Abstract

Exposure of human monocytes-macrophages to anti-inflammatory agents, such as IL-10 or glucocorticoids, can lead to two separate fates: either Fas/CD95-mediated apoptosis or differentiation into regulatory and efferocytic M2c (CD14brightCD16+CD163+MerTK+) macrophages. We found that the prevalent effect depends on the type of T-helper cytokine environment and on the stage of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation. In particular, the presence of IFNγ (Th1 inflammation) or the prolonged exposure to IL-4 (chronic Th2 inflammation) promotes apoptosis of monocytes-macrophages and causes resistance to M2c differentiation, so provoking impaired clearance of apoptotic neutrophils, uncontrolled accumulation of apoptotic cells and persistent inflammation. By contrast, the presence of IL-17 (Th17 environment) prevents monocyte-macrophage apoptosis and elicits intense M2c differentiation, so ensuring efficient clearance of apoptotic neutrophils and restoration of anti-inflammatory conditions. Additionally, the T helper environment affects the expression of two distinct MerTK isoforms: IL-4 down-regulates the membrane isoform but induces an intracellular and Gas6-dependent isoform, whereas IFNγ down-regulates both and IL-17 upregulates both. Our data support an unexpected role for IL-17 in orchestrating resolution of innate inflammation, whereas IFNγ and IL-4 emerge as major determinants of IL-10 and glucocorticoid resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Innate inflammation is the first line of defense against microbes. Once the pathogen is removed or neutralized, a variety of mechanisms acts to down-regulate innate inflammation and protect tissues from uncontrolled chronic injury. Such mechanisms include apoptosis of monocytes-macrophages (1-4), switch of proinflammatory (classically activated) into regulatory (alternatively activated) macrophages (5-7), and apoptosis of activated neutrophils with subsequent phagocytosis (8-9). Recent data highlight that a discrete subset of alternatively activated (M2) macrophages, induced by glucocorticoids or by M-CSF plus IL-10 and called “M2c”, are importantly involved in resolution of innate inflammation, thanks to their unique ability to phagocytose early apoptotic neutrophils (ANs) and to release anti-inflammatory cytokines (5, 10-13). In particular, the upregulation of Mer receptor tyrosine kinase (MerTK) by these macrophages is crucial for intense efferocytosis and IL-10 production following apoptotic cell recognition and/or Gas6 stimulation (10-12, 14). Besides turning activated monocytes-macrophages into regulatory cells, another way to silence proinflammatory monocytes-macrophages is to induce their apoptosis. Some studies have shown that glucocorticoids and IL-10 also have pro-apoptotic effects on monocytes-macrophages (1-4). However, increased macrophage apoptosis may interfere with phagocytosis of ANs, and so contribute to further accumulation of apoptotic bodies. As such, macrophage apoptosis can be detrimental for resolution of innate responses; indeed, it can stimulate abnormal adaptive responses and development of autoimmunity (15).

Optimal resolution of innate inflammation also depends on the fate of dying neutrophils recruited into inflamed tissues. In particular, early apoptosis of activated/aged neutrophils promotes resolution, by inhibiting further neutrophil oxidative burst and the release of proinflammatory mediators, and by eliciting regulatory pathways in efferocytic macrophages (8-10). Regulatory pathways can also be induced by neutrophil release of ectosomes, which stimulate macrophage production of anti-inflammatory cytokines following MerTK-mediated recognition of phosphatidilserine exposed on their surface (16). By contrast, some alternative fates of activated neutrophils can fuel ongoing inflammation, such as late apoptosis (secondary necrosis) and a newly described form of programmed cell death called NETosis (9, 17). Both secondary necrosis and NETosis generate extracellular release of chromatin and proteases, which may act as danger signals and supply antigenic material fostering chronic activation of immune system, uncontrolled tissue damage, and development of autoimmunity (18-25). Late apoptosis results from impaired clearance of early membrane-intact apoptotic cells (19, 26), as occurs in the presence of macrophages with low or absent MerTK expression (10, 18). Whether a prompt clearance of early ANs can also have a role in preventing NETosis remains to be determined. Altogether, multiple mechanisms aimed at resolving innate inflammation utilize MerTK to enhance regulatory activity of anti-inflammatory macrophages and to transmit regulatory signals from activated and dying neutrophils to surrounding macrophages. M2c polarization and MerTK induction lead to non-inflammatory clearance of activated neutrophils and homeostatic control of innate immunity, whereas macrophage apoptosis and impaired clearance of early ANs exacerbate immune responses.

Activation of innate immune cells during disease occurs within a discrete immunopathological context, depending on polarization of adaptive immune response. In the present study, we investigated the specific influences of T helper (Th) cytokines on macrophage responsiveness to M2c polarizing agents (IL-10 and glucocorticoids), in terms of monocyte-macrophage apoptosis, M2c macrophage differentiation, MerTK induction and phagocytosis of ANs. We found that IL-17 strongly amplifies M2c differentiation and MerTK-dependent clearance of neutrophils, whereas IFNγ and chronic exposure to IL-4 induce Fas/CD95-mediated apoptosis of monocytes-macrophages and uncontrolled accumulation of apoptotic neutrophils. Furthermore, the Th environment affects differential expression of surface and intracellular MerTK isoforms. Results suggest that the Th17 environment promotes successful resolution of innate inflammation by glucocorticoids and IL-10, whereas Th1 and chronic Th2 diseases may be resistant to therapies aimed at control of innate immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures

Monocytes from buffy coats of healthy blood donors were isolated by Ficoll-Paque™ Plus gradient (GE Healthcare) and magnetic separation, using a kit for human monocyte enrichment by negative selection (EasySep™, StemCell), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Purity of CD14+ cells was > 90%, as assessed by flow cytometry. CD14+ cells were cultured for 8 days in 24-well plates at 0.8×106 cells/ml at 37°C in 5% CO2 in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% human AB serum, L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin. Cell treatments included: IFNγ (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems); IL-4 (20 ng/ml; Novus Biologicals); IL-17 (100 ng/ml; R&D Systems); GM-CSF (100 ng/ml; Peprotech); M-CSF (50 ng/ml; Peprotech); LPS (from E. Coli 026:B6, 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Dexamethasone (100 nM; Sigma-Aldrich) was given to cultured monocytes on d 0, or to differentiated macrophages on d 5, as specified in the text. IL-10 (50 ng/ml; Peprotech) was added on d 5. To measure the exact amounts of Gas6 released by cultured cells in supernatants, some experiments were performed in serum-free conditions. For these experiments, cells were cultured at 0.8×106 cells/ml in X-Vivo™15 medium (Lonza) for 4 days, and incubated with one or more treatments from d 0. Prior to participation, all subjects gave informed consent to donate their blood samples. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Temple University.

Flow cytometry

Phenotypic analysis was carried out in cultured monocytes-macrophages, after washing in buffer containing 2% bovine serum albumin. The following mouse monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-CD14 (PE-Cy7), anti-CD163 (APC or PerCP-Cy5.5), anti-CD206 (APC-Cy7), anti-CD209 (PerCP-Cy5.5), anti-CD95 (APC or FITC) (Biolegend); anti-CD16 (APC-Cy7) (BD Biosciences); anti-CD204 (APC) and anti-MerTK (clone 125518; PE) (R&D Systems). MerTK expression was evaluated using appropriate PE-labeled isotype control (Biolegend). Cells were analyzed using FACSCalibur™ (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software.

Western blot

Cell lysates were obtained in buffer containing 50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and freshly added cocktails of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were resolved on a SDS-PAGE 8% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), were probed with biotinylated goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK (R&D Systems), mouse monoclonal anti-CD95 (BD Biosciences), or rabbit anti-β-actin antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were then incubated, as appropriate, with horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (Biolegend), secondary donkey anti-mouse (Pierce) or goat anti-rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Immunoblots were developed and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using Amersham ECL™ reagents (GE Healthcare).

Induction of apoptosis and phagocytosis assay

Human neutrophils were isolated from Ficoll-Hypaque pellets through dextran erythrocyte sedimentation and lysis of contaminating erythrocytes by incubation with ice-cold ammonium chloride (0.15 M) and potassium bicarbonate (0.01 M) solution. Neutrophils were resuspended at 1×106 cell/ml in 10% FBS-RPMI, labeled with 2.5 μM CFSE (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 20 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. APC-conjugated annexin V (BD Biosciences) and propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich) were used to measure apoptosis by flow cytometry. The composition of neutrophils routinely obtained after incubation was: 71.7±14.1% early ACs (annexinV+PI−), 4.3±2.0% late ACs (annexinV+PI+), 0.4±0.2% necrotic cells (annexinV-PI+). ANs were added for 30 minutes to cultured macrophages, at a 5:1 ratio. Flow cytometry was used to quantify percentages of CD14-labeled macrophages that phagocytosed CFSE-labeled ACs. For inhibition studies, macrophages were pre-incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK antibody (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems) or a goat polyclonal control IgG (5 μg/ml; SouthernBiotech) for 30 minutes before adding ANs.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cultured macrophages were stained in 24-well plates using a FITC-conjugated anti-CD95 antibody (Biolegend) and a biotinylated mouse monoclonal anti-CD16 antibody (Ancell), followed by incubation with Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (Biolegend). Cells were viewed under a Leica DMI6000B inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica), controlled by Slidebook software.

ELISA

Gas6 levels were measured in supernatants of 4-day cell cultures in serum-free conditions, using sandwich ELISA according to standard procedure (27). Standard curves were prepared with rhGas6 (R&D Systems). Purified goat anti-human Gas6 antibody (R&D Systems) was used for capture. Biotinylated goat polyclonal anti-human Gas6 antibody (R&D Systems), followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Biolegend), was used for detection.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Statistical significance among different cell treatments was assessed by Student’s paired t-test, or one-way repeated measures ANOVA if treatment groups were more than two. Statistical significance was defined as P <0.05. Analysis and graphing were performed using GraphPad Prism™ software.

RESULTS

Macrophage response to IL-10: IL-17, but not IFNγ or IL-4, elicits M2c differentiation and MerTK-dependent efferocytosis

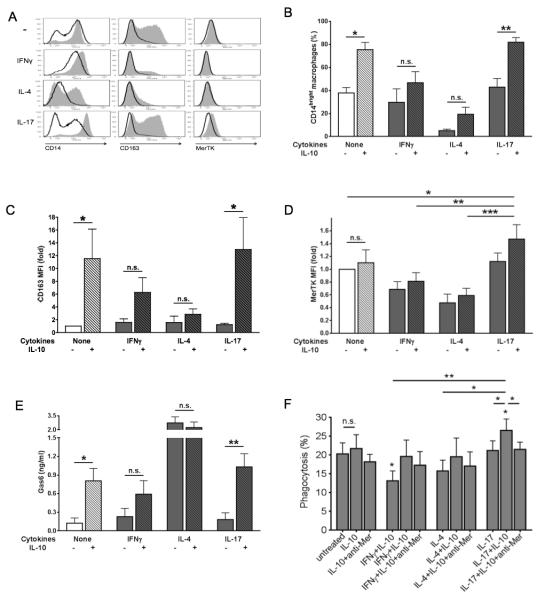

We examined the susceptibility of untreated (“M0”), IFNγ-conditioned (M1), IL-4-conditioned (M2a) and IL-17-conditioned (hereafter called “M17”) macrophages to switch into M2c (CD14brightCD163+MerTK+) cells in response to IL-10. We found that IL-10 effects on macrophage polarization were significantly enhanced by IL-17. Although detectable, IL-10 effects were weak and/or did not reach full statistical significance in the absence of IL-17. Along with a potent induction of CD163, the combination of IL-17 plus IL-10 induced the highest levels of CD14, and was able to upregulate MerTK (Fig. 1A-D). By contrast, both IFNγ and IL-4 inhibited M2c response, preventing IL-10 induction of CD163, CD14 and MerTK on the cell surface (Fig. 1A-D). Analogous results were obtained whether IL-10 was added from d 5 to already differentiated M1, M2a or M17 macrophages, as a polarizing agent (Fig. 1A), or from d 0 to cultured monocytes together with IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17, as a differentiating agent (Fig. 1B-D). In the presence of IL-17, IL-10 also induced greater secretion of the MerTK ligand Gas6 compared to IL-10 alone (Fig. 1E). In accord with our previous results (10), IL-4 induced high levels of Gas6, but in this case the addition of IL-10 exerted no additive effect (Fig. 1E). Subsequently, we analyzed the ability of M0, M1, M2a and M17 macrophages to phagocytose ANs following exposure to IL-10. Consistent with MerTK expression pattern, IL-10 significantly increased phagocytosis of ANs only in M17 cells, and this effect was abrogated in the presence of an anti-MerTK blocking antibody (Fig. 1F). Detection of phenotype markers and quantification of phagocytosis were not altered by macrophage autofluorescence, which was absent or negligible in our experimental conditions (Supp. Fig. 1). These data indicate that IL-17, but not IFNγ or IL-4, potentiates the anti-inflammatory response of human macrophages to IL-10, resulting in more intense M2c polarization, greater secretion of Gas6, and enhanced clearance of ANs via MerTK.

Figure 1. Macrophage response to IL-10: IL-17, but not IFNγ or IL-4, elicits M2c differentiation and MerTK-dependent efferocytosis.

(A) Human monocytes were sorted from healthy PBMCs through negative selection magnetic beads and cultured in complete medium without cytokines (M0 differentiation), or in the presence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml; M1 differentiation), IL-4 (20 ng/ml; M2a differentiation) or IL-17 (100 ng/ml; M17 differentiation). On day 5, cells were treated with IL-10 (50 ng/ml) for an additional 3 days (M2c polarization). Grey histograms, cells cultured with IL-10; white histograms, cells cultured without IL-10. Expression of the M2c markers CD14, CD163 and MerTK was measured by flow cytometry. (B-E) To measure autocrine production of Gas6 along with surface expression of M2c markers, cells were cultured for 4 days in serum-free medium with IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17, in the presence or absence of IL-10. Expression levels of CD14 (B), CD163 (C), and MerTK (D) were assessed by flow cytometry and depicted as percentages of CD14bright cells or mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) fold variation compared to levels obtained with culturing cells without IL-10. Gas6 levels (E) in culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Data are representative of four independent experiments. (F) Early ANs were obtained by incubating healthy human neutrophils in 10% FBS-RPMI for 20 hours. CFSE-labeled ANs were added for 30 minutes, at a 5:1 ratio, to CD14-labeled macrophages differentiated for 7-8 days in complete medium without cytokines or in the presence of IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17, with or without IL-10 in the last 3 days. For inhibition studies, macrophages were pre-incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK antibody (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems) for 30 minutes before the addition of ANs. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001; n.s., not significant.

IL-4 impedes IL-10 differentiation of M2c macrophages, but induces Gas6 and a 150-KDa intracellular MerTK isoform

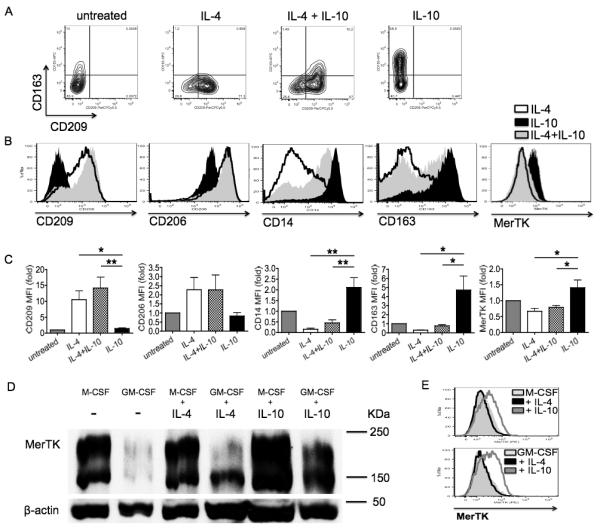

IL-4 and IL-10 are both considered major anti-inflammatory cytokines. However, they induce different types of M2 macrophages, namely M2a for IL-4 (CD206+CD209+) and M2c for IL-10 (CD163+) (5, 10, 28). We examined the effects of combining IL-4 and IL-10 on macrophage phenotype. We found that IL-4 is dominant over IL-10. The great majority of cells incubated with both cytokines were in fact CD209+, including a minor population of double positive CD209+CD163+ cells, whereas very few cells were single positive for CD163 (Fig. 2A). In the co-presence of IL-4 and IL-10, CD209 expression was even enhanced compared to cells treated with IL-4 alone, whereas CD206 was unchanged (Fig. 2B-C); conversely, membrane expression of the M2c receptors CD163, CD14 and MerTK was significantly decreased compared to IL-10 alone (Fig. 2B-C). As we showed above (Fig. 1E), both IL-10 and IL-4 stimulated Gas6 secretion. This is in apparent contradiction with IL-4 inhibition of the surface 200-KDa MerTK isoform (11). Since prolonged Gas6 stimulation was recently found to induce a poorly glycosylated intracellular isoform of MerTK with lower molecular weight (150 KDa) (31), we investigated whether IL-4, as well as IL-10, might still upregulate the Gas6-dependent isoform. To facilitate the potential detection of this minority glycoform, we increased exposure time of Western blots (up to 30 minutes); in addition, we cultured cells with macrophage growth factors (M-CSF or GM-CSF) to prolong times of culture and therefore Gas6 exposure. In particular, because GM-CSF down-regulates MerTK (10), it was used to decrease MerTK background levels at baseline in order to increase the contrast for potential new bands upon IL-4 or IL-10 treatment. Ultimately, we were able to clearly detect IL-4 specific induction of the 150-KDa MerTK isoform; IL-10 was able to upregulate both 200-KDa and 150-KDa isoforms (Fig. 2D). The 150-KDa isoform was not detectable on the cell surface, as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2E). These studies show that IL-4 exerts dominant effects on the M2 macrophage phenotype, impeding IL-10 induction of M2c cells. Although M2a macrophages do not express MerTK on their surface, they still express Gas6 and an intracellular 150-KDa MerTK glycoform.

Figure 2. IL-4 impedes IL-10 differentiation of M2c macrophages, but induces Gas6 and a 150-KDa intracellular MerTK isoform.

(A-C) Macrophages were differentiated for 8 days in complete medium plus IL-4 (20 ng/ml; M2a differentiation), IL-10 (50 ng/ml; M2c differentiation), or both cytokines from day 3 for 5 days. Expression levels of CD163, CD209, CD206, CD14 and MerTK was assessed by flow cytometry, and depicted in (C) as MFI fold variation compared to levels obtained with culturing cells without any cytokine. (D-E) To increase the number of terminally differentiated macrophages on day 8 and clearly detect a minor MerTK isoform, macrophages were differentiated in the presence of growth factors M-CSF (50 ng/ml) or GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) from day 0, adding IL-4 or IL-10 on day 3 for an additional 5 days. A 150-KDa (intracellular) MerTK isoform was observed by Western blot. The 200-KDa (surface) MerTK isoform was detected by both Western blot (D) and flow cytometry (E). Data are representative of three independent experiments. Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01.

Early response to glucocorticoids: IL-17 and IL-4, but not IFNγ, allow differentiation of M2c MerTK-dependent efferocytic macrophages

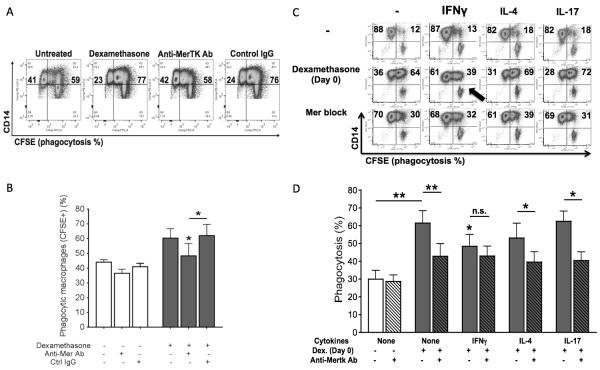

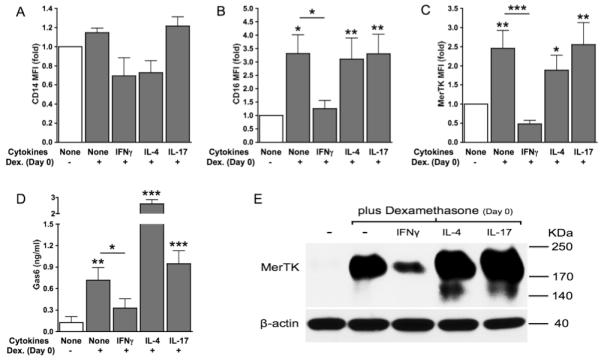

We examined the susceptibility of M0, M1, M2a and M17 macrophages to switch into M2c cells in response to glucocorticoids. For this purpose, we cultured monocytes in the presence or absence of IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17, with or without dexamethasone from d 0. We found that dexamethasone induced an M2c phenotype in all cell populations except for M1 macrophages. IFNγ lowered expression levels of CD14 (Fig. 3A) and significant suppressed the M2c marker CD16/FcγRIII (Fig. 3B). Lower expression of other M2c receptors (e.g., CD204, CD163) was also observed (not shown). Additionally, IFNγ-treated cells were refractory to glucocorticoid upregulation of MerTK (Fig. 3C) and Gas6 (Fig. 3D). By Western blot, we observed dexamethasone specific induction of the 200-KDa MerTK isoform, and confirmed IFNγ inhibition of MerTK (Fig. 3E). In line with higher levels of Gas6 in supernatants (Fig. 3F), cell treatments with dexamethasone in the presence of IL-4 or IL-17 resulted in the upregulation of the intracellular 150-KDa MerTK isoform (Fig. 3E). Subsequently, we tested dexamethasone effects on phagocytosis of ANs by M0, M1, M2a and M17 macrophages. For inhibition studies, we used a goat polyclonal anti-MerTK neutralizing antibody, whose specificity was preliminarily verified by comparing its effects with those exerted by a goat polyclonal control IgG (Fig. 4A-B). Consistent with IFNγ resistance to glucocorticoid induction of MerTK (Fig. 3), cells cultured with IFNγ plus dexamethasone showed significantly lower clearance of ANs compared to macrophages differentiated in the presence of dexamethasone alone or dexamethasone plus IL-4 or IL-17 (Fig. 4C-D). Moreover, glucocorticoid induction of efferocytosis by M1 cells was not dependent on MerTK. By contrast, dexamethasone effects on efferocytosis by M0, M2a and M17 were significantly reduced by the addition of an anti-MerTK blocking antibody (Fig. 4C-D). These data indicate that a Th1 environment promotes monocyte resistance to differentiation into anti-inflammatory and efferocytic macrophages in response to early glucocorticoid treatment. By contrast, Th2 or Th17 conditions allow optimal glucocorticoid differentiation of monocytes into MerTK+ M2c cells.

Figure 3. Early response to glucocorticoids: IL-17 and IL-4, but not IFNγ, allow M2c differentiation and MerTK/Gas6 induction.

Monocytes were cultured for 4 days in serum-free medium with or without dexamethasone from day 0 (100 nM; M2c differentiation), in the presence or absence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml) or IL-17 (100 ng/ml). Expression levels of CD14 (A), CD16 (B), MerTK (C) were measured by flow cytometry and depicted as MFI fold variation compared to untreated cells. Gas6 levels (D) in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Expression of 200-KDa and 150-KDa MerTK isoforms (E) was assessed by Western blot. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001.

Figure 4. Early response to glucocorticoids: IL-17 and IL-4, but not IFNγ, allow differentiation of MerTK-dependent efferocytic macrophages.

CFSE-labeled ANs were added for 30 minutes, at a 5:1 ratio, to CD14-labeled macrophages differentiated for 7-8 days in complete medium with or without dexamethasone from day 0 (100 nM; M2c differentiation), in the presence of absence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml) or IL-17 (100 ng/ml). For inhibition studies, macrophages were pre-incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK antibody (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems) for 30 minutes before the addition of ANs. Specificity of anti-MerTK antibody was preliminarily assessed by comparing its effects with those exerted by a goat polyclonal control IgG (5 μg/ml; SouthernBiotech). All data shown are representative of four independent experiments. Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; n.s., not significant.

Late response to glucocorticoids: IL-17, but not IFNγ or IL-4, promotes MerTK-dependent efferocytosis by terminally differentiated macrophages

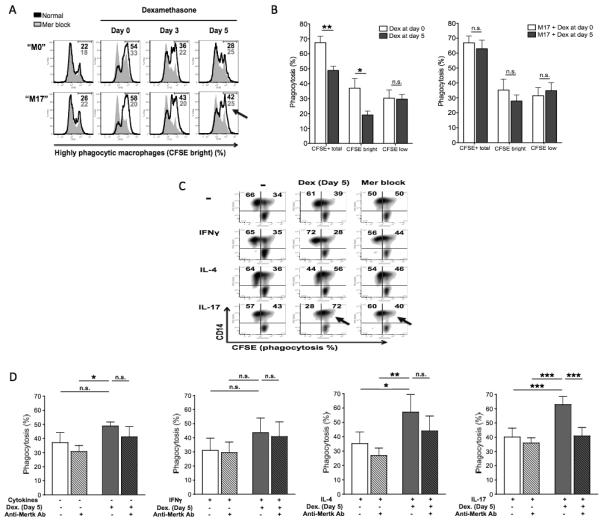

The first 24 hours of culture are critical for glucocorticoid-mediated augmentation of AC clearance by macrophages (30). We observed, in fact, that the addition of dexamethasone at later stages of macrophage differentiation (from d 3 or d 5) gave a weaker stimulation of efferocytosis compared to dexamethasone treatment from d 0; phagocytic activity progressively decreased as glucocorticoid treatment was delayed (Fig. 5A). Strikingly, in the presence of IL-17, the glucocorticoid promotion of efferocytosis was instead preserved over time. When dexamethasone was given from d 5, IL-17 was able to rescue dexamethasone induction of highly efferocytic (CFSEbright) cells, causing an effect analogous to what was seen with early glucocorticoid treatment (Fig. 5A-B). By contrast, in the absence of IL-17, CFSEbright macrophages were significantly fewer than with early glucocorticoid treatment (Fig. 5B). Addition of dexamethasone from d 5 did not result into a clear-cut augmentation of total efferocytic (CFSE+) macrophages (Fig. 5C-D). Similar results were obtained in the presence of IFNγ (Fig. 5C-D). IL-4 facilitated glucocorticoid-induced efferocytosis, yet this was independent of MerTK activity (Fig. 5C-D). Remarkably, IL-17-differentiated macrophages exhibited the greatest response to dexamethasone, and M17 phagocytosis of ANs was significantly abrogated by blocking MerTK (Fig. 5C-D). These results indicate that a Th17 environment uniquely disposes terminally differentiated macrophages to highly efficient clearance of ANs in response to glucocorticoid treatment, by rescuing and amplifying M2c differentiation and MerTK induction.

Figure 5. Late response to glucocorticoids: IL-17, but not IFNγ or IL-4, promotes MerTK-dependent efferocytosis by terminally differentiated macrophages.

(A-B) Macrophages were differentiated for 8 days in complete medium in the presence or absence of IL-17 (100 ng/ml). Dexamethasone was added from day 0 (M2c differentiation) or during monocyte-to macrophage differentiation, from day 3 or from day 5. CFSE-labeled ANs were then coincubated with CD14-labeled macrophages, at a 5:1 ratio, for 30 minutes. Among macrophages, in (A) we could distinguish non-efferocytic CFSEnull macrophages (left peak), moderately efferocytic CFSElow macrophages (central peak) and highly efferocytic CFSEbright macrophages (right peak). Numerical values refer to percentages of CFSEbright macrophages. Grey peaks refer to assays performed in the presence of a goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK blocking antibody (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems), added for 30 minutes prior to macrophage coincubation with ANs. CFSEtotal macrophages in (B) refers to total efferocytic (CFSEbright plus CFSElow) macrophages. (C-D) Cells were cultured in complete medium with no cytokines (M0 differentiation), or in the presence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml; M1 differentiation), IL-4 (20 ng/ml; M2a differentiation) or IL-17 (100 ng/ml; M17 differentiation); from day 5, cells were treated with dexamethasone (100 nM) for an additional 3 days (M2c polarization). CFSE-labeled ANs were then coincubated with CD14-labeled macrophages, at a 5:1 ratio, for 30 minutes. For inhibition studies, macrophages were pre-incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-human MerTK antibody (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems) for 30 minutes before the addition of ANs. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001; n.s., not significant.

To exclude that our results might have been conditioned by potential endotoxin contamination of reagents, we conducted control experiments looking at the effects of IL-10 and dexamethasone on macrophage phenotype and phagocytosis of ANs in the presence or absence of LPS. LPS did not significantly affect macrophage response to IL-10 and dexamethasone, added either on d 0 or on d 5 (Supp. Fig. 2).

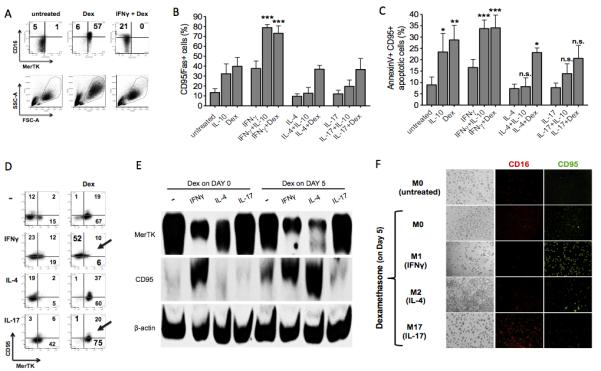

Response to IL-10 and glucocorticoids: IL-17, but not IFNγ o r IL-4, protects macrophages from CD95 upregulation and apoptosis

We explored the effect of IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17 on monocyte susceptibility to apoptosis following exposure to glucocorticoids or IL-10. Resistance of IFNγ cultured cells to glucocorticoid induction of MerTK and M2c markers such as CD16 was associated with unchanged cell morphology upon treatment, as indicated by unmodified forward and side scatter at flow cytometry (Fig. 6A). In the presence of IFNγ, indeed, either glucocorticoids or IL-10 significantly induced Fas/CD95 expression (Fig. 6B) and apoptosis, as assessed by increased proportions of CD95+AnnexinV+ cells (Fig. 6C). Propidium iodide staining, indicative of cell death by necrosis, was instead negative (not shown). Dexamethasone upregulation of CD95 was inversely related to MerTK induction (Fig. 6D-E). Specifically, the presence of IFNγ allowed CD95 upregulation and prevented MerTK expression, whereas the presence of IL-17 allowed MerTK upregulation and prevented CD95 expression (Fig. 6D-F). The presence of IL-4 variably influenced glucocorticoid responses depending on the stage of macrophage differentiation: early dexamethasone administration allowed MerTK upregulation (Fig. 6D-E), whereas late administration increased CD95 expression and prevented MerTK induction (Fig. 6E). As for MerTK, an inverse relationship with CD95 expression was found for the expression pattern of M2c markers such as CD16 (Fig. 6F). These data indicate that M2c macrophage differentiation and macrophage apoptosis upon glucocorticoid or IL-10 stimulation are mutually exclusive responses, and that the final effect is primarily influenced by the T-helper cytokine environment and by the timing of cell stimulation. Th1 and protracted Th2 environments program monocytes-macrophages to respond to anti-inflammatory treatments by undergoing apoptosis, thereby preventing MerTK expression and phagocytosis of ANs. By contrast, the Th17 environment constantly protects macrophages from apoptosis, and elicits active resolution of macrophage inflammation with non-inflammatory clearance of ANs.

Figure 6. Response to IL-10 and glucocorticoids: IL-17, but not IFNγ o r IL-4, constantly protects macrophages from CD95 upregulation and apoptosis.

(A) Cells were cultured for 4 days in serum-free medium with or without dexamethasone from day 0 (100 nM; M2c differentiation), in the presence or absence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml). Panels representing CD16 and MerTK expression, along with panels representing Side Scatter (SSC) and Forward Scattor (FSC) are shown. Data shown are representative of four independent experiments. (B-D) Cells were cultured for 3 days in complete medium in the presence or absence of IFNγ (10 ng/ml; M1 differentiation), IL-4 (20 ng/ml; M2a differentiation) or IL-17 (100 ng/ml; M17 differentiation), with or without IL-10 (50 ng/ml) or dexamethasone (100 nM) from day 0. Apoptosis of monocytes-macrophages was assessed by flow cytometry using CD95 (B-D), annexin V (C) and propidium iodide (not shown) stainings. Data are representative of four independent experiments. (E-F) Macrophages were differentiated for 8 days in complete medium in the presence or absence of IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17; dexamethasone was added to some cell cultures from day 5. Expression of markers of macrophage apoptosis (CD95) and M2c polarization (MerTK, CD16) was assessed by Western blot (E) and fluorescence microscopy (F). Pooled data are represented as mean values ± SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001; n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

Macrophages are, at once, the main effectors and regulators of innate inflammation. Due to macrophage plasticity, intervention of anti-inflammatory agents in the microenvironment can promptly shift macrophages from proinflammatory to regulatory suppressive cells (10, 31). In the present study, we show that the response of human monocytes and macrophages to anti-inflammatory mediators is dramatically influenced by polarization of the coexisting adaptive response. The presence in the microenvironment of the Th cytokines IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-17 has crucial effects on the overall outcome of monocyte-macrophage exposure to IL-10 and glucocorticoids, in terms of regulatory M2c macrophage differentiation, macrophage phagocytosis of ANs, or monocyte-macrophage apoptosis. Due to dynamic changes of immunological environment during in vivo inflammation, the study was conducted on well-determined macrophage subsets obtained after in vitro polarization. The main findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Differentiation of M2c regulatory macrophages (CD14, CD16, CD163) and phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils (MerTK) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | Early GCs (day 0) | Late GCs (day 5) | |

| M0 | +/− | +++ | +/− |

| M1 | - | - | - |

| M2a | - | +++ | - |

| M17 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

|

| |||

| Apoptosis of monocytes-macrophages (CD95) and accumulation of apoptotic neutrophils |

|||

| IL-10 | Early GCs (day 0) | Late GCs (day 5) | |

| M0 | +/− | +/− | +++ |

| M1 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| M2a | - | +/− | +++ |

| M17 | - | - | - |

Effects on M2c differentiation, MerTK expression and apoptosis exerted by IL-10 and early or late glucocorticoid administration on human macrophages differentiated in the absence of cytokines (M0), or in the presence of IFNγ (M1), IL-4 (M2a) or IL-17 (M17). GCs, glucocorticoids; “+++” significant effects; “+/−” partial effects; “-” no effects.

We found that IFNγ/Th1 environment makes monocytes-macrophages highly resistant to M2c polarization and phagocytosis of ANs. In this regard, Heasman and collegues previously reported IFNγ inhibition of glucocorticoid augmentation of apoptotic cell clearance; however, these authors failed to elucidate the mechanisms of such phenomenon (32). Here, we determined that IFNγ potently inhibits glucocorticoid and IL-10 differentiation of human monocytes into regulatory M2c (CD14brightCD16+CD163+MerTK+Gas6+) macrophages; similarly, terminally IFNγ differentiated M1 macrophages do not switch into M2c cells upon treatment. M2c macrophages are, in fact, a subset of alternatively activated macrophages (5) that we recently characterized as highly specialized in the clearance of early (membrane-intact) apoptotic cells due to intense MerTK upregulation (10). ANs maintain their intact membranes longer than most other apoptotic cells (9) and, consistently, MerTK has been shown to play a central role in their clearance (33).

In the presence of IFNγ, monocytes-macrophages show abnormal responses to IL-10 and glucocorticoids: instead of differentiating into M2c cells, they upregulate the proapoptotic receptor Fas (CD95) and undergo apoptosis. Increased apoptosis may explain impaired M2c differentiation and efferocytosis; alternatively, since MerTK exerts an important anti-apoptotic role in macrophages (34), it is also possibile that defective MerTK expression promotes apoptosis. IL-4/Th2 environment allows glucocorticoids to differentiate monocytes into M2c macrophages; however, terminally IL-4 differentiated M2a macrophages are refractory to switching into M2c cells in response to either glucocorticoids or IL-10. Similarly to IFNγ, chronic exposure to IL-4 results, instead, in down-regulation of MerTK and M2c receptors and increased expression of CD95. By inducing monocyte-macrophage apoptosis and preventing phagocytosis of ANs, IFNγ and IL-4 may promote autoimmune responses. In fact, coincubation of serum from lupus patients with healthy macrophages induces macrophage apoptosis (26), and eliciting macrophage apoptosis exacerbates autoimmunity in lupus models (15). Besides, in lupus and other chronic inflammatory diseases, impaired clearance of early ANs accounts for late apoptosis, tissue damage and aberrant immune activation (17-20, 24, 26).

Th1 and chronic Th2 inflammation may represent major determinants of macrophage resistance to the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 and glucocorticoids. In the presence of IFNγ and IL-4, IL-10 may have roles different from M2c polarization and immune suppression: in Th1 diseases and lymphoproliferative disorders, as well as in organ rejection, IL-10 may cooperate with IFNγ in promoting expansion of B and/or NK cells (7); in chronic Th2 diseases and fibrotic disorders, IL-10 may enhance IL-4 induction of remodeling M2a macrophages (36-37).

Resistance to glucocorticoids is frequently observed in clinical practice (38). Several IFNγ-mediated pathologies, including atherosclerosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome or many cases of IBD, have poor or no response to glucocorticoids (39-41); similarly, refractory or relapsing forms of vasculitis show persistent elevation of IFNγ levels in tissues despite glucocorticoid treatment (42). IL-4 overexpression is involved in glucocorticoid resistance of several chronic Th2 diseases characterized by impaired apoptotic cell clearance and fibrotic remodeling, such as chronic asthma, COPD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (20-21, 38, 43-44); also, glucocorticoid-resistant asthma is associated with local production of IFNγ (45). Our data provide new insights into the mechanisms of IL-10 and glucocorticoid resistance in these diseases, showing that IFNγ and IL-4 strongly inhibit the expansion of M2c regulatory macrophages, so preventing efficient efferocytosis and restoration of anti-inflammatory conditions. From this view, glucocorticoid-resistant airway fibrotic remodeling may reflect refractoriness of fibrogenic M2a macrophages to M2c polarization. Strikingly, IL-17/Th17 environment significantly amplifies the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 and sustains macrophage susceptibility to glucocorticoids. Facilitation of M2c polarization by IL-17 is associated with macrophage protection from CD95 upregulation and apoptosis; this is consistent with the previous demonstration in a mouse model of allergen-induced airway inflammation that IL-17 inhibits CD95 expression and prolongs survival of bronchoalveolar macrophages (46). To date, IL-17 has been identified as a proinflammatory cytokine importantly involved in immune responses against infections (47), in chronic inflammation and in autoimmunity (48-49). Nonetheless, recent studies suggest that IL-17 effects are more complex than what was initially believed. In fact, IL-17 not only stimulates granulopoiesis and neutrophil recruitment to sites of inflammation (49-51), but also promotes neutrophil apoptosis (52-54) and macrophage phagocytosis of ANs (54). Thus, IL-17 could orchestrate multiple steps in acute inflammation, including its resolution once the triggering agent has been neutralized. Silverpil et al. (54) recently reported that IL-17 is able to stimulate phagocytosis of ANs by murine bronchoalveolar macrophages. In humans, instead, we found that IL-17 is not per se responsible for phagocytosis, but it significantly amplifies and prolongs IL-10 and glucocorticoid induction of phagocytosis. It is noteworthy, however, that Silverpil et al. (54) primed macrophages with LPS before IL-17 administration; therefore, autocrine production of IL-10 induced by LPS (55) could have allowed macrophage exposure to IL-17 and IL-10 in combination. Intervention of IL-10 in the microenvironment is probably required to convert IL-17 from a proinflammatory to a regulatory molecule. The coexistence of IL-17 and IL-10, in fact, disposes innate immune cells to restore anti-inflammatory conditions. IL-10 alone is poorly effective on otherwise untreated M0 macrophages, whereas IL-17 enables M17 macrophages to respond to IL-10 efficiently, in terms of M2c polarization, MerTK expression, Gas6 production and M2c-related phagocytosis of ANs via MerTK. Our findings are consistent with previous data reporting the efficient role of IL-10 in suppressing production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages exposed to IL-17 (56). The presence of both IL-17 and IL-10 in the milieu can be ascribed to multiple cell sources, including both T cells and macrophages. In fact, Th17 cells differentiated in the presence of high levels of TGFβ and/or low levels of IL-23 are able to secrete both cytokines (57); moreover, IL-10 inhibits T cell production of IFNγ, but does not suppress IL-17 production by Th17 cells (58), so favoring coexistence of IL-17; finally, IL-17 stimulates IL-10 production by macrophages themselves (56). The facilitating role of IL-17 on the clearance of ANs may constitute an important feedback loop controlling the effects of IL-17 on granulopoiesis and acute inflammation. Consistent with this view, the activation of liver X receptors by ANs was recently reported in mice to elicit efficient clearance of senescent neutrophils via MerTK and to suppress the IL-23/IL-17 cytokine cascade (33). In addition, we suggest that IL-17 could modulate innate immune responses by switching proinflammatory forms of neutrophil programmed cell death into regulatory ones. It is noteworthy, in fact, that recognition of late apoptotic blebs by antigen presenting cells stimulates T cell production of IL-17 (59); moreover, IL-17 is released by neutrophils themselves during NETosis (25). By eliciting macrophage phagocytosis of early ANs, IL-17 may eventually redirect the fate of dying neutrophils towards resolution of innate inflammation and tissue homeostasis.

Our findings may have therapeutic implications. Th17-mediated disease flares can promptly respond to glucocorticoid therapy, whereas Th1 and chronic Th2 inflammation may cause glucocorticoid resistance. Detection of high levels of IFNγ and IL-4 in inflamed tissues may suggest alternative anti-inflammatory (“steroid sparing”) treatments or the use of drugs that can reverse glucocorticoid resistance (e.g., MAPK inhibitors, vitamin D, theophylline, antioxidants) (38).

In the course of this study, we observed that different Th cytokine environments promote macrophage expression of different MerTK isoforms. Graham and colleagues recently found that Gas6 induces an intracellular 150-KDa MerTK glycoform (29). In accord with Gas6 upregulation by IL-4, we observed that M2a macrophages specifically express the 150-KDa MerTK isoform. This observation helps us to interpret our previous finding that IL-4 stimulates Gas6 production by M2a macrophages but does not upregulate MerTK on their membrane (10). Consistent with the higher levels of Gas6 produced by glucocorticoids in the presence of IL-17 compared to glucocorticoids alone, the 150-KDa MerTK isoform was also detectable in the presence of IL-17. The intracellular MerTK glycoform is not involved in membrane recognition of apoptotic cells, but it might play a role in gene modulation, as suggested by its capability to translocate to nucleus (29). Further investigation will be needed to better define its role.

The cytokines tested in the present study were used at standard doses, on the basis of previous similar in vitro studies (ranging from 10 to 100 ng/ml). For many of these cytokines, previous in vivo studies have determined their plasma levels, generally lower than the concentrations used herein (in the range of pg/ml). However, plasma levels do not reflect the local tissue levels reached in sites of inflammation. We chose concentrations of cytokines to reflect their peak bioactivity, in order to detect and compare their full effects.

Although macrophage autofluorescence might complicate flow cytometry analysis, in our hands we did not clearly observe autofluorescent cell populations. Accordingly, previous data reported that autofluorescence is low or negligible in monocytes-macrophages cultured in vitro for few days (60). Macrophage autofluorescence is instead a characteristic of resident tissues macrophages (e.g., murine bone marrow and peritoneal macrophages, human alveolar macrophages), and might be in part due to in vivo uptake of remnants and environmental particles (61).

In conclusion, different T-helper cytokine environments determine different responses of innate immunity to anti-inflammatory treatments. Our data highlight the unexpected role of IL-17 in orchestrating resolution of innate inflammation, by amplifying and protracting macrophage susceptibility to M2c differentiation and phagocytosis of ANs. By contrast, IFNγ and IL-4 limit the expansion of regulatory macrophages and might elicit autoimmunity owing to induction of apoptotic macrophages and uncontrolled accumulation of ANs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), grant 5U19AI082726 (Philadelphia Autoimmunity Center of Excellence), and by a bequest from Ms. B. Wicks.

Glossary

3 Abbreviations used in this paper

- MerTK

Mer tyrosine kinase

- ANs

apoptotic neutrophils

- Th

T helper

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

REFERENCES

- 1.Estaquier J, Ameisen JC. A role for T-helper type-1 and type-2 cytokines in the regulation of human monocyte apoptosis. Blood. 1997;90:1618–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt M, Lügering N, Pauels HG, Schulze-Osthoff K, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. IL-10 induces apoptosis in human monocytes involving the CD95 receptor/ligand pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:1769–1777. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1769::AID-IMMU1769>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt M, Lügering N, Lügering HG, Pauels HG, Schulze-Osthoff K, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Role of the CD95/CD95 ligand system in glucocorticoid-induced monocyte apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1344–1351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ottonello L, Bertolotto M, Montecucco F, Dapino P, Dallegri F. Dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of human monocytes exposed to immune complexes. Intervention of CD95- and XIAP-dependent pathways. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2005;18:403–415. doi: 10.1177/039463200501800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrchen J, Steinmüller L, Barczyk K, Tenbrock K, Nacken W, Eisenacher M, Nordhues U, Sorg C, Sunderkötter C, Roth J. Blood. 2007;109:1265–1274. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabat R, Grütz G, Warszawska K, Kirsch S, Witte E, Wolk K, Geginat J. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savill JS, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Walport MJ, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bratton DL, Henson PM. Neutrophil clearance: when the party is over, clean-up begins. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zizzo G, Hilliard BA, Monestier M, Cohen PL. Efficient Clearance of Early Apoptotic Cells by Human Macrophages Requires M2c Polarization and MerTK Induction. J. Immunol. 2012;189:3508–3520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McColl A, Bournazos S, Franz S, Perretti M, Morgan BP, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Glucocorticoids induce protein S-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2009;183:2167–2175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahuczky G, Kristóf E, Majai G, Fésüs L. Differentiation and glucocorticoid regulated apopto-phagocytic gene expression patterns in human macrophages. Role of Mertk in enhanced phagocytosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sierra-Filardi E, Vega MA, Sánchez-Mateos P, Corbí AL, Puig-Kröger A. Heme Oxygenase-1 expression in M-CSF-polarized M2 macrophages contributes to LPS-induced IL-10 release. Immunobiology. 2010;215:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alciato F, Sainaghi PP, Sola D, Castello L, Avanzi GC. TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 expression is inhibited by GAS6 in monocytes/macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;87:869–875. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0909610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denny MF, Chandaroy P, Killen PD, Caricchio R, Lewis EE, Richardson BC, Lee KD, Gavalchin J, Kaplan MJ. Accelerated macrophage apoptosis induces autoantibody formation and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2006;176:2095–2104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eken C, Martin PJ, Sadallah S, Treves S, Schaller M, Schifferli JA. Ectosomes released by polymorphonuclear neutrophils induce a MerTK-dependent anti-inflammatory pathway in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:39914–39921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn W, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell. Biol. 2007;176:231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen PL, Caricchio R, Abraham V, Camenisch TD, Jennette JC, Roubey RA, Earp HS, Matsushima G, Reap EA. Delayed apoptotic cell clearance and lupus-like autoimmunity in mice lacking the c-mer membrane tyrosine kinase. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:135–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muñoz LE, Janko C, Grossmayer GE, Frey B, Voll RE, Kern P, Kalden JR, Schett G, Fietkau R, Herrmann M, Gaipl US. Remnants of secondarily necrotic cells fuel inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1733–1742. doi: 10.1002/art.24535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rydell-Törmänen K, Uller L, Erjefält JS. Direct evidence of secondary necrosis of neutrophils during intense lung inflammation. Eur. Respir. J. 2006;28:268–274. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00126905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krysko O, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV, Bachert C. Impairment of phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and its role in chronic airway diseases. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1137–1146. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, Nguyen JX, Marques MB, Monestier M, Toy P, Werb Z, Looney MR. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2661–2671. doi: 10.1172/JCI61303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, Rubin CJ, Zhao W, Olsen SH, Klinker M, Shealy D, Denny MF, Plumas J, Chaperot L, Kretzler M, Bruce AT, Kaplan MJ. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2011;187:538–552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan MJ. Neutrophils in the pathogenesis and manifestations of SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011;7:691–699. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin AM, Rubin CJ, Khandpur R, Wang JY, Riblett M, Yalavarthi S, Villanueva EC, Shah P, Kaplan MJ, Bruce AT. Mast cells and neutrophils release IL-17 through extracellular trap formation in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 2011;187:490–500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren Y, Tang J, Mok MY, Chan AW, Wu A, Lau CS. Increased apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages and impaired macrophage phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2888–2897. doi: 10.1002/art.11237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh CH, Hilliard B, Li S, Merrill JT, Cohen PL. TAM receptor ligands in lupus: protein S but not Gas6 levels reflect disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010;12:R146. doi: 10.1186/ar3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambarus CA, Krausz S, van Eijk M, Hamann J, Radstake TR, Reedquist KA, Tak PP, Baeten DL. Systematic validation of specific phenotypic markers for in vitro polarized human macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods. 2011;375:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Migdall-Wilson J, Bates C, Schlegel J, Brandão L, Linger RM, DeRyckere D, Graham DK. Prolonged exposure to a Mer ligand in leukemia: Gas6 favors expression of a partial Mer glycoform and reveals a novel role for Mer in the nucleus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giles KM, Ross K, Rossi AG, Hotchin NA, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Glucocorticoid augmentation of macrophage capacity for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells is associated with reduced p130Cas expression, loss of paxillin/pyk2 phosphorylation, and high levels of active Rac. J. Immunol. 2001;167:976–986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stout RD, Jiang C, Matta B, Tietzel I, Watkins SK, Suttles J. Macrophages sequentially change their functional phenotype in response to changes in microenvironmental influences. J. Immunol. 2005;175:342–349. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heasman SJ, Giles KM, Rossi AG, Allen JE, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Interferon gamma suppresses glucocorticoid augmentation of macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:1752–1761. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong C, Kidani Y, A-Gonzalez N, Phung T, Ito A, Rong X, Ericson K, Mikkola H, Beaven SW, Miller LS, Shao WH, Cohen PL, Castrillo A, Tontonoz P, Bensinger SJ. Coordinate regulation of neutrophil homeostasis by liver X receptors in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:337–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI58393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anwar A, Keating AK, Joung D, Sather S, Kim GK, Sawczyn KK, Brandão L, Henson PM, Graham DK. Mer tyrosine kinase (MerTK) promotes macrophage survival following exposure to oxidative stress. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009;86:73–79. doi: 10.1189/JLB.0608334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan MJ, Lewis EE, Shelden EA, Somers E, Pavlic R, McCune WJ, Richardson BC. The apoptotic ligands TRAIL, TWEAK, and Fas ligand mediate monocyte death induced by autologous lupus T cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6020–6029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.6020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbarin V, Xing Z, Delos M, Lison D, Huaux F. Pulmonary overexpression of IL-10 augments lung fibrosis and Th2 responses induced by silica particles. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005;288:L841–848. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00329.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pechkovsky DV, Prasse A, Kollert F, Engel KM, Dentler J, Luttmann W, Friedrich K, Müller-Quernheim J, Zissel G. Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin. Immunol. 2010;137:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes PJ, Adcock M. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory diseases. Lancet. 2009;373:1905–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitman SC, Ravisankar P, Daugherty A. Interleukin-18 enhances atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E(−/−) mice through release of interferon-gamma. Circ. Res. 2002;90:E34–38. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.105292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meduri GU, Annane D, Chrousos GP, Marik PE, Sinclair SE. Activation and regulation of systemic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest. 2009;136:1631–1643. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrell RJ, Kelleher D. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Endocrinol. 2003;178:339–346. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng J, Younge BR, Olshen RA, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Th17 and Th1 T-cell responses in giant cell arteritis. Circulation. 2010;121:906–915. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.872903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leung DY, Spahn JD, Szefler SJ. Steroid-unresponsive asthma. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;23:387–398. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sumi Y, Hamid Q. Airway remodeling in asthma. Allergol. Int. 2007;56:341–348. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-07-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar RK, Yang M, Herbert C, Foster PS. Interferon-γ, Pulmonary Macrophages and Airway Responsiveness in Asthma. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11:292–297. doi: 10.2174/187152812800958951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sergejeva S, Ivanov S, Lötvall J, Lindén A. Interleukin-17 as a recruitment and survival factor for airway macrophages in allergic airway inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2005;33:248–253. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0213OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curtis MM, Way SS. Interleukin-17 in host defence against bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal pathogens. Immunology. 2009;126:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong CK, Lit LC, Tam LS, Li EK, Wong PT, Lam CW. Hyperproduction of IL-23 and IL-17 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: implications for Th17-mediated inflammation in auto-immunity. Clin. Immunol. 2008;127:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zizzo G, De Santis M, Bosello SL, Fedele AL, Peluso G, Gremese E, Tolusso B, Ferraccioli G. Synovial fluid-derived T helper 17 cells correlate with inflammatory activity in arthritis, irrespectively of diagnosis. Clin. Immunol. 2011;138:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarzenberger P, La Russa V, Miller A, Ye P, Huang W, Zieske A, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Stoltz D, Mynatt RL, Spriggs M, Kolls JK. IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis in mice: use of an alternate, novel gene therapy-derived method for in vivo evaluation of cytokines. J. Immunol. 1998;161:6383–6389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Lindén A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dragon S, Saffar AS, Shan L, Gounni AS. IL-17 attenuates the anti-apoptotic effects of GM-CSF in human neutrophils. Mol. Immunol. 2008;45:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang ZG, He QY, Liu XM, Tang XY, Chen LZ. [Effect of Interleukin-17 on neutrophil apoptosis] Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006;38:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silverpil E, Glader P, Hansson M, Lindén A. Impact of interleukin-17 on macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and particles. Inflammation. 2011;34:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chanteux H, Guisset AC, Pilette C, Sibille Y. LPS induces IL-10 production by human alveolar macrophages via MAPKinases- and Sp1-dependent mechanisms. Respir. Res. 2007;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jovanovic DV, Di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Jolicoeur FC, He Y, Zhang M, Mineau F, Pelletier JP. IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-beta and TNF-alpha, by human macrophages. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3513–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Cua DJ. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naundorf S, Schröder M, Höflich C, Suman N, Volk HD, Grütz G. IL-10 interferes directly with TCR-induced IFN-gamma but not IL-17 production in memory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1066–1077. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fransen JH, Hilbrands LB, Ruben J, Stoffels M, Adema GJ, van der Vlag J, Berden JH. Mouse dendritic cells matured by ingestion of apoptotic blebs induce T cells to produce interleukin-17. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2304–2313. doi: 10.1002/art.24719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Njoroge JM, Mitchell LB, Centola M, Kastner D, Raffeld M, Miller JL. Characterization of viable autofluorescent macrophages among cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cytometry. 2001;44:38–44. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20010501)44:1<38::aid-cyto1080>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiter C. Fluorescence test to identify deep smokers. Forensic Sci Int. 1986;31:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(86)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.