to >70% of cultured cells.12 Moreover, efficient release of functionally active siRNA was demonstrated through measurable knockdown of both mRNA and protein expression of the targeted genes.

In this study, we administered siRNA–nanoparticle complexes into the SMG by retroductal injection, a noninvasive and reproducible procedure, which allows single or repeated injections into the gland. Retroductal injection is a localized treatment without obvious systemic effects.5 Previous studies have suggested limited dissemination of viral vectors injected into the SMG or parotid glands to other tissues.30 We targeted the SMG, due to its size and accessibility, but similar experiments, using recently described techniques,30 should also be performed in the parotid gland, as it is the largest and most radiosensitive among the major SGs in humans.4

We observed no significant off-target effects or measurable systemic immunologic response following siRNA–nanoparticle injections. However, initial results indicated that retroductal injections did alter saliva secretion. Further investigation revealed that injection of saline alone into the SMG results in a nonspecific and transient decrease in saliva secretion. This finding corroborates an earlier study, which demonstrated that overall saliva secretion is reduced following isotonic saline injection into rat SMG.19 Although the mechanism is not yet clear, the rise of intraductal pressure may cause mechanical stress and disrupt intercellular tight junctions. However, this decrease has not been observed in humans following retroductal injection.31 We note that a temporary reduction in salivary secretion may result in longer gland retention of siRNAs after injection, enabling increased cellular uptake.

In vivo, siRNA–nanoparticle complexes were internalized into ~40% of the total SMG cell population. Thus, siRNA cellular uptake using nanoparticles is significantly more efficient than that achieved in SGs with other nonviral delivery methods such as electroporation or sonoporation.10,32 The simplicity of complexing siRNAs with nanoparticle carriers eliminates the need for such techniques, and reduces time and cost for potential clinical applications. Although only a fraction of SMG cells internalized siRNA–nanocomplexes, whole SMG analysis showed significant knockdown at both mRNA and protein levels. Thus, the functional effects of knockdown, as evidenced by saliva secretion, are probably underestimated. Nevertheless, it will be critical to increase the efficiency of cellular uptake to optimize functional outcomes. A recent report demonstrated that β-adrenergic stimulation increased the endocytic uptake of plasmid DNA into acinar cells.33 As the siRNA–nanoparticle complexes are internalized by endocytosis, this may suggest a means of increasing siRNA uptake as well.

Therapeutic applications of RNA interference are limited by the transient nature of the gene knockdown. However, the short half-life of siRNAs can be used to an advantage in devising radioprotective strategies. In general, proapoptotic genes are essential for maintaining normal cell homeostasis. Long-term silencing of these endogenous regulators of proliferation and cell cycle progression is undesirable and may be detrimental. In our approach, the transient siRNA-mediated knockdown ensures that gene expression is downregulated only within a defined window of time. We hypothesize that the transient suppression of apoptosis may allow the DNA repair machinery a chance to fix chromosomal lesions, and could function to reduce the loss of acinar cells. Furthermore, the combination of transient knockdown and repetitive injections can be readily adapted to fractionated radiation treatments administered to human patients.

Pkcδ functions as a proapoptotic mediator downstream of p53 in the SGs.18,34 The activation of Pkcδ by caspase cleavage is an irreversible event that acts to amplify the proapoptotic signal.35 In contrast, knockout of Pkcδ protects the SMG and parotid glands from radiation-induced apoptosis.17 We tested whether targeting the Pkcδ gene by siRNA-mediated knockdown can mitigate radiation-induced damage in the SG. Indeed, blocking the endogenous increase in Pkcδ expression that occurs within 48 hours after radiation exposure results in reduced apoptosis in the SMG and preserved secretory function.

Radiation-induced apoptosis in the SGs occurs predominantly in the secretory acinar cells.17 It will be important to identify whether cells protected by knockdown of Pkcδ include any of the potential progenitor populations known to be involved in SG repair and maintenance. It is also essential to determine the fate of those cells that would otherwise have undergone apoptosis, as it is well established that the inhibition of apoptosis is a hallmark of oncogenesis.36,37 However, like Pkcδ knockouts, mice homozygous for knockout of the Puma gene are also resistant to radiation-induced apoptosis, and no increase in malignancies have been observed in this transgenic line.38 The radioprotective effects associated with the Puma knockout were attributed to better maintenance of cell quiescence and to more efficient DNA repair in protected cells. Recent evidence demonstrating that bulge cells of the hair follicle respond to proapoptotic signals by rapidly clearing p53 and attenuating cell loss39 suggests that apoptosis may not be an obligatory cellular response to irradiation.

There are alternative targets that may warrant investigation for optimization of the radioprotective effect. Several other genes are known to be critical for the apoptotic response in SGs, including the p53 transcriptional targets Puma, Noxa, and Bax.40,41 Another potential candidate is GSK3.42 In addition, the identification of siRNA targets that specifically confer protection to microvessels,7 neural cells,43 or stem/progenitor cells44 may prove effective in radioprotection of SGs. The administration of several siRNAs targeting multiple genes could also be a viable approach. For example, a recent study demonstrated that siRNA-mediated knockdown of tumor necrosis factor-α prevents radiation-induced fibrosis,45 and could suggest a means of reducing the acute inflammatory response associated with radiation treatment. The in vivo application of siRNA could also be applied to the development of strategies to treat oral infections, or other oral health conditions.

In summary, this study has achieved two goals. First, we have demonstrated that retroductal injection of siRNA, using nanoparticles for delivery, achieved measurable in vivo knockdown of two independent genes in the SMG. Second, we have established that targeting of the proapoptotic mediator, Pkcδ, before radiation treatment protected the glands from radiation-induced damage and the resultant hyposalivation. Our approach has significant advantages over alternative methods, as it is non-systemic, nonviral, and induces only a transient effect on endogenous gene expression. Our results suggest that optimization of in vivo siRNA-mediated silencing for clinical application could be an effective means of protecting SG in the radiation treatment of head and neck cancers.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Adult female BALB/c/cByJ mice 8–10 weeks of age were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used for all siRNA knockdown experiments. The generation of the Nkcc1 knockout (−/−) strain was previously reported.46 Nkcc1−/− and Nkcc1+/− littermates were used as positive and negative controls in the Nkcc1 knockdown experiments. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All procedures and protocols were approved and conducted in compliance with the University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY.

Synthetic siRNAs. ON-TARGET plus siRNA reagents used in this study were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO). The duplexes are modified on both strands for in vivo use and SMART pooled against the murine Nkcc1 target gene (Slc12a2; #L-044448-01, gene ID: 20496) or the murine Pkcδ gene (#L-040147-00, gene ID: 18753). Pre-designed non-targeting control siRNA (#D-001810-01) was injected as negative control. For initial injection experiments, siGLO Cy3-labeled fluorescent siRNAs (#D-001620-03 and #D-001630-02) were injected as transfection indicators for tracking siRNA uptake.

Preparation of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes. The synthesis and characterization of pH-responsive diblock copolymers and resulting nanoparticles has been previously reported.14 Briefly, reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer polymerization was utilized to polymerize dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) blocks. The polymerization was conducted in a nitrogen atmosphere in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at 30 °C for 12 hours. To add the second block of the diblock copolymer, pDMAEMA macroCTA was isolated and added to DMAEMA, propyl acrylic acid, and butyl methacrylate in DMF at 1:1:2 molar ratios. The final molecular weight of the diblock was 28,500 g/mol with a polydispersity index of 1.3. Diblock copolymers were solubilized in highly concentrated stock solutions (~1 g/ml) in ethanol and diluted to 2 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This solution was then utilized to form complexes with siRNA and injected into animals. Charge ratio, which represents the ratio between the protonated DMAEMA residues of the pDMAEMA block (where 50% of the residues are protonated at physiological pH) and the negatively charged siRNA, was kept constant at 4:1. The size of complexes (or polymer alone) was 50–60 nm. In addition, zeta potential was similar across all conditions with values of ~10 mV.

In vivo siRNA delivery into SMGs. Retroductal injections into the main excretory duct of SMG were administered intraorally according to the experimental procedures elaborated by Zheng et al.47 Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg; Bioniche Pharma, Lake Forest, IL) and xylazine (10 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA) injected intraperitoneally. Heating pads were used to control the body temperature of animals during the procedure. A mouse intracranial catheter (#CS-32; Braintree scientific, Braintree, MA) was inserted into the sublingual orifice of the Wharton duct under microscopic visualization to allow retroductal injections into the left SMG. To prevent saliva backflow, intramuscular atropine (0.5 μg/g body weight, A0257; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was administered (injection pressure was maintained for 3 minutes). siRNA–nanoparticle conjugations were formulated 20 minutes before the injections and the dosing volume was adjusted with sterile, RNase-free PBS, pH 7.4 (Ambion, Grand Island, NY). The animals were randomly divided into three groups, which received saline, scrambled (nonspecific) siRNA–nanoparticles, or target gene siRNA–nanoparticles. Nanoparticle/siRNA formulations were freshly prepared before the injections by mixing the nanoparticles (1 μg/ml) with siRNA. Mice were given retrograde injections of 4 μg siRNA/gland (15–20 μl) in a single injection or in triplicates on three consecutive days using a 27-gauge Hamilton Microliter syringe (#7637-01; Hamilton Company, Reno, NV). The animals were kept immobilized for 15 minutes after which the catheter was carefully removed.

Real-time quantitative PCR. SMG were harvested at different time points after retrograde injections. Total RNA was purified from homogenized tissues using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genomic contamination was avoided using on-column DNase 1 (#79254; Qiagen) digestion. RNA concentration was calculated from the OD260/OD280 absorption ratio using a SmartSpec Plus spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis was completed in two steps. Reverse transcription was performed with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was then amplified in quantitative PCR reactions set up in 25 μl total volume containing 10 μl of 2x IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 2.0 μl of template (0.5 μg) and 0.75 μl of forward and reverse target-specific primers (10 pmol/μl), respectively. The primer sequences were determined from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank) and are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Samples were analyzed using the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the following cycling parameters: pre-incubation (95 °C for 10 minutes), 45 cycles of amplification (denaturing at 95 °C for 15 seconds, annealing at 62 °C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72 °C for 30 seconds), and melting curve analysis (from 65 to 95 °C, 0.5 °C temperature increments) with continuous fluorescent measurement. Standard curves from control dilution series were created for each target and reference gene, and target gene expression levels were normalized to three reference genes (UBC, ubiquitin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; S18, ribosomal protein).48 Quantification cycle (Cq) values were imported to Biogazelle qbasePLUS software (Biogazelle NV, Zwijnaarde, Belgium) and normalized expression levels relative to control (untreated) samples were computed from triplicate experiments for each sample.

Western blot. SMGs from control and siRNA-injected animals were harvested and homogenized in 1 ml ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (G-Biosciences, Maryland Heights, MO) containing 1x complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini tablets; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Samples then were incubated at 95 °C for 5 minutes in 4x-Laemmli's buffer (200 mmol/l Tris-HCl, 400 mmol/l β-mercaptoethanol, 8% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 40% glycerol; analytical grade reagents from Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentration was calculated using the bicinchoninic acid assay method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins (10 μg) were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 4–15% (wt/vol) acrylamide gels (RGEL; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilion-P; Millipore, Billerica, MA). After rinsing and blocking (5% dried skim milk in Tris-buffered saline), the blots were probed with primary antibody. Antibodies used included: rabbit polyclonal antibody against Pkcδ (1:500, cs-213; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit polyclonal antibody against Nkcc1 (1:3,000, ab59791; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (1:1,000, sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies used were goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (cs-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (cs-200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. α-Image scanning of the blots was performed to measure the difference in band intensity between samples and for normalization with controls.

Immunohistochemical analysis. SMGs from injected animals were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C (except siGLO siRNA-injected glands, which were fixed for only 2 hours at 4 °C). Tissues were either paraffin embedded or frozen in OCT compound (fluorescently labeled siRNA samples) and then cut into 5 μm sections. For antigen retrieval, the slides were treated with HIER buffer (Tris-EDTA, pH 8.0) in a pressure cooker for 8 minutes and then blocked in 10% donkey serum in PBS. Permeabilization for frozen sections was performed with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes. Immunostaining was performed overnight (at 4 °C) with primary antibodies, which included goat polyclonal Nkcc1 (1:200, sc-21545; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal Mist1 (1:500, gift from Dr Stephen Konieczny, Purdue University), rabbit polyclonal sABP α-subunit (1:100, gift from Dr Art Hand, University of Connecticut), goat polyclonal AQP5 (1:300, sc-9890; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit polyclonal early endosomal marker (EEA1, 1:100, ab-2900; Abcam). FITC- or Cy3-conjugated donkey IgG was diluted 1:500 (Jackson ImmunoRes Lab, West Grove, PA) as secondary antibody and applied on sections for 1 hour at room temperature. Following a PBS rinse, 10 μg/ml DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PBS was applied to sections for 5 minutes. The sections were washed two times in PBS for 5 minutes and the slides were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Microscopic images were acquired with an inverted fluorescent microscope (IX81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital CCD camera (C8484-03G01; Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Japan). For quantification of Nkcc1 or AQP5 protein expression, representative photomicrographs/sections were taken (n = 5) at ×400 magnification and evaluated using the Image J (National Institutes of Health) analysis software.

Saliva collection. Saliva was collected from saline-treated, control siRNA-treated, or Nkcc1 siRNA-treated animals on days 2, 7, 14, and 28 after retroductal injection. Saliva collection from Pkcδ siRNA-treated mice was performed 3 months following the irradiation. The surgical procedure has been developed as a non-recovery surgery before killing the animals. Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine cocktail, and 32-gauge tubing was inserted into the orifice of the main excretory duct of the SMG. After tracheotomy, saliva secretion was stimulated with an intraperitoneal injection of the muscarinic receptor antagonist pilocarpine (5 mg/kg, P6503; Sigma-Aldrich) and saliva from the cannulated SMG was collected into preweighted glass capillary tubes (TW150F-4; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) for 20 minutes. At the end of the procedure, the animals were killed and the SMGs were dissected. Salivary flow rate measurements were based on calculation of the saliva volume (density is assumed to be 1.0 mg/ml by Epperly et al.)49 divided by the SMG weight.

Apoptosis assays. Detection of apoptotic cells in samples following siRNA–nanoparticle injections was achieved using the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, the samples were fixed in 4% methanol-free formaldehyde, paraffin embedded and cut into 5 μm sections. The slides were treated with Proteinase K, then covered with equilibration buffer containing FITC-conjugated UTP, and incubated in the dark for 1 hour at 37 °C. Cells with the fragmented DNA were labeled with fluorescein-12-dUTP and the apoptotic cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The ratio of TUNEL-positive cells to total DAPI-stained nuclei was recorded from five random fields of each sample at ×400 magnification. Endogenous caspase-3 activation was examined following Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticle injections using the SignalStain Cleaved Caspase-3 detection kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) on paraffin-embedded tissue sections. For detection of the active form of caspase-3 in cells undergoing apoptosis following irradiation, a rabbit Caspase-3 antibody (ab2302; Abcam) was used. After deparaffinization and heat-induced antigen retrieval steps, the slides were immersed in 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase, and treated with the Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (SP-2001; Vector Laboratories). The Vectastain Elite ABC kit (PK-6101; Vector Laboratories) and DAB substrate kit (SK-4100; Vector Laboratories) were used for detection, following the manufacturer's protocols.

Flow cytometry. Twenty-four hours after injection with Cy3-tagged siRNA–nanoparticle complexes, SMGs were excised and enzymatically digested as described.50 Single cells were resuspended in PBS (with 2% fetal bovine serum and 0.01% trypan blue). A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed per sample on a BD LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Gating was determined using untreated control samples.

Immune response analysis. For serum cytokine arrays, whole blood samples were collected from untreated controls and from mice treated with saline, scrambled control siRNA–nanoparticle complexes, or Nkcc1 siRNA–nanoparticle complexes, at 6 or 24 hours following retrograde injection. After 1 hour clotting at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged (3,000 rpm) for 15 minutes at 4 °C and the serum was separated and transferred to −80 °C until cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were performed. The serum levels of interferon-γ and interleukin-6 were measured using the mouse ELISA kits (KMC4021 and KMC 0061; Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) according to the manufacturers' protocol. Data were obtained from three animals for each sample type and time point.

In vivo irradiation. Radiation experiments were used to induce xerostomia and acinar depletion in mouse SMG.

Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail administered intraperitoneally and the head-and-neck region was positioned over the slit of a custom-built collimator, which allowed shielding of the whole body. SMGs were exposed to a single dose of 10.0 Gy radiation delivered from a Cs137 radiation source. Animals were allowed to recover for 3 days to 3 months. At the end of the recovery period, saliva flow rates were determined and the SMGs were harvested. The tissue was fixed, sectioned, and subjected to morphological and histomorphometric analysis, as well as to immunohistochemical and immunoblot analyses.

Statistical analysis. Experimental data were analyzed using the analysis of variance method followed by the Newman–Keuls post hoc test. All values represent means ± SEM. P values <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant results. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS (IBM Statistics 20; IBM, Armonk, NY) software for Windows.

Supplementary Material Figure S1. Retroductal injection into mouse SMG. Figure S2. Cellular uptake of siRNA–nanoparticle complexes is confirmed by FACS analysis. Figure S3. Histology of SMG is not altered following siRNA–nanoparticle injections. Figure S4. Immunohistochemistry to detect expression of acinar cell-specific markers in SMGs. Figure S5. Radiation-induced apoptosis and secretory cell impairment is attenuated after Pkcδ knockdown in irradiated SMG compared with irradiated controls. Table S1. Quantitative PCR primer sequences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Rogers and Marilyn Elliott for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Dirk Bohmann (University of Rochester) for insightful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. In addition, the kind gifts of antibodies from Stephen Konieczny (Purdue University), and Art Hand (University of Connecticut Health Center) are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants R21 DE19302 (S.D. and C.E.O.), and R01 DE08921 (C.E.O.). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Jensen SB, Pedersen AM, Vissink A, Andersen E, Brown CG, Davies AN, Salivary Gland Hypofunction/Xerostomia Section; Oral Care Study Group; Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO) et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: management strategies and economic impact. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1061–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interference-based therapeutics. Nature. 2009;457:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Samul R, Silva RL, Akiyama H, Liu H, Saishin Y, et al. Suppression of ocular neovascularization with siRNA targeting VEGF receptor 1. Gene Ther. 2006;13:225–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BJ, Wellner RB, Zheng C. Gene transfer to salivary glands. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;213:93–146. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)13013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BJ, Voutetakis A, Wang J. Salivary glands: novel target sites for gene therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuni Y, Baum BJ. Gene delivery in salivary glands: from the bench to the clinic. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1515–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrim AP, Sowers A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Prevention of irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction by microvessel protection in mouse salivary glands. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2101–2106. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MR, Yamano S, Lodde BM, Wang J, Couwenhoven RI, Yakar S, et al. Local adeno-associated virus-mediated interleukin 10 gene transfer has disease-modifying effects in a murine model of Sjögren's syndrome. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1605–1618. doi: 10.1089/104303403322542257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauley KM, Gauna AE, Grichtchenko II, Chan EK, Cha S. A secretagogue-small interfering RNA conjugate confers resistance to cytotoxicity in a cell model of Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3116–3125. doi: 10.1002/art.30450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Kawaguchi M, Kosuge Y. siRNA-mediated gene silencing in the salivary gland using in vivo microbubble-enhanced sonoporation. Oral Dis. 2009;15:505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig GR, Behlke MA. Progress toward in vivo use of siRNAs-II. Mol Ther. 2012;20:483–512. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany S, Xu Q, Hernady E, Benoit DS, Dewhurst S, Ovitt CE. Pro-apoptotic gene knockdown mediated by nanocomplexed siRNA reduces radiation damage in primary salivary gland cultures. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1955–1965. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit DS, Henry SM, Shubin AD, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. pH-responsive polymeric sirna carriers sensitize multidrug resistant ovarian cancer cells to doxorubicin via knockdown of polo-like kinase 1. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:442–455. doi: 10.1021/mp9002255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertine AJ, Benoit DS, Duvall CL, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Development of a novel endosomolytic diblock copolymer for siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2009;133:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusonwiriyawong C, van de Wetering P, Hubbell JA, Merkle HP, Walter E. Evaluation of pH-dependent membrane-disruptive properties of poly(acrylic acid) derived polymers. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2003;56:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(03)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RL, Park K, Turner RJ, Watson GE, Nguyen HV, Dennett MR, et al. Severe impairment of salivation in Na+/K+/2Cl- cotransporter (NKCC1)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26720–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MJ, Limesand KH, Schneider JC, Nakayama KI, Anderson SM, Reyland ME. Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase Cdelta null mouse in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9728–9737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland ME, Anderson SM, Matassa AA, Barzen KA, Quissell DO. Protein kinase C delta is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19115–19123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Takai N, Uchihashi K, Kakudo Y. Sialographic damage in rat submandibular gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:426–430. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim MS, Kwon YJ. Efficient and targeted delivery of siRNA in vivo. FEBS J. 2010;277:4814–4827. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedmi R, Ben-Arie N, Peer D. The systemic toxicity of positively charged lipid nanoparticles and the role of Toll-like receptor 4 in immune activation. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6867–6875. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, McClintock K, MacLachlan I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urek MM, Bralic M, Tomac J, Borcic J, Uhac I, Glazar I, et al. Early and late effects of X-irradiation on submandibular gland: a morphological study in mice. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell AC, Redman RS, Evans RL, Ambudkar IS. Radiation-induced progressive decrease in fluid secretion in rat submandibular glands is related to decreased acinar volume and not impaired calcium signaling. Radiat Res. 1999;151:150–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina VA, Prestifilippo JP, Croci M, Carabajal E, Bergoc RM, Elverdin JC, et al. Histamine prevents functional and morphological alterations of submandibular glands induced by ionising radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2011;87:284–292. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2010.533247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhao D, Gong B, Xu Y, Sun H, Yang B, et al. Decreased saliva secretion and down-regulation of AQP5 in submandibular gland in irradiated rats. Radiat Res. 2006;165:678–687. doi: 10.1667/RR3569.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirix P, Nuyts S, Van den Bogaert W. Radiation-induced xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer: a literature review. Cancer. 2006;107:2525–2534. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertine AJ, Diab C, Prieve M, Paschal A, Hoffman AS, Johnson PH, et al. pH-responsive polymeric micelle carriers for siRNA drugs. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:2904–2911. doi: 10.1021/bm100652w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Shinomiya T, Goldsmith CM, Di Pasquale G, Baum BJ. Convenient and reproducible in vivo gene transfer to mouse parotid glands. Oral Dis. 2011;17:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes C, Cross HG, Baker CG, Chebib FS. The influence of gland size on the flow rate and composition of human parotid saliva. Dent J. 1978;44:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi T, Yoshizato K, Yamashiro S, Takeshima H, Sato K, Hamada K, et al. High-efficiency in vivo gene transfer using intraarterial plasmid DNA injection following in vivo electroporation. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1050–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sramkova M, Masedunskas A, Parente L, Molinolo A, Weigert R. Expression of plasmid DNA in the salivary gland epithelium: novel approaches to study dynamic cellular processes in live animals. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1347–C1357. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00262.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matassa AA, Carpenter L, Biden TJ, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. PKCdelta is required for mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29719–29728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Xia L, Chen GQ. Protein kinase cd in apoptosis: a brief overview. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2012;60:361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan GI, Vousden KH. Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer. Nature. 2001;411:342–348. doi: 10.1038/35077213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:485–495. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Shen H, Yuan Y, XuFeng R, Hu X, Garrison SP, et al. Deletion of Puma protects hematopoietic stem cells and confers long-term survival in response to high-dose gamma-irradiation. Blood. 2010;115:3472–3480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulou PA, Candi A, Mascré G, De Clercq S, Youssef KK, Lapouge G, et al. Bcl-2 and accelerated DNA repair mediates resistance of hair follicle bulge stem cells to DNA-damage-induced cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:572–582. doi: 10.1038/ncb2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila JL, Grundmann O, Burd R, Limesand KH. Radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction results from p53-dependent apoptosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Carson-Walter EB, Liu H, Epperly M, Greenberger JS, Zambetti GP, et al. PUMA regulates intestinal progenitor cell radiosensitivity and gastrointestinal syndrome. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thotala DK, Geng L, Dickey AK, Hallahan DE, Yazlovitskaya EM. A new class of molecular targeted radioprotectors: GSK-3beta inhibitors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Reed X, Vitale-Cross L, Gutkind JS, Hoffman MP. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1645–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1192046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima K, Inoue H, Nishiyama T, Mabuchi Y, Amano Y, Ide F, et al. Transplantation of side population cells restores the function of damaged exocrine glands through clusterin. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1925–1937. doi: 10.1002/stem.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawroth I, Alsner J, Behlke MA, Besenbacher F, Overgaard J, Howard KA, et al. Intraperitoneal administration of chitosan/DsiRNA nanoparticles targeting TNFa prevents radiation-induced fibrosis. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagella M, Clarke LL, Miller ML, Erway LC, Giannella RA, Andringa A, et al. Mice lacking the basolateral Na-K-2Cl cotransporter have impaired epithelial chloride secretion and are profoundly deaf. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26946–26955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Voutetakis A, Kok MR, Goldsmith CM, Smith GB, Elmore S, et al. Toxicity and biodistribution of a first-generation recombinant adenoviral vector, in the presence of hydroxychloroquine, following retroductal delivery to a single rat submandibular gland. Oral Dis. 2006;12:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver N, Cotroneo E, Proctor G, Osailan S, Paterson KL, Carpenter GH. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in the adult rat submandibular gland under normal, inflamed, atrophic and regenerative states. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperly MW, Carpenter M, Agarwal A, Mitra P, Nie S, Greenberger JS. Intraoral manganese superoxide dismutase-plasmid/liposome (MnSOD-PL) radioprotective gene therapy decreases ionizing irradiation-induced murine mucosal cell cycling and apoptosis. In Vivo. 2004;18:401–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisatomi Y, Okumura K, Nakamura K, Matsumoto S, Satoh A, Nagano K, et al. Flow cytometric isolation of endodermal progenitors from mouse salivary gland differentiate into hepatic and pancreatic lineages. Hepatology. 2004;39:667–675. doi: 10.1002/hep.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.