Abstract

Objective

Disordered eating occurs in women at both weight extremes of anorexia nervosa (AN) and obesity. Cortisol, peptide YY (PYY), Ieptin, and ghrelin are hormones involved in appetite and feeding behavior that vary with weight and body fat. Abnormal levels of these hormones have been reported in women with AN, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA), and obesity. The relationship between appetite-regulating hormones and disordered eating psychopathology is unknown. We therefore studied the relationship between orexigenic and anorexigenic hormones and disordered eating psychopathology in women across a range of weights.

Design

A cross-sectional study of 65 women, 18–45 years: 16 with AN, 12 normal-weight with HA, 17 overweight or obese, and 20 normal-weight in good health.

Methods

Two validated measures of disordered eating psychopathology, the Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) and Eating Disorders Inventory-2 (EDI-2), were administered. Fasting PYY, Ieptin, and ghrelin levels were measured; Cortisol levels were pooled from serum samples obtained every 20 min from 2000 to 0800 h.

Results

Cortisol and PYY levels were positively associated with disordered eating psychopathology including restraint, eating concerns, and body image disturbance, independent of body mass index (BMI). Although Ieptin levels were negatively associated with disordered eating psychopathology, these relationships were not significant after controlling for BMI. Ghrelin levels were generally not associated with EDE-Q or EDI-2 scores.

Conclusions

Higher levels of Cortisol and PYY are associated with disordered eating psychopathology independent of BMI in women across the weight spectrum, suggesting that abnormalities in appetite regulation may be associated with specific eating disorder pathologies.

Introduction

Both anorexigenic and orexigenic pathways are linked to body weight in humans. Cortisol, peptide YY (PYY), Ieptin, and ghrelin have been implicated in the regulation of appetite and feeding behavior. Levels of these hormones differ based on body weight and body fat (1–5). Women with anorexia nervosa (AN), a psychiatric disorder associated with low weight, self-induced starvation, and amenorrhea, are known to have dysregulation of appetite-mediating hormones (6–9). Overweight and obese women also have abnormal levels of appetite-regulating hormones compared with normal-weight women (1, 2, 10), and despite extreme differences in weight, may also experience abnormalities in eating behaviors and weight-related cognitions (11–13). In addition, some women with AN have a history of obesity (14) and women with bulimia may be obese (15). It is not known whether appetite-regulating hormones influence disordered eating psychopathology. Although some abnormalities in levels of appetite-regulating hormones may represent expected adaptive responses to energy imbalance, others may be paradoxical. Furthermore, several of these hormonal differences persist in those with AN despite weight recovery (7, 16). A separate line of research has demonstrated altered levels of appetite-regulating hormones and increased disordered eating pathology in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA) (17–20), suggesting that these abnormalities may exist, independent of low or high weight. Taken together, these findings raise the question of whether dysregulation of hormones involved in appetite may underlie the development or maintenance of disordered eating psychopathology. To address this question, we investigated the association of four appetite-regulating hormones – Cortisol, PYY, leptin, and ghrelin – with measures of disordered eating psychopathology in underweight women with AN, normal-weight women with HA, overweight or obese (OB) women, and normal-weight healthy women. We hypothesized that appetite-regulating hormones would be associated with disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in women across the weight spectrum, independent of body mass index (BMI), using two well-validated measures (21, 22).

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We studied 65 women aged 18–45: 16 with AN, 12 normal-weight with HA, 17 OB, and 20 normal-weight in good health (HC). All subjects were recruited from the community through advertisements and referrals from healthcare providers. Patient characteristics, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (23) scores, fasting leptin levels, and pooled 12 h overnight Cortisol levels were previously reported in AN, HA, and HC (24). Those who completed self-assessment measures of disordered eating psychopathology and an additional group of OB subjects were included in this analysis. The Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) and Eating Disorders Inventory-2 (EDI-2) scores and their relationship to hormone levels had not been previously reported in these subjects.

Subjects with AN met DSM-IV criteria, including intense fear of gaining weight, body image disturbance, weight <85% of ideal body weight (IBW) as determined by the 1983 Metropolitan Life Tables (25), and amenorrhea for at least 3 consecutive months.

HA were 90–110% of IBW with a BMI <25 kg/m2 and reported amenorrhea for at least 3 consecutive months. Exclusion criteria included polycystic ovarian syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, premature ovarian failure, and history of AN.

HC were at least 90% of IBW with a BMI <25 kg/m2 and reported regular menstrual cycles. HC reported no significant medical problems or history of amenorrhea, disordered eating, or significant anxiety or depression.

OB had a BMI of 25–40 kg/m and reported regular menstrual periods. OB reported no significant medical problems or history of amenorrhea, disordered eating, or significant anxiety or depression.

All subjects were required to have a normal TSH or free thyroxine to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included diabetes mellitus, active abuse of drugs or alcohol, use of medications known to affect Cortisol levels within 3 months (including estrogen), use of depot medroxyprogesterone within 6 months, and pregnancy or breastfeeding within 6 months of the study.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Health Care, Inc. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to any procedures. All subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center of Massachusetts General Hospital for an outpatient screening visit and an inpatient overnight visit.

At the screening visit, height, weight, and elbow breadth were measured by research bionutritionists, blood was drawn for screening laboratory tests, and a comprehensive history and physical examination were performed. Exercise patterns and alcohol intake were assessed. Percent IBW was calculated as described above. BMI was obtained by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Frame size was determined by comparing elbow breadth to race-specific norms derived from the US Health and Nutritional Examination Survey-I (25).

During the inpatient overnight visit, % IBW and BMI were reevaluated. Body composition was assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic 4500, Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). This technique has a precision of 3% for fat mass (26). Nutritional intake was assessed by the 24 h diet recall. Medical history and physical examination were performed. The EDE-Q and the EDI-2 were self-administered. Study staff administered the HAM-D (23). An i.v. catheter was placed and subjects were allowed to acclimate to their rooms for at least 2 h, followed by frequent sampling of blood every 20 min from 2000 to 0800 h. Blood draws were performed by experienced research nurses at the Clinical Research Center with identical procedures between patients and controls. Subjects were asked to fast starting at 2000 h, and were allowed to sleep through the night. Fasting leptin, ghrelin, and PYY levels were obtained at 0745 h. Overnight serum samples were pooled for average Cortisol levels. HC and OB presented for their overnight visits during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

Psychological measures

The EDE-Q is a well-validated 36-item self-report measure assessing the severity of characteristic eating disorder psychopathology in four categories: dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern. A global score can be calculated. Behaviors such as binge eating, purging, and other compensatory activities such as excessive exercise are also evaluated (27). Normative data (mean±s.d.) based on two studies of adult women (28, 29) are as follows: dietary restraint, 1.3 ± 1.4 (28), 1.62 ± 1.54 (29); eating concern, 0.76±1.06, 1.11 ± 1.11; weight concern, 1.79 ± 1.51, 1.97 ± 1.56; shape concern, 2.23 ± 1.65, 2.27 ± 1.54; and global concern, 1.52 ± 1.25, 1.74 ± 1.30.

The EDI-2 is a well-validated self-report measure with subscale scores assessing core eating disorder psycho-pathology (drive for thinness, bulimia, and body dissatisfaction) and related psychological features (ineffectiveness, perfectionism, interpersonal distrust, interoceptive awareness, maturity fears, asceticism, impulse regulation, and social insecurity) (22). Normative data (mean±s.e.m. of measurement) are based on the EDI Manual norms (22), which were determined using a sample of female college students, and are as follows: drive for thinness, 5.5 ± 2.2; bulimia, 1.2 ± 0.9; body dissatisfaction, 12.2 ± 3.0; ineffectiveness, 2.3 ± 1.6; perfectionism, 6.2 ± 2.5, interpersonal distrust, 2.0 ± 1.3; interoceptive awareness, 3.0 ± 2.1; maturity fears, 2.7 ± 1.3; asceticism, 3.4 ± 1.6; impulse regulation, 2.3 ± 1.6; and social insecurity, 3.3 ±1.5.

The HAM-D is a 17-item semi-structured interview that is widely used to measure depressive symptoms in clinical trials and has excellent internal consistency (23). On all of the psychological measures, higher scores indicate increased symptomatology.

Biochemical analysis

Serum and plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Serum Cortisol was measured by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Architect System, Abbot Diagnostics). The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) ranged from 2.1 to 4.8% and the total CV values ranged from 3.9 to 7.7% The sensitivity was 0.8 µg/dl. Serum leptin levels were measured using an RIA kit from Linco Research, a division of Millipore Inc. (St Charles, MO, USA). The intra-assay CV ranged from 3.4 to 8.3% and the inter-assay CV ranged from 3.6 to 6.3%. The sensitivity was 0.5 ng/ml. Plasma ghrelin levels were measured using an RIA kit from Linco Research, a division of Millipore Inc. The intra-assay CV ranged from 10.0 to 14.4% and the inter-assay CV ranged from 14.7 to 16.7%. The sensitivity was 93 pg/ml. Serum total PYY levels were measured using an RIA kit from Linco Research, a division of Millipore Inc. The intra-assay CV ranged from 1.5 to 2.7% and the inter-assay CV ranged from 6.1 to 6.9%. The sensitivity was 1.4 pg/ml.

Data analysis

JMP Statistical Discoveries (version 5.01; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Clinical characteristics, hormone levels, and measures of disordered eating attitudes and behavior were compared using overall ANOVA; variables that were significantly different were then compared by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Multiple comparisons were controlled using the Tukey–Kramer method. Linear regression analyses were used to investigate the associations between hormone levels and measures of disordered eating psychopathology. Multivariate least-square analyses were constructed to control for BMI and other potential confounders. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value <0.05. Data are reported as mean±s.e.m.

Results

Subject characteristics

Subject characteristics are presented in Table 1. The groups did not differ in age. As per study design, BMI, % IBW, and % fat were lowest in AN, intermediate in HA and HC, and highest in OB. There were no differences between the groups in reported 24 h calorie intake, total fat, carbohydrate, or protein content. Age of menarche did not differ between the groups. By definition, HC and OB had no history of amenorrhea. The total months of amenorrhea was not significantly different in AN compared to HA. Mean level of exercise was higher in AN compared with OB and HC.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and hormone levels.

|

P values |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN (n = 16) |

HA (n = 12) |

OB (n = 17) |

HC (n = 20) |

AN vs HA | AN vs OB | AN vs HC | HA vs OB | HA vs HC | OB vs HC | Overall ANOVA |

|

| Age (years) | 25.9 ± 1.5 | 27.3 ± 1.8 | 29.5 ± 2.0 | 27.2 ± 1.6 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.2 ± 0.3 | 20.9 ± 0.4 | 31.3 ± 1.0 | 22.3 ± 0.3 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.01 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001 |

| % Ideal body weight | 79.2 ± 1.4 | 92.9 ± 1.4 | 132.3 ± 4.3 | 98.0 ± 1.4 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.03 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001 |

| % Fat | 17.6 ± 0.9 | 23.6 ± 0.8 | 37.1 ± 1.2 | 27.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.03 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001 |

| Caloric intake (kcal) | 1808 ± 149 | 1664 ± 87 | 1713 ± 176 | 1679 ± 132 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Age of menarche | 13.1 ± 0.3 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.4 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Months amenorrhea | 62.9 ± 16.4 | 34.9 ± 9.6 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | < 0.0001 | NS | < 0.0001 |

| Hours exercise/week | 8.1 ± 1.5 | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | NS | 0.001* | 0.009* | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.0004 |

| Number of alcoholic drinks/week | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 12 h pooled Cortisol (µg/dl) | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 0.09 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.001* | 0.05 | 0.02 | < 0.0001 |

| PYY (pg/ml) | 96.6 ± 6.8 | 75.3 ± 4.6 | 66.4 ± 2.7 | 78.0 ± 6.0 | 0.02 | 0.0002* | 0.05 | 0.09 | NS | NS | 0.002 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 23.6 ± 2.9 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 0.0006 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001* | 0.03 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001 |

| Ghrelin (pg/ml) | 1121 ± 100 | 1004 ± 88 | 543 ± 47 | 1049 ± 108 | NS | < 0.0001* | NS | < 0.0001* | NS | 0.0002* | < 0.0001 |

Overall ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test, means±s.e.m.

P<0.05 after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Tukey–Kramer method. NS, not significant.

Hormone levels

Hormone levels are presented in Table 1. Mean Cortisol levels were elevated in AN compared with OB and HC. Mean fasting PYY levels were highest in AN, and were associated with overnight Cortisol levels (r=0.3 7, P= 0.003). This relationship was no longer statistically significant after controlling for BMI (P=0.07). Mean leptin levels were higher and mean ghrelin levels were lower in OB than all other groups.

Measures of disordered eating attitudes and behavior

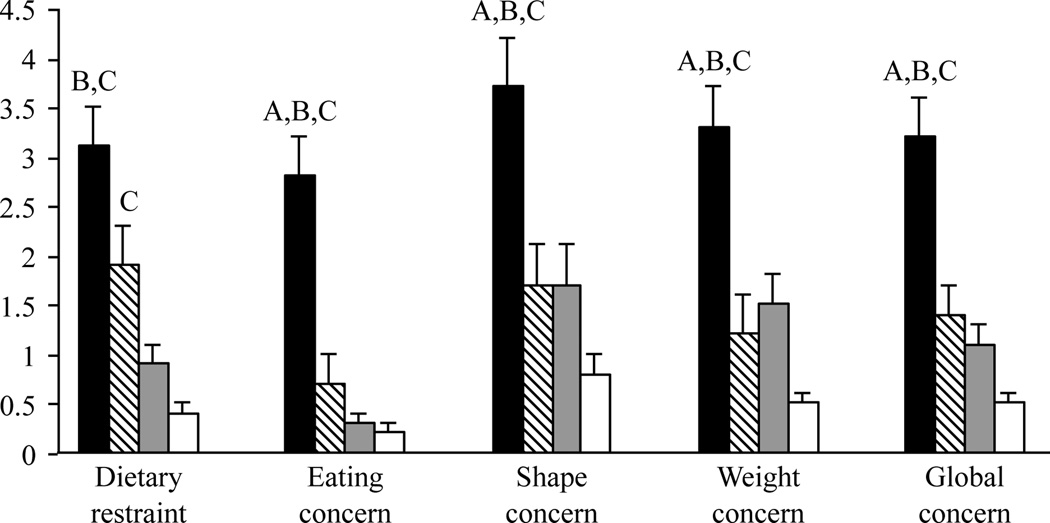

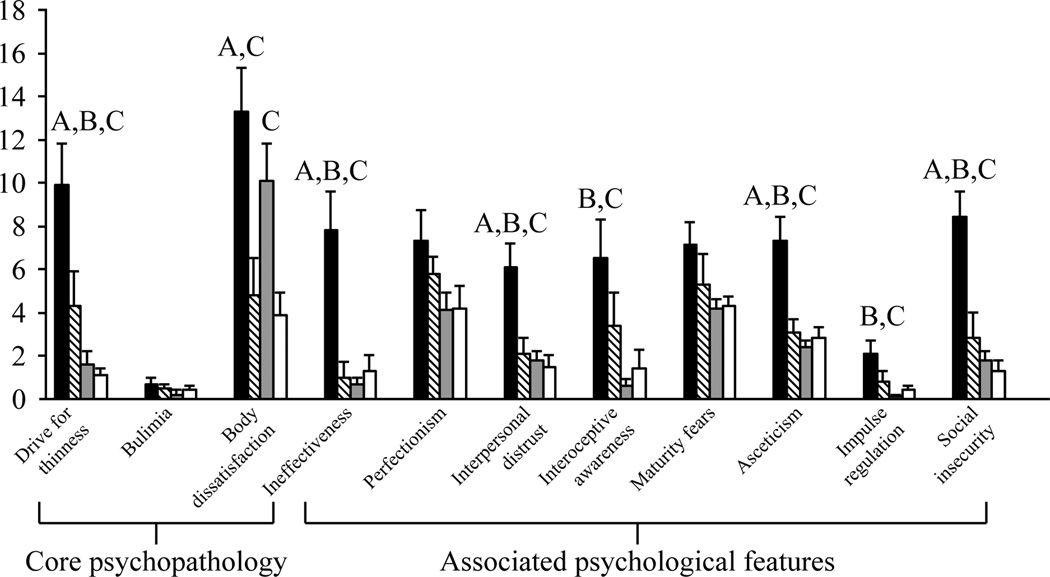

The EDE-Q and EDI-2 scores are presented in Table 2 and Figs 1 and 2. As expected, the AN group demonstrated increased eating disorder psychopathology relative to the other groups indexed by EDE-Q dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern scores, and EDI-2 drive for thinness scores. In contrast, EDE-Q scores and EDI-2 core eating disorder pathology scores were within the normal ranges for women in the other three groups. Notably, however, there was a relative increase in the EDE-Q dietary restraint scores in HA, and in EDI-2 body dissatisfaction in OB. Associated eating disorder behaviors measured by the EDE-Q, including binging and purging, were normal in all groups. Global EDE-Q scores were lowest in HC, intermediate in OB and HA, and highest in AN.

Table 2.

Measures of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

|

P values |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN | HA | OB | HC | AN vs HA | AN vs OB | AN vs HC | HA vs OB | HA vs HC | OB vs HC | Overall ANOVA |

|

| EDE-Q | |||||||||||

| Core psychopathology | |||||||||||

| Dietary restraint | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.0001* | <0.0001* | 0.04 | 0.0004* | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

| Eating concern | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.0008* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | 0.05 | 0.009 | NS | <0.0001 |

| Shape concern | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.005* | 0.002* | <0.0001* | NS | 0.02 | 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Weight concern | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.004* | 0.002* | <0.0001* | NS | 0.03 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 |

| Global concern | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.004* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | NS | 0.002 | 0.01 | <0.0001 |

| Associated behaviors | |||||||||||

| Objective binges/month | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.05 | NS | NS |

| Subjective binges/month | 5.1 ± 2.3 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | NS | 0.02* | 0.03* | NS | NS | 0.09 | 0.008 |

| Compensatory exercise/month | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | NS | 0.07 | 0.02* | NS | 0.03 | NS | 0.03 |

| Vomiting/month | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Laxative use/month | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Diuretic use/month | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| EDI-2 | |||||||||||

| Core psychopathology | |||||||||||

| Drive for thinness | 9.9 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 1.6 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.05* | 0.0002* | < 0.0001* | 0.08 | 0.02 | NS | < 0.0001 |

| Bulimia | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Body dissatisfaction | 13.3 ± 2.0 | 4.8 ± 1.7 | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 0.005* | NS | 0.0001* | 0.05 | NS | 0.004* | 0.0002 |

| Associated psychological features | |||||||||||

| Ineffectiveness | 7.8 ± 1.8 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.004* | 0.0002* | 0.0008* | NS | NS | NS | < 0.0001 |

| Perfectionism | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Interpersonal distrust | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 0.01* | 0.0006* | 0.0003* | NS | NS | NS | < 0.0001 |

| Interoceptive awareness | 6.5 ± 1.8 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | NS | 0.003* | 0.01* | 0.04 | NS | NS | 0.004 |

| Maturity fears | 7.1 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | NS | 0.02 | 0.02 | NS | NS | NS | 0.05 |

| Asceticism | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 0.005* | < 0.0001* | 0.0003* | NS | NS | NS | < 0.0001 |

| Impulse regulation | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | NS | 0.003* | 0.02* | 0.09 | NS | NS | 0.004 |

| Social insecurity | 8.4 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.004* | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | NS | NS | NS | < 0.0001 |

Overall ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test, means± s.e.m.

P<0.05 after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Tukey–Kramer method. NS, not significant.

Figure 1.

EDE-Q results. AN (black) scored higher on the EDE-Q than HA (diagonal lines), OB (gray), and HC (white). A, P<0.0005 vs HA; B, P<0.002 vs OB; C, P<0.0001 vs HC. Overall ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test, means±s.e.m.

Figure 2.

EDI-2 results. AN (black) scored higher than the other groups (HA, diagonal lines; OB, gray; HC, white) on most subscales. A, P<0.05 vs HA; B, P<0.004 vs OB; C, P<0.02 vs HC. Overall ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test, means±s.e.m.

With regard to the associated psychological features measured by the EDI-2, women with AN generally reported the highest scores while the scores for the other groups were within the normal range.

Relationship between hormone levels and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors

The relationships between hormone levels and measures of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors are presented in Table 3. In terms of core disordered eating psychopathology, 12 h overnight average Cortisol levels were positively associated with all EDE-Q scores and drive for thinness on the EDI-2. The relationships between overnight Cortisol levels and all EDE-Q scales were independent of BMI and PYY levels. In addition, the associations between overnight Cortisol levels and EDE-Q scores on dietary restraint and eating concern remained significant after controlling for depressive symptoms, as assessed by the HAM-D. PYY levels were also associated with core eating disorder pathology measured by the EDE-Q and EDI-2; positive associations with EDE-Q eating concern and EDI-2 drive for thinness were independent of BMI. The relationship between PYY and EDI-2 drive for thinness remained significant after controlling for Cortisol levels. The relationships between the hormones Cortisol and PYY and core eating disorder psychopathology as assessed by the EDE-Q and EDI-2 that were independent of BMI were still present if the overweight subjects (n = 7) were excluded from the analysis. While leptin levels were inversely associated with level of eating concern scores on the EDE-Q, this relationship was not significant after controlling for BMI. Ghrelin levels were not associated with measures of core eating disorder pathology.

Table 3.

Correlations between the hormone levels and measures of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

| Cortisol | PYY | Leptin | Ghrelin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q | ||||

| Core psychopathology | ||||

| Dietary restraint | 0.53‡,§ | 0.22* | −0.17 | 0.04 |

| Eating concern | 0.56‡,§ | 0.41‡,§ | −0.36‡ | 0.09 |

| Shape concern | 0.47‡,§ | 0.26† | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| Weight concern | 0.43‡,§ | 0.26† | −0.09 | 0.00 |

| Global concern | 0.53‡,§ | 0.30† | −0.17 | 0.03 |

| Associated behaviors | ||||

| Overexercise/month | 0.29‡,§ | 0.26† | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| EDI-2 | ||||

| Core psychopathology | ||||

| Drive for thinness | 0.27† | 0.35‡,§ | −0.22* | 0.04 |

| Bulimia | 0.08 | 0.22* | −0.20 | 0.00 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.19§ | 0.13 | 0.15 | −0.08 |

| Associated psychological features | ||||

| Ineffectiveness | 0.36‡ | 0.27† | −0.29† | 0.10 |

| Perfectionism | 0.10 | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.01 |

| Interpersonal distrust | 0.36‡,§ | 0.26† | −0.27† | 0.07 |

| Interoceptive awareness | 0.29† | 0.17 | −0.28† | 0.14 |

| Maturity fears | 0.19 | 0.09 | −0.24* | 0.27† |

| Asceticism | 0.32† | 0.35‡ | −0.30† | 0.09 |

| Impulse regulation | 0.27† | 0.33‡,§ | −0.21 | 0.16 |

| Social insecurity | 0.30† | 0.40‡,§ | −0.24* | 0.21 |

Linear regression, multivariate least-square analyses

P<0.10

P≤0.05,

P≤0.01,

P≤0.05 after controlling for BMI.

With regard to the relationship between the hormone levels and the disordered eating-related psychological features measured by the EDI-2, both Cortisol and PYY were positively associated with several of the scale scores, while leptin levels were negatively associated with these features. After controlling for BMI and PYY, positive relationships between Cortisol and interpersonal distrust remained. In addition, associations between PYY and impulse regulation and social insecurity were independent of BMI and Cortisol levels. Correlations between leptin levels and these features were nonsignificant after controlling for BMI. Ghrelin levels were associated with the scores on the maturity fears subscale of the EDI-2. However, this association was no longer significant after controlling for BMI.

Discussion

In this study of underweight amenorrheic women with AN, normal-weight women with HA, OB women, and normal-weight healthy women, overnight serum Cortisol and fasting PYY levels were associated with disordered eating psychopathology, independent of BMI.

Levels of hormones involved in appetite and feeding behavior, including Cortisol, PYY, leptin, and ghrelin, differ based on body weight and fat (1–5), and abnormal levels of these hormones have been reported in women with AN (7–9, 30) and in functional HA (17, 19, 20, 31), a disorder commonly associated with subclinical disordered eating (18–20). It is unknown whether appetite-regulating hormone abnormalities contribute to disordered eating symptomatology. We hypothesized that these hormones would be associated with severity of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors regardless of body weight.

Cortisol, a key component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, is released in response to psychological or physical ‘stress’ and may stimulate appetite (3). AN and HA are both associated with elevated levels of endogenous Cortisol, which is presumably stress related (9,17, 32–34). An alternative possibility is that hypercortisolemia is an adaptive response to increase and mobilize energy stores in the face of decreased weight or body fat and/or increased demand. Exposure to high levels of Cortisol, for example, in Cushing’s syndrome or exogenous corticosteroid administration, stimulates appetite and weight gain with central fat accumulation when there is sufficient substrate. For example, when patients with AN gain weight, preferential truncal fat gain is seen (35). In contrast, characteristic symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are anorexia and weight loss. Other studies have reported an association between measures of Cortisol and dietary restraint in pre- and post-menopausal women (36–38). We have shown that in comparison to healthy controls, average overnight Cortisol levels were higher in women with HA and AN (24). In this study, across groups of women of differing weights, pooled overnight serum Cortisol levels were positively associated with disordered eating attitudes and behaviors as assessed by the EDE-Q and EDI-2, independent of BMI. Furthermore, the relationships between overnight Cortisol levels and dietary restraint and eating concern measures of EDE-Q core disordered eating psychophathology were independent of depressive symptoms. Therefore, hypercortisolemia may be an adaptive mechanism to starvation, which further exacerbates an underlying pattern of disordered eating.

PYY is an anorexigenic polypeptide hormone secreted by the intestine in response to food intake (39). In the hypothalamus, PYY modulates appetite by binding to Y2 receptors in the arcuate nucleus, promoting anorexigenic in favor of orexigenic pathways (40). PYY levels are elevated in AN (7, 41) and HA (31), and low in obesity (1), and are inversely associated with BMI (1). In a 2003 study of 12 obese and 12 lean subjects, Batterham et al. (1) reported that infusion of PYY resulted in a similar reduction of appetite and caloric intake in each group. A study of exercising women with HA and exercising and sedentary healthy controls found that PYY levels were associated with drive for thinness as assessed by the EDI-2 (31). We demonstrated that PYY levels are correlated with characteristics of disordered eating as well as associated features, and that some of these relationships, including core disordered eating psychopathology measures of EDE-Q eating concern and EDI-2 drive for thinness, remained significant after controlling for BMI. Although abnormal PYY levels may be secondary to disordered eating thinking and behavior, low levels of PYY in obesity and high levels in AN despite PYY’s function in signaling satiety argue for a possible etiologic role.

There is some evidence suggesting that PYY may be involved in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis signaling. Administration of i.v. PYY to dogs stimulates secretion of ACTH and Cortisol (42, 43). Consistent with these data, we found a strong positive correlation between morning fasting PYY levels and mean overnight Cortisol levels. PYY and Cortisol were independently associated with different features of disordered eating as measured by the EDE-Q and EDI-2, suggesting specific effects of these hormones on disordered eating pathology.

Leptin, an anorexigenic hormone secreted by adipocytes, correlates with BMI and fat mass (5, 10). Levels are low in AN (8, 44) and HA (19, 45), and high in obesity (10). After long-term recovery from AN, leptin levels normalize (46). A recent study demonstrated an inverse association between leptin levels and drive for thinness on the EDI-2 in women with AN, but not in healthy controls (47). Monteleone et al. (5) found no relationship between leptin levels and EDI scores in 21 women with AN, 32 with bulimia nervosa, 14 with binge eating disorder, and 25 controls. In contrast, Ehrlich et al. (47) showed a negative correlation between leptin and drive for thinness on the EDI-2 when controlling for BMI in 57 women with AN, but not in controls. In our study, leptin was inversely associated with scores on the eating concern subscale of the EDE-Q and with several associated psychological features measured by the EDI-2 in the entire sample. However, these relationships were no longer significant after controlling for BMI. This may reflect leptin’s role as a marker for fat, where women with the lowest body fat (AN) have increased eating disorder pathology, rather than as a mediator of disordered eating thought and behavior.

Ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone secreted by the stomach, is elevated in AN (7, 30) and HA (20, 31), low in obesity (2), and inversely related to BMI (2). Schneider et al. (48) reported an association between ghrelin levels and elevated scores on the Eating Attitude Test, a measure of abnormal eating thinking and behavior, in normal-weight women with HA. A correlation between ghrelin and drive for thinness subscale of the EDI-2 has been reported in a study of exercising women with HA and controls (31). Consistent with a previous report (46), we found that ghrelin was associated only with the maturity fears subscale of the EDI-2; however, this relationship was no longer significant after controlling for BMI.

This study has several limitations. First, sample sizes across groups were small, which may have limited power to detect differences. Owing to the cross-sectional study design, causality cannot be determined. In addition, we measured total but not acylated ghrelin levels. Acylated ghrelin is considered the most active form of ghrelin, but due to rapid degradation requires special collection techniques with a preservative for accurate assessment (49). It is possible that had we measured the active form of ghrelin, we would have identified associations with disordered eating psychopathology. Furthermore, the EDE-Q and EDI-2 are excellent measures of disordered eating psychopathology in AN. Additional instruments may have been useful to tap into subclinical disordered eating psychopathology in HA and OB. For example, nuanced measures that more carefully assess the nature of exercise (e.g. motivation, compulsivity, and intensity) may be useful in HA, or those that assess the psychopathology of binge eating disorder (e.g. measures of emotional eating) may be useful for individuals with overweight and obesity.

In summary, we found a strong association between overnight Cortisol and fasting morning PYY levels and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, independent of BMI. These findings suggest that these appetite-regulating hormones may be factors in disordered eating symptomatology. Further research on the role of appetite-regulating hormones in the development of disordered eating will be important.

Acknowledgements

We thank the nurses and bionutritionists at the Massachusetts General Hospital Clinical Research Center and the subjects who participated in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the investigator-initiated grant from Bioenvision; NIH: M01 RR01066, UL1 RR025758, and P30-DK040561; The Clinical Investigator Training Program: Harvard/ MIT Health Sciences and Technology – Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in collaboration with Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Co.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- 1.Batterham RL, Cohen MA, Ellis SM, Le Roux CW, Withers DJ, Frost GS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3-36. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:941–948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiiya T, Nakazato M, Mizuta M, Date Y, Mondal MS, Tanaka M, Nozoe S-I, Hosoda H, Kangawa K, Matsukura S. Plasma ghrelin levels in lean and obese humans and the effect of glucose on ghrelin secretion. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87:240–244. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieuwenhuizen AG, Rutters F. The hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal-axis in the regulation of energy balance. Physiology and Behavior. 2008;94:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutters F, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Lemmens SG, Born JM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Hypothalamus/pituitary/adrenal (HPA) axis functioning in relation to body fat distribution. Clinical Endocrinology. 2010;72:738–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monteleone P, Di Lieto A, Tortorella A, Longobardi N, Maj M. Circulating leptin in patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder: relationship to body weight, eating patterns, psychopathology and endocrine changes. Psychiatry Research. 2000;94:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawson EA, Klibanski A. Endocrine abnormalities in anorexia nervosa. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;4:407–414. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakahara T, Kojima S, Tanaka M, Yasuhara D, Harada T, Sagiyama K, Muranaga T, Nagai N, Nakazato M, Nozoe S, Naruo T, Inui A. Incomplete restoration of the secretion of ghrelin and PYY compared to insulin after food ingestion following weight gain in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grinspoon S, Gulick T, Askari H, Landt M, Lee K, Anderson E, Ma Z, Vignati L, Bowsher R, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Serum leptin levels in women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:3861–3863. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misra M, Miller KK, Almazan C, Ramaswamy K, Lapcharoensap W, Worley M, Neubauer G, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Alterations in Cortisol secretory dynamics in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and effects on bone metabolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89:4972–4980. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jequier E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;967:379–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packianathan IC, Sheikh M, Feben S, Finer N. The Eating Disorder Inventory in a OK National Health Service Obesity Clinic and its response to modest weight loss. Eating Behaviors. 2002;3:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones M, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Psychological and behavioral correlates of excess weight: misperception of obese status among persons with Class II obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:628–632. doi: 10.1002/eat.20746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green GC, Buckroyd J. Disordered eating cognitions and behaviours among slimming organization competition winners. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2008;21:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garfinkel PE, Moldofsky H, Garner DM. The heterogeneity of anorexia nervosa. Bulimia as a distinct subgroup. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:1036–1040. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220074008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JE, Pyle RL, Eckert ED, Hatsukami D, Soll E. Bulimia nervosa in overweight individuals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990;178:324–327. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfluger PTKJ, Castaneda TR, Vahl T, D’Alessio DA, Kruthaupt T, Benoit SC, Cuntz U, Rochlitz HJ, Moehlig M, Pfeiffer AF, Koebnick C, Weickert MO, Otto B, Spranger J, Tschöp MH. Effect of human body weight changes on circulating levels of peptide YY and peptide YY3-36. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:583–588. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biller BM, Federoff HJ, Koenig JI, Klibanski A. Abnormal Cortisol secretion and responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1990;70:311–317. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-2-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bomba M, Gambera A, Bonini L, Peroni M, Neri F, Scagliola P, Nacinovich R. Endocrine profiles and neuropsychologic correlates of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea in adolescents. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;87:876–885. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren MP, Voussoughian F, Geer EB, Hyle EP, Adberg CL, Ramos RH. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: hypoleptinemia and disordered eating. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84:873–877. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.3.5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider LF, Warren MP. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is associated with elevated ghrelin and disordered eating. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garner D. Eating Disorders lnventory-2: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawson EA, Donoho D, Miller KK, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Lydecker J, Wexler T, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Hypercortisolemia is associated with severity of bone loss and depression in hypothalamic amenorrhea and anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94:4710–4716. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisancho AR, Flegel PN. Elbow breadth as a measure of frame size for US males and females. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1983;37:311–314. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazess RB, Barden HS, Bisek JP, Hanson J. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for total-body and regional bone-mineral and soft-tissue composition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;51:1106–1112. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorders examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. 12th edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for young adult women. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luce KH, Crowther JH, Pole M. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:273–276. doi: 10.1002/eat.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misra M, Miller KK, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Secretory dynamics of ghrelin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa, healthy adolescents American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;289:E347–E356. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00615.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheid JL, Williams NI, West SL, VanHeest JL, De Souza MJ. Elevated PYY is associated with energy deficiency and indices of subclinical disordered eating in exercising women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. Appetite. 2009;52:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Licinio J, Wong ML, Gold PW. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research. 1996;62:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh BY, Liu JH, Berga SL, Quigley ME, Laughlin GA, Yen SS. Hypercortisolism in patients with functional hypothalamic-amenorrhea. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1988;66:733–739. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-4-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berga SL, Daniels TL, Giles DE. Women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea but not other forms of anovulation display amplified Cortisol concentrations. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;67:1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grinspoon S, Thomas L, Miller K, Pitts S, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Changes in regional fat redistribution and the effects of estrogen during spontaneous weight gain in women with anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;73:865–869. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean JA, Barr SI, Prior JC. Cognitive dietary restraint is associated with higher urinary Cortisol excretion in healthy premenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;73:7–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson DA, Shapiro JR, Lundgren JD, Spataro LE, Frye CA. Self-reported dietary restraint is associated with elevated levels of salivary Cortisol. Appetite. 2002;38:13–17. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rideout CA, Linden W, Barr SI. High cognitive dietary restraint is associated with increased Cortisol excretion in postmenopausal women. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61:628–633. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adrian TE, Ferri GL, Bacarese-Hamilton AJ, Fuessl HS, Polak JM, Bloom SR. Human distribution and release of a putative new gut hormone, peptide YY. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renshaw D, Batterham RL. Peptide YY: a potential therapy for obesity. Current Drug Targets. 2005;6:171–179. doi: 10.2174/1389450053174523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, Gallagher K, Lin A, Lee N, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Elevated peptide YY levels in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91:1027–1033. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inui A, Inoue T, Sakatani N, Oya M, Morioka H, Mizuno N, Baba S. Biological actions of peptide YY: effects on endocrine pancreas, pituitary-adrenal axis, and plasma catecholamine concentrations in the dog. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 1987;19:353–357. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1011822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue T, Inui A, Okita M, Sakatani N, Oya M, Morioka H, Mizuno N, Oimomi M, Baba S. Effect of neuropeptide Y on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the dog. Life Sciences. 1989;44:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra M, Miller KK, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Secretory dynamics of leptin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa, healthy adolescents. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;289:E373–E381. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00041.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller KK, Parulekar MS, Schoenfeld E, Anderson E, Hubbard J, Klibanski A, Grinspoon SK. Decreased leptin levels in normal weight women with hypothalamic amenorrhea: the effects of body composition and nutritional intake. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1998;83:2309–2312. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gendall KA, Kaye WH, Altemus M, McConaha CW, La Via MC. Leptin, neuropeptide Y, and peptide YY in long-term recovered eating disorder patients. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:292–299. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrlich S, Burghardt R, Schneider N, Hein J, Weiss D, Pfeiffer E, Lehmkuhl U, Salbach-Andrae H. Leptin and its associations with measures of psychopathology in patients with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2009;116:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider LF, Monaco SE, Warren MP. Elevated ghrelin level in women of normal weight with amenorrhea is related to disordered eating. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;90:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hosoda H, Doi K, Nagaya N, Okumura H, Nakagawa E, Enomoto M, Ono F, Kangawa K. Optimum collection and storage conditions for ghrelin measurements: octanoyl modification of ghrelin is rapidly hydrolyzed to desacyl ghrelin in blood samples. Clinical Chemistry. 2004;50:1077–1080. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]