Abstract

Background

Prior research has documented a counterintuitive positive association between physical activity and indices of alcohol consumption frequency and heaviness.

Objectives

To investigate whether this relation extends to alcohol use disorder and clarify whether this association is non-linear.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, correlational population-based study of US adults (N = 34,653). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule was used to classify past-year DSM-IV alcohol use disorder and self-reported federal government-recommended weekly physical activity cutoffs.

Results

After statistically controlling for confounds, alcohol abuse but not dependence was associated with greater prevalence of physical activity. Number of alcohol use disorder symptoms exhibited a curvilinear relationship with meeting physical activity requirements, such that the positive association degraded with high symptom counts.

Conclusion

There is a positive association between physical activity and less severe forms of alcohol use disorder in US adults. More severe forms of alcohol use disorder are not associated with physical activity.

Keywords: physical activity, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, health promotion, population-based survey, NESARC

INTRODUCTION

While physical activity is typically considered as a protective factor against health-damaging behaviors (1), evidence indicates a positive relationship between alcohol use and physical activity the general population (2), though results are not always consistent (1,3–5). However, no study has examined whether that relationship extends to alcohol use disorders. Common personality, biological, and social mechanisms appear to explain the link between physical activity and alcohol use. These mechanisms best explain why less severe forms of alcohol use disorder will be positively associated with physical activity. Nevertheless, extreme forms of alcohol abuse may be so overwhelming that physical activity becomes impossible. One study that was very heterogeneous in terms of demographics and alcohol use disorders (6) found an inverted U-shaped relation for drinking, peaking physical activity levels were associated with moderate drinking, and declined with heavy drinkers.

There are several potential mechanisms that may underlie positive associations between alcohol use and physical activity. Personality traits such as sensation seeking play a role. People high in sensation seeking may be more likely to engage in both high levels of physical activity and drinking for stimulation. In addition, there is evidence in preclinical models that the mesocorticolimbic neural circuit, a brain pathway associated with reward, is activated by both alcohol and exercise and could cause the two behaviors to couple (7). Thus, individuals with hyperresponsive mesolimbic circuitry may find both alcohol and physical activity reinforcing and habitually engage in both behaviors. Furthermore, socializing can be part of organized sport and often involves alcohol (e.g. going out to drinks after a softball game). Lastly, drinkers might attempt to shed calories from alcohol by engaging in more exercise.

Two population-based studies found a relation between physical activity and indicators of alcohol use frequency and consumption levels. French et al. (2) found that alcohol consumption was positively related to physical activity; though the possibility of a non-linear relationship between the two characteristics was not explored. Another study (6) found an inverted U-shaped curve, peaking for physical activity levels at moderate drinking, and declining with heavy drinkers.

Although there seems to be a relation between physical activity and alcohol use behavior in population-based samples (2,6), it is unclear whether this relation extends to alcohol use pathology. This is an important gap in the literature, given that alcohol use disorders are associated with morbidity and mortality and may result in impairment that could interfere with ability to exercise (8). Variability in alcohol use disorders can be represented in several ways. According to the DSM-IV, the diagnosis of alcohol abuse is a less severe form of alcohol use pathology than alcohol dependence. The DSM-V may eliminate this distinction by combining abuse and dependence symptoms into one alcohol-related disorder diagnosis with a set of criteria to note the severity and length (9). Thus, another means of representing variability in alcohol use disorder pathology is to explore symptom counts.

In addition, the linearity of the relation between alcohol use and physical activity are unclear. Several prior studies have shown a linear relation positive between alcohol use frequency and physical activity (10,11). However, Musselman and Rutledge and others used college samples with presumably little variability at the severe end of the alcohol use pathology continuum, thus a linear increase in drinking behavior in theses samples did not necessarily imply extreme pathology arising from alcohol. We postulate that because of the putatively common personality, biological, and social mechanisms linking physical activity and alcohol use described above, less severe forms of alcohol use disorder will be positively associated with physical activity. Yet, more severe forms of alcohol abuse may be so devastating such that physical activity becomes difficult. Indeed, in a population-based sample that had a high degree of heterogeneity with regard to demographics and alcohol use disorders (5), an inverted U-shaped relation for drinking was found, peaking for physical activity levels at moderate drinking, and declining with heavy drinkers.

The present cross-sectional study examined a putative non-linear association between past-year alcohol use pathology and physical activity in a population-based sample of US adults using two methods. The first analysis, based on the DSM-IV alcohol use disorder, with the modification that participants need not have abuse to qualify for dependence and may have dependence without abuse, given prior results suggesting that classifying these two disorders separately from one another (rather than stochastically and requiring abuse criteria to be met prior to considering dependence) sheds light on clinically important variability (12). Thus, we examine abuse (yes/no) and dependence (yes/no) as separate overlapping variables, given prior work indicating that diagnosing abuse in dependent individuals may account for clinically important heterogeneity (12). Because alcohol abuse is a less severe form of alcohol use disorder, we hypothesized that it would be positively related to meeting physical activity requirements, while, dependence, which may be a more severe and debilitating disorder, would not be associated with physical activity. The second analysis is based on number of alcohol use disorder symptoms. Here, we hypothesize that total number of symptoms will exhibit a quadratic inverted “U” relationship with meeting physical activity requirements, such that rates of physical activity with increase from low to moderate symptom count levels and decline from moderate to high symptom count levels. Finally, given the possibility that the relation between alcohol use and physical activity may be linear only among younger groups or among men (13), whether age and gender moderated associations between these two characteristics.

METHOD

Sample and Procedure

Participants were respondents in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; Wave 2, 2004–2005). The first wave was conducted in 2001–2002 and the second wave from 2004 to 2005. Details of the sampling, purpose, demographic profile, and weighting are described in greater detail elsewhere (14). To be eligible, participants had to be civilian, non-institutionalized individuals aged 18 and above. Respondents constituted a representative sample of the adult population of the United States.

The sampling frame of the NESARC was the US Bureau of Census Supplementary Survey and the Census 2000. In each household, one adult was selected, and face-to-face interviews were conducted in homes following informed consent. The response rate for Wave 1 was 81.0% and the response rate among those eligible for Wave 2 was 86.7% (N = 34,653). Among the 43,093 Wave 1 respondents, 39,959 people were eligible for a Wave 2 interview. Those classified as ineligible for a Wave 2 interview were institutionalized, mentally/physically impaired, or on active duty armed forces (n = 1731), or deceased, permanently moved or deported (n = 1403). The current analyses utilized the Wave 2 because physical activity was measured only at Wave 2. Analytic weights were applied to account for oversampling and adjusted to be representative of the 2000 US Census results by age, ethnicity, and gender (14).

Measures

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule IV (AUDADIS-IV) (15) was used to collect information on demographics, physical activity, substance use, DSM-IV criteria for mental disorders, and other characteristics. The reliability of abuse and dependence and other mental disorders diagnosed with the AUDADIS-IV is adequate (15).

Alcohol Use Disorder

The alcohol module of the AUDADIS-IV contains detailed questions on the frequency, quantity, and patterning of alcohol use as well as individual symptom criteria to diagnose past-year DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse.

Physical Activity

Participants were asked to report levels of moderate and vigorous physical activity over the past 12 months. Moderate physical activity was defined as “activities that caused only LIGHT sweating or SLIGHT to MODERATE increases in your breathing or heart rate,” and vigorous physical activity was defined as “activities that caused you to sweat HEAVILY or caused LARGE increases in your breathing or heart rate.” Participants were asked about the frequency and average duration of a typical period of activity. The US federal government currently recommends that adults should engage in at least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity, 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (16). As in previous work (17), our indicator was whether or not individuals met this weekly recommendation, on an average, over the past year. Adequate reliability and validity of self-report measures of physical activity has been documented (18,19).

Covariates

Demographics (gender, age, marital status, and education) and DSM-IV-defined non-alcohol substance use disorders, mood, and anxiety disorders over lifetime and past-year were incorporated as covariates (20). Age was measured as a continuous variable. One variable assessed lifetime non-alcohol mental disorder status (yes or no). Also included as a covariate, participants were asked “During the last 12 months, did you have a serious PERMANENT physical disability?” (1 = yes, 0 = no). It is important to adjust for other forms of substance and psychiatric and substance use pathology as these variables tend to associate with both alcohol use and physical activity (21) and therefore may confound associations.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models were conducted to examine whether diagnostic category (abuse and dependence) was associated with meeting (vs. not meeting) weekly physical activity recommendations in the past year adjusting for covariates. Abuse (yes/no) and dependence (yes/no) were separate simultaneous predictors. Next, logistic regression analysis was used in the same fashion with symptom count and symptom count squared (to test for a curvilinear effect) as the dependent variables adjusting for covariates. Based on previous findings (13), exploratory analyses of moderation by age and gender were also examined in diagnostic category models and symptom count (both linear and curvilinear) models.

Percentage rates are based on weighted estimates. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated using SAS software’s SURVEYLOGISTIC (SAS (2008), SAS/STAT® 9.2 User’s Guide) procedure to account for the complex sampling design of the NESARC. It computed the variances of the odds ratios using a Taylor expansion approximation. Because this is the first study of alcohol use disorder symptoms and physical activity and we did not want to overlook any potential findings, tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < .05 without alpha correction.

RESULTS

Demographic, Alcohol Use, and Physical Activity Characteristics by Alcohol Use Disorder

Table 1 reports physical activity, demographic, and alcohol use characteristics by each alcohol use diagnostic group.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics by alcohol use disorder (weighted).

| Abuse |

Dependence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Contrast (p) | Yes | No | Contrast (p) | |

| N | 1433 | 33220 | 2607 | 32046 | ||

| Sex (% male) | 73.04 | 45.73 | <.0001 | 68.59 | 46.96 | <.0001 |

| Age (M, SE) | 48.98, 0.11 | 38.73, 0.31 | <.0001 | 48.67 | 36.64 | <.0001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| White | 77.74 | 70.32 | 67.51 | 71.07 | ||

| Black | 8.55 | 11.27 | 12.58 | 10.98 | ||

| American Indian | 2.73 | 2.14 | 3.11 | 2.14 | ||

| Asian | 1.82 | 4.49 | 2.74 | 4.34 | ||

| Hispanic | 9.16 | 11.78 | <.0001 | 14.06 | 11.47 | <.05 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or living as married | 50.85 | 64.91 | 42.83 | 64.75 | ||

| Widowed | 1.25 | 7.73 | 1.83 | 7.46 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 15.70 | 11.30 | 16.80 | 11.42 | ||

| Never married | 32.20 | 16.06 | <.0001 | 38.54 | 16.37 | <.0001 |

| Education (%) | ||||||

| Did not complete high school | 9.32 | 14.43 | 15.68 | 13.94 | ||

| High school or GED | 27.65 | 27.47 | 24.42 | 27.53 | ||

| Some college or more | 63.09 | 58.10 | <.0001 | 59.9 | 58.53 | .31 |

| Meet physical activity recommendation (%) | 55.84 | 44.13 | <.0001 | 54.42 | 44.64 | <.001 |

| Number of drinks consumed on days when drank in last year (N, SE) |

4.77, 0.10 | 2.19, 0.02 | <.0001 | 5.57, 0.15 | 2.28, 0.18 | <.0001 |

| Number of days consumed alcohol in the last year (N, SE) |

153.87, 2.65 | 76.59, 0.87 | <.0001 | 173.09, 3.73 | 79.78, 0.85 | <.0001 |

Alcohol abuse and Dependence Diagnoses and Physical Activity

In a model that included abuse (no abuse vs. abuse) and dependence (no dependence vs. dependence) as simultaneous predictors of physical activity, abuse was significantly associated with physical activity adjusting for covariates, OR (95% CI) = 1.23(1.10–1.37), p < .0001, whereas dependence did not have a significant effect (p = .52). Results for covariates were as follows: disability, OR (95% CI) = .84 (.77–.92), p < .0001; non-alcohol mental disorder status, OR (95% CI) .83 (.75–.91), p < .0001; marital status, OR (95% CI) = 1.20 (1.14–1.26), p < .0001; age, OR (95% CI) = 1.01 (1.01–1.02), p < .0001; and male sex, OR (95% CI) = 1.45 (1.37–1.53), p < .0001. Interactions between alcohol use disorder (abuse and dependence) and both age and gender in predicting PA were non-significant.

Alcohol Use Disorder Symptom Count and Physical Activity

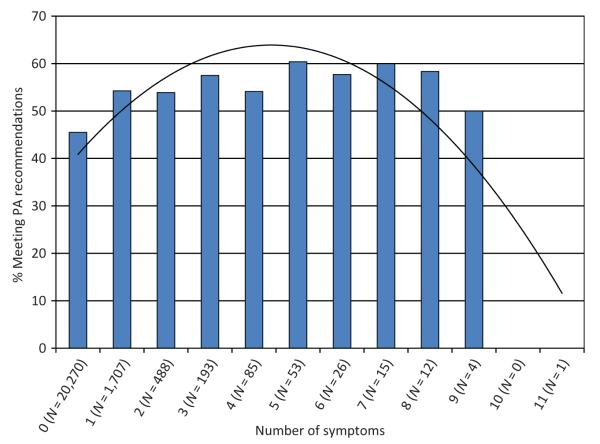

Logistic regression models included the quadratic term of number of symptoms after controlling for the linear number of symptom term to test for a curvilinear relationship. The quadratic term was significantly related to physical activity, OR (95% CI) = .97 (.94–.99), p < .05, as was related to disability, OR (95% CI) = 1.65 (1.41–1.93), p < .0001; non-alcohol mental disorder status, OR (95% CI) = 1.16 (1.06–1.28), p < .01; marital status, OR (95% CI) = .96 (.93–.99), p < .001; education, OR (95% CI) = 1.04 (.99–1.08), p = .07; age, OR (95% CI) = .98 (.98–.99), p < .0001; male sex, OR (95% CI) = .70 (.66–.74), p < .0001. As illustrated in Figure 1, rates of physical activity systematically increase from low to moderate symptom counts and subsequently decrease from moderate to high symptom counts. Interactions between alcohol use disorder symptoms and both age and gender in predicting physical activity were non-significant.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted percentage of individuals meeting PA recommendations by number of alcohol disorder symptoms (line represents the quadratic trend).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to focus on the relationships between alcohol use disorders and physical activity. The large, nationally representative sample and careful alcohol disorder measurement applied in NESARC made it possible to identify a significant potential source of heterogeneity in the alcohol–physical activity relationship using both DSM-IV diagnoses and symptom counts. The results suggest that alcohol abuse is associated with increased rates of physical activity in the general population, whereas dependence is not. Number of symptoms demonstrated a curvilinear relationship with physical activity such that physical activity rates were highest at moderate symptom levels.

The current results help elucidate the nebulous findings regarding the relationship between alcohol use and physical activity (2,6,17). Current results are consistent with past findings indicating a positive relationship between participation in physical activity and alcohol use (22), but suggest that this relationship may degrade when alcohol use is excessive and associated with extreme physical and psychological consequences as in the case of dependence or high symptom counts. We speculate that the functional impairment and distress associated with forms of alcohol use disorder may limit one’s ability to exercise. Several prior studies that found linear relations between alcohol use frequency and physical activity used young samples with slight variability at the severe end of alcohol use pathology and may not have been able to detect curvilinear effects caused by the degradation of this association among individuals with more severe forms of alcohol disorders.

Though the curvilinear effect was consistent with hypotheses, it should be interpreted with caution as the quadratic term in the model met only uncorrected levels of statistical significance (p < .05). It is common to find less robust effect for quadratic terms, as these analyses typically provide less power than standard linear terms (23). However, the effect of the binary alcohol abuse variable was relatively robust, which increases confidence in the pattern of findings (less severe forms of alcohol use disorder associated with higher rates of physical activity).

Exploratory analyses examining age and gender as moderators of the relation between alcohol use disorder and physical activity yielded no significant effects. While some studies have found moderation by gender and age (13), others have not (2). The current results suggest that the non-linear relation between physical activity and alcohol use pathology are not explained by variation in age and gender and add support to the notion that with severe forms of alcohol use disorder pathology any relation with physical activity degrades.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s strengths and limitations. First, the nature of the cross-sectional and retrospective design makes it susceptible to recall biases, and precludes any causal or temporal interpretations. There is evidence that self-report methods have adequate reliability and validity (19) and are therefore useful for large population-based designs such as the current study in which objective indicators may be difficult to collect. Finally, this study lacked specific data on social, environmental, and personality factors that might account for the findings; thus, any discussion of the possible mechanisms that motivate the present findings purely speculative. Thus, further research on sport-specific, demographic, biological, and socio-cultural processes that underlie the physical activity–alcohol relationship is warranted. Study strengths include that the data were from a large nationally representative sample, rigorous discounting of potential confounds using covariate adjustment enhances internal validity, and diagnostic data on alcohol use disorder were extensive. The present sample that included a wide range of ages and alcohol use pathology may have been better suited to detect potential heterogeneity in the alcohol–physical activity relationship across the continuum of alcohol use disorder than previous papers.

In sum, the current results behoove health professionals to monitor alcohol use disorders, particular alcohol abuse, and moderate–severity alcohol use pathology, among active individuals, who may otherwise appear healthy and fit. Additionally, alcohol interventions should be disseminated for overlooked groups, such as physically active individuals. Finally, these results indicate that efforts to enhance physical activity in individuals with severe forms of alcohol use disorder may benefit alcohol treatment in order to enhance the efficacy of activity interventions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elder C, Leaver-Dunn D, Wang MQ, Nagy S, Green L. Organized group activity as a protective factor against adolescent substance use. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24(2):108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 2.French MT, Popovici I, Maclean JC. Do alcohol consumers exercise more? Findings from a national survey. J Inf. 2009;24:1. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.0801104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laaksonen M, Luoto R, Helakorpi S, Uutela A. Associations between health-related behaviors: A 7-year follow-up of adults. Prev Med. 2002;34(2):162–170. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair S, Jacobs D, Jr, Powell K. Relationships between exercise or physical activity and other health behaviors. Publ Health Rep. 1985;100(2):172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buscemi J, Martens M, Yurasek AM, Smith AE. Moderators of the relationship between physical activity and alcohol consumption in college students. J Am Col Health. 2011;59(6):503–509. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.518326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smothers B, Bertolucci D. Alcohol consumption and health-promoting behavior in a US household sample: Leisure-time physical activity. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(4):467–476. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parra J, Hawley D, Arrington CN, Bell R, Nixon K, Leasure L. The Effects of Voluntary Exercise on Subsequent Alcohol Consumption. Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Last accessed on April 11, 2011]; Available at http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=452.

- 10.Musselman JRB, Rutledge PC. The incongruous alcohol–activity association: Physical activity and alcohol consumption in college students. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11(6):609–618. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piazza-Gardner AK, Barry AE. Examining physical activity levels and alcohol consumption: Are people who drink more active? Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(3):95–104. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100929-LIT-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray LA, Hutchison KE, Leventhal AM, Miranda R, Jr, Francione C, Chelminski I, Young D, Zimmerman M. Diagnosing alcohol abuse in alcohol dependent individuals: Diagnostic and clinical implications. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6–7):587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lisha NE, Martens M, Leventhal AM. Age and gender as moderators of the relationship between physical activity and alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2011;36(9):933–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Last accessed on April 11, 2011 Available at http://www. health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/summary.aspx.

- 17.Mukamal K, Ding E, Djoussé L. Alcohol consumption, physical activity, and chronic disease risk factors: A population-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Publ Health. 2006;6(1):118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yore MM, Ham SA, Ainsworth BE, Kruger J, Reis JP, KOHL HW, III, Macera CA. Reliability and validity of the instrument used in BRFSS to assess physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1267. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180618bbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan W, Huang B, Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisha NE, Sussman S. Relationship of high school and college sports participation with alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use: A review. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]