Abstract

Oral leukoplakia (OL) is the most common premalignancy in the oral cavity. A small proportion of OLs progresses to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). To assess OSCC risk of OLs, we investigated the role of the transcriptional repressor, Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2), in oral tumorigenesis and its clinical implication as an OSCC risk predictor. Immunohistochemistry was used to measure EZH2 expression in OLs from 76 patients including 37 who later developed OSCC and 39 who did not. EZH2 expression was associated with clinicopathologic parameters and clinical outcomes. To determine the biological role of EZH2 in OL, EZH2 level was reduced using EZH2-siRNAs in Leuk-1 cells, its impact on cell cycle, anchorage dependent/independent growth, and invasion was assessed. We observed strong EZH2 expression in 34 (45%), moderate expression in 26 (34%), and weak/no expression in 16 (21%) of the OLs. The higher EZH2 levels were strongly associated with dysplasia (P<0.001) and OSCC development (P<0.0001). Multivariate analysis indicated that EZH2 expression was the only independent factor for OSCC development (P<.0001). At 5 years after diagnosis, 80% of patients whose OLs expressed strong EZH2 developed OSCC whereas only 24% patients with moderate and none with weak/no EZH2 expression did so (P<0.0001). In Leuk-1 cells, EZH2 down-regulation resulted in G1 arrest; decreased invasion capability, decreased anchorage independent growth; down-regulation of cyclin D1 and up-regulation of p15INK4B. Our data suggest that EZH2 plays an important role in OL malignant transformation and may be a biomarker in predicting OSCC development in patients with OLs.

INTRODUCTION

Oral Leukoplakia (OL) represents the most common oral precancerous condition (1). It is a clinical term to describe lesions that present as a white patch and cannot be characterized clinically or histologically as any other disease. Histologically, OL has a wide spectrum, ranges from simple hyperkeratosis to severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ. Each clinical appearance or phase of OL has different transformation potential ranging from 1% to 47% in different studies (2). Malignant transformation often occurs several years after the onset of the white plaques but it can also occur within just few months or in decades (3, 4).

The prediction of OL’s malignant potential is unreliable in current clinical practice. The histopathological grading of dysplasia is still the most contemporary method to assess the malignant potential in patients with OL, yet this method is subjective and the clinical decisions based on the method are not satisfactory (5, 6). Considering the high morbidity and mortality associated with OSCC, the major challenges are to identify OLs with higher risk for OSCC development independent of dysplastic changes and to reveal molecular targets which may be regulated to prevent OSCC development (7, 9).

Development of OSCC is evolutionary and characterized by multistep carcinogenic processes, in which activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes are the key features leading to clonal expansion and malignant transformation of normal oral epithelial cells (9–11). Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) is the catalytic subunit of Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), a highly conserved histone methyltransferase that methylates lysine-27 of histone H3 (H3-K27) (12). H3-K27 methylation is commonly associated with DNA methylation and silencing of genes responsible for differentiation in organisms ranging from plants to mammals including humans (12, 13). It has been shown that EZH2 is involved in methylation and silencing of a subset of genes implicated in cell differentiation, suggesting that it may play a key role in cell differentiation and maintenance of adult stem cell populations (14,15). Furthermore, overexpression of EZH2 has been observed in several human cancer types including oral cancers, suggesting that EZH2 is an oncogene and plays a role in oral tumorigenesis (16–18).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that EZH2 activation is critical in malignant transformation of oral epithelial cells, and therefore may serve as an indicator to predict OSCC risk in patients with OLs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Specimens

Patients were selected from an archival database based on clinical diagnosis of OL from the period of 1993 through 2006 with follow-up information and available surgical biopsy samples at the time of diagnosis in the Department of Pathology and the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. The study was reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Thirty-seven OL patients who later developed OSCC were identified. Additional 39 OL patients who did not develop OSCC during the follow-up were selected from a larger pool of patients in the database. Paraffin tissue blocks were retrieved and sections were made for the proposed study. One of the tissue sections from each patient was stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and examined to verify histopathology diagnosis before further analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue, were cut into 4 μm tissue sections. The avidin-biotin complex (ABC) technique was done following Vectastatin elite ABC kit (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanol, treated with Tris-EDTA buffer for antigen retrieval, and quenched in hydrogen peroxide. Tissue sections were blocked with 2.5% normal serum, incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-EZH2 antibody (1:200), (clone 11, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA) followed by biotinylated secondary antibody then ABC reagent. Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen, and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich corp. St Louis, Mo). The EZH2 labeling index (LI) was defined semi-quantitatively as the intensity of staining (0, 1, 2, 3), multiplied by the percentage of positive epithelial thickness (25%, 50%, 75%) and given the scores: weak, moderate and strong, for the quartiles of the EZH2 LI: ≤75, 100 and ≥150 - ≤ 225, respectively, as the weighted mean of cells displaying nuclear immunoreactivity.19 For comparison, the samples were also analyzed using the Aperio ScanScope and Image Scope software, Nuclear v9 algorithm, with quartiles ≤75, >75 - <150, and ≥150, as weak, moderate and strong, respectively.

Cell culture

OL cell line (Leuk-1) (20) was cultured in keratinocyte serum-free (KSF) medium with 25μg/mL bovine pituitary extract (BPE) and 0.2 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Invitrogen).

SiRNA knockdown

Two anti-EZH2 siRNA, each targets the two splice variants of EZH2, and FAM labeled negative control siRNA, were purchased from (Ambion Inc). The anti-EZH2 siRNA sequences were 5′-GCUGACCAUUGGGACAGUATT-3′ for (siRNA-4916) and 5′-GUGUAUGAGUUUAGAGUCATT-3′ for (siRNA-4917). In vitro transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot

Cells were harvested in RIPA buffer (Sigma Aldrich). Whole cell lysate was separated in SDS-PAGE. Primary antibodies against EZH2 (clone 11, BD Transduction Laboratories), cyclin D1, cyclin D3, p16INK4A, p15INK4B, p27Kip1, CDK4, CDK6 (Cell Signaling Biotechnology) were used. Bands Quantification was done using the Image J processing and analysis software. GAPDH antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) was used to normalize protein loading.

Cell cycle analysis

Leuk-1 cells were harvested, fixed in 70% ethanol, suspended in PI/RNase staining Buffer (BD Pharmingen™) containing 0.1% Sodium Citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Cell proliferation assay

Viability of Leuk-1 cells transfected with EZH2 siRNA was measured every 24 h for 6 days using the Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (Roche Diagnostics Corporation). The experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

Anchorage-independent growth assay

24 h after EZH2 siRNA transfection, cells in 0.35% agarose with KSF, EGF and BPE medium were plated on top of solidified 0.5% agarose in 6-well plate in triplicates. The gels were covered with 1 ml medium and and incubated for 3 weeks with medium change every 3~4 days. Colonies >0.1 mm in diameter were counted under a microscopic field at 40x magnification. Means of colonies were calculated based on numbers from triplicate wells for each treatment condition.

In vitro cell invasion assay

BD BioCoat Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences) were used. EZH2 siRNA transfected leuk-1 cells were seeded in the upper chamber in KSF media without rEGF and BPE, while KSF media with rEGF and BPE was placed in the lower chamber. After 20 hours incubation, cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Cells in at least 6 random microscopic fields 100x were counted. The experiment was performed in duplicates and repeated 3 times.

Statistical analysis

Event free survival (EFS) or “OSCC free survival” was the outcome variable. The independent variable EZH2 expression status and its interaction with histology were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used for univariate associations between EZH2 expression status and EFS, and individual patient characteristics and EFS. The EFS rates at years 3 and 5 with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. The associations between EZH2 expression status and patient characteristics were evaluated using Fisher Exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. The independence of each of those associations from OSCC status was evaluated using Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test. Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analyses. The hazard ratios with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values were reported. All the analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1.3 software. All tests were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Paired t test was used for analysis of the in vitro studies.

RESULTS

Patients with OL

The study cohort consisted of 76 OL patients who had no prior cancer history from a single hospital. Among these patients, 37(49%) developed OSCC after the initial OL diagnosis, with median follow up time of 2 years, whereas 39 (51%) remained OSCC free with a median follow-up time of 11.4 years. The general characteristics of the patient population are presented in (Table 1 and supplementary Table).

Table 1.

Association between EZH2 Expression and Patient Characteristics

| EZH2 Expression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Weak (0–1) | Moderate (2) | Strong (3) | P | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| All patients | 76 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 34 | 34 | 45 | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 55.1 ± 13.6 | 52.4 ± 11.1 | 52.7 ± 13.6 | 58.1 ± 14.3 | .24 | |||

| Median | 53.5 | 53.5 | 51.5 | 59.0 | ||||

| Minimum, maximum | 25.0, 82.0 | 28.0, 76.0 | 25.0, 80.0 | 28.0, 82.0 | ||||

| Age group | ||||||||

| <60 years | 47 | 11 | 24 | 18 | 38 | 18 | 38 | .40 |

| ≥60 years | 29 | 5 | 17 | 8 | 28 | 16 | 55 | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 34 | 5 | 15 | 13 | 38 | 16 | 47 | .48 |

| Male | 42 | 11 | 26 | 13 | 31 | 18 | 43 | |

| Histology | ||||||||

| Dysplasia | 57 | 6 | 11 | 21 | 37 | 30 | 53 | <.001 |

| Other† | 19 | 10 | 53 | 5 | 26 | 4 | 21 | |

| Anatomic Site | ||||||||

| Low risk areas* | 31 | 11 | 35 | 9 | 29 | 11 | 35 | .04 |

| High risk areas* | 45 | 5 | 11 | 17 | 38 | 25 | 51 | |

| Smoking Status | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 | 4 | 28 | 5 | 36 | 5 | 36 | .45 |

| No | 51 | 8 | 16 | 17 | 33 | 26 | 51 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 4 | 36 | 4 | 36 | 3 | 28 | |

| Alcohol ConsumptionStatus | ||||||||

| Yes | 17 | 6 | 35 | 6 | 35 | 5 | 30 | .09 |

| No | 48 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 33 | 26 | 54 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 4 | 36 | 4 | 36 | 3 | 28 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P, p-value of the Kruskal-Wallis test for age as a numeric variable and that of Fisher’s Exact test for age group and other variables.

Other: Non dysplastic OL lesions ( Hyperkeratosis, Acanthosis, and Hyperplasia).

Low risk areas: buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, gingiva, and palate. High risk areas: floor of mouth, lateral and ventral tongue.

EZH2 expression and clinicopathological parameters

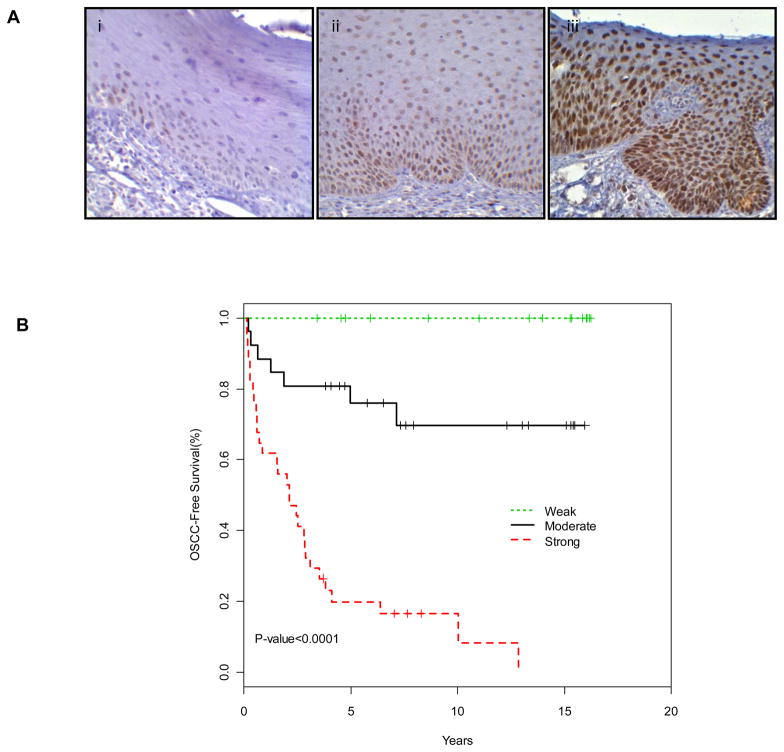

EZH2 expression was mainly observed as nuclear while cytoplasmic staining was observed in some cases. The intensity of EZH2 expression in the OLs ranged from negative to strongly positive and the extent of EZH2 expression varied from being limited only to the basal cell layer to being observed in full thickness of the epithelium (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. EZH2 expression and OSCC development.

(A) Immunohistochemical expression of EZH2 in OL tissue samples: Nuclear expression of EZH2 strongly correlated with the grade of dysplasia, the grade of dysplasia increasing from weak (i), moderate (ii) to strong (iii) (40x). (B) Kaplan Meier curves of OSCC-free survival based on EZH2 expression.

Among the OL lesions, 34 (45%) showed strong EZH2 staining, 26 (34%) showed moderate EZH2 staining, and 16 (21%) showed no or weak EZH2 staining (Table 1). EZH2 staining levels were strongly associated with the grade of dysplasia (P < .001) (Fig. 1A and Table 1). However, the expression of EZH2 was independent of dysplasia. (Table 1 and supplment Fig. 1).

EZH2 expression and OSCC development

To determine the role of EZH2 expression in OSCC development, we analyzed OSCC-Free survival probability which was defined as years from time of diagnosis of OL to time of diagnosis of OSCC, based on EZH2 expression in OLs. We found that EZH2 expression was strongly associated with OSCC-Free survival in an expression level dependent manner (P < .0001 by Log-Rank test; Fig. 1B). At 5-years, none of the 16 patients whose lesions showed no or weak EZH2 expression developed OSCC, whereas 6 (24%) of the moderate, and 28 (80%) of the strong EZH2 expressing OLs developed OSCC. Consistent with this, digital image analysis (Supplement Fig. 2), showed only 1 out of 15 lesions with weak EZH2 expression developed OSCC after 5 years of OL diagnosis (Supplement table 1). In the univariate analysis, we analyzed the association between the potential risk factors including EZH2 expression and OSCC development at 3-years and 5-years after OL diagnosis. EZH2 expression and OL histology were significantly associated with OSCC development (P <0.0001 and P <0.01, respectively; Table 2). Interestingly, alcohol use showed a borderline association with a reduced OSCC risk (P = 0.05). We then performed a multivariate analysis to include EZH2 expression, OL histology and alcohol use as co-factors. In this analysis (N=53), we found that EZH2 expression was the only independent factor significantly associated with OSCC development (P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

3-year and 5-year OSCC-Free survival rates by individual risk factor (N=76)

| Characteristic | 3-yr EFS | 5-yr EFS | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate (%)±SE | Rate (%)±SE | ||

| All patients | 63±6 | 56±6 | |

| EZH2 expression | |||

| Weak | 100±0 | 100±0 | <.0001 |

| Moderate | 81±8 | 76±9 | |

| Strong | 32±8 | 20±7 | |

| Age | |||

| < 60 | 66±7 | 59±7 | .28 |

| >=60 | 59±9 | 51±9 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 56±9 | 46±9 | .15 |

| Male | 69±7 | 64±7 | |

| Histology | |||

| Dysplasia | 56±7 | 46±7 | <.01 |

| Other | 84±8 | 84±8 | |

| Anatomic Site | |||

| Low risk areas | 68±8 | 68±8 | .17 |

| High risk areas | 60±7 | 48±8 | |

| Smoking Status* | |||

| Yes | 64±13 | 64±13 | .66 |

| No | 57±7 | 46±7 | |

| Unknown | |||

| Alcohol Status* | |||

| Yes | 76±10 | 76±10 | .05 |

| No | 52±7 | 41±7 | |

| Unknown | |||

Abbreviations: EFS, event free survival (OSCC-free survival); SE, standard error; P, p-value of the log-rank sum test overall.

There were 11 cases whose Smoking status and Alcohol consumption status unknown, for which the sample size is 65 instead of 76.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression models in estimating OSCC development

| Characteristic | P | Hazard ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 expression | |||

| Weak** | NA | NA | |

| Moderate | <.0001 | .17 | .07 to .41 |

| Strong | 1.00 | -- | |

| Histology | |||

| Dysplasia | .88 | 1.08 | .36 to 3.26 |

| Other | 1.00 | -- | |

| Alcohol status | |||

| No | .17 | 1.97 | .75 to 5.16 |

| Yes | 1.00 | -- | |

The Cox proportional hazards regression model excluded 23 cases that either missed alcohol status or had ‘weak’ as EZH2 expression level.

The hazard ratio for the Weak EZH2 expression group was not calculated because all cases in that group were censored.

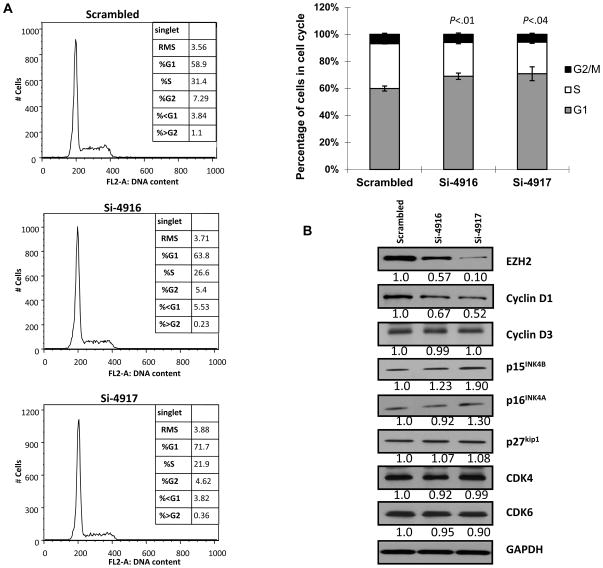

EZH2 and malignant features in OL cells

To explore the underlying mechanism by which EZH2 contribute to malignant transformation of OL cells, we used EZH2-siRNAs (si-4916 and si-4917) to specifically down-regulate EZH2 expression levels in an OL cell line, Leuk-1. At 72 h after EZH2-siRNA treatment, Leuk-1 cells showed reduced EZH2 levels and proliferation. The cells also showed an increased fraction of G1 phase (G1 arrest) with the decreased EZH2 level, in comparison to the cells treated with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 2A). In an effort to identify molecular mechanisms underlying the G1 cell cycle arrest by EZH2 down-regulation, we measured a panel of key proteins involved in G1 phase regulation. At 48 hours after EZH2-siRNA treatment, levels of cyclin D1 (CCND1) were significantly reduced while on the other hand, p15INK4B levels were increased (Fig. 2B). No change was observed for cyclin D3, p16 INK4A, p27 kip1, CDK4, and CDK6 expression levels (Fig. 2B). This data suggests that EZH2 may play a role in early oral tumorigenesis by promoting cell cycle progression through modulating p15 INK4B and CCND1.

Figure 2. EZH2 and cell cycle regulation in OL cells.

(A) Cell cycle analysis of Leuk-1 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti-EZH2 siRNA si-4916 and si-4917 for 72 h. (B) Cyclin D1 and p15INK4B expression in Leuk-1 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti-EZH2 siRNA si-4916 and si-4917 for 48 h.

Considering that EZH2 has been associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with OSCC (17, 18), we evaluated the effect of EZH2 in malignant transformation of Leuk-1 cells. The proliferation of Leuk-1 cells cultured on plastic surface was significantly reduced by the down-regulation of EZH2 level in a dose-dependent manner compared to the cells treated with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 3A). We then analyzed the effect of EZH2 down-regulation in anchorage-independent growth using soft agar colony formation assay. Leuk-1 cells treated with EZH2-siRNAs showed significantly reduced capability to form colonies in soft agar (Fig. 3B). Because CCND1 has been linked to malignant progression of oral premalignancy (21, 22), we investigated the possibility that EZH2 may promote invasion of Leuk-1 cells through modulating the expression of CCND1. EZH2-siRNA treated cells exhibited a significantly reduced invasion capability measured by a modified Boyden chamber invasion assay (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. EZH2 promotes malignant potential of Leuk-1 cells.

(A) Proliferation of Leuk-1 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti-EZH2 siRNA si-4916 and si-4917 for 72 h; (B) Colony formation of Leuk-1 cells (40x) transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti-EZH2 siRNA si-4916 and si-4917 (C) Invasion assay of Leuk-1 cells (100x) transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti-EZH2 siRNA si-4916 and si-4917 for 72 h.

DISCUSSION

A molecular-based model for OSCC development has been proposed in literature, which include deregulation of cell cycle proteins (23). CCND1 is one of the proteins that is frequently upregulated in oral premalignancies leading to malignant transformation and an increased risk of OSCC development (21, 22). Although CCND1 gene may be amplified in oral tumorigenesis, overexpression of CCND1 is also observed in OLs and OSCCs without the gene amplification (21). It has been reported that high EZH2 expression is associated with up-regulation of CCND1 in gastric cancer whereas the pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 leads to down-regulation of CCND1 levels in skin cancer (24, 25). Our observation that EZH2 down-regulation resulted in a decreased CCND1 expression level in OL cells is consistent with the previous reports and suggests that EZH2 is involved in CCND1 regulation in oral tumorigenesis.

In OLs and OSCC, p15INK4B promoter hypermethlation is frequently observed (26, 27). EZH2 may mediate this process through H3K27 trimethylation and recruitment of DNA methyltransferases (15, 28, 29). Consistent with this mechanism, we found increased p15INK4B level in OL cells when EZH2 is down-regulated. This provides additional support to the role EZH2 plays in oral tumorigenesis.

It is of particular interest to note that EZH2 can be activated by human papillomavirus (HPV) E7 oncoprotein in cervical tumorigenesis (30). Although the role of HPV in oral tumorigenesis has not been well established, HPV infection was casually linked to the development of oropharygneal squamous cell carcinoma in about 40% of the patients (31), suggesting HPV may be involved in early oral tumorigenesis (32). Thus, activation of EZH2 by HPV E7 in oral epithelial cell in oral tumorigenesis warrants further investigation.

The strong association between EZH2 expression in OLs and OSCC development is interesting and provocative. For practical reason, we analyzed OSCC incidences at 3 and 5 years after OL diagnosis to provide information regarding the potential impact of EZH2 as a predictive marker in OSCC risk assessment. Considering 80% of the patients with strong EZH2 expression OLs developed OSCC in 5 years whereas none with weak expression and 24% with moderate expression, EZH2 is one of the best single markers with potential to predict oral cancer risk for patients with OLs ever reported in literature (18, 33). It is important to note that EZH2 expression is associated with dysplasia histology but such association was dependent on EZH2 expression in terms of relationship with OSCC development as evidenced in our multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Contrary to most of the studies, we observed a borderline association between alcohol and tobacco use, and a reduced oral cancer risk in our patient population. Although this may be a result of the relatively small sample size, other factors might contribute to this observation. The population is from China where heavy smokers often drink liquor contains more than 50% alcohol regularly whereas the drinks consumed by most of the Westerners contain much lower concentrations of alcohol. It remains to be determined whether the higher alcohol concentration in Chinese drinks plays a different role in oral cancer development with or without tobacco exposure. Another possible contributing factor is the oral hygiene status of the population. Whether their oral microbial spectrum, which may also be influenced by smoking and drinking habits, impacts oral cancer development will need further investigation.

The use of sophisticated imaging equipment and software in pathological work have gained more use in the past several years. A comparison between the digital image analysis and semi-quantitative scoring indicate that the scores were most consistent in the weakly stained specimen, but differ more in the moderately and strongly stained specimen. Human semi-quantitative analysis clearly had the tendency to give more polarized score than the digital image analysis (supplement table 2). Importantly, despite the difference, the general conclusion in this study did not change.

The current study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective case-control study, which artificially enriched the proportion of patients who later developed OSCC and therefore may over estimate the predictive value of the biomarker. Second, the study is based on a Chinese population in a single hospital. Considering various genetic and environmental factors that can contribute to oral tumorigenesis, our findings in this population may have a limited implication in other populations at different geographic locations with various genetic backgrounds. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to validate these findings by using samples obtained prospectively in different geographic locations and from populations with various genetic backgrounds.

Nevertheless, in this study we identified, for the first time, that EZH2 expression is an independent predictor for OSCC development in patients with OLs and provided evidence to support the biological link between EZH2 and cell proliferation and invasion in OL cells. If validated in future studies, EZH2 may serve as a biomarker for oral cancer risk assessment of patients with OLs and a potential target for oral cancer chemoprevention (34).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work is supported in part by: Sir Kadoorie Foundation award to LM and WTC; WC is supported by a Doctoral Innovation Foundation from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and also Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project S30206 and Shanghai Science & Technology Commission grants 08JC1414400, 10DZ1951300 to WTC; RY is supported by the Egyptian cultural and educational bureau PhD scholarship and NIH postdoctoral training grant T32 DE007309-12.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi AC. Epithelial Pathology. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial pathology. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2009. pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53(3):563–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JJ, Hong WK, Hittelman WN, Mao L, Lotan R, Shin DM, et al. Predicting cancer development in oral leukoplakia: ten years of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):1702–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson PJ, Hamadah O, Goodson ML, Cragg N, Booth C. Predicting recurrence after oral precancer treatment: use of cell cycle analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(5):370–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eversole LR. Dysplasia of the upper aerodigestive tract squamous epithelium. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(1):63–8. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaaij-Visser TB, Bremmer JF, Braakhuis BJ, Heck AJ, Slijper M, van der Waal I, et al. Evaluation of cornulin, keratin 4, keratin 13 expression and grade of dysplasia for predicting malignant progression of oral leukoplakia. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(2):123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taoudi Benchekroun M, Saintigny P, Thomas SM, El-Naggar AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Ren H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene copy number in the risk of oral cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3(7):800–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao J, Zhou J, Gao Y, Gu L, Meng H, Liu H, et al. Methylation of p16 CpG island associated with malignant progression of oral epithelial dysplasia: a prospective cohort study. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5178–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha PK, Califano JA. Promoter methylation and inactivation of tumour-suppressor genes in oral squamous-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou ZT, Jiang WW. Cancer stem cell model in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3(1):17–20. doi: 10.2174/157488808783489426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon JA. Transcription. Sweet silencing. Science. 2009;325(5936):45–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1177264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho L, Crabtree GR. An EZ mark to miss. Cell. 2008;3(6):577–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valk-Lingbeek ME, Bruggeman SW, Van Lohuizen M. Stem cells and cancer; the polycomb connection. Cell. 2004;118(4):409–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viré E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439(7078):871–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breuer RH, Snijders PJ, Smit EF, Sutedja TG, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, et al. Increased expression of the EZH2 polycomb group gene in BMI-1-positive neoplastic cells during bronchial carcinogenesis. Neoplasia. 2004;6(6):736–43. doi: 10.1593/neo.04160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidani K, Osaki M, Tamura T, Yamaga K, Shomori K, Ryoke K, et al. High expression of EZH2 is associated with tumor proliferation and prognosis in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mut Res. 2008;647(1–2):21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren H, Tang X, Lee JJ, Feng L, Everett AD, Hong WK, et al. Expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor is a strong prognostic predictor for patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3230–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacks PG. Cell, tissue and organ culture as in vitro models to study the biology of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1996;15:27–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00049486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izzo JG, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Li XQ, Ibarguen H, Lee JS, Ro JY, et al. Dysregulated cyclin D1 expression early in head and neck tumorigenesis: in vivo evidence for an association with subsequent gene amplification. oncogene. 1998;17(18):2313–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akervall JA, Michalides RJ, Mineta H, Balm A, Borg A, Dictor MR, et al. Amplification of cyclin D1 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and the prognostic value of chromosomal abnormalities and cyclin D1 overexpression. Cancer. 1997;79(2):380–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan M, Migliorati CA, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Al-Hashimi I, Axéll T, et al. Management of oral epithelial dysplasia: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):S19. e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi JH, Song YS, Yoon JS, Song KW, Lee YY. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 expression is associated with tumor cell proliferation and metastasis in gastric cancer. APMIS. 2010;118(3):196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasubramanian S, Adhikary G, Eckert RL. The Bmi-1 polycomb protein antagonizes the (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-dependent suppression of skin cancer cell survival. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(3):496–503. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 26.Supić G, Kozomara R, Branković-Magić M, Jović N, Magić Z. Gene hypermethylation in tumor tissue of advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(12):1051–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeshima M, Saitoh M, Kusano K, Nagayasu H, Kurashige Y, Malsantha M, et al. High frequency of hypermethylation of p14, p15 and p16 in oral pre-cancerous lesions associated with betel-quid chewing in Sri Lanka. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(8):475–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agherbi H, Gaussmann-Wenger A, Verthuy C, Chasson L, Serrano M, Djabali M. Polycomb mediated epigenetic silencing and replication timing at the INK4a/ARF locus during senescence. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kheradmand Kia S, Solaimani Kartalaei P, Farahbakhshian E, Pourfarzad F, von Lindern M, Verrijzer CP. EZH2-dependent chromatin looping controls INK4a and INK4b, but not ARF, during human progenitor cell differentiation and cellular senescence. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland D, Hoppe-Seyler K, Schuller B, Lohrey C, Maroldt J, Dürst M, et al. Activation of the enhancer of zeste homologue 2 gene by the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9964–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1134. Erratum in: Cancer Res 2009;69(8):3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim L, King T, Agulnik M. Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology and public health implications. Oncology. 2010;24(10):915–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angiero F, Gatta LB, Seramondi R, Berenzi A, Benetti A, Magistro S, et al. Frequency and Role of HPV in the Progression of Epithelial Dysplasia to Oral Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(9):3435–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitiyage G, Tilakaratne WM, Tavassoli M, Warnakulasuriya S. Molecular markers in oral epithelial dysplasia: review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38(10):737–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sebova K, Fridrichova I. Epigenetic tools in potential anticancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21(6):565–77. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833a4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.