Abstract

Objectives

The present study investigated whether anxiety and depressive symptomatology moderates the relationship between age and quality of life.

Methods

The study was a community-based survey using mailed questionnaires conducted within the Department of Psychology at Washington University in St. Louis. The community-based sample consisted of 443 adults ages 30 to 98 years recruited from university maintained volunteer registries. Quality of life was assessed using the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF assessment; Depression was assessed using 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale and anxiety was assessed using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale, a measure of social anxiety.

Results

Depression and anxiety were negatively associated with qualify of life in the Psychological and Social domains (all ps < .001), but age was not (Psychological, p = .07; Social, p = .98). In addition to depression and anxiety, age was also associated with quality of life in the other two domains, negatively for the Physical domain and positively for the Environmental domain. These main effects were qualified by significant three-way interactions in both domains.

Conclusions

Although both anxiety and depression negatively affect Psychological and Social quality of life, age does not. Environmental quality of life increased with age, while Physical quality of life decreased. The deleterious relationship between anxiety and depressive symptomatology and Physical and Environmental quality of life was moderated by age. Older adults with high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms reported better Environmental and less severe decrements in Physical quality of life compared with middle-aged adults with similar symptomatology.

Keywords: Age, Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life

Early work concluded that a happy individual was a “young, healthy, well-educated, extroverted, optimistic, worry-free, religious, married person with high self-esteem, job morale, modest aspirations, of either sex and a wide range of intelligence” (Wilson, 1967; p. 294). Of particular interest to gerontologists is the assertion that youth is a necessary component of happiness. In opposition of this assertion, subsequent studies have shown either no age effect or an increase in life satisfaction in later years (Andrews & Withey, 1976; Herzog & Rodgers, 1981; Stock et al., 1983). In a large-scale cross-sectional survey of an adult sample Diener and Suh (1998) reported an upward trend in life satisfaction from 20 to 80 years of age, with stability of negative affect across this age range; positive affect did, however, decline as age increased. Although there is some evidence for decreases in emotional intensity with increasing age (Diener et al., 1998), Ryff (1991) found that older adults reported a closer match to their own notion of their “ideal self” compared with younger adults. The literature as a whole shows strong support contradicting the assumption that youth is a requirement for happiness. In fact, the literature leans in the opposite direction, illuminating people’s apparent successful ability to adapt to both physical and environmental changes as they age (Diener et al., 1999).

As individuals age, however, they are more likely to experience an increase in physical limitations and medical problems; these limitations have been shown to predict increases in depressive symptoms over time (Gayman et al, 2008). Recent findings have called attention to subsyndromal depression or anxiety symptoms as predictors of poorer ability to care for one’s self at follow-up (Grabovich et al., 2010). Relatedly, anxiety and depression are associated with poorer health-related quality of life (Stein & Barrett-Connor, 2002). Lawton, Kleban, and Dean (1993) found that younger adults endorsed depression as well as anxiety and shyness more frequently than older adults. Findings from these two lines of research suggest the question: Do older adults with anxiety and depressive symptomatology report poorer quality of life similarly to middle-aged adults? Thus in this study we examined the relationship between age, anxiety and depressive symptomatology, and domains of quality of life. We hypothesized that, although quality of life in several domains is better with increased age, this relationship is moderated by the presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms; reports of better quality of life in later life are tempered by anxiety and depressive symptomatology.

Methods

Participants

The cross-sectional community-based sample included 443 (70% women) adults aged 30 to 98 years (M = 65.26, SD = 16.45) recruited through community volunteer registries maintained by the Psychology Department and the Medical School at Washington University in St. Louis; members of the Psychology Department supplemented the sample. The sample was well educated (M = 15.48 years, SD = 3.23) and primarily Caucasian (90%).

Measures

Depression

The 15-tem Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986; Brown et al., 2007) represents a short version of the original 30-item GDS (Yesavage et al., 1983) that was the first depression screening measure designed specifically for a geriatric population by eliminating somatic items that are more common in nondepressed older adults. The 15-item GDS uses a dichotomous-response method (Yes/No) for each item.

Anxiety

The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) is a 20-item measure of social interaction anxiety using a 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) Likert response scale. The items describe anxiety-related reactions to a variety of social interaction situations. The 17 straightforwardly worded items were used in this study as they demonstrated better internal consistency (α = .94) compared with the full 20-item measure, which included three reverse-scored items (α = .86; Rodebaugh et al., under review).

Quality of life

Physical, Psychological, Social, and Environmental domains of quality of life were measured using the 26-item World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF assessment tool (WHOQOL-BREF; The WHOQOL Group, 1998). The seven-item Physical domain assesses people’s satisfaction with physical health, medical treatment, mobility, the ability to perform daily tasks, and sleep. The five-item Psychological domain assesses people’s satisfaction with their lives, their ability to concentrate, and their satisfaction with themselves and their body type. The three-item Social domain assesses people’s satisfaction with their relationships, sex life, and support from their friends. The eight-item Environmental domain assesses people’s satisfaction with the safety and health of their environment, the availability of information, health services, and leisure activities and their financial standing within the environment, and the overall conditions of the environment. The measure uses a 1 to 5 Likert response scale with higher scores indicating better quality of life. In a multicenter international study of 11,830 adults ranging in age from 12 to 97 years, the Cronbach α for Physical domain (.82), Psychological domain (.81), and Environmental domain (.80) were acceptable, although it was marginal for the Social domain (.68; The WHOQOL Group, 2004).

Procedure

Participants were contacted by telephone, e-mail, or mail and provided a description of the study. Questionnaires and self-addressed stamped return envelopes were mailed to those who gave verbal consent. Participants from the Psychology Department could take the questionnaires from the departmental mailroom and return it to the investigator’s mailbox after completion. Participants were instructed not to include their names on any of the questionnaires thereby assuring their anonymity; they were not reimbursed for participation. The Washington University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Statistical analysis

Four hierarchical linear regression models were used to examine the relationship between domains of quality of life (dependent variables) and age, depression, and anxiety variables as well as their interactions. Because education was associated with Physical quality of life (r = .19, p < .001) it was included as a control variable in the first step for all analyses. Gender was not associated with any of the quality of life domains.

Results

Demographic, mental health, and quality of life variables were separated into three age groups for ease of display (30–59, 60–79, 80–98 years) and are listed in Table 1. The main effects of age, depression, and anxiety explained 61% of the variance for Psychological quality of life, F(3, 427) = 229.02, p < .001, and 27% of the variance for Social quality of life, F(3, 427) = 53.25, p < .001. Both depression and anxiety were negatively associated with the Psychological and Social quality of life, (ps < .001), but age did not make a significant contribution (Psychological, p = .07; Social, p = .98). Neither the three-way interaction nor any of the two-way interactions were significant for these two domains (all ps ≥ .20).

Table 1.

Characteristics of community-dwelling sample by age group.

| Age groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30–59 | 60–79 | 80–98 | |

| Variables | (n = 154) | (n = 184) | (n = 105) |

| Age (years) | 46.11 (9.48) | 70.57 (5.76) | 84.04 (3.59) |

| Gender (women/men) | 115 / 39 | 129 / 55 | 67 / 38 |

| Education (years) | 16.30 (3.10) | 15.54 (3.22) | 14.41 (3.02) |

| Social Interaction Anxiety Scale | 15.51 (12.60) | 11.38 (9.38) | 11.14 (8.98) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 3.03 (3.52) | 1.70 (2.42) | 2.12 (2.57) |

| Physical Well-being | 27.63 (5.93) | 27.81 (4.50) | 26.63 (4.76) |

| Psychological well-being | 21.71 (4.74) | 23.46 (3.33) | 23.35 (3.24) |

| Social Well-being | 10.56 (2.70) | 11.17 (1.98) | 11.52 (1.77) |

| Environmental Well-being | 30.19 (5.72) | 33.35 (4.07) | 33.43 (4.42) |

Note. Except for gender, entries are means with standard deviations shown in parentheses. Physical, Psychological, Social, and Environmental domain scores computed by adding component scores from the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF assessment tool; Depression is the total score derived from the sum of each of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; Anxiety is the total score derived from the sum of each of the 17 straight-forwardly worded items from the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale.

The main effects of age, depression, and anxiety explained 35% of the variance in Physical quality of life, F(3, 427) = 80.34 p < .001, and 32% of the variance in Environmental quality of life, F(3, 427) = 66.96, p < .001. In addition to significant effects of depression and anxiety, age also made a unique contribution to both Physical and Environmental quality of life; the Physical domain worsened with increased age (p < .001); the Environmental domain improved with increased age (p < .001). These main effects, however, were qualified by an Age × Anxiety × Depression interaction for both the Physical, F(1, 423) = 4.43, p < .05, and Environmental domain models, F(1, 423) = 4.68, p < .05.

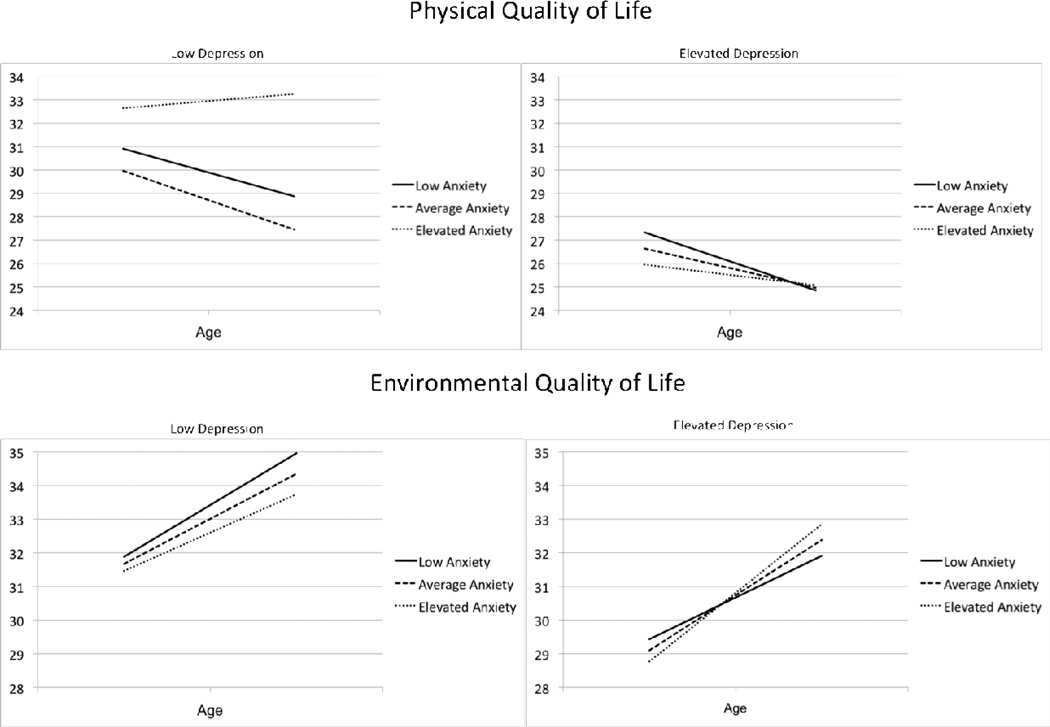

The top portion of Figure 1 displays the simple regression lines depicting the three-way interaction for the Physical quality of life domain with a mean education level of 15.48 years. Depression was set at either a low (GDS = 1) or elevated value (GDS = 4). Anxiety, assessed using a measure of social anxiety, was set at low (SIAS = 3), average (SIAS = 13), and elevated (SIAS = 23) values. For low values of depression (upper left portion of Figure 1), Physical quality of life decreased with age if anxiety was low or average, but surprisingly increased albeit slightly with age for those with elevated anxiety. If depression was elevated (upper right portion of Figure 1), Physical quality of life decreased with age at all values of anxiety, but the negative effect of anxiety on Physical quality of life apparent in younger people disappeared with age.

Figure 1.

Regression lines for the Age × Depression × Anxiety interaction for Physical and Environmental quality of life domains.

Note. Regression lines were derived based on the unstandardized regression coefficients from Step 4 of the two regression analyses: The regression equation from Step 4 of the Physical quality of life model: Yphys = 32.39 + .104 (educ) − .044 (age) − .933 (dep) − .009 (anx) − .002 (age × anx) − .006 (age × dep) − .035 (anx × dep) + .001 (age × anx × dep). The regression equation from Step 4 of the Environmental quality of life model: Yenviron = 26.68 + .165 (educ) + .088 (age) − .485 (dep) + .063 (anx) − .002 (age × anx) − .008 (age × dep) − .044 (anx × dep) + .001 (age × anx × dep). Both models assumed a mean level of education (15.48 years from the total sample). Anxiety scores were divided into Low (SIAS = 3), Average (SIAS = 13), and Elevated (SIAS = 23). Depression was divided into Low (GDS = 1), and Elevated (GDS = 4). SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; GDS = 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale.

The bottom portion of Figure 1 displays the regression lines depicting the Age × Depression × Anxiety interaction for Environmental quality of life, again with a mean education of 15.48 years. With low depression (bottom left portion of Figure 1), Environmental quality of life increased with age at each level of anxiety, and higher anxiety was associated with poorer Environmental quality of life. With elevated depression (bottom right portion of Figure 1), although Environmental quality of life increased with age at all three levels of anxiety, older adults with elevated levels of anxiety report greater Environmental quality of life than older adults with average or low levels of anxiety (i.e., a reversal of the main effect of anxiety seen when depression was low).

Discussion

Despite assertions that youth was a necessary feature of happiness, research on quality of life and life satisfaction has shown that perhaps the opposite is true. With increasing age comes a greater sense of self as older adults envision themselves as closer to their “ideal” than do younger adults (Ryff, 1991). Although these findings are for nonclinical populations, anxiety and depression have been shown to be associated with poorer health-related quality of life (Stein & Barrett-Connor, 2002). This study was primarily interested in addressing both lines of research to identify whether older adults with anxiety and depressive symptomatology reported poorer quality of life, similarly to the reports of middle-aged adults. We hypothesized that the presence of increased anxiety or depressive symptoms would mute any protective effect of age on quality of life. The results, however, were contrary to the hypothesis and varied by quality of life domain.

We found that increased age did not mean decreased quality of life, and this was true for Psychological, Social, and Environmental quality of life domains, although not for the Physical domain. Greater depression and anxiety symptomatology was associated with poorer Social and Psychological quality of life; age had no impact on these two domains. Psychological quality of life as a construct is closely related to depression and anxiety, and thus it was not surprising that depression and anxiety symptomatology explained most of the variance. We were however surprised by the lack of an age association with Social quality of life. Because of the high functioning, well-educated, nature of the community sample and the positive effects derived from social engagement on older adults (Carlson et al., 2009), we believed that Social quality of life would increase with age. It could be that any hypothesized increased satisfaction with social relationships is countered by increased losses that occur in later life. Regardless, neither Social nor Psychological quality of life decreased with age.

Anxiety and depressive symptomatology did moderate the relationship between age and Physical and Environmental quality of life, but the moderation effect differed from the one hypothesized. Environmental quality of life increased with age. If depression was minimal, Environmental quality of life increased with age at each level of anxiety, with higher levels of anxiety associated with poorer Environmental quality of life. If depression was elevated, however, although Environmental quality of life increased with age, older adults with elevated anxiety reported better Environmental quality of life than older adults with average or low anxiety levels, a finding contrary to the main effects observed for low levels of depression. Despite the presence of subthreshold symptomatology, older adults in this sample reported greater satisfaction with the infrastructure that surrounds them. This finding may represent an inherent pride resulting from years of working to create and select surroundings that maximize their quality of life. Whereas the younger adults have perhaps been unable to achieve such Environmental satisfaction, the older adults in this study, even in the presence of depression or anxiety symptoms, remain satisfied with the surrounding infrastructure. This finding perhaps alludes to an increased environmental competence or mastery (Ryff, 1989a; Ryff, 1989b) that comes with age, or it may be a proxy indicator for the effect of the potentially higher socioeconomic nature of this sample (Grundy & Bowling, 1999); with increasing means comes an improved ability to select an environment that maximizes one’s quality of life.

Whereas Environmental quality of life increased with age, Physical quality of life decreased if depression was minimal and at low or average levels of anxiety. Interestingly, however, Physical quality of life increased slightly with age for those with elevated anxiety levels. If depression was elevated, the negative effect of anxiety on Physical quality of life apparent in younger adults was diminished in older adults. Although Physical quality of life decreased with age, age appeared to temper the effect of greater anxiety and depressive symptomatology on Physical quality of life. It is difficult to formulate a cogent explanation for this finding. Although it makes sense that we found poorer Physical quality of life with increasing age given that medical comorbidities and increased functional deficits increase with age, it is difficult to surmise why, with elevated anxiety and/or depression, this decrease in Physical quality of life is tempered. Perhaps with increased age, greater exposure to life experiences increases ones ability to adapt to physical or environmental changes and greater anxiety or depressive symptomatology (Baltes & Carstensen, 2003; Jopp & Smith, 2006; Lawton, 1991). It could be, however, that this moderation effect is an anomaly, a finding that will be difficult to replicate. In any event, a cogent explanation is not apparent.

The relationships between age and the Psychological, Social, and Environmental quality of life domains in this study mirror findings from the Midlife Development in the U.S. (MIDUS) national survey showing stability or increments in components of quality of life with age (Ryff et al., 2004), although the focus of this present study is subjective quality of life/life satisfaction which differs from Ryff’s psychological well-being construct (Ryff, 1989a; Ryff, 1989b). This finding was particularly important given the robust age-range (30–98 years) of the sample including a substantial sample of adults in the so-called “old old” demographic, one of the fastest growing segments of the population (United States Census Report, 2002). The deleterious effect of anxiety and depressive symptomatology on quality of life is consistent with recent findings showing greater depression and/or anxiety symptoms associated with worse outcomes (Grabovich et al., 2010; Stein & Barrett-Connor, 2002) as well as poorer self-rated successful aging, self-efficacy and optimism, and worse physical and emotional functioning (Vahia et al., 2010). This study addressed both lines of research by showing that age was unrelated to Social and Psychological quality of life and appeared to temper the deleterious effect of elevated anxiety and depressive symptomatology on Physical and Environmental quality of life, although again the former finding is difficult to explain.

There are, of course, limitations to the study design that caution generalizability. The study is cross-sectional and can only hypothesize about causal mechanisms. Important variables that could alter these conclusions such as physical health status, socioeconomic status, history of depression or anxiety disorders, functional impairment, and cognitive status were not assessed. Also, this was a highly educated and primarily white, female community-sample; thus the associations found in this study might not generalize to more diverse, less educated, institutionalized, or clinical samples. It should also be noted that comparing age groups in a cross-sectional manner leaves this study susceptible to a cohort effect. Despite many of these participants recruited from a hospital registry in an attempt to construct a sample somewhat representative of the community at large, and the use of mailed questionnaires rather than requiring a visit to the Department of Psychology, the volunteers in this sample were primarily high functioning, well educated, and female; as such, they may represent a more physically and psychologically healthy cohort of older individuals than is representative in the population, an issue that has been shown elsewhere (Morrow-Howell, 2010). If so, caution should be taken when interpreting these relationships between age, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and domains of quality of life. Finally, anxiety was assessed using a measure of social anxiety, which is not often studied in older adults despite older adults having higher 12-month prevalence rates of social anxiety disorder (3.5%) compared with any other anxiety disorder except specific phobias (Byers et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, these findings add to the growing body of research showing that youth is not an essential component to better quality of life. Although both anxiety and depression negatively affect Psychological and Social quality of life, age does not. The negative effect of elevated anxiety and depressive symptomatology on Environmental quality of life appeared to be tempered by older age. Older adults with greater anxiety and depressive symptomatology report better Environmental quality of life compared with middle-aged adults with similar symptom profiles. Physical health decreased with age across each level of anxiety and depressive symptomatology with the lone exception being those participants with Low depression and elevated anxiety. Insight into this age effect, whether it is due to greater adaptation or exposure to individual life experiences, may aid clinicians in improving the quality of life for adults with clinically significant impairment.

KEY POINTS.

Psychological and Social quality of life do not differ with age; Environmental quality of life increases with age; Physical quality of life decreases with age; The deleterious effect of anxiety and depressive symptomatology on Environmental quality of life is tempered by age.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging (grant number 5 T32 AG0030) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number T32 MH20004). The author wishes to thank Brian Carpenter and Thomas Rodebaugh for their help on this project, and Manisha Chandar for her help in recruitment. A special thanks to Martha Storandt, whose input and mentorship were invaluable throughout the entire research process.

Dr. Roose has received research support from Forest Laboratories and serves as a consultant for Medtronics. These sponsors’ had no role in this current manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Brown has nothing to disclose.

References

- Andrews FM, Withey SB. Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes MM, Carstensen LL. The process of successful aging: Selection, optimization and compensation. In: Staudinger UM, editor. Understanding human development: Dialogues with lifespan psychology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Woods CM, Storandt M. Model Stability of the 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale across Cognitive Impairment and Severe Depression. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:372–379. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, et al. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:489–496. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MC, Erickson KI, Kramer AF, et al. Evidence for Neurocognitive Plasticity in At-Risk Older Adults: The Experience Corps Program. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1275–1282. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Sandvik E, Larsen RJ. Age and sex effects for emotional intensity. Dev Psychol. 1998;21:542–546. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh E. Age and subjective well-being: An international analysis. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 1998;17:304–324. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, et al. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Gayman MD, Turner RJ, Cui M. Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: Exploring the nature of the association. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:S219–S228. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabovich A, Lu N, Tang W, et al. Outcomes of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:227–235. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cb87d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E, Bowling A. Enhancing the quality of extended life years. Identification of the oldest old with a very good and very poor quality of life. Aging Ment Health. 1999;3:199–122. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Rodgers WL. Age and satisfaction: Data from several large surveys. Res Aging. 1981;3:142–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jopp D, Smith J. Resources and life-management strategies as determinants of subjective well-being in very old age: The protective effect of selection, optimization, and compensation. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:253–265. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. A multidimensional view of quality of life in frail elders. In: Birren JE, Lubben JE, Rowe JC, Deutchman DE, editors. The concept and measurement of quality of life in the frail elderly. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1991. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Dean J. Affect and age: Cross-sectional comparisons of structure and prevalence. Psychol Aging. 1993;8:165–175. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N. Volunteering in Later Life: Research Frontiers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B:461–469. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Heimberg RG, Brown PJ, et al. More Reasons to be Straightforward: Findings and Norms for Two Scales Relevant to Social Anxiety. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.002. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful aging. Int J Behav Dev. 1989a;12:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989b;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Possible selves in adulthood and old age: A tale of shifting horizons. Psychol Aging. 1991;6:286–295. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM, Hughes DL. Psychological well-being in MIDUS: Profiles of ethnic/racial diversity and life-course uniformity. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 398–424. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Barrett-Connor E. Quality of life in older adults receiving medications for anxiety, depression, or insomnia. Findings from a community-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:568–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock WA, Okun MA, Haring MJ, et al. Age and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. In: Light RJ, editor. Evaluation studies: Review annual. Vol. 8. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1983. pp. 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Report. US Bureau of the Census. Washington, D.C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vahia IV, Meeks TW, Thompson WK, et al. Subthreshold depression and successful aging in older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:212–220. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b7f10e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. Correlates of avowed happiness. Psychol Bull. 1967;67:294–306. doi: 10.1037/h0024431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose T, et al. Development and validation of the geriatric depression screen scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]